Uncle Tom’s Companions: Or, Facts Stranger than Fiction. A Supplement to Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Being Startling Incidents in the Lives of Celebrated Fugitive Slaves E-Book

Frederick Douglass

1,82 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Krill Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 493

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

UNCLE TOM’S COMPANIONS: OR, FACTS STRANGER THAN FICTION. A SUPPLEMENT TO UNCLE TOM’S CABIN: BEING STARTLING INCIDENTS IN THE LIVES OF CELEBRATED FUGITIVE SLAVES

Frederick Douglass

FIREWORK PRESS

Thank you for reading. In the event that you appreciate this book, please consider sharing the good word(s) by leaving a review, or connect with the author.

This book is a work of nonfiction and is intended to be factually accurate.

All rights reserved. Aside from brief quotations for media coverage and reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form without the author’s permission. Thank you for supporting authors and a diverse, creative culture by purchasing this book and complying with copyright laws.

Copyright © 2015 by Frederick Douglass

Interior design by Pronoun

Distribution by Pronoun

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

PREFACE.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS.

JAMES PENNINGTON, THE FUGITIVE BLACKSMITH.

CHAPTER I. THE MASTER AND HIS SLAVES.

CHAPTER II.LIFE STAKED FOR LIBERTY.

CHAPTER III. HOPE SUPPORTS, AND FREEDOM AWAITS HIM.

JOSIAH HENSON.

WILLIAM WELLS BROWN.

HENRY BIBB.

HENRY HYLAND GARNET.

MOSES ROPER.

PETER WHEELER.

CHAPTER II. PETER’S LOT GROWS HARDER THAN BEFORE.

CHAPTER III. THE MASTER PUNISHED, AND THE SLAVE SET FREE.

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS.

APPENDIX.

REPORT OF THE SPEECH OF FREDERICK DOUGLASS, THE AMERICAN SLAVE,

Uncle Tom’s Companions: Or, Facts Stranger than Fiction. A Supplement to Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Being Startling Incidents in the Lives of Celebrated Fugitive Slaves

By

Frederick Douglass

Uncle Tom’s Companions: Or, Facts Stranger than Fiction. A Supplement to Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Being Startling Incidents in the Lives of Celebrated Fugitive Slaves

Published by Firework Press

New York City, NY

First published circa 1895

Copyright © Firework Press, 2015

All rights reserved

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

About Firework Press

Firework Pressprints and publishes the greatest books about American history ever written, including seminal works written by our nation’s most influential figures.

INTRODUCTION

UNCLE TOM’S COMPANIONS: OR, FACTS Stranger than Fiction. A Supplement to Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Being Startling Incidents in the Lives of Celebrated Fugitive Slaves was released following the success of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.It describes the experiences of a number of slaves, including Frederick Douglass, Josiah Henson, William Wesll Brown, Henry Bibb, and more.

PREFACE.

IF EVER A NATION WERE taken by storm by a book, England has recently been stormed by “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” It is scarcely three months since this book was first introduced to the British Reader, and it is certain that at least 1,000,000 copies of it have been printed and sold. The unexampled success of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” will ever be recorded as an extraordinary literary phenomena. Nothing of the kind, or anything approaching to it, was ever before witnessed in any age or in any country. A new fact has been contributed to the history of literature—such a fact, never before equalled, may never be surpassed. The pre-eminent success of the work in America, before it was reprinted in this country, was truly astonishing. All at once, as if by magic, everybody was either reading, or waiting to read, “the story of the age,” and “a hundred thousand families were every day either moved to laughter, or bathed in tears,” by its perusal.

This book is not more remarkable for its poetry and its pathos, its artistic delineation of character and development of plot, than for its highly instructive power. A great moral idea runs beautifully through the whole story. One of the greatest evils of the world—slavery—is stripped of its disguises, and presented in all its naked and revolting hideousness to the reading world. And that Christianity, which consists not in professions and appearances, but in vital and vitalising action, is exhibited in all-subduing beauty and tenderness in every page of the work. If ever a book had a mission, that book is “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Its mission is to attract all readers to it by virtue of its many charms, and after attracting them, warm them with an enthusiasm, and fill them with a love of Humanity—and unmistakably and admirably has this mission so far been fulfilled. And it will continue to be fulfilled as the years pass away, and the empire of Injustice gradually crumbles before the advancing tide of a Christianised Civilisation. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” will not only be read by Englishmen, and those who talk the English language, all the world over, but it will be translated into all the principal languages of Europe, and become a household book for ages.

This book, as it is now well known, depicts with graphic force Negro life in the United States. That it does this with as much truth as vigour, will be seen by a perusal of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” But as the truthfulness of the delineations of Mrs. Stowe’s book has been called into question, and the inferences drawn therefrom disputed by the Times newspaper, and other authorities, such a book as “UNCLE TOM’S COMPANIONS” was demanded. It has been said that “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” is an exaggeration, that it misrepresents Slavery and Slaveholders, and that its influence must be prejudicial in riveting more closely the chains of the poor slave, and protracting the hour of his emancipation.

The Times, in speaking of Mrs. Stowe and her book, says—"That she will convince the world of the purity of her own motives, and of the hatefulness of the sin she denounces is equally clear; but that she will help in the slightest degree towards the removal of the gigantic evil that afflicts her soul, is a point upon which we may express the greatest doubt; nay, is a matter upon which, unfortunately, we have very little doubt at all, inasmuch as we are certain that the very readiest way to rivet the fetters of slavery in these critical times, is to direct against all slaveholders in America, the opprobrium and indignation which such works as ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ are sure to excite. . . . . The gravest fault of the book has, however, to be mentioned. Its object is to abolish slavery. Its effect will be to render slavery more difficult than ever of abolishment. Its very popularity constitutes its greatest difficulty. It will keep ill-blood at boiling point, and irritate instead of pacifying those whose proceedings Mrs. Stowe is anxious to influence on behalf of humanity.” The long and elaborate review concludes with the following words—"Liberia, and similar spots on the earth’s surface, proffer aid to the South, which cannot be rejected with safety. That the aid may be accepted with alacrity and good heart, let us have no more ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabins’ engendering ill-will, keeping up bad blood, and rendering well-disposed, humane, but critically placed men their own enemies and the stumbling-blocks to civilisation, and to the spread of glad tidings from Heaven.”

