0,92 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Fleming Stone

- Sprache: Englisch

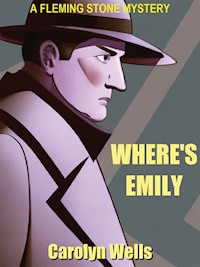

On the eve of her marriage to Rodney Sayre, Emily Duane disappears. She had left her Hillside Park home to visit the hospital but never arrived. Foul play is feared when Jim Pennington reports his wife Pauline, Emily’s best friend, also missing. Pennington says he left his wife at the ravine a short distance from Emily’s home. When he returned, she had vanished. Then Polly’s body is found in the ravine...but where is Emily? Fleming Stone investivates!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 347

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

WHERE’S EMILY? by Carolyn Wells

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

INTRODUCTION, by Karl Wurf

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

WHERE’S EMILY?by Carolyn Wells

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2023 by Wildside Press LLC.

Originally published in 1927.

Published by Wildside Press LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com | blackcatweekly.com

INTRODUCTION,by Karl Wurf

Carolyn Wells (1862- 1942) was an American writer of poetry and novels. She is best known these days as the author of the Fleming Stone mystery series which—according to Crime Fiction IV: A Comprehensive Bibliography, 1749–2000 (2003)—numbers 61 titles.

After finishing school, Wells worked as a librarian for the Rahway Library Association while beginning to publish. During the first ten years of her career, she concentrated on poetry, humor, and children’s books. Her first book, At the Sign of the Sphinx (1896), was a collection of literary charades. She followed up with The Jingle Book and The Story of Betty (1899), followed by Idle Idyls (1900), a book of verse. After 1900, Wells became a full-time writer, penning numerous novels and collections of poetry. All told, she wrote 170 books, as well as hundreds of shorter pieces.

According to her autobiography, The Rest of My Life (1937), she heard Anna Katherine Green’s mystery novel, That Affair Next Door (1897), being read aloud and was immediately captivated by it. Almost instantly, she pivoted her writing career to mysteries. Among the most famous, as previously mentioned, are the Fleming Stone books. Wells’s The Clue (1909) is on the Haycraft-Queen Cornerstone List of essential mysteries.

She was also the first to assembled annual collections devoted to the best short crime fiction of the previous year in the U.S., beginning with The Best American Mystery Stories of the Year (1931)—though a similar British series predates it by 2 years.

She died at the Flower Fifth Avenue Hospital in New York City.

THE FLEMING STONE SERIES

The Clue (1909)

The Gold Bag (1911)

A Chain of Evidence (1912)

The Maxwell Mystery (1913)

Anybody But Anne (1914)

The White Alley (1915)

The Curved Blades (1915)

The Mark of Cain (1917)

Vicky Van (1918)

The Diamond Pin (1919)

Raspberry Jam (1920)

The Mystery of the Sycamore (1921)

The Mystery Girl (1922)

Feathers Left Around (1923)

Spooky Hollow (1923)

The Furthest Fury (1924)

Prillilgirl (1924)

Anything But the Truth (1925)

The Daughter of the House (1925)

The Bronze Hand (1926)

The Red-Haired Girl (1926)

The Vanity Case (1926)

All at Sea (1927)

Where’s Emily (1927)

The Crime in the Crypt (1928)

The Tannahill Tangle (1928)

The Tapestry Room Murder (1928)

Triple Murder (1929)

The Doomed Five (1930)

The Ghosts’ High Noon (1930)

Horror House (1931)

The Umbrella Murder (1931)

Fuller’s Earth (1932)

The Roll-Top Desk Mystery (1932)

The Broken O (1933) (also published as Honeymoon Murder)

The Clue of the Eyelash (1933)

The Master Murderer (1933)

Eyes in the Wall (1934)

The Visiting Villain (1934)

The Beautiful Derelict (1935)

For Goodness’ Sake (1935)

The Wooden Indian (1935)

The Huddle (1936)

In the Tiger’s Cage (1936)

Money Musk (1936)

Murder in the Bookshop (1936)

The Mystery of the Tarn (1937)

The Radio Studio Murder (1937)

Gilt Edged Guilt (1938)

The Killer (1938)

The Missing Link (1938)

Calling All Suspects (1939)

Crime Tears On (1939)

The Importance of Being Murdered (1939)

Crime Incarnate (1940)

Devil’s Work (1940)

Murder On Parade (1940)

Murder Plus (1940)

The Black Night Murders (1941)

Murder at the Casino (1941)

Murder Will In (1942)

Who Killed Caldwell? (1942)

CHAPTER 1

PERSONALITY

“Where’s Emily?”

“Dunno, Aunt Judy. Shall I go a-hunting?”

“No, no, Rod. Betty—Nell—doesn’t anybody know where Emily is?”

