9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

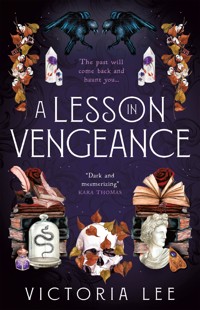

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A twisty dark academia thriller about a centuries-old, ivy-covered boarding school haunted by its history of witchcraft and two girls dangerously close to digging up the past. Perfect for fans of V.E. Schwab, Leigh Bardugo, M.L. Rio and Donna Tartt. Felicity Morrow is back at the Dalloway School to finish her senior year after the tragic death of her girlfriend. She even has her old room in Godwin House, the exclusive dormitory rumored to be haunted by the spirits of five Dalloway students―girls some say were witches. Witchcraft is woven into Dalloway's past. The school doesn't talk about it, but the students do. In secret rooms and shadowy corners, girls convene. And before her girlfriend died, Felicity was drawn to the dark. She's determined to leave that behind now, but it's hard when Dalloway's occult history is everywhere. And when the new girl won't let her forget. It's Ellis Haley's first year at Dalloway. A prodigy novelist at seventeen, Ellis is eccentric and brilliant, and Felicity can't shake the pull she feels to her. So when Ellis asks Felicity for help researching the Dalloway Five for her second book, Felicity can't say no. And when history begins to repeat itself, Felicity will have to face the darkness in Dalloway―and in herself.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 465

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Part 1

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part 2

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Part 3

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Part 4

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Part 5

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Part 6

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Part 7

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Three years later

Acknowledgments

About the Author

“A Lesson in Vengeance is at once dark and mesmerizing, with spine-tingling suspense and mind-bending twists. I loved it.”

Kara Thomas, author of The Cheerleaders and That Weekend

“A smart, layered, thought-provoking thriller about female desire and the intimacy of violence.”

Ava Reid, author of The Wolf and the Woodsman

“Darkly radiant and brilliantly wicked, A Lesson in Vengeance is a sharp dissection of queerness, ambition, and the forbidden luster of the occult. This book will possess you from first pages to its haunting, final words.”

Ryan La Sala, author of Be Dazzled and Reverie

“A Lesson in Vengeance is the witchy boarding school story I always knew I wanted, a gorgeous take on the complicated bonds of female love and friendship, told in lyrical, creeping prose as haunting as the tale itself. The ghosts of Felicity, Ellis, and Alex—and of Dalloway School and its historical witches—will linger with you long after the final page.”

Lana Popović, author of Wicked Like a Wildfire

“With queer primary characters, an irresistible gothic atmosphere, and unrelenting creeping dread, this propulsive work of dark academia is both thrilling and thought-provoking.”

Publishers Weekly, starred review

“A layered, stylized, brooding mystery that will draw readers in.”

Kirkus

“[A] twisty, immersive thriller.”

Booklist, starred review

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

A Lesson in Vengeance

Print edition ISBN: 9781789099768

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789099775

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: February 2022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Victoria Lee, 2022

Victoria Lee asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For coffee-stained girls in libraries

Thirteen thousand feet above sea level, you can drown in air like water.

I read that drowning is a good way to go. By all accounts the pain fades and euphoria blooms in its place like hothouse flowers, red orchid roots tethered to the stones in your pocket.

Falling would be worse.

Falling is barbed-wire terror ripping down your spine, a sharp drop and a sudden stop, scrabbling for a rope that isn’t there.

My cheek is pressed against the snow. I don’t feel cold anymore. I am part of the mountain, its frigid stone heart beating alongside mine. The storm batters against my back, tries to peel me off this rock like lichen. But I am not lichen. I am limestone and schist, veined with quartz. I am immovable.

And up this high, pinned against the eastern face with thin air crystallizing in my lungs, I am the only thing left alive.

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality.

—Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House

The legacy of Dalloway School is not its alumnae, although those include a variety of luminaries such as award-winning playwrights and future senators. The legacy of Dalloway is the bones it was built on.

—Gertrude Milliner, “The Feminization of Witchcraft in Post-Revolutionary America,” Journal of Cultural History

Dalloway School rises from the Catskill foothills like a crown upon an auburn head. Accessible only by gravel road and flanked by a mirror-glass lake to the east, its brick-faced buildings stand with their backs turned to the gate and their windows shuttered. My mother is silent in the front seat; we haven’t spoken since New Paltz, when she remarked on how flat the land could be so close to the mountains.

That was an hour ago. I should be glad, I suppose, that she came at all. But, to be honest, I prefer the mutual indifference that endured between me and the hired driver who met me at the airport every year before this one. The driver had her own problems, ones that didn’t involve me.

The same cannot be said for my mother.

We park in front of Sybil Hall and hand the keys to a valet, who will take care of the luggage. This is the downside to arriving at school four days early: we have to meet the dean of students in her office and then tramp across campus together, my mother and the dean chatting six steps ahead and me trailing behind. The lake glitters like a silver coin, visible in the gap between hills. I keep my gaze fixed on the dean’s wrist, on the bronze key that dangles from a string around that wrist: the key to Godwin House.

Godwin House is isolated from the rest of campus by a copse of balsam firs, up a sharply pitched road and perched atop a small ridge—unevenly, as the house was built three hundred years ago on the remains of an ancient avalanche. And as the ground settled, the house did too: crookedly. Inside, the floors slope noticeably along an east-west axis, cracks gaping beneath doors and the kitchen table wobbling under weight. Since I arrived at Dalloway five years ago, there have been two attempts to have the building condemned, or at the very least renovated down to the bones—but we, the inhabitants, protested vociferously enough that the school abandoned its plans both times. And why shouldn’t we protest? Godwin House belongs to us, to the literary effete of Dalloway, self-presumed natural heirs to Emily Dickinson—who had stayed here once while visiting a friend in Woodstock—and we like our house as is. Including its gnarled skeleton.

