Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: e-artnow

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

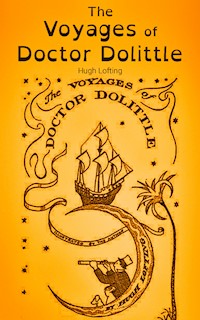

When Tommy Stubbins finds a squirrel injured by a hawk, Matthew Mugg, the cat's meat man, informs him to get help from Doctor Dolittle, who can speak the language of animals. The Doctor is away on a voyage, but when he returns, he attends to the squirrel. Tommy is introduced to some of the strange animals in Doolittle's care, and begins his studies with Doolittle, or rather with Polynesia who teaches Tommy the language of animals.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 367

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle

Table of Contents

THE POPSIPETEL PICTURE-HISTORY OF KING JONG THINKALOT

Prologue

All that I have written so far about Doctor Dolittle I heard long after it happened from those who had known him—indeed a great deal of it took place before I was born. But I now come to set down that part of the great man’s life which I myself saw and took part in.

Many years ago the Doctor gave me permission to do this. But we were both of us so busy then voyaging around the world, having adventures and filling note-books full of natural history that I never seemed to get time to sit down and write of our doings.

Now of course, when I am quite an old man, my memory isn’t so good any more. But whenever I am in doubt and have to hesitate and think, I always ask Polynesia, the parrot.

That wonderful bird (she is now nearly two hundred and fifty years old) sits on the top of my desk, usually humming sailor songs to herself, while I write this book. And, as every one who ever met her knows, Polynesia’s memory is the most marvelous memory in the world. If there is any happening I am not quite sure of, she is always able to put me right, to tell me exactly how it took place, who was there and everything about it. In fact sometimes I almost think I ought to say that this book was written by Polynesia instead of me.

Very well then, I will begin. And first of all I must tell you something about myself and how I came to meet the Doctor.

PART ONE

The First Chapter The Cobbler’s Son

My name was Tommy Stubbins, son of Jacob Stubbins, the cobbler of Puddleby-on-the-Marsh; and I was nine and a half years old. At that time Puddleby was only quite a small town. A river ran through the middle of it; and over this river there was a very old stone bridge, called Kingsbridge, which led you from the market-place on one side to the churchyard on the other.

Sailing-ships came up this river from the sea and anchored near the bridge. I used to go down and watch the sailors unloading the ships upon the river-wall. The sailors sang strange songs as they pulled upon the ropes; and I learned these songs by heart. And I would sit on the river-wall with my feet dangling over the water and sing with the men, pretending to myself that I too was a sailor.

For I longed always to sail away with those brave ships when they turned their backs on Puddleby Church and went creeping down the river again, across the wide lonely marshes to the sea. I longed to go with them out into the world to seek my fortune in foreign lands—Africa, India, China and Peru! When they got round the bend in the river and the water was hidden from view, you could still see their huge brown sails towering over the roofs of the town, moving onward slowly—like some gentle giants that walked among the houses without noise. What strange things would they have seen, I wondered, when next they came back to anchor at Kingsbridge! And, dreaming of the lands I had never seen, I’d sit on there, watching till they were out of sight.

Three great friends I had in Puddleby in those days. One was Joe, the mussel-man, who lived in a tiny hut by the edge of the water under the bridge. This old man was simply marvelous at making things. I never saw a man so clever with his hands. He used to mend my toy ships for me which I sailed upon the river; he built windmills out of packing-cases and barrel-staves; and he could make the most wonderful kites from old umbrellas.

Joe would sometimes take me in his mussel-boat, and when the tide was running out we would paddle down the river as far as the edge of the sea to get mussels and lobsters to sell. And out there on the cold lonely marshes we would see wild geese flying, and curlews and redshanks and many other kinds of seabirds that live among the samfire and the long grass of the great salt fen. And as we crept up the river in the evening, when the tide had turned, we would see the lights on Kingsbridge twinkle in the dusk, reminding us of tea-time and warm fires.

