Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Serie: Helen Peters series

- Sprache: Englisch

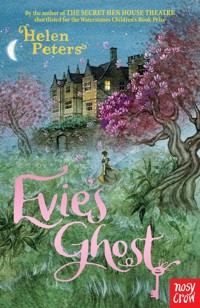

Since the death of her mother, Hannah's family life has been somewhat chaotic. Her father is absorbed by running their dilapidated farm, and the four children are increasingly left to their own devices. These include "farming" each room of the house, looking after an enormous pet sheep called Jasper, and writing and directing plays in a disused hen house. But when the farm is threatened with demolition, Hannah determines to save it and realise her dreams at the same time... Shortlisted for the Waterstones Prize, this is a brilliant story of eccentric family life where the children's imaginations run as free as the farmyard animals. From the award-winning author of Evie's Ghost, Anna at War, The Farm Beneath the Water and the Jasmine Green series for younger readers, this is perfect for fans of Iva Ibbotson and Philippa Pearce.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 330

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

v

To my parents and in memory of my grandparents

vi

vii

viii

Chapter One

The Stranger

BANG, BANG, BANG!

Somebody was trying to smash the scullery door down.

Hannah sat cross-legged on her bedroom floor, hunched over a piece of paper, her pen racing across the page. Even inside the farmhouse her breath came out in white trails, and the cold sneaked its way right through her woolly hat and three jumpers.

BANG, BANG, BANG!

Her right hand didn’t leave the page as she glanced at her watch. Five to two. But it couldn’t be Lottie. She never knocked. She just walked right in and yelled up the stairs.

One of the others could get it for once. She had to finish this by two o’clock.

BANG, BANG, BANG!

“Will someone answer that blasted door!” shouted her dad from the farm office.

There! Finished at last. Hannah wrote “THE END” in large capital letters. This play would win the competition, she just knew it. 2

BANG, BANG, BANG!

“Hannah!” called Dad.

“Oh, OK.” Hannah slid her mother’s copy of Putting On a Play under her bed and scrambled to her feet. She must remember to put that back in Mum’s bookcase later.

“If it’s for me, tell them I’m not in,” Dad called as she passed his office door. “And get the others ready. There’s a pig wants bringing up from the Anthill Field.”

Hannah ran down the splintered back stairs, script in hand, ducking the cobwebs that hung from the crumbling ceiling. Her little brother Sam was already at the door, fumbling with the latch.

“It’s stuck again,” he said.

“I’ll get it, Sammy,” said Hannah. Sam moved aside. His laces were undone and his shoes were on the wrong feet.

BANG, BANG, BANG!

As Hannah wrestled with the battered latch, her eight-year-old sister Jo came through from the kitchen, a flat cap pulled down over her curls. A ginger guinea pig nestled into her left arm, nibbling a cabbage leaf.

“Who’s come?” she asked.

The latch shot up. Sam glued himself to Hannah’s side as she opened the door. Jo hovered by the stairs.

Looming in the doorway, stamping his feet against the cold, was a stocky man with a red face and a puffed-out chest. He looked like an irate turkey. His shiny dark hair was greased down on his head and 3he grasped a clipboard with his thick red fingers.

He stared at the children. “Flipping heck,” he muttered. His breath hung in the air.

What’s wrong with him? thought Hannah. She looked round but there was nothing, only the three of them in their holey jumpers and torn jeans. Had he never seen farm clothes before?

Click, clack, click, clack.

They all turned. At the top of the steep staircase, in a white minidress and red stilettos several sizes too big for her, stood ten-year-old Martha, one hand on her hip and her chin in the air.

“Martha,” said Hannah, “you’ll die of pneumonia. Go and get changed. And take Mum’s shoes off. Dad’ll go ballistic.”

“Oh, shut up,” said Martha. “You’re just jealous cos I look like a model.”

The man raised his eyebrows. Martha tottered down the stairs and pushed past Jo to get a good look at him.

“I’m looking for –” The man glanced at the clipboard. “Clayhill Farm.”

They said nothing.

“Is this Clayhill Farm?” he asked, louder now. “There’s no sign.”

“The sign blew down,” said Sam.

Hannah noticed a very new, very big, very shiny black BMW parked in the farmyard. At least, the top half was shiny. The bottom half was plastered in mud, like every vehicle that came up the farm track. 4

“In the records, it says it’s a working farm,” he said.

“It is,” said Hannah. Was he really thick or something? And who was he anyway, coming up here on a Sunday afternoon asking nosy questions?

