1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

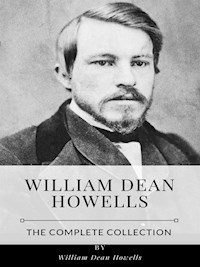

In "The Register," William Dean Howells deftly explores the intersection of personal identity and societal expectation within the backdrop of 19th-century America. With a style that marries realism with psychological depth, Howells crafts a narrative that scrutinizes the nuances of human emotion and social dynamics. The dialogue-driven structure and rich character development reflect the burgeoning literary trend of realism, inviting readers into a world where every individual's voice contributes to the larger socio-cultural discourse of the time. Throughout the novel, Howells'Äôs acute observations on American life are interwoven with a subtle critique of social conventions, making it a significant work in his oeuvre. William Dean Howells, often referred to as the "Dean of American Letters," was a prominent literary figure who championed realism in American literature. His extensive experience as a literary critic and editor, coupled with his personal encounters within diverse societal circles, provided him with the insights necessary to explore the complexity of human relationships. Howells'Äôs life, marked by intellectual prowess and a keen awareness of the social landscape, significantly informed his writing, particularly in "The Register," which echoes his commitment to authenticity and truth in art. Readers seeking a profound engagement with the themes of identity and societal roles will find "The Register" an illuminating experience. Howells'Äôs meticulous attention to detail and his ability to capture the subtleties of human interaction invite reflection and dialogue, making this novel a crucial read for those interested in the evolution of American literature and the complexities of its characters. Delve into Howells'Äôs world and appreciate the robust interplay between individual desires and societal pressures.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

The Register

Table of Contents

I.

Scene: In an upper chamber of a boarding-house in Melanchthon Place, Boston, a mature, plain young lady, with every appearance of establishing herself in the room for the first time, moves about, bestowing little touches of decoration here and there, and talking with another young lady, whose voice comes through the open doorway of an inner room.

Miss Ethel Reed, from within: “What in the world are you doing, Nettie?”

Miss Henrietta Spaulding: “Oh, sticking up a household god or two. What are you doing?”

Miss Reed: “Despairing.”

Miss Spaulding: “Still?”

Miss Reed, tragically: “Still! How soon did you expect me to stop? I am here on the sofa, where I flung myself two hours ago, and I don’t think I shall ever get up. There is no reason why I ever should.”

Miss Spaulding, suggestively: “Dinner.”

Miss Reed: “Oh, dinner! Dinner, to a broken heart!”

Miss Spaulding: “I don’t believe your heart is broken.”

Miss Reed: “But I tell you it is! I ought to know when my own heart is broken, I should hope. What makes you think it isn’t?”

Miss Spaulding: “Oh, it’s happened so often!”

Miss Reed: “But this is a real case. You ought to feel my forehead. It’s as hot!”

Miss Spaulding: “You ought to get up and help me put this room to rights, and then you would feel better.”

Miss Reed: “No; I should feel worse. The idea of household gods makes me sick. Sylvan deities are what I want; the great god Pan among the cat-tails and arrow-heads in the ‘ma’sh’ at Ponkwasset; the dryads of the birch woods—there are no oaks; the nymphs that haunt the heights and hollows of the dear old mountain; the”—

Miss Spaulding: “Wha-a-at? I can’t hear a word you say.”

Miss Reed: “That’s because you keep fussing about so. Why don’t you be quiet, if you want to hear?” She lifts her voice to its highest pitch, with a pause for distinctness between the words: “I’m heart-broken for—Ponkwasset. The dryads—of the—birch woods. The nymphs—and the great—god—Pan—in the reeds—by the river. And all—that—sort of—thing!”

Miss Spaulding: “You know very well you’re not.”

Miss Reed: “I’m not? What’s the reason I’m not? Then, what am I heart-broken for?”

Miss Spaulding: “You’re not heart-broken at all. You know very well that he’ll call before we’ve been here twenty-four hours.”

Miss Reed: “Who?”

