Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow Ltd

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

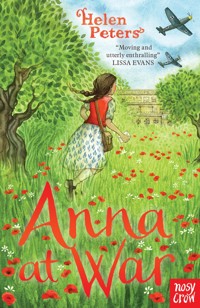

"Moving and utterly enthralling" - Lissa Evans As life for German Jews becomes increasingly perilous, Anna's parents put her on a train leaving for England. But the war follows her to Kent, and soon Anna finds herself caught up in a web of betrayal and secrecy. How can she prove whose side she's on when she can't tell anyone the truth? But actions speak louder than words, and Anna has a dangerous plan... A brilliant and moving wartime adventure from the author of Evie's Ghost. Cover illustration by Daniela Terrazzini. "Because I believed in Anna, her war came alive for me. Her struggle, her bravery, all those things were completely real and I read the book overnight, unable to put it down. Magnificent, brilliant, heartbreaking." - Fleur Hitchcock, author of Murder in Midwinter "A fast-paced adventure, whose elegant prose and cliffhanger chapters should keep even less confident readers gripped to the thrilling end." - Emily Bearn, Daily Telegaph "It's a tale of bravery and loss that Helen Peters (Evie's Ghost) sets out with the light touch that only rigorous research allow... Peters tells Anna's story of escape with great humanity, and this novel is an excellent way to whet young appetites for classics such as When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit by Judith Kerr and Carrie's War by Nina Bawden." - Alex O'Connell, The Times, Children's Book of the Week "Anna at War is a gripping, moving piece of historical fiction." - Imogen Russell Williams, Guardian "Helen Peters balances adventure and intrigue with this emotional coming-of-age story." - Emma Dunn and Sarah Mallon, Scotsman

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 325

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For all the children who have had to leave their homes and make new lives in other places

CHAPTER ONE

A Letter From the Secret Service

It was Mr Harte who started it all.

“We’re going to be learning about World War Two,” he told us on our first day in Year 6.

Everyone was excited, especially Jacob and Murphy, who actually cheered. They’re obsessed with war, those two.

“Do any of you know anyone who lived through the Second World War?” Mr Harte asked.

I put my hand up, and so did a few other people. Mr Harte looked around the classroom and his eyes came to rest on me.

“Yes, Daniel?”

“My granny,” I said. “She came over from Germany just before the war started.”

“That’s so interesting. Did your granny come to England as a refugee?”

“I think so,” I said, feeling embarrassed now, because actually I wasn’t sure. Granny didn’t seem like a refugee to me.

Other people started asking questions.

“How old was she when she came to England?”

“I’m not sure.”

“Was she a Nazi?”

“Of course she wasn’t. She’s really nice.”

But that was the only thing I was sure about. The more questions they asked, the more I realised I didn’t really know anything about Granny’s childhood. I knew she left Germany to get away from Hitler, but anyone would want to get away from Hitler, wouldn’t they? So I’d never asked any more questions. I’d always had the feeling that I shouldn’t ask.

But now I really wanted to know more.

I decided to visit Granny on my way home. I often call in after school on a Wednesday. It’s the only afternoon she isn’t busy. Granny’s eighty-nine years old, but she seems a lot younger.

“You have to keep active,” she always says. “There’s too much to do to sit around wasting time.” So she goes on a two-mile walk with friends every morning, “to stop me seizing up”. She also spends a lot of time working with a charity that helps refugees to settle in England, and she belongs to lots of clubs in the village, so she’s hardly ever at home in the daytime.

I love going to Granny’s. She’s always pleased to see me and, as soon as I arrive, she puts the kettle on for tea and gets out the chocolate biscuits.

That afternoon was lovely and sunny, so we took the tea tray out to the garden table. As soon as Granny sat down, Inka, her black-and-white cat, jumped up on to her lap.

Inka came from a rescue centre, and she adores Granny. I do like cats, but Inka is quite annoying. It would be fine if she just sat there, but instead she walks round and round on Granny’s lap, miaowing really loudly, and then she starts clawing at Granny’s clothes and sneezing all over her hands. I don’t know how Granny stands it, but she’s incredibly patient. She says Inka was probably taken away from her mother too early, so she has separation issues that make her needy and anxious.