Mrs. Stowe has either told the truth or she has not. If she has told the truth, it was right and proper that she should tell it, whether slaveholders were offended or pleased. The Times admits that slavery is an evil. If so, let the evil be exposed, whoever may be displeased. But if, on the other hand, Mrs. Stowe has not described truly, if her pictures be false, and her reflections erroneous, then will her book in the long run be considered of little value,and be soon consigned to the oblivion it merits. But Mrs. Stowe has not overdrawn the picture, she has only painted slave life as it is, and because she has spoken truly, the influence of her book “will be vast and immeasurable.”

The object I have in writing “Uncle Tom’s Companions,” is to vindicate “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” and to refute the unjust criticisms of the Times, and all who think with that paper. I have done this by simply narrating passages in the lives of fugitive slaves—of men who have passed through the fiery furnace of slavery, and escaped, though not unhurt, to the land of freedom—of men, some of whom are now in England, and who cannot return to their native country on account of the Fugitive Slave Law. I have drawn no imaginary picture, I have summoned no ideal characters on the scene, and thrown around them the hues of my own fancy; but I have called as my witnesses men, living men—men who have walked, or who are now walking, the streets of London, but who a few years ago, suffered all the horrors which slavery inevitably inflicts. And they are not witnesses whose names are unknown. No, but those of Frederick Douglass, Dr. Pennington, the Rev. Mr. Garnett, William Wells Brown, and others, with whose views, or whose writings, a large proportion of the English public are familiarised: These men have been, and are “Uncle Tom’s Companions.” They were his companions in slavery and in suffering, and it is right that their story should be told, and their testimony recorded, so that the general character of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” may be vindicated, for the sake of truth and humanity.

That “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” should be so eagerly sought after and read, both in America and England, and produce the profound sensation it has, is the greatest compliment the age could pay to itself. All have contributed to give the book an enthusiastic reception; cheap editions and dear editions have followed each other with unexampled rapidity amongst us. Publishers of classical literature and publishers of trashy periodicals have sent forth editions of the book. Half-a-guinea editions and sixpenny editions have met with a rapid sale. And the most cheering fact of all is, that low publishers, who have hitherto only sent forth desolating streams of reading to the poorest classes of the community, have recently vied with each other in sending forth cheap editions of this wondrous work, and thereby showing that there was higher power of appreciation in the nation’s heart than they were aware of, and that a poisoned cheap literature has only flourished in the absence of something sweeter and purer. Mrs. Stowe’s work has not only sent vibrations along the chords of England’s universal heart, but it has already familiarized large portions of our population with a story tender in pathos, pure in sentiment, and elevating in aim. Whatever may be the evils which fester in the midst of our dirty alleys and neglected homes, it is encouraging and full of hope to know that there is a heart ready to beat in unison with the good and the pure, among the lowest and most neglected of our population. Well may the benevolent and the philanthropic be grateful to Mrs. Stowe for what she has already done in England! She has touched the hidden cells of feeling of many a degraded outcast, and awoke in him that latent and moral life which exists, and which is inextinguishable in every heart, however degraded. Though England is renowned for its churches and its Bibles, it is well known that untold numbers of its population know nothing of Christianity and its power to save. And for years past praise-worthy exertions have been made by the Established Church, and other Christian communities, to diffuse the blessings of the Gospel among the most ignorant and wretched; but unfortunately but little practical good has hitherto resulted therefrom. Perhaps the means which have been used were and are unequal to the task to be performed. But “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” will do, to a great extent, what sermons and tracts could not accomplish. It will be read or listened to by the lowest; and will, by virtue of its peculiar excellence, soften, and subdue, and purify. And many will see the workings and development of vital Christianity, as exhibited in the character of Uncle Tom, and the incarnate purity of the beautiful Eva, who would have no conception of such things by exhortations and tracts. Consequently, whether “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” does its work in America or not, it is already doing a work here which no agency before accomplished.

As for “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” being read by almost everybody everywhere, and not to a greater or less extent answer its purpose, is unreasonable and absurd. It is as well to say, that the flowery breath of spring awakens no cheerfulness, or the voluptuous swell of music yields no pleasure. The Pure and the Beautiful must, by virtue of their intrinsic excellence, influence for good all who are brought within their charmed circle.

There is something in the instantaneous effect produced by “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” approaching the sublime. A gentle woman moves her pen, and stirs races. She speaks, and millions are charmed by her melodious accents.

Clay, the modern disciple of Compromise, has frequently lashed audiences into a storm by his eloquence; and Webster, who was heaven-born, but slavery-corrupted, has frequently spoken ponderous words to a listening Senate; but their voices awoke no echoes in the universal heart—sent no electric currents through the great arteries of public opinion like “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” It will be seen, by-and-bye, that this gentle woman will do more to uproot slavery, than conventions and associations, and premature legislative action. She will do so by creating around Slavery an atmosphere of sentiment too pure for so vile a thing to live in. Has she not already upheaved a tide of feeling in her own country? And has not her book carried with it in this country, publishers, readers, newspapers, lecturers, theatres, and public opinion. And back a wave of that public opinion, charged with mingled sympathy and indignation, has gone to America, to add to the volume, of influence directed against slavery there.