“Really? Then what’s all this junk lying around for?” He flicked his hand around the yard. At the horse ploughs half buried in grass, the collapsed combine harvester rusting in the mud by the pigsties, the old doors, oil stoves and tangled barbed wire heaped up outside the house. “I mean, what’s with that old rust bucket?” He pointed towards the tractor shed where Dad’s vintage tractor stood. “What is it – an engine from the Age of Steam?”

“It’s Daddy’s Field Marshall,” said Sam proudly. “It’s really old.”

“Huh. You don’t say.”

Sam turned puzzled eyes to Hannah, and Hannah felt her cheeks flushing. How dare he be rude to Sam? And how ignorant was he? Didn’t he know Field Marshalls were collectors’ items?

“Can we help you?” she asked.

“I hope so.” He consulted his clipboard again. “I’m looking for Arthur Roberts.”

“Who shall I say is calling?”

“Just get him for me, will you?”

They all spoke at the same time.

“He’s out,” said Hannah.

“He’s milking,” said Jo.

“He’s in the office,” said Sam.

“I see,” said the stranger. “Busy man.” 5

They nodded.

“Well, is your mum in then?”

They were silent. Hannah had already seen quite enough of this stranger and she didn’t want him to know any more about their lives than he did already. What else was written on that clipboard?

Along the lane a bell sounded. Hannah looked up. Lottie Perfect was bumping up the track on her brand-new bicycle, weaving around the puddles and potholes.

“Can I take a message?” Hannah asked. She had to get rid of him. She needed every second of her time with Lottie.

“Give your dad this,” he said. “Make sure he gets it.”

Hannah took the envelope. Printed across the top were the words “Strickland and Wormwood, Land Agents”. And then, in red capital letters, “URGENT”.

Thank goodness she hadn’t called Dad. This man must be the agent for the new landlord. Hannah pulled on her coat and stuffed the letter and her script into one of the pockets.

The agent strutted off. Lottie, waving at Hannah from her bike, almost ran into him. She swerved wildly through a puddle. The children stared open-mouthed as a great brown wave of muddy water splattered all over the man’s trousers. Sam giggled, and that made his sisters laugh too. The agent glared at them as he opened his car door, and they laughed even more. 6

Lottie braked at the garden gate. She jumped off her bike and yanked the gate open. “Look at the state of me,” she said. “Have you got something to wipe this mud off, Han?”

“Right, you lazy lot!” shouted Dad down the stairs. “Look sharp!”

Oh, no, thought Hannah. If she got caught up in Dad’s pig chase, she’d be gone all afternoon and they’d never get the play done.

She threw Lottie a threadbare towel from the draining board, then grabbed Jo’s arm and pulled her outside, around the corner of the house. The guinea pig scrabbled across Jo’s jumper.

“Hey, careful with Carrots!”

“Jo, you have to cover for me. Please. I’ve got to read through the play with Lottie. We need to make sure it’s right so she can type it up. The competition closes on Tuesday – we have to send it off tomorrow.”

“Oooh, I’ve got to read my play with Perfect Lottie,” said Martha in a high-pitched singsong voice. “As if you’d win a prize with your stupid play.”

Hannah swung round. “Martha, get lost. It’s none of your business.”

“Like I care anyway,” said Martha. She stuck out her tongue at Hannah and teetered back inside.

Hannah turned to Jo. “Just tell him you don’t know where I am. Please, Jo. I’ve got to do this play – if we win, it actually goes on the radio and it might be my chance to be an actress!”

Dad’s heavy tread sounded from the stairs. 7

“I won’t tell,” said Jo. She placed Carrots in his hutch, sat on the scullery step and tugged on her muddy wellingtons. “Come on, Sam. Let’s get your boots on.”

Hannah skulked around the corner. Dad strode out into the yard with Sam trotting beside him. Jo followed them. And, finally, Martha emerged.

“Martha, please don’t tell him! I’ll give you anything!”

Martha shot her a contemptuous glance. “Like you’ve got anything I’d want.”

She kicked off the red stilettos and rammed her feet into an old pair of Jo’s boots. They were so much too small for her that she had to walk on tiptoe in them.

She staggered into the farmyard. “Dad, wait up!”

Dad was a good ten metres ahead of her and walking twice as fast. Hannah was spared. But not for long.

Chapter Two

The Pig

Once the others were a safe distance away, Hannah pulled Lottie into the yard. She could see her dad’s back as he strode across North Meadow with the others behind him, Martha swaying precariously in her squashed-down wellies.