Another friend I had was Matthew Mugg, the cat’s-meat-man. He was a funny old person with a bad squint. He looked rather awful but he was really quite nice to talk to. He knew everybody in Puddleby; and he knew all the dogs and all the cats. In those times being a cat’s-meat-man was a regular business. And you could see one nearly any day going through the streets with a wooden tray full of pieces of meat stuck on skewers crying, “Meat! M-E-A-T!” People paid him to give this meat to their cats and dogs instead of feeding them on dog-biscuits or the scraps from the table.

I enjoyed going round with old Matthew and seeing the cats and dogs come running to the garden-gates whenever they heard his call. Sometimes he let me give the meat to the animals myself; and I thought this was great fun. He knew a lot about dogs and he would tell me the names of the different kinds as we went through the town. He had several dogs of his own; one, a whippet, was a very fast runner, and Matthew used to win prizes with her at the Saturday coursing races; another, a terrier, was a fine ratter. The cat’s-meat-man used to make a business of rat-catching for the millers and farmers as well as his other trade of selling cat’s-meat.

My third great friend was Luke the Hermit. But of him I will tell you more later on.

I did not go to school; because my father was not rich enough to send me. But I was extremely fond of animals. So I used to spend my time collecting birds’ eggs and butterflies, fishing in the river, rambling through the countryside after blackberries and mushrooms and helping the mussel-man mend his nets.

Yes, it was a very pleasant life I lived in those days long ago—though of course I did not think so then. I was nine and a half years old; and, like all boys, I wanted to grow up—not knowing how well off I was with no cares and nothing to worry me. Always I longed for the time when I should be allowed to leave my father’s house, to take passage in one of those brave ships, to sail down the river through the misty marshes to the sea—out into the world to seek my fortune.

The Second Chapter I Hear of the Great Naturalist

One early morning in the Springtime, when I was wandering among the hills at the back of the town, I happened to come upon a hawk with a squirrel in its claws. It was standing on a rock and the squirrel was fighting very hard for its life. The hawk was so frightened when I came upon it suddenly like this, that it dropped the poor creature and flew away. I picked the squirrel up and found that two of its legs were badly hurt. So I carried it in my arms back to the town.

When I came to the bridge I went into the mussel-man’s hut and asked him if he could do anything for it. Joe put on his spectacles and examined it carefully. Then he shook his head.

“Yon crittur’s got a broken leg,” he said—“and another badly cut an’ all. I can mend you your boats, Tom, but I haven’t the tools nor the learning to make a broken squirrel seaworthy. This is a job for a surgeon—and for a right smart one an’ all. There be only one man I know who could save yon crittur’s life. And that’s John Dolittle.”

“Who is John Dolittle?” I asked. “Is he a vet?”

“No,” said the mussel-man. “He’s no vet. Doctor Dolittle is a nacheralist.”

“What’s a nacheralist?”

“A nacheralist,” said Joe, putting away his glasses and starting to fill his pipe, “is a man who knows all about animals and butterflies and plants and rocks an’ all. John Dolittle is a very great nacheralist. I’m surprised you never heard of him—and you daft over animals. He knows a whole lot about shellfish—that I know from my own knowledge. He’s a quiet man and don’t talk much; but there’s folks who do say he’s the greatest nacheralist in the world.”

“Where does he live?” I asked.

“Over on the Oxenthorpe Road, t’other side the town. Don’t know just which house it is, but ’most anyone ’cross there could tell you, I reckon. Go and see him. He’s a great man.”

So I thanked the mussel-man, took up my squirrel again and started off towards the Oxenthorpe Road.

The first thing I heard as I came into the market-place was some one calling “Meat! M-E-A-T!”

“There’s Matthew Mugg,” I said to myself. “He’ll know where this Doctor lives. Matthew knows everyone.”

So I hurried across the market-place and caught him up.

“Matthew,” I said, “do you know Doctor Dolittle?”

“Do I know John Dolittle!” said he. “Well, I should think I do! I know him as well as I know my own wife—better, I sometimes think. He’s a great man—a very great man.”