The unbounded success of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” intimates the growth of an important element of moral power in those modern days. It shows what woman can do, and indicates what she is destined to do for the elevation of the race. It has been said and sung, “that they who rock the cradle rule the world"—meaning thereby that woman wields an immense power in forming the minds and training the characters of the world’s most illustrious sons. And it is so, and ever has been. The sages and heroes of the earth, have in their proudest moments of triumph and glory, principally attributed their success to the moral influence of their mothers. This must have been so, by the relationship necessarily existing between mother and child. But during the last few years, woman has been exerting another influence on the world. This she has been doing through the medium of that mightiest of all agencies—Literature. The age of Books and Newspapers has yet to come. Literature, though now mightier than the Pulpit and the Platform, and much mightier than both combined, grows in importance and power daily, and will continue to grow as the volume of years increase. And it is through this Literature that woman is destined to exert her potent strength in moulding the character and directing the destinies of man. To do this, it is not necessary that she should pour out high-sounding periods, but paint life as she sees and feels it; to speak, it may be, in monosyllables—but in syllables pregnant and vitalised with the essence of her soul, and then she will see, and the world will acknowledge her transcendant ability. The most powerful things are the most simple and silent. How silent is sunlight—and yet how powerful. Equally silent and equally powerful, in the moral world, is the sunlight of woman’s life and genius, when directed through the atmosphere of literature. A notable instance is this “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” It is a simple story about simple people. There is no king, or noble lord, or pompous baronet, figuring in its pages. Its heroes and heroines are not taken from courtly circles. The pride and pomp of fashionable life, and the gorgeous display of fashionable aristocratic circles, and all the other gilded machinery, which are the staple materials of ordinary novels, are scarcely alluded to in Mrs. Stowe’s work. No: the title of her book is “Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life among the Lowly,"—a title evidently too plebeian for British publishers, as we have not seen it adopted by any of them. Instead of parading before us the externally great, and the accidentally aristocratic, she induces us to walk with her in the midst of the most degraded of the human race—of men and women kept in servile bondage and shameful ignorance. She talks to us of their sorrows and sufferings, of their vices and virtues, of their wrongs and rights; and she talks in so simple a strain, that she enlists our most powerful sympathies in their behalf. She does it in a way that none but a woman could do. Mary Howitt, Mrs. S. C. Hall, George Sand, Mrs. Child, Eliza Cook, the author of “Jane Eyre,” and other living female writers, have given the world beautiful and captivating books—books distinguished as much for mental ability, as the moral purpose which pervades them. But that cluster of geniuses must now acknowledge another, and a greater star than any amongst their number. No one more triumphantly vindicates the significance of literature than Mrs. Stowe, as no one before has so effectively used it.

J. P. E.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS.

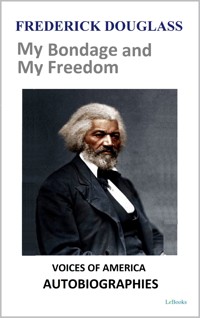

THE MOST REMARKABLE FUGITIVE SLAVE, and one of the most remarkable men in America, is Frederick Douglass. He possesses powers of mind and oratorical ability which would render him popular anywhere. He is one of the most eloquent speakers living, and he can wield his pen with as much effect as he can his tongue. His intense energy of character and moral bravery are acknowledged by all. His integrity and dignity of life and actions have long stamped him as one of the most extraordinary citizens of the United States. “If there is a man on earth,” says Dr. Campbell “he is a man.” To give our readers an idea of what this man was a little after he escaped from slavery, and to sharpen their curiosity to know what they can of his previous perilous and romantic life, we cannot do better than give a few passages from an address, delivered by W. Lloyd Garrison, in Boston, in 1845. “In the month of August, 1841,” says he, “I attended an anti-slavery convention in Nantucket, at which it was my happiness to become acquainted with Frederick Douglass. He was a stranger to nearly every member of this body, but having recently made his escape from the southern house of bondage, and feeling his curiosity excited to ascertain the principles and measures of the abolitionists—of whom he had heard a somewhat vague description while he was a slave—he was induced to give his attendance on the occasion alluded to, though at that time a resident in New Bedford.

“Fortunate, most fortunate occurrence! fortunate for the millions of his manacled brethren yet panting for deliverance from their awful thraldom! fortunate for the cause of negro emancipation and of universal liberty! fortunate for the land of his birth, which he has done much to save and bless! fortunate for the large circle of friends and acquaintances whose sympathy and affection he has strongly secured by the many sufferings he has endured; by his virtuous traits of character, by his ever abiding remembrances of those who are in bonds, as being bound with him! fortunate for the multitudes in various parts of our republic whose minds he has enlightened on the subject of negro slavery, and who have been melted to tears by his pathos, or roused to virtuous indignation by his stirring eloquence against the enslavers of men! fortunate for himself, as it at once brought him into the field of public usefulness, ‘gave the assurance of a MAN,’ quickened the slumbering energies of his soul and consecrated him to the great work of breaking the rod of the oppressor and letting the oppressed go free.

“I shall never forget his first speech at the convention; the extraordinary emotion it excited in my own mind, the powerful impression it created upon a crowded auditory, completely taken by surprise; the applause which followed from the beginning to the end of his felicitous remarks. I think I never hated slavery so intensely as at that moment; certainly my perception of the enormous outrage which is inflicted by it on the godlike nature of its victims, was rendered far more clear than ever. There stood one, in physical proportion and stature commanding and erect, in natural eloquence a prodigy, in soul manifestly ‘created but a little lower than the angles,’ yet a slave, aye, a fugitive slave, trembling for his safety, hardly daring to believe that on the American soil, a single white person could be found who would befriend him at all hazards, for the love of God and humanity. Capable of high attainments as an intellectual and moral being, needing nothing but a comparatively small amount of cultivation to make him an ornament to society and a blessing to his race—by the law of the land, by the voice of the people, by the terms of the slave code, he was only a piece of property, a beast of burden, a chattel personal, nevertheless!

