Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: The Great Composers

- Sprache: Englisch

Welcome to The Independent's new ebook series The Great Composers, covering fourteen of the giants of Western classical music. Extracted from Michael Steen's book The Lives and Times of the Great Composers, these concise guides, selected by The Independent's editorial team, explore the lives of composers as diverse as Mozart and Puccini, reaching from Bach to Brahms, set against the social, historical and political forces which affected them, to give a rounded portrait of what it was like to be alive and working as a musician at that time. In this ebook Steen traces Beethoven's tumultuous life, buffeted by the violent cross-currents of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars which convulsed Europe from the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the 19th. Born in Bonn, Beethoven became a successful musician patronised by the aristocracy. Though scornful of social convention, he conquered Vienna, creating works which rewrote the rulebook for all the musical forms he touched. Irascible and argumentative, Beethoven was a troubled genius; frustrated by politics, exasperated by friends, foes, and family, and plagued by the gradual loss of his hearing which began when he was still in his 20s. While conflicts raged about him and within him, he constantly surprised people by doing the unexpected and staying fiercely independent. He was among the first to bring the piano to the fore rather than the harpsichord, as the larger sound could play along with the rest of the orchestra in a hall. Beethoven could always turn to his love of music even when ill-health led him to consider suicide, the wars devalued his earnings, and the love for his nephew Karl and the infamous 'Immortal Beloved' was never returned. Today he remains one of the world's best-loved composers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 92

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published by Icon Books Ltd,

Omnibus Business Centre, 39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP email: [email protected]

IISBN: 978-1-84831-799-4

Text copyright © 2003, 2010 Michael Steen

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Steen OBE was born in Dublin. He studied at the Royal College of Music, was the organ scholar at Oriel College, Oxford, and has been the chairman of the RCM Society and of the Friends of the V&A Museum, the Treasurer of The Open University, and a trustee of Anvil Arts and of The Gerald Coke Handel Foundation.

Also by the Michael Steen:

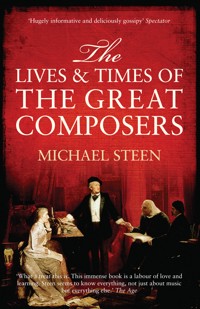

The Lives and Times of the Great Composers (ebook and paperback)

Great Operas: A Guide to 25 of the World’s Finest Musical Experiences (ebook and paperback)

Enchantress of Nations: Pauline Viardot, Soprano, Muse and Lover (hardback).

He is currently engaged in a project to publish one hundred ebooks in the series A Short Guide to a Great Opera. Around forty of these have already been published' and further details on these are given at the back of this book.

INTRODUCTION

Welcome to our ebook series The Great Composers, covering fourteen of the giants of Western classical music.

Extracted from his book The Lives and Times of the Great Composers, Michael Steen explores the lives of composers as diverse as Mozart and Puccini, reaching from Bach to Brahms, set against the social, historical and political forces which affected them, to give a rounded portrait of what it was like to be alive and working as a musician at that time.

In this ebook Steen traces Beethoven's tumultuous life, buffeted by the violent cross-currents of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars which convulsed Europe from the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the 19th. Born in Bonn, Beethoven became a successful musician patronised by the aristocracy. Though scornful of social convention, he conquered Vienna, creating works which rewrote the rulebook for all the musical forms he touched.

In this ebook Steen traces Beethoven's tumultuous life, buffeted by the violent cross-currents of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars which convulsed Europe from the end of the 18th century to the beginning of the 19th. Born in Bonn, Beethoven became a successful musician patronised by the aristocracy. Though scornful of social convention, he conquered Vienna, creating works which rewrote the rulebook for all the musical forms he touched. Irascible and argumentative, Beethoven was a troubled genius; frustrated by politics, exasperated by friends, foes, and family, and plagued by the gradual loss of his hearing which began when he was still in his 20s. While conflicts raged about him and within him, he constantly surprised people by doing the unexpected and staying fiercely independent. He was among the first to bring the piano to the fore rather than the harpsichord, as the larger sound could play along with the rest of the orchestra in a hall. Beethoven could always turn to his love of music even when ill-health led him to consider suicide, the wars devalued his earnings, and the love for his nephew Karl and the infamous ‘Immortal Beloved’ was never returned. Today he remains one of the world's best-loved composers.

BEETHOVEN

‘HE IS PERFECTLY entitled to regard the world as detestable, but that does not make it any more enjoyable for himself or anyone else.’1 This could be an exasperated adult speaking about a difficult adolescent; but it is actually the suave, sophisticated poet Goethe despairing about the behaviour of Beethoven. When, strolling together in a park, so the story goes,* they saw the royal family coming towards them, Beethoven pressed on: he went through the throng of Habsburg princes and sycophants like Moses parting the Red Sea. He then turned around and, much to his amusement, saw Goethe stand aside, his hat in hand and bowing obsequiously, to let the procession proceed.3

This incident and much of Beethoven’s life illustrate the extent to which, within a few years of Mozart’s premature death, a talented artist could assert his independence and yet survive.4 Although Beethoven often felt financially insecure, he did not have to hang about ingratiatingly and hope that some chamberlain would arrive with a bag of ducats. No longer was the musical composition on a shopping list of an aristocrat preparing the day’s entertainment, or ‘made to order’ to embellish the worship of God. This argumentative, ugly, pockmarked and slovenly man could now make a reasonable living from creating his own works of art. Music had become an object in itself, each work entirely the inspiration of the individual.

