1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

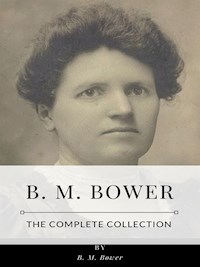

In "Trails Meet," B.M. Bower crafts a vivid tapestry of life in the early 20th-century American West, meticulously weaving themes of love, resilience, and adventure into her narrative. The novel, marked by Bower's signature blend of lyrical prose and sharp dialogue, captures the rugged yet enchanting landscapes that define this period. Through rich descriptions and compelling character interactions, Bower invites readers into a world where trails converge, mimicking the intertwining lives of those who traverse them. The setting serves not only as a backdrop but as a character in itself, embodying both the challenges and beauty of frontier life. B.M. Bower, a prominent figure in Western fiction, drew inspiration from her own experiences as she settled in Montana. Her firsthand encounters with the American frontier, combined with her understanding of the era's cultural dynamics, shaped her storytelling. Bower's genuine admiration for the characters she portrays 'Äî brave women, resourceful men, and the intricate communities they build 'Äî brings authenticity to her narratives, allowing her to challenge stereotypes prevalent in her time. This captivating novel is a must-read for enthusiasts of Western literature and those drawn to tales of personal growth against the backdrop of nature's splendor. Bower's engaging style and profound insights make "Trails Meet" an enriching experience, encouraging readers to reflect on their own journeys and the connections they forge along the way.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Trails Meet

Table of Contents

I. — DEATH ON THE TRAIL

THE wind rocked the flimsy cabin. At times the gale would die, then rain that was half sleet would whip against the one small window facing the storm. Smoke that would not rise above the rock chimney when the gusts came fiercest was buffeted back down into the fireplace and out into the big room.

Jess coughed when a particularly acrid billow surged out into his face. As he turned and groped half-blinded to the door, he stopped and listened. It might have been imagination, or it could have been the far-off ululating howl of a coyote. He thought for a minute that some one shouted. Chuck, maybe.

He pulled open the door and stood there, coughing the smoke from his lungs. It couldn't have been Chuck yelling. Chuck was either at the ranch or he was in town at that moment, and if he yelled at all it would be in the exuberance of his unexpected vacation. He wouldn't be coming back to-night; not if he could help himself.

The door opened toward the valley and was partly sheltered from the wind. The rain and sleet drove past slantwise, silvery needles in the faint light shining through the doorway. A wild night, sure enough. Jess wished now that he had gone with Chuck. He had thought it would be good to have the cabin to himself for a night or two; privacy bought with loneliness. Not much use if this storm kept up. He was turning back into the cabin when a gun roared out somewhere along the trail.

Instinctively Jess ducked aside out of the light. No bullet whined in his ears, however, nor did he hear the thud of an impact against the wall. No one would be shooting at him, anyway; at least, not with any reason he could think of. Still—

Again that shout or call; just what it was he could not tell, with the wind roaring over the roof and the rain hissing past, but there was no mistaking the abrupt pow-w of the shot that followed. Not a hundred yards from the cabin, Jess thought; and when upon that echo of that shot there followed three more in rapid succession, he had a flash of understanding. Some one out there was in trouble, trying to call for help; down around the thicket, or the six-shooter's flare would have shown even in the deluge of rain. A shot would of course carry farther than a shout, though the man was trying both.

Jess took his lantern off its peg and lighted it, stepped to his bunk and pulled his own gun from its holster on the belt hanging beside his pillow; and the second act was quite as natural to him as the first. Darkness made a light necessary. And trouble of which he knew absolutely nothing might need a gun for settlement. His pioneer blood told him that without a moment's hesitation or doubt.

Yet his pioneer blood could not keep his heart from thumping a little harder than usual as he bent his head to the storm and went off down the trail, gun ready in his right hand, the lantern swinging from his left. No telling what he might be walking into. His lips twitched with a passing smile as he thought of the target he was making of himself with that lantern, but even as he thought it, he was observing too the silvery slant of the rain across the moving zone of light, the fantastic bobbing shadows, the dark, writhing blur of bushes as he passed them. He was debating upon the exact shade of lantern light in a storm. He was wondering if Chuck could by any far-fetched possibility be hurt and helpless a hundred yards from camp.

