9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

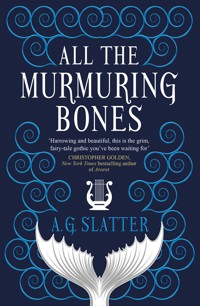

For fans of Naomi Novik and Katherine Arden, a dark gothic fairy tale from award-winning author Angela Slatter. Harrowing and beautiful, this is the grim, fairy-tale gothic you ve been waiting for CHRISTOPHER GOLDEN, New York Times bestselling author of Ararat Long ago Miren O'Malley's family prospered due to a deal struck with the mer: safety for their ships in return for a child of each generation. But for many years the family have been unable to keep their side of the bargain and have fallen into decline. Miren's grandmother is determined to restore their glory, even at the price of Miren's freedom. A spellbinding tale of dark family secrets, magic and witches, and creatures of myth and the sea; of strong women and the men who seek to control them.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Praise for All the Murmuring Bones

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

Author’s Note and Acknowledgements

About the Author

PRAISE FOR ALL THE MURMURING BONES

‘A. G. Slatter is a born storyteller. Her work is as beautiful and dangerous as the best fairy tales and All the Murmuring Bones is entirely enchanting. A magical read!’

Alison Littlewood, author of A Cold Season

‘A beautiful gothic monstrosity (monstrosity being a good thing), one of those rare books you don’t just want to read but want to live inside of.’

Mike Mignola, creator of Hellboy

‘Like J.R.R. Tolkien, Slatter’s taken her personal invented mythos and crafted a world around it that is at once familiar and deeply strange. Lush and chilling, eerie and exquisite, brutal and elegant… I defy anyone to stop turning pages until they’ve come to the end.’

Ellen Kushner, author of The Privilege of the Sword

‘Harrowing and beautiful, this is the grim, fairy-tale gothic you’ve been waiting for. All the Murmuring Bones is Slatter at her darkest—and finest. Don’t miss it!’

Christopher Golden, New York Times bestselling author of Ararat and Red Hands

‘All the Murmuring Bones is fairy-tale gothic at its finest and then some. Luscious, richly infused with Slatter’s gift for creating place; this is a world that invites travel along all of its dark roads and secret paths. Long after you’re done with the book, you’ll sit there drenched still in its magic, wondering how you might find your way back.’

Cassandra Khaw, author of Hammers on Bone

‘A story as gorgeously gothic as its title. This is a novel of blood and bones, of salt and silver, of an absolutely haunting richness. I was compelled from the very beginning and held rapt to the end.’

Kat Howard, author of An Unkindness of Magicians

‘Like the sea at its heart, Slatter’s haunting story is treacherous and lovely in all its dark depths.’

Heather Kassner, author of The Bone Garden

‘Two uncanny houses, Hob’s Hallow and Blackwater, bookend Angela Slatter’s new novel like grim sentinels. Whether they are cursed or enchanted, majestic or moldering, refuge or prison, only reading to the end will tell. Meanwhile, the landscape stretching between these gothic structures abounds with corpsewights, kelpies, ghosts, rusalki, werewolves, clockwork mechanicals, and —most alarmingly—actors. And across this treacherous terrain walks Miren O’Malley, scarred, furious, and growing in power. All the Murmuring Bones is brutal and beautiful throughout, with moments of tenderness hard-won and harder-kept, and, pervading all, an atmosphere of inescapable threat like the taste of salt wind and the sound of silver bells ringing in the deep.’

C. S. E. Cooney, World Fantasy Award-winning author of Bone Swans: Stories

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Print edition ISBN: 9781789094343

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789094350

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: March 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2021 A.G. Slatter. All Rights Reserved.

A.G. Slatter asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To Betty and Peter, my parents and patrons of the arts– or my art at least.

1

See this house perched not so far from the granite cliffs of Hob’s Head? Not so far from the promontory where once a church was built? It’s very fine, the house. It’s been here a long time (far longer than the church, both before and after), and it’s less a house really than a sort of castle now. Perhaps “fortified mansion” describes it best, an agglomeration of buildings of various vintages: the oldest is a square tower from when the family first made enough money to better their circumstances. Four storeys, an attic and a cellar, in the middle of which is a deep, broad well. You might think it to supply the house in times of siege, but the liquid is salty and partway down, below the water level, you can see (if you squint hard by the light of a lantern) the silver crisscross of a grid to keep things out or in. It’s always been off-limits to the children of the house, no matter that its wall is high, far higher than a child could accidentally tip over.

The tower’s stone – sometimes grey, sometimes gold, sometimes white, depending on the time of year, time of day and how much sun is about – is covered by ivy of a strangely bright green, winter and summer. To the left and right are wings added later, suites and bedrooms to accommodate the increasingly large family. The birth date of the stables is anyone’s guess, but they’re a tumbledown affair, their state perhaps a nod to lately decaying fortunes.

Embedded in the walls are swathes of glass both clear and coloured from when the O’Malleys could afford the best of everything. It lets the light in, but cannot keep the cold out, so the hearths throughout are enormous, big enough for a man to stand upright or an ox to roast in. Mostly now, however, the fireplaces remain unlit and the dormitory wings are empty of all but dust and memories; only three suites remain inhabited, and one attic room.

