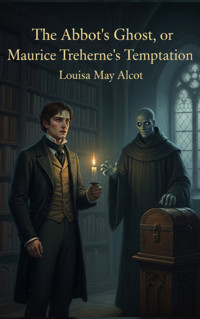

The Mysterious Key and What It Opened

The Mysterious Key and What It OpenedChapter IChapter IIChapter IIIChapter IVChapter VChapter VIChapter VIIChapter VIIICopyright

The Mysterious Key and What It Opened

Louisa May Alcott

Chapter I

THE PROPHECYTrevlyn lands and Trevlyn gold,Heir nor heiress e'er shall hold,Undisturbed, till, spite of rust,Truth is found in Trevlyn dust."This is the third time I've found you poring over that old

rhyme. What is the charm, Richard? Not its poetry I fancy." And the

young wife laid a slender hand on the yellow, time-worn page where,

in Old English text, appeared the lines she laughed

at.Richard Trevlyn looked up with a smile and threw by the book,

as if annoyed at being discovered reading it. Drawing his wife's

hand through his own, he led her back to her couch, folded the soft

shawls about her, and, sitting in a low chair beside her, said in a

cheerful tone, though his eyes betrayed some hidden care, "My love,

that book is a history of our family for centuries, and that old

prophecy has never yet been fulfilled, except the 'heir and

heiress' line. I am the last Trevlyn, and as the time draws near

when my child shall be born, I naturally think of his future, and

hope he will enjoy his heritage in peace.""God grant it!" softly echoed Lady Trevlyn, adding, with a

look askance at the old book, "I read that history once, and

fancied it must be a romance, such dreadful things are recorded in

it. Is it all true, Richard?""Yes, dear. I wish it was not. Ours has been a wild, unhappy

race till the last generation or two. The stormy nature came in

with old Sir Ralph, the fierce Norman knight, who killed his only

son in a fit of wrath, by a blow with his steel gauntlet, because

the boy's strong will would not yield to his.""Yes, I remember, and his daughter Clotilde held the castle

during a siege, and married her cousin, Count Hugo. 'Tis a warlike

race, and I like it in spite of the mad deeds.""Married her cousin! That has been the bane of our family in

times past. Being too proud to mate elsewhere, we have kept to

ourselves till idiots and lunatics began to appear. My father was

the first who broke the law among us, and I followed his example:

choosing the freshest, sturdiest flower I could find to transplant

into our exhausted soil.""I hope it will do you honor by blossoming bravely. I never

forget that you took me from a very humble home, and have made me

the happiest wife in England.""And I never forget that you, a girl of eighteen, consented

to leave your hills and come to cheer the long-deserted house of an

old man like me," returned her husband fondly."Nay, don't call yourself old, Richard; you are only

forty-five, the boldest, handsomest man in Warwickshire. But lately

you look worried; what is it? Tell me, and let me advise or comfort

you.""It is nothing, Alice, except my natural anxiety for

you—Well, Kingston, what do you want?"Trevlyn's tender tones grew sharp as he addressed the

entering servant, and the smile on his lips vanished, leaving them

dry and white as he glanced at the card he handed him. An instant

he stood staring at it, then asked, "Is the man here?""In the library, sir.""I'll come."Flinging the card into the fire, he watched it turn to ashes

before he spoke, with averted eyes: "Only some annoying business,

love; I shall soon be with you again. Lie and rest till I

come."With a hasty caress he left her, but as he passed a mirror,

his wife saw an expression of intense excitement in his face. She

said nothing, and lay motionless for several minutes evidently

struggling with some strong impulse."He is ill and anxious, but hides it from me; I have a right

to know, and he'll forgive me when I prove that it does no

harm."As she spoke to herself she rose, glided noiselessly through

the hall, entered a small closet built in the thickness of the

wall, and, bending to the keyhole of a narrow door, listened with a

half-smile on her lips at the trespass she was committing. A murmur

of voices met her ear. Her husband spoke oftenest, and suddenly

some word of his dashed the smile from her face as if with a blow.

