Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

From the Bram Stoker Award®-finalist and Splatterpunk Award-winning author of Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke, a grim yet gentle, horrifying yet hopeful tale of grief, trauma, and love. If you're reading this, you've likely thought that the world would be a better place without you. A single line of text, glowing in the darkness of the internet. Written by Ashley Lutin, who has often thought that, and worse, in the years since his wife died and his young son disappeared. But the peace of the grave is not for Ashley—it's for those he can help. Ashley Lutin has constructed a peculiar ritual for those whose desire to die is at war with their yearning to live a better life. Struggling to overcome his never-ending grief, one night Ashley connects with Jinx, who spins a tale both revolting and fascinating. This begins a relationship that traps the men in a tightening spiral of painful revelations, where long-hidden secrets are dragged, kicking and screaming, into the light. Only through pain can we find healing. Only through death can we find life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 235

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Praise for At Dark, I Become Loathsome

Also by Eric LaRocca and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Endnotes

Acknowledgments

About the Author

PRAISE FOR

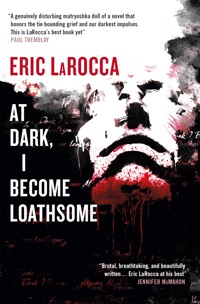

AT DARK, I BECOME LOATHSOME

“Brutal, breathtaking, and beautifully written, At Dark, I Become Loathsome is Eric LaRocca at his best. It broke my heart and put it back together again, leaving jagged little scars. LaRocca is a master at peeling back the layers and showing us true darkness and depravity, the loathsome monster hiding inside us all. I applaud him for his bravery, and you, dear reader, for yours.”

Jennifer McMahon, New York Times Bestselling author of The Winter People and My Darling Girl

“Imagine when literature had the power to be profane. Imagine reading Naked Lunch when it was first unleashed. Imagine no further. Eric LaRocca is this century’s William S. Burroughs. He is a Rimbaud abomination. His writing is akin to every ‘Season in Hell’. At Dark, I Become Loathsome is a literary ritual, an unholy evocation of those unsparing authors who martyred themselves in the name of transgressive literature. To read this book is to partake in the agony and ecstasy of our poetic saints . . . and to burn right alongside them at the stake.”

Clay McLeod Chapman, author of What Kind of Mother and Ghost Eaters

“Only Eric LaRocca can dig you a warm grave, luring you into its layered depths with a symphony of self-loathing, and make you never want to crawl out of the dark.”

Brian McAuley, author of Curse of the Reaper and Candy Cain Kills

“Terror, humor, humanity, lust, loss: at dark, everything, everything comes out. And Eric LaRocca is afraid of nothing.”

Kathe Koja, author of The Cipher and Skin

“A visceral, unflinching, and yet startlingly humane plunge into desire, depravity, and the essential loneliness of existence—this is a book that you won’t, and indeed, can’t soon forget.”

Kay Chronister, author of Desert Creatures and The Bog Wife

“With scalpel-sharp prose and an imagination bleak as a starless night sky, Eric LaRocca is the reigning king of uncompromising, decadent horror.”

Tim Waggoner, author of Lord of the Feast

“When people think of transgressive literature, they all too often think of it as an assault on the reader: external, aggressive, alienating. What makes LaRocca’s work so effective is not only how transgressive it is but how humane it is. These are not transgressions you can stand outside of. Instead, because of his skill reeling us into close proximity with the characters, the transgressions feel intimate, almost as if we were in the process of committing them ourselves. Which makes them all the more relatable, and all the more alarming.”

Brian Evenson, author of Last Days and Song for the Unraveling of the World

ATDARK,IBECOMELOATHSOME

Also by Eric LaRoccaand available from Titan Books:

Things Have Gotten Worse Since Last We Spokeand Other Misfortunes

The Trees Grew Because I Bled There:Collected Stories

Everything the Darkness Eats

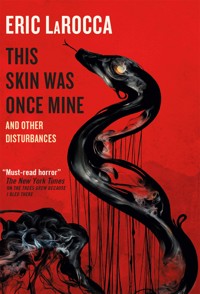

This Skin Was Once Mine and Other Disturbances

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

At Dark, I Become Loathsome

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781835411636

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835411643

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: January 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Eric LaRocca 2025. All Rights Reserved.

Eric LaRocca asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Daniel Kraus

“Some nights are made for torture, or reflection, or the savoring of loneliness.”

