Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

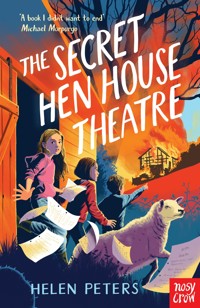

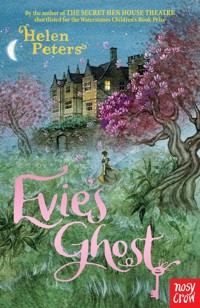

Compelling period fiction for 9+ readers from the Waterstones Children's Prize shortlisted Helen Peters. Evie couldn't be angrier with her mother. She's only gone and got married again and has flown off on honeymoon, sending Evie to stay with a godmother she's never even met in an old, creaky house in the middle of nowhere. It is all monumentally unfair. But on the first night, Evie sees a strange, ghostly figure at the window. Spooked, she flees from the room, feeling oddly disembodied as she does so. Out in the corridor, it's 1814 and Evie finds herself dressed as a housemaid. She's certain she's gone back in time for a reason. A terrible injustice needs to be fixed. But there's a housekeeper barking orders, a bad-tempered master to avoid, and the chamber pots won't empty themselves. It's going to take all Evie's cunning to fix things in the past so that nothing will break apart in the future... Absorbing, brilliant storytelling from the author of The Secret Hen House Theatre, The Farm Beneath the Water, Anna at War and The Jasmine Green Series for younger readers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 317

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Freddy

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

Victoria Station

“Can I have a large hot chocolate with cream and marshmallows, please?” I said to the man at the counter. “And one of those doughnuts too.”

I rummaged in my bag for my purse and took out one of the crumpled notes Mum had shoved at me in the back of the taxi.

“For emergencies,” she’d said.

Well.

At this very moment, my mother was on her way to Heathrow Airport with her shiny new husband, who was sweeping her off for a romantic honeymoon on the Grand Canal in Venice.

I, on the other hand, had been dumped outside Victoria Station on my own, with instructions to catch a train to the middle of nowhere, to stay with an ancient godmother I hadn’t seen since I was a baby.

And if that isn’t an emergency that requires a large hot chocolate and a doughnut with sprinkles, then I really don’t know what is.

CHAPTER TWO

The Outskirts of Nowhere

The train crawled towards Highfield at the pace of a dying slug. It was almost dark, and so far beyond the back of beyond that there was only one other person left in my carriage. He sat hunched over a bag of crisps, snatching them from the packet one by one and crunching them with quite unnecessary violence. I considered moving carriages, but then he might have thought I was scared of him. (Which I was, but I didn’t want him to know that.)

At this rate Mum would probably be in Venice before I got to Highfield Station. And then it was still another five miles by car to the house. With a godmother I knew nothing about, except she was seventy-two years old.

“You’ll like her,” said Mum. “She’s lovely.”

Which meant nothing. It’s what Mum says about everybody who isn’t an actual criminal. Anyway, all her attention at the time was on the half-packed suitcase open on her bed.

“This one or this one?” she asked, holding up two floaty summer dresses. I shrugged. It was freezing in London. But in Venice, of course, it would be perfect summer weather.

“Maybe both,” said Mum. “They weigh practically nothing anyway.”

It wasn’t meant to be like this. I was supposed to be staying with my best friend Nisha while Mum was away. But then Nisha’s grandfather died and they had to go to India, so Mum decided to pack me off to my godmother’s instead. I’d much rather have stayed in the flat by myself, but she wouldn’t hear of it.

“You’re only thirteen. I can’t leave you on your own for five days. Anything could happen.”

“What could happen, exactly? I’ve lived here my whole life and nothing’s ever happened yet. Anyway, I can have friends round.”

“That’s exactly what I’m worried about,” said Mum. And then, as I opened my mouth to argue, “Don’t even bother, Evie. I’m not letting you stay on your own for a week and that’s final.”

So. Here I was. Happy holidays, Evie.

