9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

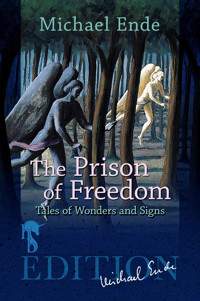

- Herausgeber: hockebooks

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

Michael Ende, the grand master of fantastic literature, captivates with his stories young and old readers from all countries. With the eight stories in this edition, the great storyteller takes the astonished reader into the world of fantasy, into a world full of wonders and signs. In the collection “The Prison of Freedom,” Michael Ende tells of the corridor of an imposing Roman palazzo whose end can never be reached, of a stately villa that can never be entered through its wide, inviting portal—and the story of one who set out to learn how to wonder. Eight astonishing stories full of adventures and fantasy – magnificent, tender, sad and cruel. And even if the magical places where the fantastic stories are set do not exist in reality, we recognize them: they lead into the inner world of each of us who, with the adventures gathered here, embark on an imaginative journey to ourselves.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 313

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Michael Ende

The Prison of Freedom

Tales of Wonders and Signs

Translated by Marshall Yarbrough

The Prison of Freedom

A Long Journey’s End

The Corridor of Borromeo Colmi

The House on the Edge of Town

Admittedly Somewhat Small

The Catacombs of Misraim

From the Chronicles of Max Muto, Dreamworld Traveller

The Prison of Freedom

The Legend of the Waymarker

The Author

A Long Journey’s End

At eight years old Cyril knew all the grand hotels on the European continent and most in the Near East, but beyond this he knew as good as nothing of the world. The porter in his gold-braided uniform, who everywhere wore the same imposing side whiskers and the same peaked cap, was in a manner of speaking the border guard and keeper of the threshold of his childhood.

Cyril’s father, Lord Basil Abercomby, was a diplomat in the service of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. His particular area of responsibility was hard to define, it consisted of so-called special assignments. In any case it involved Lord Abercomby constantly moving from one metropolis to another, without ever staying longer than one or two months in the same place. In order to ensure the requisite level of mobility he contented himself with the smallest possible retinue. This was made up, firstly, of his personal valet Henry; further Miss Twiggle, the governess, an older young woman with horse teeth who was tasked with looking after Cyril’s well-being and teaching him manners; and finally Mr. Ashley, a thin young man of unremarkable character, aside from his tendency to spend his free hours drinking, alone and in silence. He served Lord Abercomby as his personal secretary and at the same time held the job of tutor, that is, of private teacher to Cyril. With the engagement of governess and tutor, Basil had exhausted his interest in paternal care. Once a week he dined alone with his son, but as each of them was intent on not allowing the other to draw any closer to himself, the conversation tended to plod rather laboriously along. Afterwards, both were equally relieved just to have gotten it over with.

Cyril was not a child who inspired sympathy, even going on outward appearance alone. He had—and one would otherwise tend to say this only of an older person—a gaunt body, with a boney, so to speak fleshless physique; brittle, colorless hair; watery, somewhat bulgy eyes; large lips that expressed perpetual dissatisfaction; and an unusually long chin. Most remarkable however for a boy of his age was the complete lack of movement in his face. He wore it like a mask. Most hotel staff took him to be arrogant. Some—above all the chambermaids in mediterranean countries—feared his gaze and avoided meeting him alone.

This was an overreaction, of course, but there was something in Cyril’s character which everyone who came into contact with him came to sense in equal measure and which in equal measure frightened them, and that was his excessive force of will. Fortunately this would only make itself known every now and again, since usually he behaved rather indolently, showed no particular interest in anything and seemed to lack any kind of temperament whatsoever. Thus he could sit all day in the hotel foyer and observe those who arrived and those who left; or he read whatever he might find to read, be it the business pages of a newspaper or a leaflet for bathing cures, and immediately forgot it afterwards. But this indifferent attitude changed instantly whenever he had reached a certain decision. Then there was nothing in the world that could deter him. The cool politesse with which he made his will known permitted no contradiction. Should someone attempt to refuse his command, he would just raise his eyebrows in mild surprise, and not only Miss Twiggle and Mr. Ashley, but even the dignified old valet Henry promptly acceded to his wish. It wasn’t clear to any of them just how the boy did it, and for the boy himself it was something so self-evident that he didn’t think about it.

