Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Creative Homeowner

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Specialist Guide

- Sprache: Englisch

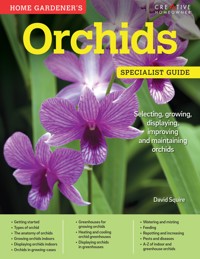

Home Gardener's Orchids is the essential guide to choosing and growing orchids successfully in any climate. Orchids have a reputation for being hard to grow, but this comprehensive manual will lead gardeners straight to the best variety to cultivate in their climate, and provide all the necessary information to make their flowers flourish. Dozens of dazzling photographs showcase many of these exotic blooms, while detailed sections discuss how to raise them indoors and in growing cases, as well as in greenhouses, and give plenty of advice on watering, misting, composts, heating and cooling, repotting, and dealing with pests and diseases. This remarkable illustrated A-to-Z features important tips for every orchid, and includes notes on whether it's easy to grow and where to grow it, what temperature it needs, and much more.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 171

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Author’s foreword

GETTING STARTED

What are orchids?

What are terrestrial orchids?

What are epiphytic orchids?

Orchidomania

Orchid flowers

The anatomy of orchids

GROWING ORCHIDS INDOORS

Indoor orchids

Displaying orchids indoors

Orchids in growing-cases

How to grow indoor orchids

Cymbidiums

Miltonias

Odontoglossums

Paphiopedilums

Phalaenopsis

Zygopetalums

Growing other indoor orchids

GROWING ORCHIDS IN GREENHOUSES

Guide to greenhouse orchids

Greenhouses for growing orchids

Heating and cooling greenhouses

Displaying orchids in greenhouses

Watering, misting, composts and feeding

Repotting an orchid

Increasing orchids

Pests of orchids

Diseases of orchids

A–Z OF ORCHIDS

Orchids for growing indoors and in greenhouses

Glossary

Index

North American EditionCopyright © 2005, 2016 text AG&G BooksCopyright © 2005, 2016 illustrations and photographs IMM Lifestyle BooksCopyright © 2005, 2016 IMM Lifestyle Books

This book may not be reproduced, either in part or in its entirety, in any form, by any means, without written permission from the publisher, with the exception of brief excerpts for purposes of radio, television, or published review. All rights, including the right of translation, are reserved. Note: Be sure to familiarize yourself with manufacturer’s instructions for tools, equipment, and materials before beginning a project. Although all possible measures have been taken to ensure the accuracy of the material presented, neither the author nor the publisher is liable in case of misinterpretation of directions, misapplication, or typographical error.

Creative Homeowner® is a registered trademark of New Design Originals Corporation.Designed and created for IMM Lifestyle Books by AG&G Books. Copyright © 2003 “Specialist” AG&G BooksDesign: Glyn Bridgewater; Illustrations: Dawn Brend, Gill Bridgewater, Coral Mula, and Ann Winterbotham; Editor: Alison Copland; Photographs: see page 80

Current Printing (last digit)10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1Printed in Singapore

XXXXXXXXXX is published by Creative Homeowner under license with IMM Lifestyle Books.

eISBN: 978-1-60765-213-7

Creative Homeowner®, www.creativehomeowner.com, is distributed exclusively in North America by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc., 800-457-9112, 1970 Broad Street, East Petersburg, PA 17520.

Author’s foreword

Orchids are often thought to be difficult to grow and almost impossible for indoor cultivation. In earlier years this was probably accurate, but nowadays it is possible for anyone to grow orchids indoors. However, the major part of such success is in choosing suitable plants. Increasingly, garden centres as well as specialist nurseries sell orchids that are suitable for growing indoors, perhaps on windowsills, tables and in display cabinets. Before creating your own indoor collection, however, it is well worth visiting a few nurseries to see the range of orchids they offer and to make a note of the ones that especially appeal to you.

Orchids can also be grown in greenhouses and heated conservatories, and for this purpose there is an even wider range of suitable plants. Wherever you grow them, their delicate, intricate, colourful and often wax-like nature will enthral you. The orchid family is one of the largest in the plant kingdom, including nearly 800 different genera, more than 25,000 species and in excess of 100,000 man-made hybrids, with many further ones being introduced each year. There are orchids to please just about everyone’s taste.

