11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

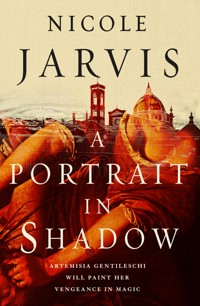

Enter a sumptuous world of art and magic in 17th-century Florence as Artemisia Gentileschi fights to make her mark as a painter and exact her revenge – perfect for fans of Alix E. Harrow, Elena Ferrante and Susanna Clarke. When Artemisia Gentileschi arrives in Florence seeking a haven for her art, she faces instant opposition from the powerful Accademia, self-proclaimed gatekeepers of Florence's magical art world. As artists create their masterpieces, they add layer upon layer of magics drawn from their own life essence, giving each work the power to heal – or to curse. The all-male Accademia jealously guards its power and has no place for an ambitious young woman arriving from Rome under a cloud of scandal. Haunted by the shadow of her harrowing past and fighting for every commission, Artemisia begins winning allies among luminaries such as Galileo Galilei, the influential Cristina de' Medici and the charming, wealthy Francesco Maria Maringhi. But not everyone in Florence wants to see Artemisia succeed, and when an incendiary preacher turns his ire from Galileo to the art world, Artemisia must choose between revenge and her dream of creating a legacy that will span the generations.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Nicole Jarvis and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Part I: June 19, 1614–September 18, 1615

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Part II: October 2, 1615–May 14, 1616

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

Part III: June 2–October 23, 1616

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Artemisia Gentileschi: The History

Reading Group Discussion Guide

About the Author

Also by Nicole Jarvis and available from Titan Books

The Lights of Prague

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

A Portrait In Shadow

Print edition ISBN: 9781803362342

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803363356

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: May 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Nicole Jarvis, 2023. All Rights Reserved.

Nicole Jarvis asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To all who are driven to create

“Quel, che l’anima e ’l corpo mi travaglia,è la temenza ch’a morir mi mena,che ’l foco mio non sia foco di paglia.”

“This thought burdens soul and bodyAnd makes me dread my death:Might my fire be only sparks and straw?”

—GASPARA STAMPA (1523–1554)Translated by Nicole Jarvis

PART I

JUNE 19, 1614–SEPTEMBER 18, 1615

1

Artemisia Gentileschi held her chalk so tightly it threatened to snap under the pressure.

The husband of her subject hovered over Artemisia’s shoulder while she sketched. She could feel his warm breath on the back of her neck when he leaned in to examine her work. A piece of red chalk crumbled beneath her thumb, smearing against the paper below.

The work promised to be one of her best designs yet. The Fenzetti had requested a sketched proposal for a painting of Europa and the bull, and she’d jumped to accept. She was still building her client base in Florence, and it was a subject she wanted to paint. The dark muscles of the bull contrasting with the vicious whites of its lustful eyes. Europa, hunched over its back and clinging for her life, staring down at the ocean washing over her knees. There was a sickly terror in every line, the threat obvious even to those who did not know the terrible end of the myth.

When they had arrived today, they had given the design a cursory glance before Signore Fenzetti requested that Europa’s face be altered to represent his wife. Reluctantly, Artemisia had pulled out cheap gray paper and her red chalk to make some sketches. She worked as well as she could with the pompous fool of a husband nattering by her head. Her ear was still learning the Tuscan dialect, making his chatter even more grating.

“We’ll also need you to include a certain necklace, a family heirloom. Wife, you know the one.”

“The pearls,” Signora Fenzetti said, heeding Artemisia’s earlier warnings and speaking without moving her mouth.

She sat on the stool against the wall of Artemisia’s small studio. Her face was round and pale, with wrinkles creasing the skin by her eyes and mouth. The early summer heat had dampened the small curls around her forehead. The rest of her silver-streaked hair was braided elaborately on top of her head, and her red gown tumbled to the floor like spilled blood. The Europa of the myth was a young woman, but portrait drawing always required the ability to imagine one’s subject as they might be in their most gracious daydreams, rather than how they were.

“They’ll make all the difference in the final painting. They’re expensive, so we didn’t want to bring them out until we’d met you.”

“Were you worried I was going to rob you?” Artemisia asked, sketching in the aquiline curve of the woman’s nose.

“It’s these streets. You’re not in the best part of town.”

That, at least, was accurate. The Fenzetti likely lived in the heart of Florence, along with most of the gentry. Artemisia, for affordability, lived across the river in Oltrarno, on a small side street off the Piazza Santo Spirito. Without central Florence’s broad, modern architecture dominating the narrow streets, her area was more crowded and unpredictable. She was not the only artist in the neighborhood, though the most popular painters would have more expensive studios across the city. Still, Artemisia had come to Florence with little, and this space was hers.

Signore Fenzetti had attempted to convince her to come to them so that he and his wife wouldn’t have to cross the bridge to meet her, but Artemisia had refused. She would not let Fenzetti believe he could control her entirely. She was an artist, one of the blessed and powerful—not a servant.

Signore Fenzetti leaned forward to peer at her sketch, and she tilted her shoulder to make it more difficult for him to see. “Is that how you plan to make her face look?” he asked.

“This is a sketch. I’m getting a feeling for your wife’s features. I’ll block it on the canvas before the first painting session so you can approve the design.”

“Yes, but does it need to be so shadowed? You can barely see her.”

“You saw how I paint,” she reminded him. He had been coy about even requesting the sketch until she had shown him a half-dozen paintings to prove she truly was an artist.

“I don’t understand this new style of painting as though everyone is sitting in a dark room,” he said. “Where’s the light? Where’s the clarity? That’s what art really is. Like San Raffaello. It’s healing magic—it should be pure and light.”

“The modern style is more realistic, signore,” Artemisia said, with a loose rein on her patience. “I want to show things how they are. When’s the last time you were in a room that was perfectly lit?” She gestured to the dramatic lighting of the studio around them. Away from the jagged edge of the sunlight coming through the window, there were corners of dusty darkness. “This is where art is going, and it’s my strength. I used to stare at Caravaggio’s work every Mass in Santa Mar—”

“Caravaggio?” the man scoffed. “That crazy painter who was killed in a drunken brawl a few years ago?”