They built close to the cliffs – but not too close, for they were wise, the first O’Malleys; they knew how voracious the sea could be, how it might eat even the rocks if given a chance, so there are broad lawns of green, a wall of middling height almost at the edge to keep all but the most determined, the most stupid, from toppling over. Stand on the stoop of the tower’s iron-banded door (shaped and engraved to look like ropes and sailors’ knots). Look ahead and you can see straight out to sea; turn to the right but a little and there’s Breakwater in the distance, seemingly so tiny from here. There’s a path, too, winding back and forth on itself, an easy trail down to a pebbled shingle that stretches in a crescent. At the furthest end, there was once a sea cave (the collapse of which no one can recall), a tidal thing you wouldn’t have wanted to be caught in at the wrong time. A place the unwary had gone looking for treasure as rumours abounded that the O’Malleys smuggled, committed piracy, hid their ill-gotten gains there until they could be safely shifted elsewhere and exchanged for gold to line the family’s already overflowing coffers.

They’ve been here a long time, the O’Malleys, and the truth is that no one knows where they were before. Equally no one can remember when they weren’t around, or at least spoken of. No one says “Before the O’Malleys” for good reason; their history is murky, and that’s not a little to do with their very own efforts. Local recounting claims they appeared in the vanguard of some lord or lady’s army, or one of those produced by the battle abbeys in the days of the Church’s more intense militancy, perhaps one marching to or from the cathedral city of Lodellan when its monarchs fought for land and riches. Perhaps they were soldiers or perhaps they trailed along behind like camp-followers and scavengers, gathering what they could while no one noticed, until they had enough to make a reputation.

What is spoken of is that they were unusually tall even in a place where long-legged raiders from across the oceans had liberally scattered their seed. They were dark-haired and dark-eyed, yet with skin so terribly pale that on occasion it was muttered that the O’Malleys didn’t go about by day, but that wasn’t true.

They took the land by Hob’s Head and built their tower, called it Hob’s Hallow; they prospered quickly. They took more land, and gained tenants to work it for them. There was always silver, too, in their coffers, the purest and brightest though they’d tell no one from whence it came. Next they built ships and began trading, then built more ships and traded more, roamed further. They grew rich from the seas and everyone heard tell of how the O’Malleys did not lose themselves to the water: their galleons and caravels, their barques and brigs did not sink. Their daughters and sons did not drown (or only those meant to) for they swam like seals, learned to do so from their first breath, first step, first stroke. They kept to themselves, seldom taking wives or husbands who weren’t of their extended families. They bred like rabbits, but the core of them remained tightly wound around a limited bloodline; those bearing the O’Malley name proper were prouder than all the rest.

They paid naught but a passing care for the opinion of the Church and its princes, which was more than enough to set them apart from other fine families, and made them an object of unease and rumour. Yet they kept their position and their power for they maintained the impression of worship for the sake of appearances. They were neither stupid nor fearful. They cultivated friends in the highest of high places, sowed favours and reaped the rewards of doing so, and they gathered secrets and lies from the lowest of low places. Oh! such a harvest. The O’Malleys knew the locations of all the inconvenient bodies that had been buried – sometimes purely because they’d put those bodies there themselves. They paid their own debts, made sure they collected what was theirs, and ensured all who dealt with them knew that what was owed would be returned to them one way or another.

They were careful and clever.

Even the greatest of the god-hounds found themselves, at one point or other, beholden to them. Sometimes an ecclesiastic of import required a favour only the O’Malleys could provide and so, hat in hand, he came. Under cover of darkness, of course, in a closed carriage with no regalia that might give him away, on the loneliest roads out of Breakwater to the estate on Hob’s Hallow. He’d take a deep breath as he stepped from the conveyance, then another as he looked up at the lofty panes of glass lit from within so it seemed the interior of the tower was on fire. He’d clasp the golden crucifix suspended at his waist for fear that, upon crossing the threshold, he might find himself somewhere more infernal than expected.

More than one such man made visits over many years. Yet men of this sort mislike owing favours to anyone – especially women, and there was a time when females held the O’Malley family reins – and those very same priests offered all manner of excuses, threats and coercions trying to avoid their obligations. None worked, and the brethren found themselves brought to heel each and every time: an archbishop or other lordly cleric was unseated and moved on like some common mendicant, and the smile on the lips of the matriarch was wide and red.

It was the sort of loss – an outrage – that had never been forgotten, not in several hundred years, and it was unlikely to ever be. Indeed, the Church’s memory was long and unsleeping, and in each successive generation one of its sons at least had sought a way to make the family pay. No matter that the O’Malleys had given a child to the Church for as long as anyone could recall, that they paid more than their tithes required, and supported several almshouses in the city. They even had a pew with their name on it in Breakwater’s cathedral where they sat every Sunday whenever in attendance at the townhouse they maintained in one of the fancier districts. Oh, their boredom during services could barely be contained, but they kept the form.

