Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

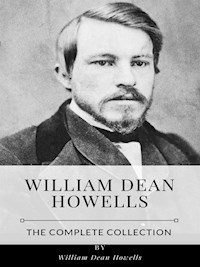

Mr. Howells is at his best in this novel. There is in it the same perfection of finish, the same absolute sureness of technique, the same realism (to use an overworked word, but here used in its true sense, not meaning either nastiness or stupidity) which one is always sure to find in his work. But there is something more in this book than in some of his others — more strength, more interest, and a bigger, and successful, attempt to show the more emotional and more vital side of life. The plot is almost precisely that of Ibsen's "Ghosts," with the very great difference, however, that the young man turns out well, and the book ends happily, instead of in the sickening horror of the Ibsen play. Langbrith senior, dead before the story opens, had been a vicious and criminal man in all respects; his widow had allowed their son to come to manhood as a hero-worshipper of his father, knowing that it was wrong, but never having the courage to tell him the true state of affairs. The son is in love with, and is loved by, the daughter of the man whom his father has most wronged. In a quarrel with his uncle the young man is told what his father really was. This terrible blow overturns his whole attitude toward life. He wishes to sacrifice everyone by confession to the world, but is wisely and sanely persuaded that it is best to bear his burden as it is, till the fitting, not Quixotic, time for disclosure arrives. In his trouble, all the characters show their sweetness and strength in helping him to bear the burden. So meagre an outline of the story necessarily means little ; but imagine this plot filled in with every delicacy and sweetness, with fine character-drawing, with real humanity, and with that beautiful and tolerant point of view of life which has come to Mr. Howells in his old age, and you can easily see how fine a novel is 'The Son of Royal Langbrith', how well worth reading it is by everyone who cares for the best in fiction.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 438

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Son Of Royal Langbrith

WILLIAM DEAN HOWELLS

The Son of Royal Langbrith, W. D. Howells

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Deutschland

ISBN: 9783849657772

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

CONTENTS:

I.1

II4

III.7

IV.. 10

V.. 13

VI17

VII21

VIII25

IX.. 30

X.. 33

XI37

XII41

XIII47

XIV.. 56

XV.. 64

XVI67

XVII76

XVIII84

XIX.. 88

XX.. 93

XXI98

XXII103

XXIII109

XXIV.. 115

XXV.. 121

XXVI128

XXVII134

XXVIII140

XXIX.. 144

XXX.. 149

XXXI153

XXXII158

XXXIII166

XXXIV.. 170

XXXV.. 175

XXXVI183

XXXVII187

I.

“We’re neither of us young people, I know, and I can very well believe that you had not thought of marrying again. I can account for your surprise at my offer, even your disgust—” Dr. Anther hesitated.

“Oh no!” Mrs. Langbrith protested.

“But I can’t see why it should be ‘terrible,’ as you call it. If you had asked me simply to take ‘ no ’ for an answer, I could have taken it. Or taken it better.’’

He looked at her with a wounded air, and she said, “I didn’t mean ‘terrible’ in that way. I was only thinking of it for myself, or not so much myself as — someone.” She glanced at him, where, tenderly indignant with her, he stood by the window, quite across the room, and she seemed to wish to say more, but let her eyes drop without saying more.

He was silent, too, for a time which he allowed to prolong itself in the apparent expectation that she would break their silence. But he had to speak first. “I don’t like mysteries. I can forget—or ignore—any sense of ‘ terrible ’ you had in mind, if you will tell me one thing. Do you ask me now to take simply ‘no’ for an answer?”

‘‘Oh no!” The words were as if surprised from her, and she made with her catching breath as if she would have caught them back.

He came quickly across the room to her. “ What is it, Amelia?”

“ I can’t tell you,” she shuddered out, and she recoiled, pulling herself up, as if she wished to escape but felt an impenetrable hinderance at her back. In the action, she showed taller than she was, and more girlishly slender. At forty, after her wifehood of three years and her widowhood of nineteen years, the inextinguishable innocence of girlhood, which keeps itself through all the experiences of a good woman’s life, was pathetic in her appealing eyes; and the mourning, subdued to the paler shades of purple, which she permanently wore, would have made a stranger think of an orphan rather than a widow in her presence.

Anther’s burly frame arrested itself at her recoil. His florid face, clean shaven at a time when nearly all men wore beards, was roughed to a sort of community of tint with his brown overcoat by the weather of many winters’ and summers’ driving in his country practice. His iron-gray hair, worn longer than the fashion was in towns, fell down his temples and neck from under his soft hat. He had on his driving gloves, and he had his whip in one hand. He had followed Mrs. Langbrith indoors in that figure from the gate, where his unkempt old horse stood with his mud spattered buggy, to pursue the question which she tried rather than wished to shun, and he did not know that he had not uncovered. At the pathos in her eyes and in her cheeks, which had the vertical hollows showing oftener in youth than in later life, the harshness of gathered will went out of his face. “ I know what you mean,” he said; and at his words the tears began to drip down her face without the movement of any muscle in it, as if a habit of self-control which enabled her to command the inward effects of emotion had not been able to extend itself to its displays. “Poor thing!” he pitied her. “Must you always have a tyrant?”

“He isn’t a tyrant,” she said.

“Oh yes, he is! I know the type. I dare say he doesn’t hit you, but he terrorizes you.”

Mrs. Langbrith did not speak. In her reticence, even her tears stopped.

“You tempt him to bully you. Lord bless me, you tempt me! But I won’t; no, I won’t. Amelia, why, in Heaven’s name, should he object? He has his own interests, quite apart from yours; his own world, which you couldn’t enter if he would let you. A fellow in his junior year at college is as remote from his mother in everything as if he were in another planet!”

“We write to each other every Sunday,” she urged, diffidently.

“ I have no doubt you try to keep along with him; that’s your nature; but I know that he cowed you before he left home, and I know that he cows you still. I could read your correspondence—the spirit -—without seeing it. He isn’t to blame. You’ve let him walk over you till he thinks there is no other path to manhood. Remember, I don’t say Jim is a bad fellow. He is a very good fellow—considering.”