Big fat raindrops started to splat against the windows. There was nothing outside the train but fields and trees, all bleak and bare in the fading light. We hadn’t passed a house for miles.

On the plastic table, the cracked screen of my phone lit up with a text. I grabbed it with pathetic eagerness, hoping it was from a friend. But it was my so-called godmother.

Sorry, have to attend meeting. Get taxi from station. I should be home by the time you arrive. Anna

Well, what a lovely welcome.

I texted Mum to inform her of this new development. Maybe she’d actually feel a twinge of guilt about abandoning her only daughter to a woman who clearly cared more about some stupid village meeting than she did about looking after me.

If Mum could drag her eyes away from her perfect new husband for long enough to check her phone, that was. Which was doubtful.

I pressed Send, but there was no signal. Unbelievable. We weren’t even in a tunnel. Was this what it was like in the countryside?

I suddenly had a terrible thought. What if there was no signal at Charlbury? If I had to spend five days cooped up in a random old lady’s flat with no way of communicating with the outside world, I would literally die.

The rain was lashing down now, making long diagonal streaks on the windows. I thought about getting my sketchbook out to draw it, but then the train started to slow down.

Highfield. This was it.

Nobody else got out. The station was deserted. But there was one cab parked on the kerb. I walked towards it and the driver opened his window. I gave him the address, trying to sound as though I gave instructions to taxi drivers all the time. He nodded but didn’t say a word, which was really creepy. I couldn’t believe my godmother was actually ordering me to get into a car with a complete stranger. But I couldn’t see a bus stop anywhere and there was still no signal on my phone. So I didn’t really have a choice.

Within about a minute we left the houses behind and there was nothing beyond the rain-streaked windows but darkness.

The driver stayed silent. All I could see was his thick neck and the back of his bald head.

What if he wasn’t taking me to Charlbury at all, but to some deserted place where he was planning to kill me and bury my body?

After what felt like hours, he turned on to a narrow winding lane. There were no other cars on the road. I felt sick with fear. I kept my fingers curled around the door handle in case I needed to make a quick getaway. He didn’t look very fit. Maybe I could outrun him. Otherwise I’d have no chance.

The car slowed down. I thought I was actually going to throw up. I said frantic prayers inside my head. I’m not religious, but there was no one else to turn to.

He turned off the lane on to a narrow, tree-lined driveway. In the light of the headlamps, I saw a huge old house at the end of the drive.

“Charlbury House,” he said, slowing to a halt in front of it.

I felt weak with relief. I paid the fare – half my emergency money gone already – and got out of the cab. The wind was so strong that I could hardly open the door. I still felt shaky with fear, even though there was nothing to be scared of any more.

The rain was pelting down. A gust of wind whipped my hair across my face. As the taxi drove away, I pushed the long dark strands out of my eyes and looked up at the house.

It was massive. A huge, ancient, spooky stone mansion. Enormous windows with carved stone frames, and a grand flight of steps leading to the biggest front door I’d ever seen.

How could Mum have forgotten to mention I’d be staying in a mansion?

I walked up the steps, bumping my case behind me. A light came on above the front door, illuminating slanting rods of rain. Raindrops bounced off the stone slabs. There was a big puddle right in front of the door, where the stone had worn down.

Screwed to the wall beside the door, looking completely wrong on the ancient stones, was an ugly modern row of bells and an intercom. I pressed the bell for Flat 9.

I waited for ages but there was no answer. I pressed the bell again, harder this time.

Nothing. Either the bell wasn’t working, or she was still not home from her meeting.

Honestly. You’d think she might have made a tiny bit of effort, instead of leaving her goddaughter standing in the rain while she sat in a nice warm room wittering on about the village scone-baking crisis or whatever it was that was so much more important than collecting me from the station.

Unless I’d pressed the wrong bell. I pulled my phone from my pocket to check the address.

But my hands were cold and wet, and the phone slipped through my fingers. I tried to grab it, but my fingers closed around thin air and my phone splatted right into the middle of the puddle.

