9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

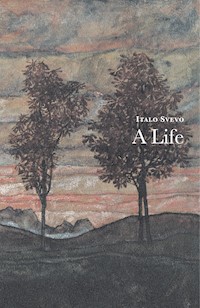

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Alfonso the bank clerk wants to be a poet and seems to be falling in love with Annetta, the vain and arrogant daughter of his boss. But the emptiness of his attempts at both writing and love lead to an ironic and painful conclusion.A Life is the gruelling tale of the frustrated existence of a bank clerk with a poetic soul. The artistic aspirations of the protagonist and the emptiness of his daily life become tragic in the great divide between what he wants and what he actually has and gets.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Ähnliche

ITALO SVEVO

A LIFE

Translated from the Italian by Archibald Colquhoun

Contents

Title Page

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

Also Available from Pushkin Press

About the Publisher

Copyright

A LIFE

I

Mother dear,

Your sweet letter only reached me last night.

Don’t worry about your handwriting; it has no secrets for me. Even when there’s some word that’s unclear, I can make out what you mean when your pen runs on, or think I do. I re-read your letters again and again; they are so simple, so good; just like you.

I even love that paper you use! I recognize it; it’s sold by old Creglingi, and brings back to mind the main street of our village back home, twisty but clean. I can picture where it broadens into an open space with, in the middle Creglingi’s shop, a low little place with a roof like a Calabrian hat. He is inside, busy selling papers, nails, grog, cigars or stamps, slow but flustered, like a man in a hurry, serving ten customers or really only serving one while keeping a wary eye on the other nine.

Do give him my regards, please. Whoever’d have thought I’d ever want to see that crusty old miser again?

Now, Mother, you mustn’t think it’s bad here; I just feel bad myself! I can’t get used to being away from you so long. What makes it worse is the thought of you being lonely in that big place so far out of the village where you will insist on staying just because it belongs to us. And I feel such a need to breathe some of our good pure air coming straight from its Maker. Here the air is thick and smoky. On my arrival I saw it hanging over the city like a huge cone, like winter smoke in our fireplace at home, but we know it’s purer there at least. The other men here are all or nearly all quite content, not realizing one can live so much better elsewhere.

I felt happier here as a student, because my father was still alive and made much better arrangements for me than I ever realized! Of course he had more money. My room is so tiny it makes me miserable. At home it could be a goose-run.

Mother, wouldn’t I do better at home? I can’t send money because I have none. On the first of the month I was given a hundred francs; that may seem a lot to you, but here it goes nowhere. I try as hard as I can, but the money won’t do.

I’m beginning to realize, too, how hard it is to get on in business, just as hard as to study, as our notary Mascotti says. Very hard indeed! My pay may be envied, and I realize I don’t earn it. My fellow lodger gets one hundred and twenty francs a month; he’s been at Maller’s for about four years and does workwhich I could only take on in a year or two. I’ve no hope or chance of a rise in pay before.

Wouldn’t I do better at home? I could help you, work in the fields myself even, and get a chance to read poetry in peace under an oak tree, breathing that good undefiled air of ours.

I want to tell you all about everything here! My troubles are made worse by the way my colleagues and superiors treat me. Maybe they look down on me because I don’t dress well. They’re just coxcombs, the lot of them, who spend half their day in front of their mirrors. An ignorant lot! Why, if someone handed me any Latin classic, I could comment on it all; but they wouldn’t even know its name.

There, those are my troubles, and one word from you can cancel them all. Say the word, and I’ll be with you in a few hours.

After writing this letter I feel calmer, as if you’d already given me permission to leave and I were about to pack.

A hug from your affectionate son,

Alfonso

II

AS SIX O’CLOCK FINISHED STRIKING, Luigi Miceni put down his pen and slipped on his overcoat, short and smart. On his desk something seemed out of order. He arranged the edges of a pile of papers exactly in line with it. Then he glanced at the order again and found it perfect. Papers were arranged so neatly in every pigeon-hole that they looked like booklets; pens were all at the same level alongside the ink pots.

Alfonso had done nothing but sit at his place for half-an-hour and gaze at Miceni with admiration. He could not manage to get his own papers in order. There were a few obvious attempts at arranging them in piles, but the pigeon-holes were in disorder; one was too full and untidy, the other empty. Miceni had explained how to divide papers by content or destination, and Alfonso had understood, but, from inertia after the day’s work, he was incapable of making any more effort than was absolutely necessary.

Miceni, when just about to go, asked him, “Haven’t you been invited round by Signor Maller yet?”

Alfonso shook his head; after his outburst in that letter to his mother such an invitation would have been a nuisance, nothing more.

Miceni was the reason Alfonso had alluded in his letter to the haughtiness of his superiors, for this invitation was often mentioned by Miceni. It was customary for every new employee to be invited home to the Mallers, and Miceni was sorry Alfonso had not been asked, as this first omission might mean the end of a custom to which he was attached.

Miceni was a frail young man with an unusually small head covered with very short curly black hair. He dressed as if he could allow himself a few luxuries and was as neatly kept as his desk.

It was not only in dress that Alfonso differed from his colleague. He was clean, yet everything he wore, from his freshly-ironed but yellowish collar to his grey waistcoat, showed untrained taste and a wish to avoid spending. Miceni, who was vain, would tease him by saying that his only luxuries were his bright blue eyes, their effect spoiled, according to Miceni, by a thick, ill-kept, chestnut-coloured beard. Though tall and strong, he seemed too tall when standing, and, since he held his body bent slightly forward as if to ensure balance, he looked weak and rather vague.

Sanneo, the head of the correspondence department, now hurried in. He was about thirty, tall and thin, with light, faded hair. Every part of his long body was in constant movement; behind his glasses moved pale restless eyes.

He asked Alfonso for a book of addresses and, as the word did not occur to him at once, tried to show the shape of the book with his hands, trembling with impatience. On getting it, as he was nervously flicking over the pages, he gave Miceni a polite smile and asked him to stay on as he had more work for him. Miceni at once took off his overcoat, carefully hung it up, sat down, took his pen and awaited instructions.