These thoughts did not shorten his stride, so presently he rounded the thicket and halted just where the light revealed a man huddled in the middle of the trail like a bundle of old clothes, one tail of his coat snapping in the wind.

Jess slid his gun into his coat pocket and set down the lantern, which immediately tilted over on its side and threatened to go out. But not before it revealed the man's face and the cringing fear in his eyes; a look strangely at variance with his frantic calls for help.

Jess righted the lantern, turned the wick to a safer height and looked again. "What's the matter, Mr. Parsons? How are you hurt?" He stooped, shielding the injured man as well as he could with his body.

"Rob—young Robison!" Even with the groan that followed the jerky speech, a note of relief was in the voice. "Get me—get me out of this—quick, before—" He groaned again.

"But what happened? Your horse fall with you?"

"Horse? No—they followed—I'm shot. For Godsake do some—get me in—"

"Sure." Jess was sliding the lantern bail into the crook of his arm so that his hands would be free. He hesitated, glanced behind him and blew out the light. Foolish, maybe. If some one had shot Parsons and was following, those last signal shots would tell where he was. Still, it might be as well not to advertise the exact spot with a light. "Can you walk if I hold you up? It's only a short way." He fumbled for the man's armpits as he spoke.

"Treacherous devils—" Parsons groaned. "No, I—my strength's gone. I—I dragged myself this far—"

"Well, all right. I'll pack you, then." Jess knelt on one knee, fumbled for Parsons' arms, hauled the limp burden on his back. Albert Parsons was a small man yet it was not easy to handle him, twisting and groaning, with the gale pushing and tugging with malevolent fury. Jess went tottering under his load, short steps feeling out the way. He knew every inch of that trail, he could have walked it blindfold, yet the storm confused his sense of distance and made it seem farther. He was thinking he must have passed the cabin and was headed for the corral, when his foot struck against the doorstep and almost sent him sprawling. He had a fantastic impulse to laugh when Parsons' head butted against the cabin wall and his groans broke off in a yelp of surprise. He did not like Parsons, anyway.

For that reason perhaps he staggered across the room and let down his burden on Chuck's bed which stood opposite his own. Chuck would raise a howl when he found out about it, but that did not worry Jess now. He wanted to see just what was wrong, how badly Parsons was hurt. It seemed somehow indecent for a grown man to do so much moaning and complaining, no matter how badly he was injured. He was not so sure Parsons couldn't walk if he wanted to.

Nothing of this appeared in voice or manner. "Better get you into bed, hadn't I? Then we can take a look-see. Wait a minute. I think I can scare up a little whisky—just for a bracer."

Chuck would raise a howl about that too, Jess supposed. Chuck valued his eye-opener more than he did the breakfast which followed it, as a rule. He kept the bottle hidden behind the dish cupboard and he never produced it for the refreshment of callers. Jess very much doubted whether Chuck would have brought it forth for Parsons even in this emergency. Chuck didn't like Albert Parsons either. No one did, so far as Jess knew.

But presently he forgot Chuck's little idiosyncrasies, forgot even his own instinctive aversion for the resident manager of the Diamond Slash ranch. When he brought the lamp over and removed Parsons' upper garments, he stared aghast at the hole three inches below his heart. It seemed incredible that Parsons had been able to move at all or to shout for help. Certainly he could not have crawled far. The wonder was that he was alive, Jess thought.

"Say, I'd better try and get a doctor out here," he exclaimed. "Or I could make it to the ranch with you, and have them 'phone—"

"No!" Parsons almost screamed the word. "Give me another—drink of that—whisky." He swallowed the liquor with a gulping greed that curled Jess's fine mouth with disgust. "No—here's where I want—not the ranch, for Godsake!" He gave a groaning sigh as Jess lowered his sleek black head to Chuck's pillow.