“You can take your meals at the faculty dining hall for now,” Dean Marriott informs me once she has deposited me in my room. It’s the same room I always stayed in, before. The same water stain on the ceiling, the same yellowing curtains drifting in the breeze from the open window.

I wonder if they kept it empty for me, or if my mother browbeat the school into kicking some other girl out when I rematriculated.

“Miss MacDonald should be back by now,” the dean goes on. “She’s the housemistress for Godwin again this year. You can go by her office sometime this afternoon, let her know you’ve arrived.”

The dean gives me her personal number, too. A liability thing, most likely: After all, what if I have a breakdown on campus? What if, beneath the tailored skirt and tennis sweater, I’m one lonely night away from stripping off my clothes and hurtling naked through the woods like some delirious maenad?

Better to play it safe.

I take the number and slip it into my skirt pocket. I clench it in my fist until the paper’s an inky nugget against my palm.

Once the dean is gone, my mother turns to look at the room properly, her cool gaze taking in the shabby rug and the mahogany dresser with its chipped corners. I imagine she wonders what becomes of the sixty thousand she pays in tuition each year.

“Perhaps,” she says after a long moment, “I should stay the night in town, let you settle in. . . .”

It’s not a real offer, and when I shake my head she looks relieved. She can fly back to Aspen this afternoon and be drinking cabernet in her study by nightfall.

“All right, then. All right. Well.” She considers me, her shell-pink fingernails pressing in against opposite arms. “You have the dean’s number.”

“Yes.”

“Right. Yes. Hopefully you won’t need it.”

She embraces me, my face buried against the crook of her neck, where everything smells like Acqua di Parma and airplane sweat.

I watch her retreat down the path until she vanishes around the curve, past the balsams—just to make sure she’s really gone. Then I drag my suitcases up onto the bed and start unpacking.

I hang my dresses in the closet, arranged by color and fabric—gauzy white cotton, cool-water cream silk—and pretend not to remember the spot where I’d pried the baseboard loose from the wall last year and concealed my version of contraband: tarot cards, long taper candles, herbs hidden in empty mint tins. I used to arrange them atop my dresser in a neat row the way another girl might arrange her makeup.

This time I stack my dresser with jewelry instead. When I look up I catch my own gaze in the mirror: blond hair tied back with a ribbon, politely neutral lipstick smudging my lips.

I scrub it off against my wrist. After all, there’s no one around to impress.

Even with nothing to distract me from the task, unpacking still takes the better part of three hours. And when I’ve kicked the empty suitcases under my bed and turned to survey the final product, I realize I hadn’t thought past this point. It’s still early afternoon, the distant lake now glittering golden outside my window, and I don’t know what to do next.

By the middle of my first attempt at a senior year, I’d accrued such a collection of books in my Godwin room that they were spilling off my shelves, the overflow stacked up on my floor and the corner of my dresser, littering the foot of my bed to get shoved out of the way in my sleep. They all had to be moved out when I didn’t come back for spring semester last year. The few books I was able to fit in my suitcases this year are a poor replacement: a single shelf not even completely filled, the last two books tipped forlornly against the wood siding.

I decide to go down to the common room. It’s a better reading atmosphere anyway; me and Alex used to sprawl out on the Persian carpet amid a fortress of books—teacups at our elbows and jazz playing off Alex’s Bluetooth speaker.

Alex.

The memory lances through me like a thrown dart. It’s unexpected enough to steal my breath away, and for a moment I’m standing there dizzy in my own doorway as the house tilts and spins.

I’d known it would be worse, coming back here. Dr. Ortega had explained it to me before I left, her voice placid and reassuring: how grief would tie itself to the small things, that I’d be living my life as normal and then a bit of music or the cut of a girl’s smile would remind me of her and it would all flood back in.

I understand the concept of sense memory. But understanding isn’t preparation.

All at once I want nothing more than to dart out of Godwin House and run down the hill, onto the quad, where the white sunshine will blot out any ghosts.

Except that’s weakness, and I refuse to be weak.

This is why I’m here, I tell myself. I came early so I’d have time to adjust. Well, then. Let’s adjust.

I suck in a lungful of air and make myself go into the hall, down two flights of stairs to the ground floor. I find some tea in the house kitchen cabinet—probably left over from last year—boil some water, and carry the mug with me into the common room while it brews.

The common room is the largest space in the house. It claims the entire western wall, its massive windows gazing out toward the woods, and is therefore dark even at midafternoon. Shadows hang like drapes from the ceiling, until I flick on a few of the lamps and amber light brightens the deep corners.

No ghosts here.

Godwin House was built in the early eighteenth century, the first construction of Dalloway School. Within ten years of its founding, it saw five violent deaths. Sometimes I still smell blood on the air, as if Godwin’s macabre history is buried in its uneven foundations alongside Margery Lemont’s bones.

I take the armchair by the window: my favorite, soft and burgundy with a seat cushion that sinks when I sit, as if the chair wants to devour its occupant. I settle in with a Harriet Vane mystery and lock myself in Oxford of the 1930s, in a tangled mess of murderous notes and scholarly dinners and threats exchanged over cakes and cigarettes.

The house feels so different like this. A year ago, midsemester, the halls were raucous with girls’ shouting voices and the clatter of shoes on hardwood, empty teacups scattered across flat surfaces and long hairs clinging to velvet upholstery. All that has been swallowed up by the passage of time. My friends graduated last year. When classes start, Godwin will be home to a brand-new crop of students: third-and fourth-years with bright eyes and souls they sold to literature. Girls who might prefer Oates to Shelley, Alcott to Allende. Girls who know nothing of blood and smoke, the darker kinds of magic.

