6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

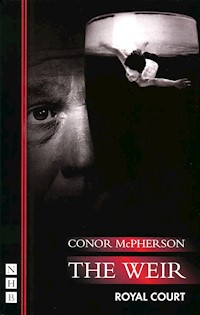

A poignant and gripping tale told through three interlinking monologues from the multi-award winning author of The Weir. Three young men from a small seaside town near Dublin tell us in overlapping monologues of their inextricably linked lives and the eventful week which was to change things for good... Winner of a Thames TV Award, a Guinness/National Theatre Ingenuity Award and the Meyer Whitworth Award. 'A touching, marvellously entertaining play which tells a gripping tale with assured panache. This is a piece of real richness' - Daily Telegraph

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Conor McPherson

THIS LIME TREE BOWER

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Foreword

Original Production

Characters

Part One

Part Two

Afterword

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Foreword

I was watching a TV programme the other night, the thesis of which was that Irish playwrights failed the Irish people during what was known as the Celtic Tiger period (roughly 1995–2007), when unprecedented prosperity raged through Ireland. The presenter of the show suggested that while Irish theatre had a duty to warn audiences that our fleeting prosperity was about to lead us to doom, in fact plays from this period tended to avoid political issues entirely. Given that I was extremely active as a playwright during these years I have to throw my hands up and say in one sense I’m guilty as charged because I’ve never written a play ostensibly about economics or politics. Suffice to say this TV programme got me thinking about what politics in the theatre really means, and what it means for the plays in this volume.

It’s twenty years since Rum and Vodka was written and performed. I was twenty years old when we did it. In Ireland at that time emigration was rampant. The eighties had seen huge unemployment and a kind of drabness pervaded everything.

However, I remember there was a feeling in the air that the nineties could be a time for positive change. Mary Robinson had just been elected as our first female president. After the Irish soccer team had reached the quarter finals of the World Cup, anything felt possible.

By the mid-nineties as borders melted away in the European Union, money and trade began to flow our way. There was a confidence none of us could remember feeling before. Coincidently, in my own field, a wave of young playwrights was flooding theatres in London, New York and beyond. Our work was being translated into many languages. It seemed as though the world was suddenly interested in what it meant to be Irish. We represented a place where a horrendous past met a glistening future and where tradition evolved.

The old monolithic enemies of change seemed to wither. Contraception was finally available in the shops. Divorce was no longer considered a fate worse than death. Single-party government was no longer possible because it just wasn’t cool any more. Young Irish people were tired of what Irish ‘politics’ had meant for so long. For us it was a term tangled up in the violence and sectarianism of our past but finally, thankfully, that all seemed to be winding down with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement.

The emergence of the Progressive Democrats, a party committed to low taxation and small government, had a massive influence. The new key to prosperity was ‘light-touch regulation’, i.e. banks and businesses needed space to prevail so governments should butt out, keep taxes low and ensure credit was unfettered. Once this idea caught hold in Ireland, a country so accustomed to poverty, it seemed like the money tap would never be turned off. Books were written about our rapid economic transformation and we were held up as an example to developing countries all over the world.

But then something darker happened, perhaps around the turn of the millennium. The insecurity at the heart of the Irish psyche reared its wild sleepy head and roared ‘Surely to Jaysus this can’t last!’ And it no longer seemed to be enough to have a job and support your family; now it felt important to shore up one’s nominal wealth in order never to be poor again. One must remember that just four or five generations previously, Ireland had experienced a catastrophic famine which altered Irish society indelibly. Deep in the Irish heart lay this almost unspoken, and truly haunting, worst-case scenario. Owning property was a blanket which kept away the bite of fear. No matter how good things seemed to be, many of the burgeoning Irish middle class were compelled to attain what they had never had before; a family house, a holiday home, and a couple of apartments to rent out as an investment. Usually each of these was obtained by securing a mortgage on the other in a draughty house of cards.

All these mortgages didn’t seem like a problem at the time because property prices just kept rising. As soon as you’d bought a property you had made money on it, so European banks were happy to lend to Irish banks who were desperate to lend to Irish people. So a construction rampage ensued. By the mid-2000s developers were building apartment blocks for foreign workers to come and live in while they built apartment blocks for foreign workers to come and live in while they… and bang, in September 2008 the credit crunch arrived. The cheap foreign money disappeared. It was payback time and we couldn’t pay.

