1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

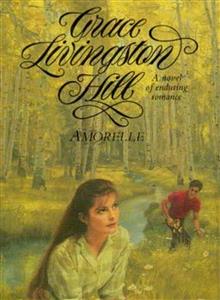

Amorelle is suddenly alone in the world when a handsome young man makes a proposal she cannot refuse.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Amorelle

by Grace Livingston Hill

First published in 1934

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Chapter 1

The minister sat in his study beside his desk, thoughtfully reading over a carbon copy of a letter written in his own characterful script.

His strong, kindly, spiritual face wore a troubled look as he considered each word earnestly, a shade of anxiety in his tired eyes, his firm lips set almost sternly. He wore the look of one who was going over once more a momentous decision to make sure he was right.

The hand that held the paper was fragile, and the flesh of his face was almost transparent from recent illness, but there was nothing fragile about his expression. Although a man of a natural sweetness and tenderness, he looked now like one girded for battle, and the reading of the letter might have been the polishing of his sword.

Presently he laid the letter on the desk and bowed his head upon his folded hands over it, as if in prayer.

That was not the first time he had prayed over that letter. He was a man of prayer and never made a momentous decision without resorting to his Guide. The letter had been written through prayer and after long consideration. A moment later he lifted his head, and the strong, gentle face wore a look of peace. He opened a drawer of his desk, took out a large manila envelope, put the letter into it among some other papers, and replaced it in the drawer, closing the drawer carefully.

Just then, Amorelle came hurrying down the stairs and entered the room with a worried look toward the clock. Her delicate face was a flowerlike replica of her father’s. She had the same mixture of sweetness and strength in her glance and the firm set of her lips.

“Father dear,” she said tenderly, a little reproachfully, “do you realize that it is almost eight o’clock and you are supposed to be in bed at half past seven? You know the doctor was very particular about it this first time you are downstairs. You are more tired than you know.”

“Yes, I know, dear, but I can’t go for a few minutes yet. I am expecting a caller, and he ought to be here any minute now. He was to come not later than eight o’clock.”

“Oh, Father!” said Amorelle in distress. “You mustn’t see callers tonight! You promised me and you promised the doctor that you would absolutely drop the parishional work until you were really strong again. You know the church does not want you to have any burdens to keep you from a quick recovery.”

“This is not parishional work, Daughter. This is a very important matter of business that has been causing me great perplexity and anxiety. It will not take five minutes to transact and then I will retire at once. I have not time now, but I will explain it to you later. I wrote and asked this man to come tonight, and it will distress me greatly if he does not come. Believe me, child, it will do me more harm than good for me not to see him. It will take very little time and then I can rest in peace. It is something that must be attended to at once.”

There was something in his quiet voice of authority, in the steady look of his keen blue eyes, that held Amorelle from protesting further. She stood, troubled, in the doorway, wondering whether she ought to call the doctor and get her father to bed in spite of his insistence. But while she hesitated the doorbell rang.

“There he is now,” said the minister, rising, his clerical dignity upon him like a garment. “Won’t you let him in, dear? It is Mr. Pike. Lemuel Pike.”

“Oh, Father! Lemuel Pike! How could he possibly be connected with anything important enough to risk your health? He is a sucker, that’s what he is, a selfish sucker! Everybody says so! He just wants to bleed you, borrow money or something. He always has made you look troubled every time he has called. Please, please, Father, let me tell him you are not well enough yet to see him.”

Amorelle’s voice was full of distress.

“No, Amorelle, I must see him. This matter is most important to me. You do not understand. I will explain when he is gone. Will you open the door or must I go myself?”

There was a look of determination on her father’s face that Amorelle knew well, a look she had learned to obey during the years, and she turned swiftly to open the door.

“I can’t let you stay but five minutes,” she said in a low voice, but pleasantly enough, to the tall, thin visitor who stood on the porch. “This is Father’s first day downstairs, and he ought to have been in bed half an hour ago.”

Amorelle wondered why it always annoyed her that this man’s eyes were set so close together.

“Your father sent for me!” said Lemuel Pike coldly. And he strode past her into the study, closing the door behind him.

Amorelle looked anxiously after him then hovered around the hall and parlor, not far from the study door. For some unexplained reason, she felt uneasy about this meeting. Her father seemed tired and worn. That transparent look in his face frightened her. She eyed the clock and listened for the slightest sound from the study but heard only a low murmur of voices now and then.

She went from one window to another, looking at the clock all the while. At last when the parlor clock had ticked out ten minutes after eight, she went to the study door and grasped the knob firmly, at the same time tapping lightly with her fingertips on the door, and then swinging it wide open.