—Poppy Z. Brite, Lost Souls

“When we are born, we are magical and loving and full of wonder. But darkness and ignorance surround us at every corner. Until the day someone calls us a monster or a devil and we believe them.”

—Philip Ridley, In the Eyes of Mr Fury

“There is such peace in helplessness.”

—Kathe Koja, The Cipher

ONE

At dark, I become loathsome.

I wish there were a way to somehow soften the unpleasantness of it—to disguise some of the foulness, to hide some of the repulsiveness—but the horrible, wretched fact of the matter is that I become remarkably different when it’s dark out.

I don’t believe that I become another person, that I change entirely under twilight’s enchantment, but there is undeniably a shift in my temperament, in my demeanor, in my ability to think rationally and engage with others as I usually do in daytime.

I’m not prone to committing outrageously violent, unspeakable acts when the sun goes down, nor do I deliberately hurt anyone. It’s just that I become different at night. I think a lot of people are like that and don’t care to admit it. I believe most people change considerably when their environment shifts. Darkness is a substantial change to our environment when you consider the implications that nighttime brings. Some things can only happen at night for this reason. People’s inhibitions are lowered—their wants, their needs, their desires become paramount. That’s why I only make arrangements with my clients at night. Of course, that means they never know the true me, but that’s the way I prefer it.

It isn’t that I loathe my clients or wish them unwell; it’s simply that I don’t want to give too much of myself to them. That happened when I was more inexperienced in the process—when I was far more eager to serve some people’s capricious whims—and when I didn’t guard myself the way I should have. I think people should remain protected when nighttime approaches, almost as if twilight were a cancer that could rot us away until we were threadbare, tattered, and broken things, never to be repaired again.

At dark, I become loathsome.

I’m sure that some of my clients expect me to behave a certain way given the outlandishness of my appearance—the large metal piercings embellishing my nostrils and bee-stung lips, my forehead with its silver horn implants, my jewelry-decorated ears, bent and reshaped to resemble the ears of an elf.

At night, I become guilty of crimes I haven’t committed, much less even contemplated. I become a caricature of my former self—a creature to be persecuted, loathed, reviled, detested. At nighttime, I’m something to be tortured until condemned—someone completely and forever misunderstood.

I can’t pretend I didn’t summon some of these accusations, these charges, by the changes I’ve made to my appearance. But though humanity doesn’t escape us when it’s dark out, I’ve learned that human decency only exists when it’s convenient. The rest of the time, we’re feral creatures tirelessly spinning against the whitewater current of rapids bearing us down and carrying us toward an infinite black sea.

At dark, I become loathsome.

I think she can perhaps tell. Naturally, I’ve done everything I can to make certain she’s as comfortable as possible, given the arduous demands of the ritual. This is what she wanted, after all. But she still looks at me with a bewildered expression when I motion to the simple cedar coffin I’ve arranged in a shallow hole in the open field where we agreed to meet.

“Are you ready?” I ask.

She doesn’t answer, seeming much too preoccupied with her next destination—inside the coffin.

With the tenderness and care I deliver to all my clients, I lower her gently into the coffin until she’s lying on the cushions I’ve arranged there and is facing me. I set the oxygen tank beside her and instruct her how to use it before I strap the mask to her face. She looks at me, and for the first time in the few hours I’ve known her, she appears troubled, frightened, like a convicted adulteress being led to the public square where she’ll be stoned to death. Before I allow myself to think too critically about what I’m doing, I close the lid of the coffin and begin to shovel dirt on top. I wonder if she’ll scream. Sometimes they do. Sometimes they beg me or plead with me to stop. But they’ve signed the contract and I must finish the ritual or else they won’t achieve what they desire.

I don’t hear any sounds coming from inside the coffin as I ladle more dirt on top of the wooden lid. Finally, when the coffin has been fully covered, I toss the shovel aside and make my way toward my van, parked near the barbed wire–wrapped fence on the opposite side of the field. I grab my cell phone from the front passenger seat and thumb through my apps until I land on the timer. I set it for thirty minutes and watch as the clock begins to slowly count down. Shoving my phone into my pocket, I lean over the vehicle’s center console and open the glove compartment, where I keep a pack of cigarettes.

Tapping one out, I light the end and inhale sharply as I circle the front of the van and lean against the hood. The headlights shimmer across the grassy knoll ahead of me and reach the small skirt of tall grass that guards the distant row of trees where the forest begins. I squint, wondering if there’s someone, something, with inquisitive, bead-like eyes, hiding between the trees and staring back at me, straining to measure me just as much as I’m struggling to understand them.

