0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

Astra is powerfully attracted to handsome Charles Cameron. But will the vengeance of Astra's spoiled cousin come between them?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

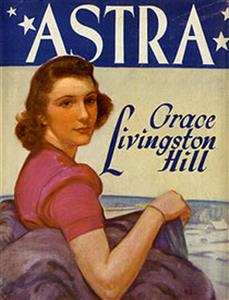

Astra

by Grace Livingston Hill

First published in 1941

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Astra

by

Grace Livingston Hill

Chapter 1

A few days before Christmas, 1940

It had begun to snow as Astra boarded the train just east of Chicago, but only in an erratic way. A few stray, sharp little flakes, slanting across the morning grayness, as if they were out on a walk, looking around. Not at all as if they meant anything by it. A few minutes later, after she was settled in her place in the day coach, one suitcase stowed in the rack above her, the other at her feet, she withdrew her gaze from the unattractive fellow travelers to look out of the window again, and the flakes were still wandering around, seemingly without a purpose. She watched one or two till they glanced across the warm windowpane and vanished into nothing. Only an idle little crystal drifted down from the eternal cold somewhere, and was gone. Where? Into nothing? What a lovely idle little life, thought Astra, as she settled back into her stiff, uncomfortable seat, with her head against the window frame and tried to turn her thoughts to her own perplexities. She was very tired, for she had gotten up early after a sleepless night and hurried around to get ready for the train.

And so, idly watching the aimless flakes of snow snapping on her consciousness from the windowpane outside, her eyes grew weary, her eyelids drooped, and she was soon asleep.

A little later she aroused suddenly as the conductor drew her ticket out of her relaxed grasp and punched it sharply, passing on to the next seat briskly. It came to her to wonder vaguely why he ever selected the job of conductor. To go through life in a dull train, far from home, if he had a home, and doing nothing but punching tickets. What a life! Only dull strangers, uninteresting people he didn’t know, to vary the monotony.

Idly she drifted away into sleep again, putting aside her own disturbed thoughts about personal matters, for she really was very weary. When she awoke again the snow was still coming down. The flakes were larger now, and more purposeful, as if they meant business.

She sat up and looked out. They were going through small towns and villages. People were passing along the streets with brisk steps, bundles in their arms. In marketplaces there were rows of tall pines and hemlocks displayed for sale, and a bright cluster of red and silver stars, holly wreaths, and Christmas trimmings.

Christmas! Yes, Christmas was almost here!

She drew a soft quivering breath of desolation. Not much joy in the thought of Christmas for her anymore! Going out alone into an unknown world, with very little money and without a job!

The train swept out of the town where it had lingered for a few brief minutes just opposite that market with its rows of Christmas trees, and then the increasing snow drew her attention. The flakes were larger now, and whiter, giving a decided whiteness to the atmosphere. The next small town that hurried into view ahead showed up a merry string of lights along the business street. They brought out the whirling flakes in giddy relief, as if flakes and lights were in league for the holiday season, bound to make the most of their powers.

People about her were ordering cups of coffee and eating ham sandwiches that were brought around in a basket for sale. Others were drifting by toward the diner car. But Astra wasn’t hungry. However, she bought a sandwich and stowed it in her handbag, against a time when she might feel faint and not be able to get the sandwich so easily. Then she sat back again, watching the twilight as it crept through the snowflakes. Gradually the landscape was taking on a white background from the falling snow, and soft plush flakes were melting on the windows and blurring into one another. It was becoming more and more difficult to see the landscape as it whirled by, to discern the little towns with their holiday trimmings, and more and more, Astra’s thoughts were turning inward to her own problems and her own drab life.

She had friends of other days, of course—friends of her childhood and young girlhood, friends of her mother’s and father’s, and she was hastening back to them. After all, it was only two years since she had left them and gone to live with Cousin Miriam, who had been almost like an older sister to her in the past when Miriam used to spend so much time at holidays and vacations from school and college with Astra’s mother.

But Miriam had married into wealth and fashion and was very much changed. The standards on which both she and Astra had been brought up were no longer Miriam’s standards. She laughed at Astra for continuing to uphold them. She told her that times had changed and one couldn’t continue to be dowdy and old-fashioned just because one’s mother was that way. One had to do what others did, in company, even if there were things called principles. It wasn’t done in these days, to have principles. One couldn’t “get on” and have principles. One had to smoke and drink a little. Everybody did. To “get on” was, in Miriam’s eyes, the end and aim of living.