“Did anybody ever know!”

“You see,” Aunt Judy whispered discreetly, “the minister’s here.”

“Oh, that! Well, tell him Emily’s gone walking with the Swami. That’ll give him one crowded hour of glorious life—”

“Leave all to me; I’ll take care of the cloth. What’s a best man for?”

Burton Lamb stepped to Aunt Judy’s side, and murmuring “lead me to him” left the room with her.

In a small reception room they found the Reverend Mr. Garner seated in a truly ecclesiastical attitude on the edge of a chair.

He was of an austere and ascetic type, and his fundamental beliefs were written plainly in his square, set jaw, and his snapping black eyes.

Aunt Judy had snapping black eyes, too, but of quite a different snap.

Lamb went through his part of the introduction with his usual nonchalant grace, and sat down sideways on a chair to see what he could do about it.

“Yes, Emily is not here for the moment,” he said, “and I’m wondering if I won’t do, instead. If it’s anything about the plans, you know—the arrangements—of course, as best man, I have it all at my finger ends—I mean at my wit’s end. You’ll be at the rehearsal this evening?”

“Yes—at six or so, is it not? But it is the service I have in mind, not the—er—social side of it. Emily is of the—the ultramodern set who have little care for the dignity or gravity of the sacrament.”

“Oh, I know what he’s getting at,” Aunt Judy exclaimed. “You are bothered because she means to omit the word ‘obey.’ I know—it worried me ’most to death at first, too. But she explained it to me—”

“Pardon me, it admits of no explanation, Mrs. Bell.”

“Yes, I thought so too, at first. But I’ve come round to Emily’s way of thinking and—”

“But her way of thinking cannot change the prayer book—”

“Now, look here, Mr. Garner,” Lamb began, in his pleasantly decisive way, “isn’t it a bit late for a discussion of this matter? The wedding is on Saturday, and today is Thursday. No amount of argument or debate on your part would change Emily’s mind in the least degree. Therefore, you will have to submit to her decision or refuse to perform the ceremony. In that case—pardon my plain speaking, but you see I am the best man, and it is my duty to attend to everything I possibly can that will save the bride and groom from any bit of worry or bother. So, again pardon my straightforwardness: if you do not wish to fall in with the ideas of Emily and Mr. Sayre, then I must be about the business of finding somebody who does.”

“I am told, too,” the irate dominie went on, “that Emily does not intend to take the name of Sayre, but will continue to be known as Emily Duane.”

“That is a matter entirely outside your jurisdiction, sir.” Even mild-mannered Burton Lamb was beginning to lose his patience. “That is the legal side of this affair, not the religious part of it.”

“Now, Mr. Garner,” Aunt Judy put in, and her black eyes snapped into his own, “I am older than you are, I was brought up as strait-laced and hide-bound as you were, but owing to the trend of the times and the ways of the world, and the dominance of the younger generation, I see clearly that the only thing to do is to let them have their way, which they will do, anyhow.”

The white, bobbed hair shook its pretty soft curls at him, the nearly double chin set itself in soft ridges, and Aunt Judy smoothed down her short skirt over her not invisible silk-clad knees, with an obvious submission to the trend of the times and the ways of the world.

The Reverend Garner looked at her.

“You naturally side with your niece,” he said coldly, “but I am told that Mr. Rodney Sayre is not at all in accordance with his bride’s views, and that he would much prefer the orthodox and time-honored ways.”

“That, too,” and Lamb spoke now with real asperity, “is outside your province, Mr. Garner. At a wedding, it is the bride who gives orders, who has her own way in every particular. I am glad Emily is not here to listen to you, for it would only rouse her anger and lead to unpleasantness. As I am, then, practically master of ceremonies, I ask you to decide now, at once, whether or not you will meet Miss Duane’s wishes in every particular. If not, there is no real reason why you should attend the rehearsal this evening. I daresay the—that is, Mr. Lal Singh—”

“Oh, hush!” exclaimed Aunt Judy, scandalized herself, now, “he is a Hindu!”

“Oh, I know, I know,” put in Mr. Garner. “He’s that Swami, or whatever he calls himself, who is attracting a lot of foolish fashionable women to his lectures, and who—”

“We really haven’t time now to discuss theosophy,” Lamb gently insisted. “Do you or do you not want to officiate at the wedding, Mr. Garner?”

“I wish I might see Miss Duane herself for a moment—”

“Well, you can’t, and it wouldn’t do you a bit of good,” declared Aunt Judy. “Oh, pshaw, Mr. Garner, don’t stir up trouble at this late date. Just do as our darling bride wants you to, or else say you won’t, and we can easily get another minister—and not a heathen, either.”