The doctor went to the window and stooped to look out at his horse, which remained as he had left it, only more patiently sunken in a permanence expressed by the collapsing of its hind quarters into a comfortable droop, and a dreamy dejection of its large head. In the meantime, Mrs. Langbrith had sat down in a chair which she seemed to think had offered itself to her, and when the doctor came back, he asked, “May I sit down?”

“Why, of course! I’m ashamed—”

“No, no! Don’t say that! Don’t say anything like that!”

In the act of sitting down, he realized that he had his hat on. He took it off and put it on the floor near his feet, where it toppled into a soft heap. His hair had partly lifted with it, and its disorder on his crown somewhat concealed its thinness. “ I want to talk this matter over sensibly. We are not two young things that we need be scared at our own feelings, or each other’s. I suppose I may say we both knew it was coming to something like this?”

She might not have let him say so for her, but in her silence, he went on to say so for himself.

“I knew it was coming, anyway, and I’ve known it for a good while. I have liked you ever since I came to Saxmills she trembled and colored a little—“but I wouldn’t be saying what I am saying to you, if I had cared for you before Langbrith died as I care for you now. That would be, to my thinking, rather loathsome. I should despise myself for it; I should despise you; I couldn’t help it. But we are both fairly outside of that. I didn’t begin to realize how it was with me till about a year ago, and I don’t suppose that you—’’

Mrs. Langbrith shifted her position slightly, but he did not notice, and he began again.

“ So I feel that I can offer you a clean hand. I’m six years older than you are, which makes it just about right; and I’m not so poor that I need seem to be after your—thirds. I’ve got a good practice, and I don’t intend to take life so hard hereafter. I could give you as pleasant a home—”

“Oh, I couldn’t think of leaving this!” she broke out, helplessly.

Anther allowed himself to smile. “Well, well, there’s no hurry. But if Jim marries—”

“ I should live with him.”

“ I’m imagining that you would live with me.”

“You mustn’t.”

“I’m merely imagining; I’m not trying to commit you to anything, or to overrule you at all. My idea is, that there’s been enough of that in your life. I want you to overrule me, and if you don’t fancy settling down immediately, and would like a year or two in Europe first, I could freshen my science up in Vienna or Paris, and come back all the better prepared to keep on in my practice here, or I could give up my practice altogether.”

“You oughtn’t to do that.”

“ No, I oughtn’t. But all this is neither here nor there, till the great point is settled. Do you think anyone could care for me as I care for you?

“Why, of course, Dr. Anther?”

“Do you care for me—that way—now?” He seemed to expect evasion or hesitation, even such elusion as might have expressed itself in material escape from him, and, unconsciously, he hitched his chair forward as if to hem her in.

It was a needless precaution. She answered instantly, “You know I do.”

“Amelia,” Anther asked solemnly, without changing his posture or the slant of his face in its lift towards hers, “have I put any pressure on you to say this? Do you say it as freely as if I hadn’t asked you?”

The absurdity of the question did not appear to either of them. She answered, “I say it as freely as if it had never been asked. I would have said it years ago. I have always liked you—that way. Or ever since—”

He leaned back in his chair and pushed his hands forward on the arms. “ Then—then—’” he began, bewilderedly, and she said:

“But—”

“Ah!” he broke out, “I know what that ‘but’ means. Why need there be any such ‘but’? Do you think he dislikes me?”

“ No, he likes you; he respects you. He says you are a physician who would be famous in a large place. He—”

Anther put the rest aside with his hand. “Then he would object to anyone? Is that it?’’

“Yes,’’ said Mrs. Langbrith, with a drop to specific despair from her general hopelessness.

“ I don’t recognize his right,” Anther said sharply, “unless he is ready to promise that he will never leave you to be pushed aside; turned from a mother into a mother-in-law. I don’t recognize his right. Why does he assume such a right?”

“ Out of reverence for his father’s memory.”

II

One cannot look on a widow who has long survived her husband without a curiosity not easily put into terms. The curiosity is intensified, and the difficulty enhanced if there are children to testify of a relation which, in the absence of the dead, has no other witness. The man has passed out of the woman’s life as absolutely as if he had never been there; it is conceivable that she herself does not always think of her children as also his. Yet they are his children, and there must be times when he holds her in mortmain through them, when he is still her husband, still her lord and master. But how much, otherwise, does she keep of that intimate history of emotions, experiences, so manifold, so recondite? Is he as utterly gone, to her sense, as to all others? Or is he in some sort there still, in her ear, in her eye, in her touch? Was it for the nothing which it now seems that they were associated in the most tremendous of the human dramas, the drama that allies human nature with the creative, the divine and the immortal, on one side, the bestial and the perishable on the other? Does oblivion pass equally over the tremendous and the trivial and blur them alike?

Anther looked at Mrs. Langbrith in a whirl of question: question of himself as well as of her. By virtue of his privity to her past, he was in a sort of authority over her; but it may have been because of his knowledge that he almost humbly forbore to use his authority.

“Amelia,” he entreated her, “have you brought him up in a superstition of his father?”

“Oh no!” She had the effect of hurrying to answer him. “Oh, never!”

“ I am glad of that, anyway. But if you have let him grow up in ignorance—

“How could I help that?”

“You couldn’t! He made himself solid, there. But the boy’s reverence for his father’s memory is sacrilege—”

“I know,” she tremulously consented; and in her admission there was no feint of sparing the dead, of defending the name she bore, or the man whose son she had borne. She must have gone all over that ground long ago, and abandoned it. “ It ought to have come out,” she even added.

“Yes, but it never can come out now, while any of his victims live,” Anther helplessly raged. “ I’m willing to help keep it covered up in his grave myself, because you’re one of them. If poor Hawberk had only taken to drink instead of opium!”