And I will slide into their group, the last relic of a bygone era, old machinery everyone is anxiously waiting to replace.

My mother wanted me to transfer to Exeter for my final year. Exeter—as if I could survive that any better than being back here. Not that I expected her to understand. But all your friends are gone, she’d said.

I didn’t know how to explain to her that being friendless at Dalloway was better than being friendless anywhere else. At least here the walls know me, the floors, the soil. I am rooted at Dalloway. Dalloway is mine.

Thump.

The sound startles me enough that I drop my book, gaze flicking toward the ceiling. I taste iron in my mouth.

It’s nothing. It’s an old house, settling deeper into unsteady land.

I retrieve my book and flip through the pages to find my lost place. I’ve never been afraid of being alone, and I’m not about to start now.

Thump.

This time I’m half expecting it, tension having drawn my spine straight and my free hand into a fist. I put the book aside and slip out of my chair with an unsteady drum beating in my chest. Surely Dean Marriott wouldn’t have let anyone else in the house, right? Unless . . . It’s probably maintenance. They must have someone coming by to clean out the mothballs and change the air filters.

In fact, that makes a lot of sense. The semester will commence at the end of the weekend; now should be peak cleaning time. No doubt I can expect a significant amount of traffic in and out of Godwin, staff scrubbing the floors and throwing open windows.

Only the house was already clean when I arrived.

As I creep up the stairs, I realize the air has gone frigid, a cold that curls in the marrow of my bones. A slow dread rises in my blood. And I know without having to guess where that sound came from.

Alex’s bedroom was the third door down on the right, second floor—directly below my room. I used to stomp on the floor when she played her music too loud. She’d rap back with the handle of a broom.

Four raps: Shut. The. Hell. Up.

This is stupid. This is . . . ridiculous, and irrational, but knowing that does little to quell the seasick feeling beneath my ribs.

I stand in front of the closed door, one hand braced against the wood.

Open it. I should open it.

The wood is cold, cold, cold. A white noise buzzes between my ears, and suddenly I can’t stop envisioning Alex on the other side: decayed and gray, with filmy eyes staring out from a desiccated skull.

Open it.

I can’t open it.

I spin on my heel and dart back down the hall and all the way to the common room. I drag the armchair closer to the tall window and huddle there on its cushion, with Sayers clutched in both hands, staring at the doorway I came through and waiting for a slim figure to drift in from the stairs, dragging dusk like a cloak in her wake.

Nothing comes. Of course it doesn’t. I’m just—

It’s paranoia. It’s the same strain of fear that used to send me lurching awake in the middle of the night with my throat torn raw. It’s guilt reaching long fingers into the soft underbelly of my mind and letting the guts spill out.

I don’t know how long it is before I can open my book again and turn my gaze away from the door and to the words instead. No doubt reading murder books alone in an old house is half my problem. Impossible not to startle at every creak and bump when you’re half buried in a story that heavily features library crimes.

The afternoon slips toward evening; I have to turn on more lights and refill my tea in the kitchen, but I finish the book.

I’ve just turned the final page when it happens again:

Thump.

And then, almost immediately after, the slow drag of something heavy across the floor above my head.

This time I don’t hesitate.

I take the stairs up to the second floor two at a time, and I’m halfway down the hall when I realize Alex’s bedroom door is open. Bile surges up my throat, and no . . . no—

But when I come to a stop in front of Alex’s room, there’s no ghost.

A girl sits at Alex’s desk, slim and black-haired with fountain pen in hand. She’s wearing an oversized glen check blazer and silver cuff links. I’ve never seen her before in my life.

She glances up from her writing, and our eyes meet. Hers are gray, the color of the sky at midwinter.

“Who are you?” The words tumble out of me all at once, sharp and aggressive. “What are you doing here?”

The room isn’t empty. The bed has sheets on it. There are houseplants on the windowsill. Books pile atop the dresser.

This girl isn’t Alex, but she’s in Alex’s room. She’s in Alex’s room, and looking at me like I just walked in off the street dripping with garbage.

She sets down her pen and says, “I live here.” Her voice is low, accent like molasses.

For a moment we stare at each other, static humming in my chest. The girl is as calm and motionless as lake water. It’s unnerving. I keep expecting her to ask Why are youhere?—to turn the question back around on me, the intruder—but she never does.

She’s waiting for me to speak. All the niceties are close at hand: introductions, small talk, polite questions about origin and interests. But my jaw is wired shut, and I say nothing.

At last she rises from her seat, chair legs scraping against the hardwood, and shuts the door in my face.

The girl in Alex’s room isn’t a ghost, but she might as well be.

A day passes without us speaking again; the door to Alex’s room remains shut, the only sign of the new occupant’s presence the occasional creak of a floorboard or a dirty coffee cup left out on the kitchen counter. At noon I spot her out on the porch, sitting in a rocking chair with a cigarette in one hand and Oryx and Crake in the other, dressed in a seersucker suit.

I split my time between my bedroom and the common room, venturing once to the faculty dining hall to load up a box of food and abscond with it back to Godwin House; nothing seems worse to me than the prospect of trying to eat while all the English faculty wander up to me to remind me how sorry they are, how difficult it must be, how brave I am to come back here after everything.

If I keep moving—bedroom, common room; common room, bedroom—then maybe the cold won’t catch up to me.

That’s what I tell myself, at least. But in the end I can’t outrun it.

I’m in the reading nook when it happens. I’ve curled up lodged on the window seat at the end of the ground-floor hallway, shoes kicked off and sock feet tucked between the cushions, the books from Dr. Wyatt’s summer reading list stacked on the floor by my hip. My eyelids are heavy, sinking low no matter how hard I fight to keep my gaze fixed on the page. I’ve lit candles even though it’s still late afternoon; the flames flicker and spit, reflecting off the window glass.