The Reverend Garner, being after all—or, perhaps, before all—human concluded he didn’t care to lose the pleasant fee which this same efficient best man would probably hand him, so he made the best of the situation, and took his leave, agreeing to do as Mrs. Bell had advised.

“Where’s Emily?” asked Aunt Judy, as she and Lamb returned to the lounge. “What’s the girl doing?”

“She was here,” Nell Harding informed, “but she flew off again. Went to take another look at her necklace, she said. We’re talking about personality. I say Emily has more of it than any one I ever knew.”

“Silly word,” put in Pete Gibby. “Doesn’t mean a thing. Everybody has personality of one sort or another—”

“It doesn’t mean that, dearie,” Betty Bailey kindly educated him. “It means, why, it means—”

“Go on—what does it mean?”

“Oh, just that you stand out, you know. You’re like a solitaire diamond and the others are like a cluster.”

“Not bad, Betty,” Sayre agreed. “Yes, Emily is like that—she—”

“Never mind, Signor Benedick, we have a dim idea of your opinion of Emily.”

“Have I personality?” asked Nell Harding, who was to be one of the bridesmaids.

“You bet you have!” said Lamb, who was madly in love with her.

“Have I?” cried Betty Bailey.

“Not a bit,” Pete Gibby told her. “You’re strictly impersonal. Aunt Judy here has more than all the rest of us put together.”

Mrs. Bell smiled absently, accustomed to their foolishness.

Though nominally in charge of the house and of her niece, she actually had no hand in managing either.

When Emily’s parents had both been killed in a motor accident, Mrs. Bell, as the only available relative, had come to Knollwood as a matter of course.

And as a matter of course, she was still there, but the direction of the establishment was entirely at the will or whim of imperious, efficient Emily, personification of personality and able exponent of the younger generation.

Not that Emily was a flapper. She was twenty-two, well educated, well mannered and a thorough-bred.

But impulsive and high-tempered, she needed a restraining hand now and then and there was none to stretch out to her.

She was sole heir to her father’s enormous fortune, which was judiciously attended to for her by able trustees.

She did whatever she chose and she had whatever she wanted.

In fact she lacked nothing but parental love and guidance, and this, some said, was lucky for the parents.

Not that Emily was wild or eccentric.

But she had little sense of moderation and once bent on a thing would achieve it at any cost.

And she had the elusive charm ambiguously termed personality.

With it, she could make almost any one bend to her will or grant her request.

It made her a favorite and a belle. She had hosts of friends and no enemies, unless some envious or jealous young people were to be counted.

Her home, the great and beautiful house her father had built up among the Ramapo Hills, was filled with everything that conduced to comfort or happiness, and Emily and Aunt Judy lived in the utmost peace and harmony.

School, travel, friends, social success, had all come to the girl in turn, and now she was about to marry Rodney Sayre and a house party was gathered for the wedding festivities.

Although at the time of her arrival in Emily’s home, Aunt Judy had been an old-fashioned, even provincial sort, her niece had changed all that.

She had ordained that Mrs. Bell should do at all times and in all things exactly as Emily dictated and not otherwise, that strict adherence to this plan of campaign would make for happiness and contentment, while any dereliction from such a path would lead straight to chaos and misery.

So clearly was this set forth and so emphatic was the insistence upon it that Mrs. Bell saw at once she must acquiesce or depart.

In her wisdom she chose the former course, continued in that course, and all went very well indeed.

For Emily was not a bit difficult to get along with if she had her Own way. And her way, though sometimes amazing and even incomprehensible, was never in line of any wrongdoing.

Her flapperhood was hoydenish but not reprehensible. Her love affairs were hectic and frequent, but short-lived. Her fads and hobbies, though often expensive, were harmless.

And if she was criticized by some of her neighbors, she was beloved by many more.

Neighbors were numerous, though not very near.

Hilldale Park was a gesture that followed the building of the Duane house, and the exclusive reservation contained now many beautiful estates that spread out from Emily’s home in all directions.

The whole region was more or less wild, and strictly kept so. Main motor roads there were, and some paved sidewalks, but there were also many places whose walks were footpaths through the woods or winding ways skirting ravines of picturesque beauty.

The dwellers were largely artists or lovers of the arts, most of them wealthy and most of them young or trying to keep so.

Fads were taken up, tried out and dropped in rapid succession. Philanthropies likewise, also charities.

A new hospital, but recently opened, was the pride of the community, and a new Hindu teacher, Swami Lal Singh, was the current excitement.

With her usual impulsiveness, Emily had thrown herself into this metaphysical movement, had raved over the strong, silent Hindu, and had even added a codicil to her will for the bestowal of a sizable gift on his cause, when with characteristic suddenness she had decided to be married at once.

She had known and loved Rodney Sayre more than a year, but had refused to give up her freedom until this season, when she quite took his breath away by proposing an immediate wedding.