No, an insult once given to the Church was never forgotten nor forgiven, and generations of godly men had devoted a good deal of their lives to ill-wishing the O’Malleys past, present and future. Much effort and energy were consecrated to the cursing of the name, gossiping about the source of their prosperity and plotting to take it from them. Many was the head shaken in rue that pyres and pokers were not options available as a means of enforcing conformity in this particular instance – the webs woven by the clan were too strong to be evaded or undermined.

It wasn’t only the more godly members of Breakwater society at odds with those who lived out on Hob’s Head. Those who took O’Malley charity or made good-faith bargains with them often found that the cost was much higher than could have been imagined. Some paid it willingly and were rewarded for their loyalty; those who complained or baulked were justly requited. As time went on, business partners thought twice about joining O’Malley ventures, and the more cynical counted their fingers twice after shaking hands on a deal, just to make sure all digits remained. Those who married in – whether to the extended branches or the main – did so at their peril. More than a few husbands and wives were deemed untrustworthy or simply inconvenient when passion had run its course, and were disposed of quietly.

There was something not quite right with the O’Malleys: they didn’t fear like others of their ilk. They, perhaps, put their faith elsewhere. Some said the O’Malleys had too much saltwater in their veins to be good and god-fearing, or good anything else for that matter. But nothing could be proven, not ever.

Their dealings were discreet, but things done ill always leave echoes and stains behind. Because they’d been around for so very long, the O’Malleys’ sins built up, year upon year, decade upon decade, century upon century. Life upon life, death upon death.

The family was simply too influential to be easily destroyed but, as it turned out, they brought themselves down with neither aid nor agitation from either Church or peers.

It was their bloodline that faltered first – although no one but they knew – and their fortunes followed soon after. Fewer and fewer children were born to the O’Malleys proper, but for a while they’d not been bothered, or not overly so, for it seemed like nothing more than a brief aberration. Besides, the extended families continued to multiply, and to prosper financially.

Then their ships began to sink or be taken by pirates; then investments, seemingly shrewd, were quickly proven unwise. The great fleet was whittled down to a couple of merchant vessels making desultory journeys across the seas. Almost all their affluence bled away, faster and faster, until within a few generations there was just the grand mess of a home on Hob’s Head. There were rumours of jewellery, silver and gems buried beneath the rolling lawns – no one could believe it was all gone – but the O’Malleys had too many debts, too little capital, and their very blood was running thin…

And so the family found itself much diminished in more ways than one. Unable to pay its creditors and investors, unable to give to the sea what it was owed, and with too few of other people’s secrets to use as currency, the O’Malleys were, at last, in danger of extinction.

The estate used to be carefully tended by an army of gardeners and groundsmen, but now there’s only ancient Malachi – barely breathing, regularly farting dust – to take care of things. All the walled gardens are overrun; to enter them would be to risk having sleeves and skirts torn by thorns and branches with too much length and strength, and their doors are sewn shut with brambles. All but one that is, the one the old woman – the last true O’Malley – uses when she seeks fresh air and solitude. In the house, Malachi’s sister, Maura – younger by a little and less given to farting – does what she can to keep the gilings and decay at bay, but she’s one woman, arthritic and tired and cross; it’s a losing battle, though she keeps her hand in with herb magic and rituals to ensure the kitchen garden continues producing vegetables and the orchard fruiting. There are two elderly horses to pull a rickety calash and be gently ridden; three cows, all almost beyond giving milk; several chickens whose lives are likely to be short if they do not begin to take their duties more seriously. Their years of being productive have been extended by Maura’s tiny rituals, but there’s only so much small magics can do. Once, there was a legion of tenants who could be called upon to work the fields, but now they are few and the land has laid fallow for a very long time indeed. The great house is crumbling and the massive curved iron gates at the entrance have not been closed in a decade for fear any movement will tear them from their rusted hinges.

There’s just a single daughter left of the household, whose surname isn’t even really O’Malley, her mother having committed the multiple sins of being an only child, a girl, insisting from sheer perversity on taking her husband’s name, and then dying without producing further offspring. Worse still: this husband had no O’Malley lineage – not a drop – so the daughter’s blood was thinned once again. She’s eighteen, this girl, a woman really, raised mostly in isolation, taught to run a house as if this one isn’t a ruin waiting to fall, with a dying family (decreased yet again by a recent death), no fortune, and no prospects of which to speak.

There’s an old woman, though, with plans and plots of long gestation; and there’s the sea, which will have her due, come hell or high water; and there are secrets and lies which never stay buried forever.

2

‘He was a terrible husband, you know, Miren,’ my grandmother says with a sigh.

We’re watching the coffin (a death-bed made at great expense to ensure he stays beneath; golden locks and hinges, padded silk interior stuffed with lavender which calms the dead, the joins sealed with eldritch adhesive over which spells have been sung) be carried down, down, a’down into the crypt beneath the chapel floor. The pallbearers have paced across the painted labyrinth of a pilgrim’s path that decorates the aisle, and now they’re at the great dark void in front of the altar. The flagstones have been pulled up so my grandfather Óisín can be laid to whatever might count as rest for him. Some of the mosaic tiles – merrows and ships and things with wings that might resemble angels in poor light – have been chipped. Someone (Malachi) was careless. I hope Grandmother doesn’t notice, but chance would be a fine thing. Someone (Malachi) will hear about it, either today or tomorrow; later, if she’s decided to hold fire and use the sin at a time when more of an impact can be made, more of a fuss.