Artemisia pursed her lips and took a moment to add a textured swirl to the sketch’s hair. “Artists die young,” she said, quoting her father. It was a phrase he’d used in all situations; whether he was happy or sad, celebrating or mourning, the refrain remained the same. He’d said it when they learned of Caravaggio’s death—her father had once been imprisoned with the man, and had respected his art, if not his personality. Caravaggio was a notorious bastard.

The phrase was not a simple platitude: art was a manifestation of the artist’s soul, and to drain one was to drain the other. The magics that flowed through the brush onto the canvas carried a piece of the artist’s essence, infusing the art with their very life. The ability to heal had a price, and artists who were not careful found an early grave.

“My friend Belladonna visited Rome a few years ago, and she said his paintings look dirty,” Signora Fenzetti commented, but closed her mouth when Artemisia frowned at her.

“Life is dirty. You’ve seen my art,” Artemisia said. “I’ll make some small adjustments for your preferences, but my style is my style. You chose me. Let me do what I do best.”

Signore Fenzetti huffed but didn’t push back.

Artemisia rarely included representations of her clients in her paintings at all. Her art was her passion, her legacy, and following the vain whims of an aristocratic patron was against everything she strained to be. But she needed money to keep painting at all. And keep a roof over her head.

A small voice in her head with the gruff cadence of her father reminded her that if she’d married as he’d wanted, she wouldn’t need to worry about supporting her lifestyle on her own. She pushed the thought away, locking it back with all the other itching, nagging regrets from her time before Florence.

Better to be beholden to a patron for one painting than tied to a husband for the rest of her life.

“Should this work be tied to one of you, or open for all? That will impact my approach from the beginning. I imbue my magics from the first brushstroke, and that energy must remain consistent for the months of work.”

If the art was meant to heal one person only, she could layer in their hair or blood at any stage of the painting, but the magics she pressed through her brush had to be deliberate from the start. Without the personal targeting, the painting would lose power every time a stranger passed the canvas.

An exchange of material was a contract of trust on both ends. The artist had to trust the client would pay them for their drained life force. The client had to trust that the magics the artist was weaving into the canvas were for good, rather than ill. It was only a matter of intent that separated healing from necrotic magics.

Fenzetti huffed. “We’re not paying to heal everyone who walks through our house. It should be tied to only the two of us.”

“That’s not possible. It can be tied to one person, or none at all. You’ll need to pick.”

“Fine. Then you’ll need my wife’s hair. It’s, ah, for fertility,” Signore Fenzetti said.

And they had chosen the rape of Europa? Fenzetti had likely seen a depiction of the myth in the house of some man he respected and not thought twice about the story. The painting didn’t need the symbolism in the design to work, no matter what superstition said. It only took the artist’s will—and their life force. Still, there was normally some thought behind it. Perhaps thinking was not Signore Fenzetti’s strength.

“The painting will take me a year to complete, at least,” she told them. “Art is a long process, both by necessity and design. Fresco artists work far more quickly than those of us who use oils, but longer timeframes collect more magics. I’ll target all of the magics toward making her womb catch, if that’s your only concern. With luck on your side, she’ll be with child soon after I deliver the painting.”

“Luck? I’m done relying on just luck. We have been married for more than ten years, and I’ve yet to get an heir. This painting needs to… fix her.”

On the stool, Signora Fenzetti flushed. She kept her eyes on the point across the room Artemisia had told her to stare at, but her hands twisted on her lap.

Artemisia hummed. “You’re sure she’s the one who needs fixed? Art can’t change something that isn’t broken. Making an heir does take two.”

“No seed has taken root, but that doesn’t mean the problem is with the tree,” Signore Fenzetti snapped.

“Gregorio,” Signora Fenzetti exclaimed, mouth dropping open. She lost her pose, turning to look at them. “This conversation is inappropriate. She’s a lady.”

“I’m no lady,” Artemisia demurred.

“She has to understand if she’s going to fix you,” Signore Fenzetti argued. He gestured at Artemisia without looking at her. “Besides, we know it’s not too delicate for her ears.”

Artemisia’s charcoal stilled mid-stroke. “Pardon me?”

Signore Fenzetti turned back to her. His chest was puffed, defending his bruised ego like a bird distracting a predator away from its nest. “You didn’t think that we would do our research on you before we hired you? We asked around about you, heard about that disgusting business back in Rome.”

It was as though Artemisia’s veins filled with river water, thin and cold and rushing. She’d only been in Florence for three months, and her past was already haunting her. Would this shadow follow her everywhere?

“We weren’t going to mention it,” Signora Fenzetti said, giving up any pretense of modeling for her. She gave her husband a meaningful look, though he didn’t seem to notice. Artemisia had the feeling that this man ignored most of what his wife said. “We just wanted to be sure you were really an artist. There are too many cons in this country. The reports said that despite the drama, you were as good as you claimed.”

“Of course,” Artemisia said faintly. She wasn’t sure they would hear her. Her lips were numb. Her whole body was numb.

“Besides, all good artists have a whiff of scandal about them. It’s part of the charm.” She gave Artemisia a simple, earnest smile.

Charm. As though what had happened to Artemisia was a game she had played for their amusement.

She closed her eyes for a moment, reaching up to tightly grasp the amulet at her throat, and then said, “Get out.”

“What? You haven’t finished the sketch yet! We’ve barely been here a half-hour,” Signore Fenzetti blustered.

“You can come back when you can keep your opinions to yourselves,” she said, putting down the paper and standing up.

“I told you we should have gone with Paolo Lamberti,” Signora Fenzetti said.

“A painting from the new woman artist… It would have been interesting,” her husband said. He snatched up the original pen-and-ink design and began rolling it up briskly. “Ah well. He can finish this.”

“Wait,” Artemisia said, holding up a hand. “You can’t take that.”

