Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

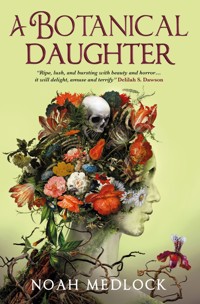

Mexican Gothic meets The Lie Tree by way of Oscar Wilde and Mary Shelley in this delightfully witty horror debut. A captivating tale of two Victorian gentlemen hiding their relationship away in a botanical garden who embark on a Frankenstein-style experiment with unexpected consequences. It is an unusual thing, to live in a botanical garden. But Simon and Gregor are an unusual pair of gentlemen. Hidden away in their glass sanctuary from the disapproving tattle of Victorian London, they are free to follow their own interests without interference. For Simon, this means long hours in the dark basement workshop, working his taxidermical art. Gregor's business is exotic plants – lucrative, but harmless enough. Until his latest acquisition, a strange fungus which shows signs of intellect beyond any plant he's seen, inspires him to attempt a masterwork: true intelligent life from plant matter. Driven by the glory he'll earn from the Royal Horticultural Society for such an achievement, Gregor ignores the flaws in his plan: that intelligence cannot be controlled; that plants cannot be reasoned with; and that the only way his plant-beast will flourish is if he uses a recently deceased corpse for the substrate. The experiment – or Chloe, as she is named – outstrips even Gregor's expectations, entangling their strange household. But as Gregor's experiment flourishes, he wilts under the cost of keeping it hidden from jealous eyes. The mycelium grows apace in this sultry greenhouse. But who is cultivating whom? Told with wit and warmth, this is an extraordinary tale of family, fungus and more than a dash of bloody revenge from an exciting new voice in queer horror.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 442

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Part I Germination

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Part II Cultivation

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Part III Propagation

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise for A Botanical Daughter:

“This book is the most fun a reader can have while still gritting their teeth in fear! Enchantingly eerie and upsettingly lovely, A Botanical Daughter is an intoxicating hybrid of blood, botany, and old-timey charm.”

Andrew Joseph White, New York Times bestselling author of Hell Followed with Us

“Ripe, lush, and bursting with beauty and horror, A Botanical Daughter will delight, amuse and terrify, all while breaking your heart. Perfect for readers who can imagine Frankenstein as created by the characters of Good Omens in the Garden of Eden.”

Delilah S. Dawson, New York Times bestselling author of Bloom

“Macabre and magnificent. Horrifying and hilarious. Oddly and unquestionably heart-warming. A delightfully gruesome and rather brilliant debut from Noah Medlock. A viciously violent Victorian romp that would have Mary Shelley saying ‘Damn!’”

Angela (A.G.) Slatter, award-winning author of The Path of Thorns

“Medlock invites readers into a rich and sumptuous world in a dark and charming novel full of macabre delights. The perfect blend of classic science fiction and horror, wrapped around a core of found family, love, and heartbreak – this story hits all the right notes.”

A.C. Wise, award-winning author of Wendy, Darling

“Deliciously arch and bursting with eccentricity, A Botanical Daughter starts its uncanny life as a cosy-yet-macabre look at found family. Soon, however, it grows, steadily and with skill, into a vegetal monstrosity, forcing us to look – not without a shiver – at the horrifying ‘other’ and the boundaries of personhood. An extraordinary debut.”

Ally Wilkes, author of All the White Spaces

“This flourishing horticultural horror could only be the monstrous byproduct of a mad phytologist, Mary Shelley grafted onto Jeff VanderMeer, a gothic greenhouse of sporror that reaches down deep into the substrata of the reader’s subconscious and eternally takes root. I absolutely loved it.”

Clay McLeod Chapman, author of What Kind of Mother and Ghost Eaters

“A dreamlike green Frankenstein. Medlock’s debut is full of uncertainty and charm, where wonder and suspense grow entangled with each other in a book that grips you tight. A captivating weird gothic.”

Hailey Piper, Bram Stoker Award®-winning author of Queen of Teeth

“Medlock’s fertile imagination has given rise to a neo-gothic novel that twines ideas of life, death, and humanity together in an inexorable, fecund embrace. Beautifully macabre and monstrously, joyously queer, A Botanical Daughter wrapped its tendrils around my heart and slowly squeezed until I was quite short of breath. Expect it to grow on – and in – you.”

Trip Galey, author of A Market of Dreams and Destiny

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

A Botanical Daughter

Print edition ISBN: 9781803365909

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803365923

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: March 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2024 Noah Medlock. All Rights Reserved.

Noah Medlock asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For James

part i

germination

One

It is an unusual thing, to live in a botanical garden. But then again, Simon and Gregor were an unusual pair of gentlemen.

You might imagine that the vast greenhouse at Grimfern would be too stuffy for human habitation. You would be more or less right, though Gregor Sandys—that notorious botanist—had become accustomed to the garden’s balmy climate. Grimfern’s many brilliant glass surfaces were always covered in a sheen of condensation, so he developed a habit of carrying a handkerchief in every pocket for the sole purpose of wiping his spectacles. His sumptuous fruit trees and exquisite orchids required such moisture and heat that by the end of a hard day’s gardening he could practically wring out his cummerbund. Gregor would swelter at any temperature though, cooking slowly like a steamed ham, for his precious collection of botanical curiosities.

In a house made of glass, the dazzling sun was a constant worry. An embellished wrought-iron frame held up countless artisanal panes, and if a denizen of the garden were caught off-guard by a passing sunbeam—or even by a particularly flamboyant candle flicker—he would be quite incapacitated by the light’s furious beauty. Simon Rievaulx, the other resident at Grimfern, had set up his taxidermy workstation in the cool, dark basement of the glasshouse precisely to avoid this problem. Down there, beneath even the boiler, he could make sure that his compositions did not spontaneously de-compose by keeping his cadaverous creations, and himself, pleasantly chilled.