A moment, I think. I’ll just close my eyes for a moment.

Sleep swells around me like groundwater. The dark pulls me under.

And then I’m back on the mountain, hands numb in my gloves as I cling to that meager ledge. The storm is unrelenting, sleet battering the nape of my neck. I keep thinking about dark water rising in my lungs. About Alex’s body broken on the rocks.

The snow beneath me isn’t shifting anymore. I perch light on its back, light like an insect, motionless. If I move, the mountain will shiver and swat me away.

If I don’t move, I will die here.

“Then die,” Alex says, and I snap awake.

The hall has gone dark. The tall windows gaze out into the black woods, and the candles have blown out. My breath is the only thing I can hear, heavy and arrhythmic. It bursts out of me in gasps—painful, like I’m at altitude, like I’m still so far above the earth.

I feel her fingers at the back of my neck, nails like shards of ice. I jerk around, but there’s no one there. Shadows stretch out through the empty halls of Godwin House, unseen eyes gazing down from the tall corners. Once upon a time I found it so easy to forget the stories about Godwin House and the five Dalloway witches who lived here three hundred years ago, their blood in our dirt, their bones hanging from our trees. If this place is haunted, it’s haunted by the legacy of murder and magic—not by Alex Haywood.

Alex was the brightest thing in these halls. Alex kept the night at bay.

I need to turn on the lights. But I can’t move from this spot against the window, can’t stop gripping my own knees with both hands.

She isn’t here. She’s gone. She’s gone.

I lurch up and stagger to the nearest floor lamp, yank the chain to switch on the light. The bulb glares white; and I turn to face the hall again, to prove to myself it’s empty. And of course it is. God, what time is it? 3:03 a.m. says my overly bright phone screen. It’s too late for the girl in Alex’s room to still be awake.

I turn on every light between there and my bedroom, pulse stammering as I keep climbing the stairs past the second floor—Don’tlook, don’tlook—and up to the third.

In my room I shut the door and crouch down on the rug. If this were last year I might have cast a spell, a circle of light my protection against the dark. Tonight my hands shake so badly I break three matches before I manage to strike a flame. I don’t make a circle. Magic doesn’t exist. I don’t cast a spell. I just light three candles and hunch forward over their heat.

Practice mindfulness, Dr. Ortega would say. Focus on the flame. Focus on something real.

If anything supernatural wanders these halls, it doesn’t answer; the candle flames flicker in the dim light and cast shifting shadows against the wall.

“No one’s there,” I whisper, and no sooner have the words left my lips than someone knocks.

I startle violently enough that I knock over a candle. The silk rug catches almost instantly, yellow fire eating a quick path across the antique pattern. I’m still stamping out sparks when someone says, “What are you doing?”

I look up. Alex’s replacement stands in my doorway. And although it’s past three in the morning, she’s dressed as if she’s about to walk into a law school interview. She’s even wearing collar studs.

“Summoning the devil. What does it look like?” I answer, but the heat burning in my cheeks betrays me; I’m humiliated. I want to kick the rest of the candles over and burn the whole house down so no one knows I got caught like this.

One of the girl’s brows lifts.

I’ve never been able to do that. Even after ages staring at myself in the mirror, I’ve only ever been able to muster a constipated sort of grimace.

I expect a witty comeback, something sharp and bladed and befitting this strange girl with all her unexpected edges. But she just says, “You left all the lights on.”

“I’ll turn them off.”

“Thank you.” She turns to go, presumably to vanish back downstairs and from my life for another few days.

“Wait,” I say, and she glances back, the candlelight flickering across her face and casting odd shadows beneath her cheekbones. I step gingerly over the remaining flames, but I still feel the heat as my legs cross over. I hold out my hand. “I’m Felicity. Felicity Morrow.”

She eyes my hand for a moment before she finally reaches out and shakes it. Her palm is cool, her grasp strong. “Ellis.”

“Is that a first or a last name?”

She laughs and drops my hand and doesn’t answer. I stand there in the doorway, watching her head back down the hall. Her hips don’t sway when she walks. She just goes, hands in her trouser pockets and the motion of her body straight and sure.

I don’t know why she’s here early. I don’t know why she won’t tell me her name. I don’t know why she never speaks to me, or who she is.

But I want to find a loose thread on the collar of her shirt and tug.

I want to unravel her.

Everyone returns two days later, the Saturday before classes commence. Not in a trickle, but in hordes: the front lot is a hive of cars, the quad flooded with new and returning students and their families—often dragging younger siblings to gaze through the looking glass at their own potential future. Four hundred girls: a small school by most standards, all of us students divvied up into even smaller living communities. Even so, I can’t quite bring myself to go downstairs while the new residents of Godwin House are moving in. But I do leave my door open. From my position on my bed, curled up with a book, I watch the figures crossing back and forth in the third-floor hall.

Godwin House is the smallest on campus—only large enough to fit five students in addition to Housemistress MacDonald, who sleeps on the first floor, and reserved exclusively for upperclassmen. Expanding Godwin to fit more students was another cause we fought against. Just imagine this place with its rickety stairs and slanted floors appended to a modernized glass-and-concrete parasite of an extension, wood and marble giving way to carpet and formica, Godwin no longer the home of Dickinson and witches but a monstrous chimera designed to maximize residential density.

No. We’ve been able to keep Godwin the way it is, the way it was three hundred years ago, when this school was founded. You can still feel history in these halls. At any moment you might turn the corner and find yourself face to face with a ghost from the past.

There are two others assigned to this floor with me: a brown-skinned girl with long black hair, wearing an expression of perpetual boredom, and a pallid, pinch-faced redhead, whom I glimpse from time to time half-hidden behind a worn paperback of The Enchanted April. If they notice me in my room, perched on my bed with my laptop on my knees, they don’t say anything. I watch them direct hired help to carry boxes and suitcases up the stairs, sipping iced coffees while other people sweat for them.