This thoroughly practical, all-colour book guides readers through the plant selection process and the special growing techniques required by orchids, as well as providing an insight into the vast range of orchids that are currently available for growing both indoors and in greenhouses or conservatories.

About the Authors

David Squire has a lifetime’s experience with plants, both cultivated and native types. Throughout his gardening and journalistic careers, David has written more than 80 books on plants and gardening, including 14 books in this Specialist Guide series. He also has a wide interest in the uses of native plants, whether for eating and survival, or for their historical roles in medicine, folklore and customs.

SPECIALIST NURSERIES

Orchid nurseries often specialize in certain types of orchids. Some concentrate on species orchids, and others on hybrids of selected genera.

A glance through a nursery catalogue – or, perhaps, a scroll through relevant websites on the internet – will soon give you an idea of their speciality and range of plants. Do not be deterred from buying from overseas nurseries – many have excellent distribution arrangements as well as agents acting for them in various countries.

From botanical specimens to decorative features

In earlier years, orchids were considered to be colourful, exciting and, perhaps, novel plants that mainly interested botanists. Nowadays, this has radically changed, and suitable ones compete with houseplants as room decorations.

A range of ways to display orchids, either singly or in groups, is described and illustrated on page 15. Many can be grown on windowsills, and suitable types are indicated on page 14. Orchids are even candidates for growing in cabinets and in places where supplementary light has to be provided (see pages 18–19).

What are orchids?

There are two basic types of orchid. Terrestrial orchids grow at ground level and are rooted in soil. The other type is epiphytic and these grow on trees and shrubs. A few epiphytic orchids grow on debris on rocks, and these are called lithophytes. Epiphytic orchids are not parasitical and use their host solely for support and anchorage. They grow in dead plant debris which collects in the angles of branches and provides moisture and nourishment.

Are there many types of orchid?

THE ORCHID FAMILY

Orchids are perennial plants and live from one year to another. Some are herbaceous (their foliage dies down in winter), while others are evergreen. Epiphytic orchids have showier and more flamboyant flowers than terrestrial types, and invariably these are the ones that are primarily grown indoors, as well as in greenhouses and conservatories. The flowers of terrestrial types are less dramatic but nevertheless equally captivating.

The range of orchids is wide but usually restricted to those that can be relatively easily grown. These include Cattleyas, Coelogynes, Cymbidiums, Dendrobiums, Laelias, Lycastes, Miltonias, Odontoglossums, Oncidiums, Paphiopedilums, Phalaenopsis, Pleiones, Stanhopeas, Vandas, Vuylstekearas and Zygopetalums. Members of these families – as well as others – are described and featured on pages 46–77.

Dendrobium draconsis belongs to a large and varied genus of orchids. A number of the species are cultivated, as well as a wide range of colourful and distinctive hybrids.

Thunia Gattonense, a well-established epiphytic orchid, has beautiful foliage as well as large and distinctive flowers in summer.

Specialist orchid nurseries, as well as botanical gardens, create orchid gardens where spectacular displays can be produced. Other humid-loving plants can be grown with them.

Where do orchids come from?

The orchid family is one of the largest in the plant kingdom. Orchids which grow in soil at ground level are usually found in temperate climates, whereas those that grow in crevices and junctions of branches are mainly native to tropical or subtropical regions. The latter invariably enjoy a damp atmosphere, which helps to keep their exposed roots moist, active and pliable.

What are terrestrial orchids?

Terrestrial orchids are mainly herbaceous perennials that grow in soil at ground level and have either underground tubers or a tuft of fleshy roots at their base. The leaves are strap-shaped; they range in colour from pale to dark green, and are sometimes spotted or mottled. Several terrestrial orchids are cultivated, but they are usually more difficult to grow than epiphytic types, which have a tropical or subtropical heritage.

How can I recognize terrestrial orchids?

WHICH TERRESTRIAL ORCHIDS CAN I GROW?