The immense roof of the central dome was a masterpiece of levity through structural integrity—a hallmark of Victorian engineering. The Grimfern Botanical Garden was a prismatic Hagia Sophia—a fountain of jewelled rafters. Even the great Crystal Palace in London would be jealous of its bespoke glasswork. Gregor had taken care to fill his glass mosque not only with greenery, but also with music; he had his mother’s piano placed carefully under the great dome to achieve maximum acoustic effect. There he would sit of an evening and swoon to the excesses of French and Bohemian composers. Of course, the great glass roof made a great damn clatter when the storms hit, so even under its shelter Gregor’s rhapsodies could be rained off. In addition, the heat and damp played havoc with the beast’s temperament. Even the simplest étude became savage with its barbarous tuning.

The final complaint to be discussed here about living in a rococo conservatory is the sheer lack of privacy. Simon and Gregor, being confirmed bachelors, had no qualms about keeping each other’s company. Well, they shared one qualm—that they should guard their own workspaces as sacred to themselves. Simon never visited the west wing where Gregor conducted his research, and Gregor never descended the stone steps to Simon’s refrigerated taxidermy practice. They slept, washed, and cooked in the east wing of the gardens, which was split up with luscious ferns and vines into smaller rooms. A playful device allowed for a bath or shower in amongst tropical foliage, with the jungle flora appreciating this steamy atmosphere.

An odd thing about this notionally see-through house was that barely anyone, except for the two gentlemen inhabitants, ever actually saw inside. It was set upon a commanding hill with a long, sweeping lane, stone steps, and terraces. It was ringed by a thick hedge and guarded by sentinel poplar trees. The wider grounds were kept by a squadron of villagers, handpicked for their discretion, or for their un-inquisitiveness. They trimmed the lawns, spruced the bushes, mucked out the horses, and so on, enjoying generous pay and limited oversight from Mr Sandys. But they were never to set foot, or even peer, within the topiary fortress where the masters lived.

The only villagers who even came close to the greenhouse were the post lad and the girl who dealt with the laundry. They would meet Gregor at the top of all those steps, where the privet reared up into an arch over an iron gate, to swap fresh mail for dirty clothes, and vice versa.

The story starts here at one such exchange, in part because the boy—Will—carried with him a long-awaited delivery: a crate marked with angry customs notices in both Dutch and Malay. But we also start here because the girl—Jenny—was entirely absent.

* * *

“Package for you, sir. Straight from Araby, by the looks of it!”

Gregor eyed the crate with ill-concealed glee.

“It is a specimen from Indonesia, in fact.” He dropped his canvas sack of laundry and hefted the rough-hewn box from Will. “And it took more than a few well-chosen words in the ears of powerful people to get it back here.”

The young man just smiled and shrugged, making the most of his time near the greenhouse to nosy around the patio. Gregor tolerated this indiscretion, as all he could spy on would be the meticulously spherical rose bushes. The view inside the greenhouse was blocked by emerald, sun-hungry leaves, thick and waxy against the steamed glass.

“I guess Johnny Foreigner doesn’t like you nicking his plants.”

“I didn’t steal this, I discovered it. And it’s not a plant. It is a fungus.”

“Finding or robbing, flowers or fungus. Can’t tell the difference, myself!” Will said with his cock-eyed smile. The corners of Gregor’s eyes creased behind his spectacles, but he held his tongue. Now there was only the matter of the laundry bag, slumped on the floor between them. Both men stood there, just blinking at it.

“The girl—she isn’t here?”

“No, sir,” said Will, “Jennifer’s not turned up today.”

“Whyever not?”

The lad shifted his weight, his countenance darkening. “It’s a sorry business, Mr Sandys. It seems—”

“Question withdrawn. She can pick up the laundry next time. Good man. Off you pop.”

Gregor turned sharply and rushed his acquisition to the laboratory, dragging the laundry behind him. He dumped the linen sack in the entryway, with shirts and smalls spilling out onto the stonework. The post he cast carelessly near enough to a sideboard near the door. He had better things to do—there was botany afoot.

* * *

Simon emerged from his underground workshop, blinking in the full light of morning. His jaw was pale and sharp, and scrupulously shaven. He stopped briefly at the pile of clothes on the stonework floor, looked this way and that, then stepped clean over it with his gangly legs.

“Was there any post for me, Gregor?” he called into the west wing.

“Probably,” might have been the muttered response.

The sideboard was empty. The sideboard which was placed there for the express purpose of receiving the mail. Simon tapped it. That was where the post was supposed to be. There was laundry on the floor and no post on the sideboard. The whole world was out of alignment. Such things irked Simon in a way that he had learned never to show.

“Where is it?” he asked back, in a practised, even tone.

“By the door!” came the distant, disinterested response.

By the door. But not on the sideboard. Simon turned a full circle before his doleful eyes fell upon a pile of envelopes, sticking out of a large terracotta pot. Barely a foot away from their proper place, on the sideboard, the sideboard put there to receive the post. He retrieved them stiffly (he wore his pinstripe trousers slightly on the too-tight side) and brushed off the potting soil.

One letter, addressed to him personally, displayed such lavish penmanship that he opened it hurriedly with a grin.

* * *

[Letter from Rosalinda Smeralda-Bland, dated Saturday 8th June 1889]

Dearest Simon,A curse upon the botanist! Has he no love for me, the greatest (and presumed last) of his admirers (other than your own, dashing self)? The letters I have written to him, so carefully crafted, so stuffed with adulation, I fear have languished unopened upon his potting shed bench. So much love—so much stationery—wasted!

I implore you, darling Simon, when you next see the elusive gardener, to strangle him with his own watering hose. And after that, give him the news that I intend to visit Grimfern on Whitsun to see what botanical wonders he has in stock. I have been badgering him for weeks about it, and in the absence of a response, I shall take no ‘no’ as an invitation.