I was waiting for Inka to settle down, and wondering how to bring up the topic of Granny’s childhood, when she kind of did it for me.

“What are you doing at school at the moment?” she asked.

“We’ve just started learning about the Second World War,” I said, taking a chocolate biscuit from the plate.

Granny reached for a teaspoon. “Oh?”

I took my chance.

“Mr Harte asked if any of us had relatives who were alive then. So I told him you came over from Germany just before the war.”

Granny slowly stirred her tea. Her eyes were fixed on the blue and white mug.

“Everyone was really interested,” I said. “They had lots of questions about it. But I didn’t really know anything else.”

Granny stayed silent for a minute. Then she said, “How strange that you should say that today.”

“Is it? Why?”

“Such an odd coincidence.”

“Why?” I asked again.

She raised her eyes from her mug and looked at me.

“I had a letter this morning. Completely out of the blue. From MI5.”

I stared at her. “MI5? The spy agency?”

“That’s right. The Secret Service. They’re planning to release my Second World War files, and they’re asking if I wish to remain anonymous or if I want to have my name and picture published.”

I was baffled.

“Your Second World War files? Why does the Secret Service have files on you? You were only a child in the war, weren’t you?”

“I was twelve when I came to England. But when all this happened, in 1940, I was thirteen.”

“When what happened? When MI5 were spying on you? So did they spy on all Germans? Even children?”

Granny paused. “Not exactly.” Then she gave me a mischievous, twinkly-eyed smile. “Well, not at all, in fact. No. They weren’t spying on me.”

“So why do they have files on you?”

Granny was silent for a very long time. Her eyes gazed across the garden, but she wasn’t looking at the flowers, or the village street, or even the hills beyond. She was looking much further into the distance than that.

Just when I was beginning to think she might never speak again, she turned to look at me.

“Do you really want to know about it?”

“Yes,” I said. “I really do.”

Granny looked at me thoughtfully. “It feels right that I should tell you now, when you’re almost the same age as I was when it all started.”

“So what happened?” I asked impatiently.

She smiled. “I need to find some things first. Can you wait a few days?”

“Sure,” I said, though I was a bit disappointed. I was bursting with curiosity since she’d mentioned MI5.

“How about Sunday? I should be ready by then.”

Ready for what? I wondered. But I didn’t ask any more questions. We talked about other things until I’d finished all the biscuits and it was time to go home.

When I went round to Granny’s on Sunday, there was a box I hadn’t seen before lying open on the living-room table. There were lots of old letters in it, and a faded notebook. Next to the box sat a framed black-and-white photo of a man in a shirt and trousers, and a woman in a flower-patterned dress. They both had kind, gentle faces. He had his arm around her shoulders and they were smiling at the camera.

I had seen the photo before. It normally sat on Granny’s bedside table. Once, when I was younger, I asked her who the people were. She said they were her parents, but there was something in the way she said it that meant I didn’t ask any more questions.

I had no idea what to expect when I sat down with Granny that afternoon, armed with Mum’s phone to record our conversation.

I certainly didn’t expect the story I heard. And I also didn’t expect it to give me an idea for Granny’s ninetieth birthday present.

Mum had been worrying about what to get Granny for her ninetieth birthday. There didn’t seem to be anything she really wanted. But Granny’s story gave me an idea. The best idea for a present I’ve ever had.

Granny seemed to take longer than usual making the tea that day. When I carried in the tray and we sat down, she told me she had never really talked about her childhood before. Not even to her own children. Some parts of it had been too painful to remember, she said. Other parts had been top secret.

“But now I want you to hear it. There aren’t too many of us left, and it would be a shame if our stories died with us.”

So here it is, in her own words. The extraordinary wartime story of my grandmother, Anna Schlesinger.

CHAPTER TWO

Open Up!

I shall never forget the night my life changed forever. It was the ninth of November, 1938, and Uncle Paul had come for supper.

They thought I was in bed, but I wasn’t. I was sitting on the hall floor, leaning against the living-room door, listening to every word they said.