“Yes,” she again consented, with no more apparent feeling for the memory imperiled by the conjecture than if she had been nowise concerned in it.

“But you must, Amelia—I hate to blame you; I know how true you are—you must have let the boy think—”

“As a child, he used to ask me, but not much; and what would you have had I should answer him?”

“ Of course, of course! You couldn’t.”

“ I used to wonder if I could. Once, when he was little, he put his finger on this”—she put her own finger on a scar over her left eye—“and asked me what made it. I almost told him.”

Anther groaned and twisted in his chair. “The child always spoke of him,” she went on passionlessly, “ as being in heaven. I found out, one night, when I was saying his prayers with him, that—you know how children get things mixed up in their thoughts—he supposed Mr. Langbrith was the father in heaven he was praying to.”

“Gracious powers!” Anther broke out.

“I suppose,” she concluded, with a faint sigh, “though it’s no comfort, that there are dark corners in other houses.”

“Plenty,” Anther grimly answered, from the physician’s knowledge. “ But not many as dark as in yours, Amelia.”

“No,” she passively consented once more. “As he grew up,” she resumed the thread of their talk, without prompting, “he seemed less and less curious about it; and I let it go. I suppose I wanted to escape from it, to forget it.”

“I don’t blame you.”

“But, doctor,” she pleaded with him for the extenuation which she could not, perhaps, find in herself, “ I never did teach him by any word or act— unless not saying anything was doing it—that his father was the sort of man he thinks he was. I should have been afraid that Mr. Langbrith himself would not have liked that. It would have been a fraud upon the child.”

‘‘I don’t think Langbrith would have objected to it on that ground,” Anther bitterly suggested.

‘‘No, perhaps not. But between Mr. Langbrith and me there were no concealments, and I felt that he would not have wished me to impose upon the child expressly.”

“ Oh, he preferred the tacit deceit, if it would serve his purpose. I’ll allow that. And in this case, it seems to have done it.”

“Do you mean,” she meekly asked, “that I have deceived James?”

“No,” said Anther, with a blurt of joyless laughter. “But if such a thing were possible, if it were not too sickeningly near some wretched superstition that doesn’t believe in itself, I should say that his father deceived him through you, that he diabolically acted through your love, and did the evil which we have got to face now. Amelia!” he startled her with the resolution expressed in his utterance of her name, “you say the boy will object to my marrying you. Do you object to my telling him?”

“Telling him?”

“Just what his father was!”

“Oh, you mustn’t! It would make him hate you.”

“What difference?”

“I couldn’t let him hate you. I couldn’t bear that. ” The involuntary tears, kept back in the abstracter passages of their talk, filled her eyes again, and trembled above her cheeks.

" If necessary, he has got to know," Anther went on, obdurately.

" I won't give you up on a mere apprehension of his opposition."

" Oh, do give me up !" she implored. " It would be the best way."

" It would be the worst. I have a right to you, and if you care for me, as you say — "

"I do!"

" Then, heaven help us, you have right to me. You have a right to freedom, to peace, to rest, to security ; and you are going to have it. Now, will you let it come to the question without his having the grounds of a fair judgment, or shall we tell him what he ought to know, and then do what we ought to do : marry, and let me look after you as long as I live?"

She hesitated, and then said, with a sort of furtive evasion of the point: "There is something that I ought to tell you. You said that you would despise yourself if you had cared for me in Mr. Langbrith's lifetime." She always spoke of her husband, dead, as she had always addressed him, living, in the tradition of her great juniority, and in a convention of what was once polite form from wives to husbands, not to be dropped in the most solemn, the most intimate, moments.

Anther found nothing grotesque in it, and therefore nothing peculiarly pathetic. "Well?" he asked, impatiently trying for patience.

"Well, I know that I cared for you then. I couldn't help it. Now you despise me, and that ends it."

Anther rubbed his hand over his face; then he said, "I don't believe you, Amelia."

" I did," she persisted.

"Well, then, it was all right. You couldn't have had a wrong thought or feeling, and the theory may go. After all I was applying the principle in my own case, and trying to equal myself with you. If you choose to equal yourself with me by saying this, I must let you; but it makes no difference. You cared for me because I stood your helper when there was no other possible, and that was right. Now, shall we tell Jim, or not?"

She looked desperately round, as if she might escape the question by escaping from the room. As all the doors were shut, she seemed to abandon the notion of flight, and said, with a deep sigh, " I must see him first."

Anther caught up his hat and put it on, and went out without any form of leave-taking. When the outer door had closed upon him, she stole to the window, and, standing back far enough not to be seen, watched him heavily tramping down the brick walk, with its borders of box, to the white gate-posts, each under its elm, budded against a sky threatening rain, and trailing its pendulous spray in the wind. He jounced into his buggy, and drew the reins over his horse, which had been standing unhitched, and drove away. She turned from the window.

III.

Easter came late that year, and the jonquils were there before it, even in the Mid-New England latitude of Saxmills, when James Langbrith brought his friend Falk home with him for the brief vacation. The two fellows had a great time, as they said to each other, among the village girls; and perhaps Langbrith evinced his local superiority more appreciably by his patronage of them than by the colonial nobleness of the family mansion, squarely fronting the main village street, with gardened grounds behind dropping to the river. He did not dispense his patronage in all cases without having his hand somewhat clawed by the recipients, but still he dispensed it; and, though Falk laughed when Langbrith was scratched, still Langbrith felt that he was more than holding his own, and he made up for any defeat he met outside by the unquestioned supremacy he bore within his mother’s house. Her shyness, out of keeping with her age and stature, invited the sovereign command which Langbrith found it impossible to refuse, though he tempered his tyranny with words and shows of affection well calculated to convince his friend of the perfect intelligence which existed between his mother and himself. When he thought of it, he gave her his arm in going out to dinner; and, when he forgot, he tried to make up by pushing her chair under her before she sat down. He was careful at table to have the conversation first pay its respects to some supposed interest of hers, and to return to that if it strayed afterwards, and include her. He conspicuously kissed her every morning when he came down to breakfast, and he kissed her at night when she would have escaped to bed without the rite.

