0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: David De Angelis

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Often revealingly autobiographical, DuBois explores topics as diverse as the death of his infant son and the politics of Booker T. Washington. In every essay, he shows the consequences of both a political color line and an internal one, as he grapples with the contradictions of being black and being American. One of our country's most influential books, The Souls of Black Folk reflects the mind of a visionary who inspired generations of readers to remember the past, question the status quo, and fight for a just tomorrow.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

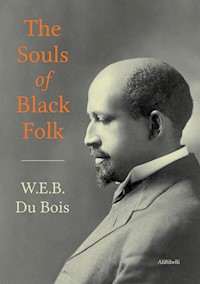

The Souls of Black Folk

by W. E. B. Du Bois

Edition 2018 by David De Angelis - all rights reserved

Table of Contents

The Forethought

I Of Our Spiritual Strivings

II Of the Dawn of Freedom

III Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others

IV Of the Meaning of Progress

V Of the Wings of Atalanta

VI Of the Training of Black Men

VII Of the Black Belt

VIII Of the Quest of the Golden Fleece

IX Of the Sons of Master and Man

X Of the Faith of the Fathers

XI Of the Passing of the First-Born

XII Of Alexander Crummell

XIII Of the Coming of John

XIV Of the Sorrow Songs

The Afterthought

The Forethought

Herein lie buried many things which if read with patience mayshow the strange meaning of being black here at the dawning of theTwentieth Century. This meaning is not without interest to you,Gentle Reader; for the problem of the Twentieth Century is theproblem of the color line. I pray you, then, receive my little bookin all charity, studying my words with me, forgiving mistake andfoible for sake of the faith and passion that is in me, and seekingthe grain of truth hidden there.

I have sought here to sketch, in vague, uncertain outline, thespiritual world in which ten thousand thousand Americans live andstrive. First, in two chapters I have tried to show whatEmancipation meant to them, and what was its aftermath. In a thirdchapter I have pointed out the slow rise of personal leadership,and criticized candidly the leader who bears the chief burden ofhis race to-day. Then, in two other chapters I have sketched inswift outline the two worlds within and without the Veil, and thushave come to the central problem of training men for life.Venturing now into deeper detail, I have in two chapters studiedthe struggles of the massed millions of the black peasantry, and inanother have sought to make clear the present relations of the sonsof master and man. Leaving, then, the white world, I have steppedwithin the Veil, raising it that you may view faintly its deeperrecesses,—the meaning of its religion, the passion of itshuman sorrow, and the struggle of its greater souls. All this Ihave ended with a tale twice told but seldom written, and a chapterof song.

Some of these thoughts of mine have seen the light before inother guise. For kindly consenting to their republication here, inaltered and extended form, I must thank the publishers of theAtlantic Monthly, The World's Work, the Dial, The New World, andthe Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.Before each chapter, as now printed, stands a bar of the SorrowSongs,—some echo of haunting melody from the only Americanmusic which welled up from black souls in the dark past. And,finally, need I add that I who speak here am bone of the bone andflesh of the flesh of them that live within the Veil?

W.E.B Du B. ATLANTA, GA., FEB. 1, 1903.

Of Our Spiritual Strivings

O water, voice of my heart, crying in the sand, All night longcrying with a mournful cry, As I lie and listen, and cannotunderstand The voice of my heart in my side or the voice of thesea, O water, crying for rest, is it I, is it I? All night long thewater is crying to me.

Unresting water, there shall never be rest Till the last moondroop and the last tide fail, And the fire of the end begin to burnin the west; And the heart shall be weary and wonder and cry likethe sea, All life long crying without avail, As the water all nightlong is crying to me. ARTHUR SYMONS.

Between me and the other world there is ever an unaskedquestion: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by othersthrough the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless,flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way,eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of sayingdirectly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know anexcellent colored man in my town; or, I fought at Mechanicsville;or, Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil? At these Ismile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as theoccasion may require. To the real question, How does it feel to bea problem? I answer seldom a word.