Alfonso did not like Signor Sanneo’s brusqueness, but he had to admire him. Very active, though physically weak, Sanneo had a formidable memory and knew the tiniest detail of every little business deal, however long ago. Always alert, he wielded his pen with speed and ability. On some days he would work ten hours nonstop, indefatigably organizing and registering. He would discuss some petty detail intensely, as Alfonso knew from copies of letters he happened to see.

“Why does he put so much into it?” Alfonso would ask himself, not understanding the other’s passion for his work.

Sanneo had a defect which Alfonso learnt of from Miceni. He was inclined to pick favourites capriciously and persecute those out of favour. He seemed quite incapable of liking more than one person in the office at a time. Just then his favourite was Miceni.

Signor Maller opened the door and, after making sure Sanneo was there, entered the room. Alfonso had never seen him before. He was thick-set, rather tall. His breathing could be heard at times, though he did not suffer from shortness of breath. He was almost bald, with a thick beard, cut short, fair to red. He wore gold-rimmed glasses. Red skin gave his head a rather coarse look.

He did not glance at the two clerks, who had got to their feet, or answer their greeting. Handing a telegram to Sanneo with a smile, he said: “The Mortgage Bank! We’re in on it!”

This message from Rome had been expected for days and meant that Maller & Company was entrusted with underwriting the share issue for the new Mortgage Bank.

Sanneo understood and went pale. That message deprived him of the hours of rest on which he had counted. He controlled himself with a great effort and stood listening attentively to the instructions given him.

The issue was to take place two days later, but Maller & Company had to know the names of subscribers by tomorrow evening. Signor Maller mentioned some companies to which he particularly wanted offers sent. Others were to be addressed to clients to whom other similar offers had already been made. That very night some hundred telegrams were to be sent, prepared many days in advance without addresses and leaving blank the number of shares, which were to vary according to the importance of the company. But the work which would so prolong office hours consisted of letters of confirmation to be written out and dispatched at once.

“I’ll be back at eleven,” concluded Signor Maller. “Please leave on my desk a list of the companies telegraphed and a note of the number of shares offered them, and I’ll sign the letters.”

He went off with a polite greeting not addressed to anyone in particular.

Sanneo, who had now had time to resign himself, said jovially to the two young men, “I hope we’ll be done by ten o’clock or before, so that when Signor Maller gets back he’ll find the offices empty. Now to work.”

He told Miceni to tell the other correspondence clerks and Alfonso, the dispatch clerk, about the new task, then hurried out.

Miceni re-opened his closed ink-pot, took a packet of writing paper from a drawer and flung it on the table.

“If I’d gone off punctually on my own business, they’d never have laid hands on me to make me spend the night here.”

Alfonso walked off with a yawn. A dark narrow passage joined his room to the main corridor of offices, still lit, with doors all alike of black frames and frosted glass. Those of Signor Maller and Signor Cellani, the legal adviser, had their names in black on a gilt slip. In the harsh light the deserted corridor, its walls painted in imitation marble, the door jambs shadowless, looked like one of those complicated studies in perspective, made only of lines and sight.

At the end of the passage was a door smaller than the others. Opening this and leaning against the door post, Alfonso called, “Signor Sanneo says we’re all staying till ten tonight.”

“What?”

The question was equivalent to a reply. Alfonso entered the room and found himself facing a thick-set youth with wavy chestnut hair and a low but well-shaped forehead, who had got to his feet and was leaning in a defiant attitude, with fists clenched defiantly, on the long table at which he wrote.

This was Starringer, who had rejected all other promotion to take the vacant post as dispatch manager, thus getting at once the higher pay he urgently needed.

“Till ten? When do we eat then? I’ve worked all day and have a right to leave. I’m not staying!”

“Shall I tell Signor Sanneo that?” asked Alfonso timidly, always timid with those who were not.

“Yes … no, I’ll tell ’im myself!” That resolute “Yes” meant that he was off whatever the consequences; the rest he said in a lower tone. Then suddenly he realized that he could not avoid this new chore and burst into a violent rage. He blamed the correspondence clerks, yelled that when he himself was a clerk (a period he often referred to), they all worked hard during the day but went home at regular hours in the evening. That day he had seen Miceni gossiping in the passage and twiddling at the lock on Ballina’s door. Why did they waste time like that? Scarlet in the face, veins swelling on his forehead, he advanced on Alfonso. When he spoke of the clerks, he held out an arm and pointed at the correspondence department. Alfonso explained that they were not being kept back for any normal work, but that a new job had been given them at the last minute. Starringer’s rage did not lessen, but he stopped shouting. “Ah, so that’s it!” he said, and he shrugged his shoulders exaggeratedly.

Letters written during that day lay on the table, some already sealed. Taking no more notice of Alfonso, Signor Starringer seized one, sat down and with a trembling hand copied the address into a book in front of him.

Sitting in the passage was a boy called Giacomo, who had joined the bank on the day after Alfonso. He was fourteen, but his pink and white skin and shortness made him look no more than ten. Although Giacomo laughed and joked all day with the other messengers, Alfonso was sure he was homesick for his native village of Magnago, and felt fond of him.

“Till ten tonight,” he said, touching his chin.

The boy smiled and looked flattered.

Signor Maller came out of his room. He had put on his overcoat, and its cape was hanging from his shoulders. This made him seem taller and slimmer. Alfonso said “Good evening,” and Signor Maller replied with a nod to him and Giacomo. He had a way of making collective greetings.

Santo, Signor Maller’s personal messenger, followed his master along the length of the passage to open the front door for him. He was a little man, not old, bald and with a fair beard colourless in patches. People said he led an idle life, as he had nothing to do but look after Signor Maller, while other messengers served the offices.

On returning to his own room, Alfonso found Miceni already writing away. The latter was rather short-sighted and almost touched the paper with his nose as he wrote.