“Oh, no, no, no!”

I fished it out of the water and wiped it frantically on my coat, but my coat was soaking too, and the phone was just getting wetter. I unzipped my coat and tried to rub it dry on my top.

A beam of light shone on the front door and I turned to see a sports car speeding up the drive. It veered sharply in front of the steps, throwing up gravel all around it, and braked next to the house.

Somebody got out of the car and crunched briskly across the gravel. The person bounded up the steps, and I saw it was a little old lady. But not a normal old lady. She wore orange baseball boots with black trousers and a red jacket, and a broad streak of her silver hair was dyed bright pink.

“Are you Evie?” Her voice was clipped and businesslike. “You look very like your mother. I hope you haven’t been waiting long. I thought I’d be home earlier, but these councillors do love the sound of their own voices. Never use one sentence when you can use ten, that seems to be their motto.”

I said nothing. I was staring at her hair.

“Do you like it?” she asked, pulling out the pink strand with her thumb and forefinger. “I was tempted to dye the whole lot, but it takes a lot of work to maintain it, apparently. I might still do it at some point though. It’s very cheering when one looks in the mirror, I find. Distracts from the wrinkles. Now, where’s my key?”

As she rummaged in her shoulder bag, I looked at her jewellery. Enormous earrings, a huge necklace and a vast number of heavy-looking rings on her slim fingers. Her nails were painted silver.

From the depths of her bag, she pulled out a key ring in the shape of a skull.

“Are you Anna?” I asked, trying to adjust the image I had formed in my head to this pink-streaked, orange-booted, silver-nailed reality.

“I am. I suppose I should have said. What’s wrong with your hand? Have you hurt it?”

“It’s not my hand,” I said, withdrawing it from inside my coat. “My phone fell in that puddle. I was trying to dry it.”

She frowned at the screen. “The water will have got in through the cracks. It’s probably dead. No great loss. The reception here’s terrible anyway.”

“It’ll be fine if I put it on a radiator,” I said, seething. How dare she tell me it wasn’t a loss?

She unlocked the front door and I followed her in. The inside of the house was much less fancy than the outside. Standing in this hall, you wouldn’t have known you were in a mansion at all. It looked just like the communal hall of our block of flats in London, only bigger. Same chipped magnolia paint, same pile of junk mail, same dog-eared notices on the wall.

Anna led the way up a staircase with an ugly brown carpet, threadbare in the middle. We climbed two flights of stairs to the second-floor landing.

“Here we are,” she said, stopping outside a white-painted door with a lopsided brass number nine screwed to it. It opened on to a corridor with several doors leading off it. Anna opened the nearest door.

“This is the living room,” she said. “Also the kitchen and dining room.”

Seriously? I thought. She expects me to live in this?

“It’s not very tidy, I’m afraid,” she said, not sounding the least bit bothered, “but I’ve never been interested in housework. Such a waste of time, don’t you think?”

OK, I admit I’ve said similar things to Mum many times, when she’s having one of her regular rants about me leaving stuff all over the flat and never clearing up after myself and blah blah blah.

But this place…

Well.

The sofa, the chairs, the table, most of the floor and all the kitchen surfaces were buried beneath piles and piles of papers and pens and folders and magazines and books. Empty mugs and crumb-strewn plates teetered on top of every pile.

I was suddenly struck by the thought that this was probably what our flat would look like if Mum didn’t clear up after me.

“I don’t cook much,” said Anna breezily, following my eyes to the hob heaped with books. “Things on toast mainly, and I tend to eat in bed. One of the perks of living alone. You won’t mind getting your own meals, will you? I don’t know what sort of food you like, but you can go to the shop tomorrow and choose for yourself. I expect you cook a lot, with your mother out at work.”

I never cook. Mum always cooks when she gets home. But I didn’t say this. I couldn’t decide whether to be offended that Anna was clearly not planning on making the slightest bit of effort to look after me, or excited at the idea of living on crisps and chocolate for a week.