“A beloved friend from New Bedford prevailed on Mr. Douglass to address the convention. He came forward to the platform with a hesitancy and embarrassment, necessarily the attendants of a sensitive mind in such a novel position. After apologising for his ignorance, and reminding the audience that slavery was a poor school for the human intellect and heart, he proceeded to narrate some of the facts in his own history as a slave, and in the course of his speech gave utterance to many noble and thrilling reflections. As soon as he had taken, his seat, filled with hope and admiration, I rose, and declared that Patrick Henry, of revolutionary fame, never made a speech more eloquent in the cause of liberty, than the one we had just listened to from the lips of that hunted fugitive. So I believed at that time—such is my belief how: I reminded the audience of the peril which surrounded this self-emancipated young man at the North, even in Massachusetts, on the soil of the Pilgrim Fathers, among the descendants of revolutionary sires; and I appealed to them, whether they would ever allow him to be carried back into slavery, law or no law, constitution or no constitution. Their response was unanimous, and in thunder-tones, ‘No!’ ‘Will you succour and protect him as a brother-man—a resident of the old Bay State?’ ‘YES!’ shouted the whole mass, with an energy so startling, that the ruthless tyrants south of Mason and Dixon’s line, might almost have heard the mighty burst of feeling, and recognised it as the pledge of an invincible determination on the part of those who gave it, never to betray him that wanders, but to hide the outcast, and firmly to abide the consequences.”

Frederick Douglass was born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in the county of Talbot, Maryland. But when he was born no one knows. Slaves never know when they were born, and are as ignorant of such times as horses. Frederick Douglass says he never met with a slave who knew how old he was, or could tell his birthday. When one jockey asks another, in this country, how old may be the horse which is about to be sold, the answer is, “three or four years last fall.” It is precisely in this way that the ages of slaves are estimated in America. And this one fact speaks volumes of the real state and degradation of the slave there.

Frederick Douglass says, that a want of information concerning his own age when he was a boy, was a source of great unhappiness to him. White boys could tell their ages, and be felt uneasy and degraded that he could not. The nearest guess which he is now enabled to give of his ago is, that he supposes he was born some time during the year 1828.

His father was a white man, and rumour went so far as to say that his father was his master. This is not at all unlikely, as it frequently happens, in the slave-holding states, that the father and the master are one. Frederick was separated from his mother while he was an infant. It was a custom in that part of Maryland to part mothers from their children at a very early age. This no doubt, is done to hinder the development of the child’s affection towards the mother, and to blunt and destroy the natural affection of the mother for the child. He never saw his mother more than a few times in his life. What need is there for any imagination to invent ideal disadvantages of slavery, when this one fact is acknowledged? The most tender and the strongest feeling in the human heart is that of a mother’s love for her offspring. It is a feeling as strong, yea, even stronger than life itself—a feeling from which the mother derives unutterable joy, and the child immeasurable advantage. But this of all other feelings is trodden under foot and spurned at in America. But poor slave as Douglass mother was, the infamous exactions imposed upon her, did not crush every spark of maternal love in her breast. He says he never remembers seeing his mother by daylight. When she saw him it was at night time. But she died when he was seven years of age; but as he never enjoyed much of her soothing presence he did not probably feel the loss very poignantly.

Instead of being a privilege to have one’s master for a father, it is a great disadvantage to the poor slave. This arises from the jealousy which the young mulatto excites in the breast of the master’s wife. Douglass says, “the master is frequently compelled to sell this class of his slaves, out of deference to the feelings of his white wife. And cruel as the deed may appear, for a man to sell his own children to human fleshmongers, it is often the dictate of humanity for him to do so; for unless he does this, he must not only whip them himself, but must stand by and see one white son tie up his brother, of but a few shades darker complexion than himself, and ply the gory lash to his naked back.”

One of Douglass masters was called Anthony, and though a cruel man himself, he had an overseer more cruel still. The overseer’s name was Plummer, who was a miserable drunkard, a profane swearer, and a savage monster. This man was hardened by a long life of slave-holding. He even took pleasure in whipping a slave. Douglas says, “I have often been awakened at dawn of day by the most heart-rending shrieks of an aunt of mine, whom he used to tie up to a joist, and whip upon her naked back till she was literally covered with blood. No words, no tears, from his gory victim, seemed to move his iron heart from its bloody purpose. The louder she screamed, the harder he whipped; and where the blood ran fastest, there he whipped; and where the blood ran fastest, there he whipped longest.” Here is a statement recorded by an eye-witness, which no doubt, if related by Mrs. Stowe in her “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” would have excited the indignation of the “Times,” for its “stimulating” character. The same authority may doubt it now. But why doubt it? Does not familiarity breed contempt? Can we expect grapes from thorns and figs from thistles? Is not the slaveholder himself demoralized by the inhuman system he sustains? And if so, is it unreasonable to suppose that overseers should be inhuman? And if inhuman, is it net unreasonable to suppose that such statements as the above are exaggerations? In fact, such things cannot easily be exaggerated; and well might Douglass say, “It was a most terrible spectacle. I wish I could commit to paper the feelings with which I beheld it.”