“OK,” said Hannah. “Tractor-shed loft.”

Halfway across the yard, she looked back. Lottie was still at the garden gate. She looked as panic-stricken as a person stranded on a sandbank with the tide coming in all around them.

“Come on, they’ve gone now,” said Hannah.

“Can’t we just go in the house?”

“Don’t be stupid. That’s the first place he’ll look for me. Come on.”

“I can’t. I’ve got my new trainers on. I promised I’d keep them clean. If they get ruined my mum will kill me.”

Hannah let out an exasperated sigh. They were wasting precious minutes. She could go and get her trainers for Lottie but they had holes in the bottom and they’d be miles too small. Lottie was tall for 9eleven, and Hannah was little.

Little but strong.

She squelched back through the mud. “All right, hop up.”

“What?”

“I’ll give you a piggyback.”

Lottie giggled. “You’re mad. You’ll break your back.”

“I’ve carried heavier things than you. Get up, quick. They’ll be here with the pig in a minute.”

Hannah staggered across the yard, her thick straw-coloured hair falling into her eyes. Lottie clung on to her neck, half laughing, half screaming.

“Lottie, you’re strangling me!”

“Aargh, you’re going to drop me!”

“Stop squealing; you sound like a stuck piglet. Right, get off.”

She dumped Lottie on the floor of the tractor shed and sank down into the dirt, rubbing her shoulders and pushing the hair out of her face. Lottie’s smooth dark bob was as sleek as ever. She always looked as though she’d just stepped out of the hairdresser’s.

Lottie brushed the dust off her new coat. “Oh, guess what? You know the Linford Arts Festival’s coming up? They’ve got a youth drama competition – I saw a poster round the shops. We could do our play there.”

Hannah dragged the rickety ladder out from behind the Field Marshall. “We can’t,” she said as she propped it up against the trapdoor.

“Why not? You’re a brilliant actress. And then we 10could win, and that would serve Miranda Hathaway right for going on and on about how her drama group has won it for the last fifty million years.”

“But we can’t enter,” said Hannah as she stepped on the ladder. “It’s for proper youth drama groups. You have to have an actual theatre. Don’t you remember Miranda saying how the judges come out to your theatre and watch your play?”

“Oh. I forgot. Shame. It looked really good.” Lottie climbed up into the loft. “So have you finished the radio play?”

“I’ll show you.”

The loft was dark except for the far corner, where a narrow slit let in a shaft of grey February light. They groped their way across, ducking the beams and the cobwebs. Nobody ever came up here.

They clambered over mounds of rusty tractor parts and empty calf-medicine bottles to a pile of old feed sacks next to the window slit. Hannah’s muscles tensed at the thought of what might be lurking under those sacks. She bit her bottom lip, screwed her eyes shut and stamped her foot down on them. She held her breath, listening for the horrible sound of scuttling rodents.

Nothing.

Phew.

She plonked herself down on the sacks.

Lottie settled herself beside Hannah. “So?”

“OK.” Hannah reached into her pocket, pulled out the folded sheets of paper and flattened them on her lap. “Ta da!” 11

On the first page was written, in large flourishing letters: “By Her Majesty’s Appointment. A play for radio by Hannah Roberts and Lottie Perfect.”

“You didn’t have to put my name on it,” said Lottie. “I didn’t do anything.”

Hannah had struggled with this herself, but eventually her more generous side had won. “Well, you had some really good ideas. And you are going to do all the typing up. And then we can send it off tomorrow.”

Lottie clapped her hands in excitement. “Come on, let’s read it now.”

“We’re going to win, I know we are,” said Hannah. “Mum loved Radio 4. It’s a sign.”

Lottie reached for the script but her arm froze in mid-stretch as a cacophony of squeals and grunts blasted their ears.

“What’s that?”

The squealing got louder and more piercing as it was joined by the sound of running boots and thunderous swearing.

They looked down through the narrow slit.

Hannah’s father, holding a muddy board in front of him, was herding an enormous pink pig into the farmyard. As they watched, it shifted its huge weight on its tiny trotters, flicked around so quickly that no one could stop it and bolted back up the track.

Martha shrieked and jumped out of the way.

“Martha, you useless tool!” shouted Dad. “Joanne, get round behind her. Move!”

Jo ducked under the electric fence and raced 12through the field, trying to outrun the speeding sow.

“Sam, stand on the path there. Don’t let her past you, whatever you do. Martha, get down there and open the pigsty door. Move it!”

