Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IMM Lifestyle Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

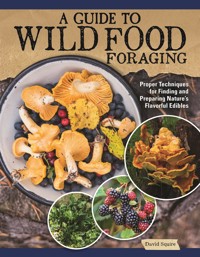

The benefits of foraging for food are far and wide. Whether you're looking for ways to become more self-sufficient, save money, or develop healthier habits, A Guide to Wild Food Foraging is an extensive on-the-go directory of more than 100 profiles for wild plants, herbs, fruits, nuts, mushrooms, seaweeds, and shellfish. Each profile provides tips on identification, seasonality, location, what and when to harvest, and how to prepare and use them in delicious recipes. Most of these foods are within reach -- however, you've got to know what you're looking for and where to go and when. This compact field guide has all the information you need alongside new, high-quality photographs and illustrations to help you identify a wholesome and natural food store, all for free. Forage fresh, local foods so you can eat better, save money, learn a useful survival skill, and have fun in the process!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 185

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published 2023—IMM Lifestyle Books, an imprint of

Fox Chapel Publishing

903 Square Street,

Mount Joy, PA 17552

www.FoxChapelPublishing.com

© 2023 by David Squire and Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc.

Portions of A Guide to Wild Food Foraging (2023) are taken from Self-Sufficiency: Foraging for Wild Foods (2016), published by IMM Lifestyle Books, an imprint of Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Fox Chapel Publishing.

Print ISBN 978-1-5048-0135-5ISBN 978-1-6374-1285-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023934247

We are always looking for talented authors. To submit an idea, please send a brief inquiry to [email protected].

Contents

Introduction

Edible Wild Plants

Popular Wayside Kitchen Herbs

Wild Fruits

Wild Nuts

Mushrooms, Truffles, and Other Edible Fungi

Seaweeds

Shellfish

Glossary

Photo Credits

About the Author

Introduction

Today, most Western countries get their food from tenuous supply chains steeped in strict financial directives rather than from local farms and market gardens. This reliance on larger social and economic systems has led to both rising costs and empty shelves. Rather than accept this trend, many people have realized that self-reliant options are both cheaper and healthier. By becoming a forager—as well as perhaps starting to grow some of your own fruits and vegetables—you will be countering this trend and getting back to the basics of life.

Humans have a long history of foraging. It is impossible to know exactly when, but it certainly began in Africa among our bipedal ancestors, long before the successful exodus of our species into other parts of the world some 80,000 years ago. Later, hunter-gatherers in groups of 10 to 50 were adept at living off the land, surviving on animals they hunted, as well as eating leaves, berries, roots, fruits, and nuts. They wandered the land in search of seasonal food, sometimes following migratory herds, while coastal peoples used the resources offered by the sea.

Foraging can either be the first step in your journey or something you do for fun. But once you realize how simple and satisfying finding and cooking your own food can be, it’s easy to find other ways to make your own resources, whether that’s baking bread, sewing clothes, or raising animals. Foraging can be a great hobby or way of life because you get to soak up the outdoors, learn more about nature, and get nutritious foods at the end. It’s time to take your first step!

Types of Foraged Foods

This forager’s handbook is organized to enable readers to gain instant information. The following pages provide an extensive directory of plants (and some shellfish) that can be foraged. Over 100 species, both wild and escapees from gardens, are included, along with tips on identification, where to find them, what and when to harvest, and how to prepare and use what you find. It is divided into seven parts:

•Edible wild plants, include Chickweed, Dandelions, and Stinging Nettles, which are often the bane of gardeners. However, these are typically the ancestors of most vegetables used in the kitchen today. Others can easily swap out the greens used in salads and other dishes for a more robust flavor.

•Popular wayside kitchen herbs are often escapees from earlier herb gardens. These include Caraway, Fennel, and Spearmint. Foraging for these wild varieties provide you with fresh ingredients for your spice rack.

•Wild fruits can still be found in the wild, although many are widely grown as cultivated fruits. These include Blackcurrants, Cranberries, and Gooseberries. Unlike in supermarkets, these fruits are time-dependent, smaller, and typically easier to bruise. But they are a much sweeter reward!