Douglass soon got under the tender mercies of another overseer, whose name was Severe, who was rightly named and, who soon died. He was followed by another whose name was Hopkins, who remained but a short time, because he was not sufficiently severe. Mr. Hopkins was succeeded by Mr. Austin Gore, “a man possessing in an eminent degree all those traits of character indispensable to what is called a first-rate overseer.” This Mr. Gore was a grave man, and though a young man, he indulged in no jokes, said no funny words, seldom smiled. His acts were in perfect keeping with his words. Overseers will sometimes indulge in a witty word, even with the slaves; not so with this Mr. Gore. He was “dressed in a little brief authority,” and must have made “e’en angels weep,” and poor slaves at the same time. “He spoke but to command, and commanded but to be obeyed; he dealt sparingly with his words, and bountifully with his whip; never using the former, while the latter would answer as well. When he whipped, he did so from a sense of duty, and feared no consequences. He did nothing reluctantly, no matter how disagreeable; always at his post, never inconsistent. He never promised but to fulfil. He was a man of the most inflexible firmness and stone-like coolness. He was of all overseers most dreaded by the slaves. His presence was painful, his eye flashed confusion, and seldom was his sharp shrill voice heard without producing horror and trembling in their hearts.”

Such is a passing sketch of a consistent man, whose barbarity was only equalled by the consummate coolness with which he committed the grossest and most savage deeds. He once undertook to whip a slave of the name of Demby. He had given Demby but a few stripes, when, to get rid of the scourging, he ran and plunged into a creek, and stood there at the depth of his shoulders, refusing to come out.

“Gore told him that he would give him three calls, and that if he did not come out at the third call, he would shoot him. The first call was given. Demby made no response, but stood his ground. The second and third calls were made with the same result. Mr. Gore then, without consultation or deliberation by any one, not even giving poor Demby an additional call, raised his musket to his shoulder, taking deadly aim at his standing victim, and in an instant poor Demby was no more, his mangled body sank out of sight, and blood and brains marked the water where he had stood.

“A thrill of horror flashed through every soul upon the plantation, excepting that of Mr. Gore. He was asked by Colonel Lloyd, why he resorted to this extraordinary expedient? His reply was (as well as I remember) that Demby had become unmanageable—that he was setting a bad example to the other slaves—one which, if suffered to pass without some such demonstration on his part, would finally lead to the total subversion of all rule and order upon the plantation. He argued, that if one slave refused to be corrected, and escaped with his life, the other slaves would soon copy the example; the results of which would be the freedom of the blacks, and the enslavement of the whites. Mr. Gore’s defence was satisfactory. He was continued in his station as overseer upon the same plantation. His fame as an overseer went abroad. His horrid crime was not even submitted to judicial investigation. It was committed in the presence of slaves, and they of course could neither institute a suit, nor testify against him; and thus the guilty perpetrator of one of the bloodiest and most foul murders goes unvisited by justice, and uncensured by the community in which he lives.” In order to substantiate the fact, and to leave no doubt on the reader’s mind, Mr. Douglass gives all its particulars. He says, “Mr. Gore lived in St. Michael’s, Talbot county, Maryland, when I left there; and if he is still alive, he very probably lives there now; and if so, he is now, as he was then, as highly esteemed and as much respected as though his guilty soul had not been stained with his brother’s blood.

“I speak advisedly when I say that killing a slave, or any coloured person, in Talbot county, Maryland, is not accounted as a crime, either by the courts or the community. Mr. Thomas Lanman, of St. Michael’s, killed two slaves, one of them he killed with a hatchet, by knocking his brains out. He used to boast of the commission of the awful deed. I have heard him do so, laughingly, saying, among other things, that he was the only benefactor of the country in the company, and that when others had done as much as he had done, we should be relieved of the d–-d n–ers.”

Mr. Douglass goes on to say “the wife of Mr. Giles Hicks, living but a short distance from where I used to live, murdered my wife’s cousin, a young girl between fifteen and sixteen years of age, mangling her person in the most horrible manner, breaking her nose and breastbone with a stick, so that the poor girl expired in a few hours afterwards. She was immediately buried, but had only been in her untimely grave a few hours, before she was taken up and examined by the coroner, who decided that she had come to her death by beating. The offence for which this girl was thus murdered was this—She had been set that night to mind Mrs. Hicks’ baby, and during the night she fell asleep, and the baby cried. The girl having lost her rest for several nights previous, did not hear the crying. They were both in the room with Mrs. Hicks. Mrs. Hicks finding the girl slow to move, jumped from her bed, seized an oak stick from the fire-place, and with it broke the girl’s nose and breastbone, and thus ended her life. I will not say that this most horrid murder produced no sensation in the community. It did produce a sensation, but not enough to bring the murderess to punishment. There was a warrant issued for her arrest, but it was not served. Thus she escaped not only punishment, but even the pain of being arraigned before a court for her horrid crime.

“Whilst I am detailing bloody deeds which took place during my stay on Colonel Lloyd’s plantation, I will briefly narrate another, which occurred about the same time as the murder of Demby by Mr. Gore.

“Colonel Lloyd’s slaves were in the habit of spending a part of their nights and Sundays in fishing for oysters, and in this way made up the deficiency of their scanty allowance. An old man, belonging to Colonel Lloyd, while thus engaged, happened to get beyond the limits of his master’s plantation, and on the premises of Beal Bondly. At this trespass Mr. Bondly took offence, and, with his musket, came down to the shore, and blew its deadly contents into the poor old man.

“Mr. Bondly came over to see Colonel Lloyd the next day, whether to pay him for his property, or to justify himself in what he had done, I know not; at any rate, this whole fiendish transaction was soon hushed up. There was little said about it, and nothing done. It was a common saying, even among little white boys, that it was worth a half cent to kill a n–er, and a half cent to bury one.”

Had Mrs. Stowe detailed such circumstances as these, it would have been said that her “pictures were too stimulating,” and her “delineations too highly coloured and exaggerated,” and that, consequently, she would defeat her purposes, and that the slave’s fetters would be fastened still closer on her account. But we have here detailed facts not fictions; and these facts are given by an eye-witness, whose statements can be relied on, as much as those of any pro-slavery man in America.

