0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Suddenly Rodney finds himself caught up in an espionage plot, fighting bravely against desperate odds. Then he meets a young girl whose faith touches him deeply, and he discovers a strength to overcome - and the joy to be found in honest faith and real love.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

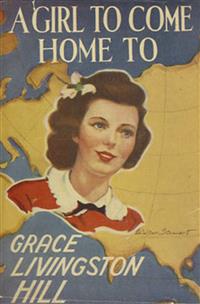

A Girl to Come Home To

by Grace Livingston Hill

First published in 1945

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Chapter 1

World War II Eastern United States

The stars were all out in full force the night that Rodney and Jeremy Graeme came home from the war. Even the faraway ones were peeping eagerly through the distance, trying to impress the world with their existence, showing that they felt it an occasion when their presence should be recognized. And even the near stars had burst out like flowers in the deep blue of the darkness, till they fairly startled the onlooker, rubbing his eyes in wonder if stars had always been so large. It was early evening, scarcely six o’clock, but it seemed so very dark, and the stars so many and so bright.

“It almost seems,” said Jeremy, “as if all the stars we have ever seen since we were born have come out to greet us now that we’ve come home. They’ve all come together. The stars that twinkled when we said our prayers at night when we were little kids, and seemed to smile at us and welcome us into a world that was going to be full of twinkling lights and music and fun. The stars that bent above the creek where we were skating, and seemed to enjoy it as much as we did. The stars that smiled more gently when we drifted down in the old canoe and sang silly love songs, or lay back and grew dreamy with unmade ambitions.”

“Yes,” said Rodney with a grin down at his brother, “the stars that blessed us with a bit of withdrawing when we walked home from church, or a party at night with our best girls. Right, Jerry? There must have been girls somewhere in your life after I left. There’d have been stars for them, too, of course. That’s a swell thought that all those star fellows have sort of ganged up on us for tonight. Nice to think about.”

“It seems an awfully long time ago, though, all those other things happening,” said Jeremy thoughtfully. “Like looking back on one’s self as an infant. After all we’ve been through, I wonder how we’re going to fit into this world we’ve come back to.”

“Yes, I wonder!” said Rodney. “I sure am glad to get back, but I’ve sort of got a feeling every little while that somehow we oughtn’t to have come away till we’d finished the job and had ’em licked thoroughly so they can’t start anything again.”

“Yes, that does haunt you in the back of your mind, but anyway we didn’t ‘come’ away. We were sent, and had to come. They thought we were more important over here.”

“Of course,” said the older brother. “And I’m satisfied, understand. Only somehow there’s a feeling I ought to take hold and do some more over there yet. But I guess that’ll wear off when I really get into this job over here they think is so important.”

“Yes, of course,” said the younger brother. “But there’s this to remember: we aren’t like some of the other fellows. I heard one fellow on the ship complaining the folks over home didn’t understand. They hadn’t any idea what we’ve been through. They’ve been just going on happily having a good time between their good acts of doing a little war work. But our family isn’t like that. Our dad and mother understand. Dad’s never forgotten his own experience in the other war. You can tell from their letters.”

“Yes, of course,” the older brother said, smiling. “Our family has always been an understanding family. But you’re right about this world we’re getting back to, I suspect. For a while it will be like going out to play marbles or hide-and-seek. The trouble is one can’t go out to meet death without growing up. We’ve grown up, and marbles don’t fit us anymore.”

“Sure!” said Jeremy thoughtfully. “We’ll just have to get adjusted to a new world, won’t we? And somehow I don’t see how we’re going to fit anymore. I don’t really have much heart for it all myself, except of course getting back to Dad and Mom and Kathie. But the others will seem like children. Of course you don’t feel that way because you have Jessica. You’ll get married, I suppose, if it really turns out that we get that job they talked about overseas. You planning for a wedding soon, Rod?”

There was a definite silence after that question, and suddenly the younger brother looked up with a question in his eyes. “I didn’t speak out of turn, did I, Rod?” He looked at his brother anxiously. “You and Jessica aren’t on the outs, are you?”

Rodney drew a deep breath and settled back. “Yes, we’re on the outs, bud. Our engagement is all washed up.”

“But Rod! I thought it was all settled. I thought you bought her a ring.”

“Yes, I bought her a ring,” said the older brother with a forlorn little sound like a sigh. Then a pause. “She sent it back to me a year ago today. I guess by now she’s married to the other guy. I don’t know, and I don’t want to know anything more about it. She just wasn’t worth worrying about, I suppose.”