•Wild nuts, borne by trees such as Beech, Hazel, and Oak, are edible and collectable. Being able to identify the tree is as important as knowing the fruit in this case. You might also see them growing in hedgerows.

•Mushrooms, truffles, and other edible fungi can be gathered and eaten. Most grow at soil-level, some on trees, and a few underground. For safety’s sake, careful identification of all fungi is absolutely necessary.

•Seaweeds are gathered along shorelines, or just beneath low water, and provide highly nutritious meals. Though less common today, this was once a typical resource for our ancestors, and they are surprisingly versatile.

•Shellfish, including Clams, Cockles, and Winkles, can be collected from the wild. While they are the outlier in this group, shellfish are a delight to discover along the coast and incorporate into meals.

Foraging Code

These simple guidelines will make a big difference to plant life in your area.

•Do not strip plants of all their leaves, fruits, or nuts. Gather a few leaves, fruits, or nuts from each plant. Use a knife or scissors to remove them cleanly. Harvest fungi by carefully twisting the stem and then pulling slightly.

•Do not remove flowers from annual or biennial plants as the plant relies on these parts to produce new plants and fruits for the following year.

•Do not dig up plants—it’s illegal.

• When searching for a plant, do not trample over surrounding plants as you may destroy them.

• Be aware that many species of plants are endangered and rare. Gather only those that you know grow in abundance, and do not over-forage. Leave most plants where you find them to benefit wild animals and insects.

The Use of Common and Botanical Names

Plants are arranged in alphabetical order according to their most popular common name within each chapter with the botanical name following. Additionally, because plants (and shellfish) are often native to wide areas of the world, they may have gathered many more common names, which are also listed. Therefore, if you only know the common name of a particular plant or shellfish, you will be able to find it in the index and then establish where it is described and illustrated. Additionally, where earlier botanical names are still used, these will be included as well—a great help where plants are known and identified through earlier floras and gardening books.

Most native plants have a multitude of common names but, surprisingly, coastal plants like Sea Purslane have fewer variations than plants that populate inland habitats. It is significant that plants notorious for their invasive habits, such as Ground Elder, have an abundance of common names throughout their habitats. Check your local offices for natural resources (including websites) to see if there are invasive species that they encourage foragers to pick. This way, you can eat delicious food while helping wildlife thrive!

Plant Conservation

The need to conserve and protect native plants for future generations is a responsibility we must all take seriously. Each year, hundreds of species of wild plants around the world are lost to us through habitat loss, greed on the part of some plant collectors, and ignorance. Whatever the cause, this trend needs to be halted. This book will help you identify plants and teach the proper method to forage them, but please do your research before you start foraging. Laws, ecosystems, and communities vary around the world, meaning it’s best to know as much as possible so you don’t contribute to the problem.

There are a number of places to forage for plants that may not initially occur to you. Apart from local fields, roadsides, and hedges, many other manmade places provide homes to plants. Towpaths along canals dug centuries ago are full of plants, while disused railways provide not only footpaths and cycle trails but also have become ribbons of flourishing plant life. Banking alongside highways also gives protection to plants, but plants along busy roads cannot be foraged for obvious reasons—the dangers of pollution and fast-moving traffic.

Correct Identification

It is essential to know precisely what you are gathering to avoid poisonous plants, and this applies equally to leafy plants as well as to fungi. Therefore, always be certain about the plants you gather and, if in doubt, leave them alone.

Correctly identifying and gathering plants are skills that take time to acquire. Where to look, the time of year the plants are available, and what parts to gather and eat safely are the main questions asked by foragers. But there are also issues of legality that need to be addressed when collecting plants from the wild (see here).

Try to begin foraging with someone who knows what they are doing; learning by observing on the spot with a knowledgeable guide is the best way to acquire safe foraging skills.

Foraging allows you to find your favorite snacks without going to the supermarket.