“Can you show me where he lives?” I asked. “I want to take this squirrel to him. It has a broken leg.”

“Certainly,” said the cat’s-meat-man. “I’ll be going right by his house directly. Come along and I’ll show you.”

So off we went together.

“Oh, I’ve known John Dolittle for years and years,” said Matthew as we made our way out of the market-place. “But I’m pretty sure he ain’t home just now. He’s away on a voyage. But he’s liable to be back any day. I’ll show you his house and then you’ll know where to find him.”

All the way down the Oxenthorpe Road Matthew hardly stopped talking about his great friend, Doctor John Dolittle—“M. D.” He talked so much that he forgot all about calling out “Meat!” until we both suddenly noticed that we had a whole procession of dogs following us patiently.

“Where did the Doctor go to on this voyage?” I asked as Matthew handed round the meat to them.

“I couldn’t tell you,” he answered. “Nobody never knows where he goes, nor when he’s going, nor when he’s coming back. He lives all alone except for his pets. He’s made some great voyages and some wonderful discoveries. Last time he came back he told me he’d found a tribe of Red Indians in the Pacific Ocean—lived on two islands, they did. The husbands lived on one island and the wives lived on the other. Sensible people, some of them savages. They only met once a year, when the husbands came over to visit the wives for a great feast—Christmas-time, most likely. Yes, he’s a wonderful man is the Doctor. And as for animals, well, there ain’t no one knows as much about ’em as what he does.”

“How did he get to know so much about animals?” I asked.

The cat’s-meat-man stopped and leant down to whisper in my ear.

“He talks their language,” he said in a hoarse, mysterious voice.

“The animals’ language?” I cried.

“Why certainly,” said Matthew. “All animals have some kind of a language. Some sorts talk more than others; some only speak in sign-language, like deaf-and-dumb. But the Doctor, he understands them all—birds as well as animals. We keep it a secret though, him and me, because folks only laugh at you when you speak of it. Why, he can even write animal-language. He reads aloud to his pets. He’s wrote history-books in monkey-talk, poetry in canary language and comic songs for magpies to sing. It’s a fact. He’s now busy learning the language of the shellfish. But he says it’s hard work—and he has caught some terrible colds, holding his head under water so much. He’s a great man.”

“He certainly must be,” I said. “I do wish he were home so I could meet him.”

“Well, there’s his house, look,” said the cat’s-meat-man—“that little one at the bend in the road there—the one high up—like it was sitting on the wall above the street.”

We were now come beyond the edge of the town. And the house that Matthew pointed out was quite a small one standing by itself. There seemed to be a big garden around it; and this garden was much higher than the road, so you had to go up a flight of steps in the wall before you reached the front gate at the top. I could see that there were many fine fruit trees in the garden, for their branches hung down over the wall in places. But the wall was so high I could not see anything else.

When we reached the house Matthew went up the steps to the front gate and I followed him. I thought he was going to go into the garden; but the gate was locked. A dog came running down from the house; and he took several pieces of meat which the cat’s-meat-man pushed through the bars of the gate, and some paper bags full of corn and bran. I noticed that this dog did not stop to eat the meat, as any ordinary dog would have done, but he took all the things back to the house and disappeared. He had a curious wide collar round his neck which looked as though it were made of brass or something. Then we came away.

“The Doctor isn’t back yet,” said Matthew, “or the gate wouldn’t be locked.”

“What were all those things in paper-bags you gave the dog?” I asked.

“Oh, those were provisions,” said Matthew—“things for the animals to eat. The Doctor’s house is simply full of pets. I give the things to the dog, while the Doctor’s away, and the dog gives them to the other animals.”

“And what was that curious collar he was wearing round his neck?”

“That’s a solid gold dog-collar,” said Matthew. “It was given to him when he was with the Doctor on one of his voyages long ago. He saved a man’s life.”

“How long has the Doctor had him?” I asked.