And yet, being a problem is a strange experience,—peculiareven for one who has never been anything else, save perhaps inbabyhood and in Europe. It is in the early days of rollickingboyhood that the revelation first bursts upon one, all in a day, asit were. I remember well when the shadow swept across me. I was alittle thing, away up in the hills of New England, where the darkHousatonic winds between Hoosac and Taghkanic to the sea. In a weewooden schoolhouse, something put it into the boys' and girls'heads to buy gorgeous visiting-cards—ten cents apackage—and exchange. The exchange was merry, till one girl,a tall newcomer, refused my card,—refused it peremptorily,with a glance. Then it dawned upon me with a certain suddennessthat I was different from the others; or like, mayhap, in heart andlife and longing, but shut out from their world by a vast veil. Ihad thereafter no desire to tear down that veil, to creep through;I held all beyond it in common contempt, and lived above it in aregion of blue sky and great wandering shadows. That sky was bluestwhen I could beat my mates at examination-time, or beat them at afoot-race, or even beat their stringy heads. Alas, with the yearsall this fine contempt began to fade; for the words I longed for,and all their dazzling opportunities, were theirs, not mine. Butthey should not keep these prizes, I said; some, all, I would wrestfrom them. Just how I would do it I could never decide: by readinglaw, by healing the sick, by telling the wonderful tales that swamin my head,—some way. With other black boys the strife wasnot so fiercely sunny: their youth shrunk into tastelesssycophancy, or into silent hatred of the pale world about them andmocking distrust of everything white; or wasted itself in a bittercry, Why did God make me an outcast and a stranger in mine ownhouse? The shades of the prison-house closed round about us all:walls strait and stubborn to the whitest, but relentlessly narrow,tall, and unscalable to sons of night who must plod darkly on inresignation, or beat unavailing palms against the stone, orsteadily, half hopelessly, watch the streak of blue above.

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teutonand Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with aveil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—aworld which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only letshim see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is apeculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of alwayslooking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuringone's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contemptand pity. One ever feels his twoness,—an American, a Negro;two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warringideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it frombeing torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of thisstrife,—this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, tomerge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merginghe wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He would notAfricanize America, for America has too much to teach the world andAfrica. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of whiteAmericanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for theworld. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both aNegro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by hisfellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly inhis face.

This, then, is the end of his striving: to be a co-worker in thekingdom of culture, to escape both death and isolation, to husbandand use his best powers and his latent genius. These powers of bodyand mind have in the past been strangely wasted, dispersed, orforgotten. The shadow of a mighty Negro past flits through the taleof Ethiopia the Shadowy and of Egypt the Sphinx. Through history,the powers of single black men flash here and there like fallingstars, and die sometimes before the world has rightly gauged theirbrightness. Here in America, in the few days since Emancipation,the black man's turning hither and thither in hesitant and doubtfulstriving has often made his very strength to lose effectiveness, toseem like absence of power, like weakness. And yet it is notweakness,—it is the contradiction of double aims. Thedouble-aimed struggle of the black artisan—on the one hand toescape white contempt for a nation of mere hewers of wood anddrawers of water, and on the other hand to plough and nail and digfor a poverty-stricken horde—could only result in making hima poor craftsman, for he had but half a heart in either cause. Bythe poverty and ignorance of his people, the Negro minister ordoctor was tempted toward quackery and demagogy; and by thecriticism of the other world, toward ideals that made him ashamedof his lowly tasks. The would-be black savant was confronted by theparadox that the knowledge his people needed was a twice-told taleto his white neighbors, while the knowledge which would teach thewhite world was Greek to his own flesh and blood. The innate loveof harmony and beauty that set the ruder souls of his peoplea-dancing and a-singing raised but confusion and doubt in the soulof the black artist; for the beauty revealed to him was thesoul-beauty of a race which his larger audience despised, and hecould not articulate the message of another people. This waste ofdouble aims, this seeking to satisfy two unreconciled ideals, haswrought sad havoc with the courage and faith and deeds of tenthousand thousand people,—has sent them often wooing falsegods and invoking false means of salvation, and at times has evenseemed about to make them ashamed of themselves.

Away back in the days of bondage they thought to see in onedivine event the end of all doubt and disappointment; few men everworshipped Freedom with half such unquestioning faith as did theAmerican Negro for two centuries. To him, so far as he thought anddreamed, slavery was indeed the sum of all villainies, the cause ofall sorrow, the root of all prejudice; Emancipation was the key toa promised land of sweeter beauty than ever stretched before theeyes of wearied Israelites. In song and exhortation swelled onerefrain—Liberty; in his tears and curses the God he imploredhad Freedom in his right hand. At last it came,—suddenly,fearfully, like a dream. With one wild carnival of blood andpassion came the message in his own plaintive cadences:—

"Shout, O children! Shout, you're free! For God has bought yourliberty!"