Questions of Legality

In many countries, wild plants are protected by the law and uprooting native plants is illegal, unless permission is first gained from the landowner or occupier. Additionally, permission is especially required to forage for wild plants in nature reserves, in national parks, on land owned by national land organizations, and on land owned by military establishments.

Wayside plants have long escaped the legality question and foragers are usually free to remove (in moderate amounts) flowers, leaves, fruits (berries and nuts), and fungi from verges and banks alongside town and country roads. Path edges can also be legally foraged.

Remember that foraging just a few plants for your own personal use is usually not a problem, but creating an industry from your gathering is questionable, and you would certainly need permission from the landowner or occupier.

Occasionally, you will come across signs that says, “Trespassers will be prosecuted.” The intentions and liabilities of such signs vary from one country to another, and it has been suggested that they are meaningless in law unless actual damage is committed. However, to avoid problems arising needlessly, gain permission before foraging on private land. Always ask yourself if the land belonged to you, would you want people walking over it without permission?

After Gathering

Apart from identifying and gathering plants safely, getting them home intact requires care. Leaves need a wide basket that does not constrict them. Berries and nuts, however, need containers that can be closed to prevent them spilling and rolling out.

Cover your basket to prevent the sun and wind from drying your gatherings. Wash and dry leaves (if dirty) as soon as you get them home. Place them in a cool shaded room, away from direct and strong sunlight. Some plants and fruits do not require washing, and this is explained in the text for each plant.

Ensuring Plants Are Clean

There are many ways that wild plants can become contaminated, so take care:

• Plants alongside roads are frequently coated by gasoline and diesel fumes.

•Wild animals and dogs are inclined to urinate on easily reached plants. Large-leaved plants alongside footpaths are especially at risk from dogs.

•Chemical sprays can contaminate wild plants that grow close to crops. Increasingly, however, farmers are leaving wider areas around cultivated crops to encourage wildlife—especially bees and other insects.

Edible Wild Plants

The major wild plants for foraging are represented here. Some are becoming rare in the wild even though they’ve been widely and intensively cultivated for centuries. When foraging, treat these rarer species—and all plants for that matter—with respect and restraint.

Among the wild plants fit for foraging are the ancestors of many of our modern-day vegetables. One of these is Wild Cabbage (see here); over several centuries and with careful selection by seed companies, it has yielded brassicas as diverse as Brussels Sprouts and Cauliflowers, as well as Cabbages, Kohlrabi, and Broccoli. Similarly, Spinach (see here) has left a legacy of vegetables, some with large and nutrition-packed swollen roots for feeding cattle, others useful for processing into sugar, as well as succulent and richly colorful roots for adding to salads.

In earlier centuries, because of their value as food crops, many native European plants were introduced to other countries by settlers. Most plants survived and flourished in these new habitats and, in some cases, were too successful. In New Zealand, for instance, introduced Watercress has become a serious problem when it blocks waterways.

Asparagus

(Asparagus officinalis)

Also known as: Common Asparagus, Wild Asparagus

A delicious and distinctive perennial with spreading roots that allow it to produce new stems each year. There are two forms and only the upright one, growing up to about 5' (1.5m), is abundant enough to be gathered. Its stiff stems are generously clad in needle-like cladodes—botanically speaking, flattened leaf-like stems—and from a distance have a fern-like appearance. Male flowers (yellow, tinged red at base) and female (yellow to white-green) are usually borne on separate plants from early to late summer. Round, red berries about ¼" (6mm) wide appear slightly later.

The upright form (A. o. ssp. officinalis) is native to the warmer parts of Europe, Asia, and North Africa, and is naturalized in all of the United States. It has been introduced into many other countries for cultivation as a food plant, from where it has escaped.

You’ll find it: In grassy areas, especially in coastal regions, on cliffs or in dunes, and where the soil is light and well drained.

Spears: Edible parts of asparagus are the spear-like young shoots that appear in spring and through early or mid-summer. Asparagus in the wild is not so large and prolific as that grown in vegetable gardens that can be cut when about 9" (23cm) high.