Sayre, a worth-while chap, had a slight tinge of reserve and decorum left over from some old New England ancestor, and he was really the very one for Emily to marry, for he truly loved her and he had great tact and discretion in managing her.

Meekly, Emily had asked him to help her and teach her in the ways of calmness and dignity, for she knew, she said, that she was too volatile and effervescent to be a real companion to him otherwise.

And in moments of meekness or humility Emily was so bewitching that Sayre vowed he must learn of her, rather than the other way.

Emily was too restless to be beautiful, too excitable to be handsome.

She was pretty, of course—what girl isn’t nowadays?—but as her friends averred, her charm lay in her personality.

Poor overworked word that means so much, yet is always constrained to mean more.

In Emily’s case, it meant quick, vivid interest in persons and things, expressed by the most adorable little motions, unstudied, unselfconscious, but readily translated, quick, musical little exclamations, sudden, unexpected smiles, flashes of understanding eyes, queer little curves to her mouth—a thousand fascinating ways that meant Emily, and nobody else.

She adored Sayre, but she teased him unmercifully, for, as she told him, his own good.

Rodney, understanding, never resented it, but smiled at her in his big-hearted way.

But, innately, he rather scorned the meretricious and tawdry side of the gay crowd they went with, and hoped after he and Emily were married they would be also, what is, or used to be, known as “settled down.”

Not that he was a prig or a prude. He had no quarrel with the wildest escapades planned and carried out by his friends, but they sometimes failed to interest him. Yet he was so broad-minded and so really tolerant by nature that he never showed, or even felt, any annoyance at their pranks.

Burton Lamb, his chum, was the most irrepressible spirit of the crowd, so, as he and Sayre reacted on one another, it helped both of them.

Sayre was of the Viking type. Tall, fair and of magnificent physique, he bore himself with a swinging, easy grace that was one of the first things about him that attracted Emily.

“Most too big to stand in front of a fireplace,” she had said, looking at him critically, “but just grand to hand you down the steps and into the car.”

And at that speech Sayre had secretly determined to hand her into her car for the rest of his life.

And now the wedding was only about forty-eight hours away.

He was a bit disappointed at Emily’s insistence that she would keep her maiden surname in accordance with the views of her modern coterie, but he thought too, that she might be saying that only to tease him, and in any case she should have her own way.

So truly did he understand and respect the character of his fiancée that he was more than willing to let her do exactly as she chose in minor matters, or what seemed to her minor matters.

And so, when the gay group in the lounge, as Emily preferred to call the great living room, were talking about the personality of his bride, Sayre smiled a little to himself to think how perfectly he understood that darling person, and how easily he could persuade her to fall in more completely with his ideas, should he choose to do so.

The house party included only the out-of-town members of the wedding procession. There would be other bridesmaids and ushers from Hilldale Park, also a matron of honor, whose home, The Ravines, was near by.

Pete Gibby, a most adaptable and chummy sort, was asked because he was engaged to Betty Bailey, the maid of honor.

Gibby fitted in with the crowd, as he could fit in anywhere, by reason of his suavity and gay impudence.

Aunt Judy took to him at once, as she did to most of Emily’s friends, and it pleased Pete to pretend that Aunt Judy had ousted Betty completely from his affections.

“Yes, Mrs. Bell,” he said, sighing, “your personality is so marvelous, so perfect that I can’t help wishing—”

He broke off abruptly, as one overcome by deep feeling, and just then Emily came into the room.

“Talking about personality!” she cried; “you must indeed be hard up for a subject of conversation! I’m glad I came in—”

“Meaning you think we’ll talk about you?” asked Pete. “We do that when you’re not in the room.”

“Go right on,” Emily said, “I don’t mind a bit. I shan’t be listening. Oh, girls, the bridesmaids’ gifts have just come! Want yours now?”

“Straight off!” and Betty and Nell took the long slender white boxes Emily held out.

They contained cigarette-holders of an astonishing length and beauty. Of exquisite white enamel, with monogram in raised goldwork, they brought forth storms of approval and gratitude.

“One for you, too, Aunt Judy,” for Emily never forgot the old lady she had rejuvenated and given a new interest in life.

“And I’m going to have another thrill out of my own present,” Emily went on, as she perched herself on the arm of Rod’s chair, and leaned against his shoulder.

Slowly she opened the jewel case that held the bridegroom’s gift to her.

A long chain of diamonds, not large, but of faultless purity.

She let the necklace run through her fingers, like a small cascade of rippling light.

“Isn’t it beautiful!” she sighed, in an ecstasy of satisfaction at the lovely thing.

She flung it round her neck, and let it hang down over her dress, a sports frock of dark blue crêpe.