I laid my poor phone on the radiator. And then I noticed something truly disgusting.

“That’s not … real, is it?”

“My skull?” said Anna, smiling at the hideous toothy monstrosity grinning at me from the middle of the dining table. “Yes, he’s perfectly real. I call him Yorick. A useful reminder, don’t you think, of our mortality. None of us will be here very long, and when we’re gone that will be all that’s left. I should have taken him to that council meeting tonight. It might have encouraged them to hurry things along a bit.”

“What was the meeting about?” I asked, trying to take my mind off the skull and thinking how interesting it was that Mum had conveniently forgotten to mention the fact that my godmother was completely barking mad.

“Well, the part I went along for,” said Anna, her whole face lighting up, “was actually very exciting. There are new houses being built on this lane, and when they were digging the foundations, the builders discovered an old paupers’ burial ground – a graveyard for people who couldn’t afford a private funeral or who weren’t buried in the churchyard for other reasons. There are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of skeletons. The oldest remains may go back to the twelfth century. I can’t wait to get started on the dig.”

I stared at her. “You’re going to dig up graves?”

“Well, not personally. The archaeologists do that. I just examine the skeletons.”

“You examine dead bodies? For fun?”

She laughed. “Not just for fun, though it is fun. I’m a forensic anthropologist.”

“A what?”

“Essentially, I examine human skeletons to find out things about the person: their age, sex, how they died and so on. It’s a fantastic source of information on how people lived and died hundreds of years ago.”

“But aren’t you… I mean… I thought you’d be … retired?”

“Why would I retire, when I love my work and I’m good at it? I’ll take you to see the dig, if you like. Actually, you’ll be able to see it from your bedroom window.”

Oh, good. That was something to look forward to. I gave her a look that I hoped expressed my feelings, but she didn’t seem to notice.

“I need to go and do some work in my room,” she said, “but make yourself some supper if you’re hungry.” She gestured vaguely at the kitchen cupboards as she left. “Help yourself to anything you want.”

I opened the cupboard above the hob. It contained a box of teabags and three mugs. The one next to it was empty except for a sticky jar of Marmite and several tins of sardines. I’d never eaten sardines in my life and I wasn’t about to start now.

In the final cupboard was half a loaf of stale bread. The only things in the fridge were a small carton of milk and a piece of smelly cheese. There wasn’t even any butter, and what’s the point of bread without butter?

I decided to take a photo of the empty fridge. I needed to record my pitiful new existence. It might be useful evidence when my mother and her husband were put on trial for child cruelty.

Then I remembered. I took my phone off the radiator and tried to switch it on. Nothing happened. It was completely dead.

I tried not to panic. It just needs a bit more time to dry out, I told myself.

The silence was getting me down. I looked around the room for the TV.

A rising sense of panic built up inside me, followed by numb horror.

No. It couldn’t be true.

But it was.

There was no TV.

How could a room so full of stuff have literally not one thing in it that a human being actually needed? It was like I’d gone back to medieval times. I had literally nothing in the world, and I was practically an orphan, abandoned by my utterly selfish mother and sent to a crazy old skull-loving woman with no phone, no TV, no computer and no food.

I took out my book, but I couldn’t concentrate on reading. I looked around the room and saw nothing but endless hours of boredom stretching ahead of me.

So this, I thought, was to be my life for the next four days. Sitting alone in total silence, eating stale bread and Marmite in the company of a human skull.

CHAPTER THREE

The Writing on the Window

I had just finished my bread and Marmite when Anna reappeared.

“I just realised, I haven’t shown you to your room, have I?”

No, I thought, you haven’t. You are literally the worst hostess in the history of the universe. But I didn’t say anything. She might have thrown me out of the flat, and then I’d have been homeless as well as phoneless.

I picked up my case and she led me down to the far end of the corridor, where she opened a door, flicked the light switch and gestured for me to go in.