See you tomorrow, Simon.

Love to you both,

Rosalinda S-B

P.S. Fair warning—I shall have to bring Mr Bland, I’m afraid…

“Rosalinda’s coming, Gregor, to buy some plants. On Whitsun—that’s today!”

Gregor was finally interested enough to emerge from his laboratory, dressed in an apron and carrying a crowbar which he had used to open his Indonesian crate.

“Today? She can’t come today. She didn’t tell me!”

“From the tone of her letter, I think she rather did, in fact.”

Gregor took the letter and skimmed it, squinting in the absence of his spectacles which were perched, forgotten, above his auburn hairline. “Shame about Mr Bland. It will be nice to see Rosie, though.”

“But, Gregor!” Simon’s large eyes were even wider than usual. “The greenhouse is in disarray! Plates and glasses here and there, post in the plant pots, clothes all over the atrium—”

“Oh yes, the girl didn’t come to fetch the laundry.”

The clothes sack could, of course, have been moved anywhere other than the middle of the floor, directly by the greenhouse entrance. It would be a chore of a matter of mere moments to place it elsewhere, but Gregor had not the drive and Simon had not the grace to do it now, themselves. As far as these stubborn fellows were concerned, the clothes would have to remain there for the rest of eternity.

“The girl—Jennifer Finch, isn’t it?” asked Simon.

“Possibly. I—”

Just then, there came a thud from Gregor’s laboratory in the west wing. There was nobody except for the two of them in the greenhouse. Gregor frowned, growled something about the wind, and disappeared behind screening vines to find out what must have fallen.

Simon chewed his lip and put on his black silk gloves. He happened to be planning a visit to Jennifer’s father, who sold him animals of dubious provenance for use in his taxidermy works. He would go there today and ask after his wayward daughter. There was little-to-no hope that Gregor would do anything about the laundry issue, and perhaps by speaking to the Finch girl, Simon could resolve it without actually having to do any housework himself, either.

* * *

Gregor bounded back into his laboratory, the straps of his apron flapping behind him. It was a bracing, bright day, and there were cloud-shadows scudding along the brick floor.

Gregor’s workshop was messy, but it was a human’s mess rather than Nature’s. In the great central atrium, he had meticulously planned and maintained Nature’s chaos to resemble itself. Tropical plants were laid out in a riot of colour and shape—it was Gregor’s scrupulous organisation and upkeep which kept it looking spontaneous. In his laboratory, however, careful filing systems and square trays of seedlings, which should have spoken of humankind’s impulse towards systematisation, lay scattered and chaotic in Gregor’s tempest of genius.

Gregor stalked around the various workstations, trying to spot a stray animal or a broken pane—the potential source of a bluster. But there was no sign of a further disturbance, nor even of anything having fallen to make the noise.

Until he looked back at his newly arrived crate.

No sooner had he prised the lid open, Simon had called him back to the atrium. Gregor had reluctantly left the crate slightly open, its lid just off-kilter. Now though, it was squarely shut.

“Who…” Gregor began, before holding his tongue. There was no one in the garden besides himself and Simon.

He pulled at the lid, but it gave more resistance than he expected. He finally wrenched it open and the contents released a puff of mildew, before shaggy tendrils of grey broke between the contents and the lid.

This was the precious specimen Gregor had imported, at no insignificant cost, from the Isle of Sumatra to his greenhouse in sleepy Buckinghamshire. Out there in Indonesia he had discovered this mycelium with miraculous properties. But had it… closed its own crate?

He looked at the torn threads between the lid and crate. Thin wisps looked almost white and cottony. There was a root system spread throughout the box—the aerial roots of an orchid, which sprouted into a small cluster of leaves, and bore a single, bell-like flower. The poor plant was nearly engulfed by the mycelium. Thicker globs of the fungus, a bulbous mass, were huddling up in a dark corner. Cowering, almost.

“You don’t like the sun much, do you? And you have a little friend—what a pretty orchid. Wait—areyou…”

Despite the unfavourable conditions, the orchid seemed to be flourishing. Its flower was firm and vivid, violet and green with spots of rich burgundy. The shape was florid and round, yet exquisitely pointed—as if it had been rendered in the Art Nouveau style. These kinds of orchid—Paphiopedilum—grew on the jungle floor, far away from any direct sunlight. This one was an absolute beauty.

“Are you protecting your pretty flower from the light?”

He placed the lid down in a diamond shape upon the square crate, then crossed the room to his experimental jotter. He scribbled some initial, unstructured thoughts and eyed the box carefully over the rims of his steamy spectacles.

After a few minutes, Gregor heard a scuffling coming from the box. The lid trembled, and so did Gregor’s writing hand. Then, with a scrape and a thud, the lid slotted squarely back into position. Gregor scratched a blasphemy into his notebook, which will be left to the reader’s imagination.

Gregor reapproached the crate with great caution. He wiped his spectacles and scratched his beard. Instead of opening the lid once more, he carefully removed a plank from the side of the box and peered inside.

In that murky cave, the mycelium had reached up like so many stalagmites to coax the lid back into place. That way, the orchid would only be exposed to the filtered light creeping in between the crate’s thin wooden planks.

“You’re a very motivated mycelium, aren’t you,” Gregor muttered, “and not a bad little gardener, to boot.”

After gazing for a while at the miraculous contents of his delivery, he felt a tiny fleck brush against his cheek. He jumped and shuddered, until his eyes refocused on a slim finger of grey—a wormlike appendage scoping the surroundings. Before his very eyes, the thing was burgeoning out towards the intrusion of sunlight.

“Oh no you don’t, you little bugger.”