Listening at the door was the only way to find out what was really going on. These days, my parents’ conversations always seemed to stop when I came into the room. I knew they were trying to protect me from the truth. As if that was possible.

So all through our supper with Uncle Paul, we talked cheerfully about nothing in particular. It was only now, after they had sent me off to bed, that they would speak honestly about the situation.

Uncle Paul was my favourite relative after Mama and Papa. He was Mama’s younger brother, and he was one of those people who could make everything fun, even something completely normal, like a walk to the shops. My parents were quite serious, so I always loved spending time with Paul.

But now, even Paul was leaving me. He was a doctor, but Hitler had said Jewish doctors weren’t allowed to treat non-Jews. Since there were hardly any Jewish families in our little town, Paul couldn’t afford to live here any more. And he had friends in Paris who said they could find him work there.

Even though I knew this, I was angry with him for deserting me. Everything in my world seemed to be falling apart. School was awful. The other children didn’t speak to me any more. Even my best friend Ingrid, who lived across the street, had stopped coming round to play.

“So that’s it,” said Mama. I heard the rattle of the coffee cups as she put them on the table. “Once you go tomorrow, we’ll be the only members of the family still in Germany.”

“And you need to get out too,” said Paul. “When are you going to wake up? You’re like ostriches, the pair of you, with your heads buried in the sand. You’re intelligent people, for goodness’ sake. I don’t understand it.”

“We’re not free-and-easy youngsters like you,” said Papa. “We can’t just get on a train with a rucksack on our backs. Where would we go? What would we do? I don’t want my family to be refugees in a foreign country, with no money and nowhere to live. I’m too old to start again. And how would I find work in a country where I don’t even speak the language?”

“Hans and Ruth found work in England,” said Paul.

“As servants! And then only because that cousin of Ruth’s in Manchester begged a favour from her rich neighbour. And Hans is a professor of law!”

“Was a professor of law,” said Uncle Paul, “until the Nazis took away his job.”

“He’s never even picked up a spade,” said Mama. “How on earth is he going to work as a gardener? With his bad back too. And Ruth employed as a cook, when she’s never made a meal in her life. They’ll be fired within a week, and then they’ll be homeless in a foreign country. What will happen to them then?”

“At least they won’t be here,” said Uncle Paul. “That’s the only thing that matters now.”

“It was different for them,” said Papa. “Hans can’t work here any more. But I have my own business.”

I heard Uncle Paul groan in frustration. “The Nazis are taking away Jewish businesses every day. You know what happened to Alfred’s shop. What makes you think you’re special?”

“Shops, yes,” said Papa, “but we’re a highly respected publishing house. The business has been in the family for three generations. They can’t take that away.”

“They can do whatever they want, and nobody lifts a finger to stop them. All the Polish Jews have already been deported. I don’t know why you think they won’t touch you.”

“We’re not Polish,” said Papa. “We’re German. We’ve been German for generations.”

“And you’re Jewish,” said Paul.

“But we’re not even religious,” said Mama.

Uncle Paul gave a bitter laugh. “And you think that will save you? You think Hitler’s thugs will spare you because you don’t go to synagogue? You’re a pair of idiots.”

My father never shouted. He went dangerously quiet instead. His voice was very quiet now.

“That’s enough, Paul,” he said. “You’ll wake Anna.”

I tensed, ready for a silent sprint to my room in case somebody decided to come and check on me. But it didn’t seem as though anyone was going to move. My mother spoke in a strained, quavery voice.

“Walter is a war hero. He won the Iron Cross. Even Hitler isn’t going to turn on war veterans.”

“I don’t understand you,” said Paul, and his voice was quiet and despairing now. “You do listen to the radio, don’t you? You have heard his speeches?”

I had heard his speeches, although my parents didn’t know that. They turned off the radio if I came into the room when he was speaking. So I listened from the hall instead.

Hitler never seemed to speak in a normal voice. He shouted and screamed, and he sounded completely mad. It was really frightening, especially when he ranted and raved about how the Jews were responsible for all the problems in Germany.

I couldn’t make sense of the world any more. Why was it such a terrible thing to be Jewish?