It was Falk’s own fault if he did not conceive from Langbrith’s tenderness the ideal of what a good son should be in all points. But, as the Western growth of a German stock transplanted a generation before, he may not have been qualified to imagine the whole perfection of Langbrith’s behavior from the examples shown him. His social conditions in the past may even have been such that the ceremonial he witnessed did not impress him pleasantly; but, if so, he made no sign of displeasure. He held his peace, and beyond grinning at Langbrith’s shoulders, as he followed him out to the dining-room, he did not go. He seemed to have made up his mind that, without great loss of self-respect, he could suffer himself to be used in illustration of Langbrith’s large-mindedness with other people whom Langbrith wished to impress. At any rate, it had been a choice between spending the Easter holiday at Cambridge, or coming home with Langbrith; and he was not sorry that he had come. He was getting as much good out of the visit as Langbrith.

One night, when Mrs. Langbrith came timidly into the library to tell the two young men that dinner was ready—she had shifted the dinner-hour, at her son’s wish, from one o’clock to seven—Langbrith turned from the shelf where he had been looking into various books with his friend, and said to his mother, in giving her his arm: “ I can’t understand why my father didn’t have a book-plate, unless it was to leave me the pleasure of getting one up in good shape. I want you to design it for me, will you, Falk?” he asked over his shoulder. Without waiting for the answer, he went on, instructively, to his mother: “You know the name was originally Norman.”

“I didn’t know that,” she said, with a gentle self-inculpation.

“Yes,” her son explained. “I’ve been looking it up. It was Longuehaleine, and they translated it after they came to England into Longbreath, or Langbrith, as we have it. I believe I prefer our final form. It’s splendidly suggestive for a bookplate, don’t you think, Falk?” By this time he was pushing his mother’s chair under her, and talking over her head to his friend. “A boat, with a full sail, and a cherub’s head blowing a strong gale into it: something like that.”

“ They might think the name was Longboat, then,” said Falk.

Mrs. Langbrith started.

“ Oh, Falk has to have his joke,” her son explained, tolerantly, as he took his place; “nobody minds Falk. Mother, I wish you would give a dinner for him. Why not? And we could have a dance afterwards. The old parlors would lend themselves to it handsomely. What do you say, Falk?”

“ Is it for me to say I will be your honored guest?”

“Well, we’ll drop that part. We won’t feature you, if you prefer not. Honestly, though, I’ve been thinking of a dinner, mother.”

Langbrith had now taken his place, and was poising the carving knife and fork over the roast turkey, which symbolized in his mother’s simple tradition the extreme of formal hospitality. She wore her purple silk in honor of it, and it was what chiefly sustained her in the presence of the young men’s evening dress. This was too much for her, perhaps, but not too much for the turkey. The notion of the proposed dinner, however, was something, as she conceived it, beyond the turkey’s support. Without knowing just what her son meant, she cloudily imagined the dinner of his suggestion to be a banquet quite unprecedented in Saxmills society. Dinners there, except in a very few houses, were family dinners, year out and year in. They were sometimes extended to include outlying kindred, cousins and aunts and uncles who chanced to be in town or came on a visit. Very rarely, a dinner was made for some distinguished stranger: a speaker, who was going to address a political rally in the afternoon, or a lecturer, who was to be heard in the evening at the town-hall, or the clerical supply in the person of one minister or another who came to be tried for the vacant pulpit of one of the churches. Then, a few principal citizens with their wives were asked, the ministers of the other churches, the bank president, some leading merchant, the magnates of the law or medicine. The dinner was at one o’clock, and the young people were rigidly excluded. They were fed either before or after it, or farmed out among the _ neighboring houses till the guests were gone. Ordinarily, guests were asked to tea, which was high, with stewed chicken, hot bread, made dishes and several kinds of preserves and sweet pickles, with many sorts of cake. The last was the criterion of tasteful and lavish hospitality.

Clearly, it was nothing of all this that Mrs. Langbrith’s son had in mind. After his first year in college, when he had been so homesick that everything seemed perfect under his mother s roof in his vacation visits, he began to bring fellows with him. Then he began to make changes. The dinner-hour was advanced from mid-day to evening, and he and his friends dressed for it. He had still to carve, for the dinner in courses was really unmanageable and unimaginable in his mother’s housekeeping, but he professed a baronial preference for carving, and he fancied an old-fashioned, old-family effect from it. The service was such as the frightened inexperience of the elderly Irish second-girl could render; under Langbrith’s threatening eye, she succeeded in offering the dishes at the left hand, and, though she stood a good way off and rather pushed them at the guests, the thing somehow was done. At least, the covered dishes were no longer set on the table, as they used always to be.

Mrs. Langbrith had witnessed the changes with trepidation but absolute acquiescence even at the first, and finally with the submission in which her son held her in everything. In the afternoon, when he and his friend, whoever it might be, put on their top-hats and top-coats and went out to call on the village girls, who did not know enough of the world to offer them tea, she spent the interval before dinner in arranging for the meal with the faithful, faded Norah. After dinner, when the young men again put on their top-hats and top-coats to call again upon the village girls, whom they had impressed with the correctness of afternoon calls, and to whom they now relented in compliance with the village custom of evening calls, Mrs. Langbrith debated with Norah the success of the dinner, studied its errors, and joined her in vows for their avoidance.

IV

The event which confronted Mrs. Langbrith in her son’s words, as he sat behind the turkey and plunged the carving fork into its steaming and streaming breast, was so far beyond the scope of her widened knowledge that she mutely waited for him to declare it.

“ People,” he went on, “ have been so nice to Falk and me, that I think we ought to make some return. I put the duty side first, because I know you’ll like that, mother, and it will help to reconcile you to the fun of it. Falk is such a pagan that he can’t understand, but it will be for his good, all the same. My notion is to have a good, big dinner—twelve or fourteen at table, and then a lot in afterwards, with supper about midnight. What do you say, mother? Don’t mind Falk, if you don’t agree quite.”