Astra couldn’t get away from the thought of how ashamed her mother would have been of her cousin, for Astra’s mother had practically brought up Miriam from the time she was a schoolgirl of twelve, at least as much as one could do that important act within the limits of vacations and holidays.

In addition to Miriam there was Miriam’s daughter, Clytie, badly spoiled, and very determined in her own way, which was the way of a changing world that Astra did not care to adopt.

Astra had stood the differences as long as she could, and then during the absence of the cousins on a western trip in which she was not included, she had written a sweet little note of farewell and departed.

And now that she was on her way, she was tormented continually by the fear that perhaps she had been wrong to go. Perhaps she should have endured a little longer. But in a few days now she would be of age and would have a little more money to carry on quietly. To secure one of her mother’s old servants perhaps to stay with her, or something of that sort. It had seemed so reasonable and easy to make the transfer now when she was about to come of age. And when she considered returning before her cousins got back, or trying to live the life from which she had just fled, the latter seemed utterly impossible.

The twilight was deepening, and the snow outside the window was gathering thick and soft on the glass, obscuring the view. Suddenly the lights sprang up in the car and banished the gloom of the winter world, bringing out the faces of the tired, discouraged people, the grimy car, and the sharp outlines of the hard seats. All at once the world that Astra was starting out to conquer for herself loomed ahead unhappily, menacingly, with appalling unfriendliness. Suppose she shouldn’t be able to get a position anywhere? Suppose her small allowance should run out and she have nowhere to go? Suppose her father’s friends were dead or moved away? A lot of things could happen disastrously during a two years’ absence. Whatever could she do? Not go back to her cousin’s house! Never! She must find something to do. She could not go back to the cousins who would jeer at her and treat her with all the more condescension and find more and more fault with her.

“Oh God,” she breathed, “please, please find me a job! You have places for other people to work, couldn’t You find a little place for me? Couldn’t You please do something about it for me, for I don’t know how to do it myself. I haven’t money enough for very long. You know. Show me what to do.”

Her head was back against the seat, her forehead resting against the coolness of the window frame, her eyes closed. She could hear the soft splashing of the big flakes that were falling now, as she rode on into the whiteness of the winter night and prayed her despairing young prayer in her heart.

Then suddenly the door at the front of the car was flung open and a man’s voice spoke clearly with a young ring to it that must have appealed to all who heard it.

“Is there a stenographer here who will volunteer to take dictation of a very important document from a man who is dying?”

Astra sat up at once, stirred to instant attention, filled with a kind of awe at this strange, swift call from a man in distress. She was the kind of girl who was always ready to help anyone who needed it.

There were also two other girls standing, hesitantly, prompt and alert to answer a call from a good-looking young man anywhere. Yet they stood only an instant listening to his explanation, calmly chewing their hunks of gum. Then they slumped slowly back in their seats.

“Oh! Dying? Not me!” said one of them, pushing out her chin as if he had offered her an insult. “I don’t like dying people. Excuse me!”

The other of the two girls shook her head decidedly. “Nothing doing!” she said with a shrug. “I’m on a vacation, and I wouldn’t care ta handle a job fer a dead man!” Then they both giggled for the edification of the other travelers. But Astra walked steadily down the aisle to the young man.

“I am a stenographer,” she said quietly.

She had taken reams of dictation, the notes of her father’s lectures and articles; she knew she was master of the requirements.

The young man’s eyes appraised her with approval, and he said, “Thank you! This way please!” Then he turned and pointed the way through the next car, courteously helping her across the platform.

“The second car ahead,” he said. “He was taken with a sudden heart attack. Fortunately, there was a doctor at hand, and he is doing all he can for him, but the sick man is much distressed because he knows he may go at any minute and there are important matters that must be recorded before he dies. You—are not afraid?”

Astra looked at the young man gravely.

“Of course not,” she said quietly. “I’ll be glad to help.”

He looked his approval as they moved swiftly down the aisle and came to the small stateroom in the next car where the sick man had been laid.

He was lying in the narrow berth grasping for breath, the doctor by his side and a nurse preparing something under the doctor’s direction. The sick man looked at Astra with pleading eyes.

“Quick!” he gasped. “Get this!”

The young man who had brought her handed Astra a pencil and pad, and she dropped down on a chair by the bed and began to work swiftly, the young man watching her for an instant, relieved that she seemed to understand her job.