“We commissioned it,” he said, tucking it tightly under his arm. “These first sketches are a test, which you’ve clearly failed. The temper on you.” He shook his head. “A full painting is an ambitious task. You should be proud we’re impressed enough with your design to keep it.”

“My design is flawless,” Artemisia told him, hands trembling. “Who is this Paolo Lamberti?”

“He’s from the Accademia delle Arti della Magica. He’ll do the design justice.”

“How could he? It’s not his art. That’s my design.”

“Which we paid for,” he said. He reached into his purse and then held out three giuli, eyebrows raised.

“This was not what we agreed to,” Artemisia said, though she did not refuse the money. It was a pittance beside what she would have made for the full painting, but she could not spurn it.

As she took the coins, she dragged the tips of her fingers against the man’s hand. Around her neck, her amulet pulsed. Signore Fenzetti winced and stepped backward. She bared her teeth at him in a vicious smile and closed her fist around the payment.

“You’ll regret this,” she said. “When every man of importance in Florence has an Artemisia Gentileschi painting in his gallery, you’ll regret this day.”

Signore Fenzetti shook out his hand and ushered his wife toward the door. Artemisia’s face burned and a sting behind her eyes threatened to rip away the last of her dignity.

“One more thing,” Signore Fenzetti said, pausing at the threshold. “You should find a husband sooner rather than later. With a better manager, perhaps issues like this could be avoided.”

With that, her temper finally erupted. “Out!” Artemisia shouted.

The Fenzetti left. She slammed the door behind them and pressed her forehead against the wood. Through it, she could hear Signore Fenzetti loudly complaining about the fickle nature of women before their footsteps finally retreated down the stairs. She let out a shaky breath and then swore quietly.

Her hand ached from holding the chalk even for that short time. She flexed it, and then dug her nails into her palm.

* * *

Once she put away her supplies, Artemisia locked up her studio and left. If she had to sit still in her quiet studio, her nerves would boil over. Her work could distract her, but painting required energy, focus, and passion in order to transfer its magics, and right now all she could muster was bitterness. There would be no healing from her hands today.

Her design. Her design. And those stronzi were handing it to a stranger, just because he had the Accademia backing him.

The Accademia delle Arti della Magica—The Academy of the Art of Magics—was the heart of Florence’s artistic community. The Accademia collected the best artists in the city for classes, ceremonies, and legislation. Standing apart from and above the guilds of simple craftsmen, the Accademia studied the most hallowed work: art. Members of the Accademia combined the exploration of magics with the perfection of technical artistic mastery.

Still, what man could take her design and do it justice? What man could capture Europa’s feelings about being taken into the ocean on the bull’s back, her rape or death imminent?

She needed commissions if she was going to be able to afford her rent and food—and her paints and canvas. Some days, she felt the latter were more vital than the former. She was not simply an artist for the money. With her youth and circumstances, there was certainly other, more reliable work to be found.

But she was no one without her art.

Even so, it was often thankless work. When she was not busy with the few paintings she was being paid for, mostly for foreign buyers unaware of her recent infamy, she spent her time on her designs to impress potential new patrons. Her commissions from abroad were not an infinite resource—she needed local patrons, people who would see and support her regularly. Even though she didn’t infuse her sketches with magics, they were a drain on her mind, her eyes, and her hands. She was flinging her energy into a void that pulled everything away and left her with no trace. Art did not love her back, and certainly neither did the attached politics. Her smiles were worth nothing, and one harsh word had destroyed the chance of a well-paying commission.

Her art was good enough. She was talented. There were untapped wells inside her waiting for the right commission to show themselves.

If she could not find more patrons, that would not matter.

* * *

Though she had not been in the city long, Artemisia had quickly learned the shortest path to the river. In Rome, the Tiber had been her constant companion. In comparison, the Arno was unfamiliar, at least thirty meters narrower than the slow, vast water she knew back home. Still, the sound and stink were the same in any city, and were a comfort when nothing else felt familiar.

Ponte Vecchio, the city’s central bridge, was crowded chaos. The early summer heat had drawn people from their homes like fish to bait. She crossed it without considering any of the stalls of food and trinkets, ignoring the calls of vendors and the arguments of shoppers. Someone collided with her in the walkway and exclaimed in surprised pain. Artemisia grabbed her amulet, ducked her head, and pressed forward. Quick, angry words followed her, but the dialect was too thick and unfamiliar to understand.

Florence had more than double the population of Rome, all centered around the river. The crowds made Artemisia’s pulse race, tripping and stumbling inside her ribcage. Too many eyes were on her in the press of people.

Judging. Whispering. Watching for any sign of weakness. Wanting to hurt her, to twist and torment her until she broke under their hands.

She turned right off the bridge, following an arched walkway along the water. She was moving too quickly, bumping into people as she fought free of the crushing crowd. The archway only lasted a few dozen yards before opening into a broad sidewalk along the water. The crowds thinned immediately, and Artemisia slowed.

She slumped against the barrier by the river. The stone was cool and firm. No matter how heavily she leaned on it, it stood steady. She took a deep, deliberate breath. The air, like all city air, was heavy with the scents of humanity, but there was a breeze over the Arno that brought a hint of freshness.

She could not be so sensitive and stubborn unless she wanted to lose all her clients. If she did not choose her compromises, they would choose her. Art would never be solely about her passion. She needed patrons to buy her work. That meant diplomacy. So, the rumors had followed her. She had known they would. She still had to press forward.

Her internal scolding did not work. Panic continued to churn inside her. She could not make her past feel small, no matter how she tried to smother it.

Was there a way to succeed single, alone, and penniless, with her reputation haunting her every step? Her talent was her only advantage, and none would see it if she were turned away at the door. She had no validation in Florence, and the Accademia would not look twice at a female artist.

After all her fighting, she could still lose everything.

The buildings back on the Oltrarno side of the river sat flush against the water, their façades soft shades of yellow, white, pink, and tan. The narrow buildings crowded together and peered over the river’s shallow water like tourists over a bin of cheap jewelry.

The river trudged along far below, as though fighting against the silt beneath it to move forward.