Unbelievable.

This room was even worse than the rest of the flat. And I wouldn’t have thought that was actually possible.

It was dark and gloomy, even with the light on, and it smelled of damp. The walls were a nasty, faded shade of brown. The curtains were thin and fraying. A bare light bulb hung from the ceiling. There was a stained, moth-eaten rug on the scuffed-up floorboards. And the only piece of furniture was an ancient-looking iron bed, bare except for a lumpy mattress.

“I never use this room,” Anna said. “Nobody’s slept in here for years.”

Great. That made me feel a whole lot better.

She gestured to an unbelievably dull-looking old pamphlet lying on the mattress. “That’s a history of the house,” she said, “in case you’re interested.”

I just about managed to stifle a snort.

“I’ll find you some sheets,” she said, and disappeared.

I walked over to the window, which was the only nice thing in the room. It was wide and tall, with a carved stone frame, and the glass was divided into dozens of tiny panes. Outside it was pitch dark. I couldn’t see a thing. Which was a relief, since the room apparently overlooked a graveyard where the bodies were being dug up.

As I reached out to close the curtains, I noticed a cluster of scratches in one of the panes near the bottom of the window. Scratches that looked like writing.

I crouched down and peered at them more closely. It was writing. The letters were curly and old-fashioned.

Sophia Fane

Imprisoned here

27th April 1814

The hairs on my arms prickled. Imprisoned? In this room? Why would somebody have been imprisoned in here?

I stared at the writing for a while, trying and failing to make sense of it. Then I remembered the pamphlet Anna had left on the mattress. It was called A Brief History of Charlbury House. I picked it up and skimmed through the pages, looking for a mention of Sophia Fane, but I couldn’t find anything about her.

Anna came in, holding a pile of crumpled bedding.

“Do you know anything about that writing on the window?” I asked.

“Oh, yes,” she said, dumping the bedding on the mattress. “There’s quite an interesting story there.”

“What is it?”

“Well, Sophia was an only child, and her father, Sir Henry Fane, apparently arranged a marriage for her with a very wealthy friend of his. Sir Henry was in a lot of debt, you see, so he needed Sophia to marry a rich man to restore the family fortunes. But Sophia fell in love with one of the gardeners instead. And when her father told her she had to marry his friend, she refused. So he locked her up in her room until she repented.”

I felt myself turning cold. “In here?”

“Yes, apparently this was Sophia’s bedroom. Well, part of her bedroom, I imagine. The rooms were all altered, of course, when the place was turned into flats, but this must have been her bedroom window. The legend has it that when she was locked up, she scratched those words and the date when she was imprisoned into the glass with her diamond ring.”

“So did she repent?”

“Not as far as anyone knows. Anyway, she was already engaged to the gardener. Her father didn’t know that, of course, but he soon found out.”

“How?”

“Well, it turned out that when he locked her up, she was already pregnant.”

“Pregnant? So what happened to the baby?”

“Apparently the baby was taken away from her while she slept. It was a little boy, they say. Nobody knows what became of him.”

I imagined Sophia waking up one morning and discovering her baby was gone. I imagined her pleading to know where they had taken him, and being met with stone-faced silence. How awful must that have been?

“What happened to Sophia afterwards?”

“That’s the strangest thing of all,” said Anna. “Nobody knows.”

“What do you mean? Somebody must have known. Her father must have known.”

“There are all sorts of rumours, and there have been ever since it happened. Some people say she ran away and changed her name. Obviously there were no photographs in those days, so it was quite easy for a person to create a new identity without being traced. But other people think she was kept locked up for the rest of her life, and died of a broken heart. There’s even a rumour that she was murdered by her father.”

“Murdered? In this room?”

“It’s all just speculation,” Anna said, “because nobody has ever known the truth. But whatever happened to her, she was never seen again, and she was the last of the Fane family. After her father died, the house passed to a distant relative who kept it as a country retreat, but hardly ever used it. It wasn’t lived in properly again until it was turned into flats a few decades ago. Right, I’ll find you a towel. And is there anything else you need?”