“Hadn’t you better go?” asked Lottie. “He’ll go mad at you later.”

“He’d go mad anyway. I’d only knock something over or get trampled by the pig. He’s moodier than ever at the moment.”

“Here she comes!” yelled Dad. “Sam, hold that board out! Martha, get her in the sty. Where the blazes is Hannah?”

“She’s in the tractor-shed loft with Lottie,” called Martha. “They’ve been there all the time.”

Hannah’s heart stopped. She stuffed the script back into her pocket. “Hide!” she hissed to Lottie. “Quick!”

But there was no time. She heard him shout, “Hold that!” and in three bounds he was up the ladder and in the loft. He glared through the gloom at the girls trying to disappear into the pile of empty sacks.

“What the heck do you think you’re playing at?” he shouted at Hannah. “Get down in that yard this instant!”

“Should I—” Lottie started to say.

“No, no, you stay here,” Hannah muttered. Clumsy with embarrassment, she heaved herself off the sacks and followed her father down the splintered ladder. The sow was racing up the track again, and Jo was trying to turn her round, leaping from side to side like a goalkeeper defending a penalty. 13

“Get over there!” Dad barked at Hannah, pointing at the entrance to the horse paddock. “Keep your wits about you and don’t let her past.”

Head down, Hannah trudged across the yard. A thin layer of mud, patterned all over with the spiky footprints of chickens, coated the concrete. Tractor tyres had churned the gateway into a mass of brown puddles. It was impossible to tell how deep they were until you stepped in them and the water slopped over the tops of your wellies.

Half a gate hung jaggedly off the one remaining hinge. If Dad ever got anything mended, Hannah thought, he wouldn’t have to use his children as fences.

Standing up to her shins in a pool of water, Hannah let her imagination take over.

“It is a great pleasure,” the radio interviewer would say, “to have with us the youngest ever winner of our playwriting competition, who also, of course, starred in the wonderful performance of her play which you have just heard. Hannah Roberts, you clearly have a great future ahead of you. What inspired you to write a play?”

“Well,” Hannah would say, “my mum loved acting, so maybe I get it from her. And in Year Six I was in the school play…”

How could she describe the joy of it? The fun of rehearsals. The excitement as the play starts to come together. The magic of creating a world from wood and words and fabric and sound effects. The buzz backstage, the butterflies in your stomach, the dazzle 14of the lights—

“Hannah, look sharp!”

Hannah looked up.

The sow was charging straight towards her. Its muddy snout and huge yellow teeth loomed closer. And closer.

She knew exactly what to do, and if she had been Dad, or Jo, or even Sam, she would have done it: leapt right into its path and stood her ground, confident that it would sense her dominance and change direction at the last moment.

If she had been Martha, she would have jumped out of the way.

Hannah did neither. She turned and ran. Lurched across the sodden ground, the pig sploshing and squealing behind her. Thick wet clay, heavy as concrete, clung to her boots.

Dad crashed through the hedge just ahead and ran full tilt towards the enormous sow at her heels.

And Hannah tripped over his boot and fell flat on her face into a gigantic puddle.

She staggered to her feet, soaked to the skin. Freezing water cascaded down her back and legs. The world had gone dark. Her eyes were stuck together with mud. She tried to wipe them but her hands and sleeves were coated with mud too. She could feel her hair plastered to her face. Through the muddy water in her ears she heard Martha’s laughter.

“Hannah, are you OK?” It was Jo’s voice.

“Yeah, great, thanks, how are you?” Hannah tried to say, but the mud got into her mouth and she had 15to stop to spit it out.

Jo wiped at Hannah’s cheeks with what felt like her coat sleeve.

“Eyes!” spluttered Hannah. “Wipe my eyes.”

Jo wiped her eyes. Hannah blinked them open. And let out a cry of horror.

“No, no, no!”

Scattered all around her, floating in the puddles, trampled into the mud, lay the pages of her script.

“Oh, no, no, no!”

Hannah scrabbled wildly about, picking up all she could see. Some pages had already been ripped by the pig’s hooves. Others tore as she tried to peel them off the ground.

Jo bent down to help but there was clearly no point. Barely a single word was legible.

“Have you got a copy?” she asked.

“It’s all handwritten – of course I haven’t got a copy.”

“Ha ha, you’ve lost your play,” said Martha. “Serves you right for trying to hide.”

Her dad strode over. Somehow he had managed to get the pig into her sty.