The telegrams, written out but unaddressed, were on Alfonso’s desk; so was a letter in Signor Sanneo’s handwriting to be copied in confirmation, and finally a list of five companies to which offers were to be sent.

“Only five?”

“Yes,” replied Miceni. “The pay-clerks are writing some out too. We’ll be done by half-past nine or so.”

He had not raised his head; his pen continued running on over the paper.

Alfonso put an address on a telegram, then transcribed it on to a letter. He began reading the telegram; it gave a brief account of why the Mortgage Bank was founded and hinted discreetly at a promise of Government support and mentioned how difficult it was to join the syndicate. “We offer you as priority …”, and a blank space followed, which Alfonso filled in with the number of shares offered. The letter was much more detailed. It went into the need for new large banks in Italy, and how the new bank was therefore certain to flourish.

Miceni told him to jot the first letter down fast as it was to be written out by the other clerks, but Alfonso was incapable of copying fast. He had to re-read every phrase a number of times before transcribing it. Between words he would let his thoughts run on to other subjects and then find himself with pen in hand, forced to cancel some part in which he had absent-mindedly deviated from the original. Even when he managed to turn his whole attention to his work, it did not proceed with the speed of Miceni’s because he could not get the knack of copying mechanically. When he was attentive, his thoughts were always on the meaning of what he was copying, and that held him up. For a quarter of an hour nothing was heard but the squeak of pens and from time to time the sound of Miceni turning pages.

Suddenly the door opened with a crash. On the threshold, standing rigid for an instant or two, appeared Ballina, the clerk who was waiting for Alfonso to hand over Sanneo’s letter so that he could make other copies from it.

“What about that letter?”

He was a handsome fellow with a clever, rather sly look, a pair of Victor Emmanuel moustaches, but with an untrimmed beard. He was smoking, and the smoke he did not blow away—he would gladly have absorbed it to relish it the more—was filling his moustaches and covering his face to the eyes. His working jacket must once have been white, but was now dirty yellow, except for the cuffs which were quite black from nib cleaning. He worked in a little room with a door on to the small passage, like Miceni’s room.

Miceni raised his head with a friendly smile. Ballina was always popular, as he was a jester, the bank jester. But that evening he was not in form and was complaining. He had been working in his information office till then, and now he found he had to do other work; he did not even know if there would be any supper left for him that night. He was pretending to be more miserable than he really was. He once amazed Alfonso, whom Ballina called a sponge, by telling him that towards the end of the month he lived on Scott’s Emulsion given him by a doctor relative. He had well-to-do relatives who must have been a help because he was always speaking well of them.

Sanneo came in, rushed as ever; he was followed by the serious adolescent’s face of Giacomo, carrying a big pile of paper at which he was staring with excess of zeal.

Sanneo asked Ballina rather roughly why he was not yet writing.

“Well …” exclaimed Ballina with a shrug, “I’m waiting for the letter to copy out.”

“You’ve not had it yet?” Then, remembering that Alfonso was supposed to hand it over, he went on, “Hasn’t he done even one yet?”

Alfonso, shaken by the Sanneo’s angry look, rose to his feet. Miceni, still sitting, observed that he had not yet finished one either. Sanneo turned his back on Alfonso, looked at Miceni’s letter and asked him to hand it over to Ballina as soon it was done. He went out in the same rush, preceded by Ballina, who wanted to show that he had gone straight back to his own room, and followed by Giacomo strutting and banging his feet on the floor to make himself sound important.

A few minutes later Miceni handed Ballina the letter for copying. From the next room Alfonso heard Ballina’s curses, his voice thick with rage at seeing that the letter covered four pages.

In an hour or so Miceni had finished his work. Very calmly he settled his clothes, carefully put on his hat as though he would never take it off, picked up the telegrams and letters—including the two written by Alfonso—which he wanted to hand over to Signor Sanneo as he passed, and left humming.

In the complete quiet work went faster. To keep his attention on his work, Alfonso was in the habit when alone of declaiming aloud, for lack of anything more interesting, the letter he was writing. This one was particularly suitable for declamation as it was full of reverberating words and big figures. By reading out a phrase and repeating it as he transcribed it, he reduced the effort of writing because he needed only the memory of the sound to direct his pen.

To his surprise he suddenly found that he had finished and went straight off to Sanneo, fearing he was already late. Sanneo kept the telegrams and told him to put the letters on Signor Maller’s desk.

The floor of Signor Maller’s room was covered with grey carpets during the winter. The furniture was also dark grey, with arms and legs of black wood. Of the three gas brackets only one was lit, and at half pressure. In the dimness the room looked gloomier than ever. Alfonso always felt ill at ease there. He put down the letters on top of another pile already on the desk for signature and went out without making a sound, as if his chief had been present.

He could have left now but was held back by exhaustion. He thought of putting his desk in order but sat there inert, daydreaming. Ever since he had become a clerk, deprived of the physical exercise of country life and mentally stifled in his work, his great vitality had taken to creating imaginary worlds.

The centre of these dreams was Alfonso himself, all self-mastery, wealth and happiness. Only when daydreaming was he aware of the extent of his ambitions. To make himself into someone overwhelmingly clever and rich was not enough. In his dreams he changed his father. Unable to bring him back to life, he turned him into a rich nobleman who had married his mother for love, though Alfonso loved her so much that even in his dreams she was left as she was. Actually he had almost entirely forgotten his father, which accounted for his giving himself the blue blood needed for his daydreams. He would picture himself meeting Maller, Sanneo, Cellani with that blood and those riches. Then, of course, roles were entirely reversed. It was no longer he but they who were timid! But he treated them graciously, with true nobility, not as they had treated him.

Santo came to warn him that Signor Maller was asking for him. Surprised and rather alarmed, Alfonso returned to the room where he had been shortly before. Now it was all lit up; his chief’s bare head and red beard glistened in the glare.

Signor Maller was sitting with both hands on his desk.

“I’m glad to see you’re still here, a proof of diligence, which anyway I’d never doubted.”