“There is no Falk, Mrs. Langbrith,” the young fellow said, with an intelligence which comforted her and emboldened her against her son.

“I don’t see—she began, and then she stopped.

“That’s right!” her son encouraged her.

“James,” she said, desperately, “I wouldn’t know how to do it.”

“I don’t want you to do it.” He laughed exultantly. “ I propose to do it myself. I will have the whole thing sent up from Boston.” Between her gasps, he went on: “All I have got to do is to write an order to White, the caterer, with particulars of quantity and quality, the date and the hour, and it comes on the appointed train with three men in plain clothes; two reappear in lustrous dress-suits at dinner and supper, and serve the things the other has cooked at our range. I press the button, White does the rest. He brings china, cutlery, linen— everything. All you have to do is to hide Jerry in the barn and keep Norah up-stairs to show the ladies into the back chamber to take off their things. You can put our own cook under the sink. You’ll be astonished at the ease of the whole thing.”

“ Yes,” Mrs. Langbrith said, “it will be easy, but—”

“ But would it be right?” her son tenderly mocked. “ What did I tell you?” he asked towards his friend. “In New England, the notion of ease conveys the sense of culpability. My mother is afraid she would have a bad conscience. If she took all the work and worry on herself, she would feel that she was paying the penalty of her pleasure beforehand; if she didn’t, she would know that she must pay for it afterwards. Isn’t that so, mother? But now you leave it to me, you dear old thing.” Langbrith ran round the table and kissed her on top of the head, and made her blush like a girl, as he patted her shoulder. “Just imagine I was master, and you couldn’t help yourself.” He went back to his place. “ What was the largest dinner you ever had in the old time?”

She hesitated, as if for his meaning. “ Mr. Langbrith once entertained a company of six gentlemen, who came up here and talked of locating some cotton-mills. We called it “ supper.’ ”

“I can imagine them. Can’t you, Falk? The moneyed man to supply the funds, the lawyer to draw up the papers, the civil engineer to survey the property. Very solemn, and a little pompous, but secretly ready for a burst if the opportunity offered under the right auspices; something like an outing of city officials.”

“They were very pleasant gentlemen,” Mrs. Langbrith interposed, as from her conscience.

“Oh, I dare say they were when they had tasted my father’s madeira. But about our dinner now? I don’t think we’d better have more than twelve, and I should want them equally divided between youth and age.”

Mrs. Langbrith looked at him as if she did not quite understand him, and he said:

“Have Jessamy Colebridge and Hope Hawberk and Susie Johns and Bob Matthewson—he’s a good fellow—and make out the half-dozen with Falk and me; we’re both good fellows. Then, on your side of the line, yourself first of all, mother, and the rector and his wife, and Judge and Mrs. Garley, and—who else? Oh, Dr. Anther, of course! I want Falk to meet the doctor—the dearest and quaintest old type in the world. I don’t know why he hasn’t been in to see us, mother. Has he been here lately?”

“He was here a day or two before you came,” Mrs. Langbrith answered, with her eyes down.

“Perhaps he has been waiting for me to call. Well, what do you think of my dinner-party?’’

“It seems very nice,’’ Mrs. Langbrith sighed.

“And haven’t you any preferences? Nobody you want to turn down?”

“ It will be a good deal of a surprise for Saxmills,” she suffered herself to say.

“I flatter myself it will. I have been telling Falk that the mixed assembly of old and young is unknown in Saxmills.”

Falk had not troubled himself to take part in the discussion, if it was that, but had given himself to the turkey and the cranberry sauce, with the mashed potatoes and the stewed squash, which Mrs. Langbrith had very good. Her son had obliged her to provide claret, which Falk now drank out of an abnormal glass with a stout stem and pimpled cup, hitherto dedicated to currant wine, before saying: “ It astonished me less than if I had been used to something different all my life. You ought to have tried the other thing on me.”

“Well, I only supposed from the smartness of the people in your Caricature pictures that you had always lived in a whirl of fashion.”

“That shows how little you know of fashion,” said Falk, and Langbrith laughed with the difficult joy of a man who owns a hit.

Mrs. Langbrith glanced from one to the other; from her son, with his long, distinguished face (he had decided that it was colonial), to the dark, aquiline type of Falk, with his black hair, his upward-pointed mustache, his pouted lips, and his prominent, floating, brown eyes. In her abeyance, she was scared at the bold person who was not afraid of her son.

“Well,” said Langbrith, “I shall have to find someone to illustrate my vers de society who knows enough of the world for both.”

“You couldn’t!” Falk insinuated.

Mrs. Langbrith did not quite catch the point, but her son laughed again. “No one ever distances you, Falk!”

He discussed the arrangement of the affair with his mother. At the end, as she rose, obedient to his sign, and he came round to give her his arm, he said: “After all, perhaps, it wouldn’t be well to strike too hard a blow. If you think you can get it up by Saturday night, mother, we’ll drop the notion of having White. Make it tea, with turkey at one end of the table and chicken pie at the other, and all the sweet pickles and preserves and kinds of cake you can get together; coffee straight through, and a glass of the old Langbrith madeira to top off with.”

V

Mrs. Langbrith went into the library with her son and his friend by the folding doors from the dining-room, but only to go out of the door which opened into the hall, and escape by that route to the kitchen for an immediate conference with the cook.

The young men dropped into deep leather chairs at opposite corners of the fireplace, after lighting their cigars. Probably, the comfort of his seat suggested Langbrith’s reflection: “ It is a shame I never knew my father. We should have had so much in common. I couldn’t imagine anything more adapted to the human back than these chairs.”

“His taste?” Falk asked, between whiffs.

“Everything in the house is his taste. I don’t believe my mother has changed a thing. He must have been a strong personality.” Langbrith followed his friend’s eye in its lift towards his father’s portrait over the mantel.