“Father dear!” she said with a very good imitation of his own firmness. “I really must send you to bed at once or I shall have to call the doctor. You know I had very definite orders from him that I dare not disobey.”

She had a swift vision of the two men standing facing one another, her father with a bunch of bills in his hand and Mr. Pike holding a slip of paper. Had Lemuel Pike been borrowing money from Father, now when they were having such heavy expenses?

She gave the caller a quick, suspicious glance, and Lemuel Pike returned a malignant glance to her, deliberately folded the slip of paper, and put it into his pocket.

But when she glanced at her father again, he seemed astonishingly relieved and was answering her meekly enough, “Yes, dear, we are just done.”

Lemuel paused with his fingers still at his pocket.

“You don’t think you would be willing to rewrite this, leaving out that objectionable phrase, Mr. Dean?” he asked, looking away from Amorelle and giving the minister a meaningful glance.

“No, Mr. Pike, I have thought the matter over carefully, and I feel that it is written as it should be.”

Lemuel passed from the room without even a good night. At the front door he paused and gave a swift look back. Something made Amorelle turn back also. She saw her father bent over, groping on the floor for something. As they both looked, he turned back the corner of the rug and seemed to be feeling around.

“Don’t do that, Father!” she called sharply, fearsomely. “I’ll find whatever you have dropped in just a minute. You are exerting yourself too much!”

The close-set eyes of Lemuel gave another swift glance back. The minister seemed to be poking something under the rug and smoothing the rug back again.

“I’ve found it,” he said a bit breathlessly, slowly straightening up. “It was just my desk key that I dropped.”

But Lemuel’s look lingered thoughtfully, almost suspiciously, on him as he stepped reluctantly from the manse, leaving behind him that which he loved dearer than his life. Amorelle caught his glance. She never had liked Lemuel Pike. She felt that he was almost criminal now in coming to bother her father when he was just recovering from a serious illness. He ought to have known better even if her father did send for him. It was very likely that Lemuel had asked to come or else her father would surely never have sent for him at a time like this. She could remember that, for a number of years, every time her father had been to see Lemuel Pike, he had returned with distress in his eyes and had sat for long periods, looking off thoughtfully into space, with troubled brow and deep-drawn sighs.

Amorelle closed the front door forcefully and hurried back into the study. She found her father had sunken back into his big armchair, where he had been sitting most of the day, a bright look in his eyes but unutterable weariness on his white face.

“Well, it’ll be all right now, little girl!” he said in a weak voice, with a faint smile on his pale lips. “I was so afraid I would leave you without—” The last words were almost a whisper, a gasp. Amorelle looked at him in consternation.

“Sit still,” she said gently, trying to keep the fright from her voice. “I’ll get you some hot milk before you try to go upstairs.”

She hurried into the kitchen, hoping Hannah was still there, but Hannah had gone out to visit her sick sister for a while, and Amorelle had to heat the milk herself. When she came back with it, her father’s eyes were closed, and there was a strange stillness about his figure that frightened her. She tried to force a spoonful of the hot milk between his lips, but the lips did not respond.

Frantically she ran to the telephone and called the doctor, rushed to the medicine cabinet, and brought smelling salts, but before she heard the doctor’s step at the door, inexperienced as she was, she was sure that her beloved father had left her.

They carried the precious form up to his room and laid it upon his bed. The doctor worked over him for hours, but the minister did not come back from the other world to which he had passed so swiftly and easily.

Kind friends came quickly in response to the doctor’s call. They wore startled faces and spoke gently to the minister’s white-faced daughter. They offered sympathy and comfort and wept because they had loved the minister. They tried to take Amorelle away to their homes—several of them tried—but the girl sat, white and silent, and shook her head. She even smiled at one dear woman.

“I couldn’t leave him!” she said. “Please don’t ask me.”

“But you cannot do anything more for him. He would want you to come away, I am sure,” urged the woman.

Amorelle shook her head.

“No. He wouldn’t,” she answered softly. “He would know how I would feel. He would know I would want to be here till the end. He knew he must go soon, even if he got well from this attack, and he often talked it over with me. Please, I could not go away.”

So they let her alone at last, all but a kind neighbor who insisted upon staying through the night. They were very kind people and were deeply shocked that the man who had brought them comfort and sympathy in all their distresses, who had borne with their whimsicalitites and criticisms and bickerings and strife, had slipped away so quietly without warning. They had not supposed his illness was serious. He had not wanted them to know. So they were sincere in their deep sorrow and tender with the young daughter left thus, alone in the world.