“Good grief, you look a state. Get up out of that puddle, for goodness’ sake. What’s all this fuss for, girl?”

Hannah said nothing. She stared down at the soggy brown scraps of disintegrating paper.

“It’s her play,” said Jo. “It fell in the mud and Gertie trampled on it.”

Dad looked at Hannah as though she’d just landed 16from another planet.

“Your what?”

“My play,” said Hannah. “I wrote a play.”

“Oh, for goodness’ sake. This is a farm, not a theatre. Get out of that mud, girl.”

He shook his head. Then his eye lit on an envelope floating in the puddle. The words “Strickland and Wormwood, Land Agents” and “URGENT” were just visible at the top.

“What’s this?”

“Oh,” said Hannah. “A man brought it. From the new landlord.”

“Ha! Good. Best place for it.” Her father tramped to the pigsty, and the letter sank deep into the mud under the weight of his boot.

He leaned over the wall and scratched Gertie behind her ears. “There you are, old girl. All safe and sound again. You just make yourself comfortable and I’ll fetch you some meal. I expect you’re thirsty too, eh, after all that running about? Let’s get you some more water.” He picked up a battered bucket and clumped across the yard towards the water tank.

Hannah stood completely still in the middle of the puddle, muddy water dripping from her hair, sodden clothes clinging to her skin. Lottie was standing open-mouthed at the bottom of the loft ladder. Hannah looked at Lottie, and at the loft, and she heard her dad’s words again.

“This is a farm, not a theatre.”

Her eyes were shining. She squelched across the yard as fast as she could under the weight of the mud 17and water. Her heart thumped with excitement.

Lottie’s look of pity and concern changed to one of bewilderment as she saw Hannah’s expression.

“Oh, my lord, Hannah, look at the state of you. What on earth are you smiling at?”

“Lottie,” said Hannah, grabbing her arm, “I’ve just had the most amazing idea.”

Chapter Three

The Poetry Competition

Miss Francis, Head of English, smiled around at the sea of navy blue and grey assembled in the school hall.

“Welcome, everyone, to our very first Key Stage Three Poetry Competition. We are most honoured to have with us as our judge a celebrity guest, local actress Monica Rowse, whom you will no doubt recognise from her numerous TV appearances. Thank you so much for coming, Monica.”

Monica Rowse crossed her slim legs and smiled graciously. Hannah, sitting next to Lottie in the middle row, scrutinised the actress’s face for clues as to her taste in poetry.

Hmm. Chicks and bunnies.

On the little table in front of the judge stood a small shiny silver cup. Hannah imagined the look of amazement on Dad’s face if she pulled that cup out of her school bag at teatime and showed it to him. Maybe then he wouldn’t think her writing was just a waste of time.

Her knuckles were white as she clutched her 19English exercise book. She had spent hours on her poem – poring over her thesaurus, writing and rewriting lines, trying out different rhythms and phrases, until it felt just right.

“This year’s theme was The Natural World,” said Miss Francis.

Danny Carr, sitting behind Lottie, yawned loudly. Hannah noticed that there was an empty seat next to him. Was he saving it for…?

Hannah’s heart thumped. How could she possibly concentrate if he came and sat right behind her?

Miss Francis consulted her list. “The first person to recite will be Miranda Hathaway, from 7B. Come up to the front, Miranda.”

Miranda didn’t have far to go. She was already sitting in the front row.

She made a great performance of taking her English exercise book from an expensive-looking bag printed with the words Hathaway Fine Art, Bond Street. Miranda liked everyone to know that her father owned a London gallery.

She opened her book and announced, “‘My Golden Retriever’.”

Miranda’s parents had probably hired a tutor and a poet to help her, Hannah thought. And they would have already entered her poem for the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Miranda flicked back her long shiny auburn hair and began to recite.

“His eyes of topaz jewels

His coat of shimmering hues…” 20

Hannah had seen that golden retriever. It was massively fat, with a permanent stream of dribble trailing from its mouth.

Lottie made gagging motions. “Did you think any more about the you-know-what?” she whispered.

“Of course I did,” said Hannah.

She had thought of little else since the idea had exploded like fireworks in her head as she stood in that puddle yesterday afternoon.

We could have a theatre in the tractor-shed loft!

She had been dying to talk about it since she got to school but it had been far too dangerous. Miranda and her best friend, Emily, sat right in front of them at registration and they must never, ever get wind of this.

Miranda continued to read her poem as if she were performing for the Queen.