I tensed up. Harsh voices were shouting in the street. I heard glass smashing and then boots clattering down the road.

“There,” said Paul. “That’s your friendly, understanding Nazis, just having a bit of fun.”

“Let’s not argue any more,” said Mama. “This is the last time we’ll see you for who knows how long. Are you really taking Mitzi to France with you?”

Mitzi was Paul’s cat, a big, fluffy, black-and-white beauty. Paul adored her.

“Of course I am,” he said. “She likes train journeys. She’ll be happy in her basket.”

“Let’s have some music,” said Papa.

That was one of his favourite sentences. It was the cue for Mama to sit at the beautiful grand piano. Sometimes, if it was earlier in the evening, they would ask me to play for them too.

The dining chairs scraped back across the polished floor. I tried to spring to my feet, but my legs were stiff from crouching and I nearly fell over. I managed to steady myself and pad across the hall to my bedroom.

I lay awake for a while, listening to the music. It must have lulled me to sleep, because the next thing I remember is waking with a violent lurch of the stomach. Somebody was thumping on the front door of our apartment, and a man’s voice shouted, “Open up! Open up now!”

CHAPTER THREE

The Night of Broken Glass

“Open up!” barked the voice again.

Something heavy smashed against the front door.

My bedroom door creaked open. My stomach knotted in terror.

“Anna,” whispered Mama, pulling back the bedclothes. “Get in the wardrobe, quick.”

More smashing on the door, and men’s voices swearing.

“What’s happening?” I tried to say, but my throat was closed up and no words came out.

“In the wardrobe,” Mama whispered urgently. She was half-pushing, half-carrying me across the room. She swept the clothes to one side and bundled me into the wardrobe, pulling the hangers back across so the clothes hid me. It was even darker than the room. My heart hammered in my chest.

Another tremendous smash. Harsh voices shouting inside our apartment.

Was that Papa’s voice speaking to them? It was hard to tell over the shouting.

Where was Mama? Was she hiding, too?

More smashing and crashing. It sounded like china and glass.

A scream. Mama!

Her scream stopped abruptly, as though someone had clapped a hand over her mouth. Glass shattered; crockery smashed; men shouted; doors banged; piano keys crashed; wood cracked and splintered.

My bedroom door opened. Light appeared around the edges of the wardrobe doors. Someone had switched the light on. Who?

Smashing, tearing, stabbing.

With trembling hands, I parted the dresses and peeped through the narrow gap between the wardrobe doors.

No!

Two Nazi storm troopers were destroying my room. One man stabbed through my bedclothes with a bayonet, slashing at the mattress and the pillow. I turned ice-cold. Would he have done that if I had still been in the bed?

The other one had an axe. He pulled out the drawers from my chest of drawers and tipped my clothes all over the floor. Then he swung his axe up high and brought it down on one of the drawers over and over again, smashing it to pieces.

Over there was my bookcase, filled with picture books I’d had since I was a baby and storybooks I read again and again. Would he destroy them next? Or would he come for the wardrobe?

The other man was slashing my bedclothes to shreds.

Oh, no!

I almost let out a shriek, but I clamped my mouth shut just in time.

Alfred, the teddy bear I’d slept with every night of my life, lay in the bed right next to my pillow.

Leave him alone, I silently screamed. Leave him alone!

The man with the axe kicked the final drawer hard with his shiny boot. The sides collapsed on to the floor. He turned to face the wardrobe.

I stopped breathing. I shrank back, pressing myself against the wood.

A scream. A wild, unearthly scream.

I looked through the crack in the doors. Mama ran into the room, her hair dishevelled, her face bright red and distorted with fear and rage. She shoved the man aside and sprang to the wardrobe, pressing herself in front of it, blocking my view.

“Leave it!” she cried. “Leave it alone! There’s a child in there.”

I heard a scuffle and my mother’s cry as the man pushed her aside. The wardrobe doors were wrenched open. He grabbed my arm and yanked me out. Mama pulled me away from him and dragged me into the hall.

“Put your shoes on. Quick,” she whispered.

I stuffed my feet into my shoes. I heard the men hacking the wardrobe to pieces. Mama grabbed our coats and we hurried out, stepping over the splinters of our smashed front door.