The sick man spoke very slowly, deliberately, his voice sometimes so low that the girl could scarcely hear him.

There were a couple of telegrams on business matters addressed to business firms, putting on record definite arrangements the sick man had completed during his journey. Then there was a briefly worded codicil to his will, concerning certain large properties the man had acquired recently which were to be left to his son by his first wife. This codicil was to be sent to his lawyer at once, observing all the formalities of the law. All this was spoken with the utmost difficulty, gasped slowly, detachedly, as his breath grew faint or his drifting intelligence faded and then flashed back again. It was heartbreaking, and Astra forgot her own perplexities in making sure she caught every syllable the troubled soul uttered.

When the dictation was completed the sick man sank limply into his pillow, relaxed for an instant as if he had reached the end. Then he roused again and feebly pointed at the papers in the girl’s lap.

“Copy! Quick! I—must—sign—”

Astra gathered her papers together and stood up with an understanding look in her eyes.

“Yes of course,” she said in a clear, businesslike voice. “If I only had a typewriter, it would take almost no time at all,” she added.

The young man stood at the door.

“Come right this way. I have a machine ready for you,” he said, and led her down the aisle to another car and into a small compartment where was a typewriter and plenty of paper.

“It will be necessary to have two copies,” said the young man. “Here is carbon paper.”

Astra sat down and went expertly to work, and in a very short time she had a sheaf of neatly typed papers ready.

The young man was back at the door as she finished.

“Fine! That was quick work. I didn’t expect you’d be quite done yet,” he said. “We’ll go right back. The doctor has given him a stimulant, hoping to make those signatures possible. We’ll have to be witnesses, of course.”

The patient lay with bright, restless eyes on the door as they entered, and a relieved look came into his face as he saw them.

The doctor and nurse arranged a bedside table, tilted so that the patient could see what he was writing, and they placed the papers one by one upon it and watched the trembling hand trace feebly the name that had been a power in the business world for many years.

It was very still in the little stateroom. Only the noise of the rushing train could be heard. Astra glanced at the windows, covered thickly now with snow, shutting out the darkness of the outside world, with only now and then a faint, fleeting splash of color—red or yellow or green—as the train flashed through a lighted town.

And now the signatures were finished, the last few strokes evidently a tremendous effort as the lagging heart sought to keep the muscles doing their duty to the end, and then the poor brain fagged as the last stroke was made, and the man slumped back to the pillow, the limp hand dropped to his side, the grasp on the pen relaxed, and the pen snapped away to the floor, its duty done.

The young man recovered the pen. Astra dropped down in her chair where she had sat for dictation and began to get the papers in shape for the witnesses.

The doctor, with his finger on the sick man’s pulse, was giving attention to his patient, the nurse removing the bed table, straightening the covers.

Then the sick man’s eyes opened anxiously, as if there were one more command he must give. His lips were stiff, but he murmured with a wry twist one word. “Witnesses!” He tried to motion toward the papers, but his hand dropped uselessly on the bed. He looked at the doctor pleadingly and the doctor bowed.

“Yes sir! I’ll sign as a witness!” Turning, he stooped over the little table that had been placed beside Astra and wrote his name clearly, hastily, on each paper. The sick man’s glance went to the others, and one by one they all signed their names: Astra, the young man, and the nurse. Then the sick man drew a deep sigh and closed his eyes with finality, as if he felt he had done everything and was content.

The doctor and nurse did their best, but a gray shadow was stealing over the man’s face. He scarcely seemed to be breathing.

Astra, after signing her name as a witness, gathered the papers up carefully, laid them together on the table, and sat there watching that dying face, a little at a loss to know just what was expected of her next. The young man and the doctor had stepped outside in the corridor and were talking in low tones. The nurse was mixing something from a bottle in a glass. Then suddenly the sick man opened his eyes and looked up, and his face was filled with anguish.

“Pray!” he murmured, almost inaudibly.

The nurse was on the alert at once with a spoonful of medicine.

“Pray!” she said snappily. “You want someone should make a prayer? Well, I’ll ask the doctor to get a preacher.”

She stepped to the door and murmured something to the doctor, but the sick man cast an anguished glance toward Astra.

“Can’t you—pray?” he gasped. “I can’t—wait!”