Once, for example, in the hotel kitchen, which he would wander around in from time to time, to the silent chagrin of the cooks, he saw a live lobster and immediately ordered that it be brought to his room and placed in his bathtub. This was done, even though the crustacean had been ordered for dinner that evening by a guest of the hotel. Cyril observed the strange creature for half an hour, but as it did nothing else but wave its long antennae every now and then, he lost interest, went off and thought nothing more of it. Only that evening, when he went to take a bath, did he remember, and he carried it out to the hallway and set it free. The animal dragged itself under a cabinet and never showed itself again. Only days later did the growing stench of decay alert the hotel staff, who had some trouble tracking down the source of the unpleasant odor. On another occasion Cyril forced the head porter of a Danish hotel to spend several hours building a snowman with him, which then had to be placed in the entrance hall, where it slowly melted away. In Athens, after a piano concert that had taken place in the dining room, he had both grand piano and pianist brought to his room, where he demanded from the unhappy artist that he teach him at once how to play the instrument. Once he was forced to the realization that evidently this would require a more extensive amount of practice, he had a fit of rage the chief victim of which was the piano. Afterwards he became seriously ill and spent several days in bed with a fever. Whenever Lord Basil heard of such eccentric ventures on his son’s part, he seemed more amused than perturbed.

“Well, he’s an Abercomby,” he would comment with indifference. By this he presumably meant to say that in the long succession of their ancestors there had been just about every manner of madman and that for this reason Cyril’s moods were not to be measured against the standard of normal humanity.

Cyril had been born, as it happens, in India, but he could scarcely remember the name of the city, and the country he remembered not at all. His father had at the time had dealings with the consulate there. About his mother, the Lady Olivia, he likewise knew only what Lord Basil had imparted to him in more than curt manner on the single occasion when he had raised a question on the subject, namely that just a few months after his birth she had run off with a street musician. The father quite evidently did not appreciate conversations on this topic in the least, and so the son never asked him again. From Mr. Ashley however he learned later on that it had in no wise been a street musician, but rather the world-renowned violin virtuoso Camillo Berenici, in his time the idol of all the ladies of Europe. But this romance had fallen apart just a year later, which did after all seem to be the course such affairs usually took. It seemed not without pleasure that Mr. Ashley related the matter, perhaps however he was only a bit tipsy and therefore talkative. The societal scandal, he continued, had of course been considerable. Afterwards Lady Olivia had completely withdrawn from the world and ever since had lived more or less in isolation on one of her estates in South Essex. As it happened Lord Basil had never officially divorced her, he had however burned all the pictures and daguerrotypes of his wife in his possession, and her name was—excepting that one occasion—never mentioned by him again. Cyril as a result didn’t even know what his mother looked like.

Why Abercomby carted his son around the world with him instead of sticking him in one of the boarding institutions which for his class were de rigueur was not entirely clear to anyone and gave rise to all manner of speculation. It could scarcely have been paternal affection, for it was known in all quarters that, diplomatic duties excepted, he was interested in one thing and one thing only, namely his collection of weapons and military paraphernalia, which he added to constantly with acquisitions from around the world that he sent to Claystone Manor, the family estate—much to the consternation of the old butler Jonathan, who simply didn’t know where to put it all. In fact the reason was quite simply his concern that Lady Olivia could in some way secretly attempt to establish contact with her child if he didn’t keep a constant eye on the situation. Abercomby was intent on completely ruling out this possibility, not for the boy’s sake, particularly, but rather to punish his spouse for the shame she had brought upon him. Indeed, for this same reason he also throughout all these years avoided returning to England—unless it was purely on official business, and only for a few days, during which time he left his son behind somewhere abroad in the care of the staff.