Gregor fixed the plank back onto the box and scribbled a couple of pages of notes. Then with his whole arm he slid his other, lesser, experiments to one end of the central workbench. The Sumatran mycelium would take pride of place, both in his workspace, and in his fevered mind.

Two

Simon saddled the grey mare and set off down the sweeping lane, leaving Gregor to his inscrutable research. Simon disliked riding horses but growing up in a forthright religious household had perfectly accustomed him to doing things he disliked, and not doing things he did like. He did not care for animals, for example—his profession was a mere accident of talent. It wasn’t his fault he was good at stuffing God’s creatures and posing them to lampoon the social mores of the day. He had tried sculpting in other materials—in clay, marble, wood, and bronze—but corpses were the only medium that really sang under his fingers.

The Finches lived in a ramshackle water mill on the edge of the village. The ride there was smooth enough through the sultry summertime country lanes, but his several layers of miserable black tweed quickly had Simon hot and bothered. Florence the mare was a stubborn horse, who would never let her fatigue show to her rider. Simon admired that. Together they suffered in silent dignity all the way to the little water mill.

He tied Florence to a post and wrestled with the gate to no avail. The catch did not want to budge, and Simon’s over-developed sense of decorum did not allow him to rattle it with enough force to free it. He glared over at Florence, but she was not of a mind to help. At long last John Finch stepped out of the mill cottage, wiping his hands with a rag. He was a gruff widower of some muscle and little joy. These days he earned more through poaching than he did through milling, and Simon would often make the journey down from Grimfern to avail him of his catch.

“Oh ’eck, here’s death come to take me at last,” Finch mumbled, chucking the red rag into a bucket.

Simon looked over at him with his huge, dark eyes. The former miller’s mouth was a perfect parabola, as if a child had drawn him ‘sad’. In reality you could never tell what he was thinking, as he would always pull his mouth into that shape whether he was impressed or indifferent.

“Gate’s stuck,” was all the old man had to say.

Simon’s voice was muffled as if coming from far away—he barely moved his mouth and kept his jaw firmly clenched. Ventriloquism is a side effect of social awkwardness. “Good afternoon, Mr Finch. I was hoping to enquire as to—”

“Yeah, yeah, I’ve got your stuff,” growled Finch, batting away the words like so many midges. “Three hares and a pair of pheasants. Usual price.”

Simon was really here to ask after his daughter but could not resist the lure of raw material—a blank canvas.

“And were they properly—”

“Killed in the right way, as you like them, lad.”

Simon needed there to be no ugly scars or damage to the bodies of his subjects, and as such had exacting requirements as to the method of killing. John Finch didn’t ask questions—as far as he was concerned, the money man was always right. He fetched the merchandise from their hanging spot in the doorframe. Simon paid him and loaded the carcasses into Florence’s saddlebag.

“Ah, but the principal reason for my visit this morning… is your daughter. Or rather, her absence. Is she… How is your daughter, Mr Finch?”

Finch removed his flat cap and scrunched it up idly. Simon had never before seen the top of the man’s head. The grizzled grey of his temples stopped suddenly where the brim of his hat started, and the roof of his head was bald as a tonsured monk.

“There’s been some upset. Jenny’s little friend. The Haggerston girl. Close as sisters, those two were. Gone. The way of all things, God knows.”

“I’m so very sorry to hear that. How old was she?” asked Simon.

“Not old enough. Barely nineteen, I should think. But then again, nobody is ever old enough. My Mary, Jennifer’s mother… Well, sod it. There’s nowt to be said.”

Simon could not allow the feeling of grief to seep into his emotional fortifications, or he would be overwhelmed then and there. He nodded in understanding and copied John Finch’s stiff-lipped frown.

“In which case, Jennifer’s absence from work is understandable. Please send her my—”

Casting the briefest of glances at the miller, Simon started. He was looking right at Simon, which made them both uncomfortable. Normally their business was conducted facing at right angles from one another, as befitted the awkward transaction of two dour men trading dead bodies. But now John Finch was looking straight at him, and Simon was obliged to attempt eye contact.

“Mr Rievaulx—Simon,” the older man began, with a sigh in his voice, “you gents have got a big house up there, an’t you. Lots of rooms and so on…” His sentence carried on into inaudible mumbling that couldn’t escape his unruly beard.

“Not so many rooms, just one cavernous glass vault. What is it that you are implying, Mr Finch?”

“It’s just—Jennifer, get out here, will you?” he bellowed over his shoulder, before returning to face Simon, piteously wringing out his workman’s cap. Simon had never seen him like this before.

Soon Jennifer, Finch’s daughter, appeared in the yard, her hair as wild as gorse. Her smock had many pockets, stretched from frequent use. Her boots seemed too big and her sleeves were too short, revealing bramble scratches all up her arms. Her freckled cheeks were red from a glut of angry tears.

“My Jenny’s been looking for more work than she has now with your laundry. Idle hands, and all that. Keep her mind off… everything. Only, there’s not much call for her in the village, and she’s not got the temperament for the well-to-dos in town.”

The young woman opened her mouth as though ready to summon a hurricane of indignation, but then couldn’t seem to manage it. Grief can be a kind of exhaustion, after all.

“She’s a blustery spirit, Simon, I won’t lie to you. Got an air of her mother about her. But she could fit well with your… unconventional arrangement, and she’d work damned hard.”

Jennifer raised her chest and gave Simon an attempt at a cock-eyed smile.

“What you’re saying is, you want us to take her on, as a housekeeper?”

“That’s the long and short of it. You’d be doing us a big favour, sir.”

If you were to observe Simon closely at this point, you could just about make out a throbbing of his perfectly shaven jaw, indicating its repeated clenching and unclenching. Nothing else about the poised gentleman would betray his distress.

