1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

Beautiful, young Eden is left alone to fend for herself after the death of her beloved father. When her own greedy cousin and aunt attempt to steal the precious inheritance her father has left her, Eden is aided by the handsome, young lawyer Lance Lorrimer.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

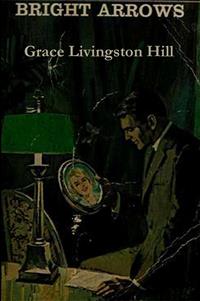

Bright Arrows

by Grace Livingston Hill

First published in 1946

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Chapter 1

Eden was sitting in the library of the old house where she had lived all her life. She was going over some papers in the big library desk. Her father had asked her to give special attention to them as soon as she would get home from his funeral service and be alone.

She had eaten quietly and conscientiously of the delicious supper that the devoted sorrowing servants had lovingly prepared for her. She had tried to keep a cheerful face during their ministrations and then had told them that she wouldn't need them anymore tonight and they must go to their beds and rest, for they had had a hard day. They had blessed her for her thoughtfulness and gone off to finish the few remaining household duties. Then they went silently to their rooms.

At least they had seemed to go, though they had not all gone to sleep. One of them did not even go to her room but was still alert for Eden's movements. The old nurse, Janet, who had been a part of the household ménage ever since Eden was born, did not even pretend to retire. She merely sat down in the servants' dining room and waited with a listening ear for her young lady. Her sharp bright eyes were hiding quick tears that she had not dared to shed before the others, and her kindly old lips that carried and would cherish to the end a Scotch accent from the old country were quivering with pain for the young girl left so alone in the world that had always been so satisfyingly filled with the presence of a tender father. Tabor, too, was sitting in the upper hall within hearing. So Eden was not really alone.

But Eden, having waited for this moment ever since her father had breathed his last on earth, thought she was alone now. She drew a sigh of relief and went over to the desk, taking out the small key that hung on a slender chain concealed about her neck.

It seemed almost as if her father had a rendezvous with her. She knew he had planned it during those last few days of his illness, after his accident, when he knew that his hours were numbered. It was the thought of this last farewell message from her father that had kept her up during the hard hours after he was gone. It was as if she were under orders and had not time to mourn for him yet, because he had left her something to do. He had said it would be something that would make it easier for her to go on.

Eden was very young to have to meet a crisis like this: the shock of an accident that resulted in the death of her only near and dear one, from whom she had almost never been separated. For she could scarcely remember her mother. Her father had been both mother and father to her. With old Janet to minister to her bodily needs, Eden had lived a happy, carefree life.

And so she sat alone, with old Janet out beyond hall and pantry and kitchen, on sorrowful, unsuspected guard.

Eden fitted the small key into the lock of the drawer to which her father had often directed her attention, turned it, and opened the drawer. Catching her breath a little, as one who understands a momentous thing is about to happen, she looked within.

And there, right on the top, was a folded paper bearing her name, in her father's beloved hand. For an instant it almost seemed as if she were looking upon that dear dead countenance that they had just laid to rest in the old cemetery. And then she remembered what he had said to her about this moment, and how when she unlocked that drawer she would find his last words to say good-bye and comfort her.

She closed her eyes for a brief instant and then put out her hand for the paper and drew it toward her, handling it as one touches a very precious treasure.

Softly, carefully, she unfolded it. It was not long but very clearly written, somewhat like the letters he had written her during his few brief business absences from home, but her eyes lit with pleasure as she recognized the old sweet greeting "Dear little lass." That had always been his dearest way of addressing her, even since she had grown into lovely girlhood.

She held the paper closer and settled back to draw comfort from her father's last words. There was an earnest look of eagerness upon her young face.

It was just at that moment that the door opened silently and someone came into the room. He stepped so inaudibly that at first she did not sense his entrance.

Then suddenly with an inner sense she realized that she was not alone, and looking up she saw him.

He was a handsome young man with a very engaging smile, nicely camouflaging a flippant sneer on the lips that were not turned to gentleness.

She had not seen him for three years, but she had never liked him. As a child she had been afraid of his cruel jokes and petty torments. When her father found it out, he removed her from his vicinity, taking her far away with himself on a journey till the obnoxious boy and his still more unpleasant mother had moved to a far city, with other interests.