On one such occasion it happened that the boy surprised his two caregivers in an extremely embarrassing situation. It was late at night when he woke for one reason or another and called for the governess, who slept in the neighboring room. Since he received no answer, he got up and went to investigate. Miss Twiggle’s bed was still made. He set out in search of her. As he went past his tutor’s room, he heard strange, muffled noises. Carefully he opened the door. What he saw interested him, and so, unnoticed, he stepped inside, took a seat on a chair and observed the scene attentively. Mr. Ashley and Miss Twiggle, both mostly undressed, were rolling around on the carpet, limbs entwined as if in a wrestling match, while he made grunting and she squeaking noises. On the table stood an empty whiskey bottle and two half-full glasses. After a while the two seemed to tire and they came to a stop, panting. Cyril coughed discreetly. The two of them shot up in fright and stared at him, faces flushed. He didn’t quite know what to make of the matter, but in the looks both of them gave him he read shame and guilt. That was enough for him. He rose and went back to his room, not saying a word. Neither of them mentioned the incident in the days that followed, and Cyril said nothing either. To the already amply helpless behavior of the governess and the tutor was added from then on a kind of subservience, which Cyril thoroughly enjoyed. Even if he didn’t know exactly why, still he felt quite clearly that, morally speaking, he had the two of them under his thumb. To emphasize the distance between them and him, from that point forward he insisted upon having a table to himself at dinner. It did not bother him in the least that he was stared at by all the other hotel guests, secretly or quite unabashedly, like a strange animal at the zoo. Afterwards he would sit for an hour or two in the lounge, again mostly alone. When Miss Twiggle would timidly ask him to please go to bed, he would summarily forbid her from speaking and send her away. He sat in his seat like someone who was just passing the time till his life was finally over. And as a matter of fact Cyril was waiting. Really he had been waiting ever since he had come into this world, he just didn’t know what for.

This changed when, one evening at the Hotel Inghilterra in Rome, he was wandering through the carpeted hallways and heard muffled but heartbreaking sobs coming from a window recess that was obscured by potted palms with large fronds. Treading softly, he approached and discovered a little girl, around his age, who was cowering in one of the large leather fauteuils, her knees drawn up to her chest, her face pressed into an armrest and covered in tears. The spectacle of such an uninhibited emotional outburst was new and astounding for him. He regarded it for a while in silence before he finally asked: “Is there anything I can do for you, Miss?”

She turned her teary face towards him, shot him a scornful look and snapped: “Stop staring at me, fish face! Leave me alone!”

She had spoken English, but in a clipped, curiously flat-sounding manner that he had not heard before.

“I’m sorry, Miss,” he answered with a little bow, “I didn’t mean to disturb you.”

She seemed to be waiting for him to go, but he did not do so.

“Get lost already,” she sniffed. “Mind your own business.” Despite her coarse words she sounded a bit less unfriendly now.

“Certainly,” he said, “I understand completely, Miss. Would you allow me to sit for a moment?”

She gave him a doubtful look—it wasn’t clear to her whether he was making fun of her or not. Then she shrugged her shoulders. “Oh, do whatever you want. They’re not my chairs.”

He sat down across from her and watched as she wiped her nose.

“Has someone wronged you somehow, Miss?” he inquired finally.

The girl snorted. “Yeah, Aunt Ann. She talked me into coming on this awful trip to Europe. And now we’ve been away from home for almost four months, four months, you understand, because she paid for everything in advance, and it was a whole lot of money, and she says she’s not going to just throw it all out the window only on account of me.”

Cyril pondered this for a while, then he said: “I must confess, Miss, I don’t see what could be so exceedingly painful in that.”

“Ugh,” she exclaimed impatiently, “I’m just homesick, that’s all, really terribly homesick.”

“You’re—what?” he asked, not understanding.

The girl kept on nattering away, as if she hadn’t heard Cyril’s question. “If only she’d at least let me go back by myself! It’s not like I’m asking her to come with me. I’d just take the next ship and sail back home. It makes no difference to me how long it takes, it would at least be the right direction. I would feel better right away, every day a little more. Mom and Dad could maybe pick me up in New York, since I’m not so good with the trains.”

“So you are sick, Miss?” Cyril inquired.

“Yes . . . no . . . oh, what do I know?” She gave him an angry look. “One thing’s for certain anyway. If I can’t go home right away, then I’ll die.”

“Really?” he asked, interested. “And why is that?”

And now she told him about a small town somewhere in the United States, in the Midwest, where her father and her mother lived along with her two younger siblings, Tom and Abby, and Sarah, the stout old black woman, who knew so many songs and ghost stories, and her little dog Fips, who could catch rats and once had even gotten into it with a badger, and about the big woods behind the house, where there were some kind of special berries, and about a certain Mr. Cunnigle, who had a store in the next town where you could buy simply everything and where it smelled like this and that, and about a thousand other completely trivial things. As she talked she grew more excited, it seemed to really do her good to mention every single detail, however unimportant.