Mr. Horace Greeley, a man of great mental endowments, and high moral respectability, said, in the “New York Tribune,” (a paper which circulates more copies daily than the “Times") a little after Frederick Douglass’ life was published, “We highly prize all evidence of this kind, and it is becoming more abundant. Douglass seems very just and temperate. We feel that his view, even of those who have injured him most, may be relied on. He knows how ‘to allow for motives and influences.’ “ Such is the endorsement of Mr. Horace Greeley’s opinion of the truths contained in Frederick Douglass’ narrative. Another authority, as high as that of Mr. Greeley’s—Mr. Wendell Phillips, says, in a letter to Douglass, “In reading your life, no one can say that you have unfairly picked out some rare specimens of cruelty. We know that the bitter drops, which even you have drained from the cup, are no incidental aggravations, no individual ills, but such as much mingle always and necessarily in the lot of every slave. They are the essential ingredients, not the occasional results of the system.” Mr. Lloyd Garrison, another man who is as much celebrated for his virtuous character, as for his intense hatred of the “peculiar institution,” which it is the peculiar glory of America to possess, says, in the preface to Douglass’ life, that every word it contains may be relied on for its truthfulness. The men whose names I have here mentioned are as respectable as any of the writers in the “Times” newspaper. That paper has impunged the character of Mrs. Stowe’s book, because it is exaggerated, and yet that book does not contain instances more diabolical than those related by Douglass. The most barbarous incident detailed in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” is the death of Uncle Tom himself, and the means used to bring it about. He was flogged to death and his murderer was not arraigned before a court of justice. If he had been, there was no evidence to prove the fact, as the evidence of a slave is no evidence in the Southern States. This is quite consistent. Take away from a man over himself, ignore his individuality and humanity, and then take his evidence on oath before a court of justice, would be folly. It would be admitting him a man in the one instance and not in the other.

It so happens that where barbarous transactions take place, very frequently there is no white man near, and certainly no friendly white man. And it is quite evident, and quite reasonable to believe, that where one murder gets circulated, ten or more are heard nothing of; and it is not for a moment unreasonable to suppose, that in those great cotton plantations of the South, where the slave is held in such low estimation as a man, and where cruel hard-hearted overseers are permitted to have uncontrolled sway over him, that he should frequently fall a victim to the passion or caprice of those above him. We have just recorded five instances which occurred within a brief period, in a comparatively small portion of the slave-holding states. And as Mr. Douglass has given the names of the places, and the parties, without meeting with any authentic contradiction, we are bound to believe what he says, and in believing it, express our deepest detestation of slavery, and condemnation of slave-holders. As a confirmation of Mr. Douglass’ evidence, we will give an extract from a Baltimore paper. The “Baltimore American,” of March 17, 1845, contains the following—

“SHOOTING A SLAVE.—We learn upon the authority of a letter from Charles county, Maryland, received by a gentleman of this city, that a young man, named Matthews, a nephew of General Matthews, and whose father, it is believed, holds an office at Washington, killed one of his slaves upon his father’s farm, by shooting him. The letter states that young Matthews had been in charge of the farm; that he gave an order to the servant, which was disobeyed, when he proceeded to the house, obtained a gun, and, returning, shot the servant. He immediately,” the letter continues, “fled to his father’s residence, where he still continues unmolested.” We give this extract as it is taken from a paper printed near where Douglass formerly lived.

After the above, we think, pardonable digression, we return to the early career of Douglass. He did not remain long on Colonel Lloyd’s plantation, and while there, was not, on the whole, treated harshly. He was sufficiently fortunate to become a bit of a favourite of Colonel Lloyd’s son Daniel, and was employed in going with him on shooting excursions, and finding the birds after they were shot, or in running errands for Daniel’s sisters. His young master would not allow older boys to impose on his “little n–er,” and would even go so far as to divide his cakes with him. Douglass says, “I was seldom whipped by my old master, and suffered little from anything else than hunger and cold. I suffered much from hunger, but much more from cold. The hottest summer, and coldest winter, I was kept almost naked—no shoes, no stockings, no jacket, no trousers, nothing but a coarse torn linen shirt, reaching only to my knees. I had no bed. I must have perished with cold, but that during the coldest nights, I used to steal a bag which was used for carrying corn to the mill. I would crawl into this bag, and then sleep on the cold, damp clay floor, with my head in, and feet out. My feet have been so cracked with the frost, that the pen with which I am writing, might be laid in the gashes. We were not regularly allowanced. Our food was coarse corn-meal, boiled, called mush. It was put into a large wooden tray or trough, and set down upon the ground. The children were then called like so many pigs, and like so many pigs they would come and devour the mush,—some with oyster-shells, others with pieces of shingle, some with naked hands, and none with spoons. He that ate fastest got most; he that was strongest secured the best place, and few left the trough satisfied.”

Douglass was about eight years old when he left Colonel Lloyd’s plantation to go to Baltimore, to live with Mr. Hugh Auld. When the information reached him that he was to go, he danced for joy; and why should he not? He had no home. His mother was dead, and there was nothing particular in Colonel Lloyd’s plantation to attract him. He had three days to prepare previous to leaving for Baltimore; and these three days were spent in “washing off the plantation scurf, not so much because he wished to wash, but because Mrs. Lucretia had told him that he must get all the dead skin off his feet and knees before he could go to Baltimore, for the people there were very cleanly.” Besides, she was going to give him a pair of trousers. The thought of owning a pair of trousers was great indeed. He says, “It was almost a sufficient motive not only to make me take off what would be called by pig-drovers the mange, but the skin itself. I went at it in good earnest, working for the first time with the hope of reward.”