No one bothered to light the candles on the wooden chandelier above our heads – an oversight – but the daylight throws beams of colour through the arched stained-glass windows. Still, it takes a while for the eye to adjust in the gloom, and I keep waiting for someone to trip over something, anything, their own feet most likely. It’s cold, but then it always is here, surrounded by rough-hewn stone. I can smell the sea air and mildew beneath the wafts of burning incense. I put an arm around my grandmother’s shoulders because she’s shivering, but that might just be advanced years – mind you, I can feel the muscles beneath her gown, built by years of daily swimming in the sea. She never misses a morning: swam the day my grandfather died and swam today, the day we’re putting him in the ground. She gives me a glance, does Aoife O’Malley, barely tolerating the gesture – we’re of a height and age hasn’t stooped her at all – but I keep the arm there as much to annoy her as to give myself some skerrick of warmth. Besides, I feel the eyes of all the relatives on us and, as prickly as Aoife might be, I do want to protect her from those who think her weakened by the years, easy prey.

The priest come all unwilling, to send the old man off keeps intoning his prayers but they sound like maundering to me. Once, we’d have warranted a bishop from Breakwater, at the very least – he’d have been no less unwilling, I grant you, but we were worth more at one point, and they’d not have dared to deny us. But now… a low-level god-hound with black half-moons under his nails, smelling of alcohol and earth, a fine fall of dandruff on his shoulders like winter’s come early. Mumbling his prayers as if afraid his chosen god might strike him down for attending here, for laying Óisín O’Malley into the dirt, like it’s a seal of approval. Mind you, there’s not much choice of clergymen left in Breakwater anymore, no matter what your standing.

‘He was a terrible husband, you know,’ repeats Aoife as if wittering, but I know enough to do nothing but nod. She’s putting up a front, is my grandmother: harmless old lady, recently bereaved. Bereaved of a terrible husband certainly, but leaving no doubt for those in earshot that she’ll still miss him terribly, because she was a good wife in spite of him. In the face of marital adversity, she, Aoife O’Malley, did her very best to be a tender, loving, considerate, respectful spouse.

Which is precisely what she was not. But, as I say, I’m not fool enough to contradict her in front of others. Though we might bicker when it’s just us, I’m loyal in public, no matter what. All these relatives from various family offshoots are here only to see what they might get out of the old man’s death. And they’re not proper O’Malleys, not true ones, pedigree all mixed and mingled – like myself – the products of marriages made with men and women not of our line. Their blood thinned. Honestly, though, such breeding had to be done, for all my grandmother laments it. How many times can a line fold back on itself without bringing forth a monster? Gods know, we’ve had our share, and Malachi’s whispered to me that there are strangely made coffins down there in the earthy deep, hiding the secrets no one else would keep.

But Aoife’s an O’Malley twice over: born one and then married to one. She’s proper, double-blooded, the omega. The rest of us are lesser, children with ichor so thin it barely matters. But I was raised in this house, I’m Aoife’s granddaughter; I’m one step above the others.

Yet she is the last here of purest lineage.

The cleric’s mutterings bounce back up while the strongest of the cousins follow him, carrying Óisín’s mahogany coffin (extra long to accommodate his height, adding to the cost) into the depths. I can see Aidan Fitzpatrick’s strong back, shoulders broad beneath his coat, hair so blond and bright even in the darkness as they descend. Finn O’Hara’s beside him, and the height disparity makes the going awkward. I think of Óisín tilting inside the box, pressing up against the padded lining, though he’ll know nothing of it. Behind them are the Monaghan twins, Daragh and Thomas, then bringing up the rear two cousins so distant that I can’t even recall their names. At least they look like O’Malleys. The others are blond or ginger, skin freckled or sallow, marking them out. Or once it would have; now those who actually look like proper O’Malleys are in the minority.

Aoife and I are the only ones in the front pew, even though there’s naught but standing room at the back of the small chapel. No one dared to sit beside us, or even across the way. I’m unsure if it’s that proximity to Aoife is a situation to be avoided, or no one wanted to get too close to Óisín’s coffin just in case he popped up again, shouting at them all to go home; possibly some alchemical combination of the two.

Me? I’m nothing to avoid; there’s nothing frightening about me.

Mostly, I suspect the crowd has come to make sure Óisín is truly gone, and that can be done from a comfortable distance. I know his faults all too well, but I’ll miss my grandfather sorely. He taught me everything I know about the sea and its moods, about ships, about business, and all the superstitions that sailors are heir to. I suffer no illusions: if I’d had brothers, if my mother’d had brothers, there’d have been little chance of me getting the education I did. The days of the O’Malley women’s power being unquestioned are long gone, and more’s the pity. Aoife’s a rare creature, a force of nature, elemental, my grandmother, utterly uninterested in others telling her what to do, but even she’s had to bow her head and give in now and then.