He was not exactly a relative, just the son by a former marriage of a woman who had married her uncle a few years before his death. But he called himself her cousin, though it was not a blood relationship.

And now suddenly he was standing in the doorway looking at her with that gloating glitter in his eyes, masked by his old insinuating smile. How did he get in? The servants had locked up for the night. The night latch was on the door always. He had no key, and never had had one. Something cold and frightening clutched her heart.

For an instant they surveyed each other, and then the young man spoke:

"Eden! You lovely thing! You are more stunning looking than ever! I certainly am glad I came!"

Eden lifted her chin haughtily, and there was no answering smile on her young lips. She tried to summon all her self-possession and spoke in a voice of cool distance.

"Oh, you are Ellery Fane," she said.

"The same," said the young man, his hand on his heart and bowed low. "I am flattered that you remember me. And now that I am recognized, may I sit down? For I have something to tell you. I won't interrupt you long for I see you are going over important business papers. I'll be glad to help you if you think you are equal to doing them tonight after such a strenuous day as you must have had."

Eden suddenly remembered the dear letter she held in her hand, and with a quick motion she lowered the pages out of sight down in her lap. Then with swift, stealthy fingers, she folded the letter softly and slid it into the drawer, snapping the drawer shut and turning the key softly. Her experiences in the past with this slippery, would-be cousin had proved to her that nothing precious was to be trusted in his sight. Instinct had taught her this from her first knowledge of him when she was a mere child.

So, as he talked on with his insinuating voice tuned low, obviously on account of her recent sorrow, her fingers were swiftly at work extracting the little key and folding it close in her hand. Then she lifted her eyes haughtily to meet his insinuating gaze. "Thank you, I do not need help," she said coldly. "I feel that your coming, especially so stealthily and at this time, is an intrusion. But since you are here, what is it you want? I am in no need of help at present, and certainly not from you, when I remember under what circumstances you left this house last, at my father's request."

"Oh, now Eden, you're surely not holding that against me. I was merely a boy then, and I did make a mistake or two in my accounts at the bank. Of course, I've learned better now, and I suppose I ought to be grateful to your father for being so severe with me. It taught me a much-needed lesson. I've forgiven him long ago, of course, and started out to be a real man, the kind of man he wanted me to be. I've been studying high finance and am really an expert now, and I felt it was not only my duty but my pleasure to come and offer you my advice and skill in settling your estate. Of course, you are inexperienced, my dear, and I have an idea there will be many things about business that will be most puzzling to you. I'll be glad to put my financial knowledge and abilities at your disposal. I have several letters with me that will show you I am all that I say in these lines and certainly will be greatly to your advantage to have my advice."

Eden's voice was still cool and quiet in spite of her mounting anger, and she looked him in the eye steadily.

"That will be entirely unnecessary," she said coldly. "Such matters have all been attended to satisfactorily, and I have no need for advice. My father arranged everything for me before he left me."

"Yes, of course, I understand he would," soothed the honeyed voice. "He was always kindness itself and thoughtful, most thoughtful, for the welfare of others. But, my dear, I had not been in his bank long, even when I was a mere lad, before I knew perfectly well how unworldly he was, and how almost criminally ignorant he was of the best ways of managing a fortune and making the most of what he had, you know. As I began my studies and went on to wider knowledge, I kept looking back to what I knew of your father's business matters, and I knew what advantages he was missing by some of his oddly fanatical ideas about right and wrong that were simply nonsensical. And so I thought that it was my duty to come and tell you what I had learned in the world of finance and offer to set matters right for you, so that you might become almost fabulously rich in your own right. It will merely mean straightening out a few matters and exchanging some of your father's foolish investments before it is too late."

Eden, white with anger, rose from her chair, the little key clutched tight in the palm of her hand, the other hand leaning hard on the edge of her father's desk, her eyes flashing indignation.

"That will be all I care to hear," she said freezingly. "You can go now. I certainly want no help from you ever, in any way!"