Most orchids that are grown in greenhouses and conservatories are epiphytes, but there are a few superb terrestrial types to consider. These include the following.

• Cypripedium orchids were, in earlier years, recommended for growing in gardens, in rock gardens and beneath deciduous trees. Unfortunately, they are difficult to establish outdoors in cool climates.

• Paphiopedilum orchids are mostly terrestrial. They have been widely hybridized and many superb hybrids are now available; most are ideal for growing indoors. Flowers are readily identified by the pouched features at their fronts. Flower colours include yellow, green, brown, violet, purple and deep crimson.

• Pleione orchids are terrestrial or semi-epiphytic and in the wild grow on tree trunks and branches, as well as on mossy rocks. In cultivation, some species are grown in cold greenhouses or indoors. Alternatively, in mild areas the hardier types such as Pleione formosana can be grown successfully in rock gardens.

Do terrestrial orchids survive lower temperatures than epiphytes?

Because terrestrial orchids are mainly native to temperate regions of the world, they are hardier than the epiphytic types. Some terrestrial orchids can therefore be grown either in cold greenhouses or outdoors in gardens where the temperature does not fall too low in winter.

Paphiopedilum flowers have distinctive pouches at the front, and belong to a genus that has been enthusiastically hybridized.

The tiered flowers on the stem in the left picture contrast with the flower of Paphiopedilum primulinum.

Witch factor

It is said that witches used the tubers of terrestrial orchids in their potions and drugs, many of which were planned to influence love. Fresh tubers were said to promote true love, while withered ones were thought to check wrong and ill-advised passions.

Nicholas Culpeper, the English seventeenth-century physician and herbalist, wrote about orchids being under the dominion of Venus.

In addition, bruised orchid tubers were used medicinally in the treatment of certain infections.

CONSERVING NATIVE ORCHIDS

During earlier years, many terrestrial orchids were dug up from their native soil in the wishful belief that they could be transplanted into a garden. Invariably, this resulted in the destruction of many plants. Additionally, many were dug up and pressed as part of a native plant collection.

Several centuries ago, the tuberous and finger-like roots of Orchis mascula (Early Purple Orchid) were used to make salop, a drink popular before the introduction of coffee. This resulted in the destruction of many of these orchids, a distinctive plant also known as Dead Men’s Fingers and King’s Fingers.

Today, it is better to photograph or sketch plants rather than to dig them up, and always take care not to trample on them.

DO TERRESTRIAL ORCHIDS HAVE FRAGRANT FLOWERS?

A few terrestrial orchids have scented flowers; in some, the scent is pleasant, but often it is offensive. Here are some examples.

• Herminium monorchis (Musk Orchid) develops small greenish-yellow flowers, and these emit a soft, honey-like fragrance that attracts small bees and beetles.

• Himantoglossum hircinum (Lizard Orchid) has flowers that resemble a lizard and emit the rancid smell of stale perspiration akin to goats.

• Leucorchis albida or Pseudorchis albida (Small White Orchid) has an attractive fragrance, with strongly vanilla-like scent.

• Orchis mascula (Early Purple Orchid) has bright purple flowers that when newly opened give off a vanilla scent, but after fertilization this changes to a goat- or cat-like redolence.

• Orchis ustulata (Dark-winged Orchid) has flowers with a sweet, almond-like fragrance.

Spiranthes autumnalis (Autumn Lady’s Tresses) emits an almond-like scent.

WHAT ARE HYBRID ORCHIDS?

Hybrid orchids are man-made plants that have been raised from the crossing of one or more parents. For example, plants in the genus xVuylstekeara are derived from Cochlioda, Miltonia and Odontoglossum. Others, such as xLaeliocattleya, are derived from just two genera – Laelia and Cattleya. Hybrid plants are indicated by a small cross being placed in front of the first name, such as xWilsonara.

Nowadays, most new orchids result from crosses – and back-crosses – with orchids originally introduced from their native countries many decades ago. Refined hybridizing developments have encouraged the creation of new hybrids, and this has been stimulated by greater interest in orchids.