“You must understand, our travails require a great deal of secrecy and discretion. It is a working greenhouse. We have never employed a housekeeper before. We do the housework ourselves. Well, I do the housework. Most of it. Well…”

Simon drifted into a reverie of clothes piled high around wicker baskets, plates unwashed, beds unmade, floors riddled with moss and weeds…

John Finch moved closer to Simon so he could speak in such a way that his daughter wouldn’t overhear. She was clearly unimpressed but looked away pointedly.

“Look, Simon,” he said, a tremble in his voice, “I’m out on a limb ’ere. There’s nothing left, no hope in the village for her, no life for her here with me. There’s no money for any of it. I’m not expecting you to pay her a decent wage, I just need someone to look after her. I don’t think I can any more.”

Simon felt for the old man in his sorrow but had no idea how to comfort him. He simply patted him, rather stiffly, on the shoulder. John Finch smelled of fresh earth and dried blood.

There was not a real chance of Simon saying ‘no’ to all of this. Still, he built himself a framework of rationalisation that made it seem like his own idea. They did need help around the greenhouse, after all. Even if Gregor did not care about the order and cleanliness of anything that wasn’t growing and green, Simon did. The living quarters’ disorder truly irked him, but spending all day keeping it in check also left him with layers upon layers of resentment. So, Jennifer could tidy up and bring balance to the ménage in one fell swoop.

“What do you know about plants, Miss Finch?”

“Only what to eat and what not to eat.”

“That will serve you in good stead. And what do you know of taxidermy?”

“Of what?”

“Excellent. Mr Finch, I will employ your daughter. We must return to the Gardens at once to make plans. Do you ride, Jennifer?”

Jennifer gave a pffft of derision, hitched up her skirts and swung herself up onto the grey mare, straddling it in a most undignified fashion. Simon’s eyes were wide as teacups. John Finch wiped his nose on the back of his hand and beamed broadly. He quickly remembered himself and returned to his performance of eternal indifference.

Jennifer had nothing to bring along with her that wasn’t already in the pockets of her pinafore, so they made their way back to Grimfern. Simon sat on the horse behind Jennifer and was obliged to hold on to her waist. He was thoroughly mortified.

* * *

[Extract from Gregor Sandys’ experimental jotter, Sunday 9th June 1889]

The damned fungus is a gardener!

No—Imustn’t get ahead of myself. It doesn’t truly understand the light requirements of the Paphiopedilum orchid. It must simply be entwined with the plant’s root system in such a way that it can sense when it is stressed. It is in the fungus’ interest to keep the plant alive, in order to continue drawing nutrients from it. So, when there is too much light, the mycelium closes off the box. Astonishing, yes, but fully explicable by natural science. It protects its precious flower as jealously as it would guard its own life. A biological imperative!

And what an orchid to guard. William Morris could not dream up a more perfectly sinuous specimen. By the ancient law of finders-namers, I shall christen it Paphiopedilum gregorianum. I assume the fungus won’t mind.

To test my theory, I have set up a little experiment. Carefully shaded by a tent of muslin, I have transferred the orchid-mycelium symbiote to a pot under a trellis. At the top of the trellis is a spritzer, and by the orchid’s roots is a miniature bellows. Once the myceliumis settled, I shall blow air across the root system, drying out the substrate and orchid. Will the fungus be spurred into action? Will it mist itself?

For now, I must leave it to acclimatise. Rosie arrives this afternoon. I wish I could show her this orchid—she would die for its colours. And then tomorrow, or maybe next week, the fungus will be put through its paces… And if the mycelium can look after an orchid, I may well be out of a job, what!

* * *

Jenny was a dab-hand with horses. She had no trouble taking Florence the grey mare at a canter through the winding lanes around the village, twisting this way and that through snickets narrowed by June’s green richness. The stubborn horse beneath her had been reluctant at first, but soon they were racing madly and freely together—Florence’s grumpiness lost in the giddiness of speed.

Mr Rievaulx, at the rear, was more like cargo than a passenger. Tense throughout all his body, Jenny noticed that although he kept his hands near her waist where he should have been holding on, he didn’t actually touch her at all. When the shaggy trees of her shortcut trail hung low she would bob down, but Simon could only stammer “I… I… I…” and get a faceful of bower for his hesitation.

They reached the boundary of the Grimfern Estate and Jennifer pulled Florence into a rearing stop. Simon finally grabbed her for dear life while the horse settled. Will, who was serving as doorsman for the afternoon, stuck his head out of the gatehouse, where he had been ‘on guard’ reading a Penny Dreadful. His open jaw sunk back into his neck in surprise at what he saw in real life however—Jennifer’s arrival was apparently more salacious to him than the lurid contents of his periodical. When the horse settled Simon withdrew his gloved hands from Jenny’s waist as if they had been burned.

“Good day, Mr Rievaulx—Jennifer.” Will removed his cap and beamed up at her. “I thought you weren’t coming in today? I told Mr Sandys…”

“Yes, hullo, Will. I’m here now, anyways. Tell you later. Oh, and it looks like there’s moss blocking the gutters.”

Will turned to peer at the roof, confused. As many times as she had been through this gate on foot, Jenny now barely recognised it. She could get used to this lofty vantage point.

“Sort that out, won’t you, William,” Mr Rievaulx muttered, not catching anybody’s gaze, “and get the gate for us. Quickly, now.”

Will fumbled for the latch and swung the gate wide. He stood there staring for just a little bit too long.

“What’s wrong, Will?”

“Nothing! Just that… riding a horse looks well on you, Jenny.”

“Oh naff off, will you?” Jenny said, laughing away the compliment.

“That will be all, William,” said Mr Rievaulx in exasperation.

The post boy replaced his cap and closed the gate. As they headed off up towards the greenhouse, he kicked a stone into some bushes, probably a little harder than he meant to. Then he went back to his reading with a huff.