Cyril listened and tried to figure out just what the devil made any of it so special that no one in the world could stand to be away from it for even a few months. The girl on the other hand seemed to feel she was understood, because finally she thanked him for his interest and invited him to stop by if he ever found himself in the area. Then the little girl left, clearly consoled and relieved. He hadn’t even learned her name.

The next day she and her aunt had probably left already; he couldn’t find her anywhere, and didn’t want to ask after her. Really she herself didn’t matter to him at all. What preoccupied him was much more the girl’s curious condition, which she had called homesickness and which he couldn’t even begin to imagine. For the first time he became dimly aware that he had never possessed anything like a home, nothing at all for which he could have longed and pined away. There was something he was missing, that was plain enough, but what he couldn’t get clear on was whether this was an advantage or a deficiency. He decided to look into the matter.

He didn’t mention anything about it to Mr. Ashley or Miss Twiggle, and certainly not to his father, but from now on he frequently tried to engage strangers in conversation. Sooner or later he would steer the conversation in such a way that they would start talking about their home. It made no difference to him whether it was a child or an elderly lady or gentleman he was speaking to, whether the chambermaid, the page or the hotel manager, because he realized quite quickly that they all, without exception, seemed happy to talk about it, that often a smile would brighten their faces. Some grew glassy-eyed and effusive, others were filled with melancholy, but the matter seemed to mean a lot to each of them. Although the particular details were different with every person, the accounts also resembled one another in one particular respect. There was never something unique, something special involved, something that would have justified such an outpouring of emotion. And something else occurred to him as well: By no means did this “home” have to be the place where someone was born. Neither, however, was it identical with the place where the person was living now. By what was it determined, then, and by whom? Did everyone do it at their own discretion? But then why didn’t he have anything of the kind? Evidently, every person except for him possessed something like a sanctum, a treasure, whose worth, to be sure, did not rest on anything tangible, not on anything you could pin down, but which nevertheless was reality. The thought that he of all people should be denied such a possession seemed completely unbearable to him. He was willing to pay any price to get it. After all, somewhere in the world, there had to be something like it for him, too.

Cyril obtained permission from his father to undertake extended outings beyond the confines of whichever hotel they happened to be staying in. Though permission was granted him, it was under the strict condition that he undertake such excursions only when accompanied by Mr. Ashley, Miss Twiggle, or the two of them together.

There were a few initial undertakings with all three of them, but it quickly grew wearisome for Cyril, as the two caregivers were concerned primarily with each other. Miss Twiggle seemed for some unfathomable reason to be suffering terribly, with Mr. Ashley being the cause. Every word she spoke contained a reproach directed towards him. Mr. Ashley for his part replied with coldness and derision. Cyril didn’t think much of either of them, but if he was going to have to choose—and this seemed unavoidable—then for his particular purposes he preferred Mr. Ashley. To the surprise and also somewhat to the annoyance of the tutor, who by that point had become accustomed to pursuing his own not always entirely virtuous amusements outside the hours spent teaching or performing his secretarial duties, Cyril seemed determined thenceforth to follow him everywhere he went. Mr. Ashley, who of course didn’t know his pupil’s true motives, inwardly sighed, but on the other hand was even a bit proud, because he regarded this suddenly awakened interest for people and place as the result of his years of pedagogical efforts.

At first he confined himself to showing his charge the scenic avenues and plazas, the palaces, churches, temple ruins and other noteworthy sights which at that time formed the educational standard of every Englishman abroad. Cyril regarded everything with a certain probing attentiveness, but what he saw seemed to leave him cold. In order to meet the boy’s unvoiced expectation, Mr. Ashley went further and together they ventured out into less familiar territory, to slums and poor quarters, dockyards and seedy taverns, but also, outside the cities, to mountains and bays, deserts and forests. During these shared ventures something like a comradely relationship formed between the two of them, which eventually led Mr. Ashley to bring his young pupil along not only to cock fights and dog races, but also to cabaret shows and even more dubious entertainments. When he was finally certain that he could count on Cyril’s discretion, and because it was absolutely impossible to get rid of him, they even began to wind up from time to time in houses of a certain sort, where the boy had to wait in the salon for his teacher to return from an urgent private discussion with one of the women employed there.