DO ALL ORCHIDS HAVE COMMON NAMES?

Many orchids, including Cattleyas with their distinctive and colourful nature, are ideal for creating corsages.

Epiphytic orchids

Only a few epiphytic orchids have common names, although Cattleyas are often known as Corsage Orchids because of their use in the florist trade (see pages 16–17).

Odontoglossum grande has been dubbed the Tiger Orchid, reflecting the bright yellow petals which are barred chestnut-brown. Odontoglossum crispum has been known as the Queen of Orchids on account of its magnificent, sparkling white or pale rose flowers, which are spotted or blotched purple or red. So attractive are the flowers of this plant that the species was nearly brought to extinction in the wild.

Terrestrial orchids

Terrestrial orchids are blessed with many highly descriptive local names which invariably refer to the shapes and colours of their flowers. Several members of the Spiranthes genus have ‘Lady’s Tresses’ in their names, while the common names of others indicate the type of soil and area in which they grow. These include the Fen Orchid and Meadow Orchid. Gymnadenia conopsea is known as the Fragrant Orchid, on account of its flowers being highly scented.

Pleiones are terrestrial or semi-epiphytic orchids; Pleione formosana is very popular, with many varieties available.

Odontoglossum grande is called the Tiger Orchid because of its striped flowers.

Hardy orchid

Pleione formosana, which is native to a wide area from Tibet to Taiwan (previously called Formosa), is ideal for growing in a cool living room because of its hardiness. Alpine plant enthusiasts have long grown this orchid in alpine greenhouses.

What are epiphytic orchids?

Epiphytic orchids naturally grow above ground, in crevices and junctions of branches where they gain moisture and food from decaying plant debris which collects in them. They are mainly native to tropical and subtropical regions. These orchids are not parasites, but for their convenience dwell above the ground, with specially adapted roots that serve both to hold them in place and to absorb the moisture and nutrients necessary for survival.

Do epiphytic orchids grow above the ground?

WIDE RANGE OF EPIPHYTIC ORCHIDS

There are many epiphytic orchids but only a relatively few are grown as a hobby in greenhouses or conservatories, and even fewer indoors. Here are a few superb orchids to consider. Together with other orchids, they are described in greater detail in the A–Z of orchids on pages 46–77. Their range of shapes and colours will amaze you.

x Brassolaeliocattleya

Hybrids between Brassovola, Laelia and Cattleya, with flowers up to 15 cm (6 in) wide. They can be grown indoors or in greenhouses (see page 48).

Cattleya

Popular orchids, native to a wide area from Mexico to southern Brazil. They are widely grown in greenhouses, as well as indoors (see page 49).

Cirrhopetalum

Evergreen orchids from Africa, Asia and the Pacific Islands. Flowering from mid- spring to early summer, they are best grown in a greenhouse (see page 53).

Coelogyne

Distinctive evergreen orchids from the tropics that often have fragrant flowers and are usually grown in greenhouses (see page 53).

Cymbidium

Easy to grow – some terrestrial and others epiphytic. They are ideal for gardeners new to orchids. Grow in greenhouses or indoors (see page 54).

Dendrobium

Most are deciduous, but those from warm areas are evergreen. Many are easily grown in greenhouses as well as indoors (see page 58).

Epidendrum

A group of New World orchids, mainly deciduous and from Florida to Brazil. Most are easy to grow and ideal for growing in greenhouses (see page 61).

Laelia

New World evergreen orchids native to an area from Mexico to Brazil. They are ideal for growing in greenhouses, as well as indoors (see page 62).

x Laeliocattleya

A group of hybrid orchids, between Laelia and Cattleya. They mainly resemble Cattleyas and are usually grown in greenhouses (see page 62).

Lycaste

Group of tropical, deciduous orchids from Central America. They are ideal for growing in greenhouses as well as indoors (see page 63).

Masdevallia

Group of evergreen orchids native to forest areas in the Andes, often known as Kite Orchids because of the long tails to the flowers. They are usually grown in a greenhouse (see page 63).