“His ears of silken threads

His paws with velvet treads…”

Lottie nudged Hannah. “Look at this.”

She took from her bag a shiny red notebook. On the first page she had written The Tractor-shed Theatre Club. She flicked the page over.

“This is how I thought we could set it up,” she whispered.

Across the double page, Lottie had sketched a floor plan. Dressing room, wings, stage, auditorium.

Hannah stared at the sketch and her heart beat faster. The pictures leapt into her imagination: swishing curtains, lavish costumes, sumptuous scenery. She heard the wild applause from the 21audience as the actors took their curtain calls.

Lottie glanced up. The judge was gazing adoringly at Miranda as she wittered on about her big fat dog. “I’ve done costume designs too,” she whispered. She started to turn the page.

Applause broke out at the front of the hall. Miss Francis stood up.

“Thank you, Miranda. That was a beautiful tribute to your pet. Your use of metaphor was lovely. It is a shame,” she said, looking pointedly at Lottie, “that some people were not paying full attention. Perhaps you would do us the courtesy of listening properly from now on, Charlotte.”

Lottie dropped the red notebook into her bag and folded her hands in her lap, the picture of studiousness.

“Now, our next entrant is Emily Sanders from 7B.”

Emily rose from her seat next to Miranda and stood facing the audience. Miss Francis smiled and nodded for her to begin.

“‘My Horse, Starlight’,” announced Emily.

“Starlight is my best friend.

My love for him will never end.

I visit him every single day

To groom him, ride him and give him hay…”

Hannah gripped her exercise book and tried to concentrate on the poems. For the next twenty minutes her heart thumped against her ribcage as an endless succession of students praised dogs and cats, bluebell woods and willow trees, autumn leaves and 22summer sun.

Had she made a massive mistake? What on earth was the judge going to think of her poem?

But the natural world wasn’t all sunny and fluffy, was it?

Some people lived right in the middle of the mud.

Vishali Patel, from 8M, finished her poem about snow and returned to her seat. Miss Francis looked at her list and said, “And finally we have Hannah Roberts from 7B.”

Hannah felt sick. Lottie squeezed her hand and whispered, “Good luck.”

Somehow Hannah got to the front of the hall. She found Lottie’s friendly face in the crowd and fixed her eyes on it.

“‘The Promise’,” she announced. She took a deep breath.

And as soon as she began, the hall and the people melted away and she was back in the farmyard.

“All day, a driving, slashing rain

Swirls through the yard in clouds. Rain tips

From broken gutters, pours along the cracks

In ancient concrete, churns

With dung and straw and soil to form a paste

Of claggy, stinking, filthy clay-grey mud.

We stay inside. It’s better there. But he,

In mud-encrusted, tattered waterproofs,

Wind-whipped, head bowed against the gusts

That stab like knives of ice, trudges through mud,23

Buckets in oak-gnarled fingers, crimson-cold.

And in the barn, a slime-grey tangled mass

Lies in the straw. A steaming, rancid stench

Of rotten flesh. Twin lambs, too early born,

To be slung on the dung lump with the waste.

Outside, the silhouettes of hollow oaks

Darken and sharpen against the evening sky.

Impossible that brittle bare black twigs

Could metamorphose into fresh green life.

But spring is creeping upwards through the soil,

Along the roots and branches of the oaks.

Sharp silhouettes will soften into leaf

From tiny, tight brown buds. And April’s warmth

Will heal his winter-battered face again.”

Hannah’s throat was tight when she finished. She had been far away as she read her poem. She had forgotten all about the audience.

Now she risked a glance out across the rows of chairs.

She wished she hadn’t.

Because all she saw when she looked up was Danny Carr. He was leaning back on his chair and letting out the most enormous yawn.

She bent her head down and, cheeks burning, hurried back to her seat through the jagged applause.

Lottie squeezed her arm. “That was great, Hannah. You’ll definitely win.”

Danny leaned forward. “Nice one. You should 24have seen that judge’s face when you were talking about dead lambs. I thought she was going to puke.”

Hannah looked down at her muddy shoes. She wanted to curl up and disappear.

She sneaked a look at the judge and Miss Francis. They were talking in low, intense tones.

She should have written a prettier poem.

She should never have mentioned dead lambs.

Eventually, Miss Francis stood up and smiled. She thanked everyone for entering, and then she said, “It was very difficult to single out one poem among so many excellent entries, but our judge has chosen a winner.”

Monica Rowse stood up, smiling her benevolent smile, and started on another speech. Hannah’s stomach twisted into knots.