Jenny kept the mare at a trot as they rose along the sweeping drive. Groundsmen stopped their work to watch her go by—pairs of them, with rakes or shears, small against the rolling expanse of lawn. Jenny felt their gaze, and let it feed her determination. She had always been an oddball to the villagers—a girl of little daintiness, a young woman who refused to partake in the games of coyness and courtship. That is why she and Constance had such a fast friendship, and why the whispers of shame around her death clung to Jennifer also. She caught sight of one worker mutter something to his mate. The other fellow laughed hollowly and leaned on his spade.

Jenny shook herself and geed the horse a little. She couldn’t let herself think about Constance, for fear of losing herself in the grief-rush. She couldn’t let herself think about the snide villagers and groundsmen, either. Not now—not now that she had been elevated over the tattling masses.

They stabled Florence, leaving her with a hearty pitchfork’s worth of hay. Mr Rievaulx let them through the iron gate under its topiary arch to the patio. Jenny had seen this part many times before, with its roses and stone urns, when she had clambered up with Will to swap the mail and laundry. Never before, though, had she crossed beyond the gate. She took care to place her steps squarely on the herringbone bricks, twisting her ankles in odd angles to achieve it. It seemed more proper for a first passage onto new territory not to tread upon the daisy-graced cracks.

Ahead, thick, dark leaves of trees Jenny could not name pushed against countless panes of glass, casting greenish shadows and hiding the interior from view.

“You had better come in, I suppose,” said Mr Rievaulx, pulling at the door’s ornate handle and opening up this crystal box for her.

Jenny was immediately buffeted by heavy, wet heat—the hottest day of Buckinghamshire summer was nothing compared to the steamy atmosphere of Grimfern. She stepped in slowly, mouth agape at the queer forest of wonder—the whole world’s jungles compressed into one vivid grove. Jenny traced a strange path winding through the multicoloured underbrush, finding a large and placid pond bursting with water lilies. All around there were plump, shaggy bushes with flowers of purples and pinks, sprays of vines dripping from overhead walkways, tall palms lolling about above even these, and cream-painted pillars of sinuously wrought iron holding up the ceiling. And oh, that ceiling! Jennifer spun around as she took it all in, her heart rising to burst. A whole house made of windows!

The sky was so big and blue beyond the ceiling. A flock of birds swooped about beyond the roof. She thought of Constance, as she always did at the murmuration of birds, and the huge feeling of beauty in her chest threatened to overflow into grief once more. She abruptly sat herself down on the stone wall around the pond and focused on her boots. There was moss and lichen growing in the gaps between stones. Even these tiny greennesses were precious—with their tiny stalks and dew-drop eyes.

Mr Rievaulx approached her stiffly.

“Did you make all this?” she asked, breathless.

“Gregor did. Mr Sandys, that is. You might say he is quite skilled with a trowel.”

“And then some,” said Jennifer. “It’s… it’s… it’s a whole world. It’s the world. A world-garden in a box.”

Simon looked around the atrium appreciatively. He didn’t seem to disagree. He raised his deep, tight voice to call for Gregor, who called back gruffly from the east wing.

“I think, Miss Finch, you had better meet the great gardener.”

* * *

Gregor had spent the morning prodding and poking his incredible fungus and scribbling down the findings in his jotter with a blade-sharpened pencil. He suspended a muslin canopy over the orchid and its fungal guardian, to shield them from direct sunlight. Then he broke apart the crate and set up a frame over it with a water reservoir and spigot. If the mycelium could moderate the light, could it also manage the orchid’s water intake?

Finding the prodigious gardening abilities of the Sumatran mycelium had given Gregor a mad spark of that determined inspiration which fuelled many of his most outlandish breakthroughs. In his youth, one such spark provided the energy to imagine the most unlikely of graftings, which had won him a plaudit from Kew. Right now, it wasn’t only Kew that he was aiming to impress, but the whole Royal Horticultural Society. In fact—stuff the RHS. They wouldn’t appreciate Gregor’s incredible endeavour. This would impress the Royal Society! Julian Mallory and the RHS could go lick a nettle for all he cared. Gregor had already succeeded in encouraging self-preserving motor function in a fungal specimen. What leaps would be required to develop in it an animal’s instinctive reasoning, or a human’s rationality? At what point could a non-animal be empirically described as ‘conscious’? After scribbling the word repeatedly in his jotter, crossing it out, circling it, and underlining it until his pencil blunted and his page became heavy with lead, he wandered reluctantly over to the small library in the east wing.

It was perhaps generous to refer to it as a library—the book nook was a series of shelves surrounding a floridly carved desk and chair. The moisture of the botanical garden wreaked havoc on the books themselves, which became yellowed and curled and even mouldy within a season of being bought new.

Amongst the musty novels and grizzled encyclopaedias lay a token number of philosophical texts—largely Simon’s purchases. Simon would leaf through these tomes, occasionally giving out an aha! or a fascinating! But Gregor knew they were largely for good show and aesthetic value. Gregor cared not for the great philosophers, even the Greeks. Why digest another man’s pages when you could be writing your own? The Book of Gregor would be written by his own hand. Still, it couldn’t hurt to check what the old boys had come up with regarding matters of the mind.

He had hitched up his trousers and was trying to sound out the title of an Ancient Greek text on the bottom shelf, when Simon’s call came from the atrium. Gregor harrumphed back and waited for him to appear and inevitably scupper his ironclad focus.

When he arrived, Simon’s back was unusually stiff—even for him—and his tie was slightly off-kilter, which was virtually unknown for the strait-laced taxidermist. Gregor withdrew a book at random and let it fall open, so it would seem that he was perusing its contents.

“Got a new project on, Simon, old boy. Trying to get a head-start before Rosalinda gets here. Kindly sod off, won’t you, my love.”

“Under normal circumstances, I would, of course, but, um—”

“Whatever’s the matter with you?” Gregor asked.