There was a deep silence with only the thunderous rumbling of the train. The younger brother sat and stared straight ahead of him, his startled thoughts taking in, in quick succession, the sharp changes this would make in his idolized brother’s life, the things he knew in a flash must have been being lived down by Rodney all these silent months when they had not been hearing from each other. And then his comprehension dashed back to the beginning again.

“But the ring!” he faltered, thinking back to the bright token that had meant to him the sign of everlasting fidelity, the lovely, peerless jewel that they had all been so proud their Rodney had been able to purchase with his own well-earned money and place upon the lovely finger of the beautiful girl who was his promised bride. “What will you do with the ring?” Jeremy was scarcely aware he was asking another question. He had been merely thinking aloud. Rodney turned toward him with a look almost of anguish, like one who knew this ghastly thing had to be told, and he wanted to get it over with as soon as possible.

“I sold it!” he said gruffly. The brothers’ eyes met and raked each other’s consciousness for full understanding. And in that look Jeremy came to know how it had been, and how it had to be with Rodney. Rodney was four years older, but somehow in that look Jeremy grew up and caught up the separating years, and understood. It did not need words to explain, for Jeremy understood now. Saw how it would have been with him if he were in a like situation.

But after a moment Rodney explained. “At first I wanted to throw it into the sea. But then somehow that didn’t seem right. It wasn’t the ring’s fault, even though it was of no further use to me. Even supposing I should ever find another girl I could trust, which I’m sure I never will, I wouldn’t want to give her a ring that had been dishonored, would I? No, it would never be of any further use to me, or to anybody unless they were strangers to its history. Yet what to do with it I didn’t know. I couldn’t carry it on my person and have it sent back to my mother sometime after I had been killed, to tell a strange story she wouldn’t understand, could I?”

“Then Mom doesn’t know?” asked Jeremy.

“Not unless Jessica has told her, and I doubt if she has. She wouldn’t have the nerve! Though maybe there was some publicity. I don’t know. I haven’t tried to find out. There hasn’t been a word of gossip about it in any of my letters. My friends wouldn’t want to mention it, and any others didn’t bother to write, so I’ve had to work this thing out by myself. After all, it was my problem, and I worked at it part-time between missions. It helped to make me madder at the enemy, and less careful for myself. What was the use when the things I had counted on were gone?

“And what was the ring that I had worked so hard to buy but a costly trinket that nobody wanted? So I found a diamond merchant who gave me a good price for the stone, more than I paid for it, and I was glad to get rid of it.

“That’s the story, Jerry. It had to be told, and there it is. At first I thought I couldn’t come home, where Jessica and I had been so much together, but then it came to me that there was no point in punishing Mom and the rest just because Jessica had played me false. So I’m here, and I only hope I won’t be subjected to too much mention of the whole affair. Jessica, I’m sure, will be out of the picture, thank heaven! She spoke of being married in another part of the country.

“Certainly I never want to lay eyes on her again, of course, and perhaps in due time, with the help of a few more wars, I may forget the humiliation I have suffered. But I don’t want pity, kid. I’m sure you’d understand that.”

“Of course not,” said Jeremy, giving a sorrowful, comprehending look. “But Rod, I don’t see how shecould. She always seemed to be so crazy about you.”

“Well, let’s not go into that. I’ve been through several battles since that thought used to get me,” said Rodney.

“The little vandal!” said Jeremy. “What did she do? Just send the ring back without any letter or explanation?”

“Oh, no, she sent a nice little letter all right, filled with flowery words and flattery, to the effect that she was returning the ring, though she did adore it, because she thought I might want to use it again, and that I had always been so kind and understanding that she was sure I would see that it was a great deal better for her to frankly tell me that she had discovered she didn’t care for me as much as she had supposed; and as she was about to marry an older, more mature man, who was far better off financially than I could ever hope to be, and she wished that I wouldn’t feel too bad about her defection. She closed by saying that she hoped that this wouldn’t be the end, that she and I would always be friends as long as the world lasted. That we had had too much fun together to put an end to it altogether. Words to that effect, said in a flowery style, quoting phrases that had been supposedly dear to us both in the past, showing me plainly that they had never really meant a thing to her but smooth phrases.”

“The little rotten rat!” blurted Jeremy. “I’d like to wring her pretty little false neck for her!”

“Yes, I felt that way for some time, but then I reflected that I didn’t want to even give her that much satisfaction. She isn’t worth so much consideration.”