“I should think so,” Falk assented.

“Those old New England faces,” Langbrith continued, meditatively, “have a great charm. From a child, that face of my father’s fascinated me. As I got on, and began to be interested in my environment, I read into it all I had read out of Hawthorne about the Puritan type. I put the grim old chaps out of The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables and the Twice-Told Tales into it, and interpreted my father by them. But, really, I knew very little about him. My mother’s bereavement seemed to have sealed her lips, and I preferred dreaming to asking. A kid is queer! Once or twice when I did ask, she evaded answering; that was after I was old enough to understand, and I didn’t press my questions. He was much older than she; twenty years, I believe. He couldn’t have been a Puritan in his creed; he was a Unitarian, as far as churchgoing went, and I believe my mother is a Unitarian yet; but she goes to the Episcopal Church, which makes itself a home for everybody, and she likes the rector. You’ll like him, too, Falk.”

“He won’t talk theology to me, I suppose,” Falk grumbled.

“He’ll talk athletics with you. The good thing about a man of his church is that he’s usually a man of the world, too. He’s an Enderby, you know.”

“I shouldn’t be much the wiser, if I did,” Falk said.

“I wouldn’t work that pose so hard, Falk. You can’t get even with the Enderbys by ignoring them; and you can’t pretend it’s meekness that makes you profess ignorance. The only thing I don’t like about you is your peasant pride.”

“I still have hopes of winning your whole heart then. I’ll study your peasant humility.”

Langbrith made as if he had not noticed the point. He rose and moved restively about the room, and then came back to his chair again, and said, as if he had really been thinking of something else: “If I should decide to take up dramatic literature, I believe I’ll go to Paris to continue my studies, and perhaps we’ll keep on there together. I wish we could! Can’t you manage it, somehow? Those things of yours in Caricature have attracted attention; and if Life has asked you to send something, why couldn’t you get a lot of orders, and go out with me?”

“Gentle dreamer!” Falk murmured.

“No, but why not, really?”

“ Because a lot of orders are not to be got for the asking, and I’m a bad hand at asking. I think my cheek is good for applying to a New York paper for a chance to do scenes in court, and hurry-pictures of fires, and the persons in a vivid accident; but I don’t think it would hold out to invite Harper's or Scribner's to have me do high-class studies abroad for them. I may be a fool, but I am not that kind of fool. Unless,” Falk hastened to anticipate, “I’m all kinds.”

Langbrith was apparently not watching for the chance snatched from him. “Well, I think you could do it, somehow,” he insisted. “I’m going to Paris for my post-graduate business, and I’ve set my heart on having you with me. I wonder,” he mused aloud, “why I like you so much, Falk?”

“I couldn’t say,” Falk returned, without apparent interest in the mystery.

“You’re always saying nasty things to me,” Langbrith pursued. “You take every chance to give me a dig.”

“It’s all that keeps you in bounds.”

“No—”

“Yes, it is; your arrogance would naturally splay all over the place. But just at present, you’re in the melting mood that saps everybody’s manhood towards the end of the senior year. If I didn’t watch myself, I should feel a tenderness for you at times.”

“Would you, really, Falk?” Langbrith appeared touched, and interested.

“ I shall never know, for I don’t mean to be taken off my guard.”

“What a delightful fellow you are, Falk!”

“Do you think so? I should suppose you were a woman.”

“Oh, it isn’t the women alone that love you, old man. I love you because you are the only one who is frank with me.”

“It takes courage to be candid with a prince. But, thank Heaven, I have it.”

“ Oh, pshaw! There’s nobody by to admire your sarcasms.”

“I’m satisfied with you, my dear boy.”

“Will you answer me a serious question seriously?”

“Yes, if you keep your hands off, and don’t try to pat me on the head.”

Langbrith was silent, and he would not speak, in his resentment, till Falk said, “Fire away.”

Still it was an interval before Langbrith recovered poise enough to ask, “What do you think of Jessamy Colebridge?”

“Hope Hawberk, you mean,” Falk promptly translated.

Langbrith laughed, and said, “Well, make it Hope Hawberk.”

“She’s about the prettiest girl I’ve seen.”

“Isn’t she! And the gracefulest. There’s more charm in grace than in beauty, every time.”

“There is, this time, it seems.”

Langbrith laughed again for pleasure. “She has grace of mind. I don’t know where she gets it. Her father—well, that’s a tragedy.”

“ Better tell it.”

“ It would take a long time to do it justice. He was my father’s partner, here, when the mills were started, and I’ve heard he was a very brilliant fellow. They were great friends. But he must have had some sort of dry rot, always, and he took to opium.”

“Kill him?”

“No, it doesn’t kill on those terms, I believe. He’s away just now on one of his periodical retreats in a sanatorium, where they profess to cure opium-eating. There’s a lot of it among the country people about here—the women, especially. When Hawberk comes out, he is fitter than ever for opium.”

“Well, that’s something.”

“I suppose it’s Dr. Anther that keeps him along. I want you to meet Dr. Anther, Falk.”

“ I inferred as much from a remark you made at dinner.”

“Oh, I believe I did speak of it. Well, now you know I mean it. He’s one of those men—doctors or lawyers, mostly; you don’t catch the reverend clergy hiding their light under a bushel quite so much—who could have been something great in the larger world, if they hadn’t preferred a small world. I suppose it is a streak of indolence in them. Anther’s practice has kept him poor in Saxmills, but it would have made him rich in Boston. You mustn’t imagine that he’s been rusting scientifically here. He is thoroughly up to. date as a physician; goes away now and then and rubs up in New York. He’s been our family physician ever since I can remember, and before. My father and he were great cronies, I believe, though he’s never boasted of it. I have inferred it from things my mother has dropped; or perhaps,” Langbrith laughed, “I’ve only imagined it. At any rate, he dates back to my father’s time, and two strong men, both willing to stay in Saxmills, must have had a good deal in common. He’s always been in and out of the house, more like a friend than a physician. A guardian couldn’t have looked after me better, when it was a question of advice; and, as a doctor, he pulled me through all the ills that flesh of kids is heir to. He has that abrupt quaintness that an old doctor gets. He would go into a play or a book just as he is. You don’t care so much for that sort of man as I do, I know, for you’re a sort of character yourself. Now, I’m different. I—”

“This seems getting to be more about you than your doctor,” Falk said. He rose, threw the end of his cigar into the fire, and stretched himself.