She started, shrank, and shivered, bending lower with set teeth,

white cheeks, and panic-stricken heart. Paler and paler grew her

lips, wilder and wilder her eyes, fainter and fainter her breath,

till, with a long sigh, a vain effort to save herself, she sank

prone upon the threshold of the door, as if struck down by

death."Mercy on us, my lady, are you ill?" cried Hester, the maid,

as her mistress glided into the room looking like a ghost, half an

hour later."I am faint and cold. Help me to my bed, but do not disturb

Sir Richard."A shiver crept over her as she spoke, and, casting a wild,

woeful look about her, she laid her head upon the pillow like one

who never cared to lift it up again. Hester, a sharp-eyed,

middle-aged woman, watched the pale creature for a moment, then

left the room muttering, "Something is wrong, and Sir Richard must

know it. That black-bearded man came for no good, I'll

warrant."At the door of the library she paused. No sound of voices

came from within; a stifled groan was all she heard; and without

waiting to knock she went in, fearing she knew not what. Sir

Richard sat at his writing table pen in hand, but his face was

hidden on his arm, and his whole attitude betrayed the presence of

some overwhelming despair."Please, sir, my lady is ill. Shall I send for

anyone?"No answer. Hester repeated her words, but Sir Richard never

stirred. Much alarmed, the woman raised his head, saw that he was

unconscious, and rang for help. But Richard Trevlyn was past help,

though he lingered for some hours. He spoke but once, murmuring

faintly, "Will Alice come to say good-bye?""Bring her if she can come," said the physician.Hester went, found her mistress lying as she left her, like a

figure carved in stone. When she gave the message, Lady Trevlyn

answered sternly, "Tell him I will not come," and turned her face

to the wall, with an expression which daunted the woman too much

for another word.Hester whispered the hard answer to the physician, fearing to

utter it aloud, but Sir Richard heard it, and died with a

despairing prayer for pardon on his lips.When day dawned Sir Richard lay in his shroud and his little

daughter in her cradle, the one unwept, the other unwelcomed by the

wife and mother, who, twelve hours before, had called herself the

happiest woman in England. They thought her dying, and at her own

command gave her the sealed letter bearing her address which her

husband left behind him. She read it, laid it in her bosom, and,

waking from the trance which seemed to have so strongly chilled and

changed her, besought those about her with passionate earnestness

to save her life.For two days she hovered on the brink of the grave, and

nothing but the indomitable will to live saved her, the doctors

said. On the third day she rallied wonderfully, and some purpose

seemed to gift her with unnatural strength. Evening came, and the

house was very still, for all the sad bustle of preparation for Sir

Richard's funeral was over, and he lay for the last night under his

own roof. Hester sat in the darkened chamber of her mistress, and

no sound broke the hush but the low lullaby the nurse was singing

to the fatherless baby in the adjoining room. Lady Trevlyn seemed

to sleep, but suddenly put back the curtain, saying abruptly,

"Where does he lie?""In the state chamber, my lady," replied Hester, anxiously

watching the feverish glitter of her mistress's eye, the flush on

her cheek, and the unnatural calmness of her manner."Help me to go there; I must see him.""It would be your death, my lady. I beseech you, don't think

of it," began the woman; but Lady Trevlyn seemed not to hear her,

and something in the stern pallor of her face awed the woman into

submission.Wrapping the slight form of her mistress in a warm cloak,

Hester half-led, half-carried her to the state room, and left her

on the threshold."I must go in alone; fear nothing, but wait for me here," she

said, and closed the door behind her.Five minutes had not elapsed when she reappeared with no sign

of grief on her rigid face."Take me to my bed and bring my jewel box," she said, with a

shuddering sigh, as the faithful servant received her with an

exclamation of thankfulness.When her orders had been obeyed, she drew from her bosom the

portrait of Sir Richard which she always wore, and, removing the

ivory oval from the gold case, she locked the former in a tiny

drawer of the casket, replaced the empty locket in her breast, and

bade Hester give the jewels to Watson, her lawyer, who would see

them put in a safe place till the child was grown."Dear heart, my lady, you'll wear them yet, for you're too

young to grieve all your days, even for so good a man as my blessed

master. Take comfort, and cheer up, for the dear child's sake if no

more.""I shall never wear them again" was all the answer as Lady

Trevlyn drew the curtains, as if to shut out hope.Sir Richard was buried and, the nine days' gossip over, the

mystery of his death died for want of food, for the only person who

could have explained it was in a state which forbade all allusion

to that tragic day.For a year Lady Trevlyn's reason was in danger. A long fever

left her so weak in mind and body that there was little hope of

recovery, and her days were passed in a state of apathy sad to

witness. She seemed to have forgotten everything, even the shock

which had so sorely stricken her. The sight of her child failed to

rouse her, and month after month slipped by, leaving no trace of

their passage on her mind, and but slightly renovating her feeble

body.Who the stranger was, what his aim in coming, or why he never

reappeared, no one discovered. The contents of the letter left by

Sir Richard were unknown, for the paper had been destroyed by Lady

Trevlyn and no clue could be got from her. Sir Richard had died of

heart disease, the physicians said, though he might have lived

years had no sudden shock assailed him. There were few relatives to

make investigations, and friends soon forgot the sad young widow;

so the years rolled on, and Lillian the heiress grew from infancy

to childhood in the shadow of this mystery.

Chapter II

PAUL"Come, child, the dew is falling, and it is time we went

in.""No, no, Mamma is not rested yet, so I may run down to the

spring if I like." And Lillian, as willful as winsome, vanished

among the tall ferns where deer couched and rabbits

hid.