His breath was almost gone, and the girl sensed his desperation. Swiftly, she dropped back to the chair again and bent her head, her lips not far from the dying man’s ear, and began to pray in a clear young voice.

“Oh heavenly Father, Thou didst so love the whole world that though all of us were sinners, Thou didst send Thine own dear Son to take our sins upon Himself and die on the cross to pay our penalty, so that all who would believe on Him might be saved. Hear us now as we cry to Thee for this soul in need. Give him faith to believe in what Thou hast done for him. May he rest in Thy strength and know that Thou wilt put Thine arms around him and guide him into the Light. Give him Thy peace in his soul as he trusts in what the precious blood of Jesus has done for him. Make him know that he has nothing to do but trust Thee. We ask it in the name of Jesus our Savior, Amen.”

“Amen!” came a soft murmur from the dying lips.

Then suddenly a loud, disagreeable voice boomed into the solemnity of the little room, where the voice of prayer still lingered.

“Well, really! What’s the meaning of all this? George Faber, what are you doing in here, I’d like to know?”

Astra looked up and saw a tall, imposing woman, smartly turned out and groomed to the last hair. Lipstick and rouge and expensive powder combined to give her a lovely baby complexion that somehow only made her look older and very hard. She was looking straight at Astra with cold, hostile eyes.

Yet so sacred had been the scene through which Astra had just passed that she did not at first take in that this hostility was directed toward herself.

The doctor had suddenly arrived, with a warning hand flung up for silence, but the woman paid no attention and boomed on.

“I go into the diner to get my dinner and leave my husband in his seat because he said he didn’t want any dinner! Just stubbornness that he wouldn’t eat! And then I come back and find him gone! And when I at last track him down, I find him in bed with a whole mob around him! And this designing young woman—who is she?—whining around and putting over some sort of pious act. Who is she?—I demand to know!”

But the last of the question was smothered by the doctor’s hand firmly laid across the woman’s lips as he and the nurse grasped her arms and forced her out of the room into the corridor, closing the door sharply behind her.

After that things were a bit confused. The sick man’s eyes were closed. He looked like death. Had he heard that awful voice maligning him?

Astra stood at one side, the papers with the dictation grasped in her hands, her frightened eyes on the sick man. Was he living yet?

Then the door opened and the young man beckoned her to come out. The woman seemed to have disappeared for the moment.

The young man drew Astra over to an unoccupied section and made her sit down.

“Shall I take these papers for the time being?” he said, and she surrendered them thankfully. He slipped them inside his briefcase.

“Mr. Faber seemed to be anxious that no one else came in on this side. He told me that before I came after you,” he said in explanation of his care.

“Now will you sit here for a few minutes until I can scout around and find out the possibilities? I suppose these telegrams ought to get off at once. There’s a Western Union man on board. Just stay here and I’ll see what can be done. I won’t be long.”

He hurried away, and Astra sat there staring at the great white flakes that were coming down like miniature blankets lapping over each other on the windowpanes. The warm train seemed so protected from the darkness that had come down while she had been busy. There seemed a great quiet sadness all about her as she sat thinking of the little tragedy. She had a strange feeling that God had been in that stateroom while she had been praying for the dying man, and He had heard her prayer. She seemed still to hear the echo of that whispered“Amen!” as if it were the heartfelt assent of the man’s passing soul. And it seemed a strange thing that it had been so arranged that she should have been the one to answer that cry from a dying man.

She wondered, was he gone yet? It surely had seemed like the end. Her own sorrowful experience when her father died had taught her to know the signs. And it had really seemed to give him relief to leave those messages behind. She was glad she had been able to help.

Then she heard a door open sharply at the extreme other end of the car, and footsteps, silken stirrings, sounded down the corridor. Suddenly there was the smart lady coming stormily down toward her, battle in her eyes.

She sighted Astra almost at once and fixed her cold blue gaze upon her, coming on with evident intention to do her worst.

Now she was upon her, standing in front of her with the attitude of an officer of the law come to bring her to justice.

“Who are you?” she demanded, and her voice rose again. “And what were you doing in my husband’s stateroom, you shameless creature, you?”

Chapter 2

Astra looked at the woman with surprise, growing into dawning comprehension, and then a quick glow of interest.

“Oh,” she said pleasantly, “you didn’t understand what happened, did you? I didn’t go in there of my own accord. I was asked to go.”