Yes, there is, I thought. Several things, actually. A decent bedroom. My phone. My own home.

“No, thanks,” I said. “I’m fine.”

CHAPTER FOUR

The Girl in the White Nightdress

I turned over in bed and shook the pillow again. The pillow was hard and lumpy and the duvet was thin and lumpy. The mattress was chilly with damp. I was freezing cold.

The clock on the living-room mantelpiece had struck eleven a while ago, but I couldn’t sleep. Since Anna had told me the story of Sophia Fane, I couldn’t stop thinking about her, locked up in here, grieving for the baby who was stolen from her while she slept.

There was a hideous moaning, whistling sound coming from behind the wall opposite the bed. It had freaked me out so much earlier that I’d made Anna come and listen to it.

“It’s just the wind in the chimney,” she said. “There would have been a fireplace there, you see, before the house was turned into flats. The fireplace was blocked up but the chimney’s still there behind the plasterboard.”

It didn’t sound like wind in the chimney. It sounded like a pack of ghosts, howling in the walls. It was the most horrible sound I’d ever heard.

I turned over again and thumped the pillow. The ghosts in the chimney howled even louder.

As if this room wasn’t uncomfortable enough already, when I took out my things to get ready for bed, I realised I’d forgotten to pack any pyjamas. Anna insisted on lending me a nightdress. I didn’t know nightdresses still existed. I thought they’d died with the Victorians. It was made of white cotton and came down to my ankles, with buttons at the front and a high frilly collar. It felt really weird to wear, and it smelled weird too. A strange, old-fashioned smell.

A high metallic strike made me jump. But it was only the living-room clock. It struck twelve, and the last stroke faded away.

And as it faded away, the wind stopped whistling in the chimney. The water stopped gurgling in the pipes. The breeze stopped rustling in the trees.

I had never known such silence. It was as though the world was holding its breath.

I realised I was holding my breath too. I forced myself to breathe.

The howling in the chimney started again: a terrible, desolate, lonely, wailing sound. I covered my ears with my hands.

Tap, tap, tap.

I screamed. Something was rapping on the window.

I burrowed down into the bed and pulled the duvet over my head, whimpering with terror.

The wailing grew louder. Skeletal fingers knocked on the glass. Tap, tap, tap.

My teeth were chattering and I shivered uncontrollably. I thought I might die of fright. I wanted to run but I couldn’t move.

Tap, tap, tap.

I made myself breathe. It was just a tree branch, tapping against the window, I told myself. There must be a tree outside the window.

I couldn’t just lie there whimpering all night. I had to be brave. I had to go and see.

I forced myself to get out of bed and walk across the pitch-black room. I held my breath and pulled the curtains open.

A girl in a white nightdress was staring in at me. A girl with long dark hair and a desperate look in her eyes.

I shrieked and jumped back, my blood pumping, my heart racing.

Then I realised. It was my reflection. It was just the nightdress that had scared me. I wasn’t used to seeing myself in a nightdress.

I forced myself to look again. My reflection looked back at me.

Except … it didn’t look exactly like me. And it didn’t look like a reflection.

Don’t be stupid, I told myself. Of course it’s your reflection.

From somewhere outside the house came a whirring noise. And then another clock started to strike, with a deep, resonant sound that lingered in the air.

That was strange. I had heard the living-room clock strike every hour this evening, but I was sure I hadn’t heard that other clock before.

The clock continued to strike. And my reflection raised its hand.

What?

I hadn’t raised my hand. Had I?

Then the hand…

No. It couldn’t have done.

I was stone cold. Goose pimples prickled all over my body.

I must be going mad, I told myself. I must be hallucinating.

Because I was sure the hand had beckoned to me.

Had I just beckoned without knowing it? Was that possible?

Ice-cold with dread, I raised my arm.