“Oh, a long time. Jip’s getting pretty old now. That’s why the Doctor doesn’t take him on his voyages any more. He leaves him behind to take care of the house. Every Monday and Thursday I bring the food to the gate here and give it him through the bars. He never lets any one come inside the garden while the Doctor’s away—not even me, though he knows me well. But you’ll always be able to tell if the Doctor’s back or not—because if he is, the gate will surely be open.”

So I went off home to my father’s house and put my squirrel to bed in an old wooden box full of straw. And there I nursed him myself and took care of him as best I could till the time should come when the Doctor would return. And every day I went to the little house with the big garden on the edge of the town and tried the gate to see if it were locked. Sometimes the dog, Jip, would come down to the gate to meet me. But though he always wagged his tail and seemed glad to see me, he never let me come inside the garden.

The Third Chapter The Doctor’s Home

One Monday afternoon towards the end of April my father asked me to take some shoes which he had mended to a house on the other side of the town. They were for a Colonel Bellowes who was very particular.

I found the house and rang the bell at the front door. The Colonel opened it, stuck out a very red face and said, “Go round to the tradesmen’s entrance—go to the back door.” Then he slammed the door shut.

I felt inclined to throw the shoes into the middle of his flower-bed. But I thought my father might be angry, so I didn’t. I went round to the back door, and there the Colonel’s wife met me and took the shoes from me. She looked a timid little woman and had her hands all over flour as though she were making bread. She seemed to be terribly afraid of her husband whom I could still hear stumping round the house somewhere, grunting indignantly because I had come to the front door. Then she asked me in a whisper if I would have a bun and a glass of milk. And I said, “Yes, please.”

After I had eaten the bun and milk, I thanked the Colonel’s wife and came away. Then I thought that before I went home I would go and see if the Doctor had come back yet. I had been to his house once already that morning. But I thought I’d just like to go and take another look. My squirrel wasn’t getting any better and I was beginning to be worried about him.

So I turned into the Oxenthorpe Road and started off towards the Doctor’s house. On the way I noticed that the sky was clouding over and that it looked as though it might rain.

I reached the gate and found it still locked. I felt very discouraged. I had been coming here every day for a week now. The dog, Jip, came to the gate and wagged his tail as usual, and then sat down and watched me closely to see that I didn’t get in.

I began to fear that my squirrel would die before the Doctor came back. I turned away sadly, went down the steps on to the road and turned towards home again.

I wondered if it were supper-time yet. Of course I had no watch of my own, but I noticed a gentleman coming towards me down the road; and when he got nearer I saw it was the Colonel out for a walk. He was all wrapped up in smart overcoats and mufflers and bright-colored gloves. It was not a very cold day but he had so many clothes on he looked like a pillow inside a roll of blankets. I asked him if he would please tell me the time.

He stopped, grunted and glared down at me—his red face growing redder still; and when he spoke it sounded like the cork coming out of a gingerbeer-bottle.

“Do you imagine for one moment,” he spluttered, “that I am going to get myself all unbuttoned just to tell a little boy like you the time!” And he went stumping down the street, grunting harder than ever.

I stood still a moment looking after him and wondering how old I would have to be, to have him go to the trouble of getting his watch out. And then, all of a sudden, the rain came down in torrents.

I have never seen it rain so hard. It got dark, almost like night. The wind began to blow; the thunder rolled; the lightning flashed, and in a moment the gutters of the road were flowing like a river. There was no place handy to take shelter, so I put my head down against the driving wind and started to run towards home.

I hadn’t gone very far when my head bumped into something soft and I sat down suddenly on the pavement. I looked up to see whom I had run into. And there in front of me, sitting on the wet pavement like myself, was a little round man with a very kind face. He wore a shabby high hat and in his hand he had a small black bag.

“I’m very sorry,” I said. “I had my head down and I didn’t see you coming.”

To my great surprise, instead of getting angry at being knocked down, the little man began to laugh.