“Perhaps not,” said Jeremy, “but all the same I’d like to class her with our enemies and let her take her chances with them.”

The older brother gave an appreciative look.

“Thanks, pard!” he said with a wry grin. “Well, enough said. It’s good to know you’ll stand by if an occasion arises.”

“Yes, brother, I’ll stand by,” said Jeremy solemnly, and then after a moment, “And what about Mom and the rest?”

“Oh, they’ll have to be told I suppose, but at least not the first minute. The time may come soon, but probably not tonight.”

There was silence for several minutes, and then Jeremy spoke slowly, speculatively. “Ten to one Mom knows,” he said. “You know she always had a way of sort of thinking out things and knowing beforehand what had happened to us before we even got home.”

“Yes, that’s true. Dad always said it was her seventh sense. That she sort of smelled ’em out ahead of time. Still, I don’t see how she could this. However, it’s all right with me if she has. I guess I can take it. Gosh, I hate to tell her. I hate to be pitied.”

Another long silence, then Jeremy said, “Yes, I know. But I guess you can trust Mother.”

“Yes, of course,” said the older brother, lifting his chin with a brave gesture. “Yes, Mother’s all right. Mother’s wonderful! And it ought to be enough for any fellow to be getting home to her without worrying about some little two-timing brat of a gold-digger.”

Jeremy flashed a quick look at his brother. “Was that what she did? Was it money?”

“Yes, I figured that was what did it. A guy I met in the navy mentioned his name once and said he was just rolling in wealth. Had something to do with the black market he thought, though when I came to question closer, he wouldn’t tell any more. He said he guessed he oughtn’t to have mentioned it. Seems the fellow is an uncle of a buddy of his on his ship, and he was afraid it might get back to him that he had been talking. Well, what difference did it make? She’d thrown me over. Why should I care what for?”

“But Rod, we’re not exactly poverty-stricken. And as for you, Jessica knew Uncle Seymour left you a nice sum. You had a good start in life for a young man.”

“My shekels wouldn’t hold a candle to what a black market man could make now,” Rodney said, grinning.

“No, I suppose not,” said his brother with an answering grin. Then there followed a long silence, the brothers thinking over what had been said. Rodney had perhaps been more confidential with Jeremy than ever before in his life, and the younger brother had a lot to think over.

Rodney had dropped his head back on the seat and closed his eyes, as if the confidence was over for the time being, and Jeremy stared out the window unseeingly. They were not far from home now, another half hour, but it was too dark to notice the changes that might have come in the landscape. Jeremy was interested, after his long absence from his own land, in even an old barn or a dilapidated station they passed. Anything looked good over here, for this was home.

But there were adjustments to be made in the light of what Rodney had just told him. He had come home expecting a wedding soon, and now that was all off, and there was a gloomy settled look of disappointment on the face of the brother who had always been so bright and cheery, so utterly sure of himself, and what he was going to do. Was this thing going to change Rod? How hard that he not only had the memory of war and his terrible experiences at sea, but he had to have this great disappointment, too, this feeling of almost shame—for that is what it had sounded like as Rod told it—that his girl had gone back on him. The girl whose name had been linked with his ever since they had been in high school together. What a rotten deal to give him! Good old Rod! And he had always been so proud of Jessica! Proud of her unusual beauty, proud of her wonderful gold hair, her blue eyes, her long lashes, her grace and charm!

Jeremy searched his own heart and found that for a long time he himself had never cared so much for Jessica. Perhaps it was because she had always treated him like a younger brother, sort of like a little kid, always sending him on errands, asking favors of him, just a sweep of her long lashes and expecting him to do her will, do her errands, give up anything he had that she chose to want, like tickets to ball games. Well, he thought he had conquered those things, because he had been expecting ever since he went overseas that she would sometime soon be his sister-in-law, and he wanted no childish jealousy or hurt feelings to break the beautiful harmony that had always been between his brother and himself. The family must be a unit. And so he had disciplined his feelings until he was all ready to welcome his new-to-be sister with a brotherly kiss.