* * *

After Artemisia returned to her studio, she clenched her teeth and set to work again. Even without commissions, there were things to do. Beyond its ability to heal, painting was a craft—one that needed constant practice to hone, and much work beyond putting a brush to canvas. She pulled out her sketchpad to design potential new painting layouts, trying to push the tension of the morning behind her.

The page was still blank when there was a hard knock on the door.

Her landlord stood outside, his face ruddy beneath an unkempt gray beard. Valerio Gori was an older man, but rather than becoming frail, his bulk had settled over time. It had taken much convincing for him to allow her to have her studio in his building. He was traditional, and the idea of an unmarried female artist living under his roof had made him uncomfortable. After she’d shown him her work and assured him that she would cause no trouble, he had reluctantly relented.

“Your clients left quickly,” he commented. He lived in the apartment on the ground floor and kept a griffon’s eye on the comings and goings through the front door. For the first week, Artemisia had found it comforting. Now, she felt scrutinized.

“They did,” Artemisia said, not moving to let him inside the studio.

“I let you rent this place because you assured me that you had money coming. I’m beginning to doubt that.”

“I paid my rent.”

“For this month,” Gori said. “And you were late.”

She had lost her old patrons even before she had left Rome, along with most of the friends and family who could have made new connections. She had been certain her talent would speak for itself, and she would find a new audience more quickly in Florence. She had been wrong. “I’ll have the money next month, too.”

“It’s bad for my business to have an unmarried woman living here. People will talk,” he said.

“I’m an artist. My eccentricities are charming.”

“Is that what people tell you?” he grumbled. “Stop scaring off your clients. Artistic fits of passion have no place here if you want to keep this roof over your head.”

She swallowed a snarl, and its claws and teeth shredded her throat on the way down. “Of course, signore.”

He examined her like a farmer considering if a sheep were ready for slaughter.

“I should get back to work,” she said.

“You should,” he said, as though it were his idea, and clomped back down the stairs. Her hands shook as she closed the door behind him.

* * *

That night, she paced her studio, running her hands through her curls and tugging at the ends.

Gori was searching for an excuse to evict her and fill the studio with a married couple with a steady income. He had no sympathy for her plight.

What would she do if she failed to support herself in Florence? She would not return to Rome, and she did not want to marry. But was death preferable to those options? If she were forced out of this studio, already small and barely affordable, she would end up on the streets.

She had survived terrible things in Rome, things she had thought would be unbearable, but homelessness in a foreign city could finally end her.

Nothing she did was enough.

If she did not act quickly, the world would not remember Artemisia Gentileschi. Her career was slipping from her reach.

She refused to die without leaving a legacy. The patrons of the world could ignore her all they wished, her fellow artists could condemn her—but her art had a power of its own. Power most artists were too afraid to use.

There was a piece she had tried before but had been too raw to complete. Magics took passion, but also restraint. One had to hold onto an emotion for years to fully weave it into art. A flood did not water a season’s crop; it drowned it. Too much or not enough could ruin the magics. Perhaps now she had the distance needed. This would be a true test of her power.

She had tools with which to fight, even abandoned on her own. She could get her vengeance and make the world remember her with one painting.

Artemisia had nothing left to fear.

The night outside her studio window was quiet except for the early summer winds dancing over the city. The bells had stopped tolling, allowing the citizens to sleep during the darkest hours.

There were three mirrors in her studio and drapes she could pull over her windows when she needed to see beneath her clothing. She set one mirror against an easel so she could look into it to begin her sketch. She had to find the perfect design for this piece. Nothing less than transcendence would give her the power she would need. She needed to take the time to get it perfect now—she would start infusing the magics when she put oil to canvas, so could not afford to change her plan then.

She watched her face contort, and then freeze in place. Her charcoal moved quickly, trying to capture the emotion before it faded to rigor.

Effort. Determination. Disgust. Mercilessness.

With the candle flickering beside her, her face seemed demonic in the reflection. The shadows were dynamic, like one of her own paintings brought to life.

Her charcoal cracked as she colored in half her face in solid black.

2

When she opened her door to find a messenger boy waiting outside, Artemisia sighed. Once, she had looked forward to the appearance of letters. Most of her commissions had been established by mail. Since her move to Florence, though, it had been a humiliating experience of handing over her dwindling money for a flowery rejection from uninterested patrons.

She gave the boy a coin and closed the door behind him. She leaned against the wooden frame, rubbing her eyes with charcoal-stained hands. After the Fenzetti had left her without a commission in her queue, Artemisia had fallen deeply into the sketch of her new idea, working late into the night. It had created a fire in her belly that burned bright when the world was dark and still, but just the drafting, wrought with emotion even without the need to weave magics into the sketch, was exhausting. When she put brush to canvas, the energy would be harder to find. If she went through with it, this piece would drain her more than anything she had ever done. And yet, as she sketched, she felt a closed door finally start to open before her. It was only a thought for now, an option, but it gave her a sense of purpose she had lacked for months.

Still, her hands were clumsy with exhaustion as she flipped over the letter.

The scarlet wax seal displayed a crest with a crowned shield, featuring six balls in flight. It was a familiar symbol, one found both in Florence and Rome on the cities’ most important buildings.

Carefully, not breathing, she broke the wax and unfurled the letter. She clumsily mouthed along with the Tuscan dialect once, and then twice. By the time she understood the message, she could barely believe what it said.

Perhaps she had a chance in Florence after all.

* * *

Though Artemisia lived across the river from most of Florence’s landmark buildings, such as the famous Duomo, she was only a three-minute walk from the sprawling Palazzo Pitti. The vast palace stood like a barricade to the west, so solid and imposing it might have been another city wall. Unlike its predecessor, the towering Palazzo Vecchio on the other side of the river, the Palazzo Pitti was a heavy, low building with a uniform, rustic stone façade. It seemed to stretch endlessly in either direction.