“You know this reminds me,” he said, “of a time once when I was in India. I ran full tilt into a woman in a thunderstorm. But she was carrying a pitcher of molasses on her head and I had treacle in my hair for weeks afterwards—the flies followed me everywhere. I didn’t hurt you, did I?”

“No,” I said. “I’m all right.”

“It was just as much my fault as it was yours, you know,” said the little man. “I had my head down too—but look here, we mustn’t sit talking like this. You must be soaked. I know I am. How far have you got to go?”

“My home is on the other side of the town,” I said, as we picked ourselves up.

“My Goodness, but that was a wet pavement!” said he. “And I declare it’s coming down worse than ever. Come along to my house and get dried. A storm like this can’t last.”

He took hold of my hand and we started running back down the road together. As we ran I began to wonder who this funny little man could be, and where he lived. I was a perfect stranger to him, and yet he was taking me to his own home to get dried. Such a change, after the old red-faced Colonel who had refused even to tell me the time! Presently we stopped.

“Here we are,” he said.

I looked up to see where we were and found myself back at the foot of the steps leading to the little house with the big garden! My new friend was already running up the steps and opening the gate with some keys he took from his pocket.

“Surely,” I thought, “this cannot be the great Doctor Dolittle himself!”

I suppose after hearing so much about him I had expected some one very tall and strong and marvelous. It was hard to believe that this funny little man with the kind smiling face could be really he. Yet here he was, sure enough, running up the steps and opening the very gate which I had been watching for so many days!

The dog, Jip, came rushing out and started jumping up on him and barking with happiness. The rain was splashing down heavier than ever.

“Are you Doctor Dolittle?” I shouted as we sped up the short garden-path to the house.

“Yes, I’m Doctor Dolittle,” said he, opening the front door with the same bunch of keys. “Get in! Don’t bother about wiping your feet. Never mind the mud. Take it in with you. Get in out of the rain!”

I popped in, he and Jip following. Then he slammed the door to behind us.

The storm had made it dark enough outside; but inside the house, with the door closed, it was as black as night. Then began the most extraordinary noise that I have ever heard. It sounded like all sorts and kinds of animals and birds calling and squeaking and screeching at the same time. I could hear things trundling down the stairs and hurrying along passages. Somewhere in the dark a duck was quacking, a cock was crowing, a dove was cooing, an owl was hooting, a lamb was bleating and Jip was barking. I felt birds’ wings fluttering and fanning near my face. Things kept bumping into my legs and nearly upsetting me. The whole front hall seemed to be filling up with animals. The noise, together with the roaring of the rain, was tremendous; and I was beginning to grow a little bit scared when I felt the Doctor take hold of my arm and shout into my ear.

“Don’t be alarmed. Don’t be frightened. These are just some of my pets. I’ve been away three months and they are glad to see me home again. Stand still where you are till I strike a light. My Gracious, what a storm!—Just listen to that thunder!”

So there I stood in the pitch-black dark, while all kinds of animals which I couldn’t see chattered and jostled around me. It was a curious and a funny feeling. I had often wondered, when I had looked in from the front gate, what Doctor Dolittle would be like and what the funny little house would have inside it. But I never imagined it would be anything like this. Yet somehow after I had felt the Doctor’s hand upon my arm I was not frightened, only confused. It all seemed like some queer dream; and I was beginning to wonder if I was really awake, when I heard the Doctor speaking again:

“My blessed matches are all wet. They won’t strike. Have you got any?”

“No, I’m afraid I haven’t,” I called back.

“Never mind,” said he. “Perhaps Dab-Dab can raise us a light somewhere.”

Then the Doctor made some funny clicking noises with his tongue and I heard some one trundle up the stairs again and start moving about in the rooms above.

Then we waited quite a while without anything happening.

“Will the light be long in coming?” I asked. “Some animal is sitting on my foot and my toes are going to sleep.”

“No, only a minute,” said the Doctor. “She’ll be back in a minute.”

And just then I saw the first glimmerings of a light around the landing above. At once all the animals kept quiet.