But now that was out! And Mom didn’t know anything about it yet? Or did she? Could a thing like that fail to reach their mother? If she didn’t know, how would she take it? Had she been fond of Jessica? He tried to think back. He could dimly remember a sigh now and then, a shadow on her placid brow. When was that? Could that have been when Rod first began to go with Jessica? But Mom had later seemed to be quite fond of Jessica, hadn’t she? Jeremy couldn’t quite remember. He had been more engrossed in himself at that time. About then was when he got that crush on Beryl Sanderson, the banker’s daughter. Of course that was ridiculous. He, the son of a quiet farmer, living outside the village, on a staid old farm that had been in the family for over a hundred years, without any of the frills and fancies that the modern homes had. And she the daughter of a most influential banker, who lived in a great gray stone mansion, went to private schools, then away to a great college, dressed with expensive simplicity, and never even looked his way. Beryl Sanderson! Even now the memory of her stirred his thoughts, although he hadn’t been pondering on her at all, he was sure, since he went away to war. Well, that was that, and he wasn’t mooning around about any of his childhood fancies. He had a big job to do for his country, and there wasn’t time for anything else then.

Suddenly Rodney broke the silence. “How about you, kid? Did you pick up some pretty girl across seas, or was there a girl you left behind you? Come, out with it, and let us know where we both stand now that we’re getting home.”

Jeremy grinned. “No girl!” he said.

“No kidding?” said the older brother, turning his keen eyes a bit anxiously toward the younger man, with a pleasant recognition of the goodly countenance he wore, his fine physique, his strong, dependable face. There was nothing of which to be ashamed in that brother.

“No kidding,” said Jeremy soberly. “Not after the line of talk Mom gave me before I went away. She didn’t exactly hold you up as a horrible example of one who had got himself engaged before time, but she did warn me that it was a great deal better to wait for big decisions like that till one was matured enough to be sure.”

“Hm! Yes, well maybe Mom felt a little uncertain about what I’d done, though she never batted an eye about it. Of course I went away so soon after Jessica and I thrashed things out, and Mom was always fair. She never jumped to conclusions nor antagonized one of us. Probably she didn’t want to have me go away with any unpleasantness between us. She took her worries, if she had any about us, to God. She was that way. She had a wonderful trust that God could and would work any thing out that she couldn’t manage. Mom was wonderful that way. It somehow strengthened me a couple of times when I had a close call, just to remember that Mom was probably on her knees putting a wall of her prayers around me, maybe right at that time.”

“Yes, she’s been a wonderful mom,” said Jeremy thoughtfully. “That’s why I don’t want anything to upset her now. I gotta go slow and let her know I haven’t got away from her teaching. But say, aren’t we coming into our station? Isn’t that the old Clark place? Yes, it is. Now it won’t be long before we’re home. Boy, but I’m hungering for a sight of the old house and Mom and Dad and Kathie and even old Hetty. Won’t it be good to eat some of her cooking again? I’m hungry enough to eat a bear.”

“Here, too,” said Rodney, looking eagerly out the window. “But a bear wouldn’t be in it compared with Hetty’s fried chicken. Nobody ever fried chicken to beat old Hetty. Maybe we ought to have let ’em know we were coming. It takes time to go out and kill a chicken and cook it.”

“Have you forgotten, brother, that they have an ice plant in the cellar? Ten to one Mom’s had chickens galore, frozen and ready to fry, just in case. You know Mom never got caught asleep. She’s probably been getting ready for this supper for the last two months. She won’t be caught napping.”

“No,” said the older brother with solemn shining light in his eyes. “Well, here’s our station. Shall we go? It’s time to get our luggage in hand.”

“Here, I’ll reach that bag, Rod. You oughtn’t to be straining that shoulder of yours, remember. You don’t want to go back to the hospital again, you know.”

And so, laughing, kidding, eager, they arose and gathering their effects, trooped out to the platform.

Casting a quick glance about, they made a dash toward the upper end of the station, and using the tactics known to them of old in their school days, they escaped meeting the crowd that usually assembled around an arriving train. They cut across a vacant lot and so were not detained but strode on down the country road toward their home. That was where they desired above all things to be as rapidly as possible. That was what they had come across the ocean for. Mother and home were like heaven in their thoughts, and at present there was no one they knew of by whom they were willing to be delayed one extra minute.

They were unaware, as they hurried along with great strides, of the eyes of some who saw them as they dashed around the end of the station, and pointed them out, questioned who they were. For though the uniforms of servicemen were numerous, in that town as well as in others, they shone out with their gold braid and brass buttons and attracted attention as they passed under the station lights.

“Well, if I didn’t know that man was overseas in a hospital, I’d say that was Rodney Graeme,” said one girl stretching her neck to peer down the platform behind her. “He walks just as Rod did.”

“You’re dreaming,” said another. “Rodney Graeme has been overseas for four years. Besides, there are two of them, Jess. Which one did you think looked like Rod?”

“The one on the right,” said the first girl. “I tell you he walks just like Rod.”