Years have passed away since then,—ten, twenty, forty;forty years of national life, forty years of renewal anddevelopment, and yet the swarthy spectre sits in its accustomedseat at the Nation's feast. In vain do we cry to this our vastestsocial problem:—

"Take any shape but that, and my firm nerves Shall nevertremble!"

The Nation has not yet found peace from its sins; the freedmanhas not yet found in freedom his promised land. Whatever of goodmay have come in these years of change, the shadow of a deepdisappointment rests upon the Negro people,—a disappointmentall the more bitter because the unattained ideal was unbounded saveby the simple ignorance of a lowly people.

The first decade was merely a prolongation of the vain searchfor freedom, the boon that seemed ever barely to elude theirgrasp,—like a tantalizing will-o'-the-wisp, maddening andmisleading the headless host. The holocaust of war, the terrors ofthe Ku-Klux Klan, the lies of carpet-baggers, the disorganizationof industry, and the contradictory advice of friends and foes, leftthe bewildered serf with no new watchword beyond the old cry forfreedom. As the time flew, however, he began to grasp a new idea.The ideal of liberty demanded for its attainment powerful means,and these the Fifteenth Amendment gave him. The ballot, whichbefore he had looked upon as a visible sign of freedom, he nowregarded as the chief means of gaining and perfecting the libertywith which war had partially endowed him. And why not? Had notvotes made war and emancipated millions? Had not votes enfranchisedthe freedmen? Was anything impossible to a power that had done allthis? A million black men started with renewed zeal to votethemselves into the kingdom. So the decade flew away, therevolution of 1876 came, and left the half-free serf weary,wondering, but still inspired. Slowly but steadily, in thefollowing years, a new vision began gradually to replace the dreamof political power,—a powerful movement, the rise of anotherideal to guide the unguided, another pillar of fire by night aftera clouded day. It was the ideal of "book-learning"; the curiosity,born of compulsory ignorance, to know and test the power of thecabalistic letters of the white man, the longing to know. Here atlast seemed to have been discovered the mountain path to Canaan;longer than the highway of Emancipation and law, steep and rugged,but straight, leading to heights high enough to overlook life.

Up the new path the advance guard toiled, slowly, heavily,doggedly; only those who have watched and guided the falteringfeet, the misty minds, the dull understandings, of the dark pupilsof these schools know how faithfully, how piteously, this peoplestrove to learn. It was weary work. The cold statistician wrotedown the inches of progress here and there, noted also where hereand there a foot had slipped or some one had fallen. To the tiredclimbers, the horizon was ever dark, the mists were often cold, theCanaan was always dim and far away. If, however, the vistasdisclosed as yet no goal, no resting-place, little but flattery andcriticism, the journey at least gave leisure for reflection andself-examination; it changed the child of Emancipation to the youthwith dawning self-consciousness, self-realization, self-respect. Inthose sombre forests of his striving his own soul rose before him,and he saw himself,—darkly as through a veil; and yet he sawin himself some faint revelation of his power, of his mission. Hebegan to have a dim feeling that, to attain his place in the world,he must be himself, and not another. For the first time he soughtto analyze the burden he bore upon his back, that dead-weight ofsocial degradation partially masked behind a half-named Negroproblem. He felt his poverty; without a cent, without a home,without land, tools, or savings, he had entered into competitionwith rich, landed, skilled neighbors. To be a poor man is hard, butto be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom ofhardships. He felt the weight of his ignorance,—not simply ofletters, but of life, of business, of the humanities; theaccumulated sloth and shirking and awkwardness of decades andcenturies shackled his hands and feet. Nor was his burden allpoverty and ignorance. The red stain of bastardy, which twocenturies of systematic legal defilement of Negro women had stampedupon his race, meant not only the loss of ancient African chastity,but also the hereditary weight of a mass of corruption from whiteadulterers, threatening almost the obliteration of the Negrohome.