When he got to Baltimore, he found that he had to take care of the little son of Mr. Auld. Here he saw what he had never seen before—a white face beaming upon him with the most kindly emotions—the face of his mistress, Mrs. Sophia Auld. It was a strange sight to him, brightening up his pathway with the light of happiness. He ever afterwards attributed his removal from Colonel Lloyd’s plantation as a manifestation of Providence, as it “opened the gateway to all his subsequent prosperity.”

His new mistress proved all she appeared, or at least for some time. “Her face was made of heavenly smiles, and her voice of tranquil music.” She taught Douglass the A. B. C., and to read words of three or four letters. But just at this part of his progress, her husband found out what was going on, and at once forbade Mrs. Auld to instruct him any further telling her that it was not only unlawful, but unsafe, to teach a slave to read. He said, if you give a n–er an inch, he will take an ell. A n–er should know nothing, but obey his master. Learning would spoil the best n–er in the world, and he was right. For the very small amount of instruction the boy had received from his mistress awoke in him an unquenchable desire to know more. The words of his master sank deep into his heart, and stirred emotions which before slumbered. They were to him a new and special revelation, explaining dark and mysterious things, with which his youthful understanding had struggled. He long entertained doubts about the relative positions of the white man and the black man, and could not imagine why the one should continue the slave of the other. But when he heard that learning would spoil the best n–er in existence, he saw in what consisted the controlling power of the white man over the slave. From that moment he saw the pathway from slavery to freedom. Though conscious of the difficulty of learning without a teacher, he set out with a high hope and a fixed purpose to learn to read at whatever cost of labour. “All the heaven of great desire” was lit within him. And now began his “pursuit of knowledge under difficulties.”

The plan which he adopted, and the one by which he was most successful, was that of making friends of all the little white boys he met in the streets. As many of those as he could he converted into teachers, and used all kinds of manoeuvres to entice them to teach him. When he was sent on errands he carried his little book with him, and by going one part of the way quickly, he found time to get a lesson before he returned. He used to carry crusts of bread with him, with which he would tempt the little hungry urchins to assist him to get the more valuable bread of knowledge, for which he was still more hungry. His master and mistress were now suspicious that he was learning to read, and watched him secretly, and threw every possible impediment in his way. But it was now too late. The first step was taken, and his mistress, in teaching him the alphabet, had given him the inch, by which he would take the ell. Little did she know what she was doing at the time. She was sending the first stray beam of sunlight into a soul that had wrapped up within it mighty powers. She was warning into real intellectual life an intellectual giant—a giant who would, in a very few years vindicate his equality with the greatest man in America. She was unknowingly instructing a boy who would soon, as a man, send his fame over the world—who would speak potent words and perform great deeds for humanity—a man who, had he a lighter-coloured skin, would, perhaps, soon have filled the President’s chair itself. It is not even unlikely now that Frederick Douglass, though a coloured man, will, one day, be the President of the United States. For slavery cannot remain much longer in that country. In spite of all that Webster and all the compromise men have done, this question of questions must get uppermost, whether the integrity of the Union be threatened thereby or not. If slavery be abolished during Frederick Douglass’ lifetime, then will he stand a good chance of being elected President. I remember hearing him when he came to this country some time since. He spoke at a large London meeting, and I never heard eloquence so-electrical before. I never saw an English audience so excited as it was under his magic words. He would, at one moment, lash the audience into a storm, and in another moment make it as tranquil as a lake without a ripple. When he sat down. Dr. Campbell, the Editor of the “British Banner,” got up and said, “That if he were a few years younger, he would have gone around the world to listen to that speech, rather than not have heard it.” And there was not a young man in that vast assembly who would not have followed the doctor; This extraordinary speech will form an Appendix to this volume. We give it verbatim, for two reasons, namely, to show what a poor fugitive slave could do in the greatest city of the world a few years after his self-emancipation, and secondly, to familiarize the British reader with the horrors of the slave system in America. Whoever reads this speech will say, that if it does not equal the finest efforts of Burke, whom the boy Douglass so much admired, that the man Douglass, with English cultivation and advantages, would successfully rival the great English orator. Such was the influence of Douglass’ thrilling eloquence. And this man, a few years before, was a slave—a poor slave, in a country which boasts of its independence, its liberty, and its greatness! Well might Dr. Channing say “We are keeping in bondage one of the finest races living.” O, America, so sure as a God liveth, the day of retribution must come! So vast a crime cannot be perpetrated without punishment.

Frederick Douglass had not long continued reading before he saw and felt his degradation. Just about this time, and he was only about twelve years of age, he got hold of a book entitle “The Columbian Orator,” Among other stirring things in this book he with with one of Sheridan’s mighty speeches on behalf of Catholic Emancipation. This gave tongue to interesting thoughts of his own soul, which had flashed through it, and died away for want of utterance. As he read and contemplated, that very discontent which was alluded to by his master, came “to torment and sting his soul with unutterable anguish.” He began to feel that reading was a curse rather than a blessing to him. It opened his eyes to the horrible pit in which he was plunged. He preferred the condition of the meanest reptile to his own. He says, “anything, no matter what, to get rid of thinking. It was everlasting thinking of my condition that tormented me. There was no getting rid of it; it was pressed upon me by every object within sight or hearing; animate or inanimate. The silver trump of freedom had roused my soul to eternal wakefulness. Freedom now appeared, to disappear no more for ever. It was heard in every sound, and seen in everything. It was ever present to torment me with the sense of my wretched condition. I saw nothing without seeing it; I heard nothing without hearing it; and felt nothing without feeling it. It looked from every star, it smiled-in every calm, breathed in every wind, and moved in every storm.”