I think, some days, that Óisín was lonely and he liked my company, in his study here and on the trips into Breakwater, inspecting the vessels and cargo. He liked taking me for lunch in his favourite club, quizzing me about tides and knots and trade routes. Mind you, if I got anything wrong I never heard the end of it, and was left in no doubt as to what a disappointment I was. But I made a point of not getting things wrong, not after the first few times. In my pocket I can feel the weight of the small knife that was his, its handle inlaid with mother-of-pearl, given to me before he took to his bed for the last time.

‘A terrible husband,’ sighs Aoife yet again, louder for those in the back, just in case anyone missed it. Third time’s a charm: she’s making it a fact to be carried forward and forth by all those whose ears it touches. Aoife O’Malley’s always believed that the truth is what she says it is.

This time I reply, ‘Yes, Grandmother,’ though I feel a little disloyal, but Aoife’s the one I’ve got to live with now. No buffer any longer, even if that buffer was nothing more than Óisín’s desire to gainsay his wife.

The pallbearers seem to be taking an awfully long time down there, and there’s no longer even the rhythmic whine of the godhound’s chant. I strain my ears, listening for the sound of boots on steps, or wood on stone as they shift the coffin into one of the niches, perhaps a cough or two in the stale air of a tomb that’s not been opened in fifteen years, not since my mother died of fever, following my father by a mere week.

I listen harder still, hear twice as much nothing. I know better, yet the absence makes my heart beat faster. I imagine everyone can hear it, but Aoife doesn’t look at me, registers no sign. What’s happening down there? Did they go too far? Did the stairs change? Grow in number, descend further? Are my cousins even now being welcomed somewhere unaccountably warm? From habit, I touch the spot just beneath the dip in my throat, feel the thick black fabric of my high-necked dress and the warm lump of metal under it: a silver necklace with the ship’s bell pendant engraved with what might be scalloping or fish scales. Aoife also wears one; she says my mother did as well. As all the firstborns did.

Listen, listen, listen…

Aoife’s delicate head turns and she stares at me through the thick lace veil. I realise I’ve been squeezing her shoulders. I loosen my grip and press out a smile from behind my own veil; not as thick as hers, but then I’ve less to hide.

Footsteps at last! As if all they’ve been waiting for was the release of my tension. The cousins emerge, two by two – do they look paler than when they went in? Daragh, a little faint? Has Thomas finally let his breath go, gasping as if he’d held it in the whole time he was below? Only Aidan appears indifferent: a duty has been done and he’s been seen to do it. Nothing more.

He’s got the family height, but that’s all. Thinning blond hair, blue eyes, and beneath his costly, well-tailored frockcoat (only the truest of O’Malleys have been afflicted with this grinding embarrassment of poverty), he’s fighting fat. In his thirties, he’ll keep it away only as long as he maintains daily physical activity: the riding, the boxing, the tramping across the hills, bestriding the decks of the ships he owns. He looks at Aoife, but not at me; then again, he seldom bothers to address me beyond ‘Hello’ and ‘Goodbye’, as if I’m still a child, the little cousin, safely almost-invisible. I’m used to that, and comfortable with it. They exchange a nod, then he returns to the second-row pew where his sister Brigid – once my friend – with her pale eyes, soft curls and weak chin waits. I imagine I feel the heat of her glare on the nape of my neck, but that could be sheer fancy. The others disperse to the back of the chapel.

The priest intones a final blessing and bids us go in peace. Aoife wastes no time; we progress down the aisle at a sprightly pace she might want to reconsider in her guise as a fragile grieving widow. I squeeze her arm, and she gets the message after a moment. Her speed falls away a little, steps become smaller and slower, no longer those earth-eating strides to put men half her age to shame.

Behind us come the relatives and remnants. I glance over my shoulder and watch them through the black froth of lace as they pour along in our wake like well-trained waves, as if afraid we might escape if not quickly pursued.

‘Just this last trial to get through,’ murmurs Aoife.

‘Yes, Grandmother,’ I say, but I’m thinking, What then? How do we go on? How do we return to embroidery and reading, managing those three tenant families and Maura and Malachi, tending the herb garden and testing their properties, riding those ancient horses, walking the sea brim, making do from one day to the next? How?

And there is, I must admit, the thought singing at the back of my mind that there is only Aoife now, and when she is gone I might leave Hob’s Hallow and all the obligations of this place and the O’Malley name behind me.

* * *

‘How’s our darling Aoife, Miren dear? Is she quite well?’ asks Aunt Florence Walsh, who’s really just another cousin, yet so old it’s easier to call her “aunt”. She’s short and round, but none of the fat remains in her face, which means she’s wrinkled with sunken cheeks. Wrapped in black, she looks like a prune topped with silver hair that appears soft as a cloud. I can tell from experience it’s nothing of the sort: as a child I touched it, expecting floss, yet finding something sharp and dry and prickly. I felt for days afterwards that there were shards beneath my skin, and I was slapped for my trouble, which I never forgot.

‘She is very well, Aunt. How kind of you to ask.’