Remembering Sanneo’s outburst a short time before, Alfonso glanced at him fearing that he was being ironic, but his chief ’s red face was serious, with blue eyes staring at a far corner of the desk.

“Thanks!” muttered Alfonso.

“I’d be pleased if you could come to my home tomorrow evening for some tea.”

“Thanks!” repeated Alfonso.

Suddenly Maller, as if he’d had difficulty in making up his mind, looked at him and spoke less carelessly.

“Why d’you make your mother desperate by writing to her that you’re not content with me or with you? Don’t look so surprised! I’ve seen a letter from your mother to our housekeeper. The good lady complains a lot about me, but about you too. Read it and see!”

He proffered a piece of paper which Alfonso recognized as coming from Creglingi’s shop. A glance told that it really was in his mother’s handwriting. He blushed, ashamed of the ugly writing and bad style. In some vague way he felt offended that the letter was being made public.

“I’ve changed my mind now,” he stuttered. “I’m quite content! You know how it is … distance … homesickness …”

“I understand, I understand! But we’re men, you know!” He repeated the phrase a number of times, then warmly assured Alfonso that he was well-liked in the office not only by himself and Signor Cellani but by the head of the correspondence department, Signor Sanneo, and by everyone else, all of whom hoped to see him make rapid progress. In dismissing him Signor Maller repeated, “We’re men, you know!” and gave him a friendly nod. Alfonso went out, feeling confused.

He had to admit that Signor Maller seemed decent enough, and easily impressed, Alfonso felt his position in the bank to be improved; at last someone was taking notice of him!

But he regretted not having behaved more frankly and sincerely; why had he denied truths confessed to his mother? He should have answered his chief’s kindness by telling him frankly of his hopes, and thereby had some chance of seeing some of them satisfied; anyway he would have got on to friendlier terms, since no one is ever offended by being asked for protection. He told himself he would be more frank on some other occasion, which would soon come up after this.

Meanwhile, to avoid contradictions between what he had told Signor Maller and what he had written to his mother, he wrote to her again, saying that his prospects at the bank were improving and that for the moment he renounced open air, oak trees and rest. Either he would return home rich or never return at all.

III

THE LANUCCIS, with whom Alfonso lodged, lived in a small apartment in a house in the old town near San Giusto. From there he had more than quarter of an hour’s walk to the office.

Just before her marriage Signora Lucinda Lanucci had spent a summer in Alfonso’s village as housekeeper to a family. She had then made the acquaintance of Alfonso’s mother, who had recommended her son. This introduction from Signora Carolina might have been worthless had the Lanuccis not been looking for someone to rent a small extra room in their house. And so Alfonso came along at the right moment and was welcomed.

A few years before, seduced by a longing for independence, Signor Lanucci had left a job which was not particularly good but did keep his family adequately, and had begun acting as agent for a variety of companies representing almost every conceivable article. But though the poor man wrote off every day to companies whose addresses he took from the back pages of newspapers, he still earned less than he had before as a clerk. And so now the family’s finances were so precarious that their mood was sad.

This had increased Alfonso’s homesickness, for sad people make places sad.

They treated him affectionately, but Signor Lanucci aroused Alfonso’s pity, particularly when he saw the poor man making an effort to be polite, to smile and to show interest in his affairs, though Alfonso realized that he himself was only a source of revenue.

Signora Lanucci, long accustomed to consoling her husband for his fruitless efforts, soon assumed a similar attitude to Alfonso’s and came to take such an intense interest in the young man’s affairs that she spoke of them as if they were her own. Signor Maller’s invitation, which Alfonso mentioned, aroused a most flattering reaction in her; she spoke of it as if it were sure to make the clerk’s fortune; so little was she used to good fortune that it took her by surprise.

Lucinda was about forty but, being small and plump with thick grey hair, looked more. She had never been beautiful. The small dowry she had brought her husband had melted away in some speculation with Turkish shares. She was bright and lively and loved to talk; her pale suffering face had won Alfonso’s sympathy at once.

She seemed devoted to her husband; not so devoted, apparently, to her son Gustavo, aged eighteen, whom she called a rough diamond; her chief affection went to her daughter Lucia, aged sixteen, who did dressmaking in private houses. The mother earned more than all of them as a teacher in an elementary school, but they could not have made ends meet without Lucia’s earnings. Signora Lucinda was desperate at seeing her daughter forced to spend her youth at a sewing machine, while hers had been spent better, for she had come from well-to-do people and had studied and amused herself. Their means now were so narrow that she had been unable to do anything about Lucia’s education; but she did not complain of this, unaware that the results corresponded to the outlay. Intelligent though she was, Signora Lucinda did not notice how insipid her daughter’s prattle was. She saw her as beautiful, while actually Lucia was thin and anaemic like the rest of the family, with fair reddish colouring and, because of her thinness, a mouth that seemed to reach her ears. The mother’s behaviour was like that of a woman of the people, and she even swore, all quite deliberately, for she was an extreme democrat; her daughter had quickly picked up, from the middle-class homes she frequented, ladylike mannerisms quite out of place in her own home. Gustavo, rough and simple, often jeered at her for it, earning his mother’s dislike more by that than by his wastefulness.

Alfonso found his black suit laid out on the bed, carefully folded. Signora Lanucci had thought of everything, from tie to gleaming boots ready at the foot of the bed. Alfonso too felt excited by the visit he was about to make. Though he had not Signora Lanucci’s illusions about it, they were contagious, and he was more agitated than seemed necessary. He took off his everyday suit and flung it on the bed as though he would never have to put it on again.

On entering the small living-room where the family ate, he almost imagined himself to be really well dressed. Signora Lanucci looked at him and admired his appearance. Gustavo, filthy, came up to him with a benevolent smile, his mouth full. This young gentleman aroused no envy in him as his own desires were quite different: a few coins in his pocket for an evening at a tavern, no more. Gustavo was then attached to a copying office and apt to criticize his new job where there was little pay but a lot of work.