The first time I spot the redhead, a flash of hair vanishing around a corner like sudden flame, I almost think she’s Alex.

She isn’t Alex.

If my mother were here, she would urge me up off this bed and force me into a common space. I’d be shepherded from girl to girl until I’d introduced myself to them all. I’d offer to make tea, a gesture calculated to endear myself to them. I wouldn’t be late for supper, a chance to congregate with the rest of the Godwin girls in the house dining room, to trade summer anecdotes and pass the salt.

I accomplish none of those things, and I do not go to supper at all.

I feel as if the next year has just opened up in front of me, a great and yawning void that consumes all light. What will emerge from that darkness? What ghosts will reach from the shadows to close their fingers around my neck?

A year ago, Alex and I let something evil into this house. What if it never left?

I shut myself in my room and pace from the window to the door and back again, twisting my hands in front of my stomach. Magic isn’t real, I tell myself once again. Ghosts aren’t real.

And if ghosts and magic aren’t real, curses aren’t real, either.

But the tap-tap of the oak tree branches against my window reminds me of bony fingertips on glass, and I can’t get Alex’s voice out of my head.

Tarot isn’t magic, I decide. It’s fortune-telling. It’s a historical practice. It’s . . . it’s essentially a card game. Therefore, there’s no risk courting old habits when I crouch in the closet and peel the baseboard away from the wall, reaching past herbs and candles and old stones to find the familiar metal tin that holds my Smith-Waite deck.

I shove the rest of those dark materials back in place and scuttle out of the closet on my hands, breath coming sharp and shallow.

Magic isn’t real. There’s nothing to be afraid of.

I carry the box to my bed, shuffle the cards, and ask my questions: Will I fit in with these girls? Will I make friends here?

Will Godwin House be anything like what I remember?

I lay out three cards: past, present, future.

Past: the Six of Cups, which represents freedom, happiness. It’s the card of childhood and innocence. Which, I suppose, is why it falls in my past.

Present: the Nine of Wands, reversed. Hesitation. Paranoia. That sounds about right.

And my future: the Devil.

I frown down at my cards, then sweep them back into the deck. I never know what to make of the major arcana. Besides, tarot doesn’t predict the future, or so said Dr. Ortega, anyway. Tarot only means as much as your interpretation tells you about yourself.

There’s no point in agonizing over the cards right now. Instead I check my reflection in the mirror, tying my hair back and applying a fresh coat of lipstick, then go downstairs to meet the rest of them.

I find the new students in the common room. They’re all gathered around the coffee table, seemingly fixated on a chess game being played between Ellis and the redhead. A rose-scented candle burns, classical music playing on vinyl.

Even though I know nothing about chess, I can tell Ellis is winning. The center of the board is controlled by her pawns, the other girl’s pieces pushed off to the flanks and battling to regain lost ground.

“Hi,” I say.

All eyes swing round to fix on me. It’s so abrupt—a single movement, as if synchronized—that I’m left feeling suddenly off balance. My smile is tentative on my mouth.

I’m never tentative. I’m Felicity Morrow.

But these girls don’t know that.

All their gazes turn to Ellis next, as if asking her for permission to speak to me. Ellis sweeps a white pawn off the board and sits back. Drapes a wrist over her knee, says: “That’s Felicity.”

As if I can’t introduce myself. And of course it’s too late now; what am I supposed to say? I can’t just say hi again. I’m certainly not going to agree with her: Yes indeed, my name is Felicity, you are quite correct.

Ellis met these girls a few hours ago, and already she’s established herself as their center of gravity.

One of them—a Black girl with a halo of tight coils, wearing a cardigan I recognize as this season’s Vivienne Westwood—takes pity on me. “Leonie Schuyler.”

It’s enough to prompt the others to speak, at least.

“Kajal Mehta,” says the thin, bored-looking girl from my floor.

“Clara Kennedy.” The red-haired girl, her attention already turned back to the chess game.

And it appears that concludes the conversation. Not that they return to whatever they’d been talking about before; now that I am here, the room has fallen silent, except for the click of Clara’s knight against the board and the sound of a match striking as Ellis lights a cigarette.

Indoors. And not only does no one tell her to put it out, MacDonald fails to preternaturally manifest the way she would had it been me and Alex smoking in the common room: Books are flammable, girls!

Well. I’m hardly going to leave just because they so clearly want me to. In fact . . . I belong here as much as they do. More than they do. I was a resident of Godwin House when they were still first-years begging for directions to the dining hall.

I sit down in an empty armchair and pull out my phone, scrolling through my email while Clara and Kajal exchange incredulous looks—like they’ve never seen someone text before. And maybe they haven’t. They’re all dressed as if they’ve just emerged from the 1960s: tweed skirts and Peter Pan collars and scarlet lipstick.

Ellis finishes the chess game in eight moves—a quick and brutal destruction of Clara’s army—and conversation resumes, albeit stiltedly, as if they’re all trying to forget I’m here. I learn that Leonie spent the summer at her family’s cottage in Nantucket, and Kajal has a pet cat named Birdie.

I don’t learn anything I want to know—and frankly, nothing I didn’t know already. Leonie’s family, the Schuylers, are old money; and I’d seen Leonie around school before, I realize, although she had straight hair then, and she certainly hadn’t been wearing that massive antique signet ring. The surnames Mehta and Kennedy are equally storied, their wielders frequent guests at my mother’s holiday home in Venice.

I want to know why they chose Godwin . . . or Dalloway altogether. I want to know if they were drawn here, as I was, by the allure of its literary past. Or if perhaps their interest goes back further, paging through the years to the eighteenth century, to dead girls and dark magic.