A people thus handicapped ought not to be asked to race with theworld, but rather allowed to give all its time and thought to itsown social problems. But alas! while sociologists gleefully counthis bastards and his prostitutes, the very soul of the toiling,sweating black man is darkened by the shadow of a vast despair. Mencall the shadow prejudice, and learnedly explain it as the naturaldefence of culture against barbarism, learning against ignorance,purity against crime, the "higher" against the "lower" races. Towhich the Negro cries Amen! and swears that to so much of thisstrange prejudice as is founded on just homage to civilization,culture, righteousness, and progress, he humbly bows and meeklydoes obeisance. But before that nameless prejudice that leapsbeyond all this he stands helpless, dismayed, and well-nighspeechless; before that personal disrespect and mockery, theridicule and systematic humiliation, the distortion of fact andwanton license of fancy, the cynical ignoring of the better and theboisterous welcoming of the worse, the all-pervading desire toinculcate disdain for everything black, from Toussaint to thedevil,—before this there rises a sickening despair that woulddisarm and discourage any nation save that black host to whom"discouragement" is an unwritten word.

But the facing of so vast a prejudice could not but bring theinevitable self-questioning, self-disparagement, and lowering ofideals which ever accompany repression and breed in an atmosphereof contempt and hate. Whisperings and portents came home upon thefour winds: Lo! we are diseased and dying, cried the dark hosts; wecannot write, our voting is vain; what need of education, since wemust always cook and serve? And the Nation echoed and enforced thisself-criticism, saying: Be content to be servants, and nothingmore; what need of higher culture for half-men? Away with the blackman's ballot, by force or fraud,—and behold the suicide of arace! Nevertheless, out of the evil came something ofgood,—the more careful adjustment of education to real life,the clearer perception of the Negroes' social responsibilities, andthe sobering realization of the meaning of progress.

So dawned the time of Sturm und Drang: storm and stress to-dayrocks our little boat on the mad waters of the world-sea; there iswithin and without the sound of conflict, the burning of body andrending of soul; inspiration strives with doubt, and faith withvain questionings. The bright ideals of the past,—physicalfreedom, political power, the training of brains and the trainingof hands,—all these in turn have waxed and waned, until eventhe last grows dim and overcast. Are they all wrong,—allfalse? No, not that, but each alone was over-simple andincomplete,—the dreams of a credulous race-childhood, or thefond imaginings of the other world which does not know and does notwant to know our power. To be really true, all these ideals must bemelted and welded into one. The training of the schools we needto-day more than ever,—the training of deft hands, quick eyesand ears, and above all the broader, deeper, higher culture ofgifted minds and pure hearts. The power of the ballot we need insheer self-defence,—else what shall save us from a secondslavery? Freedom, too, the long-sought, we still seek,—thefreedom of life and limb, the freedom to work and think, thefreedom to love and aspire. Work, culture, liberty,—all thesewe need, not singly but together, not successively but together,each growing and aiding each, and all striving toward that vasterideal that swims before the Negro people, the ideal of humanbrotherhood, gained through the unifying ideal of Race; the idealof fostering and developing the traits and talents of the Negro,not in opposition to or contempt for other races, but rather inlarge conformity to the greater ideals of the American Republic, inorder that some day on American soil two world-races may give eachto each those characteristics both so sadly lack. We the darkerones come even now not altogether empty-handed: there are to-day notruer exponents of the pure human spirit of the Declaration ofIndependence than the American Negroes; there is no true Americanmusic but the wild sweet melodies of the Negro slave; the Americanfairy tales and folklore are Indian and African; and, all in all,we black men seem the sole oasis of simple faith and reverence in adusty desert of dollars and smartness. Will America be poorer ifshe replace her brutal dyspeptic blundering with light-hearted butdetermined Negro humility? or her coarse and cruel wit with lovingjovial good-humor? or her vulgar music with the soul of the SorrowSongs?

Merely a concrete test of the underlying principles of the greatrepublic is the Negro Problem, and the spiritual striving of thefreedmen's sons is the travail of souls whose burden is almostbeyond the measure of their strength, but who bear it in the nameof an historic race, in the name of this the land of their fathers'fathers, and in the name of human opportunity.

And now what I have briefly sketched in large outline let me oncoming pages tell again in many ways, with loving emphasis anddeeper detail, that men may listen to the striving in the souls ofblack folk.

Of the Dawn of Freedom

Careless seems the great Avenger; History's lessons but recordOne death-grapple in the darkness 'Twixt old systems and the Word;Truth forever on the scaffold, Wrong forever on the throne; Yetthat scaffold sways the future, And behind the dim unknown StandethGod within the shadow Keeping watch above His own. LOWELL.