With his clean shirt, high collar, well-brushed thick hair, black suit, Alfonso looked quite handsome. He was holding in one hand some light-coloured gloves bought that day on Miceni’s advice. A more expert eye would have noticed shiny patches on the black suit, that its cut was not modern, its collar too open and of poor stuff that yielded to the stiff shirt. But the Lanuccis were not trained to such details.

Lucia had now stopped eating and moved a little away from the table, leaning on the back of a chair with crossed hands—she showed no sign of noticing Alfonso’s special outfit. They were on good terms, and when he was at home she served him willingly. She liked to make herself useful to him, because he always thanked her so pleasantly for all she did. Their exchange of courtesies verged on the excessive, now that she had at last found someone whom she could treat in the way she had noticed people treating each other in the homes where she worked. Her mother encouraged her. Gustavo would say that she was letting off steam on Alfonso.

Signor Lanucci must have been over fifty. He dyed his hair, because he had free samples of dye sent by companies he had offered to represent; his hair was black where it was not whitened by age, and yellowish where it would have been white without dye. He wore a long full beard, its colour blending with his hair. To read in the evenings he put on a clumsy pair of spectacles, so wide between his small grey eyes that they almost fell off his nose.

He complimented Alfonso and asked him to sit next to him, an honour no longer granted to Gustavo since the youth had lost the decent job they had obtained for him with great efforts. This was the only punishment the father could inflict, having neither brain nor energy for any other.

Gustavo, without a word—he had a grudge against his father for having one against him—handed Alfonso a letter. Alfonso did not open it very eagerly. So preoccupied was he that he had not the patience to decipher his mother’s shaky handwriting, and he put the letter back into his pocket after a quick glance.

“That didn’t take long!” said Signora Lanucci with a hint of reproval.

“It’s very short!” replied Alfonso flushing, “She sends you her best wishes.”

The old man had begun describing his day’s work. It was the same tale every evening. To justify himself to his wife he would describe how much he had canvassed for business. That day he had earned, all told, a big packet of needles sent by a small factory as agent’s fee for some business he had arranged for them. In the morning with a letter of recommendation from a friend who was a merchant and whom he considered to have influence in the town, he had called at a few private houses trying to sell Cognac, but without result. The sample made a show on the table. At midday he had got some mail, comprising that packet of needles and a letter from an insurance company making him their representative. That very afternoon the old man had set off in search of people willing to be insured, going round town with a list of acquaintances, which he always carried with him. Friends had explained that they did not want to be, already were or could not afford to be insured: others either did not see him—Lanucci liked calling on people who kept servants to open their front doors—or sent him off with a few dry words as to a beggar.

This comment was not Lanucci’s, who told his tale with the calm of perseverance, ready to begin all over again the next day. But later that day Lanucci had written to the insurance company telling them that, though he had not actually fixed anything yet, he still had high hopes, and that meanwhile the agent’s fee was too low in view of the difficulty of conducting business.

“Oh dear, that postage!” murmured Signora Lanucci with a wink at Alfonso, to whom she had already spoken of her husband’s hopes and manias.

But she had followed the account with close attention, and her eyes shone with indignation at all his vain efforts. Signor Lanucci spoke slowly, talking continually as he ate, putting his fork down after every mouthful and emphasizing each syllable to make his own activity and astuteness clearer. He repeated all the arguments he had used. To one person he had talked of the advantages of insurance in general and how wrong it was not to insure oneself, to another—some friend or known philanthropist—of his own need for encouragement. To all he had praised the company he represented. Signora Lanucci listened to him, sitting slightly back from the table, chewing little bits of bread very fast with her front teeth.

Any remark by his family was apt to provoke Signor Lanucci to argument.

“‘Oh dear, the postage,’ did you say? Why? You’ve an odd way of looking at things! Why, I couldn’t do any business at all …”

Resentment accumulated during the day now burst loose. He sat stock still in his chair, but his lips were trembling. Gustavo grinned into his plate.

Alfonso soothed the old man; he understood his anguish since he too found himself in financial straits from time to time. He told him that his wife was only joking and he must not take offence, and that she really longed to see his affairs prosper more than anyone.

Alfonso’s words started Lanucci on a completely different train of thought: for it now occurred to him that the comforter might become a client, and he began asking if Alfonso had ever had any idea of insuring himself—against accidents say?

Signora Lanucci protested.

“Oh! Can’t you leave him in peace with your business?”

Lanucci looked very put out: Alfonso was both embarrassed himself and distressed at the embarrassment of Lanucci, whom he supposed already regretted his tactless question.

“Do let him go on talking,” he said to Signora Lanucci. “He’s so interesting, and after all it costs nothing.”

He thus managed to reduce the matter to something purely academic.

“Yes, indeed!” emphasized Lanucci. “I’ll make him insure himself either through me or through somewhere else! He can do it wherever he likes. But anyone in a position to be insured does wrong not to be. Suppose a tile falls on his head? If he’s not insured, he earns nothing while in bed, but if he is, he’s in clover.”

To get out of it Alfonso now gave a frank account of his own finances. Signora Lanucci protested, and the old man calmly put up objections while still denying that a refusal needed any explanation.

Every evening the Lanuccis went out after supper to take some air. This was not the sole aim of the outing. Signora Lanucci had introduced the custom to compensate Lucia for the hour’s parade on the Corso with other young dressmakers, which she had made her give up. Gustavo accompanied them but did not come home with them. Sometimes Alfonso went, too, bored but making such a good pretence of being amused that in the end he believed it himself.

Signora Lanucci got up from table, put on a threadbare but heavy cloak, and stood waiting for Lucia to finish her far more complicated toilet. The old man, in an overcoat too small for him which his wife had helped him don, went on talking, still hoping to do some business before the day ended. But Alfonso, who had been on the point of giving way for an instant, now gave his exact salary and expenses in a slightly irritated tone, concluding that he could not dream of spending more. He expressed himself crisply to avoid finding himself in even worse financial straits; and, distrusting his own firmness, refused to hear any more argument. It seemed to him that Signor and even Signora Lanucci then said goodbye more coldly than usual, although the Signora did not omit wishing him good luck. Lucia gave him a bow, wished him a pleasant evening and held out her flaccid hand with a studied gesture.