“Indeed!” said the woman arrogantly. “Who could possibly have asked you to go? Who had a right to do so? Who are you, anyway?”

“Oh,” said Astra with a quiet calm upon her and the hint of a smile through the gravity of her expression, “I am just a stenographer they asked to come and take some dictation for a man who was dying.”

“Nonsense!” said the woman impatiently. “Dying! He’s not dying! He gets these spells. He’ll come out of it. He’s most likely out of it now. And who, may I ask, presumed to take my husband into a stateroom and bring a strange doctor and a strange nurse and stenographer and make such a to-do about it all? Why did anybody think he was sick?”

“I really don’t know, madam,” said Astra coldly. “I was asked to come, and I came.”

“Well, really! This is very mysterious! Who presumed to ask you?"

“The young man who was in there when you came. I don’t know who he is. He came into the other car where I was sitting and called out to know if there was a stenographer there who would come quickly and take some dictation.”

“Well, of all the absurd ideas!” said the woman, snapping her eyes at Astra. “Who is this young man? Some friend of yours?”

“No,” said Astra, and her own voice was somewhat haughty now. “I never saw him before.”

“What is his name?”

“I don’t know, madam. You’ll have to ask him.”

“Well, it shows what kind of girl you are, going off with a strange young man to take dictation from a stranger! Well, what important dictation did you take? Let me see the papers! I’ll take charge of them now.”

“I haven’t the papers, madam.”

“Where are they?”

“I don’t know. I presume they have been taken care of as your husband directed.”

“Well, what did the papers say?” demanded the woman.

Astra looked at her with wide, surprised eyes.

“Why, that wouldn’t be my business to tell,” she said. “A stenographer is only supposed to do her work and then forget about it.”

“Oh, really? And you have the impudence to say that to the wife of the man whose dictation you took?”

Then Astra saw the young man coming toward her, and she looked up with relief.

“I’m sorry,” she said quietly to the irate woman. “It was a matter of business, you know, sales he had completed on his trip, I think. I don’t suppose it would interest you. And I have not intended to be impudent. A stenographer is not expected to give attention and remember the matters which she transcribes, she is only a machine while she is at work. At least, that is what I have been taught.”

Then she rose and stood ready as the young man reached her side, and the woman turned and started at the young man, giving Astra opportunity to escape toward the door.

The young man soon followed her.

“I thought,” he said as he reached Astra’s side and opened the door for her, “that perhaps we could go into the diner and get some dinner together. There we could have an opportunity to make a few plans about those papers. That will give us comparative freedom from interruption. I don’t fancy having that woman interfering, do you? She may be his wife, but she has no idea what happened, and from what he told me, I don’t think he wanted her to have. He had evidently seen his son and had an interview with him. Now, you haven’t had your dinner yet, have you? Will you go with me?”

He led her into the dining car and chose a table where he could watch anyone entering at the other end and where they would be far enough from other diners so that their conversation would not be heard. After the preliminaries of ordering were over, he leaned across the table and began to talk quietly.

“Now,” he said with a pleasant, businesslike smile, “my name is Charles Cameron. My business office happens to be next door to the office of G. J. Faber, our sick man. I know him personally only slightly. We meet occasionally. By reputation I know him well. He is highly respected.”

Cameron studied the face of the girl before him as she watched him while he talked. He decided she was taking in every word he said and comparing it with her impression of the sick man.

The waiter arrived just then with their order, and there was no more conversation for a few minutes till he was gone.

“Mr. Faber got on the train at Chicago,” went on the young man, “with his wife and a lot of luggage. He had the section opposite mine. He looked up after he was settled and nodded casually to me, as he always does when we meet. After that, we didn’t pay any further attention to one another. His wife was occupying the center of the stage and there was no opportunity. I was reading. I dimly realized that they were having some kind of a discussion, though she was doing most of the talking, and presently she went off in the direction of the diner. That seems a long time ago to me now. But I fancy she took her time. And then, too, she would be one who demanded a good deal of service in a diner, which explains her long absence during our most strenuous time.”

The waiter came back to refill their water glasses, and when he left, Cameron went on.

“The wife hadn’t been gone but a very few minutes before Mr. Faber reached over and touched me on the arm. He said he was sick, would I help him? He wanted a doctor and a stenographer. That is how it all began. The porter said there was a rather famous doctor on board, and he brought the nurse. Now I ought to tell you that I’m afraid there is a little more involved in this than just copying those notes. We’ve probably got to appear before a notary and swear to all this, you know. That is, if he dies, and the doctor seems to think there is no hope for him. But I thought I had better prepare you for the next act. Are you game?”