“I put on this dark thing, so it would show up better,” she explained, frankly looking about for admiration. “Isn’t it exquisite? Oh, Rod, it is just too darling!”

She clasped Sayre to her, and gave him a most satisfactory demonstration of love and gratitude.

Then she flew across the room to a mirror, and peacocked and pirouetted about, as she viewed her precious necklace from all angles and in all lights.

“How do you like it?” she smiled, leaning over the back of a chair, and letting the chain of stones run over the velvet cushions.

“Perfect!” declared Betty, and Sayre looked at the smiling eyes that held his.

Very dark, Emily’s eyes were, almost black, and their white lids, often falling over them, gave her at times the look of a siren.

Her face had a natural pallor, and though she carefully tinted it now and then from her compact, yet, her rouge did not hold like the other girls’ and much of the time Emily was positively pale.

“Red up, Emily, do,” cried Nell. “You look like your own ghost!”

“Lal Singh won’t think you’re pretty if you’re so white!” Pete declared. “Is he coming to rehearsal?”

“The Swami?” Emily tried to speak calmly, and did, too, but a quiver of her eyelids showed her slight embarrassment.

“Yes,” said Lamb, seeing a chance to tease; “I was going to tell his Reverence, the Garner, that you had left your fortune to Lally, but I was ’fraid you mightn’t want me to—”

“Hush your nonsense, Burt!” Sayre shot at him. “Do you s’pose I’m going to let you rag my wife—”

“Your wife!”

“Same as. Anyway, if you say a word she doesn’t want you to, I’ll—”

“There, there, Roddy, boy,” said Emily, standing behind him put a hand over his mouth.

Then she tweaked his thick, wavy hair, of a golden, almost yellow gloss, and announced:

“Gentlemen prefer to be blonds!”

Whereupon, Rodney jumped up and went for her.

Very dear she looked, caught in Sayre’s arms, her lovely head drooping on his shoulder, and her necklace dangling like a flashing thread of light.

Her dark bobbed hair was long enough to shake its soft curly sides and close-clipped at the back.

Leaning back against her big, strong lover, she stood, unconcernedly smiling at the others.

“And now,” she said, “we must get ready for the rehearsal. Spinks will be here about six, and I have to get into my—”

“Oh, Emily, you’re not going to wear your wedding gown at rehearsal!” and Aunt Judy looked really aghast.

“No, no, ducky; I’ve a sort of dummy frock, a make-believe wedding dress, with a long train and veil and all that. I’m going to rehearse in that.”

“Going to rehearse in the church?” asked Gibby.

“No, too much trouble. We’ll just go through the paces here. You see Spinks—”

“Who is Spinks?” asked Pete.

“Why he’s the Funeral Director. You needn’t laugh, because he is that, too. He takes full charge of the wedding parade, and you must all do exactly as he says. And obey him, or he’ll get awfully mad—”

“That reminds me, Emily,” Lamb put in, “Friend Garner is terribly alarmed for fear you won’t say ‘obey’ in the service—”

“Is he?” said Emily, indifferently, “then to tease him, I think I’ll say ‘Oh, boy!’ I heard of somebody who did—”

“Will the Penningtons be here?” asked Aunt Judy, to turn the subject.

“Oh, yes, Pauline is matron of honor. They’re coming over for tea, too. Be here any minute.”

“Is the Swami coming?” This from Lamb.

“I hope so,” and Emily faced him. “Oh, please do like my Swami-wammi! Don’t paste him all the time. Remember he communes with unseen worlds; he contemplates the Over-Soul—”

“Hush, Emily! What are you saying? Are you talking of Lal Singh?”

This speech, in irate and excited tones, came from the red, very red lips of a young woman just entering.

She was obviously angry, and as evidently the cause of her ire was the overhearing of Emily’s words.

“Oh, Polly, dear!” and Emily flew to greet the newcomer and kissed her with effusion.

Followed Jim Pennington, the husband of the angry Pauline, and in a moment, all the disturbance had blown over, tea was brought in, and everybody grew gay.

“Are you really the Mr. Pennington who writes those—those plays that I’m not allowed to go to?” Betty asked of the man who sat beside her.

“I hope so,” he returned, with a grave smile. “I mean I hope you’re not allowed to go to my plays.”

CHAPTER 2

A KISS FOR LUCK

“Why not?” and Betty’s round, chubby face registered fine indignation. “Girls nowadays can go to anything evil, see anything evil, hear anything evil—”

“You sound like the Japanese monkeys,” Pennington laughed at her. “And don’t say ‘nowadays’ to me! I’m not your uncle.”

Jim Pennington was a man of thirty, but to flapper Betty he seemed a generation removed. He was an erratic playwright, some of his work achieving marked success and some falling flat. One of his plays had been suppressed and others ought to have been, but they were not quite popular enough to make it worth while.