“And so,” she finished, “I am delighted to announce that the Walters Cup for Poetry is awarded to … Miranda Hathaway!”

Of course.

Miranda’s gang in the front row cheered.

Lottie put her arm around Hannah’s shoulders. “Yours was miles better. That judge doesn’t know what she’s talking about.”

Sweet of Lottie to say that.

But it didn’t make any difference.

Maybe Dad was right after all. Maybe her writing was just a pointless waste of time.

Chapter Four

Homework

Miss Francis walked over as they were stacking chairs.

“That was a wonderful poem, Hannah.”

Hannah stared at her.

“I think the judge’s taste was perhaps a little more … conventional, shall we say, but I have to say that, for me, yours was the one that stood out.”

Hannah stood there, trying to take this in. The Head of English liked her poem best?

“Do you read a lot of poetry?” asked Miss Francis.

“Yes, loads. I love Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney. I love that they write about the countryside in a real way, you know? Not all fluffy bunnies and chicks and daffodils, but mud and blood and death. Not that the countryside’s always like that, obviously. But it’s a mixture – sometimes it’s beautiful and sometimes it’s ugly. And that’s the point, isn’t it? Spring wouldn’t be so beautiful if it didn’t come after winter.”

She stopped. She was talking too much.

But Miss Francis smiled at her. “Yes, absolutely. 26And I’d love to see more of your writing, if you’d like to show it to me.”

“See?” said Lottie as they left the hall. “I said it was really good, didn’t I?”

Hannah was glowing. The Head of English liked her writing!

She turned left towards their form room, but Lottie said, “We have to hand in our maths homework, remember?”

Hannah’s hand shot to her mouth.

“Didn’t you do it?”

“I was going to do it last night, but the sheep got out again. Oh, no, Mr Nagra’s going to kill me. I promised I’d hand it in on time this week. He said he’d phone my dad if it was late again. Oh, I’m so dead.”

“Just copy mine when we get to the classroom. It won’t take long.”

Hannah breathed a sigh of relief. “Oh, Lottie, thank you so much. You’re the best friend ever. You can copy mine next time.”

“So,” said Lottie, “do you really think your dad will let us have the loft?”

The wonderful vision of the theatre flooded into Hannah’s head again. “Why wouldn’t he? He doesn’t use it for anything.”

“We need to ask him today, though. I’ve got to email the entry form to the festival people by tomorrow. And we have to put the name and address of our theatre on it.”

Hannah skipped with delight. “Can you believe 27it? We’re going to enter the Linford Arts Festival! We’re going to have our own theatre!”

“So can I come up after school? Will he be around?”

Hannah stopped in her tracks and her eyes lit up. “Actually, that’s perfect. He’s taking the Field Marshall to a steam fair today.”

“To sell it?”

“No, don’t be silly. He’d never sell it. To show it. The point is, he loves the steam fair. He stands there all day showing off his Field Marshall and all these old blokes in tweeds come up and admire it and ask him questions about it. He goes every year and he’s always in a good mood when he gets back.”

“Fantastic. So I’ll come up after school.”

Lottie pushed open the door of their maths room. It was also 8M’s tutor room and, since the sky was hurling sheets of rain against the windows, most of 8M were in there. They huddled in groups around the tables, chatting and texting.

Hannah did a quick scan of the room.

No. He wasn’t there. He must be off sick today.

Was she relieved?

Or disappointed?

It was so hard to tell.

There was a pile of 7B’s maths books already on the homework shelf in the corner. Lottie sat down at the empty table in front of the shelf and pulled her maths book out of her bag. She opened it to reveal a page of work so neat that it deserved to be blown up to poster size and displayed to the world right there 28and then.

Hannah knew as certainly as she knew her own name that every single answer was right. Lottie had never in her whole life got a maths question wrong.

Hannah opened her own book and wrote yesterday’s date at the top of a clean page. She started to copy the first question.

The classroom door swung open and cracked against the wall. Every head turned.

Hannah looked up and her stomach did a back flip.

Into the room sauntered Jack Adamson. And, if it were possible, he looked even more gorgeous than usual. His wavy hair was all messed up and he had a cheeky grin on his face.

“Better late than never,” grunted Danny, looking up from his phone.

“Yeah, well,” said Jack, rearranging his expression into one of deep sorrow. “It’s just, I was a bit upset. Family tragedy.”

Vishali Patel was sitting at the table next to Hannah and Lottie. Her eyes widened in concern. “Oh, no. What’s wrong?”