The next morning the city newspapers told the story. Her father’s face looking earnestly at her from the printed column with a notice of his death and a brief account of his life was like a blow to Amorelle. How had they known so soon? It seemed almost an intrusion, yet afterward when she summoned courage to read what they had printed, her heart throbbed with pride that he was rated so highly. Her quiet, unobtrusive father who had never sought honors was yet honored by those who had sometimes ignored him in his lifetime.

Then there came letters—flocks of them, troops of them. All the brother ministers in the vicinity wrote, telling how they honored him. Some of the names she recognized as those who had opposed him in presbytery in some move for deeper spirituality, who had playfully laughed at him as being a little fanatical. Yet they honored him now. She could read the sincere appreciation of his strong, true character even between the polite phrases that they felt it incumbent upon them to write.

Telegrams of sympathy poured down upon her from men high in office in his denomination, from college presidents, from scholars, and especially from several great spiritual leaders. It almost overwhelmed her and brought sudden tears of joy to her eyes. Not that it mattered what the great of the earth thought about him, but yet it comforted her that his worth and integrity had been recognized by his contemporaries.

The strange days before the funeral dragged by relentlessly; sad decisions to be made, terrible questions cropping up that seemed so out of place at a time like this and yet were a part of the whole cruel business of dying.

There came a message the second day after her father’s death from her uncle Enoch, her father’s brother.

I mourn with you in your great loss which is also my own. Deeply regret an injury to my knee will prevent my being with you at the funeral. We want you to plan to come at once to us and make your home here at least for the present. Let us know when to expect you.

Uncle Enoch

Amorelle looked at the message with a sad little smile and thought how pleased her father would be that this message had come. He was very fond of his brother, though they had been separated for years. But he had been sure that Uncle Enoch would stand by her when the shock of his death should come.

She put the message away in her bureau drawer. It was good to know that there was a place to go, but there was an unknown quantity to deal with in the shape of a strange new step-aunt and cousin whom she had never seen, a recent second marriage after Uncle Enoch had been a widower for years. She shrank from the unfamiliar contact. Aunt Clara, in her few brief messages, had impressed her as a worldly woman, perhaps a selfish one. However, that was a question that would have to be dealt with afterward. So she laid the message out of sight and tried to put it out of mind while she went alone with God through the hard days that were before her.

There were many who came to offer loving sympathy, but of course it was hard to meet even the ones whom she and her father had always loved. Again and again she had to retreat to her room and kneel beside her bed for strength to go on. It would be so much easier if she could have died, too, she thought.

There were kindly, well-meant offers to do shopping for her. Shopping! What would one want of shopping now? What did anything matter now, with her world gone into twilight? “No thank you, no shopping,” she said sadly, trying to keep the astonishment out of her voice.

“But surely you’ll want a black dress and hat!” they said.

“Oh, no,” she said quickly, “my father did not like the idea of putting on black because a dear one had gone to heaven. He would not want me to dress in black for him. I’ll just wear this brown dress and hat. He liked them, and they’re almost new. Oh, I’d rather not think about clothes now, if you please!”

They shook their heads sadly and said she was odd. Of course her father had been a little bit odd, too. But a young girl, one would think she would want to look like other people.

She did not choose the notables and the great of his denomination to conduct the service. She rather chose a plain, obscure man who had been his closest friend in that area, a man who would speak about the coming of the Lord Jesus when He will bring with Him the dead in Christ. She wanted a joyous note in the service, and she asked for his favorite song to be sung. The officials in the church had to plan a few extra items in the service to get in all the dignitaries their church pride demanded for a minister who had served their congregation these many years. Amorelle submitted to their wishes, for she did not wish to argue, but she did not like these things. She knew her father would not have liked them. But she also knew he would not oppose anything so nonessential.

So at last the service was over, and his tired, overworked body was laid to rest under the shadow of the church he had served for over twenty-five years; and Amorelle went back to the manse, which kind, skillful hands had made so immaculate and so desolate. A home that was no longer a home. A home with the heart of home gone forever from this earth.

Hannah prepared a nice little supper and tried to make the dining room look cheerful. There were delicate dishes sent in by loving friends and neighbors, but they could not tempt her appetite. Life had become a vast blank. She tried to grasp at the hope and help that her father’s advice had left her in the precious days while he was yet with her, when he tried to prepare her for this blank, but somehow her mind was numb. Perhaps she would be able sometime again to think and reason with herself, but as yet there was only one thing her father had taught her that she could remember and grasp, and that was that God was her refuge and strength. She couldn’t see the refuge, she couldn’t feel the strength, but she knew it was there, and she trusted in it.