Artemisia stopped in front of the heavy man standing guard at the entrance, bathed in the golden light of dusk. He wore the Medici livery poorly. He was too large, too strong, to carry the embroidered velvet with any grace. A bear in a jester’s costume. She stayed a few steps back. She’d spent too much time with hulking brutes who used their authority to manhandle people to put herself in easy arm’s reach.

He looked her over. She expected him to turn up his nose at her dress. Though it was the best one she owned, it was only a sturdy, practical wool instead of the velvets and silks that this building’s usual visitors likely wore, and would betray her as out of place. However, he simply said, “Invitation?”

She held out the scroll, which he studied carefully. Artemisia wondered if her thumb rubbing over the signatures at the bottom so often since its arrival had faded them. In the last week, she had checked the date and time on the letter often, fearful she might have misread it and lost her chance. After the guard checked the seal, he stepped aside to let her through the door.

As soon as Artemisia stepped inside, the Palazzo Pitti transformed from an impenetrable wall into a breathtaking masterpiece. The ceilings arched high overhead, ending in ornate, pastel frescoes framed by intricate gilding. Everything was decorated with gold and rich, dark wood. Even the simplest walls were accented with filigree and carvings in relief near the ceiling. The Medici’s six-ball crest hung on the wall to the left of the entrance.

The Medici family had purchased the palace from its original owner—the eponymous Pitti—and transformed it into their own, filling its empty halls with the most powerful art in Florence. As the most influential family in the region for the last several generations, they had the money to make their home rival even the biggest churches. Over the years, the Medici’s economic grip on Florence had grown into a political one, and their influence had spread like roots throughout Europe, including putting one descendant in the Vatican as Pope and another in France as Queen.

Artemisia had been searching for a client powerful enough to launch her career in Florence, and was now in the home of the most powerful family in Europe.

Another liveried servant cleared his throat, pulling her attention from a closer examination of the walls. He bowed and gestured for her to follow him. They skirted a massive inner gallery hall filled with marble statues, both free-standing and tucked into alcoves. Though the influence of artwork not tied to a specific client would spill out to reach everyone in the area, there were patches of rubbed white on their bases where passersby had attempted to draw upon the energy inside directly. Either the statues were long-since run dry, or the Medici were unusually generous.

The next hall was filled with paintings, and her eyes caught on a piece featured in the center of the room on a pedestal. A soft hand had painted a delicate Virgin and Child. Though framed with black shadows, this was no Caravaggio. It was gentle and clean, with skin so supple that it could have been by Titian if not for Mary’s slenderness.

“That is gorgeous,” Artemisia blurted. She paused on the threshold of the hall, though her approach was blocked by a velvet rope. This answered the question of the statues—she was sure there was not a drop of magic to be found in that gallery. Here, there were likely still paintings with magics inside. They were displayed just out of reach of their guests, reminding them of the Medici’s power without sacrificing the well of magic. “Who is the painter?”

The servant glanced back at the piece which had caught her attention. “San Raffaello,” he said, and the breath caught in her throat at the mention of the saint. “This way, signorina.”

He led her up a grand stairwell and down a hallway. From a window, she could see a vast garden behind the palace, lit in rich golds by the setting sun. It was so manicured that she might have thought the window a painting if the lush smell had not drifted in.

Voices came from the door at the end of the hall, quiet murmuring punctured by laughter. The servant opened the door for her, and then left her to fend for herself. Unsurprisingly, this room was as decadent as the rest. Tall bookshelves lined the walls, each stacked with ornately bound texts all the way to the ceiling, which boasted an intricate fresco of the Roman gods at ease.

The other guests were packed around the room in small clusters, talking to each other over glasses of wine. It was a more diverse crowd than she had expected—there were as many practical trousers as there were velvet doublets.

Artemisia scanned the dense crowd, looking for an entrance. Her father’s approach to making contacts had been to get uproariously drunk and make friends with every person in the room. Though he had a vile temper, he was never without a crowd of companions, all of whom saw Orazio Gentileschi as a bosom buddy. Many Romans had used the Gentileschi’s small flat as a meeting space, flitting in and out as if they’d paid rent. Some had been friendly, others had pursued Artemisia with unwelcome drunken advances, and all were fickle—few had stood by the Gentileschi family during the trial.

In a room like this, Orazio would have either found the man who looked like the most fun—or the wealthiest. Growing up, Artemisia had always been comfortable in crowds… until the day they had turned against her. Now, she felt as surrounded and overwhelmed as she did on the local market’s busiest days. There were so many people here, so many strangers. She didn’t recognize anyone, but that didn’t mean no one would recognize her. As the Fenzetti had demonstrated, the gossip from Rome was seeping through the city walls.

“Artemisia!”

She jumped, but her shoulders slumped with relief when she recognized the older man approaching her. “Signore da Empoli,” she said. “It’s good to see you.”

“Call me Jacopo, Artemisia. You’re no longer a little girl. You’ve truly grown!” he said, kissing her on both cheeks. Once the pleasantry was finished, Artemisia stepped back so she had room to breathe. She’d left her amulet at home so she would not risk revealing it to the Medici, but she felt exposed without it. “I’m glad you could make it. I’ve been keeping an eye on the door all night!”

“I presume you are the one to thank for this gracious invitation,” Artemisia said. She had sent Jacopo a letter when she arrived in Florence to request introductions to any patrons he thought would appreciate her work—especially someone from the Medici family. He, like all the other old family friends she had tried, had never responded, and she had assumed he had used the letter for scrap paper.

“I told the Grand Duchess they would regret not inviting you!” he said. “Your work rivaled your father’s even years ago, and you’ve only grown. If they claim to be patrons of the arts, they can’t allow Artemisia Gentileschi to roam their city without having her to one of their dinners! I told them all about you, and Madama Cristina had an invitation drafted immediately.” Catching her expression, his smile faltered. “Not all about you, of course. I imagine you’re looking for less talk of all that here.”

“Indeed,” Artemisia said faintly.

“I thought Aurelio might have put in a word for you, too. He comes through Florence often enough.”