Jack gave a heavy sigh and plonked himself down in the chair beside Vishali’s. He looked deeply into her eyes. Something stabbed at Hannah’s chest.

“It’s my goldfish,” said Jack sadly. “He got run over.”

The room erupted into giggles. Except for Lottie, who raised her eyes to heaven. Hannah looked down at her feet so Lottie couldn’t see her smiling. 29

Vishali smacked Jack on the shoulder. “You pig. You really had me going.”

“Aw, sorry, Vish. Hey, you couldn’t give us a lend of the geography homework, could you? I was going to do it but my mum’s on a life support machine and I had to go and put another 50p in the slot.”

Vishali giggled. “Oh, go on then.” She fished in her bag.

“Thanks, Vish, you’re a lifesaver.” He winked at her. Hannah felt that stab in her chest again.

“Loser,” muttered Lottie.

Jack looked up and caught Hannah’s eye. Hannah felt herself going red. Jack grinned at her.

“Saw you all pedalling to school this morning, Roberts.”

Danny snorted. “What, in that skip they call a car?”

Jack turned to his friend. “Don’t be mean, Dan. Her dad built that car himself. It’s all made from bits that fell off his tractors. One day he’s going to put an engine in it, then they won’t have to pedal any more.”

Hannah put her head down to hide her smile.

“You’re not funny, Jack,” said Lottie.

“Shame you missed the poetry competition,” said Danny.

“Yeah, I was really upset about that.”

“No, really. It was hilarious. She did this poem all about mud and rotting lamb corpses. The judge nearly threw up.”

Jack nodded respectfully at Hannah. “I like your 30style, Roberts. There’s not enough poems about dead animals in the world, that’s what I say.”

Hannah was a mass of confusion. She bent over her maths book so that her hair curtained her face.

“It was really good actually,” said Lottie. “I bet you couldn’t write a poem to save your life. You probably can’t even write.”

“As it happens,” said Jack, “I wrote a poem this very morning. It was inspired by the tragic death of my only goldfish.”

The class giggled again.

“Huh,” said Lottie. “Sure you did.”

“Want to hear it?”

“No,” said Lottie.

“Yes,” said 8M.

Jack took out his English book, stood up and looked around the class expectantly. They all looked back at him. When Jack performed, everybody watched.

Hannah gazed at him adoringly. He was so good-looking. And so funny. How could Lottie not see that?

“‘Ode to my Goldfish’,” declaimed Jack.

Danny snorted.

Jack allowed a generous dramatic pause before continuing.

“Bubble, bubble, swim, swim.”

Another dramatic pause.

“Verse Two,” he announced. “Bubble, bubble, swim, swim.

“Verse Three,” he continued through the laughter. 31“Bubble, bubble, swim, swim.”

“How many verses are there?” somebody asked.

“Thirty-seven.”

“And they all go, ‘Bubble, bubble, swim, swim’?”

“Yep. Hey, it’s not my fault,” he protested, dodging a book hurled at his head. “Goldfish only have four-second memories. He really wants to say more but he keeps having to go back to the beginning.”

“Idiot,” muttered Lottie as Jack sat back down, ducking a blizzard of flying objects. “Honestly, I don’t know how you can like him.”

“I don’t like him!” said Hannah.

“Oh, come on, Han, you so obviously do. You go red every time he looks at you. And you’ve been in such a love trance that you haven’t even finished question one and the bell’s going to go any minute.”

Oh, my goodness. Lottie was right. Hannah pulled Lottie’s maths book closer to her and started scribbling furiously.

“What are you doing in our classroom anyway?” Jack asked Hannah.

He leaned his chair sideways and glanced at the two maths books open in front of her. “Ooh, what’s this? Copying homework? In Year Seven? Tut tut.”

Lottie leapt in like a lioness protecting her young.

“At least she had a proper reason, Jack. Unlike someone I could mention. So don’t you dare say anything.”

“Shut up, pudding head,” said Jack. “You’re not her babysitter.” 32

The door opened and Hannah looked up.

Oh, help.

Mr Nagra was heading straight towards them.

Hannah slammed shut the two exercise books spread out on the table. She slipped Lottie’s on to the top of the pile on the shelf. But what could she do with her own? All she had written was the date and half of question one.

“Just in time, you two,” said Mr Nagra. “Right, let’s have those books.”

He picked up the pile of books and tucked them under his right arm. Hannah hid her book behind her back.

Honestly, what was she – five years old?