Our economy promptly collapsed, our banks all went bust, and the whole desperate, delusional frenzy ended in a mountain of personal debt. The state stepped in to guarantee the entire country’s borrowing responsibilities but it was a disastrous bluff. We staggered on for a while but before long we ended up in the arms of the International Monetary Fund, powerless and back where we’d started in 1990. In fact it was worse, because now unemployment and emigration had returned and we owed everybody a fortune.

A litany of blame blazed across our radio airwaves for months on end. Everyone suddenly had something to say. Whereas during the Celtic Tiger nothing seemed political – only economic – now everything was political. Horrifyingly, even a group of newspaper columnists and sports commentators banded together to declare their political intentions. However, when they suddenly backed down we realised that only professional politicians truly wanted the impossible job, because it was the only job they had.

So there I was the other night, watching this TV programme about how Irish playwrights apparently failed to write about all this stuff, but over the next few days I began to wonder if the programme was actually missing the point of what art does and how time reveals it. I had a look back over the successful plays from the time and speculated if (like looking at the rings in a fallen tree) it’s possible to argue that our theatre history contains the unmistakable mark of its climate at this time.

The nineties in Irish theatre will probably always be associated with the monologue. Almost every successful new play that emerged from Ireland at the time had an element of direct storytelling. It was as though the crazy explosion of money and stress was happening too close to us, too fast for us, making it impossible for the mood of the nation to be objectively dramatised in a traditional sense. It could only be expressed in the most subjective way possible because when everything you know is changing, the subjective experience is the only experience. For example, a seemingly modest play like Eden by Eugene O’Brien – which consisted of a married couple speaking directly to the audience for two hours in the Abbey Theatre’s studio space – became a smash hit. It was revived, toured and transferred to the bigger Abbey space, returning again and again over a period of about two years. It even made it to the West End (where admittedly the British critics scratched their heads and wondered at its native popularity).

I would suggest that the hunger for this kind of highly personal work was unprecedented because the whole phenomenon of living in Ireland at the time was unprecedented. It has been argued elsewhere that a secular need flooded the space left by the disgraced Catholic Church and a contemporary dearth of true political leadership. We still had souls, but we just couldn’t trust anyone with them any more. Thus monologue theatre flourished because it was a mirror which took you inside your own eye. The work had to become more private and the humour more painful in order to reflect the mood of an audience who didn’t feel like they were living in a sustainable reality on any level. Big old ‘state of the nation’ plays simply couldn’t have reflected that feeling, I don’t think. The dramatic problem was far subtler than before so the successful plays of the time took a subtler approach.

As young writers, we knew of Beckett’s great monologue plays and Brian Friel’s iconic Faith Healer, but these were examples of a form rather than the norm. When one considers the tumultuous time in which this form re-emerged and became almost ubiquitous it doesn’t feel like mere coincidence, and I would contend that to dismiss such a sea change in Irish drama is to ignore how well it charted the peculiar history of the Irish mind for its time. And all the more so when one considers how organic and unconscious this movement was. It just happened. The more Ireland’s economic fortunes appeared to catapult us into a twenty-first-century orbit, the more our theatre seemed determined to return us to an almost ancient mode of storytelling.

For myself, I haven’t written a monologue play for well over a decade now. This year I am forty and consider myself extraordinarily fortunate to have worked as a playwright for the last twenty years. The hard-won perspective of the intervening time shows me that I thought I was free and independent back then, but now I know I was struggling with history just like everybody else. I used to find it so difficult to even think about my own past work. I always felt the need to look away into the future. But as I enter middle age I look back with a more forgiving regard. I read the very first line of the first play in this volume, which says: ‘I think my overall fucked-upness is my impatience.’ It was true then, and it’s true now, and probably not just for me. And maybe that impatience drew me to the monologue form. Because it could take you right where you wanted to be so fast and keep you there because it just felt real.

At every performance the audience suspend their disbelief. They know they are watching people pretending yet they believe they are seeing something real and true. This is the magic of theatre, and it’s purer than film because the audience generate this belief without any of the aids of cinema. A bare story told by a single voice in the theatre can distil this experience even further. Of course it takes a good story and a good actor to tell it. And of course it’s probably not for everybody, but for those who like theatre for precisely what it can do best, i.e. create a world out of nothing, this kind of work can be surprisingly memorable.