He was not distinguished-looking in any way, but his bored, languid air and his soft, drawling voice had an attraction for some women.

He made slight appeal to Betty, however, who liked her men louder and funnier.

“How’d you come to marry your wife?” she said, feeling she ought to startle a playwright.

“She made me,” returned Pennington, straightforwardly.

“Why, what a churlish speech!”

He stared at her, and comprehended.

“Oh,” he laughed, “I didn’t mean it that way! I mean she was the making of me—of my career. Her sympathy and help—”

“I see—your dearest friend and severest critic—or whatever it is. She’s very beautiful, too.”

“Yes; if she weren’t quite so pretty, she’d be the most beautiful woman in the world.”

“Does that mean anything?” asked Betty idly. She was bored with the man, and didn’t want to waste any sparkle on him.

“Not to you, I daresay. Are you to be maid of honor?”

“Yes, and Mrs. Pennington is matron of honor, I know. We’ll do well together.”

“Watch your step, then. Polly is a marvel when she’s in regalia.”

“So’m I,” returned Betty; “what’s she going to wear?”

“Lord, I don’t know. Let me see—she should wear—oh, well, nothing short of a complete Carmen costume brings out her best points.”

“Yes, I can see that. She’s a perfect Carmen. That wonderful black hair, those eyes—even the very way her cigarette droops from her lips. Do you care for any other woman, Mr. Pennington?”

“Woman? No. Women? Yes. I adore many of them. May I adore you?”

“’Fraid I haven’t time. There are so many enticing strangers here. Look at that man who just came in! Is he the one they’re all crazy about?”

“Yes, he’s the Swami. His name is Lal Singh. I think he’s a faker.”

“Fakir with an i or an e?”

“All the same. Want to meet him?”

Betty did and the two went across to where the Swami and Emily were talking together, a little apart from the rest.

“Do we intrude?” said Pennington lightly. “Miss Bailey wants to meet a real live celebrity.”

Lal Singh bowed, gravely accepting the compliment.

Whereupon Betty monopolized him, and Emily turned to Pennington.

“Where’s Polly?” he asked.

“In the present room. Oh, Penn, look at my necklace! Isn’t it perfect?”

“Let me see it,” and Pauline Pennington came toward them. “Yes, Emily, it’s awfully good. Might have been a bit heavier—”

“Not at all. I wouldn’t have it of larger stones. Just because Penn gave you a Kohinoor—”

Polly held up her chin, as if to show off better the diamond pendant that had been her wedding gift six years ago.

“Funny for you to have the Rehearser, Emily. What’s the idea?”

“Oh, everybody does now. Of course, six years ago, such a thing was unheard of, but it’s a great discovery, really.”

“But Spinks is the undertaker.”

“What of it? Can’t he undertake a wedding as well as a funeral?”

“Oh, you give me the creeps—”

“Don’t come to rehearsal if you feel nervous about it, Polly dear.”

Emily was not of a catty disposition, but Polly Pennington, though one of her dearest friends, often rubbed her the wrong way.

Moreover they were rivals for social queendom.

Emily, as a belle and heiress was easily first with the younger men, but Polly, who was really a married flirt, had a long list of admirers.

The two girls were opposites as to character, Emily being daring, unafraid and impulsive.

Pauline, nearly seven years older, had learned to be diplomatic, discreet and careful. She had the mentality of a Machiavelli and the suave countenance of a Mother Superior.

Not that she looked nun-like. Her suavity was a mask and she meant it to be known as a mask. Beneath it were fires of many sorts, to be kindled or extinguished at her pleasure.

Emily’s personality was frank, free, and open. Pauline’s was deep, mysterious, hidden.

Yet the two were friends, after a fashion, and Emily never fought Pauline with her own weapons of sarcasm and pettish faultfinding, unless goaded to it.

And during the preparations for the wedding Pauline had been especially irritating. Both jealous and envious by nature, she resented Emily’s triumphs and sought to belittle the elaborate plans.

“Oh, yes, I’ll come,” she answered Emily’s suggestion. “I want to see what the undertaker person does. I never should have had such a thing at my wedding.”

“Of course not—seven years ago.”

“Six.”

“Well, six, then. You see, modes were very different then. How would I look having the sort of wedding you had?”

“What do you know about it? You weren’t there!”

“No, I was in the nursery. But, now, the Rehearser is a regulation thing; one has to have him. You’ll see.”

“And that Spinks is a general-utility man. Why, he manages bridge games and costume parties.”

“Of course he does. He attends to everything except christenings—”

Emily stopped suddenly, and quickly changed the subject. There had been one great tragedy in Pauline’s life, the loss of her baby.