But Hannah was suddenly sent for to attend her sister who had developed pneumonia. She went away, expecting the same neighbors who had stayed the night before to come again to be with Amorelle, but they, in turn, understood someone else was to be there. And so the girl was left alone in the house that seemed so silent and empty, and for the first time since her father’s death, she was absolutely by herself.

She was secretly relieved not to be under watchful eyes. Everyone had been so kind, and there had been someone continually with her. There had been no chance even to weep. Indeed she had scarcely shed a tear. So now, knowing that she was all alone, she went up to her room in the darkness and flung herself across her bed, letting her desolation sweep over her.

Then for the first time the tears had their way, breaking in a healing flood over her exhausted young soul.

It seemed a long time that she lay there, sobbing into her pillow, feeling that all the waves and billows of life had gone over her and left her alone, forgotten on the shores of life. And then like a faraway echo of her dear father’s voice, there came to her words that he had so often of late repeated to her when they were sitting together at twilight, or when he was lying on his bed during his illness.

Fear thou not; for I am with thee: be not dismayed; for I am thy God….I the LORD thy God will hold thy right hand, saying unto thee, Fear not; I will help thee.

And so, resting on the promises that she knew would never fail her, she sank to sleep at last.

It was bright morning when she woke, a trifle later than usual. She had been aroused by the sound of footsteps coming up the path to the house. Had Hannah come back? She sprang up quickly, flung on some garments, and rushed downstairs.

Chapter 2

Amorelle unlocked the front door of the manse, threw it open, and the spring sunshine flooded in and fell across the hall floor. It startled her to see that the sun could shine brightly in a world that had become so dark to her. It was almost like a blow, that sunshine going on just as if nothing had happened.

But Amorelle had no time to consider, for Mrs. Brisbane stood on the front porch, a plate covered with a napkin in her hand, her eager little gimlet eyes boring into the girl’s consciousness uncomfortably.

“Good morning. Am’relle,” she said, stepping into the hall with assurance. “I just thought I’d run over and see how you got through the night. Did you sleep much? I don’t believe you did. You look kinda peaked.”

“Oh, I’m all right, thank you, Mrs. Brisbane,” said Amorelle, summoning a wan smile. “Yes, I think I slept some.”

“Well, I suppose you’re not to be blamed for grieving. Your pa certainly was a good man, but you’ve got your own life to live, you know, and it don’t do to give way to one’s feelings. Your pa certainly wouldn’t have wanted you to do that. He was a sensible man, a very sensible man. I always said that about him, even though he didn’t have very good health recently. And then you’ve got to think of his gain, you know. He’s passed to his reward, and you wouldn’t want to bring him back, you know, into this world of sin and misery.”

Amorelle’s lip quivered suddenly, and she caught her breath in a quick way that was almost like a sob as Mrs. Brisbane’s pious tone swept ruthlessly over her sensitive consciousness. Then she set her lips in a firm, controlled line.

“Won’t you sit down, Mrs. Brisbane,” she said politely, motioning toward the shabby manse parlor. “It was very kind of you to come and inquire. But I’m quite all right, thank you.”

“Well, I always said you were a brave girl,” said the caller, giving her another searching glance as if still hoping to find some evidence of weakness. “Yes, I’ll sit down for just a minute, but I can’t stay. I’m putting up crab apples today, and I must get at it. But I just thought I’d run over and see if you were all right, and I brought you just a taste of hot biscuits I made for breakfast this morning. Have you had your breakfast yet?”

“Oh, that’s very nice of you, Mrs. Brisbane,” said Amorelle, trying to make her voice sound steady. “No, I haven’t had my breakfast yet. I didn’t seem to feel hungry. But perhaps this will help me to eat.”

She took the little plate offered graciously and lifted one corner of the napkin, trying to look interested.

“Oh, they smell delicious! You do make such wonderful biscuits always. It was very kind of you to think of me.”

“Well, I didn’t think Hannah would likely bother to make anything hot for your breakfast, so I thought I’d just run over with these,” said Mrs. Brisbane with a gratified tone to her voice. “Hannah never was one to make hot breads much, was she? Has she got your breakfast ready? Why don’t you call her to put these where they’ll keep hot till you sit down?”

“Why, Hannah isn’t here this morning, Mrs. Brisbane. Her sister was taken very sick last night with pneumonia and they came for Hannah to nurse her!”

“And she went off like that and left you all alone in the house! The first night after a funeral! Well, upon my word! And who stayed with you?”