It’s nothing of the sort. The old carrion bird is younger than Aoife by a few years but looks older. In her head, I think there’s a race to see who survives longest; I wonder how many others are taking bets. I know who I’d put money on, if I had any.

‘She’s very adaptable, our Aoife; I’m sure she’ll survive whatever life throws at her.’ Aunt Florence reaches towards me, touches the tiny pintucked frills on my sleeve as if to judge their value. This gown is old, greening with age for it’s not even mine – my mother’s, I think, and worn at her own grandparents’ funerals. I suspect it belonged to another O’Malley or three before that. The style is antique, but all that matters is that it’s black; Maura took the waist in a little, for I’m more slender than Isolde was. For a moment I consider slapping away the spidery hand with its grasping fingers, a long-delayed revenge, but her bones would probably shatter. It’s tempting, though.

‘And so resourceful. Look at all this!’ She gestures to the spread of food and drink laid out in the long hall once used for balls when we could afford to entertain. Sideboards circle the walls and tables form a line up the middle; all are weighted down with provisions. Everything’s (well, in this room) been cleaned and polished and tidied by the four maids Aidan Fitzpatrick “loaned” us, an unusual attention to duty for this last office for my grandfather. Both Aoife and I have grown used to a light fall of dust most of the time, with even my grandmother accepting that Maura’s getting too old for much beyond rubbing a cloth across easily reachable surfaces in a desultory fashion. Florence’s icy blue eyes gleam as she says, ‘Most impressive with such a pinched purse.’

‘Grandmother can be most persuasive when she wishes, Aunt, as you and Uncle Silas well know.’ Florence’s husband, long gone, unlamented by most, was rumoured to have been talked out of a good portion of money not long before his death; never paid back either as Aoife had also convinced him that the debt should be forgiven in his will. Even more rumours abound as to how she managed to sway him. Aoife is, as Florrie’s observed, resourceful. Ruthlessly so.

Aunt’s face convulses; the benign expression she tries so hard to cultivate simply cannot stand against the malignance that lives inside and it pushes up like some great sea creature surfacing. A glimpse, then it’s gone. I’m not afraid of her, but for a moment my knees felt shaky, perhaps because in that moment Florence looked rather like Aoife. Not in the features, no, but the ill-intent.

‘You’ve got more than enough of her blood,’ she says, and it sounds like a curse. She smiles. ‘I’m glad she’s well. Take care of yourself, Miren.’

Aunt Florence moves off, slowly, and I watch as she makes her way through the press of black-clad bodies. She stops here and there to say something, touch someone. Some recoil from her; others lean in.

The crowd seems to have thinned, but I doubt it’s because anyone’s left yet – although those planning to get back to Breakwater before dark will want to go soon. Relatives will be wandering the house, of course, spreading like webs from wing to wing to see what they can see. It’s not often they have the chance nowadays to visit; invitations to dine have been thin on the ground for some years. Hopefully they’ll not steal anything; not because they need to steal, but because a souvenir is something to crow about in future. They’ll be hard-pressed to find anything of value; even the multitude of silver objects – vases, busts, plates, cutlery, door handles, jugs, goblets, what-have-you – have gone, sold to pay bills over the decades. Only Aidan Fitzpatrick’s been a regular caller, asking after Aoife and Óisín’s health, checking if they need anything but not, I’ve noticed, actually giving something of consequence. Just enough to stave off the bailiffs, not enough to rescue them.

Us.

Florence disappears from my view and I glance again at the feast. How many more creditors will this bring to our door? How did Aoife coax anyone to extend credit? She knows as well as I do there’ll be nothing going spare after Óisín’s will is read. We’ll be lucky to keep the house, but the last of the ships will need to be sold off to cover what’s owing.

Not to mention the death duties.

Once, we’d have known what they might be, what portion, but there’s no longer a council to decide that. It’s been thus for almost four years, since a woman arrived in Breakwater and began to make it her own. The gathering of men who’d governed gradually died off, apparently naturally or accidentally, and those who remained were happy to benefit from Bethany Lawrence’s new order. She has her finger on the pulse of the city and where she applies pressure, it either speeds up or halts altogether. The tales we hear from the tinkers who travel the length and breadth of the land say she’s called the Queen of Thieves behind her back (sensibly), and she gathers taxes and bribes and tithes as surely as both Church and State once did (the archbishop, too, is her lapdog, by all accounts, accepting whatever scraps she throws to him). Mind you, it’s said she keeps the municipality clean and well-run. What might she demand from us? Rumour has it that the rich families of Breakwater have found themselves either providing coin or favours when an inheritance is in the offing, sometimes both. It strikes me as the sort of deal an O’Malley might once have made, but she’s not one of us. Neither Aoife nor Óisín have had contact with her and she’s never approached either in person or via go-between; a sure sign of how insignificant we’ve become, that predators don’t give us even a glance. Or perhaps, just perhaps, some of our reputation remains, some echo that makes even the powerful wary.

Perhaps we’ll hear nothing. Perhaps our poverty is too deep, too known, for anyone to bother demanding anything of us. One can but hope.

‘Miss, shall I put out more of the salmon?’ One of the borrowed maids appears at my elbow.