The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of thecolor-line,—the relation of the darker to the lighter racesof men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.It was a phase of this problem that caused the Civil War; andhowever much they who marched South and North in 1861 may havefixed on the technical points, of union and local autonomy as ashibboleth, all nevertheless knew, as we know, that the question ofNegro slavery was the real cause of the conflict. Curious it was,too, how this deeper question ever forced itself to the surfacedespite effort and disclaimer. No sooner had Northern armiestouched Southern soil than this old question, newly guised, sprangfrom the earth,—What shall be done with Negroes? Peremptorymilitary commands this way and that, could not answer the query;the Emancipation Proclamation seemed but to broaden and intensifythe difficulties; and the War Amendments made the Negro problems ofto-day.

It is the aim of this essay to study the period of history from1861 to 1872 so far as it relates to the American Negro. In effect,this tale of the dawn of Freedom is an account of that governmentof men called the Freedmen's Bureau,—one of the most singularand interesting of the attempts made by a great nation to grapplewith vast problems of race and social condition.

The war has naught to do with slaves, cried Congress, thePresident, and the Nation; and yet no sooner had the armies, Eastand West, penetrated Virginia and Tennessee than fugitive slavesappeared within their lines. They came at night, when theflickering camp-fires shone like vast unsteady stars along theblack horizon: old men and thin, with gray and tufted hair; womenwith frightened eyes, dragging whimpering hungry children; men andgirls, stalwart and gaunt,—a horde of starving vagabonds,homeless, helpless, and pitiable, in their dark distress. Twomethods of treating these newcomers seemed equally logical toopposite sorts of minds. Ben Butler, in Virginia, quickly declaredslave property contraband of war, and put the fugitives to work;while Fremont, in Missouri, declared the slaves free under martiallaw. Butler's action was approved, but Fremont's was hastilycountermanded, and his successor, Halleck, saw things differently."Hereafter," he commanded, "no slaves should be allowed to comeinto your lines at all; if any come without your knowledge, whenowners call for them deliver them." Such a policy was difficult toenforce; some of the black refugees declared themselves freemen,others showed that their masters had deserted them, and stillothers were captured with forts and plantations. Evidently, too,slaves were a source of strength to the Confederacy, and were beingused as laborers and producers. "They constitute a militaryresource," wrote Secretary Cameron, late in 1861; "and being such,that they should not be turned over to the enemy is too plain todiscuss." So gradually the tone of the army chiefs changed;Congress forbade the rendition of fugitives, and Butler's"contrabands" were welcomed as military laborers. This complicatedrather than solved the problem, for now the scattering fugitivesbecame a steady stream, which flowed faster as the armiesmarched.

Then the long-headed man with care-chiselled face who sat in theWhite House saw the inevitable, and emancipated the slaves ofrebels on New Year's, 1863. A month later Congress called earnestlyfor the Negro soldiers whom the act of July, 1862, had halfgrudgingly allowed to enlist. Thus the barriers were levelled andthe deed was done. The stream of fugitives swelled to a flood, andanxious army officers kept inquiring: "What must be done withslaves, arriving almost daily? Are we to find food and shelter forwomen and children?"

It was a Pierce of Boston who pointed out the way, and thusbecame in a sense the founder of the Freedmen's Bureau. He was afirm friend of Secretary Chase; and when, in 1861, the care ofslaves and abandoned lands devolved upon the Treasury officials,Pierce was specially detailed from the ranks to study theconditions. First, he cared for the refugees at Fortress Monroe;and then, after Sherman had captured Hilton Head, Pierce was sentthere to found his Port Royal experiment of making free workingmenout of slaves. Before his experiment was barely started, however,the problem of the fugitives had assumed such proportions that itwas taken from the hands of the over-burdened Treasury Departmentand given to the army officials. Already centres of massed freedmenwere forming at Fortress Monroe, Washington, New Orleans, Vicksburgand Corinth, Columbus, Ky., and Cairo, Ill., as well as at PortRoyal. Army chaplains found here new and fruitful fields;"superintendents of contrabands" multiplied, and some attempt atsystematic work was made by enlisting the able-bodied men andgiving work to the others.

Then came the Freedmen's Aid societies, born of the touchingappeals from Pierce and from these other centres of distress. Therewas the American Missionary Association, sprung from the Amistad,and now full-grown for work; the various church organizations, theNational Freedmen's Relief Association, the American Freedmen'sUnion, the Western Freedmen's Aid Commission,—in all fifty ormore active organizations, which sent clothes, money, school-books,and teachers southward. All they did was needed, for thedestitution of the freedmen was often reported as "too appallingfor belief," and the situation was daily growing worse rather thanbetter.