“Oh, I didn’t need anybody to stay with me,” smiled Amorelle wanly. “I wasn’t afraid.”

“Well, but that wasn’t hardly respectable!” said Mrs. Brisbane indignantly. “I’m surprised at Hannah!”

“Oh, Hannah wasn’t to blame,” said Amorelle. “She was distressed about leaving me, but I told her there were plenty of people I could call upon, and she mustn’t think of such a thing as waiting a minute. But I really was all right, Mrs. Brisbane. I rather wanted to be alone and quiet just for a little.”

“Well, it isn’t good for you, and it mustn’t happen again. You’ll just come over to our house to sleep tonight. I won’t hear to anything else.”

“You are very kind,” murmured Amorelle with a troubled look in her eyes. “I’m not just sure what I’m going to do yet. I appreciate your invitation, but I think perhaps Hannah may be back tonight. She thought her sister from Barlow might be over to take her place. It really isn’t worthwhile for me to bother anybody else. I’m just as well off here, and I’ll be having plenty to do.”

Mrs. Brisbane’s sharp eyes went around the room surprisingly.

“Yes, I suppose there will be plenty to do, but you’ll hardly know how to go about it, will you? Didn’t I hear your father had a brother?”

“Yes, Uncle Enoch. He lives in the West.”

“Strange he wasn’t here at the funeral.” The sharp eyes searched the girl’s sensitive face.

“Why, he had a sprained knee,” explained the girl, “and wasn’t able to travel. He telegraphed. He said I was to come on and visit them for a while.”

“H’m!” said the caller. “He has a family then. One would have supposed some of them would have come to the funeral. His only brother! It would only have been decent.”

“Well, you see, Aunt Clara is Uncle Enoch’s second wife. We don’t know her very well. I don’t suppose she would have thought it necessary. My Aunt Jean, Uncle Enoch’s first wife, died over ten years ago.”

“Weren’t there any children?”

“Aunt Clara has a daughter, by her first husband. She’s a girl about my age.”

“H’m! That don’t sound so good for you. Didn’t your Aunt Clara write, too, inviting you?”

“Not yet,” said Amorelle wearily. “She’s scarcely had time.”

“Well, are you intending to go?”

“Oh, I’m not sure what I’ll do,” said the girl, passing a frail hand over her eyes. “You know I really haven’t had time to think anything about it.”

“It’s an awful pity you couldn’t just stay here,” said the visitor, looking around the room speculatively. “If they should get a young minister, and he should be unmarried, it might be just natural for him to take to you, and then you could just stay here and the manse would be all furnished. It would be a real godsend to a poor, young minister.”

“Oh mercy! Mrs. Brisbane, please don’t talk like that!” said Amorelle desperately.

“Why, why shouldn’t I, child? It would be a perfectly natural thing for a young minister to marry a minister’s daughter, and so economical, too—save moving and buying furniture. I heard some folks talking down at the Ladies’ Aid the other day, the day your father died. They said if anything happened to him, they thought we ought to have a young minister next time. A change was a good thing. And some of them mentioned that Mr. Cole that’s been holding evangelistic services over at Claxton Center. They do say he’s open for a church, and he’s real spiritual for a young man. Of course, he’s lame in one leg, but you wouldn’t mind a little thing like that. Only some said they thought he was already engaged. Only, of course, engaged isn’t married, and there’s many a slip.”

“Oh, Mrs. Brisbane! Please,” pleaded Amorelle. “Please don’t say such things, even in fun.”

“Why, I don’t see why you feel like that!” said the woman, looking at the girl’s troubled face in astonishment. “I’m only suggesting it would be awfully convenient if things would fall out that way. You know you’d really be a lot happier if you were married. That’s a girl’s natural lot, and there’s nothing to be ashamed of about it. I said last night to Mr. Brisbane that it’s a pity some well-fixed bachelor here in the town didn’t come forward and marry you. At a time like this, you being all broke up this way, it wouldn’t be necessary to be formal and wait a long time. It would only be kind to get things settled up for you. I said to Mr. Brisbane, I said, ‘And I presume they would, only Amorelle’s always been so choosey, never really going with any of the young men, just good friends with all.’ It really wasn’t called for, Amorelle. You weren’t the minister, and you had your own life to live. I always said it wasn’t right you shouldn’t have had any beaux. Your father ought to have had more forethought.”

Amorelle fairly quailed before this avalanche of opinion. But when her caller reached the point of criticizing her beloved father so recently separated from her, her eyes flashed indignantly.