What is the matter with our going to see some of those girls?”

Langbrith flushed, as he rose too, but he said nothing in making for the door with his friend.

They met his mother before they reached the door, on her return from the kitchen. She gave the conscious start which every encounter with her son surprised from her since his home-coming, and gasped, Will you—shall you—see the young people, James? Or shall I?”

I can save you that trouble, mother. Falk and I were just going out to make some calls, and we can ask the girls.”

“ Well,” his mother said, and she passed the young men on her way into the room, while they stood aside for her; she gave her housekeeping glance over it, to see what things would have to be put in place when they were gone. “Then, I will ask the others, and we will have the dance after supper. Were you going,” she turned to her son with, for the first time, something like interest, “to ask Hope?”

“Why, certainly!”

“Yes. That was what I understood.”

“Didn’t you want me to?—I mentioned her.”

“Yes, yes, oh yes. I forgot. And your uncle John?”

“Yes, certainly. But you know he won’t come. Wild horses couldn’t get him here.”

“You ought to ask him.”

“Now, that’s just like my mother,” Langbrith said, as he went out with Falk into the night. “ Uncle John has had charge of the mills here ever since my father died, and he was nominally my guardian. But he hasn’t been inside of the house, I believe, half a dozen times, except on business, and he barely knows me by sight.”

“ The one I met yesterday in the office?”

‘‘Yes. That’s where he lives; that’s his home; though, of course, he has a place where he sleeps and eats, and has an old colored man to keep house for him. He’s a perfect hermit, and he’ll only hate a little less to be asked to come than he would to come. But mother wouldn’t omit asking him on any account. It makes me laugh.”

VI

The young men walked away under the windy April sky, with the boughs of the elms that overhung the village street creaking in the starless dark. The smell of spring was in the air, which beat damply and refreshingly in their faces, hot from the indoors warmth.

Langbrith was the first to speak again; but he did not speak till he had opened the gate of the walk leading up to the door of the house where he decided to begin their rounds. “Hello! they’re at home, apparently,” he said.

The windows of the house before them, as they showed to their advance through the leafless spray of the shrubbery, were bright with lamplight, and the sound of a piano, broken in upon with gay shouts and shrieks of girls’ laughter, penetrated the doors and the casements. If there had been any doubt on the point made, it was dispersed at their ring. There came a nervous whoop from within, followed by whispering and tittering; and then the door was flung open by Jessamy Colebridge herself, obscured by the light which silhouetted her little head and jump figure to the young men on the threshold.

“Why, Mr. Langbrith! And Mr. Falk! Well, if this isn’t too much! We were just talking— weren’t we, girls?” she called over her shoulder into the room she had left, and Langbrith asked gravely.

“May we come in? If you are at home?

“At home! I should think so! Papa and mamma are at evening meeting, and I let the two girls go; and I have got in Hope and Susie here to cheer me up, for I’m down sick, if you want to know, with the most fearful cold. I only hope it isn’t grippe, but you can’t tell.”

She led them, chattering, into the parlor, where the other young ladies, stricken with sudden decorum, stood like statues of themselves in the attitude of joyous alarm which the ring at the door had surprised them into.

One of them, a slender girl, with masses of black hair, imperfectly put away from her face, which looked reddened beyond the tint natural to her type, flared at the young men with large black eyes, in a sort of defiant question. The other, short and dense of figure, was a decided blonde; her smooth hair was a pale gold, and her serenely smiling face, with its close-drawn eyelids—the lower almost touching the upper, and wrinkling the fine short nose—was what is called “funny.” It was flushed, too, but was of a delicacy of complexion duly attested by its freckles.

There was a strong smell of burning in the room, and, somehow, an effect of things having been scurried out of sight.

The slim girl gave a wild cry, and precipitated herself towards the fireplace as if plunging into it; but it was only to snatch from the bed of coals a long-handled wire cage, from the meshes of which a thick, acrid smoke was pouring. “Much good it did to hustle the plates away and leave this burning up! Open the window, Jessamy!”

But Jessamy left Langbrith to do it, while she clapped her hands and stood shouting: “We were popping corn! The furnace fire was out, and I lit this to keep the damp out, and we thought we would pop some com! There was such a splendid bed of coals, and I was playing, and Susie and Hope were popping the com! We were in such a gale, and we all hustled the things away when you rang, for we didn’t know who you were, and the girls thought it would be too absurd to be caught popping corn, and in the hurry we forgot all about the popper itself, and left it burning up full of corn!”

Her voice rose to a screech, and she bowed herself with laughter, while she beat her hands together.

The young men listened according to their nature. Falk said: “I thought it was the house burning down. I didn’t know which of you ladies wanted to be saved first.”

The girl who had ran to throw the corn-popper out of the window came back with Langbrith, who shut the window behind her. “Oh, I can swim,” she said, and they all laughed at her joke.

“ Well, then, get the corn, Hope,” Jessamy shrieked; “we may as well be hung for a sheep as a goat. It is a goat, isn’t it?” she appealed to the young men.

“ It doesn’t seem as if it were,” Langbrith answered, with mock thoughtfulness.

“Some of those animals, then,” the girl laughed over her shoulder. “Where did I put the plates, Susie?”

“ I know where I put the corn,” Hope said, going to the portiere, where it touched the floor next the room beyond.

Falk ran after her. “Let me help carry it,” he entreated.