Cyril took all of this in with the same immobile expression, for a home, as he had learned from his countless conversations, could be anywhere at all. But it was in vain that he waited for some occasion when he would feel happy or sad. Nothing, of all the things he saw, meant anything to him. But of course he kept that to himself.

These questionable educational field trips naturally could not remain hidden from his father in the long run. Indeed, rumors of them had long spread throughout all of Victorian society and set off the expected uproar, it was only Lord Abercomby who was, as is so often the case, clueless. Late one evening, however—it was a few days after Cyril’s twelfth birthday—father and son encountered one another in an établissement of the Madrid demimonde which happened to be fashionable at that time. The boy sat in the front room on an oriental divan under draperies and peacock feathers. Spread out around him were four young ladies reclining in negligees, who were chatting with him excitedly and—what else?—each talking about their respective homes. Lord Abercomby strode past his son without a word, as if he didn’t know him, and left the house of vice. The next day however Cyril learned at five o’clock tea that his tutor had been dismissed, effective immediately. Beyond this not a word was exchanged between father and son about the incident; it was an era of strict morals. Two days later Miss Twiggle gave notice to Lord Basil, her face composed but her nose red from crying. When she was alone with Cyril she confessed to him: “You probably cannot understand all this yet, my dear. But Max—I mean Mr. Ashley—is the love of my life. I shall follow him wherever he goes, be it into poverty or into death. Think of me—later, when you yourself shall love.” Then she tried to kiss him goodbye, which Cyril successfully prevented.

The search for a new tutor and a new governess soon proved unnecessary, because just three weeks later Lord Basil received a telegraph with the news that Lady Olivia had passed away from a protracted illness that she had likely brought back from India. Father and son traveled back to South Essex without delay and attended the solemn funeral, which, and no one could have expected otherwise, took place under pouring rain. This was the first time that Cyril had set foot on English soil. If he had possibly expected that any kind of home-related emotions, however faint, would come over him, he was mistaken. Even the family seat of the Abercombys, Claystone Manor, to which his father and he traveled after the funeral, was no more than a disappointment to him. This dark, hulking pile, packed full of weapons, which in comparison with the international hotels provided as good as no comfort and in which one was always freezing, was and remained perfectly alien to him.

Lord Abercomby concealed from his progeny the fact that his mother had named him, her son, whom she had never laid eyes on except during the span of a few months after his birth, the sole heir to all her possessions. He planned to inform him of this only on the day of his coming of age, in order to prevent even the possibility of his developing any childish feelings of gratitude. This too was part of his punishment—albeit by then posthumous—for his unfaithful wife.

As he was now spared the necessity of having to cart the boy around the world with him, he stuck him without further ado in one of the renowned educational institutions for the upper class, the college in E., where English boys are groomed to become English men. Cyril subjected himself to the unpleasantries of pedagogy with a certain contemptuous indolence; he made his classmates, and above all his teachers, feel quite clearly that he really did not take any of them seriously. Since however he was an outstanding student—by this time he already spoke eight languages nearly flawlessly—he was regarded as the leading light of the college, this even though no one could particularly stand him. After gaining his diploma he went on to O., as was customary for someone of his class, and began to study philosophy and history at the university there.

After a few semesters—and curiously enough it was again shortly after his birthday, this time his twenty-first—he received a surprising visit from Mr. Thorne, the family’s solicitor. Out of breath, the old gentlemen sat down and began speaking circuitously, trying to prepare the young man for what he called a “tragic event.” While fox hunting in the vicinity of Fontainebleau, Lord Basil Abercomby had taken an unlucky fall from his horse, so unlucky in fact that he had broken his neck. As he received the news Cyril’s face remained fixed.

“You are now therefore,” said Mr. Thorne, and patted his forehead and double chin dry with a handkerchief, “not only heir to the title held by your esteemed father, but also the sole heir to your father’s as well as your mother’s fortunes, the owner of all properties, both real and personal, belonging to both estates—for you, my dear young friend, are the sole descendant of both families. I have taken the liberty of bringing to you all pertinent documents, records, inventories and balance sheets, so that you, should you wish to do so, can examine them forthwith.”

He produced a heavy briefcase and hefted it onto his knee.

“Thank you,” said Cyril, “please don’t bother.”