The girl in the window didn’t raise hers. She just stared at me with a pleading look in her eyes. As I lowered my arm, flooded with terror, she reached hers towards me and beckoned again.

“Help me,” she mouthed.

I screamed, yanked the curtains back together and ran from the room. There was no way I was going back in there. No way I was staying in this flat. I would wake Anna and make her take me back to London, back to my own home, right now, this minute.

As I ran through the doorway, I had the weirdest sensation. For a moment, I felt as though I ceased to exist. It was as though my body had dissolved into thin air.

Then, as the door slammed shut behind me, the sensation faded and I felt solid and whole again. It must have been some sort of fainting fit, I thought, only without the toppling-over part.

But something was different. My clothes felt different. I looked down.

What the…?

Instead of Anna’s nightdress, I was wearing a long brown apron over a long grey dress and black boots. There was a tightness around my ribcage, as though I had some sort of corset underneath the dress.

What on earth was going on? Was it a dream? But I hadn’t fallen asleep. Had I?

I needed to wake Anna. I had my hand on her bedroom-door handle when suddenly I stopped and stared.

All the doors in her flat were modern and white, with cheap-looking handles in a dull-coloured metal.

But this was a door of polished wood, elaborately carved and panelled, and instead of a cheap chrome handle, my hand was clutched around a sphere of shining brass.

Still clutching the doorknob, I looked up and down the corridor.

Everything was different.

The doors were all of carved and polished wood, with gleaming brass doorknobs. The walls were no longer a dirty cream colour, but a lovely deep blue. Instead of the nasty brown carpet, I was standing on a beautiful patterned rug that ran right along the middle of the corridor. Around the edges of the rug, polished floorboards gleamed in the light of flickering wall lamps.

I was trying to take this in when Anna’s bedroom door was flung violently open, knocking me into the opposite wall. A thin, tight-faced, middle-aged woman wearing a long grey dress marched out of the room. Her eye lit on me and she frowned.

“Are you the new housemaid?” she asked in a strong French accent. “What are you doing up here? Did Mrs Hardwick send you?”

I stared at her, speechless. She tutted. “Another brainless idiot,” she said, shaking her head. “Where does she find such hopeless girls? Get back to the kitchen. Polly is on fires tonight.”

I didn’t move. I couldn’t move. The woman gave me a shove in the small of my back, propelling me down the corridor.

“Get along with you, girl. This is no time to stand around dreaming.”

Head spinning, I walked away from her down the corridor.

I pinched my arm as hard as I could.

It hurt.

But I already knew it would. Because this didn’t feel one bit like any dream I’d ever had. Was I having some kind of crazy hallucination? Or had I gone completely mad?

CHAPTER FIVE

Polly

I opened the door that should have led out of Anna’s flat to the landing. It did lead to the landing, but the landing was different. The walls were white now and the brown carpet had gone, leaving bare wooden boards.

In a fog of confusion I gripped the banister rail and started to walk downstairs. The boots rubbed my toes, and whatever was on my legs itched like mad. I hitched up my dress and saw that I was wearing long thick woollen socks. And my hair was different too. I put my hands to my head. My hair was pinned into a tight bun.

I couldn’t even begin to make sense of this. My brain was unable to form a single coherent thought.

Delicious food smells wafted up the stairs and there was a distant clatter of pots and pans. As I got further down, I could make out muffled voices among the other noises.

At the bottom of the staircase was a stone-floored passageway with three doors leading off it. I was trying to decide which one to go through when the door behind me swung open and a huge hand grabbed my arm.

I shrieked, whirled round and found myself facing a man dressed like one of the footmen on Cinderella’s coach. He stank of body odour.

“Let go of me!” I said, trying to shake off his hand.

He tightened his grip. “What on earth do you think you’re playing at?” he said, almost knocking me out with his terrible-smelling breath. “They’ve been wanting you in the scullery for hours.”