“Mrs. Brisbane,” she said with a gentle dignity, “that’s enough! Too much! I don’t want to get married! And I don’t want to hear about it now, either.”

“Oh now, Amorelle, don’t be foolish! You’ve got your future to consider, and there’s nothing immodest in a girl discussing the possibilities of her marriage. I’m only being kind to you, saying what your own mother might say if she were here. And I say that if some well-fixed young man should come forward and offer to marry you, I think you should accept him. I think the whole parish would bear me out in feeling that way. And there’s plenty here could do it, too. There’s Carson Emmons. His wife’s been dead a good year and he’s had seven different housekeepers. It really would be to his advantage to get a good wife. You’d make a good mother for his poor little, peaked twins, and you’d run his house much more economically than any housekeeper. And see how well you’d be fixed. A nice two-story house on the edge of town and a new car and everything!”

“Oh, Mrs. Brisbane!” Amorelle’s face was the picture of disgust, but it was no hindrance to the voluble woman.

“No, now, Amorelle, don’t be so modest. It’s perfectly right what I’m telling you. I haven’t a bit of doubt that if Carson Emmons thought you’d accept him, he’d come running. He just needs some good mother to talk to him, and I wouldn’t mind being the one!”

“Mrs. Brisbane!” There was horror in Amorelle’s tone now.

“No, I wouldn’t!” went on the caller, now thoroughly started on a campaign for the good of her minister’s orphaned daughter. Mrs. Brisbane loved to set the world right. She felt she had a gift at that sort of thing. “And there’s several other in our church and community that I could suggest, too. There’s Mr. Merchant! A big house and grounds, a good business, and he a nice, kind bachelor! His wife would have everything easy. Of course he’s a bit older than you are, but what are years in a case like that where people are well fixed? Of course his mother is living yet, but she’s just on the edge of the grave, so to speak, and it wouldn’t be long till you had everything just as you wanted it. I know Mr. Merchant real well. I wouldn’t mind putting a bug in his ear.”

“Listen, Mrs. Brisbane,” said Amorelle, whirling around from the window where she had been staring blindly out, trying to conquer her temper, “if you ever dared say a word like that to any man, I should be so angry I would never want to see you again. I feel as if I could never hold up my head and go around the town again after you have made such suggestions.”

“Oh, now don’t be silly, Amorelle! I wouldn’t say anything you would mind. I’d just kid ’em along. You know me. Why, child, there’s plenty in town would just jump at the chance to marry you, and that would settle all your troubles in no time and just fix you for life. There’s that Johnny Brewster! A clean, fine fellow, everybody says. Got a nice grocery business going, doing well. He owns the building, and there’s a nice little apartment over it you could live in. Course Johnny’s young, but I guess at that he isn’t more’n a year or two younger than you are, and he’s real well and hearty and sensible. Only thing, he hasn’t been to college, but you’ve got learning enough for two, and anyway, in your position you can’t afford to stop on a little thing like that!”

Amorelle dropped into a chair weakly and looked at her caller helplessly, on the verge of hysterical laughter. How could she stop that awful tongue? She felt so humiliated it seemed as if she never could hold up her head again. But the clattery tongue went right on.

“And then there’s Mr. Pike! He really needs to get married! His hair is beginning to get thin on the top. And they do say he’s got plenty of money stowed away!”

Amorelle suddenly rose from the chair, her face white with anger, trembling from head to foot.

“Mrs. Brisbane,” she said, “we will please talk about something else. I do not wish to hear anything more about marriage! I do not intend to marry anybody at present, and particularly not any of those men you have mentioned. You may intend kindness, but you make me very angry, and if you say another such word I shall go out of the house and leave you by yourself.”

“Hoighty toighty!” laughed Mrs. Brisbane. “A tempest in a teapot! I thought they said you were such a good Christian! Well, if you’re so set against marrying, what are you going to do? You might teach school, but all the positions in town are filled for another year, and you wouldn’t stand a chance out of your own county where you are known. It takes a lot of pull today to get in anywhere. You might teach music, I suppose,” she said with a speculative glance at the old upright piano, “only public opinion wouldn’t back you in taking pupils away from Miss Rucker, now that she’s lost her leg and couldn’t very well do anything else.”

“Really, Mrs. Brisbane, I don’t think you need worry about me. I shall find my place somewhere,” said Amorelle, trying to steady her voice.