“Oh, I understand,” said Mr. Thorne, “we’ll sort it out at a later time. Forgive me, I didn’t mean to be disrespectful. Do you have any particular wishes with regard to the burial ceremony?”

“Not that I can think of,” replied Cyril. “I leave it to you. You’ll see to it that the necessary steps are taken, I’m sure.”

“Certainly, my lord. When do you intend to depart?”

“Depart? Going where?”

“Why, to your father’s funeral, I should think.”

“My dear Mr. Thorne,” said Cyril, “I don’t see why I should subject myself to such a thing. God forbid. I loathe such occasions. Do with the corpse whatever you deem proper.”

The solicitor coughed, his face turned red. “Now then, certainly—” he said, visibly making an effort to compose himself, “it is of course an open secret that you and your father were not, how should I say, on ideal terms, but nevertheless, I mean, now that he has passed on—forgive me if I permit myself to remind you that there do exist such things as one’s filial duty.”

“Oh?” asked Cyril and raised his eyebrows a little.

Unsure what to do, Mr. Thorne opened his briefcase, hesitated, and closed it again. “Please do not misunderstand me, sir. This is most certainly your own, personal decision. I only meant to point out that society will be following every particular of such an event.”

“Will it now?” Cyril answered, bored.

“Yes, well, good then,” said Mr. Thorne, “and as regards the matter of inheritance, I suggest . . .”

“Sell it all,” Cyril cut him off mid-sentence.

The solicitor froze and stared at him, mouth agape.

“Yes,” Cyril continued. “You heard right, my good man. I don’t want to keep any of it. Turn everything into cash that isn’t cash already. You’re sure to know how best to arrange such things.”

“You mean,” Mr. Thorne blurted out, “the estates, the woodlands, the castles, the artworks, your father’s collection . . . ?”

Cyril gave a curt nod. “Get rid of it. Sell.”

The old man was fighting for air, like a fish on dry land. His face turned purple.

“We’ll want to think quite carefully about this, my lord. Right now we are perhaps allowing our emotions to affect our thinking, which . . . that is, to speak quite plainly, my lord: you cannot do this. This is not done, not under any circumstances. For forty-five years now I have been your family’s personal solicitor, and I must tell you, this would be . . . this would . . . it would go against every . . . please consider that we are talking about a legacy that your ancestors have accumulated over the course of centuries . . . no, listen to me, Cyril, if I may call you that, you are morally obligated to pass it all on to your own descendants . . .”

The young lord abruptly turned his back to him and looked out the window. Coolly, but with impatience evident in his voice, he replied: “I won’t have any descendants.”

The lawyer raised his fat hands to brush this aside. “Dear boy, one cannot be so certain of that at your age. It could well be . . .”

“No,” Cyril interrupted him sharply, “it could not be. And don’t call me dear boy.”

He turned towards him again and looked at him coldly. “If you have an insurmountably strong conscience, Mr. Thorne, then it will not be hard to find someone else for the job. Good day.”

Mr. Thorne, exceedingly incensed at the shameless treatment which he had so undeservedly received, was at first resolved not to take on this, as he called it, “immoral and unconscionable business.” But during the return trip to London his indignation was already giving way to clear and rational consideration. And after he had conferred at length over the following two days with his two partners, Saymor and Puddleby, he realized that the—perfectly legal—profit that was to be expected from the commission alone on sales of this magnitude by far exceeded any harm that might be done to the up to now spotless reputation of their firm by their involvement in the scandal that was bound to ensue.

In a written statement to the young lord that was filled with ample terms and conditions, Mr. Thorne & Co. declared that they were prepared forthwith to oversee the execution of the business. The statement, signed by Cyril Abercomby, was returned to them immediately by post. The matter took its course.

When society at large learned of it—which of course was unavoidable, really—a torrent of outrage broke loose. Not only did the higher ranks of the nobility and the combined upper classes of the kingdom unanimously voice their utmost disgust at such an unheard of lack of respect for tradition and disregard for one’s own rank, Parliament was also occupied with the matter for several days; yes, even in the pubs of the lower classes there were various heated discussions on the question of whether such a person even had the right to still call himself a subject of Her Majesty the Queen. Judicially speaking however there was no legal cause to oppose this “bargain sale of English culture and dignity,” as several newspapers called it—in formulating all the conditions, Mr. Thorne & Co. had had the wisdom and foresight to make sure of this.