Eden in her excitement did not realize that her fingers had automatically touched the little switch on the edge of the desk by which her father had often called for the old butler to do some errand for him. But suddenly the bell responded quickly through the silent house, making the unwelcome guest start in surprise and look cautiously around. That bell was something he had not known about, as it had been installed after he had left that part of the country. But Eden was so coldly angry now that she paid little heed to the bell. Besides, she thought that the servants had all gone to their rooms and were probably asleep. And she was not really afraid of this would-be cousin, anyway, just furious at his insufferable impudence toward her wonderful father. She felt that she could handle this situation herself. She would let him know that he was not wanted.

But the young man sat, still watching her intently.

"You don't understand, my dear! I mean all this in utter kindness. That is why my mother and I talked it over and decided that she and I would give up everything else and devote ourselves to you. Mother will arrive on the early train in the morning. She had to come from the far West, you know, and could not get here in time for the service today, but we talked it over on the telephone and arranged it all. Mother is coming here to live with you and chaperone you of course. You could not think of living here alone. It would not be respectable. Your father would never approve of that, I'm sure, and so it was up to your nearest relatives to come to your rescue----"

"Stop!" said Eden, tense with anger now. "I do not wish to have either you or your mother here, and besides, I have other arrangements----"

"Oh, really? Who is going to stay with you?"

"I don't wish to discuss the matter with you, either now or at any other time. My affairs are my own, and you have nothing to do with them. If you will leave at once, that will be all I shall ask of you."

The door into the hall had opened so quietly that neither of them realized that there were two other people standing in the room. It was the old butler who spoke firmly--his old voice sounded almost as young again as when he first began to serve his beloved employer.

"You rang, my lady," he said, standing at attention, with even his white gloves on his hands, giving an air of formality to his hastily donned uniform.

And just a step behind him, to one side, stood old Janet, her eyes wide and angry, her lips shut thinly and her hands folded flatly across her stomach in her most formal servantly humility, just as she had been accustomed to serve all her life.

The young man stood up, startled into embarrassed awkwardness for an instant. But he quickly rallied to what he called his "poise"--though there had been others who called it merely "brass"--and smiled an ingratiating smile.

"My word!" he said with a note of forced delight in his voice. "If there isn't dear old Janet. Alive yet! I remember how I used to delight in her gingerbread and chocolate cakes. And old Tabor, as faithful as ever. Say, this is a wonder. Eden you ought to--"

But Eden was talking in a clear, firm voice that cut like a knife through Ellery Fane's paltry prattle.

"Yes, Tabor, I'm glad you came. Will you kindly see this person to the door, and make sure that every door and window is carefully locked? And Janet, could I have a cup of tea?"

"Oh, but I'm not going out again tonight, Cousin Eden. I had planned to stay here all night. Didn't I tell you? You see, my mother is expecting to arrive here in the morning, and I thought we could talk it over and settle about our rooms--" But Eden spoke coolly and firmly again.

"No," she said forcefully, "you are not going to stay here tonight, and your mother is not coming here tomorrow. If you know how to reach her on the train, you had better wire her when you get to the station. It will not be convenient for me to have either of you stay here at any time. You had better go now, Ellery. I wouldn't like to have to call the police." The young man grinned impudently, as if it were a joke, but Tabor announced carefully:

"I've already called them, my lady! Your father made me promise to do so, if ever there were intruders--and I think I hear the police car at the door now."

"Thank you, Tabor," said Eden pleasantly, as if he had just announced friendly callers. Ellery saw by the set of the girl's shoulders and the lifting of her head that this was no joke. And without further adieu he turned to the hall door.

"Oh, well, if you feel that way about it," he said and vanished into the dimness of the dark hall, retrieving his hat and coat from a chair near the front door and pausing only to shout back: "I'll send you a card with my address, and anytime you need me you can send for me. I'm sorry you took it this way when I merely intended to help you. Good night."

So the unwanted caller left the house, even as Mike McGregor, the big policeman, entered the kitchen door. Eden stood quietly until she heard the front door shut and Tabor, after a short conference with Mike, returned to the library again. Then Eden slowly sank into her chair and dropped her face down on her folded arms on the desk. It was then that old Janet noticed that her nursling's face was wet with tears.

Quietly Janet slipped over and put a tender arm around Eden's shoulders.

"There, my little one," she said tenderly, smoothing the soft hair and patting the beloved shoulders. "How ever did that little rat get intae the hoose, I'd like tae know? I didna sight him at the service. He surely wouldna have had the impertinence tae coom openly. He allus useta work on the sly everything he did. He's not tae be troosted."