“We have a housekeeper.”

“No, we do not.” Gregor snapped the book shut, deciding he was very glad of his prop and resolving to carry a slim volume with him at all times in the future for the purpose. “Grimfern hasn’t had a housekeeper since the house burned down. What’s the point of a housekeeper if one doesn’t have a house?”

“Perhaps she can be the greenhousekeeper, then.” Simon’s usual vocal gravitas deserted him as he squeaked, “Miss Finch!”

A girl with a plain dress and heavy boots emerged from behind an over-weighty clematis, which formed part of the library wall. This was Jennifer—the laundry girl whose absence had caused such a fuss this morning. Her freckled cheeks were rosy and her hair fell in tangles like a hanging fern.

“I could be a groundskeeper, or a gardener, if you like?” she offered with a self-effacing shrug.

“I am the gardener!” Gregor bellowed. It was quite against the natural order of things at Grimfern to depend upon anybody except the residents. Anything Gregor couldn’t do fell to Simon, and vice versa. Bringing in this stranger would ruin the sanctuary of their intense partnership.

“Or anything, really—please, sirs, I really need this job. My father…” The girl had a feisty expression and clenched fists, but tears were welling up in her eyes.

Gregor interrupted to avoid such a breach of protocol. “No, no—stop that. Simon, I think I see now that this is already a fait accompli. On your head be it. Miss Finch—you will keep your duties to the central atrium and the east wing only. I regret deeply that you have already been admitted to the garden. Simon’s compassionate heart has rather got the best of him. I must stress that you are not under any circumstances to enter the west wing, for it is my laboratory, or the basement, for that is Mr Rievaulx’s workshop. Is that clear?”

“Yes, Mr Sandys.”

“I need to lie down for a bit,” sighed Simon, retreating in relief to his underground sanctum where he kept a divan expressly for the purpose.

“And I have much important work to do. You can start with the atrium—we have to get ready for our visitors. Good day to you, Miss.”

With that, Gregor disappeared into his laboratory with an angry flourish. Once out of sight, however, he squeezed the philosophy book tight to him, placing it next to his cloaked experiment. It wouldn’t do to let anybody see the mycelium just yet. Not until he could be sure of its abilities. Rosalinda and Simon, discreet as they were, might mistake the thing for a mere parlour curiosity, which would break Gregor’s heart.

And then there was this accursed Miss Finch, newly admitted to the garden, what of her? She probably wouldn’t understand it, even if she did see it. But the less she knew, the better.

Three

Gregor’s business was plants. It was his parents’ fortune which had provided for the glasshouse on their rambling estate, and it was their ill-fortune which had burned their actual house to the ground. Gregor had been a young man when he watched the conflagration from the safety of the isolated botanical garden. That was the night he inherited the Grimfern Estate, sans manor house. He had left the charred foundations to be reclaimed by the wild woods, and instead developed the garden’s reputation as a centre for botanical research, attracting wealthy and learned individuals from across Europe. Gregor traded successfully in horticultural rarities, which only he had the deftness of touch to nurture in Britain.

Though the garden was decidedly closed to the public, a select cabal of scientists and socialites could correspond with Gregor to arrange an appointment. Of course, very few people had his details in the first place—his address was a valuable commodity amongst the horticultural set in London. This morning—the 9th of June 1889, Whitsun Day—one welcome repeat visitor had made the arduous carriage ride out of the city to visit Gregor and his plant emporium.

“Goodness, this heat, Gregor,” she purred. “Don’t you know how many layers I’m wearing?”

Mrs Rosalinda Smeralda-Bland was a sumptuous woman of continental extraction. Her interest in plants was part aesthetic, part empathetic; since she herself resembled a pomegranate so ripe it was bursting juicily at the seams.

“I’m afraid the heat is required to preserve the most exquisite of the hot-house flowers,” said Gregor, suddenly erupting into a beguiling grin, “yourself the first amongst them.”

Gregor’s accent was showing—his rolled ‘r’s were calligraphic embellishments for his plum-honeyed words. Rosalinda pursed her moist lips and struck him playfully with her fan.

“Oh, I’m always treated well when I come to visit my boys. Where is Simon?”

Gregor called his name, stamping on the brick floor. Soon the baleful figure of Simon emerged from his cellar. He air-kissed Rosalinda with all the solemnity of a Byzantine funeral and stood with his hand on Gregor’s shoulder.

“Simon has just been out for supplies. There’s a man in the village who provides him with pelts and what-not. He came back with rather more than he went out for, in fact.”

Jennifer popped her head out from behind a Camellia japonica and frowned.

“How are you finding that piece you bought, Rosalinda?” Simon drawled, casting a sideways glare at Gregor’s passive barb.

“Oh, she’s just delightful. She has pride of place in the parlour—all my friends love her. Mr Bland of course has a mortal fear of owls”—here she dropped her voice to a jaw-clenched confidence—“but that of course was the primary reason for her purchase.”

Just then, Mr Bland staggered through the conservatory door with a pile of empty hat boxes for his wife to fill with plants. The trio’s easy rapport was destroyed by his presence. Simon removed his hand from Gregor’s shoulder and they stepped apart. He knew—hemustknow—but still. Mr Bland’s excruciating plainness served to accentuate his wife’s zest—a vibrant butterfly shines when stapled to plain card.

“Good afternoon, Mr Sandys, Mr Rievaulx.” He shook their hands without meeting their eyes. “My wife is so looking forward to touring your establishment. She has mentioned it quite a bit. All week in fact—”

“Well then, we’d better start looking around! See you later, Simon.” Gregor kissed the taxidermist on his prominent cheekbone in an act of social defiance. Rosalinda bit her lip, pleasantly scandalised. Mr Bland looked at the floor, which Simon used to make a quick getaway of his own, down to the secrecy of his basement workshop.