“Well, I think it’s our call to worry about you,” said Mrs. Brisbane virtuously. “You’re our pastor’s daughter, and of course we feel we must see you into some safe harbor. What are you going to do about your furniture? You can’t take that to your uncle’s with you. It would cost too much to ship it so far. I suppose you’ll have to sell it. The ladies were talking about it the other day. They seemed to think it might be possible for them to buy a few things from you. Mrs. Woods spoke about that walnut bedroom set up in the front room. They were talking about furnishing a couple of the rooms in the manse. You know it used to be quite the thing to have a manse ready furnished. They spoke about your father’s library. His books likely would be a great help to a young minister just out of seminary. I think some of the Ladies’ Aid are coming in this afternoon—no, I believe it’s tomorrow they’re coming—to put a price on the things they are willing to buy for the manse. Of course they couldn’t give much, but you’d want to help out with your father’s old church, and it would really be a blessing to you to get things off your hands. Especially a lot of theological books.”

Amorelle gave a cold, startled look at her caller.

“Oh, I couldn’t give up the books,” she said with decision. “I wouldn’t part with them for anything.”

“For heaven’s sake, why not?” demanded the woman calmly. “That’s foolish, Amorelle. What could you do with a lot of books, carting them over the country? Your uncle certainly wouldn’t want to pay cartage for them, and you haven’t any way to pay storage.”

“I haven’t made my plans yet, Mrs. Brisbane,” said Amorelle with reserve. “There will be a way for everything.”

“Well, of course you haven’t had much time to plan with your father scarcely cold in his grave yet,” assented the woman calmly, “but that’s why I came in this morning to say we are willing and glad to help. I don’t suppose you’ve got any money, have you?”

The color swept up into the girl’s pale cheeks and over her white forehead into her hair. Her sweet dignity was astonishing.

“I think—I’ll manage—Mrs. Brisbane! We haven’t any debts, at least.”

“Well, that’s one good thing; your father always was honest, if he wasn’t very provident. It does seem as if out of his salary, with only you to keep, he might have put by a tidy sum. I’ve known ministers with less than he had to have managed a good, big life insurance, or bonds or something. But then your father never had his mind much on the things of this world, and I suppose in a way that’s a credit to him, but somehow it doesn’t help out in paying bills. How about the undertaker? Are you figuring to pay him or were you expecting the church to pay that?”

“Certainly I shall pay it!” said Amorelle. She felt cold and numb now to her fingertips.

“Well, that’s good if you can do that. Of course the church expects to do something. I don’t know just what. I heard the men talking at prayer meeting the other night. They might give you a month’s salary if there aren’t too many bills left to be paid. That’s what the people did for the widow of Reverend Salisbury over at Greenwich last winter. One month’s salary clear! But then, you know your father was sick a good two months, and they had to get fill-in preachers as well as pay him. You’ve got to think of that, you know.”

“I’m not expecting anything from the church, Mrs. Brisbane. I would much rather they didn’t do anything for me. I’ll be all right.”

“Oh well, they’ll do something. I don’t know what it’ll be. But it’ll be something nice, of course. Our church always does the right thing, and they really thought an awful lot of your father. Of course if they decide to buy your things, why that’ll count some. It’s the Ladies’ Aid really that’s thinking of them.”

“Mrs. Brisbane, I wish you would ask them not to worry about me.” Amorelle was trying to speak pleasantly, almost cheerily. “There really isn’t any need for anybody to worry about me. I shall soon have my plans made now and get my things out of the manse.”

“Well, yes, of course you wouldn’t want to hold up the work of getting ready the place for the next minister,” admitted Mrs. Brisbane, rising with a deprecatory look around. “The paint looks pretty well worn off the doors and window sills, doesn’t it? Wasn’t that just painted last season? Seems as if it ought to have lasted longer than that, doesn’t it? What kind of soap do you use?”

Amorelle’s desperation was suddenly relieved by the sharp ring of the manse doorbell.

“Mercy! Who’s that?” said Mrs. Brisbane, whirling around to peer out from behind the faded, old chenille curtain, through the glass at the side of the front door. “Oh, it’s Mrs. Spicer. She’s got something in a covered dish. It’s likely one of her Spanish omelettes. She thinks everybody appreciates them as much as she does. For my part I think an omelette ought to be eaten piping hot off the skillet and not steam in a dish all the way across the road. Well, Amorelle, I’ll just slip out through the kitchen door. I really haven’t time to stop and talk. Mrs. Spicer is so long winded. I’ll just slip those biscuits onto another plate as I go through and save you the trouble of bringing back the plate and napkin. Good-bye, child! I’ll be over to help you bright and early tomorrow. Don’t you worry about one thing. I’m going to have you right on my mind all the time!”