“Where’s Papa?” I asked, as we ran down the stairs. “Why isn’t he coming?”

Mama didn’t answer. A sick, cold feeling settled in my stomach.

“Mama? Where is he?”

She gripped my hand tighter. At the bottom of the stairs, she led me to the back door that opened into the shared garden of our apartment block. She unlocked the door and we ran to the garden shed. Mama pulled me inside and shut the door behind us. She cleared a space among the tools on the floor and we sat down, our backs against the wall. My heart was thumping against my ribs.

“What if they find us here?” I said.

Mama didn’t answer. She just hugged me tight.

I heard glass smashing on the street, and the tramping of boots in the road behind our garden. What would happen if they burst into the shed? I couldn’t think about that. I screwed my eyes shut. The world behind my eyelids flashed red and black with terror.

“Where’s Papa?” I said, through my half-closed throat. “Is he…?”

I couldn’t say the word, but she knew what I meant.

“No,” she said. “No, Anna. He’s just had to go away for a while, that’s all.”

“They took him away?”

“Yes.” I could tell she was trying not to cry.

“Where?”

She shook her head. “I don’t know. We’ll find out. Don’t worry, darling.”

How could she tell me not to worry?

We sat there in silence, listening to tramping boots, shouting and destruction. I tried just to listen and not to think. I couldn’t let myself think.

Eventually the boots faded into the distance. “Come on,” said Mama. “Let’s go indoors.”

“No!” I said, a picture of our shattered apartment flooding my mind’s eye. “I’m not going back.”

Mama took a deep breath. “Where else would we go?”

“What if they’re lying in wait for us?”

“They’ve all gone now. And maybe Papa’s back.”

I hadn’t thought of that. If Papa came home and found the apartment empty, he would be so worried.

I could hardly stand up, I was so stiff from the cold and sitting for hours on the floor.

When we got into the apartment, I called, “Papa! Papa!”

No reply. Where was he? What were they doing to him?

Panic overwhelmed me. My throat closed up and I thought I was going to choke. Mama put her arms around me.

“Stay strong, Anna,” she said. “We must stay strong for Papa. You need to sleep now.”

I refused to go to bed until we’d searched the whole apartment. Shards of glass from picture frames and ornaments crunched beneath our shoes. The piano was smashed to splinters. The kitchen floor was littered with pieces of Mama’s wedding china. But there was nobody there. And they hadn’t hurt Alfred. They had knocked my bookcase to the floor, but they hadn’t actually destroyed the books. I set the bookcase upright and started to put the poor books back.

“You need to go to bed, Anna,” said Mama. “You can sleep in my room.”

“I have to put these back first,” I said, panic rising inside me. I couldn’t bear to see them spilled all over the floor like that, with their spines cracked and their pages splayed and crumpled. “I have to put them back.”

So Mama knelt beside me and we put all the books back on the shelves. Then we both got into her bed, which hadn’t been attacked like mine.

I was certain I wouldn’t be able to sleep, but the bed was so soft, and I was suddenly so overcome with exhaustion, that the next thing I knew I was waking up to the sound of birds singing outside the window. I had a few untroubled seconds before I remembered, and my stomach contracted so violently that I had to run to the bathroom.

The bathroom looked just as it always had. It was the one room the Nazis had left alone.

CHAPTER FOUR

What About Mitzi?

The next morning Frau Gumpert, my former best friend Ingrid’s mother, came to see us. When she saw the state of the apartment, she burst into tears.

“I’m so ashamed. I’m so ashamed to be German. I don’t know what’s happened to my country.”

Mama tried to comfort her. “It’s not your fault. And you shouldn’t be here. I don’t want to put your family in danger.”

But Frau Gumpert only went home to fetch some of her cups and plates, and bring us bread and coffee. Then she insisted on staying all day to clean up the apartment, so Mama could spend the time making phone calls to find out where Papa was.

Herr Pulver, from the apartment above ours, also came to see us. He apologised for not doing anything to help during the night.

“I’m a coward. I was too afraid of what they’d do to my family if I tried to stop them.”