Gregor whisked Rosalinda around the central dome of the greenhouse. “We’ve had a lot of new stock in from Nepal, and you’ll just love this season’s chrysanthemums…”

He had become adept at showing his visitors exactly what they were looking for, even if they themselves did not know what that would be. Every bloom was loved and well-cared-for, but not one leaf in this section was sacred. Gregor was an artisan as much as a researcher, and, when required, a salesman beyond even these. Any of his specimens could be parted with for a price.

Soon, Rosalinda had filled her hat boxes with Nepalese rhododendrons, Japanese chrysanthemums, and Gregor’s signature orchids: a variety so frilly and pale they seemed like fanciful splashes of water. Mr Bland, who had to transport the living cargo around this floral warren, was taking a breather. He stood wheezing and still, watching the haughty business of some caged birds of paradise. Rosalinda and Gregor were leaning on the balcony of a gallery which ran around the atrium, looking down at the queer forest of incongruous blossoms.

“That’s quite a haul you have there, Rosalinda,” said Gregor, languid against the banister. “We’ve given poor old Mr Bland quite the run-around.”

“He needs the exercise,” she quipped, “and I need the beauty provided by your botanical prowess. And yet—”

Here she looked far into the impenetrable distance, like Isolde yearning for her Tristan. Gregor saw the wistful sadness on her lovely face and his resolve almost faltered.

“I know you possess wonders that are yet unseen. You have many secrets in your heart, Mr Sandys. And in your laboratory…”

“I don’t allow clients into my laboratory, Rosie,” Gregor mumbled.

“Client? Zut! Which of your clients knows the ins and outs of your practice as well as I? Which of them is more well-read than I on the gardens of Pairi-daeza, or of Lebanon, or of Moorish Spain? Which of them hosted the salon at which the noted botanist first ensnared a budding taxidermist? Really, Gregor, how long have we known each other? How many secrets have we shared? It’s not so much a question of clientele—”

“Alright, what do you want to see?” he snapped but smiled at Rosalinda’s teasing. “One thing, Rosie, I’ll show you one thing in my lab.”

“Then let it be the wildest, most unusual specimen you’re working on. I don’t care about beauty, not for this. I want to see something unimaginable.”

There was, of course, only one experimental pot that would sate her wild inquisitiveness. The pair snuck down a wrought-iron staircase to the ground floor, taking care to not let Rosalinda’s husband catch them escaping. Gregor removed his cravat and used it to blindfold his guest, who was positively thrilled at the gesture. He led her by the hand through an ivied partition into the west wing, where rows of workbenches strewn with soiled books and bizarre plants signalled that this was Gregor’s workshop. Here the smell of soil overpowered the smell of flowers.

Gregor led her over to a bench which was sheltered from the sun by a thick muslin drape. He raised it to bring both of them inside, then trapped them like children in a fabric fortress. The sun bled through the muslin, casting a golden glow. With stifled giggles he removed her blindfold and watched her face, hungry to read her every reaction.

She was initially disgusted with what she saw—this pleased Gregor no end. A shallow glass bowl about a foot in diameter contained an inch of soil and a seething mass of sinews. These tendrils caressed and cocooned a gorgeous orchid, dainty but flushed with colour. Above the bowl on a tripod was a device that would release sugar water when pressed in a certain way. Fungal threads already wound their way up the legs of the tripod and caressed the sluice gate above; spotting this made Gregor squirm. The smell of mould and decay was overpowering.

“You’ll have to explain quickly, Gregor.” Rosalinda was breathing shallowly into her petticoat. “You’ve forgotten that I have a delicate lady’s constitution!”

“Please.” He screwed up his face. “I know you well enough—your curiosity beats your feigned sensibilities.”

She dropped the fluttering act but could not shake a profound dislike for the gelatinous tendrils before her. “Go on, then, what is it? Fungus, no doubt, but why have you trained it up the tripod like an English ivy?”

“That’s just it—I haven’t.” His wild eyes drank in the filmy sheen of his gelatinous glob. “It did that itself. There’s sugar water in the tank which it can use for nourishment. But if it opened the spigot all the way, it would become waterlogged. Now I suppose we shall see if it has learned how to water itself. Watch—”

He took up the miniature bellows that lay beneath the bench and blew dry air across the specimen’s many brandished feelers. This caused dust and spores to rise, which in turn caused Rosalinda to manually close her nostrils. After a short bout of desiccating wind, Gregor stopped pumping. The thin wisps of the fungus, however, continued to jostle as if in a light breeze. The wriggle became concentrated at the spigot of the water tank, and sure enough it turned, allowing a fine rain of sugary dew to fall. Once the thing had had enough, the jostling began again, this time to turn the tap off. Rosalinda looked at the botanist in wonder, but he was still watching his discovery in terrible glee.

“Wherever did you find it?”

“The original mycelium—that’s the word for the fibrous mass of the thing—was taken from an overgrown ruin on Sumatra. It displayed unusual characteristics indicating the transmission of information through itself, but nothing like this. I had to persuade the Sultan that it had hallucinatory properties so he thought I was just extracting it for pleasure. I believe he took some—I hope he wasn’t adversely affected.”

Rosalinda hit him again with her fan.

“When I finally got it back to Blighty it made a concerted effort to remain in its crate. Protecting its orchid, I suspect. And now, it seems, watering it.”

“So it’s… alive?”

“I mean—yes, it’s alive. All fungi are alive, until they’re dead.”

“But is it conscious? Does it know we’re here?” she whispered, as though afraid it could hear them.

“It doesn’t know we’re here. All it knows is water and light, and the absence of those things. Is it conscious? It’s hard to say. Plants grow to face the sun, but does that mean they know where it is? Deciduous trees shed their leaves in autumn—does that mean they understand the calendar? There are carnivorous plants which sense the best time to strike at their prey…”