And daily, too, it seemed more plain that this was no ordinarymatter of temporary relief, but a national crisis; for here loomeda labor problem of vast dimensions. Masses of Negroes stood idle,or, if they worked spasmodically, were never sure of pay; and ifperchance they received pay, squandered the new thingthoughtlessly. In these and other ways were camp-life and the newliberty demoralizing the freedmen. The broader economicorganization thus clearly demanded sprang up here and there asaccident and local conditions determined. Here it was that Pierce'sPort Royal plan of leased plantations and guided workmen pointedout the rough way. In Washington the military governor, at theurgent appeal of the superintendent, opened confiscated estates tothe cultivation of the fugitives, and there in the shadow of thedome gathered black farm villages. General Dix gave over estates tothe freedmen of Fortress Monroe, and so on, South and West. Thegovernment and benevolent societies furnished the means ofcultivation, and the Negro turned again slowly to work. The systemsof control, thus started, rapidly grew, here and there, intostrange little governments, like that of General Banks inLouisiana, with its ninety thousand black subjects, its fiftythousand guided laborers, and its annual budget of one hundredthousand dollars and more. It made out four thousand pay-rolls ayear, registered all freedmen, inquired into grievances andredressed them, laid and collected taxes, and established a systemof public schools. So, too, Colonel Eaton, the superintendent ofTennessee and Arkansas, ruled over one hundred thousand freedmen,leased and cultivated seven thousand acres of cotton land, and fedten thousand paupers a year. In South Carolina was General Saxton,with his deep interest in black folk. He succeeded Pierce and theTreasury officials, and sold forfeited estates, leased abandonedplantations, encouraged schools, and received from Sherman, afterthat terribly picturesque march to the sea, thousands of thewretched camp followers.

Three characteristic things one might have seen in Sherman'sraid through Georgia, which threw the new situation in shadowyrelief: the Conqueror, the Conquered, and the Negro. Some see allsignificance in the grim front of the destroyer, and some in thebitter sufferers of the Lost Cause. But to me neither soldier norfugitive speaks with so deep a meaning as that dark human cloudthat clung like remorse on the rear of those swift columns,swelling at times to half their size, almost engulfing and chokingthem. In vain were they ordered back, in vain were bridges hewnfrom beneath their feet; on they trudged and writhed and surged,until they rolled into Savannah, a starved and naked horde of tensof thousands. There too came the characteristic military remedy:"The islands from Charleston south, the abandoned rice-fields alongthe rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the countrybordering the St. John's River, Florida, are reserved and set apartfor the settlement of Negroes now made free by act of war." So readthe celebrated "Field-order Number Fifteen."

All these experiments, orders, and systems were bound to attractand perplex the government and the nation. Directly after theEmancipation Proclamation, Representative Eliot had introduced abill creating a Bureau of Emancipation; but it was never reported.The following June a committee of inquiry, appointed by theSecretary of War, reported in favor of a temporary bureau for the"improvement, protection, and employment of refugee freedmen," onmuch the same lines as were afterwards followed. Petitions came into President Lincoln from distinguished citizens and organizations,strongly urging a comprehensive and unified plan of dealing withthe freedmen, under a bureau which should be "charged with thestudy of plans and execution of measures for easily guiding, and inevery way judiciously and humanely aiding, the passage of ouremancipated and yet to be emancipated blacks from the old conditionof forced labor to their new state of voluntary industry."

Some half-hearted steps were taken to accomplish this, in part,by putting the whole matter again in charge of the special Treasuryagents. Laws of 1863 and 1864 directed them to take charge of andlease abandoned lands for periods not exceeding twelve months, andto "provide in such leases, or otherwise, for the employment andgeneral welfare" of the freedmen. Most of the army officers greetedthis as a welcome relief from perplexing "Negro affairs," andSecretary Fessenden, July 29, 1864, issued an excellent system ofregulations, which were afterward closely followed by GeneralHoward. Under Treasury agents, large quantities of land were leasedin the Mississippi Valley, and many Negroes were employed; but inAugust, 1864, the new regulations were suspended for reasons of"public policy," and the army was again in control.