“Of course,” said Mama. “It’s not your fault. You can’t put your family in danger.”

“How can I help?” he asked. “What do you need?”

“There’s no need,” said Mama. “You mustn’t take risks for us.”

But he was desperate to do something, so Mama asked him to repair the front door. Herr Pulver hurried off to fetch tools and wood. It soon became clear that he was no carpenter. After several hours of sawing and hammering, the mended door looked like very bad patchwork, but at least it had no holes in it. He fixed a padlock on the outside and bolts on the inside.

“Thank you very much,” said Mama. “It’s good to know we’ll be safe now.”

We all looked at the door. And I knew, with a certainty that came like a blow to the stomach, that the strongest door in the world would be no use at all any more.

After hours on the phone, Mama discovered that Papa had been taken to a concentration camp called Buchenwald. I had heard of concentration camps. They were prisons for people the Nazis didn’t like.

“He’ll be back soon,” Mama said. Her hands were shaking.

“When?” I asked.

“Soon.”

“But you don’t know that, do you? What if he doesn’t come back?”

Mama looked stricken, and I felt bad for saying it. But I was angry too. She shouldn’t say things if they weren’t true.

At five o’clock Frau Gumpert went home to cook supper for her family. She came back in the evening and told us there had been attacks on Jews all over Germany and Austria last night. Thirty thousand Jewish men had been taken to concentration camps. Almost every synagogue and thousands of Jewish homes and businesses were destroyed.

The Nazis said they had done this in revenge for a Jewish man shooting a Nazi official in Paris.

It became known as Kristallnacht. The Night of Broken Glass.

The next day Mama found out that Uncle Paul had also been taken to Buchenwald. It sounds awful, but at first I actually felt glad. At least he would be with Papa. At least they’d have each other.

Then I felt dreadful. Poor, poor Uncle Paul. Now he wouldn’t be able to go to Paris.

Suddenly a terrible picture flashed into my head.

“What about Mitzi? We have to go and find her.”

“We will,” said Mama. “Later.”

“Not later! Now! What if they hurt her? What if she’s trapped under something? We have to go now.”

Mama looked at me. “All right. We’ll fetch her now.”

Uncle Paul lived in a sunny, high-ceilinged apartment on the main street, next to Herr and Frau Heinkel’s drapery store. The Heinkels had had that store since Mama was a child. Mama always took me there to buy coats and shoes and dress material. I loved choosing the fabric for my summer dresses from the rolls of pretty cottons.

As we walked up the street, I gasped and grabbed Mama’s arm.

“Look!”

The windows of the Heinkels’ store were smashed to pieces. All that was left were a few jagged shards around the edges. Inside, the shelves had been pulled off the walls and the shop was completely bare except for torn scraps of paper and trampled ends of ribbons on the floor.

As we stared in horror, the door from the back storeroom opened and Frau Heinkel came out. She looked frail and old. She stared blankly for a moment before she recognised us and attempted a watery smile.

Mama stepped through the hole where the plate-glass window had been and hugged her.

“I’m so sorry, Vera. I’m so sorry. Where’s Manfred? Did they take him?”

Frau Heinkel nodded. “Did they take Walter?”

Mama nodded too. Then she looked at Frau Heinkel’s wrinkled hands, which were criss-crossed with little red cuts and scratches.

“Oh, Vera, what did they do to you?”

“After they’d destroyed the shop,” Frau Heinkel said, “they ordered me to clear up all the mess. There was so much broken glass.”

“Did they steal all your stock too?”

Frau Heinkel shook her head. In a small, tired voice, she said, “Our neighbours came and looted it all. The police stood by and watched them. All our customers. Half those people, Manfred’s been giving them credit for years. I suppose they thought they could just help themselves to the rest.”

Mama’s eyes were filled with tears. “I’m so sorry, Vera. It’s just terrible. Where are you going to go? You can’t stay here on your own. Do you want to come and stay with us?”

“That’s very kind, Edith, but I’m going to stay with my daughter in Frankfurt tomorrow. She’s trying to get us all visas to go to Palestine. Where are you going to go?”

Mama shook her head. “I don’t know. I don’t know anything any more.”