Once alone, to let a little more time pass before going to the Mallers, who might not have finished yet, Alfonso read his mother’s letter.

Old Signora Nitti wrote of her hopes for Alfonso, and how she had written to Signorina Francesca Barrini, the Mallers’ housekeeper, to recommend him. The whole letter was scattered with greetings from friends in the village, patiently set down by the old lady with Christian name, surname and message: “sends lots of greetings”. Finally there were two lines of kisses and the signature—“your mother, Carolina”.

Beneath this, under P S , was the phrase: “I’ve not been very well for the last two days, but am better today.”

IV

ALFONSO CONSIDERED HIMSELF to have poise. In his soliloquies he certainly did. Having never had a chance of showing this quality to people whom he considered worthwhile, now, on his way to the Mallers, he felt as if a dream was about to come true. He had thought a lot about how to behave in society and had prepared a number of safe maxims to replace lack of practice. Speak little, concisely, and if possible well; let others talk, never interrupt; in fact be at ease without appearing to make any effort. He intended to show that a man could be born and bred in a village and, by natural good sense, behave like a poised and civilized townsman.

Signor Maller’s home was in Via dei Forni, a street in the new town, whose houses lacked any external charm. They were grey, with five floors and warehouses at street level. The street was badly lit and little frequented at night after the traffic of carts carrying merchandise ceased.

It had rained during the day, and Alfonso walked close against the walls to avoid mud. On finding the house, he was somewhat surprised by its entrance. This was lit up like broad daylight. Wide, divided into two parts separated by a staircase, it looked like a miniature amphitheatre. It was deserted, and as Alfonso went up the stairs, hearing nothing but the sound and echo of his own footsteps, he imagined himself the hero of a fairy story.

The first person to appear was a hale-looking old man with a well-trimmed white beard, who was humming as he came downstairs. “Who d’you want?” he asked, in a tone which was enough to show Alfonso that in spite of his black suit he could be recognized in that house as a poor man at first glance.

“Does Signor Maller live here?” he asked timidly.

The old man’s face became grimmer. Every decent person must know where Signor Maller lived. Could this be a beggar?

They were now on the last steps before the first floor. On the landing appeared Santo’s head, shaggy as a thistle.

“It’s one of our employees,” he called. “Come on up, Signor Nitti.”

“Oh, Santo!” exclaimed Alfonso, pleased to meet a face he knew, and he went up the stairs faster. The porter stroked his beard.

“Ah! So that’s who’e is, is it?” and the old man went on downstairs without any greeting, humming again after a few steps.

Santo, leaning negligently on the balustrade, waited for Alfonso without changing position and, when he was near, remarked, still motionless: “I’ll take you in.” Then, after a moment’s reflection, he asked: “Did Signor Maller invite you?”—a question which made Alfonso think that there must be a room set aside for employees invited by Signor Maller. Suddenly Santo began walking swiftly towards a door on the right.

“Excuse me a minute,” he called and, leaving him on the threshold, hurried into a passage, opened the first door he came to and slammed it behind him. Alfonso was left alone in a half-dark passage carpeted in muted colours with two doors on each side and one at the end, all small and made of shiny black wood. To the right he heard an outburst from Santo answered by a woman’s voice and laughter; he could make out no words, only the sound which rang as if in an empty space.

Then Santo came out roaring with laughter; his mouth was full. Through the half-shut door Alfonso glimpsed a kitchen with gleaming copper pots, a cooking-stove and next to it a blonde fat woman lit by a reddish glow from the stove; she was threatening Santo with a spoon. Santo went on laughing into his moustaches for a time, as he moved towards the door at the end of the passage.

They reached a square room with minute pieces of furniture made for creatures who had surely never existed. Small and soft as a nest, it was covered with blue stuff which Alfonso thought satin, and had carpets so thick and soft that he felt he wanted to lie down on them.

“This is Signorina Annetta’s little reception room,” said Santo, “but it’s not entered from this end. This is the servants’ entrance. I brought you this way to show you a few rooms at once; it’s the best part of the house.”

He looked at him with a patronizing smile, expecting thanks.

Various Chinese objects were laid out on a little table. Signorina Annetta’s taste was oriental, it seemed. By the light of Santo’s candle Alfonso saw a curtain with two small Chinese men painted on a blue background; one was sitting on a rope which was attached to two poles but slack and dangling as if the Chinaman had no weight, and the other was in the act of climbing an invisible cliff.

“The Signorina sleeps here,” said Santo when he reached the next room, holding his candle high to spread the light.

Alfonso asked in some disquiet: “Is one allowed to come straight in here like this?”

“No!” Santo replied grandly. “No one’s allowed but me.”

His face was agleam with pride at all this finery. He made Alfonso admire the velvet curtains, and even moved towards the bed and was about to open the dainty pink hangings around the four-poster, when Alfonso stopped him.

“Oh!” exclaimed Santo, with a gesture intended to show contempt for his employers’ wishes but belying his actions, added “Giovanna told me they’re all still in the living-room.”

Still, slightly shaken by Alfonso’s alarm, he moved towards the door. Alfonso, despite his agitation, found the bed touching and kept his eye on it until he reached the door. Next to it was a prie-dieu in dark wood.

In the next room he was surprised to find a library. Big shelves full of books covered the walls. The furniture was simple: in the middle a big table covered with green cloth and around the room comfortable chairs and two sofas.

Suddenly in came Signor Maller.

They had not heard his steps. He asked Santo brusquely what he was doing in that room.

“I wanted to show Signor Nitti the library,” stuttered Santo.

He had lost his easy, masterful bearing and stood rigidly at attention, holding his candle very low. Then he added, obviously lying: “We came in that way,” and pointed to a door in the middle.