Cyril himself was entirely apathetic towards all the uproar he had caused. He had promptly broken off his studies, which indeed he had only just begun, and had long since left the country. In the following years he traveled the cities and countries of the world without any particular destination in mind, led only by inclination and happenstance, but now he no longer traveled only in Europe and the Near East, as when his father was alive, but also throughout Africa, India, South America and the Far East. And all the while he was bored nearly to death, for neither landscapes nor architecture, neither oceans nor the traditions and customs of foreign peoples aroused in him anything more than superficial interest. It was scarcely worth leaving the comfort of the grand hotel, even just provisionally. Since he could not find the secret of where he belonged anywhere in this world, all other wonders were dull and meaningless to him.

His sole companion on these aimless journeys was a servant named Wang, whom he had bought from the head of an opium syndicate in Hong Kong. Wang possessed the almost supernatural ability to not exist when he wasn’t needed, but to always be at hand when his master required his services. He also seemed to know his desires in advance, so that they scarcely needed to exchange a word with one another.

Among the English aristocracy there had at first been a tacit agreement to boycott the sale of the Abercomby estate, but they were soon made to think better—or, if you will—worse of it. A not inconsiderable amount of interested parties from outside the country stepped into the fray and with their offers drove the prices up. And when finally, after a minimum of negotiation, an American rubber tycoon by the name of Jason Popey purchased Claystone Manor together with everything inside and surrounding it—he even took on the old butler Jonathan—it came as a shock to national pride. In order to save what still could be saved, there began among the ranks of rich and powerful families of the empire a veritable run on whatever was still to be had. To the credit of Mr. Thorne & Co. it must be said that they gave preference to such buyers, even if in some instances it was necessary to come down a little in price. In any case, just three years after the death of his father, the young Lord Abercomby numbered among the hundred richest men on this Earth—at least where his bank balance was concerned.

Little by little the storm subsided, and society moved on to other topics of conversation. The one question that still served to occupy certain souls—above all mothers whose daughters were of marriageable age—was just what Cyril Abercomby could be thinking of doing with this ungodly amount of money. As far as anyone knew he didn’t indulge in games of chance, nor did he take part in gambling of any kind. Nor did he have some other expensive passion, such as for example collecting Ming vases or Indian jewels. He dressed impeccably, but without extravagance. He lived as befitted his station, but only ever in hotels. He kept no expensive lovers and did not give himself over to other, more discrete vices. What did he plan to do with the money? No one knew, and himself least of all.

Throughout the next decade Cyril continued his restless life of travel. He had by this point become so accustomed to what he called “his quest” that for him it had become a natural way of being, one he didn’t question. Naturally he had long ago lost the naïve hope of his young days that somewhere or sometime he would actually find what he was looking for. Indeed it was quite the opposite, by then he didn’t want it anymore, it would have been acutely embarrassing to him. He had devised the following formula for his situation: The length of the journey lies in inversely proportional relation to the probability of ever wanting to reach the end. – Precisely therein lay, in his view, the irony of all human endeavor: the actual meaning of all expectation was entirely premised on its remaining forever unfulfilled, since all fulfillment must in the end lead only to disappointment. Yes, God himself did well never to make good on any of the promises he made to humanity long ago. Even assuming that one ill-fated day he got the idea of seriously following through with it—the Messiah actually appeared in the clouds, the Final Judgement actually took place, Heavenly Jerusalem actually descended from above—it couldn’t end up being anything but a cosmic disgrace. He had kept his believers waiting too long for any event, no matter how bombastic, to still be able to draw any reaction from them now other than a general “Oh, that was it?” On the other hand it was undoubtedly wise of God (always assuming that he existed at all) to never rescind his promise. For the expectation, and the expectation alone, was what kept the world in motion.

For one who had in this manner caught a glimpse at the hand of fate, it was naturally not so easy to continue playing the game. But Cyril did so nonetheless, and even with a certain scornful pleasure. He was conscious of his belonging to the order of those who are eternally dissatisfied, who had imagined every ocean wider, every mountain higher, every sky bigger, but he was in no way unhappy on this account. It was simply that his indifference towards the world and other people now also extended to himself, to his own life: it no longer meant much to him, not, however, that he would ever have felt the desire to do away with himself because of this.