“I guess that’s wishful thinking,” said Emma Galt, an older girl with a sour mouth, a sharp tongue, and a hateful glance.

“That other one might be Rod’s younger brother, Jerry,” said Garetha Sloan.

“Nonsense! Jerry wasn’t as tall as Rod; he was only a kid in high school when Rod went away.”

“You seem greatly interested for a married woman, Jess,” sneered Emma Galt.

“Really!” said Jessica. “Is your idea of a married woman one who forgets all her old friends?”

But out upon the highway the two brothers made great progress, striding along.

“Well, we beat ’em to it all right,” said Jeremy.

“Okay! That’s all right with me,” said his brother. “I’ll take my old comrades later. Just now I want to get home and see Mom. I didn’t notice who they were, did you?”

“No, I didn’t wait to identify anybody but old Ben, the stationmaster. He looked hale and hearty. There were a bunch of girls, or women, headed toward the drugstore, but I didn’t stop to see if I knew them. I certainly am glad we escaped. I don’t want to be gushed over.”

“Well, maybe we’ve escaped notice. You can’t always tell. We’ll see later,” said Rodney. “But there’s the end gable of the house around the bend, and the old elm still standing. I was afraid some storm might have destroyed it. Somehow I forget that they haven’t had falling bombs over here. It looks wonderful to see the old places all intact. And a light on our front porch. Good to see houses and trees after so much sea. And isn’t that our cow, old Taffy, in the pasture by the barn?”

“It sure is,” said Jeremy excitedly, “and my horse, Prince! Oh boy! We’re home at last!”

They did the last few laps almost on a run and went storming up the front steps to meet the mother who according to her late afternoon custom had been shadowing the window, looking toward the road by which they would have to come if they ever came back. Not that she was exactly expecting them, but it seemed she was not content to let the twilight settle down for the night without always taking a last glimpse up the road as if they might be coming yet before she was content to sleep.

In an instant she was in their big strong arms, almost smothered with their kisses, big fellows as they were.

“Mom! Oh, Mom!” they said and then embraced her again, both of them together, till she had to hold them off and study them to tell which was which.

“My babies! My babies grown into great men, both of you! And both of you come back to me at once! Am I dreaming, or is this real?”

She passed her frail, trembling hand over eyes that had grown weary watching out the window all these months for her lads.

“This is real, Mom!” said Jeremy, and he hugged her again. “And where’s Dad? Don’t tell me he’s gone to the village! We can’t wait to see him.”

“No, he’s here somewhere,” said the mother’s voice, full of sweet motherly joy. “He just got back from bringing Kathleen from her day at the hospital, nursing. He went out to milk the cow. Kathie, oh, Kathie! Father! Where are you? The boys have come!”

There was a rush down the stairs, and the pretty Kathleen sister was among them, and the kindly father, beaming upon them all. It was a wonderful time. And good old Hetty came in for her share of greeting, too.

And then the boys hung their coats and caps up on the hall rack, in all the glory of gold braid and decorations, dumped their baggage on the hall table and chair, and went to the big living room where the father had already started a blaze in the ever-ready fireplace that was always prepared for the match to bring good cheer.

Then as they sat there talking, just looking at one another—even old Hetty having a part of the moment—smiling, beaming joy to one another, somehow all the terrible impressions, so indelibly graven in the consciousness of those fighters who had returned, were somehow softened, gentled, comforted by the sight and sound of beloved faces, precious voices, till for the time the past terrible years were erased. It seemed almost like a look into a future where heaven would wipe out the sorrows of earth.

Then, softly, old Hetty slipped out into the kitchen. She knew what to do, even if Mrs. Graeme had not given that warning look. So many times, dark days, when there had come no expected letters, and news was scarce and bad when it did come, these two good women had brightened the darkness by making plans of what they would do, when, and if, the boys did come suddenly, unexpectedly.

Hetty hurried to the freezing plant and got out her chickens. All the children home now, all the family together at last. And Hetty was as happy over the fact as any of the family, for they were her family, the only family she had left anymore.

And presently there was the sweet aroma of frying chicken, a whiff of baking biscuits at the brief opening of the oven door, the fragrant tang of applesauce cooking. Oh, it was going to be a good supper, if it was hastily gotten together. There would be also mashed potatoes and rich brown gravy, Hetty’s gravy, they knew of old. And there were boiling onions, turnips adding to the perfume. Celery and pickles. They could think it all out in anticipation, and Mother Graeme could smile and know that all was going on as she had planned. Little lima beans. Her nose was sensitive to each new smell. There would be coffee by and by, and there was a tempting lemon meringue pie, the kind the boys loved, in the cold pantry. The boys would not be missing anything of the old home they loved.