"Why not? You're the big chief there. What you say goes, it seems to me. Sure, that's the place for you, soon as this storm lets up a little so I can haul you over there." Jess had brought hot water, a bottle of antiseptic lotion, a package of cotton. "I don't know if it's a good sign, but there isn't much blood now. You bled at first, judging by your clothes, but it's almost stopped. I'll fix you up best I can, and then—"

"I'll stay here," gasped Parsons, taking short, panting breaths. "Treacherous devils—they'd finish me." He swung his little black eyes sidewise until they rested upon Jess. "My boot—the left boot—it's—you—I—take it—"

"All right. Don't you worry, Mr. Parsons. I'll fix it." Jess slowly pulled the soft, expensive riding boots off Parsons' feet, careful not to jerk. While he worked them down off the heels, he watched Parsons' face, ready to ease the pull at the first sign of distress. For that reason he did not see the letter that slid out of the left bootleg and lay just under the edge of the bunk. As the second boot came off he pushed the pair back out of the way. The letter skated under Chuck's suitcase and lay snug and unseen, Jess never suspecting its existence.

"Dirty frame-up," Parsons was muttering. "Trying to double-cross me, too. I—know too much—more than—"

"Sure," Jess soothed him while he washed the wound and made ready a compress. He was not thinking of the things Parsons said nor could he have repeated the words two minutes after they were spoken. He was wondering what he could use for a bandage and he was thinking how Chuck's eyes would pop open if he should walk in and see what was going on. He didn't like the look in Parsons' face, either, nor a certain rattling sound in his throat when he breathed. Though Jess never had seen death take hold of a man, instinct warned him now that it was coming close to Albert Parsons.

"Wheels within wheels—I told them they couldn't get away with it, and this is—If you can keep your mouth shut—keep quiet—" His beady black eyes bored like twin gimlets into Jess.

"Certainly. And so must you, keep as quiet as you can." Jess stood up, listening to the storm rather than to Parsons. It would be madness to try taking the man anywhere and if he left him here alone while he went for help—

Parsons sensed that thought. "Don't leave me alone—I'm afraid they followed—you stay here, Jess—I've got to tell you—"

Jess moved away from the groping hand that wanted to get hold of him and cling. He hoped he wasn't brutal, but he felt a distinct aversion to being clung to by Albert Parsons either dying or in health. "I ought to get help," he covered his retreat. "You're in a bad way, I suppose you know. I've done all I can do, Mr. Parsons."

"All anybody can do," groaned Parsons. "Stay here. I'll tell you—something big. You can clean up—if you work it right. Sarky—little Sark—"

"You better not talk any more, Mr. Parsons. Maybe if you are quiet you'll—" The lie stuck in his throat. Quiet or not, Parsons couldn't last the night out.

"I want to tell you something—serve the damned fools right."

"Just as well if you didn't. I don't want to know."

"Not if there's real money—all yours if—"

"It's getting cold in here," Jess parried. "I'll have to fix the fire."

While he rebuilt the fire and set the coffeepot close to the flames on the hearth, he revolved in his mind the problem thrust upon him. It wasn't simple. To ride ten miles or more in that storm was an ordeal any man would shun. For one thing, there was Jumper Creek to cross before he reached the valley on his way to town. He shook his head dubiously when he thought of the steep sidling trail down along the bank to the water's edge. Soft soap would be sticky alongside that fifty yards of clay right now, and as Chuck once had declared, it only took a bucket or two of water to send Jumper Creek on the rampage. If the rainfall chanced to be heavier up along its source, the tricky little stream would be a rushing torrent which no man in his senses would attempt to cross in the dark.

Of course, he could ride to the Diamond Slash which was not half as far away as town. He could go along the north side of the creek to the bridge just this side the ranch gate. But Parsons seemed afraid of the Diamond Slash for some reason—his own outfit!—and even if he wanted to go home it would be the deuce of a job to drive a team over that trail in the dark, there were so many twists and turns through the rocks. Even in daylight it would be rough riding for a wounded man. Moreover, there was no rig in camp except the wagon, and that was down by the corral with a load of fence rails—unless they had blown off. The wagon box was up near the cabin and it would be next to impossible for one man to lift the box on the wagon, especially at night. In a howling gale like this—Jess shook his head again and dismissed the thought as useless. Much as he hated it, Parsons would have to lie there on Chuck's bunk for the present.