Maxillaria

A group of terrestrial and epiphytic evergreen orchids, native to an area from Florida through Central America to Argentina (see page 63).

Miltonia

Distinctive, evergreen orchids from tropical America, some with pansy-like flowers. They are ideal for growing in greenhouses or indoors (see page 64).

Odontoglossum

Popular evergreen orchids, native to Central America and tropical South America, grown in greenhouses as well as indoors (see page 67).

Oncidium

Large group of evergreen orchids, native to the American subtropics. They are ideal for growing in greenhouses as well as indoors (see page 68).

Phalaenopsis

Evergreen orchids, native to a wide area from India and Indonesia to the Philippines and northern Australia. They are often grown in greenhouses as well as indoors (see page 70).

x Sophrolaeliocattleya

Group of hybrid orchids that are derived from Cattleya, Laelia and Sophronitis, which mainly resemble Cattleyas (see page 74).

Stanhopea

Evergreen orchids native to Central America, the American tropics and Mexico, usually grown in greenhouses as well as indoors (see page 74).

Vanda

Popular group of evergreen orchids native to tropical Asia. They are grown in greenhouses as well as indoors (see page 75).

x Vuylstekeara

Group of hybrid orchids, derived from Cochlioda, Miltonia and Odontoglossum. They mainly bear a resemblance to Odontoglossums. They are grown in greenhouses or indoors (see page 76).

Zygopetalum

Evergreen orchids from Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia and the Guianas. They can be grown in greenhouses as well as indoors (see page 77).

Orchidomania

Records indicate that the Greek thinker and writer Theophrastus, born about 370 bc and a friend of Aristotle and Plato, referred to a group of plants known as ‘orchis’ on account of the large, rounded, testicular tubers borne in pairs at the bases of many terrestrial orchids (the Greek for testis is orchis). During the early 1700s, the church, trading companies and botanists ventured into foreign countries, returning with plants, some of them orchids.

When did orchids become popular?

CHANCE PLAYS A ROLE

By 1789, there were about 15 exotic orchid species growing in Britain and Cattleyas were being regularly flowered during the second decade of the 1800s. However, by chance and at about the same time, a consignment of tropical plants wrapped in other tough plants was sent to the North London gardener William Cattley, who was a tropical plant enthusiast (his name is now remembered in the genus Cattleya).

Many orchids were bred by the Veitch Nursery, producing the first man-made orchid hybrid in 1856. This illustration shows a two-year old orchid seedling.

Cattley was intrigued by the wrapping material and by late 1818 he had encouraged it to bear flowers that caused a sensation in the plant world. Nothing like it had been known in cultivation, and before long a mania for orchids had begun in Britain, Europe and North America, but at a dreadful cost for orchids in the wild where whole areas were cleared of orchids. Trees were felled in order to get at orchids growing at their tops, and land was denuded of plants to prevent competitors laying hands on them. It was of no credit to horticulture and reveals how depraved people are when money is the dictum. Nevertheless, new species of orchid flooded into Europe.

Many new plant nurseries came into business, some sending out collectors to tropical and subtropical regions. Towards the end of the 1890s, the cost of maintaining a collector abroad was about £3,000 a year, and some firms had upwards of 20 collectors. This cost was reflected in the expense of growing orchids, which mainly became a pursuit of the wealthy.

This delicate illustration of Cypripedium parviflorum (Yellow Ladies Slipper) was drawn by S. Edwards in 1820. It flowers from mid-spring to mid-summer and is now better known as Cypripedium calceolus var. parviflorum. In North America it is called Small Golden Slipper.

THE INTRODUCTION OF HYBRIDS

The large, frilly, pink petals of this Odontoglossum hybrid create a dramatic feature.

The technique of creating hybrids was discovered about the mid-1800s and the first man-made hybrids were crosses between Calanthe furcata and Calanthe masuca, with flowering in 1856. However, it is known that natural hybrids had occurred earlier. Nowadays, many hybrids are the result of crosses between two or three different genera – sometimes more – and these are acknowledged by putting an x before the name. A look through an orchid catalogue soon reveals the wealth of hybrids.

x Beallara