They had asked about the horse and the cow and the dogs, the latter even now lying adoringly at the feet of their returned masters, wriggling in joy over their coming.

They had heard a little of the welfare of near neighbors, a few happenings in the village, the passing of an invalid, the sudden death of a fine old citizen, but by common consent there had been no mention yet of the group of young people who had been used to almost infest the house at one time, when the boys were at home before the war. Of course many of the men and a few of the girls were in the service, somewhere, and there was a shadow of sadness that no one was quite willing to bring upon their sweet converse, in this great time of joy. Jeremy, sitting quietly, watching his mother’s sweet, happy face, suddenly realized that she had not ventured to tell them about any of their old friends and comrades, and he wondered again if she knew what had befallen Rodney. He wished in his heart that the matter might not have to be mentioned, at least not that night. There would be time enough for the shadow of a blighting disappointment to one of their number, later, but not tonight. Not to dim the first homecoming. They were there, just themselves. It was almost as they used to be before they grew up, when they were a family, simple and whole. Oh, that it might be that way for at least one more night before any revelations were made that might darken the picture!

He gave a quick look toward Rodney, sitting so quietly there watching his mother. Was Rod wondering about the same things? Of course he was. Somehow he and Rod always seemed to have much the same reactions to matters of moment. And this surely must have been a matter of moment to Rod.

Good old Rod! These first few days might be going to be tough for him. He must be on hand to help out if any occasion for help should present itself. People were so dumb. There were always nosy ones who asked foolish prying questions and would need to be turned off with a laugh, or silence. A brother could perhaps do a lot.

It was just then it happened.

The blessing had been asked. That seemed this time such a special joy to be thanking God for bringing them all together again. Father had served them all heaping plates of the tempting food, and Rod had just put the first mouthful in his mouth. Jeremy watched him do it. And then the doorbell rang, followed by the sound of the turning doorknob, the opening of the big front door, the entrance of several feet, the click of girls’ heels on the hall floor, just as it used to be in the past years so many times. For all their young friends always felt so much at home in their home. But oh, why couldn’t they have waited just this one night and let the home folks have their first inning? Just this first night!

A clatter and chatter of young voice, as Kathleen sprang up and hurried into the hall.

“Oh, there you are, Kathleen,” said a loud, clear voice that Jeremy knew instantly was Jessica’s. “Oh, you’re eating dinner, aren’t you? Never mind, we’ll come right out and sit with you the way we’ve always done. No, don’t turn on the light in the living room, we’ll come right out. Of course we’ve had our dinners before we came, but we simply can’t waste a minute, and no, we won’t hold you up. I know you must be hungry—”

Jeremy’s quick glance went to Rodney’s face, turned suddenly angry and frowning. Yes, he had recognized the voice. His reaction was unmistakable.

In one motion as it were, Rodney swept his knife and fork and napkin and plate from the table as he sprang stealthily to his feet and bolted for the pantry door, carrying with him all evidences of his former presence at the table. Only his mute napkin ring remained to show there had been another sitting there at the right hand of Mother Graeme. Then quickly, quite unobtrusively, the mother’s hand went out and covered that napkin ring, drawing it close to the other side of the coffeepot, entirely out of sight from the door into the hall by which the bevy of guests seemed about to enter. It was then that Jeremy came to himself and realized that this was his opportunity. He swung to his feet and grasped the chair that stood by his side where his brother had been sitting, giving it a quick twist, and placing it innocently off at one side, where any unsuspecting person might sit without noticing that it had but a moment before been a part of the family circle of diners.

Jeremy came forward courteously and met the guests as they entered, ahead of the disturbed Kathleen, who had done her best to turn them aside and failed. But no one would ever have suspected that Jeremy was playing a graceful part, or that he was at all anxious about the present situation. Rodney was definitely out of the picture, that was all that mattered. The pantry door was closed, and there was not even a shadow of the passing of a blue coat with brass buttons, gold braid, and ribbon decorations.

Jeremy glanced at his mother, but she was coolly welcoming the guests, seating them around the room, not saying a word about Rodney’s absence. Perhaps she hadn’t even noticed yet that he was gone. But you never could tell. Mother was a marvelous actress.