“What do you think of Dalloway so far?” Leonie asks. Asks Ellis, that is.

Ellis taps the ash from her cigarette into an empty teacup. “It’s fine. Much smaller than I expected.”

“You get used to it,” Clara says with a silly little giggle. More and more I dislike her; perhaps because she reminds me too much of Alex, and yet not enough of her, either. Clara and Alex look alike, but that’s where the similarities end. “You’re lucky to be in Godwin. It’s the best house.”

“Yes, I know about Dickinson,” says Ellis.

“Not just that,” Leonie says. “Godwin might be the smallest house on campus, but it’s also the oldest. It was here before the rest of the school was even built. Deliverance Lemont—thefounder—lived here with her daughter.”

“Margery Lemont,” Ellis says, and I am frozen in the armchair, ice water in my veins. “I read about what happened,” she adds.

I should have gone upstairs when I had the chance.

“Creepy, right?” Clara says. She’s smiling. I can’t help but stare at her. Creepy: the word fails to encapsulate what Margery Lemont had been. I can think of better terms: Wealthy. Daring. Killer. Witch.

“Oh, please,” Kajal says, waving a dismissive hand. “No one really believes in that nonsense.”

“The deaths were real. That much is a historical fact.”

Leonie’s tone is almost pedagogic; I wonder if her thesis involves archival work.

“Yes, but witchcraft? Ritual murder?” Kajal shakes her head. “More likely the Dalloway Five were just girls who were too bold for their time, and they were killed for it. Like what happened in Salem.”

The Dalloway Five.

Flora Grayfriar, who was murdered first, by the girls she’d thought were friends.

Tamsyn Penhaligon, hanged from a tree.

Beatrix Walker, her body broken on a stone floor.

Cordelia Darling, drowned.

And . . . Margery Lemont, buried alive.

Before last year, I had planned to write my thesis on the intersection of witchcraft and misogyny in literature. Dalloway seemed like the perfect place for it, the very walls steeped in dark history. I had studied the Dalloway witches like an academic, paging through the stories of their lives and deaths with scholarly detachment—until the past reached out from parchment and ink to close its fingers around my throat.

“You’re lucky you got accepted to Godwin your first year at Dalloway,” Leonie says to Ellis, deftly guiding the conversation out of choppy waters. “It’s so competitive; most people don’t get accepted until they’re seniors.”

“I’m a junior,” Clara points out, to general disregard.

I resist the urge to retort: I was, too.

“Didn’t they say all the witches died here at Godwin House?” Ellis says, lighting a fresh cigarette. The smell of her smoke curls through the air, acrid as burning flesh.

I can’t be here.

I shove back my chair and stand. “I think I’ll head to bed now. It was lovely meeting all of you.”

They’re staring at me, so I force a smile: polite, good girl, from a good family. Ellis exhales her smoke toward the ceiling.

By the time I make it upstairs to my dark room and its old familiar shapes, I’ve identified the feeling in my chest: defeat.

The tarot cards are still on my bed. I grab the deck and shove it back into the hole it came from, push the baseboard into place.

Ridiculous. I’m ridiculous. I should never have used them again. Tarot isn’t magic, but it’s close enough; I can practically hear Dr. Ortega’s voice in my head, murmuring about fixed delusions and grief. But magic isn’t real, I’m not crazy, and I’m not grieving.

Not anymore.

I debated attending the party at all. The inhabitants of Boleyn House throw the same soiree at the start and finish of every semester—Moulin Rouge themed, girls with long cigarette holders sipping absinthe and checking glued-on lashes in the bathroom mirror—and I’d always attended before. But that was when I had all of Godwin House with me. Alex and I used to dress monochrome: me in red, her in midnight blue. She’d have a hip flask tucked into her beaded clutch. I’d lean out the fourth-story window and chain-smoke cigarettes—the only time I ever smoked.

This time it’s just me. No dark mirror-self. And the red dress I wore last year hangs off me now, my collarbone jutting like blades from shoulder to shoulder and my hip bones visible through the thin silk.

I recognize some of the faces, students who had been first-years and sophomores during my first attempt at a senior year; they wave at me as they drift past, on to more promising prospects.

“Felicity Morrow?”

I glance around. A short, bob-haired girl stands at my elbow, all big eyes and wearing a dress that has clearly never seen an iron in its life. It takes a second for the realization to sink in.

“Oh—hi. It’s Hannah, right?”

“Hannah Stratford,” she says, beaming still wider. “I wasn’t sure you’d remember me!”

I do, although only as a vague recollection of the little first-year who’d tagged along after Alex like Alex was the very embodiment of sophistication and not a messy girl who always slept too late and cheated a passing grade out of French class. No, outside of Godwin House, Alex was seamless, refined, the model of effortless perfection, who managed to wear her parvenu surname like a goddamn halo.

My stomach cramps. I press a hand against my ribs and suck in a shallow breath. “Of course I remember,” I say, drawing a smile onto my lips. “It’s good to see you again.”

“I’m so glad you decided to come back this year,” Hannah says, solemn as a priest. “I hope you’re feeling better.”

All at once, that smile takes effort. “I’m feeling fine.”

It comes out sharply enough that Hannah flinches. “Right. Of course,” she says hurriedly. “Sorry. I just mean . . . sorry.”

She doesn’t know about my time at Silver Lake. She can’t possibly know.

Another breath, my hand rising and falling with my diaphragm. “We all miss her.”

I wonder if it sounds disingenuous coming from my mouth. I wonder if Hannah hates me for it, a little.

Hannah chews her lower lip for a moment, but whatever she’d thought of saying she abandons in favor of another bright grin. “Well, at least you’re still in Godwin House! I applied this year, but no go, unfortunately. But then again, everyone applied. I mean, obviously.”