Aurelio Lomi was her father’s half-brother, a fellow artist. He was successful in his own right and had supported both Artemisia and her father in their careers. He had always had an easier smile than her father. Even when he had clashed with Orazio’s strong personality, he had been kind to Artemisia. When Artemisia had refused to marry before arriving in Florence, her connection to her uncle had dried like a well in summer. All letters requesting aid or advice had gone unanswered.

“I haven’t seen him,” she said. “How often do you dine with the Medici? Are there always so many people?”

“Usually more! You know the Florentines—plenty will slip in halfway through the meal, kissing cheeks and pretending not to know the time.”

“Who are they? Are they all other artists?” She’d known the scene in Florence was competitive, but nothing like this. Was everyone here tonight vying to have the Grand Duke as their patron? It was little wonder so few patrons had answered her letters.

“Heavens, no,” Jacopo laughed. “We’d be in real trouble then. No, the Medici have diverse interests. There are some other artists here too, of course. A few other painters, some sculptors. Most of the Accademia has some tie with the Medici.” Jacopo was a member of the Accademia, just like the man the Fenzetti had given her design to. The organization was key to most artists’ success in Florence. “The duchess Madama Cristina is currently favoring a weaver from the north who is said to be able to create tapestries so perfect they could be mistaken for paintings. Said, I suppose, by people with poor taste in paintings.” Though the duchess’s son, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, ruled the region, the older woman was renowned as both politician and patron.

Artemisia had met a handful of weavers in Rome, but they were rarer than painters. Their medium took more space, and though large teams worked on mundane tapestries, magical weavers were forced to work alone. Magics gained power from consistency and dedication, pooling in a piece of art over the months or years it took to complete. It was a delicate balance to maintain steady energy and passion for so long and would have been impossible with a partner.

“The rest are from a range of fields. Politicians, to be sure. Leaders from the local guilds who are either looking for Medici favor or have control over something the Medici want. They invite philosophers regularly. I think the duchess likes to hear them argue, to be honest. And don’t forget the other patrons in Florence. Wealthy people attract each other like drunks. They’re always interested in someone who can get them more of what they already have.”

Artemisia rolled her eyes. “Fun company.”

“Don’t be so cynical,” Jacopo said, smiling. “Patrons are what make an artist’s world turn, when the Church is being stingy. Your father told me that you’re doing well. What pieces have you been working on?”

She was not surprised to hear her father had exaggerated her successes to his old friend. Artemisia’s fall from grace was shameful enough without admitting he had written off responsibility for her when she had refused to marry or join a convent.

“Is this her?” The woman who interrupted them was dressed in full mourning, wearing a black gown and a widow’s cap over her hair. In contrast to the severe cloth, her face was unexpectedly plain. Her chin was small, and her eyes were the warm brown of the earth by the Arno.

“It is,” Jacopo said. “Artemisia Gentileschi, meet the Grand Duchess Cristina de’ Medici.”

Artemisia’s breath caught. “Your Grace,” she said, and curtsied a beat too late.

“You may call me Madama Cristina. You’re our guest here. I’m so pleased you could come,” the duchess said. “As soon as Signore da Empoli told me a story about the young painter in Rome who could paint so beautifully that her father’s own friends couldn’t determine which pieces had been done by her and which by him, I knew I had to meet you.”

“You flatter me,” Artemisia said. A flush warmed her cheeks.

“You’re younger than I expected, and so beautiful. How old are you?”

“Nearly twenty, signora.”

“So much time ahead of you, and already the stories of your talent are spreading! I’m pleased you’ve come to Florence. All the best artists do.” Artemisia smiled, though that was no longer as true as it had been during the era of San Sandro. Art had moved to Rome, closer to the heart of the Church, and Florence was on the decline. “Your father, he must have been disappointed not to have sons. It worked in your favor.”

“I do have brothers,” Artemisia said. “None of them showed any artistic talent.”

“My goodness,” Madama Cristina said. “He chose you over them? Your art must truly be special. You must show me your work sometime.”

Artemisia smiled at her, finally recovering her wits. “I would love to. It would be an honor to create a painting for the house of Medici.”

“We shall have to arrange it. But why don’t you have any wine yet?” She lifted a hand, and a liveried servant bearing a heavy silver tray appeared. She took a crystal goblet and handed it to Artemisia. “We take care of our guests.”

“I’m grateful to be one,” Artemisia said, accepting the wine. It was rich and sweet, framed by notes of cherry and oak.

An attendant rang a bell by the door. “Thank you, everyone, for joining the esteemed Grand Duke and his family tonight,” he called. “Dinner will be served shortly. Let us proceed to the dining room.”

As one, the mob ebbed into the adjoining room.

“Perfect timing,” Madama Cristina said, giving Artemisia a quick smile. “I heard some academics complaining of their empty stomachs when they thought I could not hear. I was worried they might start upon the wall furnishings.”

Each setting at the long wooden table was marked with a small slip of paper bearing the name of a guest. Jacopo helped Artemisia find her place but was swept further along the table before he found his own. He was near the far end, by the Grand Duke’s family. Artemisia sighed and took her seat alone.

Though there was no food set out yet, the table was nearly its own form of art. Large floral arrangements accented with fresh fruit or pheasant feathers decorated the surface every few feet. The silverware was polished to a shine and was heavy in Artemisia’s hand. She examined a fork closely. There was an intricate engraving on the handle of a griffon in flight.

“Is there something so interesting on the cutlery,” asked an amused voice beside her, “or are you simply imagining the food that will adorn it?”

Artemisia turned to the man who had taken the seat beside her. He was close to her age, youthful and vibrant compared to the table’s elder guests. His dark hair was pushed away from a sharp and angular face. The embroidered cloth of his tunic could have come from one of the Medici’s elaborate wall tapestries.

“Are you so blind to the beauty around you that you didn’t even notice when it’s in front of you?” she challenged.

“I’ve been here before,” he said with a shrug. His accent was smooth and cultured, slipping through the syllables like water down a stream. He gave her a considering glance, and then added, “And I’ve seen silverware before, as well.”