I shake my head. ‘No, it will only encourage them to stay.’

The girl bobs her head, gives a curtsey and moves off.

Soon they’ll all be gone, these family members here to see what they can see, not to give comfort in a time of need, merely to celebrate that it’s not us who’ve gone beneath.

I remember Óisín as I sat by him in the days before the reaper came. There was no pale wailing woman at the window, nor did a storm blow up when he died – that only happens when the women go; no one knows why, or if they do no one’s saying. I remember my grandfather becoming a scared child, shrunk into himself on the vast mattress where our matriarchs and patriarchs have bred and slept and died. I remember him weeping that no one would lament his passing, a sudden wish, a need for affection when he’d never given much himself. And I wondered at that, that he’d be yearning not for absolution for his sins, which surely must be numbered in a very large book, but for love.

Yes, soon they’ll all be gone and it’ll just be Aoife and me, rattling about at Hob’s Hallow as it decays around us, Maura and Malachi teetering along the lip of the grave. Yet I cannot see beyond the moment when the door closes behind them all; cannot truly imagine what shape my life might take in the weeks and months to come. It’s like enduring a storm, I suppose, though a strangely quiet one: Just hang on, Óisín used to say, and I hear his voice now, hang on to whatever’s solid. A seaman’s mantra. What he’d tell me whenever Aoife took me swimming in the sea.

And abruptly I’m aware of the hole in my middle: the old man will be missed. I clench my fists, press them against my stomach, and blink hard to keep the tears away as I take the steps, twenty, thirty, to get to the expanse of windows at the other end of the ballroom. If I know anything for certain it’s that neither love nor hate is ever simple.

Some cousins try to speak to me, but I move past as if I’ve not heard and they fall away. At last, I’m standing in front of the bank of diamond-shaped panes, staring out.

The overgrown lawn is the brightest of greens, rolling gently away to the cliffs. Both sky and sea are grey; the optical illusion of it makes it seem as if they’ve been stitched together, a patchwork quilt with only the subtlest of seams showing. It looks like the horizon is missing; what might happen if that line were gone? That line to which we all head, knowing we’ll never catch it, but driven toward it like a seabird following a migration path year after year, life after life.

I imagine the sound of the waves because I can’t hear it in here over the murmur of voices, the clink of fine china tea cups, the chewing, the tap of boots across marble floors. But I know it thuds and retreats with the constancy of a heartbeat, the shush and crash as it hits the shingle down below. Just the thought of it helps to calm me, which is funny because when I was very small I was so terribly scared of the noise. All the waters in the world are joined, Miren, Aoife used to say – what use being afraid of them?

That was neither help nor comfort, of course, when she was teaching me to swim by throwing me into the icy sea. That’s how I learned, unwillingly; she kept heaving me in no matter the weather or how I wailed. She would toss me off the rocks that erupted from the water (not so far from the collapsed cave) and I would sink. The first few times she rescued me; then she let me go. Let me plummet for so long that I thought I’d drown and I realised the only way to survive was to save myself with the long strokes and powerful kicks Aoife herself used. I’ve wondered for years if she’d have let me perish in the end… or if I’d waited just a moment more would she have dived in after me again, pulled her hopes and future from the waves in the form of a sputtering, coughing, terrified three-year old?

Just hang on to whatever’s solid, Óisín would say, but it took me a long time to realise he meant I had to rely on myself: I was the only solid thing in that angry sea.

How long I stare is a mystery, but I’m pulled from my reverie when I see two figures striding across the grass. From their direction they’ve come out from under the postern gate and are heading towards the spot where the church once stood, however briefly. One is in a long black mourning gown, the wind plucking at her veil, which she flings back with irritation so it trails behind her like a wing.

‘What’re they talking about, do you think?’

I didn’t notice Brigid come up beside me. She’s short and dumpy, blonde curls, pale grey eyes, but her voice is lovely and she sings when asked. No one asked her for Óisín’s sending-off, but then no one sang him away at all.

I glance sideways at my cousin. The colour in her cheeks is high as if she’s annoyed or embarrassed or she had to work up the courage to speak to me or she’s afraid I won’t reply. We’re not friends. Not anymore. Once we were. When Óisín still ran the office in Breakwater – before he sold it to Aidan – I would get to visit with Brigid. She would come out to Hob’s Hallow too, and we would play. It didn’t matter, then, that she wasn’t a “proper” O’Malley; I didn’t listen to Aoife’s contempt for the lesser branches. It went on for years and I thought she was my best friend, but when you’re fed crumbs of resentment and pride, when you lose trust in someone…

‘I don’t know,’ I say. Then add, because there’s no shame in it, at least not for me, ‘Perhaps a loan.’

‘This house will fall, you know.’ Yet she says it with no trace of spite, just a kind of sadness, like she’s speaking of an old pet soon to die.

‘I know.’ And then we watch the two figures outside in silence.

Aoife’s almost as tall as Aidan; she’s talking avidly, hands waving. I can see her expression: sly, wary, hungry and smart. And Aidan, listening intently, looks a little like her. When he opens his mouth, the features rearrange into a different creature, the son of a thinned blood, and then both their faces are lost to me as their direction changes and they walk toward the camouflaged horizon, into a wind that carries the breath of a storm.