“I thought you lived alone,” I said to the Doctor.

“So I do,” said he. “It is Dab-Dab who is bringing the light.”

I looked up the stairs trying to make out who was coming. I could not see around the landing but I heard the most curious footstep on the upper flight. It sounded like some one hopping down from one step to the other, as though he were using only one leg.

As the light came lower, it grew brighter and began to throw strange jumping shadows on the walls.

“Ah—at last!” said the Doctor. “Good old Dab-Dab!”

And then I thought I really must be dreaming. For there, craning her neck round the bend of the landing, hopping down the stairs on one leg, came a spotless white duck. And in her right foot she carried a lighted candle!

The Fourth Chapter The Wiff-Waff

When at last I could look around me I found that the hall was indeed simply full of animals. It seemed to me that almost every kind of creature from the countryside must be there: a pigeon, a white rat, an owl, a badger, a jackdaw—there was even a small pig, just in from the rainy garden, carefully wiping his feet on the mat while the light from the candle glistened on his wet pink back.

The Doctor took the candlestick from the duck and turned to me.

“Look here,” he said: “you must get those wet clothes off—by the way, what is your name?”

“Tommy Stubbins,” I said.

“Oh, are you the son of Jacob Stubbins, the shoemaker?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Excellent bootmaker, your father,” said the Doctor. “You see these?” and he held up his right foot to show me the enormous boots he was wearing. “Your father made me those boots four years ago, and I’ve been wearing them ever since—perfectly wonderful boots—Well now, look here, Stubbins. You’ve got to change those wet things—and quick. Wait a moment till I get some more candles lit, and then we’ll go upstairs and find some dry clothes. You’ll have to wear an old suit of mine till we can get yours dry again by the kitchen-fire.”

So presently when more candles had been lighted round different parts of the house, we went upstairs; and when we had come into a bedroom the Doctor opened a big wardrobe and took out two suits of old clothes. These we put on. Then we carried our wet ones down to the kitchen and started a fire in the big chimney. The coat of the Doctor’s which I was wearing was so large for me that I kept treading on my own coat-tails while I was helping to fetch the wood up from the cellar. But very soon we had a huge big fire blazing up the chimney and we hung our wet clothes around on chairs.

“Now let’s cook some supper,” said the Doctor.—“You’ll stay and have supper with me, Stubbins, of course?”

Already I was beginning to be very fond of this funny little man who called me “Stubbins,” instead of “Tommy” or “little lad” (I did so hate to be called “little lad”!) This man seemed to begin right away treating me as though I were a grown-up friend of his. And when he asked me to stop and have supper with him I felt terribly proud and happy. But I suddenly remembered that I had not told my mother that I would be out late. So very sadly I answered,

“Thank you very much. I would like to stay, but I am afraid that my mother will begin to worry and wonder where I am if I don’t get back.”

“Oh, but my dear Stubbins,” said the Doctor, throwing another log of wood on the fire, “your clothes aren’t dry yet. You’ll have to wait for them, won’t you? By the time they are ready to put on we will have supper cooked and eaten—Did you see where I put my bag?”

“I think it is still in the hall,” I said. “I’ll go and see.”

I found the bag near the front door. It was made of black leather and looked very, very old. One of its latches was broken and it was tied up round the middle with a piece of string.

“Thank you,” said the Doctor when I brought it to him.

“Was that bag all the luggage you had for your voyage?” I asked.

“Yes,” said the Doctor, as he undid the piece of string. “I don’t believe in a lot of baggage. It’s such a nuisance. Life’s too short to fuss with it. And it isn’t really necessary, you know—Where did I put those sausages?”

The Doctor was feeling about inside the bag. First he brought out a loaf of new bread. Next came a glass jar with a curious metal top to it. He held this up to the light very carefully before he set it down upon the table; and I could see that there was some strange little water-creature swimming about inside. At last the Doctor brought out a pound of sausages.

“Now,” he said, “all we want is a frying-pan.”