She worshipped the child, really idolized it, and when the little thing died of croup the night before the christening day, Polly Pennington almost went mad.

Highly strung and nervous of temperament, she was a long time regaining her poise and her health.

Her friends even now were careful not to mention children or christenings in her presence, and Emily’s slip was a real catastrophe.

She turned quickly toward the pair at her side, Betty and the Swami.

The Hindu would, she knew, distract Pauline’s attention at once.

“Come with me, Betty,” she said, peremptorily. “There’s some one I want you to meet.”

Betty was enjoying herself and didn’t want to leave, but the look on Emily’s face compelled her, and she obeyed.

“Wassamatter?” she said, curiously. “You and Polly had a spat?”

“No. Keep still, do.”

She shepherded Betty across the room toward a man who had just come in.

A man much older than the rest, a man who gave the effect of an elderly beau, which, indeed, is just what he was.

Abel Collins, sixty or thereabouts, was the friend of all the world.

He had been a friend of Emily’s parents and had known and loved the girl all her life.

His bright, blue eyes gleamed from beneath shaggy gray eyebrows, and his gray hair, a bit long, curled at the ends.

He was good-looking in the sense that he looked good and his attire was immaculate, if not quite of the latest styles.

He put an arm round Emily without speaking to her and held out a hand to Betty as Emily introduced them.

“My godfather,” Emily said, “and my guide, philosopher and friend. My overseer and general superintendent. My mentor and tormentor—”

“There, there,” Abel Collins interrupted, “I’m sure Miss Bailey knows enough about me now to last the rest of her life. Let’s talk of something else.”

“Talk about me,” said Betty promptly. “I’m maid of honor, and I’m next to the bride in importance now, and as soon as she goes off with Rod, I’ll be top of the heap! I guess you’ll be glad then that you know me, Mr. Collins!”

“Oh, I hope so,” he returned. “My dear young lady, I truly hope so! And if you’ll only behave yourself—”

“Now, now,” said Betty, taking to him at once, “don’t set me too hard a task—”

Seeing the two fairly launched on a gay conversation, Emily slipped away from Abel Collins’ clasp and went to Sayre’s side.

She slipped naturally into Rodney’s circling arm and joined in a spirited discussion he was having with Burton Lamb.

“You’re crazy, Burt,” Sayre was saying; “what do I care what Emily does?”

“Why, why!” Emily said, smiling up at him as she felt his arm tighten round her. “What’s the wild Lambkin saying to make my sweetie talk like that?”

Her perfect faith and trust left no room in her heart to imagine that Sayre’s words cast any aspersion upon herself, as indeed they did not.

“He’s a goof,” Rodney informed her. “And he’s also an interfering old cuss and a general rotter. Want to know any more?”

“I do,” said Emily, “I want to know it all. First, the subject of the debate.”

“No debate about it,” Lamb said, with some heat. “I merely told this lunatic that you’re planning to marry that you had been bamboozled into giving a lot of money to the present pet of Hilldale, the dear little Swammikins—”

“Oh, that!” and Emily laughed. “Well, go on, my Lamb, go on; I’m a member of the What-Of-It? Club.”

“Oh, nothing much,” said Lamb, airily, “only I thought any good citizen who dared ought to remonstrate with you.”

“And I interrupted friend Sayre here as he was saying he doesn’t care what Emily does with her money, didn’t I?”

“Exactly that,” agreed Rodney, glad that Emily had sensed his meaning.

“Exactly that,” agreed Lamb. “So, as best man, I think it my duty to do a little in the remonstrating line myself.”

“Why?” and Emily was suddenly serious.

“Because, Emily dear, I’m sure that man is a fraud. He’s not a real Hindu, to begin with, and if he is, he isn’t the holy man he pretends to be.”

“Burton, darling, you’re a brick. It’s nice of you to put me on my guard. And to tell you the truth, I more than half believe you’re right. But you see I didn’t pay him any money; I only added a codicil to my will that he shall receive a bequest for his charitable work when I no longer have any use for such things. I don’t intend to die for a long time yet, but if I should, I won’t begrudge the legacy. Whether he’s the real thing or not, he has entertained us all and has wormed himself into the good graces of the Hilldale people.”

“But, Emily, if you knew anything about theosophy, anything about Hinduism—”

“Never mind the isms; he can spout the lore of Farther India, or whatever it is, farther than any Orientalist I ever knew before. And his talk when he’s alone with you, would charm the birds off the trees!”

Sayre bent down and kissed the top of her head, to show that he was not jealously roused by this revelation.

“And another thing,” Emily went on, “since you feel so deeply about the matter, I’ll tell you there’s nothing in it.”

“About fifty thousand dollars, I’ve been told,” Lamb put in.

“Yes, on paper.”

“But aren’t wills usually on paper?”