Alfonso moved forward.

“I was on my way to disturb you …” and he interrupted himself, thinking he had already expressed all he wanted to say.

“Signor Nitti!” Signor Maller held out a hand with a polite gentlemanly gesture. “Welcome!” He spoke affably but with no great vivacity. “I’m sorry not to be able to remain with you as I would have wished; I have to see about a matter here and then leave. You’ll find my daughter and the Signorina, whom you already know, there in the living-room; goodbye for the moment,” and, half-turned towards the table already, he shook Alfonso’s hand.

Santo, rigid at the middle door, asked: “Shall I leave my candle here?”

“No, light the gas!”

Signor Maller lay down on the nearest ottoman and took up a newspaper.

Alfonso found himself in the passage by which he had entered. Helped by Santo, he took off his overcoat. While showing him into the living-room, Santo found time to exclaim: “What a pity we met Signor Maller; his bedroom’s worth seeing. Another time, perhaps,” and he gave a protective wink.

The living-room was lit by a gas-bracket with three flames. There was no one in it. Santo entered with cautious step, glanced round with a look of comical surprise, ran to a table, raised a corner of its covering, looked beneath: “No one here!”

Then, seeing Alfonso bored by this and not smiling at his jokes, he moved away.

“The ladies must have gone up to the second floor. I’ll go and tell them. Make yourself at home, meanwhile.”

Knowing the worth of Santo’s invitation, Alfonso remained standing. He was overawed by the wealth surrounding him and had forgotten all about behaving like someone with poise. He longed to be outside and did not feel at all happy, sensing he must have the modest bearing of an underling in this house. A more trained eye would have noticed something excessive in the decor, but it was the first time that Alfonso had seen such riches, and he was dazzled.

The living-room bore more traces of use than Annetta’s own rooms. A little piano was open with some music laid on it; sheets of music also lay on a chair near the instrument. The furniture was varied, some chairs wicker, some stuffed. He even sniffed a faint smell of food.

A large number of photographs were arranged like open fans on the walls above the piano. To leave room for the tall furniture the four or five pictures were hung too high.

Alfonso knew nothing at all about painting, but he had read a volume or two of art criticism and at least had an idea what the modern school meant in theory. He was struck by a painting representing nothing but a long road moving across a rocky landscape. There were no figures: just rocks and rocks. The colours were cold, and the road seemed to lose itself in the horizon. Its lack of life was disconcerting.

Lost in contemplation, more surprised than admiring, he did not hear the door open; then out of embarrassment he hesitated a little before turning when he realized that someone had entered the room.

“Signor Nitti!” said a gentle voice.

Red as if he had been standing on his head, Alfonso turned. It was the Signorina, as she was called, his mother’s friend, not Signorina Maller, who must be younger, but Signorina Francesca, whom he guessed to be about thirty, although he could not tell why he thought her as much as that. She had a pale complexion, not healthy but anyway young, and clear blue eyes; pale golden hair gave sweetness to her rather irregular features. In stature she was rather short, too short had her figure not been in perfect proportion and so dispensed with any wish to modify it.

She held out a plump white hand.

“You’re Signora Carolina’s son, are you not? And so a good friend of mine, eh?”

Alfonso bowed.

“Is everyone well in the village?”

She asked about a dozen people there, friends whom she had not heard mentioned for years, calling one or two by their nicknames, and mentioning some special characteristic of each. Then she asked about places, naming them with regret and citing happy hours spent there. She asked about a hill at the far end of the village and listened anxiously to his reply as though afraid to hear that it had fallen down in the meantime.

Alfonso found Signorina Francesca charming. No one had revived memories of his home in that way before; Signora Lanucci’s distant lifeless memories had revived nothing. He lived, dreaming sadly of his home, by himself, and transforming it by his very thoughts. The Signorina’s talk corrected his memories and seemed to give them a fresh impression. She was moved by them too.

As Alfonso soon learnt, that had been the happiest year of her life. She had been ill, and the poor family to which she belonged had made great sacrifices to carry out a doctor’s prescription and send her to the country. There she had enjoyed a year’s complete freedom.

She took his hat from his hand and made him sit down.

“Signorina Annetta will be here at once. Have you been waiting long?”

“Half-an-hour!” said Alfonso frankly.

“Who let you in?” asked the Signorina with a frown.

“Signor Santo.”

He said “Signor” out of respect for the person.

Signorina Annetta came in, and Alfonso rose to his feet in confusion, flustered by the long anticipation.

She was a pretty girl, although, as he told Miceni later, he did not find her wide pink face attractive. Tall, in a light dress which showed her pronounced curves to advantage, she was not a type to please a sentimentalist. With all her perfection of form Alfonso found her eyes not black enough and her hair not curly enough. He did not know why but he wished they had been.

Francesca introduced Alfonso. Annetta bowed slightly as she was about to sit down. Obviously she had no intention of saying a word to him. She began reading a newspaper that she had brought with her. Alfonso sensed that she was not reading and that her eyes were fixed on the same point on the page. He flattered himself that she was as embarrassed as he was and wanted to avoid showing it by this pretence of reading. But her face was calm and smiling.

Francesca, less relaxed, tried to start up the interrupted conversation again:

“And does your family still live in that house so far out of the village?”

Alfonso had scarcely time to say “yes”, when Annetta, with a little gurgle of pleasure, which she had been holding back with difficulty till then, said to Francesca: “I was with Papa. We’re leaving the day after tomorrow; he’s promised.”

Francesca seemed pleasantly surprised. Annetta’s voice amazed Alfonso; he had expected one less soft in so strong a frame.

The two women were talking in low voices. Alfonso guessed that Annetta must have used some guile to get some consent out of Signor Maller. Being quite in the dark about it all, he felt rather embarrassed. He looked at a picture to his right; a portrait of an old man with gross features, tiny eyes and a bald head.