“You have to get out,” said Frau Heinkel. “You know that, don’t you? You must get out.”

Mama nodded slowly. “We didn’t want to leave. Walter was so sure things would get better. But now…”

She left the sentence unfinished, and she and Frau Heinkel said a tearful goodbye.

“We won’t leave before Papa gets back, will we?” I asked, as we stopped in front of Uncle Paul’s apartment block. “We’ll wait for Papa?”

“Of course,” said Mama.

Always before, as our friends and family had emigrated one by one, I’d been glad we were staying. I didn’t want to leave our lovely apartment, with my cosy bedroom and all my precious things. But now, all I felt was relief. It was obvious we couldn’t stay any more.

I wondered where we’d go. I hoped it would be England. I had seen the pictures of King George VI’s coronation in the magazines and newspapers. The king and queen and the little princesses had looked so splendid in their jewels and cloaks. It seemed like a different world.

Mama had brought her set of keys, but Uncle Paul’s apartment was unlocked. The front door wasn’t damaged though. Maybe he’d let the storm troopers in before they smashed the door down.

I was terrified of what we might find, but the apartment hadn’t been destroyed as badly as ours. Cupboards had been opened and ransacked, and all the papers pulled out of Paul’s desk, but the furniture was still intact.

To my joy and relief, Mitzi was curled up in her usual spot on the window seat. I gave her a big cuddle before I went to fetch her wicker basket from the kitchen.

As I crossed the hall, there was a sharp knock at the door. We froze. The contents of my stomach turned to water.

“Heil Hitler!” barked an unknown voice. The door opened and an SS officer stepped into the hall, in black uniform with gleaming buttons and boots. He frowned at Mama. My teeth started to chatter. I tried to clamp my mouth shut but I couldn’t control it.

“This is not your apartment, I believe,” he said.

Mama had turned very pale. “It belongs to my brother.”

“My commanding officer needs this apartment. He will be taking possession of it tomorrow morning. Give me the key.”

“But what about my brother’s things?”

“You will leave everything as it is. Take nothing with you. Give me the key. That is an order.”

Without a word, my mother handed the front door key to him. He turned it over in his palm, then tried it in the lock. Once he was sure it was the right key, he thrust out his arm again, said, “Heil Hitler!” and ordered us to leave.

“I have to get Mitzi,” I said.

My mother shot a terrified glance at the officer. He said nothing. I went into the living room and scooped Mitzi’s warm, furry body up from the window seat. Mitzi liked being cuddled and she snuggled happily into my arms.

“Aren’t you a beautiful cat?” the officer said, in a soppy voice, as I carried her through the hall to the kitchen.

He reached out and stroked her. Was he going to take Mitzi too? I tightened my hold on her. If Paul came back and found her gone, it would break his heart. I put her in the basket and fastened the straps around the lid. Mitzi hated going in the basket. She started to yowl.

“Shh, be quiet,” I whispered. “You won’t be in there for long.”

I remembered that Paul always put food in the basket to keep her quiet. Too late now. I had to get her out before the officer ordered me to leave her behind.

I held my breath as I carried her through the hall. But the man said nothing. He waited for Mama and me to leave the apartment, and then he locked the door behind us and pocketed the key.

CHAPTER FIVE

Jews Are Not Wanted

I was nervous and jumpy all the time now. What made it worse was that I could tell Mama was frightened too. She tried to pretend everything was fine, but she jumped whenever the phone rang or there was a knock at the door.

It was worse, too, because I couldn’t go to school any more. Jewish children were now banned from German schools, and the nearest Jewish school had been burned down on Kristallnacht. So I had to stay at home all day. We only went out to buy food and essentials. I insisted on going with Mama every time she left the apartment, even if she was just going to buy bread. I knew it wasn’t logical, but somehow I felt she would be safer if I was with her.

But Mama had a great idea.

“Let’s learn English,” she said. “We can surprise Papa by speaking perfect English to him when he gets back.”

“When he gets back” was a phrase we both used a lot at that time. I had trained myself not to think about what might be happening to Papa. It felt as though I had a little box inside my head, where I locked away all the things I didn’t allow myself to think about.