Harvesting the spears: Only harvest in areas where there is a plentiful supply of spears (it is scarce in some areas). Where there are sufficient spears to harvest, use a long-bladed knife to cut the base just below soil-level.

Using the spears: Wash and recut the bases, then either steam or poach in water until just tender. Asparagus spears are versatile in the kitchen and can be used in many dishes, including fondues, risottos, quiches, soups, and salads. Asparagus is also delicious steamed and served simply, either drizzled with melted butter, a vinaigrette, or a hollandaise sauce.

Chickweed

(Stellaria media)

Also known as: Chicken’s Meat, Chickenweed, Stitchwort

Birds and chickens love to peck at the flowers and seeds of this widespread and abundant sprawling annual, which persists throughout winter in mild climates. It spreads and forms masses of leaves on weak stems that creep over the soil, forming clumps up to 14" (35cm) but usually less.

The plant produces white, star-like flowers about ⅜" (9mm) across throughout the year, but mainly in summer. It is widely spread throughout the world and found in most countries, but is most abundant in Asia, Europe, north Africa, and throughout North America.

You’ll find it: On bare ground, especially in light, cultivated soil where seeds quickly germinate and create carpets of leaves, stems, and flowers.

Leaves: The abundant soft, bright green, oval leaves clasp stems; as they age, they become darker and tougher.

Harvesting the leaves: If tugged sharply, whole stems complete with soil-covered roots are pulled up, so use sharp scissors to cut off only the young, leaf-clad stems. If they appear dirty, wash and allow to dry.

Using the leaves: Young leaves have a mild flavor and can be eaten raw in salads, when they are at their best. Young stems are just as tender as the leaves and can also be eaten, although some people remove them. Add the leaves to scrambled eggs, use in soups, or gently soften in butter, which makes their flavor resemble spring spinach.

In times of scarcity, Chickweed seeds have been ground to a fine powder and used to make bread or to thicken soups; the leaves were picked, dried, and infused in boiling water to make a tea.

Chicory

(Cichorium intybus)

Also known as: Barbe-de-Capuchin, Blue Daisy, Blue Endive, Blue-sailors, Bunk, Coffee Weed, Common Chicory, Succory, Wild Succory, Witloof

A well-known perennial with a long taproot and stiffly erect, grooved stems to 36" (90cm), chicory is native to many regions—much of Europe, western Asia, and North Africa. It now thrives in eastern Asia, North and South America, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. The roots are eaten as a vegetable, the leaves used in salads, and flowers as a garnish. The roots are also used as a coffee substitute.

You’ll find it: In grassy areas and on waste ground, especially on chalk, alongside old vegetable gardens, community gardens, and near derelict country cottages.

Roots, leaves, and flower heads: The light-brown roots are 18" (45cm) or more long when in light, deeply cultivated soil, and somewhat shorter when growing in heavy soil. Basal leaves above the root’s top are spear-shaped and stemless while upper ones clasp upright, stiff stems. Stems bear azure-blue daisy-like flowers from early summer to early autumn.

Harvesting the roots and leaves: Roots are best dug up in late autumn, when the leaves are dying down. However, unless you have permission from the landowner, it is illegal to dig up plants growing in the wild. Pick young, fresh leaves for salads, washing and drying before using. Flowers, for garnish, should be picked when young and fresh.

Using the roots and leaves: Apart from a coffee substitute, roots can be grated and added to salads, or eaten as a cooked vegetable; reduce their bitterness by boiling for the second time in fresh water. Some people, however, prefer the bitter taste.

Using the leaves: Add to summer salads.

Chicory Coffee

To use as a coffee substitute, clean, peel, and chop up the roots into 3" (7.5cm) long pieces, then roast under a grill until deep brown, firm, and crisp. When completely cool, grind the crisp roots in a coffee grinder or food processor to form coffee-like granules or powder.

Chicory is highly prized in some countries as it produces a coffee with a deep color and does not contain caffeine. Occasionally, it is blended with “true” coffee.