Chapter 2

Out on the road going slowly by, two old men were jogging along, as much as an ancient Ford could be said to jog, even in war times, and as they passed the car standing in front of the Graeme house, they even slowed down their war jog and stared at it as they were passing.

“Ain’t that the car Marcella Ashby bought off that Ty Wardlow jest afore he left fer overseas? Seems like there ain’t another one jest that make an’ color in these parts. And I seen her driving by awhile ago with Emma Galt an’ Garethy Sloan, an’ another gal. It looked very much like that highflier who married that old gray-headed ripsnorter of a so-called stockbroker from the West, her that useta be Jessica Downs. Poor old Widow Downs done her best by that gal, but she was a chip off the old block, I guess, and couldn’t get by with that temper’ment she inherited from that flighty ma of hers an’ her good-for-nothin’ pa, Wiley Downs. He was jes’ naturally a cussed young’un from a three-year-old up, when they all thought he was so sweet and cute. Well, he was cute all right. I never did see no sweetness about him though, did you Tully?”

“Not so’s you’d notice it,” answered Tully glumly. “I know he was anythin’ but sweet when I knowed him in school, and I guess his teachers all felt the same way. And that Jessica, she had every one of his traits, including that washed-out yella hair that she flung around sa proudly, ’zif she was the only one who had any. Oh, she was sorta pretty, I’ll admit, but she had sly eyes, and I always wondered how it was that Rod Graeme ever took up with her. I sort of figured that his pop an’ mom was almost glad ta let him go to war jesta get him away from that little gold-digger. Well, she does seem like a gold-digger, doesn’t she? How she shelved Rod Graeme and took up with an old man just because he was said to be rollin’ in wealth.”

“Oh, she’s a gold-digger all right, Tully,” said Jeff Springer, turning out for the car they had just been discussing. “They do say that old guy, Carver De Groot, is rich as they make ’em. Ur leastways that’s the talk. Though I’m wonderin’ what she came back here fer, if that was her in that car with the other gals. I heard tell it was some likely that the Graeme boys might be comin’ home soon on a furlough.”

“Yep,” said Tully. “They hev. I seen ’em jest a little while ago. They got in on the late train and shied off across the meadow as if they was tryin’ to escape notice. Beats all how shy some o’ them heroes are.”

“Well, mebbe the gals seen ’em,” said Jeff, “an’ they’ve come here to find out if it’s so.”

There weren’t many in the town who could beat Jeff and Tully figuring out what had happened and what people were going to do about it.

“Well, I don’t see what she’d wantta come back here fer,” said Tully thoughtfully. “She’s married all righty, fer I heard that Marcella Ashby went out to the weddin’, an’ it ain’t so long ago, neither.”

“Yep. But then, there’s such a thing as di-vorces, ya know.”

“Shucks!” said Tully. “No gal brought up in this here town would think about gettin’ a di-vorce. Why, it ain’t considered respectablehere.”

“Well, you needn’t tell me that gal Jessica would ever stop anythin’ she wanted ta do fer respectability’s sake. It ain’t in her.”

“Mebbe not,” said Tully speculatively, “but it would any of those Graemes. You know that, Jeff.”

“Yes, I s’pose so,” reflected Jeff, “that is, of course, Mom and Pop Graeme would feel that way. But that ain’t sayin’ the boys would feel that way now. They’ve been ta war, ya know, an’ they do say that war changes men a whole lot. You can’t jus’ say fer sure them Graeme boys feels that way now, ya know.”

“It may be so,” said Tully unbelievingly, “but I don’t believe it. I’ve knowed them Graeme boys since little up, an’ I never saw a look or an act that would lead me ta believe they would think a di-vorce would be right. Not them with their bringin’ up. Not them with a father an’ a mother like they got.”

“Well, that’s so, too,” said Jeff thoughtfully. “There’s a great deal in what’s before you. Your forebears mean a whole lot, even in these days. Well, mebbe you’re right! But if that’s so I can’t figger out what that ripsnorter of a gal has gone there fer.”

“Look here now,” said Tully protestingly, “I didn’t say nothin’ about that highflier gal bein’ against di-vorce, did I? She’d prob’ly befer it, I s’pose, but that ain’t sayin’ what she could do about it, bein’ as one of the parties was a Graeme.”

“Well, I hope yer right. I sure do, Tully! It sure would be a contest worth watchin’, and I’m somehow bettin’ on the Graemes my own self, if you ast me. I sure hope I’m right.”

They drove on down the highway, and their voices were lost in the distance.

But inside the Graeme house the contest had already begun.