He watched her somewhat anxiously, and she suddenly smiled.

“Of course,” she said gently. “Would it be likely to take long? But that wouldn’t matter. I was planning to stay in the city for a few days at least. And my time is not important just now.”

“Well, that certainly is accommodating of you. You know, of course, that this won’t be any expense to you, and there will be some remuneration for your services. Mr. Faber gave me money to cover all such items when he first asked me to help.”

“But I wasn’t expecting remuneration,” said Astra. “I was glad to help someone in distress.”

“Well, that makes it nice,” said Cameron, “but there will be remuneration. And now, may I know your name? It might be convenient, you know, before we are through with this business.”

“I am Astra Everson,” said the girl. “And perhaps I ought to tell you that I am not a regular stenographer. Although I’ve had good training, I have never done that work for anybody but my father.”

“I don’t see that that should make any difference,” said Cameron. “You evidently are a good stenographer. One could tell that by watching you work a few minutes. Your father is most fortunate to have such an able assistant.”

Astra flashed a pleasant look at him.

“Thank you,” she said gravely. “But my father died almost two years ago. I’ve been living with a relative since. But I’ve come away from her home now, and I’m on my own. I haven’t thought out my plans definitely yet.”

“Yes?” said Cameron. “Well, could you perhaps give me an address where mail would be forwarded to you?”

Astra thought for a moment and then gave him the address of an old friend of her father’s.

“I shall keep in touch with them,” she said, “and leave a forwarding address there if I should go away.”

“Thank you. I’ll be remembering that,” said Cameron. “I feel that you have done a great piece of work today. I doubt if there is another person on this train that could have covered the needs of that dying man as perfectly and comprehensively as you have done. I hesitate to speak of it, because I was not supposed to be in the room, and it seemed too sacred a thing for one to intrude upon. I mean your prayer. I don’t know a girl in my whole list of acquaintances who would have the courage to pray for that dying man, or would have known how, under such circumstances. Undoubtedly, some of my friends pray in private, or at least I suppose they do, but I wouldn’t be sure that one of them would have done it aloud or would have known what to say if they had tried.”

Astra lifted wondering eyes, as if to make sure he had understood.

“But, he asked me, you know.”

“Yes, I heard. And it certainly was a genuine request. I never heard such pleading in a human voice, only one word, but it told all his need. Such anguish in human eyes—dying eyes.”

“I know,” said Astra with a shaken voice. “I wished—someone else were there. I wished you had not gone out in the corridor. He needed some last message so much.”

“Well, I’m ashamed to say that I wouldn’t have been able to give that man such a message as you gave. It seemed—well—really inspired! You touched on so much. It was the kind of prayer that I would have liked to have prayed for me if I had been that man—a hard, lonely businessman who never had had time from making money to think about God or the beyond.”

Astra’s eyes were upon her plate, but she lifted them slowly as she spoke.

“I think,” she said as she looked thoughtfully into his eyes, “that when God sends a duty like that for which one is utterly unprepared, the Holy Spirit gives the words one should use, don’t you? I wouldn’t have known how unless I had trusted Him to do that.”

The young man looked at her in wonder.

At last he spoke, with awe in his voice.

“You must know God then very intimately, if you can expect a thing like that.”

There was a question in his voice, and his eyes were still upon her. She was almost at a loss just how to answer him. Was he a Christian, or not?

“Why,” she said with some hesitancy, “of course it is the privilege of all saved people to know God intimately.”

“Is it?” he said after a moment of silence. “I never thought about it in that way. I am a church member, since boyhood, but I never exactly thought of myself as saved. I—hope to be, of course.”

“But that is something you can be absolutely sure about if you have accepted Christ as your personal Savior,” said Astra. “We have God’s definite promise for that. ‘He that believethhath everlasting life, and shall not come into condemnation; but is passed from death unto life.’”

“Well, I’ve heard that verse, of course,” said Cameron, “but I never thought of it as being a definite personal assurance of salvation. Do you mean that if I have an intellectual conviction that Jesus Christ once lived on earth and died on the cross for men, that I have a right to feel that that covers everything? That I am saved through all eternity?”