Obviously?

I don’t even have to ask the question. Hannah rises up on the balls of her feet, leans in, and whispers it like a secret: “Ellis Haley.”

Oh. Oh. Mismatched puzzle pieces slide, at last, into place. Ellis is Ellis Haley. Ellis is Ellis Haley, novelist: bestselling author of Night Bird, which won the Pulitzer last year. I’d heard about it on NPR; Ellis Haley, only seventeen and “the voice of our generation.”

Ellis Haley, a prodigy.

I manage to say, “Isn’t she homeschooled?”

“That’s right. You wouldn’t know, I guess. She transferred here this semester, for her senior year. I suppose she wanted to get out of Georgia.”

Hannah is still talking, but I don’t really hear her. I’m too busy combing through my memories of the past week, trying to remember if I did anything humiliating.

Everything I’d done was humiliating.

“I’m going to get a drink,” I tell Hannah, and escape before she can announce she’ll join me. The only thing worse than listening to Hannah tell me how sorry she is about what happened would be listening to her wax rhapsodic about Ellis Haley.

The Boleyn girls have set up a makeshift bar in their kitchen, their faculty adviser conveniently absent—as all our faculty go conveniently absent whenever we throw parties; our parents don’t pay this school to discipline us after all—andthere are more varieties of expensive gin than I know how to parse. I pour myself a glass of what’s closest, then a second glass when that one’s gone.

I don’t even like gin. I doubt that any of the twenty girls who live in Boleyn House like gin; they just like how much this particular gin costs.

No one talks to me. For once, I’m glad. Instead I get to watch them talk to each other, their sidelong glances skirting past me like they’re trying not to be caught looking, conversation dropping low when they realize I’m there.

Everyone knows, then.

I don’t know how they figured it out—or, well, maybe I do. Gossip travels fast in our circles. Even with Ellis Haley at Dalloway School, I am the most interesting person here.

I tip back the rest of my drink. They’ll get over it. Once classes start, someone will invent a worse story to tell around the fireplace than Felicity Morrow, the girl who . . .

Even in my mind, I can’t say it.

I pour myself another glass.

Every house at Dalloway has its secrets, a relic of the school’s history. As Leonie had so astutely pointed out, Dalloway was founded by Deliverance Lemont, the daughter of a Salem witch and allegedly a practitioner herself. Some secrets are easier: a secret passageway from the kitchen to the common room, a collection of old exam papers. Boleyn’s, like Godwin’s, is darker.

Boleyn’s secret is an old ritual, a nod from the present day to a time when bad women were witches and passed their magic down to their daughters, generation to generation. And if the magic has died by now, diluted by technology and cynicism and too many years, students of certain Dalloway houses still honor our bloody inheritance.

Boleyn House. Befana House. Godwin.

When I was initiated into the Margery coven, I pledged my blood and loyalty to the bones of Deliverance’s daughter, the dead witch Margery Lemont. I might not be part of Boleyn House, but the initiation ritual bound me to five girls each year from these three houses, chosen to carry Margery’s legacy.

More or less, anyway; last year I saw one of the Boleyn initiates drinking tequila out of the Margery Skull’s eye socket like it was a particularly macabre sippy cup.

The Skull is supposed to be here, at the Boleyn House altar. I could drift down the hall with gin running hot in my veins, find the girl in red standing guard by the crypt door, and murmur the password:

Ex scientia ultio.

From knowledge comes vengeance.

I close my eyes, and for a moment I can see it: the single slim table draped in black cloth and bearing thirteen black candles. The thirteenth candle atop the Margery Skull, wax melting over its crown like a dark hand grasping bone.

But the Skull isn’t there anymore, of course. It’s been missing for almost a year.

None of the Boleyn girls seem concerned. Even the girls I recognize from previous visits to the Boleyn crypt are drunk and laughing, liquor sloshing over the rims of their cups. If they worry about a dead witch seeking revenge for her desecrated remains, it doesn’t show.

We’ve all heard the ghost stories. They’re told at Margery coven initiation rites, handed down from older sister to younger like a family heirloom: Tamsyn Penhaligon seen outside a window with her snapped neck, Cordelia Darling with her sodden clothes dripping water on the kitchen floor, Beatrix Walker murmuring arcane words in the darkness.

Tales meant to frighten and entertain—not meant to be believed. And I hadn’t believed. Not at first.

But I still remember the dark figure blooming from the shadows, the guttering candlelight, and Alex’s white, stricken face.

I turn and stalk down that hall toward the crypt. The girl in red is there, but she isn’t the somber, stoic figure she ought to be. She’s on her phone, tapping away at the screen, which lights her face in an eerie bluish glow, smirking at something she’s just read.

“Remember me?” I say.

She looks up. The grin drops from her face between one heartbeat and the next, a new expression stealing its place: something flat and guarded and hard to read. “Felicity Morrow.”

“That’s right. I’ve been enjoying the party.”

Her weight shifts to the other foot, and her arms rise to hug around her waist, fingertips pressing in against that red cardigan. “I heard you were back at school this year.”

She’s afraid of me.

I shouldn’t blame her for it, but I do. I hate her, all at once. I hate that she is the one standing in scarlet to guard the crypt, I hate the invisible threads that tie her to the other girls in our coven, the knots between her and Bridget Crenshaw and Fatima Alaoui and the rest of them, tethers I used to think were unbreakable.

I hate that I don’t even remember her name.

“I haven’t received a note yet,” I say.

She shakes her head very slightly. “You won’t be getting one. Not this year.”

I knew it. I guessed it when none of them wrote to me while I was gone, despite all those flowers they sent to Alex’s mother for the funeral, their figures like a murder of crows huddled at Alex’s grave site even though none of them knew her. None of them really knew her, not like I did.