It was such a pity that Jeff and Tully couldn’t have been present to see the start.

It was Jessica who opened the first round, with a quick glance around the table, taking in the place where Rodney should have been and wasn’t, and not even a napkin ring in sight to mark where he had been.

Her eyes came back quickly to Mother Graeme’s face with a quick suspicious glance. She had always felt that there was not full harmony between herself and Mother Graeme even in the days when she was the acknowledged fiancée of Rodney and supposed to be under the advantage of a blessing and the full acquiescence of his parents. She had none of her own to worry about. Just the one quick glance, searching to see if the mother had somehow managed to spirit away the desirable son in the brief space of time. Then her face melted into a sweet, tender look, for she was very versatile and well knew what kind of a look she should put on to deceive these elect people.

“Oh, dear Mother Graeme!” she said tenderly, meltingly. “It’s so good to get back to you. I have come to believe that there is no mother in the whole wide world as good and dear as you are.”

Mother Graeme looked at her with an inscrutable, unbelieving smile that showed this false girl’s words had not gone even skin deep into her heart. But even her son Jeremy couldn’t be sure just what his mother felt about it when he saw.

“There are a great many mothers in the world, Jessie. You haven’t been away long enough to have seen them all, child.” And then Mrs. Graeme turned away and greeted the other girls graciously.

Mom is a perfect lady even though she’s never been much out of Riverton in her life, decided Jeremy as he watched the quiet poise of his lady-mother. And then he noted that her brief acceptance of the gushing compliment had been enough to put the showy admiration out of running, and Jessica turned quickly to her next interest, which was really what she had come for. It began with another quick survey of the table, dwelling on each vacancy where another might have sat, and then she addressed a remark to the whole table. “But where is Rodney?” she asked, letting her eyes touch each face tentatively and coming back decisively to Jeremy. “I was told that he had come home also. Surely he hasn’t left already?”

Jeremy caught the question midway before anyone else could answer, the way he used to snatch the football out of the very teeth of the enemy when interference hadn’t been suspected from his direction.

“Rod had to go out,” he said quite casually, as if it were a thing to be expected and not at all as if he were apologizing for his absence. And he noted that their mother did not look astonished at his words, and not even Kathleen seemed surprised. Strange. Even his father, after a quick sharp look at Jeremy, went right ahead with his eating and kept his genial family atmosphere intact. He had a great family, Jeremy reflected. And oh, but they must surely know that something was wrong. Didn’t they know that Jessica had married somebody else? Or hadn’t she married him yet? Maybe she didn’t get married. Maybe she had got over that and had come out after Rod again. Well, if she had, he personally would devote himself to seeing that she did not get him. After what she had done to Rod, she was less worthy than he had thought her long ago, not fit for such a prince as his brother. He would keep out of this as far as he could, but if it came to a showdown he would go out for Rod in a big way and save him, even from himself, if she should prove canny enough to lead him so far afield as that.

So Jeremy devoted himself to the other girls, asking them questions about their families and what they had been doing for the war during the years of his own absence overseas.

But presently, as Rodney did not appear and time went on while Jessica watched the younger brother, she became quite intrigued with him and broke into his conversation with vivacity. “Do you know, Jerry, you’ve quite developed,” she said patronizingly. “You’re really a man now, aren’t you?” And she lifted her eyes with that long appeal from under golden lashes that he used to watch her give to his older brother and wonder at so long ago. It fairly sickened him now, the memory of it.

He grinned his slow, indifferent grin. “Well, I guess that’s what was intended I should be, wasn’t it?” he said. And then he turned to his sister and said, “By the way, Kath, we met an old crush of yours in New York as we came through, Richard Macloud. He asked after you and wanted to be remembered. He’s going back in a few days now and is slated for some big job, the powers-that-be aren’t saying what just yet.”

Jessica gave full attention to Jeremy during this brief conversation and took a hand at once.

“Do you know, Jerry, you look very much like Rod. I hadn’t noticed before, but of course now that you’re older, the resemblance is very marked. You’re even taller than he is, aren’t you?”

“Oh no, he’s an inch and a half taller,” the younger brother answered with a gleam of amusement. But he did not further pursue the subject. Instead he turned to his mother and began to ask questions about her old neighbors, women his mother’s age who used to give him cookies when he was a child. He told one or two amusing stories of things that happened long ago.

Jessica was watching him and deciding that when his brother was not present there would at least be Jerry, and he really seemed to be worthwhile. In fact anybody in uniform was interesting to Jessica.