“Yes, O wise one. But, hearken. Said will, on said paper, becomes null and void when Miss Emily Duane, Spinster, becomes Mrs. Rodney Sayre, Matron.”

“Of course it does!” and Lamb’s face broke into smiles. “I knew that, but I forgot it. Oh, Emily, you’re all right!”

“Then,” Sayre said bewilderedly, “when you go off with me on our wedding trip, you leave no will behind you?”

“That’s right, my best beloved,” Emily returned. “Should battle, murder and sudden death o’ertake me, you are my sole heir—”

“Hush, Emily, you shan’t say things like that!”

“Well, my Heavens! Rod, you’re my only heir anyway, so what need for a will?”

“There’s Aunt Judy—”

“Yes, dear, but I trust her to you. And, anyway, I’m to have a little talk with Mr. Craven about all this tonight or tomorrow. And there’s his massive dome now!”

Burton Lamb turned to look at the mentioned lawyer, but his glance paused halfway, for he caught sight of Lal Singh staring at Emily.

His face was distorted with passion, and it was impossible not to realize that he had heard Emily’s remarks about her bequest to the Hindu and was greatly upset in consequence.

Lamb chuckled, for he had no faith in the Oriental’s sincerity and hoped he would never receive a cent of Emily’s money.

To be sure it was a legacy, but he was apprehensive lest the wily mystic might persuade Emily to make a cash payment in advance.

After her pronouncement, however, he felt at ease about the matter, and in a moment, Everett Craven, Emily’s lawyer, joined their group.

Lamb then faded away, for he felt the business confab was only for the principals, and even a best man was not needed there.

Everett Craven had long been a suitor of Emily’s. Though several years older, he was a man of persistency and determination, and her repeated rejections seemed only to intensify his resolves to win her.

Of course, since her engagement to Sayre had been announced, Craven had given up hope, and though still attending to her legal affairs, he was a changed man.

A good lawyer, though of no brilliance, a good citizen, in a non-committal way, Craven had few friends and no enemies. He was uninteresting and rather self-centred.

As a matter of fact, Emily had thought little about him. She rejected his proposals as fast as he made them, and then, as he showed no special resentment, she continued to retain his legal services.

Craven continued because she was his best-paying client and he had none too many.

So now, taking the opportunity, Emily spoke to him, in Sayre’s presence, about her will, and about the advisability of making a new one to be signed after she was married, and before starting on her wedding trip.

“But there isn’t time now to discuss this thing at length,” she said, glancing at her watch. “Will you come tomorrow morning, at ten, and we can go into it? You see, we’re having the rehearsal soon now, and I have to get rid of these people.”

She danced away and Rodney’s watching eyes saw her go into the telephone booth. This was just outside one of the doors into the lounge, and Emily found her maid, Pearl, hovering in the hall.

Pearl was a negro, as black as jet, and devoted, soul and body, to her Miss Em’ly.

Not much older than her mistress, Pearl did everything for her, and was so capable as a personal maid, a needlewoman, and to a degree, a social secretary, that Emily was tempted to take the maid with her on her wedding trip. But the desire to be alone with Rodney for their honeymoon was too strong, and Emily had decided to leave Pearl at home, and send for her if she needed her too greatly.

She smiled at the grinning negress as she entered the booth.

There was great understanding between the two, and Black Pearl, as she was of course called, stood sentinel at the door of the booth.

As Emily became excited and her voice rose in exclamation, Pearl, too, rolled her eyes in delight, and clapped her hands softly.

For she had overheard Emily’s part of this conversation:

“Is this the hospital?”

“Yes, madam.”

“May I speak to Nurse Graham?”

“I’ll see. Wait a moment.”

“This you, Nurse Graham?”

“Yes, Miss Duane.”

“Has Mrs. Laurence’s baby arrived?”

“Yes, Miss Duane.”

“Oh, lovely! What is it?”

“A little girl.”

“Fine! How is Mrs. Laurence?”

“Doing beautifully. I must go now—”

“Wait a minute, Nurse. Listen. If I come over, right away, now, can I see her?”

“Mrs. Laurence!”

“Oh, no, no! The baby, the little girl—”

“Oh yes, you can see the baby. I’ll show her to you myself.”

“All right, be there in ten minutes. Good-by.”

Emily hung up the receiver, left the booth, flung her arms round Black Pearl and danced her down the hall, then ran back to the lounge.

People were leaving, and though Emily gave farewells to a few, she whispered to Aunt Judy to attend to that for her, and told Betty Bailey to help Mrs. Bell.

Then she turned toward Sayre, who was where she had left him, and as she passed the Penningtons, she saw they were just going.

“By-by, Polly,” she said, “come over for rehearsal soon after six—unless you’re afraid of the undertaker!”