We had learned a little bit of English at school. But when Mama was a child, her parents had wanted her to learn the language, so she’d had an English nanny for a while, and she had kept all her English workbooks.

My new best friends were two little leather-bound pocket dictionaries: a red one, which was German to English, and a blue one for English to German. I became completely absorbed. When I was learning English I could forget about the horrible world outside, sometimes for hours at a time. I made Mama test me on my vocabulary and at mealtimes we would try to speak in English. She had forgotten a lot, but it came back to her quite quickly, and she could correct my pronunciation.

Learning English and having Mitzi to keep me company made my new life indoors more bearable. In any case, even if we had gone outdoors, there was barely anywhere we could go. Jews were banned from parks, swimming pools, theatres, cinemas and ice rinks. The notices were everywhere: Juden Sind Unerwünscht. Jews Are Not Wanted.

Then, three weeks later, I woke one morning and heard a man’s voice in the apartment. My stomach clenched. Rigid with terror, I listened.

It wasn’t shouting. It was a quiet voice. It sounded like…

No. It couldn’t be.

Could it?

A gentle knock at my door.

“Anna?” my mother called softly.

I sat up in bed, holding my breath.

The door opened. A figure stood in the shadowy doorway.

“Papa! Oh, Papa!”

I leapt into his arms and hugged him and hugged him. He hugged me back tightly and I laid my head on his chest, flooded with happiness.

But when we finally let each other go and I stepped back and saw him properly, I was shocked.

He looked stooped and thin and much, much older. He had bruises and cuts on his face, and he wasn’t wearing his glasses. His hair was greyer and thinner and his hands trembled.

“Oh, Anna, it’s so good to see you. You look so well. I’m sure you’ve grown.”

“Sit down, Walter,” said Mama gently, and we all sat on the bed, Mama and I on either side of Papa. He put an arm around each of us and we snuggled up together, my head on his shoulder.

“It’s so wonderful to be back with my girls. I’ve missed you so much.”

“You’re so skinny,” I said. “What did they do to you?”

He shook his head quickly, as though trying to dislodge the memories. “Let’s not talk about that. Tell me all about you.”

“But—”

He took my face in his wrinkled, shaking hands. They were like the hands of an old, old man.

“No more questions, Anna.”

“But—”

Mama gave me a warning look. “Anna, you mustn’t ask. Really. They told Papa that if he says anything about what happened there, they’ll come and get him again.”

I turned cold. What had they done to him? What must his life have been like in that camp?

“Anyway,” said Papa, “now that I’m back, I just want to hear about you. Tell me what you’ve been up to.”

He was clearly making a huge effort to seem normal. If he could be that brave, after a month in a concentration camp, then there was no excuse for me not to be brave too.

“We have Mitzi now,” I said. “We went to Uncle Paul’s flat and fetched her. I made her a toy from a cork tied to a piece of wool and she loves it. When I pull it around the apartment she chases it and pounces on it like it’s a mouse.”

“That’s good,” he said. “Paul will be pleased.”

“Did you—” I began, and then I stopped. I had been going to ask him whether he’d seen Uncle Paul in Buchenwald.

“Mama says you’re learning English,” Papa said. And, relieved to have found a safer topic, I told him about the irregular verbs I’d learned yesterday.

CHAPTER SIX

Anna Must Go

A few days later, Uncle Paul came out of Buchenwald too. Since the Nazis had taken his home, he came to live with us until he could get to France. His emigration papers had expired while he was in the concentration camp, so he had to go to the consulates every day to try to get the necessary permissions again.

Papa couldn’t go back to work. While he was in Buchenwald, the Nazis took his publishing company. They made a law that all Jewish businesses had to be transferred to non-Jewish owners.

Now it wasn’t only Uncle Paul telling him we had to get out of Germany. Everyone we knew told us to leave. And Papa, who looked older and sadder every day, finally agreed. He left the apartment each morning at the same time as before, but instead of going to his office he and Uncle Paul spent every day in queues at the foreign consulates, trying to get the right papers to go to America, Holland or England. But every week the Nazis were making new rules about emigration, and each new law meant new documents were needed. You had to have several