The audience could still be ignorant and abusive, as on the occasion when an empress dismissed a Mozart opera as ‘German hogwash’.5 Or it could even be intelligently critical. But gone were the days when a Medici prince could interfere and require Alessandro Scarlatti to make an opera nobler and more cheerful; or a Habsburg emperor could be concerned with the number of notes in an opera by Mozart.*

Beethoven, Goethe and the Royal Family

This new environment was attributable not just to the French Rev-olution which weakened the rigid framework of social structures. There was now an entirely new attitude towards art. Goethe caustically described the constraints by which artists had previously been circumscribed: ‘A good deal can be said of the advantages of Rules, much the same as can be said in praise of bourgeois society. A man shaped by Rules will never produce anything tasteless or bad, just as a citizen who observes law and decorum will never be an unbearable neighbour or an out-and-out villain.’ He continued: ‘On the other hand, the Rules will destroy the true feeling of Nature and its true expression!’7

So, while all great composers push out frontiers, Beethoven could break the rules in leaps and bounds. He remained fundamentally ‘classical’ in his style. Yet he surprised listeners of his First Symphony in C major by beginning it in F major.8 He began the Fourth Piano Concerto with the solo piano, a complete change from all previous concertos. He started the ‘Moonlight’ Sonata unconventionally with a slow movement.9 The final movement of the Ninth Symphony begins with a shocking chord. These are just obvious examples. Why did he do it? For his art. He went so far that his successors found that he had taken certain types of instrumental music almost to the limit, and he was virtually impossible to follow: Brahms just did not feel confident tackling a symphony until he was in his forties.10

Ludwig van Beethoven was born around 16 December 1770 in Bonn, the residence of the Archbishop-Elector of Cologne. A trivial consequence of the momentous French Revolution was that Bonn became an unbearable place in which to live. Beethoven moved to Vienna, a year after Mozart died. He withdrew increasingly into his shell as his sad life progressed, with his hopeless love life, his deafness and the family troubles with his nephew. His middle years, a period of great creativity, were accompanied by worries caused by the Napoleonic wars. By the start of the Congress of Vienna in 1814, other tastes and trends were developing, apparent in the operas of Rossini and heard in the new romantic sounds and textures coaxed out of the orchestra by Carl Maria von Weber.

At the end of his life, Beethoven lived in self-inflicted squalor, apparently drinking a bottle of wine with each meal.11 Rossini was so appalled when he saw him that he tried fundraising to help him, but got no support. People gave Beethoven up as a lost cause. But, in those last years, he wrote the Ninth Symphony. He seems to have thrown down the gauntlet to the next generation, almost saying: ‘try beating that!’12 It was a long time, if ever, before anyone did, or could.

BONN

We start far from Vienna. Beethoven’s grandfather, the son of a baker, was choirmaster in a church in Louvain, close to Brussels, where the family had earlier been involved in the lace business. Archbishop Clemens-August of Cologne invited him to travel 100 miles to Bonn and join the court music staff. He rose to become Kapellmeister, in the year that the archbishop died, nine years before Beethoven was born. This appointment was the kind of prestigious position which Leopold Mozart craved for himself or his son.

The highly cultured Archbishop Clemens-August was the brother of the Elector of Bavaria who in the 1740s briefly interrupted the Habsburg succession and became emperor. The archbishop resided in Bonn, well away from the Free City of Cologne, with whose burgers he had a very shaky relationship. He built himself several palaces, including a large ‘pleasure’ palace in nearby Brühl. This had a magnificent rococo staircase, and, in the garden, a summerhouse called the ‘Indian palace’ even though its style was Chinese. He enjoyed falconing, riding on his English hunters and being entertained by his jester. He also played the viola da gamba. There is a picture of him at a masked ball in the 1750s with the musicians working away in two bands on either side.13 (See colour plate 10.)

This relaxed and cultured life was spent against a background of rising prosperity.14 The agricultural revolution caused a considerable boom in property values. There were improvements in diet and hygiene, with a relatively low incidence of disease. The population was growing fast. There was, however, unemployment and vagabondage. France, increasingly unstable, was not far away.

The Kapellmeister’s son, Beethoven’s father, sang in the choir. He married, beneath his status, the widowed daughter of the head cook in one of the palaces. He took to drink and it was an unhappy marriage. Beethoven’s mother, who was never known to laugh, regarded life as ‘a little joy – and a chain of sorrows’.15 They had three surviving children, first Ludwig, then Caspar born in 1774, and Johann born two years later.

Beethoven was born at the back* of a modest house in the Bonngasse, a few yards from the market place and the gate leading out to Cologne, some sixteen miles away.16 In later years, he was unclear of his exact age. He was probably born on the day before he was baptised, 17 December 1770. At any rate, baptism had to take place within three days of birth. Around sixteen months earlier, Napoleon had been born in Corsica.