At dark, I become loathsome.

I can’t help but wonder if whatever might be watching me from the distant trees can somehow tell—if they are keenly enough aware to know that I’m a different person at night. I’m something monstrous, something unspeakable, something appalling, something to hide away like a shameful secret. That’s what I am—a secret to be kept, away from everyone, in a dark room.

I wonder if the young lady I’ve buried—the one who had sought me out for my expertise, my skill at performing this ritual—if she thinks I’m something atrocious. The way she regarded me when I prepared the oxygen tank for her . . . her face filled with such loathing, such disdain for me and what I was about to do to her. I think of proving to her just how monstrous I can truly be. I imagine myself gathering the equipment I’ve brought, loading it into the back seat of my van, and driving off. I think of her growing confusion, her uncontrollable panic when she realizes I’m not coming back for her. I imagine her horror—her shock, her dismay—as the air thins inside the coffin and she realizes that she’s issuing her final breaths.

My own thoughts disgust me, repulse me to the point where I wonder if I’ll become too sick to carry on. Of course, people expect me to be a monster, but do I need to satisfy those expectations? Just looking at me, some might assume I would be the type to bury someone alive, to trick them into willingly climbing inside a coffin only to murder them. It pains me to think there are people who expect that kind of behavior from me because of what I look like.

I finish my cigarette, crushing the burnt end beneath my shoe and squishing it into the grass. I glance at the timer on my cell phone screen. After taking a swig of whiskey from the small canteen I left on the passenger seat, I meander back toward the grave. It’s at the center of the open field, the mound of fresh dirt piled like a makeshift pyramid. When the timer goes off, I snatch the shovel from the ground and start digging. The earth begins to swallow me as I scoop more and more dirt from the grave, piling the soil and debris to one side of the hole. Finally, my shovel hits something solid—the coffin lid.

On hands and knees, I clear the dirt from the coffin until it’s completely uncovered. With a trembling hand, I open the coffin and come face-to-face with the young woman I buried. Her eyes are wide; she stares at me with such shock, such amazement, as if I were a welcome trespasser on some private, ancient ritual. I peel the oxygen mask from her face and she inhales deeply, eyelids fluttering.

“Can you move?” I ask her.

She doesn’t respond. She seems enamored with the mere sight of me, her mouth curling into a smile. Given my appearance, it’s a look I don’t receive too often—a look of joy, euphoria, almost unimaginable longing. She releases soft whimpering noises as I kneel above her, one knee on each side of her torso. Her whimpers soon begin to weaken to sobs. I clear some of the wetness beneath her eye with my thumb. She regards me with such thankfulness that I scarcely recognize the woman I buried.

In an act of tenderness that shocks even me, I bend and kiss her forehead.

“Happy birthday,” I say.

She still hasn’t said a word, doesn’t seem capable of speech. She looks at me with a strange combination of bewilderment and delight that disturbs me.

Right now, this young woman doesn’t regard me as a monster. Instead, she looks at me as if I’m a sibling, a gentle steward, a devoted lover—perhaps even an immortal god to be adored, worshipped, and revered.

I don’t quite know how to react to her as she takes my hands and squeezes them with apparent thankfulness. I think I should perhaps tell her, but I don’t:

At dark, I become loathsome.

TWO

After I pull her out of the coffin, I tell her that she needs to rest for a few moments before doing anything else.

“You’re like an astronaut returning to planet Earth,” I joke to her.

But she doesn’t laugh.

Instead, she obeys without comment, sitting in the tall grass and inhaling and exhaling with obvious labor. I make a quick dash to my van and grab a bottle of water from the cupholder. When I return, my client is lying on her back, staring at the starless night sky—her eyes as wide as quarters and her lips moving with words I cannot hear.

There’s something terribly endearing about her—the way she smiles, the manner in which she regards me—and I think it’s such a pity I’ll never really know her. This brief encounter on the outskirts of our little Connecticut town will be our final contact. Perhaps it’s best that way. That’s how most of my clients prefer it, and I must confess I prefer a similar level of privacy.

She found me the way most of my other clients did, on an online message forum for those who consider themselves to be on the fringes of society: the outcasts, the miscreants, the derelicts.

Can you really change my whole outlook on life? she asked me over instant messenger one evening.

That is almost always the first question asked by those who are unfamiliar with the procedure. Granted, most people are unfamiliar with the ritual I created.

Now, I ask her, “How do you feel?”

At first, the woman doesn’t seem to quite know how to answer, as though she possesses the words but cannot properly arrange them to describe her experience.