Before Artemisia could retort that she’d seen silverware before, the servants arrived with the first course. The broad dishes they set in the center of the table were covered with an assortment of fresh crostini, spiraling by color across the platter: black olives mixed with bright green herbs; lush pieces of fresh fig piled on pale goat cheese; green capers and a dark smear of liver. Another set of servants came by to refill everyone’s wine, leaving pitchers on the table for easy access. The delicate glasses were wide and nearly as flat as the plates, making them difficult to drink from.

Artemisia plucked two of each crostino off the platter and moved them to her plate. She had only had some bread as her lunch, and the wine threatened to untether her head. Her mouth watered at the promise of a rich meal—she had lived so long on crumbs that she forgot how it felt to be satisfied.

“All that fuss about the forks and you can’t even use them for the first course,” the man beside her said. His voice was solemn, but his eyes were bright.

He was right—everyone else at the table was crunching into the crostini using their fingers. “I’m sure I’ll get the chance,” she said, and took a bite of the liver crostino in as defiant a manner as she could. The salty musk of the liver tasted how velvet felt, and the burst of a caper between her teeth gave the mouthful a sharp echo. The complexity cut through the heaviness of the red wine, and she took another bite quickly.

“I don’t believe I’ve seen you here before,” the man continued.

“My obsession with the silverware didn’t give me away?”

“That was my attempt at asking for an introduction,” he said. “I’m Francesco Maria Maringhi.”

“Artemisia Gentileschi.”

He glanced down at her unadorned hands. “Is your father an associate of the Medici?”

“No,” she said. “He lives in Rome. I’m here at the Grand Duchess’s invitation. I’m a painter.”

Unfazed by her coolness, Maringhi’s expression brightened. It wasn’t until she had his full interest that she realized how idly he had been speaking. It was like being engrossed in a puppet show, only for the puppeteer to step from behind the curtain. “That’s unexpected,” he said. “I don’t believe I’ve ever heard of a female painter.”

“You have now.” She turned back to her plate, and he stopped attempting to draw her into conversation. Instead, he turned to the old man on his other side and began talking briskly about a shipment of stone from Pisa that had gotten stuck in a riverbank thanks to the low water levels in the Arno.

Artemisia glanced to her left, but the woman next to her was fully engaged with the man beside her. From the way she touched his arm, she was likely a wife or a mistress.

Artemisia ate another crostino. The figs were sweet and fresh, but the taste was dampened by her unease, like a cloud covering the sun.

Another course of antipasti arrived—fresh oysters in their half-shells were scattered with lemon slices on new platters. Artemisia took one, almost reverent. They were far from the sea in Florence, and transporting so many oysters for a dinner party must have been expensive. On the coasts, oysters were as common as bread, but they were a luxury here—Artemisia hadn’t had one since she’d arrived in Florence.

Inflamed voices drew her attention before she could eat. In her youth, raised voices had been natural. Her father’s friends were passionate, aggressive men, and had enjoyed arguing more than agreeing. Now, her spine tensed.

Across the table, a middle-aged man was drawing attention. His clothes were as luxurious as those around him, yet his graying beard was untamed, as though he hadn’t given it a second thought before coming to dinner at the Palazzo Pitti. He was in a heated discussion with the men seated beside him while those around them watched with interest.

“Yes, we know how you feel. Your letter has been making the rounds,” commented the man on his right.

“There’s no need to read my private letters when I’ve published several books on the topic. I’ve made no secret of my astronomical inquiries. I am, in fact, the court mathematician. It is my job to try to understand the universe, and my duty to share those findings with the world.”

“You truly believe that you and your telescopes can tell us more about the world than we can learn from the Bible?” demanded the man on his left. He had a florid face and thin, white hair.

The man in the center shrugged. “I’ve heard it said: the Bible is a book about how one goes to Heaven—not how Heaven goes. You must admit that as a teaching tool, the Bible is ineffective. God gave us our intellect in order for us to use it, to understand this universe he created. If the Bible was trying to teach people astronomy, you would think it wouldn’t have skipped over the subject so completely.”

“Perhaps the problem is with your interpretation,” the other man said. The crowd rippled with hissed whispers. It was a damning comment. Since the Reformation troubles in the north, the Church had become even more determined for Catholics to leave the understanding of the Bible to the Vatican.

“Or perhaps it lies with yours. You!” The man pointed at Artemisia, obviously noticing her interest. “You’re a simple girl, yes?”

Artemisia felt her face flush with the awareness of many eyes on her now. Her hands shook in her lap. She took a steeling breath and raised her eyebrows. “That’s not how I would describe myself.” Her Roman accent seemed harsh to her own ears, her consonants loud and blunt.

He waved away her defense. “I meant that you’re not a scholar of astronomy or mathematics. Is that fair to say?”

“Yes,” she admitted.

“If you saw evidence with your own eyes of something where someone had once told you there would be nothing, would you believe that you too had seen nothing?”

“No, not if I had seen something,” Artemisia said.

“Even if the someone who had told you that there would be nothing was very respected? Perhaps even someone you personally idolized?”

“No,” Artemisia said, voice growing cold. “I trust my own eyes, and my own experience. I don’t allow others to shape what I believe.”

The florid man interrupted. “This is distracting from the point. You’re trying to contradict the Scripture.”

“If your faith in the Scripture can be shaken by learning more about our universe, then your faith is weak indeed,” the man said. “I’m uncovering secrets God left for us. There’s nothing for me to discover that He did not create. Wouldn’t you agree?”

The man floundered. “Well… Of course, I…”

There were chuckles from those around the table who were sympathetic to this scholar, and scowls from those on the opposing side.

“We’re all simply attempting to appreciate God’s work,” the man continued. “It’s unfortunate for you that you do not have the capacity to grasp its grandeur.”

An impromptu round of applause came from the scholar’s supporters, drawing the attention of the rest of the table. From their expressions, arguments were a common occurrence at Medici dinners. The loser of the debate, now so flushed he was nearly purple, spluttered for a moment before letting himself be pulled into another conversation with his seatmate.