He looked at the coffee and found it almost hot, poured a cup and carried it to the bed. "Maybe a drink of this will make you feel better, Mr. Parsons—" He stopped abruptly, set down the cup with a startled motion that spilled half its contents, and picked up the lamp for a closer look at the man. And as he moved the light toward the bed, the door was flung open, letting in a whooping gust of wind.

The flame flared up in the lamp chimney and went out, leaving the cabin black for a moment until his eyes adjusted themselves to the dull glow of the fire still eating sullenly away at the fresh wood. Two slickered forms pushing in through the door were blotted out, then became vague shapes halting uncertainly just within the room while one forced the door shut behind them.

"That you, Chuck?" The first figure stumbled toward him.

"No, this is Jess. Wait a minute. I'll light the lamp. I'm certainly glad you blew in right now. Tom Ritchie, isn't it?"

"Blew in is right!" grumbled the second man, giving the door a kick for good measure.

"Oh, hello, Bob." A match flared in Jess's fingers, throwing his face into the sharp relief of a cameo. A fine, sensitive face, sobered now and made stern by the tragic experience thrust upon him within the past hour. He tilted the lamp chimney, drew the flaming match across the hot wick, dropped the chimney into place and looked up at the two. "You're looking for Albert Parsons, aren't you?"

Blank silence for a startled breath or two. Tom Ritchie, foreman of the Diamond Slash, took a step forward.

"Who told you that?"

"Nobody. I just guessed maybe you were."

"Why?" Ritchie demanded. "He been here?"

Jess lifted the lamp again, moved it so that it shone full upon the bunk. "He's here now. Take a look. I think he's dead."

II. — OTHERS COME SEEKING

JESS heard the sibilant sound of a man exhaling a breath under stress of emotion. It may have been Ritchie or the cowboy, Bob Francis; he rather thought it was Bob. He also fancied that there was some wordless message passing behind his back. Then he pushed the thought away as sheer nerves; the two moved up beside him, wet slickers rustling as they walked.

Ritchie pulled off his streaming Stetson. "My God, he's done it, Bob," he said in a low, shocked tone,

"Only for the storm, we'd maybe have found him in time to stop him," Bob muttered, pulling off his own hat in tardy remembrance of his manners.

It was all Greek to Jess,—Parsons with his frantic terror of some unnamed enemy seeking to kill him, and now these two plainly assuming that Parsons had killed himself. While they stood staring in stunned silence, he studied them with swift observant glances. He noted the sleek gloss of wet hair against temple and cheek, the high light on noses, chins, cheek bones, the shine of downcast eyes glinting between their lids. Caught within the momentary spell of line and color, he forgot the dead man lying in sodden inertness before them. Ritchie's inscrutable mouth was compressed with some sterner emotion than grief for a fellow employee. Bitterness touched those corners, Jess thought. Bitterness, perplexity, certain other hidden things were there—but not grief.

Ritchie reached a long, deliberate arm, pulled a fold of gray blanket over those snaky black eyes staring so fixedly at nothing, and turned sharply away toward the fire. As though released from some hateful restraint, Bob Francis sighed deeply and followed his boss.

"How the devil did he get here?" Ritchie asked with abrupt harshness, and dropped his hat on a bench that he might unbutton his slicker and let warmth in to his chilled body.

Jess set the lamp on the log mantel in the exact position it should occupy to make a balanced picture, and was only subconsciously aware of the effect afterwards. "On my back," he said, and moved an old brass tobacco jar half an inch to the left.

"On your back?" Ritchie's voice had a strained sound as if he were holding it rigidly under control.

"Yes. I heard what seemed to be signal shots just down around the first turn. I went down there and it was Parsons, lying all humped up in the middle of the road."

"You heard—down around the turn—" Bewilderment rode Ritchie hard. He turned and looked at Bob Francis, who kicked a brand back into the fire and muttered something under his breath. Ritchie turned back to Jess. "You heard him—shoot himself that close to here?"