Suddenly I’m coldly, brutally sober. I set my empty glass aside on the nearest table and look at this girl with her scarlet Isabel Marant sweater and expensive manicure, her lipsticked mouth that would have whispered about Alex when she thought Alex couldn’t hear: scholarship, rustic, aspirant.

“I see,” I say. “And why is that?”

She might be afraid of me, but now it’s for a different reason entirely. I know how to adopt my mother’s crisp consonants and Boston vowels to effect. It’s an introduction without ever having to repeat my name.

The girl’s cheeks flush as red as her cardigan. “I’m sorry,” she says. “It wasn’t my decision. It’s just . . . you took this all so seriously, you know.”

It’s a comment that demands a response, but I find myself voiceless. So seriously. As if the skull, the candles, the goat’s blood . . . as if that was all a joke to them.

Or maybe it was. Alex would have said that witchcraft was about aesthetics. She would tell me that this coven was created for sisterhood—for the Margery girl with a knowing smile at that corporate gala introducing you to the right person at the right time. Connections, not conjure.

My smile feels tight and false on my lips, but I smile all the same. That’s all we ever do at this school: insult each other, then smile.

“Thank you for the explanation,” I say. “I understand your position completely.”

Time for another drink.

I make my way back into the kitchen, where the gin has been replaced by an unfamiliar green drink that tastes bitter, like rotten herbs. I drink it anyway, because that’s what you do at parties, because my mother’s blood runs in my veins and, like Cecelia Morrow, it turns out I cannot face the real world without the taste of lies in my mouth and liquor in my blood.

I hate that it’s true. I hate them more.

My thoughts have finally tilted hazy, all blue lights and blurred shapes, when I see her. Ellis Haley has arrived, and she’s brought her new cult in tow: Clara and Kajal and Leonie. None of them dressed for the theme, but somehow they become the knot around which the rest of the party shifts and contorts. I’m no better. I’m staring, too.

Ellis is wearing lipstick for the occasion, a red so dark it’s almost black. It will leave a mark on everything her mouth touches.

Our eyes meet across the room. And for once I’m not even tempted to turn away. I lift my chin and hold her gaze, sharp beneath straight brows, somehow clear despite the empty absinthe glass she holds in hand. I want to crack open her chest and peer inside, see how she ticks.

Then Ellis tilts her head to the side, bending down slightly as Clara rises up to murmur something in her ear. That rope tethered between us draws taut; she doesn’t look away.

But I do, just in time to catch the twist to Clara’s pink lips, the brief and brutal gesture with two fingers: scissors snapping shut.

Something cold plunges into my stomach; even chasing it with the rest of my drink doesn’t thaw the ice. I abandon my empty glass on the table and push my way through the crowd, using elbows where words fail.

I make it all the way outside before lurching forward to spill my guts across the lawn. I’m still gasping, spitting out bile, as someone yells from the porch: “Go to rehab!”

Oh. Right. It’s only nine p.m.

I wipe my mouth on the back of a shaky hand, straighten up, and dart down the walkway toward the quad. I don’t look back. I don’t let them see my face.

At Godwin House I brush my teeth, then pace the empty halls, a terrible restlessness crawling up and down my spine. I can’t sleep yet. I can’t climb into my chilly bed and stare at the wall, waiting for the rest of them to get home, craning my ears to hear the sound of my name on their lips.

I make a cup of tea instead, stand at the kitchen counter sipping it until some of that dizzy drunk feeling fades. That gets me to nine-thirty, and then I have to put the dishes away and figure out something else. I draw a three-card tarot reading: all swords. I glimpse a light on, through the crack beneath Housemistress MacDonald’s door, but I’m not quite so pathetic yet as to seek her company.

As usual I end up in the common room.

The problem is, I don’t have anything I want to read. I peruse the shelves, but nothing jumps out at me. I feel as if I’ve read everything—every book in the world. Every title seems like a reiteration of something that came before it, the same story regurgitated over and over.

I make a fine literature student, don’t I?

This house seems too quiet now. The silence bears down on me like a weight.

No, it is too quiet—it’s unnaturally quiet—and when I glance back I see why.

The grandmother clock that sits between the fiction and poetry shelves has gone silent. Its hands are stuck at 3:03.

The same time I had the nightmare.

I draw closer, steps slow. The floorboards creak under my weight. I stare at the white face of that clock, at those black blades pointing nearly at a right angle to each other, mocking me. The silence thickens. I can’t breathe; I’m suffocating in thin, depressurized air—

“I suppose we’ll have to get it repaired,” someone says, and I spin around.

Ellis Haley stands behind me, both hands tucked into her trouser pockets and her attention fixed past me at the grandmother clock. She’s still wearing that red lipstick, the lines of it too crisp and perfect to have just come from a party. After a moment her gaze slips down to meet mine.

“You left early,” she comments.

“I felt sick.”

“They didn’t sweeten the absinthe enough,” she says, and shakes her head.

For a second we both stand there staring at each other. I remember Clara’s pale hands in the darkness: snip, snip.

“Where’s everyone else?” I ask.

“Still at Boleyn, as far as I know. I came back alone.”

I struggle to imagine any of those girls letting Ellis Haley go anywhere by herself. You must’ve had to peel them off like tiny well-dressed leeches.

I realize I’ve said that out loud, a beat after my mouth falls shut again.

Ellis laughs. It’s a sudden bright sound that breaks the silence like an egg, that fills the room. “I did tell them I was just going to freshen up,” she admits. Her eyes crinkle at the corners when she smiles. “Clara tried to come with me.”

“How fortunate you managed to escape.”

“By a hair,” Ellis says, pinching her fingers. “I made coffee, by the way. Would you like some?”

“It’s late for coffee, isn’t it?”

“It’s never too late for coffee.”