We went into the scullery and there we found some pots and pans hanging against the wall. The Doctor took down the frying-pan. It was quite rusty on the inside.

“Dear me, just look at that!” said he. “That’s the worst of being away so long. The animals are very good and keep the house wonderfully clean as far as they can. Dab-Dab is a perfect marvel as a housekeeper. But some things of course they can’t manage. Never mind, we’ll soon clean it up. You’ll find some silver-sand down there, under the sink, Stubbins. Just hand it up to me, will you?”

In a few moments we had the pan all shiny and bright and the sausages were put over the kitchen-fire and a beautiful frying smell went all through the house.

While the Doctor was busy at the cooking I went and took another look at the funny little creature swimming about in the glass jar.

“What is this animal?” I asked.

“Oh that,” said the Doctor, turning round—“that’s a Wiff-Waff. Its full name is hippocampus pippitopitus. But the natives just call it a Wiff-Waff—on account of the way it waves its tail, swimming, I imagine. That’s what I went on this last voyage for, to get that. You see I’m very busy just now trying to learn the language of the shellfish. They have languages, of that I feel sure. I can talk a little shark language and porpoise dialect myself. But what I particularly want to learn now is shellfish.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Well, you see, some of the shellfish are the oldest kind of animals in the world that we know of. We find their shells in the rocks—turned to stone—thousands of years old. So I feel quite sure that if I could only get to talk their language, I should be able to learn a whole lot about what the world was like ages and ages and ages ago. You see?”

“But couldn’t some of the other animals tell you as well?”

“I don’t think so,” said the Doctor, prodding the sausages with a fork. “To be sure, the monkeys I knew in Africa some time ago were very helpful in telling me about bygone days; but they only went back a thousand years or so. No, I am certain that the oldest history in the world is to be had from the shellfish—and from them only. You see most of the other animals that were alive in those very ancient times have now become extinct.”

“Have you learned any shellfish language yet?” I asked.

“No. I’ve only just begun. I wanted this particular kind of a pipe-fish because he is half a shellfish and half an ordinary fish. I went all the way to the Eastern Mediterranean after him. But I’m very much afraid he isn’t going to be a great deal of help to me. To tell you the truth, I’m rather disappointed in his appearance. He doesn’t look very intelligent, does he?”

“No, he doesn’t,” I agreed.

“Ah,” said the Doctor. “The sausages are done to a turn. Come along—hold your plate near and let me give you some.”

Then we sat down at the kitchen-table and started a hearty meal.

It was a wonderful kitchen, that. I had many meals there afterwards and I found it a better place to eat in than the grandest dining-room in the world. It was so cozy and home-like and warm. It was so handy for the food too. You took it right off the fire, hot, and put it on the table and ate it. And you could watch your toast toasting at the fender and see it didn’t burn while you drank your soup. And if you had forgotten to put the salt on the table, you didn’t have to get up and go into another room to fetch it; you just reached round and took the big wooden box off the dresser behind you. Then the fireplace—the biggest fireplace you ever saw—was like a room in itself. You could get right inside it even when the logs were burning and sit on the wide seats either side and roast chestnuts after the meal was over—or listen to the kettle singing, or tell stories, or look at picture-books by the light of the fire. It was a marvelous kitchen. It was like the Doctor, comfortable, sensible, friendly and solid.

While we were gobbling away, the door suddenly opened and in marched the duck, Dab-Dab, and the dog, Jip, dragging sheets and pillow-cases behind them over the clean tiled floor. The Doctor, seeing how surprised I was, explained:

“They’re just going to air the bedding for me in front of the fire. Dab-Dab is a perfect treasure of a housekeeper; she never forgets anything. I had a sister once who used to keep house for me (poor, dear Sarah! I wonder how she’s getting on—I haven’t seen her in many years). But she wasn’t nearly as good as Dab-Dab. Have another sausage?”

The Doctor turned and said a few words to the dog and duck in some strange talk and signs. They seemed to understand him perfectly.

“Can you talk in squirrel language?” I asked.