"I didn't say that. I said I heard three or four shots. One, and then three more. Just as I came up with the lantern, he fired again, into the air."

"Hunh." Ritchie glanced toward the bunk and lowered his voice in deference to the dead. "I don't get it. Damned if I do. Here's how it is, Jess. This thing has been building for over a week. Al's been drinkin' like a fish lately. Last day or so I thought he was in for a spell of snakes, but he went off his nut about enemies trying to kill him. This morning he got up wishin' he was dead. Said for half a cent he'd blow himself to hell. I didn't think so much of that—he's talked that way before, after a spree."

"That's right," Bob interjected into the pause.

"Most generally Al'd take another drink or two and forget it. To-day, though, he turned sulky. Kept muttering things like how he'd be better off dead, and so on. Right after dinner he ordered his horse and rode off down the valley. Bob, here, knows the frame of mind he was in—" He broke off, glancing at young Francis.

"Yeah," Bob responded, "he sure wasn't in no condition to be off by hisself with a shootin' iron handy. I thought at the time—"

"You should of come and told me when he went," Ritchie reproached him. "I'd 'a' kept him home if I had to hog-tie him." He looked at Jess. "He must have had a bottle with him. Sure smells loud enough."

Jess moved his head slowly from left to right and back again. "What you smell is some whisky I gave him. Two drinks. Chuck had some in camp."

"Ain't got any left, I s'pose?" Bob hinted broadly, but Ritchie stopped him with a frown.

"Didn't Al have a flask on him? You went through his pockets, didn't you?"

Anger flared and as quickly subsided in Jess's greenish hazel eyes. Probably Tom Ritchie failed to realize how that sounded. One had to make allowance at a time like this.

"No," he said quietly, "I most certainly didn't go snooping in his pockets. I was busy trying to keep him alive." He glanced over his shoulder toward the shadowed corner. "I couldn't do much. No one could, I think. He was too far gone when I found him."

"Wasn't he able to talk—explain himself? Didn't he give any reason for doing it?" Ritchie had his slicker off and was lighting a cigarette. Jess wondered if it were only the match blaze which gave that strange shifty look to his eyes. "He said something, didn't he?"

"Not much. A few disjointed sentences—I was too busy to pay much attention."

"Well, what kinda sentences?" Ritchie's narrowed eyes watched Jess fixedly.

"Oh, he called me by name when I found him and he said he was shot. He asked me to get him in out of the storm. Of course he was groaning a great deal. Getting him on my back must have hurt him most damnably. I can see that now. At the time, I thought he was making more fuss than was necessary."

"He must of said more than that," Ritchie objected. "He was able to recognize you by lantern light; what else did he say?"

"Oh, he said his boots hurt him, so I managed to pull them off. It was after that I gave him the whisky. He asked for more. He was muttering—all incoherent, nothing lucid except that he kept telling me to stay with him. I'm sure he felt he couldn't last long, though he didn't say so."

Ritchie's cigarette was cold. He lighted another match and held it up, but his hand shook so that he could scarcely set the tobacco afire. Jess watched him, wondering what thoughts went shuttling back and forth behind that studying frown.

"Damn funny he didn't have more to say than that," he said finally, flipping the burnt match into the fire with an impatient gesture. "You hear what he muttered about?"

"I was on the jump, remember. He was suffering terribly, groaning and moaning. And it really wasn't long; not more than an hour, perhaps not that long. I had no thought of time, just of doing what I could to ease him."

"Nobody to blame but himself," Bob Francis volunteered. "He—"

"Cut that out, Bob," Ritchie growled savagely. "I hate a coward same as you do, and a suicide ain't nothing but a damn coward. But he's gone now—and anyway, he must of been crazy."

"He sure was," Bob made emphatic agreement.

"Well, the thing's done, and what we've got to do is play up. I know damn well the Senator would do anything in the world to keep this out of the papers. His old friend and ranch manager committing suicide would sure look bad right now, just when they're tryin' their damnedest to frame something on him."