Seeing the debate was over, those around them went back to their own conversations. The scholar leaned forward to speak to Artemisia more quietly, eyes still bright with triumph. “I hope you were not alarmed by my including you in our discussion,” he said. “Sometimes it helps to have a voice of innocence, rather than indulging the biases of both sides.”

She waved a hand. Now that everyone’s attention was gone, she felt lighter. “I was raised with artists. I like my conversation with a bit of antiestablishment sentiment. Propriety is for people with nothing of importance to talk about.”

“Artists, hm?” he asked. “I see you followed in their footsteps.”

She raised her eyebrows, and he nodded to her hands. She realized now that there was still a streak of yellow paint on the underside of her right hand, where she had rested it against her palette in thought. She covered it with her left.

Beside her, Maringhi huffed quietly, a small, amused sound that told her he’d been following the conversation closely.

She didn’t give him the benefit of her glance. Instead, she focused on the older man across the table. “I did.”

“I like artists,” he said. “They’re innovators. They try to find the truth in the world and reflect it on canvas. Anatomy, geography—did you know that San Sandro’s Primavera shows five hundred species of plants? But it doesn’t look like a botanical study. It’s beautiful.”

“You’ve seen it?” Artemisia asked. San Sandro Botticelli had at least one painting in Rome, but it was woven with such powerful magics it was still reserved for the Pope and his cardinals a century after the artist’s death. The Vatican was a treasure chest of the world’s most powerful art, holy work for holy men, and it kept the religious leaders alive far longer than the average man. Primavera was one of San Sandro’s works commissioned by the Medici, hidden away from the public eye.

He nodded. “It’s here in the palace.” He glanced down the table, as though making sure the Grand Duke was out of earshot. “It was a fertility commission, you know. All the magic is gone now, so they see no harm in showing it off to certain visitors. They like to brag that it was the magics that made a certain son born the year after its completion reach the success he found.” He raised his eyebrows and put a finger to the side of his nose. “Pope Leo the Fourth.”

“If a painting could make someone the pope, artists would be living in palaces,” Maringhi commented, lazily plucking another oyster from the platter in front of them.

“I doubt it. Holding the power to extend someone’s life hasn’t even achieved that,” Artemisia pointed out. “But it doesn’t matter. Even San Raffaello could not have painted a child into the papacy. Our magics can bring health, not success. There’s only so much that we can control.”

“But it’s a good story, isn’t it? San Sandro certainly never bothered to deny it,” the scholar said.

“He should have. He was a saint. He was good enough not to need the lies. He should have been honest. I had a client last week half-convinced I was trying to scam him,” Artemisia said. “There’s so much false information out there, clients either expect more than we can promise, or assume it’s all a swindle.”

“From what I’ve seen, most artists like a bit of mystery to their craft,” the scholar pointed out.

“Liars like to have something to mask their actions,” Artemisia said. “I don’t think the truth should be hidden in the shadows for anyone’s benefit.”

“Well said. I never had the chance to introduce myself,” he said. “I’m Galileo Galilei.”

“Artemisia Gentileschi.” She hesitated, the lilting rhythm of his name stirring something in her memory. “I’ve heard of you. My father didn’t pay attention to news outside our circle, but some of his friends did. I’m sorry—I don’t remember any details.”

“I prefer it that way. Rumors have not always been kind to me.”

“I understand that. We shall have to decide our own impressions, then.”

The next course arrived. Steaming bowls of pappardelle topped with meat sauce replaced the trays of oysters. Before she could reach forward, Maringhi set a portion on her plate before serving himself. When she looked over at him, surprised, he just inclined his head before returning to his conversation.

Artemisia took a bite and nearly moaned. The meat was hare, dark and strong, and had been roasted with herbs into a tender sauce. She wished she had been given an idea of how many courses the Medici would be serving—she could have happily filled her stomach with the pappardelle.

In the end, they served three more courses: a refreshing salad with croutons and peaches, a full roast peacock with its plume intact, and, for dessert, trays of morzelletti. The small cookies were topped with marzipan, an expensive almond paste. The wine continued to pour freely, and Artemisia’s head grew light and her limbs heavy.

She was here. Florence. In the Medici’s fortress, surrounded by the city’s elite. If someone had told her two years ago that she would find her way out of Rome, defy her father’s instructions to marry, and still end up here, she would have lambasted them for tormenting her with dreams that would never be.

She was torn between triumph and brooding when someone coughed beside her. The rest of the table was starting to peel away, leaving to continue drinking in another room or heading out for the night, but Maringhi was still seated beside her.

“I’m sorry,” he said quietly. “I feel as though I unintentionally offended you several times tonight. That wasn’t my goal.”

“You opened by mocking me about the silverware,” Artemisia reminded him.

“Well,” he said with a crooked grin, “some of it was intentional teasing. You seemed so solemn.”

Artemisia blinked. It had been a long time since she had been invited into a joke, rather than suffering as the target.

When she couldn’t summon an answer, he simply nodded. “As I said, my apologies. I hope you have a pleasant night.” He finished the last of his wine and left the table.

Artemisia looked after him. Though he’d had as much wine as anyone else, he walked with smooth confidence. She shook her head and drained her own drink.

Jacopo found Artemisia before she could leave and insisted on introducing her to a variety of local patrons and other artists. Their names and faces—all male, all older than her—became a blur within minutes. She leaned on Jacopo’s arm to keep her balance.

Artemisia caught Madama Cristina’s eye across the room. She was standing with her son, who was recognizable even at a distance. To her surprise, the Grand Duke Cosimo II was close to her age. She had heard that he had taken over his father’s role at only nineteen, but he had always seemed larger than life. Following his mother’s example, he was a great patron of the arts, and everyone in Rome spoke of him and his influence in hushed tones.

At a whispered word from his mother, he looked at Artemisia and raised his glass.

* * *

By the time Artemisia stumbled up the stairs back to her small studio after the dinner at the Medici palace, it was well after midnight. It was fortunate that she lived so close to the Palazzo Pitti—she