“Oh yes. That’s quite an easy language,” said the Doctor. “You could learn that yourself without a great deal of trouble. But why do you ask?”

“Because I have a sick squirrel at home,” I said. “I took it away from a hawk. But two of its legs are badly hurt and I wanted very much to have you see it, if you would. Shall I bring it to-morrow?”

“Well, if its leg is badly broken I think I had better see it to-night. It may be too late to do much; but I’ll come home with you and take a look at it.”

So presently we felt the clothes by the fire and mine were found to be quite dry. I took them upstairs to the bedroom and changed, and when I came down the Doctor was all ready waiting for me with his little black bag full of medicines and bandages.

“Come along,” he said. “The rain has stopped now.”

Outside it had grown bright again and the evening sky was all red with the setting sun; and thrushes were singing in the garden as we opened the gate to go down on to the road.

The Fifth Chapter Polynesia

“I think your house is the most interesting house I was ever in,” I said as we set off in the direction of the town. “May I come and see you again to-morrow?”

“Certainly,” said the Doctor. “Come any day you like. To-morrow I’ll show you the garden and my private zoo.”

“Oh, have you a zoo?” I asked.

“Yes,” said he. “The larger animals are too big for the house, so I keep them in a zoo in the garden. It is not a very big collection but it is interesting in its way.”

“It must be splendid,” I said, “to be able to talk all the languages of the different animals. Do you think I could ever learn to do it?”

“Oh surely,” said the Doctor—“with practise. You have to be very patient, you know. You really ought to have Polynesia to start you. It was she who gave me my first lessons.”

“Who is Polynesia?” I asked.

“Polynesia was a West African parrot I had. She isn’t with me any more now,” said the Doctor sadly.

“Why—is she dead?”

“Oh no,” said the Doctor. “She is still living, I hope. But when we reached Africa she seemed so glad to get back to her own country. She wept for joy. And when the time came for me to come back here I had not the heart to take her away from that sunny land—although, it is true, she did offer to come. I left her in Africa—Ah well! I have missed her terribly. She wept again when we left. But I think I did the right thing. She was one of the best friends I ever had. It was she who first gave me the idea of learning the animal languages and becoming an animal doctor. I often wonder if she remained happy in Africa, and whether I shall ever see her funny, old, solemn face again—Good old Polynesia!—A most extraordinary bird—Well, well!”

Just at that moment we heard the noise of some one running behind us; and turning round we saw Jip the dog rushing down the road after us, as fast as his legs could bring him. He seemed very excited about something, and as soon as he came up to us, he started barking and whining to the Doctor in a peculiar way. Then the Doctor too seemed to get all worked up and began talking and making queer signs to the dog. At length he turned to me, his face shining with happiness.

“Polynesia has come back!” he cried. “Imagine it. Jip says she has just arrived at the house. My! And it’s five years since I saw her—Excuse me a minute.”

He turned as if to go back home. But the parrot, Polynesia, was already flying towards us. The Doctor clapped his hands like a child getting a new toy; while the swarm of sparrows in the roadway fluttered, gossiping, up on to the fences, highly scandalized to see a gray and scarlet parrot skimming down an English lane.

On she came, straight on to the Doctor’s shoulder, where she immediately began talking a steady stream in a language I could not understand. She seemed to have a terrible lot to say. And very soon the Doctor had forgotten all about me and my squirrel and Jip and everything else; till at length the bird clearly asked him something about me.

“Oh excuse me, Stubbins!” said the Doctor. “I was so interested listening to my old friend here. We must get on and see this squirrel of yours—Polynesia, this is Thomas Stubbins.”

The parrot, on the Doctor’s shoulder, nodded gravely towards me and then, to my great surprise, said quite plainly in English,

“How do you do? I remember the night you were born. It was a terribly cold winter. You were a very ugly baby.”

“Stubbins is anxious to learn animal language,” said the Doctor. “I was just telling him about you and the lessons you gave me when Jip ran up and told us you had arrived.”