Miss Spaulding: “The great god Pan.”

Miss Reed: “Oh, how cruel you are, to mock me so! Come in here, and sympathize a little! Do, Nettie.”

Miss Spaulding: “No; you come out here and utilize a little. I’m acting for your best good, as they say at Ponkwasset.”

Miss Reed: “When they want to be disagreeable!”

Miss Spaulding: “If this room isn’t in order by the time he calls, you’ll be everlastingly disgraced.”

Miss Reed: “I’m that now. I can’t be more so—there’s that comfort. What makes you think he’ll call?”

Miss Spaulding: “Because he’s a gentleman, and will want to apologize. He behaved very rudely to you.”

Miss Reed: “No, Nettie; I behaved rudely to him. Yes! Besides, if he behaved rudely, he was no gentleman. It’s a contradiction in terms, don’t you see? But I’ll tell you what I’m going to do if he comes. I’m going to show a proper spirit for once in my life. I’m going to refuse to see him. You’ve got to see him.”

Miss Spaulding: “Nonsense!”

Miss Reed: “Why nonsense? Oh, why? Expound!”

Miss Spaulding: “Because he wasn’t rude to me, and he doesn’t want to see me. Because I’m plain, and you’re pretty.”

Miss Reed: “I’m not! You know it perfectly well. I’m hideous.”

Miss Spaulding: “Because I’m poor, and you’re a person of independent property.”

Miss Reed: “Dependent property, I should call it: just enough to be useless on! But that’s insulting to him. How can you say it’s because I have a little money?”

Miss Spaulding: “Well, then, I won’t. I take it back. I’ll say it’s because you’re young, and I’m old.”

Miss Reed: “You’re not old. You’re as young as anybody, Nettie Spaulding. And you know I’m not young; I’m twenty-seven, if I’m a day. I’m just dropping into the grave. But I can’t argue with you, miles off so, any longer.” Miss Reed appears at the open door, dragging languidly after her the shawl which she had evidently drawn round her on the sofa; her fair hair is a little disordered, and she presses it into shape with one hand as she comes forward; a lovely flush vies with a heavenly pallor in her cheeks; she looks a little pensive in the arching eyebrows, and a little humorous about the dimpled mouth. “Now I can prove that you are entirely wrong. Where—were you?—This room is rather an improvement over the one we had last winter. There is more of a view”—she goes to the window—“of the houses across the Place; and I always think the swell front gives a pretty shape to a room. I’m sorry they’ve stopped building them. Your piano goes very nicely into that little alcove. Yes, we’re quite palatial. And, on the whole, I’m glad there’s no fireplace. It’s a pleasure at times; but for the most part it’s a vanity and a vexation, getting dust and ashes over everything. Yes; after all, give me the good old-fashioned, clean, convenient register! Ugh! My feet are like ice.” She pulls an easy-chair up to the register in the corner of the room, and pushes open its valves with the toe of her slipper. As she settles herself luxuriously in the chair, and poises her feet daintily over the register: “Ah, this is something like! Henrietta Spaulding, ma’am! Did I ever tell you that you were the best friend I have in the world?”

Miss Spaulding, who continues her work of arranging the room: “Often.”

Miss Reed: “Did you ever believe it?”

Miss Spaulding: “Never.”

Miss Reed: “Why?”

Miss Spaulding, thoughtfully regarding a vase which she holds in her hand, after several times shifting it from a bracket to the corner of her piano and back: “I wish I could tell where you do look best!”

Miss Reed, leaning forward wistfully, with her hands clasped and resting on her knees: “I wish you would tell me why you don’t believe you’re the best friend I have in the world.”

Miss Spaulding, finally placing the vase on the bracket: “Because you’ve said so too often.”

Miss Reed: “Oh, that’s no reason! I can prove to you that you are. Who else but you would have taken in a homeless and friendless creature like me, and let her stay bothering round in demoralizing idleness, while you were seriously teaching the young idea how to drub the piano?”