At least, I think that was what he said. His accent was so strong that it was hard to make out his words. Also, I was distracted by his hair, which was long and grey, and curled like a judge’s wig. And yet his face didn’t look older than a teenager’s.

“Nell’s been taken sick,” he said. “Cook needs you to do the pots and pans. Have you finished the bedrooms?”

I gaped at him dumbly. “Er…”

“Are you half-witted?” he said. “Stop gawping and get yourself to the scullery if you still want a job in the morning.”

“Er … where’s the scullery?”

He shook his head, as though he couldn’t believe what he was hearing.

“Follow me.”

He led the way down the passage and I took in his extraordinary clothes. He wore a dark-blue velvet tailcoat trimmed with gold braid, velvet knee-length knickerbockers, stockings and gold-buckled shoes. It really was like he’d just stepped out of a fairytale.

He opened the door at the end of the passage and led me into an enormous old-fashioned kitchen. It was boiling hot. A big open fire burned in the centre of a massive black oven. A great long wooden table ran down the middle of the room. At the far end of it, a fat woman sat in a high-backed armchair facing the fire.

“Take those knives to the pantry, Alice,” she snapped to a skinny, exhausted-looking girl in a filthy apron. “And all the dirty pots to the scullery.”

“Yes, missus,” muttered the girl, collecting up an assortment of lethal-looking knives from the huge table. The woman heaved herself up from the chair with a groan. As the girl passed her, the woman, for no reason that I could see, hit her on the side of the head. The girl whimpered and disappeared through a doorway, past another girl scraping food scraps into a metal bucket.

“And don’t you even think about going to bed before this place is cleaned until it shines,” called the fat woman, hobbling out of the kitchen. “I’m off to my room. My legs are fair murdering me.”

“Not surprising, with all that weight on them,” muttered the girl scraping plates, as soon as the woman was out of earshot. I laughed and she looked up. She had a lively, expressive face and I liked her straightaway. She looked about my age, and she was dressed exactly the same as I was.

Her eyes widened with surprise when she saw me. Then she turned to the curly-wigged man, raised her eyebrows and gave him a sly grin.

“Ooh-er, George, this your new fancy piece?” She had the same strong accent as he did.

“Give over, Polly Harper,” he said. “You mind your cheek.”

Polly winked at me.

“You’ll be the new girl then,” she said. “You took your time.”

The girl in the dirty apron came back through the door. “This is Alice,” said Polly. “She’s the kitchen maid.”

Alice shot me a look of such hatred that I turned around to see who was behind me. But there was no one. That look really had been directed at me. What had I done?

Polly didn’t seem to have noticed. “And this is the new housemaid,” she said to Alice. She turned to me. “What’s your name then?”

“Evie.”

“That’s a pretty name.”

Alice scowled.

“Foreigner, she be,” said George. “Addle-pated too, I shouldn’t wonder. Probably dropped on her head as a baby. I’ll leave her to you, Polly. I’ve got better things to do than stand around making introductions.”

He left the room and Polly nodded her head in the direction of the door in the corner. “Scullery’s the first door on your left,” she said. “Best get started on those pots and pans if you want to get to bed before midnight. I’m off to check the bedroom fires. I’ll come and see how you’re getting on in a bit.”

According to the big clock on the wall, it was nearly eleven. But for me, it was well after midnight and I suddenly felt exhausted. I had no idea what was going on but I wished it would stop. I pinched myself again, as hard as I could bear. It hurt, but nothing happened.

The scullery was a small room, lit only by one weak lamp. The wooden draining board that ran all along the far wall was piled high with dirty pans and utensils. If they were expecting me to wash up that lot at eleven o’clock at night, they had another think coming.

“So you’ve arrived at last,” said a harsh voice.

I wheeled around to see a broad-shouldered, very upright woman standing in the doorway. Her grey hair was scraped back in a tight bun and a huge bunch of keys hung from a chain at the waist of her plain black dress.

“Well, have you nothing to say for yourself?”

I stared at her. What did she expect me to say?