Mrs. Brisbane timed her sentence exactly to make the last syllable audible in the hall before the front door opened and she vanished into the dining room, where she slid her biscuits upon a china plate from the corner cupboard, gave an appraising glance around at the immaculate room, and hurried on through, missing not one thing in the kitchen as she unbolted the back door.

Mrs. Spicer was a thin, little old lady with water-faded eyes, crumpled parchment skin, and the palsy. She wore a small perennial shoulder shawl of Scotch plaid, and there was a pitiful shake to her head as she spoke. She held in her shaking hands a covered silver dish, and there was a gentle whine in her voice.

“Oh, good morning, Amorelle”—she quivered—“You poor little lonely thing. I’ve just been having you on my heart all night!” Her voice quavered into a sob, and the tears rained down wetly as she managed a feeble little arm around the girl’s reluctant neck and drew her into a damp embrace.

Amorelle wondered, as she struggled against the overpowering gloom, why it displeased her so to have this dear, little old lady weep. It was wicked of her, of course, to resent other people crying for her.

“It’s very dear of you to think of me,” she said, trying to speak cheerily. “Won’t you come in and sit down?”

The old lady tottered gently in and sank into the upholstered chair by the door, almost upsetting the steaming dish she carried.

Amorelle rescued the dish.

“Shall I set this down for you?’ she asked pleasantly.

“Why, yes, if you will. It’s just some of my Spanish omelette. Most folks like it, and I thought it would be tasty for your breakfast. That is if I’m not too late? You haven’t eaten your breakfast yet, have you?”

“Oh, no, Mrs. Spicer, I slept late this morning. That’s very kind of you to think of me.”

“Well, I’ve just been bearing you on my heart all night,” said the good woman, letting loose the tears again. “I expect you didn’t sleep a mite all night. I expect you just cried your heart out!”

“No, Mrs. Spicer,” said Amorelle quietly. “I didn’t cry much. Of course I’m going to miss my father desperately, but we talked about his going to heaven. He didn’t want me to grieve. He wanted me to think of the time when we shall all be together again. By and by. He wanted me to be brave and trust God and live out whatever God had for me to do. Of course it’s terribly hard, but I’m glad for him, joyously glad. You know he suffered greatly those last few months.”

Amorelle brushed away a bright tear and tried to smile into the watery old eyes, and the old lady stared at her in wonder.

“Well, it’s very wonderful if you can feel that way,” she murmured, “but weak human flesh falters. Death is such a final thing! And you and your father were always so close. I know you must feel it intensely.”

She got out a black-bordered handkerchief and wiped her eyes.

“One doesn’t get over those things! I always say death is so final, so inevitable. I grieve as much today over my sainted husband as I did the day he died, and that’s nearly twenty years ago.”

“Yes, it’s very hard to face,” said Amorelle with a quiver of her lip, “but I promised Father I wouldn’t give up to grief and I’m going to try to keep my promise. You know, when you realize that the Lord Jesus has conquered death, there is no more terror in it. The parting is hard, but we who believe do not have to sorrow as others who have no hope. We’ll all be at home together someday. Mrs. Spicer, there are sometimes things harder to face than death.”

The old lady stared uncomprehendingly at her.

“Yes, I suppose it is so,” she assented with a sniff. “But I have always felt keenly the fact that I didn’t have a home of my own. It was through no fault of Mr. Spicer’s, either. It was all through the machinations of a man who borrowed money from him under false pretenses. A man who lives right here in this village. He was a mere boy when it happened, but he was a slick one. He’s old now, but he’s still slick. His name is Pike. I’m sure I hope others will be saved from his grasp. And you, Amorelle, poor child, you haven’t any home either, have you? Oh, if I had a home of my own I’d invite you right home to live with me as long as you would stay. But you know it’s not the same when you’re living in your son-in-law’s house. You don’t feel free. But, poor child, what will you do?”

“I’m not sure yet,” said Amorelle reservedly. “My uncle has invited me to come to him. I haven’t got my bearings yet, but I’ll know soon, and I’ll let you know my plans before I go away anyway. I certainly do appreciate your kind thought of me. Now, would you like me to empty this pretty dish right away? You may need if for the next meal.”

“Well, if you don’t mind,” said Mrs. Spicer, rising reluctantly. “Nobody knows I brought that silver dish. They might miss it.”

Amorelle slipped the sinking omelette into another dish and hurried back to her caller, who was standing in the hall now, looking back into the study where the door stood open.

“And that was your father’s study!” said Mrs. Spicer with a sob in her voice. “Oh, I can see him sitting there in his big chair at the desk now. Such a holy man he was!”