“Do get the salt, Susie,” Jessamy commanded. “ I know where the plates are now."

“ We hadn’t got to the salt,” Susie Johns said; but Jessamy had not heard her when she stooped over the music-rack and handed up three plates to Langbrith.

Falk came with Hope, elaborately supporting one handle of the dish with a little heap of popped corn in the bottom. She held the other and explained, “ We had only got to the first popping,” and Jessamy added:

“We were not expecting company.”

“We could go away,” Langbrith suggested.

“ Susie, have you got the salt?” Jessamy implored, putting the plates on the piano. Susie stood smiling serenely, and again the hostess forgot her. “ Shall we have it on the piano, girls? Oh, I know; let’s have it on the hearth-rug here.”

“Yes,” Langbrith said, doubling his lankness down before the fire. He went on:

“ ‘ For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground,

And tell sad stories of the deaths of kings.’ ”

Jessamy had not minded the hoyden prank in which he took her at her word, but the name he seemed to invoke so lightly shocked her. She drew her face down and looked grave.

“It isn’t swearing, Jessamy,” Hope Hawberk reassured her; “it’s only Shakespeare. Mr. Langbrith never talks anything but Shakespeare, you know.” She had a deep, throaty voice, which gave weight to her irony.

“Oh, all right,” said Jessamy. “Susie, you wicked thing, have you got that salt? Why, of course! I never brought it from the dining-room. Here, sit by Mr. Langbrith, as Hope calls him—his Christian name used to be Jim—and keep him from Shakespearing, while I go for it.”

“You might get him a plate, too,” Falk called after her. Susie coiled herself softly, kitten-like, down on the rug at Langbrith’s side. “I’m going to eat out of the dish.”

“Hope, don’t you let him!” Jessamy screamed on her way to the dining-room.

When she came back, she distributed the plates among her guests, and with one, in which Hope had put her a portion of corn, she stood behind them. “Bless you, my children,” she said. “Now, trot out your kings, Jimmy—Mr. Langbrith, I should say.”

“Oh no,” Langbrith protested; “ghosts. We oughtn’t to tell anything less goose-fleshing than ghost-stories before this fire.”

“Why, I thought you said your kings were dead. Good kings, dead kings!” Jessamy added, with no relation of ideas. “Or is it Indians?”

Anything served. They were young, and alone —joyful mysteries to themselves and to one another. They talked and laughed. They hardly knew what they said, and not at all why they laughed.

At nine o’clock, Jessamy’s father and mother came home, and with them someone whose voice they knew. The elders discreetly went up-stairs, when Jessamy called out to whoever it was had come with them, “Come in here, Harry Matthewson.”

They received him with gay screams, Jessamy having dropped to her knees beside the others, for the greater effect upon the smiling young fellow who came in rubbing his hands.

“Well, well!’’ he said.

“ Now this is a little too pat,” Langbrith protested, and he gave the invitation which he had come with, and which met with no dissent.

“ It is a vote,” said Matthewson, with the authority of a young lawyer beginning to take part in town meetings.

“Well, now,” Langbrith said, getting to his feet, “the business of the meeting being over, I move Falk and I adjourn.”

“No, no, don’t let him, Mr. Falk! You don’t want to go, do you?”

“Only for a breath of air. I’m nearly roasted.”

Matthewson laughed. “ I wondered what you were sitting round the fire for; it’s as mild as May out, and there’s a full moon.”

“A full moon?” Jessamy put out her hand for him to help her up. The other girls put out their hands for help, too. “Then I’ll tell you what. We’ll go home with the poor things, and see that the goblins don’t get them. What do you say, girls?”

"Oh! they say ‘yes.’ Don’t you, girls?” Langbrith entreated, with clasped hand.

The young men helped them put on their wraps. Jessamy, when she was fully equipped for the adventure, called up-stairs to her mother: “Mamma, I am going out for a few minutes.” Her mother shrieked back: “Jessamy Colebridge, don’t you do it. You’ll take your death.”

“No, I won’t, mamma. The air will do my cold good,” and she closed the debate by shutting the door behind her. “Now, that’s settled,” she said. “Where shall we go first?”

The notion of going home with Langbrith and Falk seemed to be relinquished. They went about from one house to another, where there were girls of their acquaintance, and sang before their gates or under their windows. At the first sign of consciousness within, they fled with shrieks and shouts.

In the assortment of couples, Matthewson led the way with Susie Johns, Falk followed with Jessamy, Langbrith and Hope were paired. Sometimes, the girls ran on alone; sometimes, in the dark places, they took the young men’s arms.

They saw each other to their houses; then, not to be outdone in civility, the girls who were left came away with those who had left them. It promised never to end, and no one seemed to care. The joy of their youth had gone to their heads in a divine madness, in which differences of temperament were merged and they were all alike.

Langbrith did not know how it happened that he was at last taking leave of Hope Hawberk alone at her gate. He stooped over to whisper something. She pulled her hand from his arm, and said, “ Don’t be silly!” and ran up the walk to her door. The elastic weight of her hand remained on his arm.

VII

The compromise between a Boston dinner and a Saxmills tea, which the mother and son had agreed upon, prospered beyond the wont of compromises. It was a very good meal of the older-fashioned sort, and it was better served by Norah, from her habit of such meals, than could have been expected, with the help of the niece she had got in for the evening. The turkey was set before Langbrith and the chicken pie before his mother. Norah asked the guests which they would have, in taking their plates, and brought the plates back with the chosen portion, and the vegetables added by the host or hostess from the deep dishes on their right and left. There were small plates of subsidiary viands, such as brandied peaches and sweet pickles, which the guests passed to one another. Tea and coffee and cocoa were served through the supper by Norah’s niece from the pantry, where she had them hot from the kitchen stove. There was no wine till the ladies left the table, when Langbrith had Norah put down, with the cigars, some decanters of madeira from, as he said, his father’s stock. He had a little pomp in saying that; it seemed to him there was something ancestral in it.