The manner in which the future reformer and orator learnt to write is worth recording. The idea of how he might do so was suggested in a ship-yard. Here he frequently saw the ship-carpenters, after hewing and getting a piece of timber ready for use, write on it the name of that part of the ship for which it was intended. When a piece of timber was intended for the larboard side, it would be marked “L;” when a piece was for the starboard side, it would be marked “S,” and so on. In this way he learnt to write these and other letters, and immediately, in his way, commenced copying them. After that, when he met with any boy whom he knew could write, he would tell him he could write as well as him. He would be answered with “I don’t believe you; let me see you try it.” He would then make the letters which he had been so fortunate as to learn, and ask the boy to beat that. In this way he got a great many writing lessons, which it would be impossible for him to get in any other way. During this time his copy book was the board-fence, the brick wall and pavement, and his pen and ink a lump of chalk. He says: “By this time my little master Thomas had gone to school, and learned how to write, and had written over a number of copy-books. These had been brought home, and shown to some of our near neighbours and then thrown aside. My mistress used to go to class-meeting every Monday afternoon, and leave me to take care of the house. When left thus I used to spend the time in writing on the spaces left in Master Thomas’s copy-book, crossing what he had written. I continued to do-this until I could write a hand very similar to that of Master Thomas. Thus, after a long tedious effort, I finally succeeded in learning to write.”

Soon after this Douglass master died, and he, the slave, was valued with the other property. The stock on the estate was all valued together, men and women, old and young, married and single horses, sheep, and swine. Horses and men, cattle and women, pigs and children, were all held in the same rank in the scale of being by the valuer, and were all subjected to the same narrow examination. Silvery-headed age and sprightly youth, maids and matrons, underwent the same indelicate examination. Poignantly must the young slave have felt the degradation of his situation, when he saw himself held in the same estimation as the brutes. But such is slavery.

It fell to the lot of Douglass to be apportioned to Mrs. Lucretia, a daughter of his late master. In this he was fortunate, as he might have fallen to the portion of Master Andrew, who was a most cruel monster. “A man who,” says Douglass, “but a few days before, to give me a sample of his bloody disposition, took my little brother by the throat, threw him on the ground, and with the heel of his boot stamped upon his head, till the blood gushed from his nose and ears.” Very soon after this division of property, Mrs. Lucretia died; and a short time after her death, Master Andrew died. Now all the property of his late master fell into the hands of strangers. Not a slave was left free, not even Douglass’ old grandmother, who had been a source of wealth to his late master. “If any one thing,” says Douglass, “in my experience, more than another, served to deepen my conviction of the infernal character of slavery, and to fill me with unutterable loathing of slaveholders, it was their base ingratitude to my poor old grandmother. She had served my old master faithfully from youth to old age. She had been the source of all his wealth; she had peopled his plantation with slaves; she had become a great-grandmother in his service. She had rocked him in infancy, attended him in childhood, served him through life, and at his death wiped from his icy brow the cold death-sweat, and closed his eyes for ever. She was nevertheless left a slave—a slave for life—a slave in the hands of strangers; and in their hands she saw her children, her grandchildren, and her great-grandchildren divided, like so many sheep, without being gratified with the small privilege of a single word as to their or her own destiny. And to cap the climax of their base ingratitude and fiendish barbarity, my grandmother, who was now very old, having outlived my old master and all his children, having seen the beginning and end of all of them, and her present owners finding she was of but little value, her frame already racked with the pains of old age, and complete helplessness fast stealing over her once active limbs, they took her to the woods, built her a little hut, put up a little mud chimney, and then made her welcome to the privilege of supporting herself there in perfect loneliness; thus virtually turning her out to die! If my poor old grandmother now lives, she lives to suffer in utter loneliness; she lives to remember and mourn over the loss of her children, the loss of grandchildren, and the loss of great-grandchildren. The hearth is desolate. The children, the unconscious children, who once sang and danced in her presence, are gone. She gropes her way, in the darkness of age, for a drink of water. Instead of the voices of her children, she hears by day the moans of the dove, and by night the screams of the hideous owl. The grave is at the door. And now, when weighed down by the pains and aches of old age, when the head inclines to the feet, when the beginning and ending of human existence meet, and helpless infancy and painful old age combine together—at this time, this most needful time, the time for the exercise of that tenderness and affection which children only can exercise towards a declining parent—my poor old grandmother, the devoted mother of twelve children, is left all alone, in yonder little hut, before a few dim embers. She stands—she sits—she staggers—she falls—she groans—she dies—and there are none of her children or grandchildren present, to wipe from her wrinkled brow the cold sweat of death, or to place beneath the sod her fallen remains. Will not a righteous God visit for these things?”

Douglass had to change masters several times. In 1832, he left Baltimore, and went and lived with Mr. Thomas Auld, at St. Michael’s. This Mr. Auld was a mean man. He kept his slaves without sufficient food. And not to give a slave enough to eat is regarded as the most aggravated development of meanness, even among slaveholders. One of the most extraordinary moral phenomenon among slaveholders is, that those who profess to be religious are frequently the most cruel and mean. In August, 1832, this Mr. Auld attended a Methodist camp meeting, “and there experienced religion.” It was thought he would now alter for the better. But if he altered at all, he altered for the worse. For, prior to his conversion, he relied upon his own depravity to shield and sustain him in his barbarity; but after his conversion he found religious sanction and support for his slaveholding cruelty. He made the greatest pretension to piety. He prayed morning, noon and night. His activity at revivals was very great, and he proved himself an instrument in the hands of the church in converting many souls. His house was the preachers’ home. But while he stuffed the preachers, he starved his slaves. Such is one of the anomalies of human conduct, and it can only be explained on the principle that “familiarity breeds contempt.”