"That's right," Bob Francis echoed. "It sure would be bad right now."

"We've got to make out it was some accident." Ritchie eyed Jess sidelong. "Out hunting—gun went off accidentally—what d'you think, Jess?"

"You might possibly get away with it, Tom."

"We've got to get away with it. There's a bunch out to get the Senator any way they can. Knife him in the back, if they thought they'd get by with it. They're afraid of him, that's why. He's too honest and too powerful. They know they can't buy him, so they aim to do the next best thing and bust him. They sure would love to get hold of something like this."

Jess pulled his gaze away from the fire. "I don't see how they could use this against Senator Wolsey. Isn't he still on the Coast?"

"Yeah, but that wouldn't stop 'em. Al and the Senator's been cronies for ten years and more. You got no idea what raw deals they try to pull nowadays. Politics is sure rotten."

"Well, listen here," said Bob Francis. "Far as me and Jess knows, Al was out huntin' and shot himself accidental. Ain't that right, Jess?"

Jess lifted an elbow from the mantel, pushed back an unruly lock of brown hair and said nothing at all.

Ritchie's nostrils suddenly flared like a fractious horse. "He didn't say he meant to kill himself, did he?"

Jess's fingers lay still on his right temple. "No. He said, 'I'm shot.'"

"Well, that could mean an accident, couldn't it?"

"Certainly."

Ritchie sighed heavily. "Al was about as careless with a gun as any man I ever saw. For all I know or you know, it was an accident. About where—?"

Jess lifted his head and looked at Ritchie. "Do you want to see the wound?"

Something in Ritchie's eyes retreated. He seemed to wince, though Jess saw no movement. A mental flinching, he thought it was. "Where was he—shot?"

"In the side," Jess said simply. "A little to one side and below the heart. Do you want—"

"N-no, I'll take your word for it. Damn it, I hate to think—he was such a—"

"A crazy man isn't responsible for his acts."

"Sure. That's right." Ritchie covered a shudder with a swift shrug. "Sure, that's right." He seemed to be studying something and he seemed to be relieved. "There'll be an inquest, of course. But that's all right. I'll fix that." His spirits rose almost to cheerfulness. "You won't have to be called, even. Unless—how about it, Jess? You want to get mixed up with this, or not?"

"Not if I can help it, Tom. I—never did swear to a thing I didn't believe was the truth." He looked from Tom to Bob. "If I had to testify before a coroner's jury, I'd tell the truth."

"Any different from what you just told us? That sounded like an accident to me; why you so damned sure it wasn't?"

"That isn't the way I put it, Tom. As a matter of fact, I don't know anything except that he was shot and that he's dead. I am entitled to my opinion, I hope. And I certainly don't think it was accidental. Nothing he said gave me that impression."

Ritchie was watching every line and expression of his face, but Jess was well schooled in keeping his thoughts from revealing themselves without his consent. Ritchie turned, baffled, and looked at Bob.

"Maybe Jess didn't tell all of it," Bob shrewdly hazarded.

"Parsons means nothing to me. Why shouldn't I tell all he said?"

"That's for you to answer yourself. Put us under oath and about all we could tell for a fact was that we started out looking for Al because he wasn't able to ride out by himself. Wasn't safe, rather. We get caught in this storm and head for your camp, and we find Al here dead and you alone with him. He's been shot. Now, that's as much as we know. We don't think you had anything to do with it, because we both know you. But a bunch of strange men could take them facts and think something entirely different. So you see, all you can tell us won't be a damn bit too much."

"I've already told you why I went out and brought him in and what he said. He was suffering terribly, remember. I feel sure he was dying when I found him, but at the time I was peeved because I had an idea he could have walked if he had wanted to make the effort. He couldn't. I know that now."

"Didn't he say any more than just what you told us?"

"A little. I told you he mumbled about his boots hurting him, and then when I said I'd get help, he understood that, for he said, 'Stay here!' And again, 'Don't leave me.' And he asked for whisky."

"All that don't prove a damn thing about how he come to do it."