Francesca seemed to sense that he was ill-at-ease and tried to make up for the discourtesy of Annetta, who had been the first to whisper. She told him how they had planned a trip to Paris, and now, after refusing for a long time, Signor Maller had finally agreed to go with them and leave his office for eight to ten days at the height of the business season. She turned back to Annetta.

“Did he definitely say I was to go with you?”

She must have been longing for that journey too.

“Of course,” replied Annetta, with a smile which Alfonso had to admit looked attractive.

For a space of time which seemed at least an hour he had to listen passively to the two women’s chatter, at times pretending to pay attention and at others turning modest eyes elsewhere when Annetta lowered her voice and neared her mouth towards Francesca’s ear. When Santo entered and announced Avvocato Macario, he felt relieved.

“Let him in, let him in!” cried Annetta joyously, “he’ll give us a laugh.”

Avvocato Macario was a good-looking man of about forty, dressed with great care, tall and strong, with a brown face full of life, and he greeted Annetta in imitation of Serravilla, “Even lovelier than usual today … ah!” He shook hands with Francesca, who at once introduced Alfonso and, instead of giving the lawyer’s name, said: “The finest moustaches in town!”

“If you knew what a bother it is to keep them like this; I must say that before the Signorina says it!”

Alfonso’s mouth tried to smile; he felt worse than before. Macario’s ease did not relax his embarrassment or make him feel any better.

Annetta had put down the newspaper. She leaned both her elbows lazily on the table.

“There’s some news, my dear cousin! It’ll surprise you!”

She had an air of deriding him.

Macario pretended to look put out.

“I know it already. In fact I’d never have believed it. Uncle leaving town at the height of the business season! Are these walls so solid that they don’t fall down from surprise? I met him on the stairs, and he told me the news, though with quite a different expression to yours now.”

He gesticulated as he spoke; at intervals he put his hands up close to his ears, as though hinting with an outstretched finger at things of which Alfonso knew nothing.

“I can understand your not being pleased about it,” said Annetta. “When one wants it here though,” and she touched her forehead with her forefinger, “that’s enough.”

Macario asserted that Paris was even more boring in the winter than in the summer. He seemed to be taking revenge for some little defeat; obviously he had tried to prevent this journey.

“In winter the Parisians always have their heads abuzz with something that makes them unbearable. Each year everyone in Paris, every single person, latches on to one subject. One day it’s the fall of the Ministry, another a Deputy’s speech, a third a murder. Always a bore!” he added.

Annetta recognized a novelist’s Paris in this description and exclaimed “Always charming!”

On a former journey she had searched in vain for that side of Paris.

“Each to his taste. If one visits a friend, he’ll talk about nothing but a pistol-shot fired at Gambetta; one arranges some business-deal, and the client is worrying about the pistol-shot and Gambetta; even the shoemaker talks of nothing but Gambetta. Maybe that’s all the better.”

At this joke Alfonso gave a loud laugh because he could find no words to put into the conversation and thought it a duty to show he was taking part.

“The Paris theatre’s all right in winter; a good première is worth the journey.”

Now Macario had set aside any attempt to diminish Annetta’s triumph and spoke seriously, turning to Alfonso, perhaps in thanks for the laughter.

“We’ll go to the première of Odette,” cried Francesca delightedly.

They would telegraph next day for seats.

Macario asked Alfonso whether he was employed by his uncle and for how long. On receiving a reply, he explained how on the stairs his uncle had told him he would find someone who dealt with correspondence in any number of languages. Alfonso replied in monosyllables and, when told of Maller’s praise, bowed in surprise, attributing it to a misunderstanding. Yet it must have been of him Maller spoke. Macario knew Alfonso’s home village and asked if he suffered from homesickness.

“A little,” replied Alfonso. He tried to complete the phrase with the expression on his face, and succeeded.

“You’ll get over it, you’ll see!” said Macario. “One becomes used to everything very easily, I think; to living in town after the country.”

Annetta did not find this conversation amusing and interrupted it without further ado. At the sound of her voice Alfonso raised his head, thinking that she wanted to ask him a question too, but was at once disappointed and so tried to hide the reason for gesture with the assumption of an air of close attention.

“D’you know, I’ve learnt some songs which are popular in Paris so as to act the Gavroche in the streets with Federico?”

Federico was Annetta’s brother. Miceni, who knew him, had described him to Alfonso as a very haughty man. He was in the consular service and was vice-consul at a French port.

“Could we hear one of these songs?” asked Macario.

“Why not?” and she got up. “Would you care to accompany me?” she said to Francesca. “Come on! Macario’s such a bore this evening that this is the best way of passing the time, I think.”

“That’s for us to judge, don’t you think?” replied Macario impertinently.

Alfonso forced a smile. The continual effort to appear at ease tired him. If he could have found a way, he would have left at once.

Francesca, sitting at the piano, had taken a bundle of music on her knees and was telling Annetta the titles. Annetta rejected each with a shake of the head, keeping a hand to her cheek as a sign of reflection. Finally she cried with a burst of laughter: “That one! That one!”

After a few introductory notes the Signorina started up a rudimentary but lively accompaniment.

Annetta began to sing in a sweet level voice, then to Alfonso’s great surprise she began to sway to the rhythm and pretend to run. Francesca roared with laughter; Macario laughed too, and even the singer could not contain herself, to the grave detriment of the song itself which broke off again and again. Then she became serious again, and so did Macario: Alfonso had only laughed in order to do as the others did.

As Annetta sang, she assumed various postures, pretended to be tired, crossed her arms over her breast as if to run better, avoided an obstacle which she cleverly mimed, asked pardon of a person she had bumped into as she ran.

Alfonso knew French, but he had a poor ear, so he found it difficult to understand. Macario, staring fixedly at Annetta and speaking in one phrase at a time in order to interrupt the song less often said:

“It’s a song sung … by a man … running after a bus,” he interrupted himself and murmured admiringly: “You’re doing it splendidly!”

Now Annetta really was tired; she was still pretending to run but jerking around less. She put a hand to her breast, and her voice broke into gasps.

“I can’t do any more,” she said and stopped.