“Like . . . a dragonfly crushed between two windshield wipers,” she says at last, her voice trembling a little.

I laugh.

At least she has a sense of humor about the whole ordeal, I think to myself.

Very often, those who go underground for the thirty minutes come back with a distinct surliness or a decidedly maudlin demeanor, as if I had threatened them in some way.

“That’s all?” I ask.

“And . . . like a wildflower growing on the moon. Does it always feel like that?”

I shrug. “It’s different for everybody.”

She doesn’t seem content with my half answer as she rolls her eyes. Without warning, she straightens and tries to get up. Almost instantly, her knees begin to buckle and a visible jolt of pain sends her flying back down like a balloon tethered to a wooden post.

“You’ll be weak for a little while,” I remind her. “Just try to be still.”

“How long was it?” she asks, her eyes tirelessly searching my face, seeking an explanation.

“Thirty minutes,” I say.

“Not years?”

“Was it what you had expected?”

Part of me is always curious to know how the clients react after the fact, after they’ve been interred, after they’ve been given exactly what they came for.

“I . . . don’t know,” she says, her eyes narrowing, genuinely perplexed by the question.

I pull my phone from my pocket and open the Notes app. I write down both of her descriptions, then ask, “Do you feel different?”

She laughs at me. “That’s a stupid question.” I keep typing as she continues, “I was just buried alive for thirty minutes. What do you think?”

My eyebrows furrow and my tone firms. “I have to ask. It’s part of the ritual.”

She blinks at me, seeming to understand.

“Yes. I feel different,” she tells me quietly.

I can’t help but wonder if she thinks I want to fuck her.

I don’t.

It’s not that she’s unattractive or displeasing to look at, but she doesn’t suit me, the same way that most women don’t suit me. The opposite sex has never really suited me, if I’m being totally truthful. They remain a mystery to me. Men too, for that matter. I’m incapable of charming men or women.

I know this question will be the most difficult to answer, but it must be asked.

“What did you think about?”

I watch as she shuts her eyes and tightens her hands into small fists.

“Where’s my purse?” she asks.

That’s not an answer, and I frown, displeased, but reply, “Still in the car, with all your other things.”

“Will you get it for me?”

I study her for a moment, wondering what she’s planning. Humoring her, I stroll back to our vehicles, open the back door of her car, and lift her pocketbook from the floor. When I deliver it to her, she immediately starts rooting around inside the small bag.

“What did you think about?” I repeat, phone once again in hand.

“My mother . . . finding me in the bathroom,” she says, pulling a small container, filled to the brim with little white pills, out of her bag.

“What did you see?”

The young woman closes her eyes, as if she had quietly been dreading the question, knowing full well I might ask it. Her lips quiver. She shakes her head, then opens her eyes; they are wet and shimmering.

“Nothing,” she says, staring blankly at me. “There was nothing for me there.”

I watch as she unscrews the cap of the small bottle and shakes the contents over the open grave. The pills scatter into the open coffin like the gemstones of a necklace torn from the throat of a dowager empress—a woman who had seen all the wonders of hell and knew keenly of the nothingness, the oblivion, that waited for her there.

* * *

*The following text is an excerpt from a large manuscript prepared by Ashley Lutin and concerns the details of his “fake death” ritual. It is understood that someone reading this particular section of text will be already familiar with the ritual in question.*

THE AFTERCARE

Just as there’s aftercare for rough sex, there’s a certain level of intimacy to be considered when conducting a ritual of this nature. Some clients prefer physical contact after they’ve been interred for thirty minutes. They prefer to be held while they openly cry, as if to know that another human cares for them and is monitoring their safety and well-being.

In the several months I’ve been organizing these “fake death” rituals, I’ve found that the level of aftercare for each client is highly dependent upon the client in question. Some prefer intense physical contact after they’ve been buried and will even petition the caregiver to engage in intercourse following their “reincarnation.”1 It is imperative that the caregiver not engage in sexual physical contact with the client as this would diminish the integrity of the ritual as well as the honor of the overall experience.

The aftercare of the ritual consists of three parts:

Begging

Borrowing

Stealing

I will go into careful detail of each of these subsections of the overall aftercare when tending to a person who has just been unearthed from their fake death.

“Begging” is the first stage of the aftercare program; it involves the caregiver making distinct and emotive supplications for the client to trust them and bask in their comfort. Of course, trust must be established well before this moment in the ritual; however, it’s imperative for the client to know that the caregiver is someone to be trusted.