"No, it doesn't." Jess stooped to thrust a fallen stick back into the blaze. "But if it had been an accident, I think he'd have said so. People are always wanting to tell exactly how it happened when they have an accident. The suddenness excites them into talking."

"College notion. Sounds like psychology. But it's the bunk when you come to real life." Ritchie became silent, frowning at the fire. Bob Francis waited anxiously, trying to keep his eyes from straying toward the corner where Parsons lay dead.

"Well, we oughta be comin' to some kinda agreement," he ventured nervously at last.

"Agreement's made," Ritchie said shortly. "If Jess keeps his mouth shut, we'll pack Parsons home and I'll do the rest. How about it, Jess?"

"You asked that once," Jess retorted. "It's your affair, not mine. All I did was carry him in here and do what I could for him; which was mighty little."

"If we handle this like I said we'd oughta, you'll have to forget the whole thing. No need to blab around about carrying him in here. We'll claim we found him out on the trail somewhere. We would of, if he'd been left where he was at."

Jess turned and looked straight into his face. "I'm not in the habit of blabbing what doesn't concern me. And if you think I'd leave a hurt dog out in all this storm—"

"Now, you got me all wrong. No need to get sore. Maybe I spoke outa turn, but this burns me up. Coming right now, it'll do the Senator more harm than murder. The opposition wouldn't like anything better than to say his ranch manager got guilty conscience or something and killed himself. They'd sure spread it all over the front page of every paper in the country."

"I don't see—"

"'Course you don't see. You don't know the dirty double-crossing deals the Senator has been side-stepping. He's too many for 'em or they'd have had him railroaded or put on the spot long ago. That's why this has got to be kept outa the papers. I can make it stick with the coroner as an accident. I'll have to pull a fast one, but I can do it if you forget you know anything. Being friendly with the family, you oughta help protect the Senator."

Jess turned away. "I still don't see how this would affect him, but maybe I'm just dumb. Go ahead, call it what you please. I sha'n't say anything unless I'm dragged into it—and I don't suppose it matters to Parsons."

"Be a favor to him. You know that. I'll have to tell the Senator the truth—after the danger's all past. He'd sure appreciate your help, I know that. And I can tell you one thing, old kid, Senator Thomas Wolsey is a man that never forgets a kindness. You may never know just all this'll mean to him, but you can be damn sure you won't lose nothing by it."

"I certainly don't expect to profit anything by it," Jess said shortly. "I don't want to."

"Maybe you will more'n you know. You don't know what it's all about, but politics is a cutthroat game. A man as square as the Senator has got to keep his back to the wall and both eyes peeled every minute. Enemies on every side ready to knife him in the back—frame-ups—wheels within wheels—"

Jess bent quickly to the hearth, hiding the start he gave. Wheels within wheels—it almost seemed like the dead man's voice repeating the words. He stole a glance toward the bunk as he stood up, but his voice was calm and unconcerned. "Coffee's boiling. A good hot cup will just about hit the spot, I should think."

"Damn right. We've got to beat it away from here with the body, storm or no storm."

"Slackin' up some," Bob Francis grunted. "Better not wait too long. Let the rain wash out our tracks."

"That's right. You got a head on you. Me, I ain't used to these secret p'formances." Ritchie smiled bleakly at Jess. "Wouldn't chance it for anybody else. Hope I'm never called on again for a job like this, but so long as we all think the same, I'm satisfied."

Jess filled two straight-sided white enamel cups with strong black coffee. As for himself, he felt that it would choke him now while that grim figure lay so quiet in the shadowed corner. He wondered how these two could be so unconcerned, and at the thought he lifted his eyes and studied them shrewdly.

Ritchie was still remarking upon the simplicity of covering up the facts so that no harm would come of the suicide, but even while he declared his certainty, Jess noticed that his hand shook like an old man with palsy. And Bob Francis, bending his head thirstily to the cup, was pasty gray and his mouth was loose, his lips trembling. A shock of complete understanding rippled along Jess's nerves. Say what they pleased, Tom Ritchie and Bob Francis were scared, terribly scared of something which neither had mentioned at all.