“Oh no, I wouldn’t dare to say just an intellectual belief would save. It has to be an active belief, trusting in what He has done for you personally as a sinner.”

He studied her with interest.

“How did you come to the knowledge of all this?” he asked at last. “You must have had a remarkable father.”

“Yes,” said Astra, with a tender look in her eyes, “I did. He taught me to study the Bible.”

Then there came the old porter from the car behind, who touched Cameron on the shoulder. The young man looked up questioningly.

“De doctor say, will you please come to him. De old gemman seem to be dying, and de doctor needs you to send some telegrams an’ he’p make ’rangements.”

“Of course,” said Cameron, throwing down his napkin and springing to his feet. Then turning to Astra he said, “You’ll excuse me, I know. I want to help, of course. No, I don’t think it will be necessary for you to come. You had better go to your own car for the night and get a good rest after your strenuous evening. Besides, it will be just as well for you to avoid the unpleasant old lady. When I left the car, she was still storming all around the place, determined to discover what you had written. You had a reservation, had you not? Can you find your way? Shall I take you there?”

“Oh no, that’s not necessary. I can get back to my seat. But if there is any way that I can help, I’ll be glad to do it, even if she is unpleasant. Her words can’t hurt me.”

“That’s good of you,” said Cameron. “If there is anything for you to do I’ll send for you or come for you. But I’m sure it won’t be necessary. You had better have your berth made up and get some rest. Or had you a reservation? There will probably be plenty to do in the morning, and you need to get a good night’s sleep.”

“No, I didn’t have a reservation. It was late when I got on the train, and I didn’t bother to hunt up the conductor to get one. I can always curl up in a day coach and get a good rest.”

She smiled reassuringly, but Cameron looked determined.

“No, that’s no way to rest. I’ll speak to the conductor for you and send you word. But go on back to your seat now. Your baggage is there, isn’t it? I should have looked after that for you, but it slipped my mind. However, go back now and I’ll look after everything. If I find I can’t get away myself, I’ll send this porter. You’ll know the lady, won’t you?”

The dignified porter nodded his head.

“Yassir! I know de lady!”

Astra smiled, and the two men went on their way together, while she found her way back to her seat in the day coach, feeling a little as if she had been off the earth for a while and had suddenly been dropped back on her own again.

Her seat was there, vacant as she had left it. Her two suitcases were there, one on the floor, the other in the rack above. The two reluctant stenographers were curled into separate seats, sound asleep, one with her hat hiding her face, the other with her face in full view, her mouth wide open, audibly snoring. Astra half smiled as she passed them, glad that they were not awake. They looked to her like girls who would have asked a lot of questions, and she would not have wanted to answer them.

The windows were thick with snow now. There was no looking out on lighted towns, even if there had been any towns. They seemed to be going on endlessly into the night, and Astra was back where she had been several hours ago, looking into an unknown future, wondering what the next day, and the next, would bring forth in her life. Was she going to be sorry that she had left the shelter of her cousin’s uncongenial home? Was she just going into another more uncongenial atmosphere perhaps?

She was glad after a few minutes to see the kindly face and dignified bearing of the old porter coming down the car toward her.

“Yassym, miss,” he said importantly. “We have de berth for you now, three cars ahead. Dese yore baggage, miss? Just step out in de aisle. I’ll get it.”

With the ease of long accustomedness, he swung the suitcases out and started on. Astra was glad that almost everyone in the car was dozing or asleep and not interested in her going. She felt a sudden shyness after having been called out of there a few hours before in such a dramatic manner.

She was glad to arrive quietly where most of the berths were made up, a long aisle of drawn curtains, the people behind them asleep.

She found in her own section was a lower berth made up, the upper not even let down. She had a passing gratitude for the thoughtfulness of the young man who had ordered it.

Then the porter handed her a folded paper.

“Gemman send this,” he said.

Astra glanced at the note. It was a few words about where he would meet her in the morning.

She smiled at the porter.

“Tell him all right. I’ll wait there till he comes,” she said, and handed him a bit of silver.

Then she was glad to lie down and sink into a deep sleep that left her no opportunity to try and figure out the way ahead, nor even go into the way behind to see if she had done wisely in coming.

Chapter 3

If Astra Everson had not made up her mind that she simply could not stay in her cousin Marmaduke Lester’s house any longer, she would probably never have taken the definite step of going back to the old home to find her father’s friend, Mr. Sargent, and discover for herself just how her finances stood.