Comfrey

(Symphytum officinale)

Also known as: Back-wort, Boneset, Bruisewort, Church Bells, Common Comfrey, Healing Herb, Knitbone, Pigweed

Growing 48" (1.2m) high, comfrey is a bushy herbaceous perennial famed for its ability to grow in low temperatures and its prodigious yield of leaves, which are used to feed cattle. Its cream-white, mauve, yellow-white, or pink bell-shaped flowers are borne in clusters during late spring and early summer. Native to much of Europe and Asia, it has been taken to other countries as animal fodder and has escaped into the wild and become naturalized. It now thrives in North and South America and New Zealand. In addition to its fodder qualities, comfrey is widely recommended in country cures, including reducing pain, healing broken bones, as a poultice, and to relieve coughs.

You’ll find it: Especially in damp areas alongside wet ditches, streams, and rivers; also, at the edges of fields where it was once cultivated.

Leaves: Masses of broad, spear-shaped, hairy-surfaced, mid-green leaves up to 10" (25cm) long.

Harvesting the leaves: Cut young leaves from plants and wash before use.

Using the leaves: When dipped in batter and fried, comfrey is claimed to be one of the tastiest delights for foragers. The stems and leaves can be boiled in the same way as cabbage. The older leaves have as much flavor as younger ones in cooked dishes, but the young leaves are picked in spring to add to salads.

Comfrey Soup

INGREDIENTS

• 1¾ tablespoons (25g) margarine or butter

• 3 tablespoons (25g) plain flour

• 2½ cups (600ml) milk

• 3–4 tablespoons comfrey leaves, finely chopped

• Stock cube (chicken or vegetable)

• 1¼ cups (300ml) water

INSTRUCTIONS

1. Make a white sauce as a base using margarine or butter, plain flour, and milk.

2. Add comfrey leaves, which have first been lightly cooked in butter as you would spinach.

3. Add a crumbled stock cube and water to the soup, then add seasonings to taste.

4. Bring the soup to a gentle boil and stir for a few minutes before serving with crusty bread or croutons.

Curled Dock

(Rumex crispus)

Also known as: Curly Dock, Narrow-leaf Dock, Sour Dock, Yellow Dock

An upright herbaceous perennial that grows to about 42" (1m) with stems of densely clustered tiny flowers from early summer to mid-autumn that turn a rich brown after they start to produce seeds. The shiny brown seeds have a covering that allows them to float on water as well as to be caught in wool and animal fur, enabling plants to spread easily and rapidly. Indeed, in some areas, this plant is treated as a pest as it invades cultivated crops.

It is seen all over Africa, Europe, and Asia, but has been naturalized in the United States and some parts of Canada.

You’ll find it: In a wide range of habitats, including shingle beaches, sand dunes, on waste ground, cultivated soil, and in grassy areas.

Leaves: Dark green, lance-shaped, and wavy edged. Unlike some docks, the lower leaves are not distinctively heart-shaped at their bases.

Harvesting the leaves: Preferably cut at the base when the leaves are young, and use immediately before they wilt and become limp.

Using the leaves: Add fresh young leaves to salads—wash and dry first to ensure they are not contaminated by animals. Old leaves are usually too bitter to be eaten fresh but can be boiled in several changes of water to make them palatable; use these as a green vegetable.

Young leaves are often cooked like spinach to accompany ham or bacon; either blanch the leaves quickly in a little water or sauté with a tablespoon of butter, add a tiny amount of vinegar, and season with salt and pepper.

Edible Docks

Several related species are ideal for foraging, including Sorrel (see here). Other docks include Rumex obtusifolius, the Broad-Leaved Dock, with leaves that can be eaten when young but are usually more bitter than curled dock. It is also known as Butter Dock because its long, broad leaves were used to wrap around butter to keep it cool and fresh.

Monk’s Rhubarb (Rumex alpinus, earlier known as Rumex pseudoalpinus) is native to central and southern Europe and parts of Asia. In the Middle Ages, it was used as a potherb, when young leaves were eaten fresh. It is now naturalized in many countries, including North America.

Dandelion

(Taraxacum officinale)

Also known as: Clock Flower, Clocks and Watches, Common Dandelion