“Borrowing” is the second part of the aftercare system. The term refers to the actions the caregiver must perform in order to properly care for their client. In this stage, the caregiver must borrow an artifact that has some sort of sentimental value to the client and utilize this prop to tend to the client’s needs. If the client does not supply an article to be used as a means of proper aftercare, then the caregiver must call upon their experiences when interacting with the client and perform to the best of their abilities.

Finally, “Stealing” is the third and final stage; it refers to the fact that the client always takes a little bit of the caregiver with them when they leave. Though the caregiver can do everything in their power to make certain that their emotions and personality are guarded and protected throughout the procedure, the client will typically draw something out of the caregiver and render them changed. Just as the client transforms throughout the ordeal, so does the caregiver. The caregiver must expect to lose something to each client and must accept this loss in advance in order to properly recuperate and move on from each ritual.

The steps in completing effective aftercare are fundamental to the success of the client and their caregiver. A successful aftercare denotes that both caregiver and client are forever changed by their interactions.

* * *

Though I invite the young woman to sit with me in my vehicle for an hour or so, listening to music and sharing a joint, she doesn’t take me up on the offer. Instead, she swiftly dodges behind her car, which is parked next to my van, and changes out of the white linen robe I brought for her. When she’s dressed again in the denim jeans and flannel shirt she wore when she first arrived, she circles the vehicle and makes her way back toward me.

She passes me the robe, which I stuff back into my rucksack. I return to the hole, dragging the wooden coffin out and dumping it in the tall grass nearby. When I’ve done that, I start shoveling dirt into the open maw that looks to me like the mouth of an ancient deity—a deity so reviled, so loathed, by their contemporaries that they were condemned to be buried in the earth.

While I do this, I watch the young woman fish inside her pocketbook. She pulls out a small wad of cash wrapped with a rubber band, walks over, and passes it to me.

I take it and shove it in my pocket immediately.

Then she surprises me once more: She offers me her hand. Naturally, I take it and squeeze it tight in an effort to let her know that the ritual is finished, it’s done—and she survived.

She leans in, pecking me on the cheek and whispering a muted “thank you” in my ear. Before I can say anything, the woman returns to her car and slides into the driver’s seat. I hear the engine, see the vehicle rock slightly as she puts it into gear. I recoil a little as the car lurches forward and heads down the small dirt roadway that stretches like a dark ribbon into the nearby trees. I watch her taillights flicker through the wooded thicket until they disappear, swallowed by oblivion.

Then I grab hold of the coffin and haul the thing back to my van, where I eventually load it into the rear of the vehicle. I push aside several blank canvases that are leaning against the back seat and draped with white linen. It feels unnatural to even look at my painting supplies—relics from my former life. In my absentmindedness, I knock over a small canister of paintbrushes, scattering them across the small area. Some brushes roll out of the vehicle and drop into the tall grass. I think about leaving them there. After all, it seems unlikely I’ll ever paint again. I had every intention of leaving that part of me behind.

I glance up at the night sky and notice the black velvet curtain hanging overhead like a fisherman’s net. There are times when it feels as though the dark could bore holes in me the size of quail eggs—gentle reminders that I am forever changed when twilight arrives. It’s strange to think that several years ago, I might have dragged the blank canvases out of the rear of the van and set up a small easel in the empty field. I might have wasted an hour or so capturing the surrounding darkness—the way in which the trees seem to bend out of respect for twilight’s charm; the stillness of the sky; and how everything seems to slow to a crawl when nighttime enchants the world. I can’t bear to think of taking the time to paint now. It pains me too much to consider. I once found peacefulness and tranquility in my artwork—the solitude of pushing everything away and focusing entirely on the way the tip of my paintbrush connects with the blank canvas. Now it seems like a doorway leading to a part of my life that’s been locked away, closed off, forever.

I load my other equipment into the van and slam the doors shut. I crawl into the driver’s seat and the motor revs sweetly when I twist the key in the ignition. I find myself leaning on the gas pedal with a sudden urgency—the same resolve that beckons all nocturnal beings to find themselves in the sanctity of the dark, to wander until daylight, to hunt under the cover of night in search of their true meaning.

THREE

At dark, I become loathsome.

It’s a thought that comes to me quite frequently and rather naturally—an insidious little insect coiling in the darkest corners of my mind like a tiny metal spring, a well-oiled crank that spins freely and poisons the area around where it’s been planted like a cancer, like a black root to spread further and further until my mind is as dark and as shiny as fresh tar.