3

The library has a high ceiling, once painted with scenes of our maritime glory, but largely the art is obscured by cobwebs and smoke grime and has been for as long as I can remember. A face peeks through here and there, a limb, a roiling cloud, a ship’s sail, a sea monster’s tail, but mostly what’s there is up to the imagination. When I was small, I wouldn’t look lest I conjure a nightmare of those elements. Back then I thought there couldn’t be worse things than bad dreams. Three of the walls are covered by overflowing bookshelves, and the fourth is mostly window, swathed with red curtains, thick with dust, to keep the night and the worst of the cold at bay.

Aoife’s in an embroidered housecoat of the deepest maroon, hair piled high, silken silver, no trace of the darkness of her youth; there’s a glass of winter-lemon whiskey by her elbow and she’s seated in one of the threadbare wingback chairs, staring into the flames of the hearth. Not long ago she gave a deep sigh that I recognised as a letting go, a signal that from here we move forward. But to where?

I’m still in my mourning gown; I spent the afternoon farewelling guests, then helping Maura clean up the mess because Aidan took his borrowed maids home with him. Afterwards we packed three baskets with as many leftovers as possible, and I walked to the three tenanted cottages to deliver them. There’s more food than we can get through and someone at least should benefit somehow from Óisín’s passing. The Kellys and the Byrnes were grateful; the Widow O’Meara accepted what I brought but gave me the same look she always does, and I hurried away just as I always do.

I go to one of the shelves and take a book down from its place nestled between family histories, and tomes of maritime law that my grandfather loved more than anything of flesh and blood. There are many volumes with the golden “M” on their spine that denotes “Murcianus” – Murcianus’ Little-known Lore, Murcianus’ Mythical Creatures, Murcianus’ Strange Places, Murcianus’ Songs of the Night, Murcianus’ Book of Fables. There is even a Murcianus’ Magica, but it is an incomplete version, the true one having been lost centuries ago in the sack of the Citadel at Cwen’s Reach, or so it’s said.

But the one I take down is different, heavy in my arms, and I hold it almost like a shield as I approach Aoife. My fingers trace the embossing on the cover, no longer easily visible. In the front, I know, there are missing pages, nothing left but the tiny jagged shreds of paper like the edges of butterfly wings. It’s always been that way and Aoife claims not to know what was there; that the story, the very first story, was missing when even she was a girl and no memory of it has been kept.

‘Will you read to me?’ I ask without much hope, for I’m eighteen and Grandmother’s not read to me for the longest time. Maura, to whom I’d run for comfort as a child, never read me anything, but used to tell fairy tales. Maura’s singsong recountings were of children taken away to hidden places; of women turned into birds and bugs; of soul clocks and dark magic; of boys who sometimes went on two legs, sometimes on four; of girls who changed their faces, grew horns, and danced away from their old lives; of brides stolen by robbers and heroes laid low by a woman’s curse. And she told me, too, of places other than here: Lodellan and Bitterwood, Tintern and Bellsholm, and stranger places like Calder in the Dark Lands where the Leech Lords reign.

Aoife, when she was in the mood, would read from the book wherein generations of our kind have written tales that might be lies, might be true. Scribbled in different hands, some harder to decipher than others, but all ones that, as a child, I took as gospel.

Perhaps, too, I remember my own mother reading to me from the black-covered volume, the pages yellowed, discoloured with ink and age, with the fingerprints of the dead and tiny drawings to enliven or mar the margins. Perhaps I remember a voice sweeter than Aoife’s, gentler, more like to laugh than not, whose tellings were less frightening, so I did not wake from nightmares, but rather slept cradled in the arms of my ancestral memories. But perhaps I imagine it. Perhaps Isolde is merely a thought I once had and will never be anything else. But perhaps, just perhaps, my mother’s voice left a trace in my dreams. There’s not even a hint of a memory of my father, Liam; all Aoife’s ever said about him was that he was unsuitable and a few other words besides, none of them complimentary.

Other families might have stories of curses, cold lads and white ladies, but we have old gods, merfolk and monsters. I never doubted, when I was little, that these stories were true. Now, less a child, I’m not so sure.

But this night, for whatever reason, I need to hear such tales again and, for whatever reason, Grandmother is feeling generous and she nods. I place the book in her lap; the soaring points of her chair look like a throne with the wings of a bat. I curl on the green velvet chaise longue across from her, prop my head on a cushion, feel the warmth of the fire spread through me, knowing it will be too warm by the time the night is done, but not caring. I don’t ask for a particular recounting. It’s the telling that matters.

For the moment, there is peace.

And Aoife begins, in a voice that sounds only a little like an old woman’s, to read something I’ve not heard for many a year.

* * *

Three children there were in the house: the firstborn, a girl to inherit; the middle a boy for the Church; and the last another girl, and a grief it would be to her mother if she fulfilled her purpose. The family had argued it back and forth, but the order must be respected; they did not get to pick and choose, the children’s great-grandfather reminded.