Then Eden lifted her tear-wet face and smiled.

"It's all right, Janet. It just upset me for a minute, but I'm glad it's over. And now, Janet, I think we had better keep this room locked, at night especially, because I don't like the idea of anybody being able to steal into Daddy's special room where he kept all his important things."

"Of coorse not, my wee lamb. We'll see tae thet right away," said Janet with a look toward Tabor.

"Yes, my lady," said Tabor capably. "And I'll have my word with the police to keep an eye on the place. In fact, I'm not sure but they intend to anyway. Your father may have mentioned it to McGregor when he was in to see him the other day. I thought as much for the answer he gave me when I spoke with him earlier this evening."

"Oh!" said Eden, looking startled. "But Father did not know where Ellery was, I'm sure. I knew he distrusted him, but we haven't heard from him since Father sent him away that time he made all the trouble for him at the bank. I shouldn't think he would dare to come again."

"That rat would dare onything," said Janet. "He's just been bidin' his time till there wasna onybody tae stop him. But don't ye worry. We'll see thet you're looked after."

"Why, I'm not worrying, Janet." Eden gave a vague little smile. "Only it was so dreadful to have him come in just when I was reading some last words from Daddy. Janet, I think I would like to take that second drawer up to my room. It's just letters, nothing really valuable except to me, but I wouldn't like to think of anybody like Ellery getting his hands on them."

"Of coorse not, my lamb. We'll take it right up tae yer room, an' I'll be sleepin' across the hall the night. Tabor will make oop his bed at the end of the downstairs hall, so ye'll be weel guarded, blessed child!"

"Oh, I'm not afraid, you know, Janet. But it will be nice to know you are near at hand. It is lonely this first night of course."

"Is it this drawer you want, Miss Eden?" asked Tabor, stooping to lift it out. "But it's locked."

"Yes, Tabor. Here is the key."

The man unlocked the drawer and drew it out.

"Is this the only one you want, Miss Eden?" he asked.

"Yes, I think so. Wait. None of the rest are locked. I'll see if I need others."

Swiftly she drew them out one at a time and glanced over the orderly contents.

"No, they are just routine things. Records, receipts, things that aren't very important." She closed them all and they started up the stairs, Tabor carrying the drawer and leading the way.

"Just put it down on the table by my desk," said Eden, "and thank you, Tabor. Now don't you two worry any more about me. I shall be quite all right, and I hope you won't lose any more sleep over prowlers. I'm quite sure Ellery Fane is the only one who would dare, and I think you thoroughly scared him off with your promise of the police."

"Right you are, Miss Eden. I'm positive you'll be entirely safe from any intruders from now on."

So the two servants were presently gone, and Eden locked her door and sat down to the reading of her father's letter, entirely assured that this time she would not look up to see Ellery's hateful eyes looking at her.

Sitting there in her own pretty room, in the luxurious chair that had been her father's gift on her last birthday, with all her pretty belongings about her, she could take a deep breath and really enjoy this last little conversation that her father had prepared to help her through the first hard evening after he had left her finally.

And so she began to read:

Dear little lass:

I promised you a last few words, so you could feel this first night that my love is still with you.

Because I have felt for a long time that you had missed the most beautiful thing out of your little-girl life, when your mother was called away, I have been casting about in my mind to find something that will partly make up for it. So I am now leaving you a packet of her own letters, which have for years been the most precious possession I owned and which nobody else but myself has ever read. Of course, I have told you a great deal about your dear mother, but even at its best the telling of a thing is never as good as the thing itself. Just hearing about what a mother you had could never be like growing up from childhood under her loving care. It is for this reason that I have left you her letters, that you may gather from them the atmosphere of the home into which you were born and really sense what a wonderful mother you had.

We talked a lot about you before you came, and afterward before she went away. You have a right to know what we said, and how we loved you, and what we hoped for your future. You will gather much of that from these letters, which are now yours, dear lassie. Don't weep when you read them. Just be glad to know we are safe with our heavenly Father, who is always watching over you.

Good-bye, little one, till we meet in heaven, and don't forget we'll be counting on your coming Home when your work down here is done.

Your loving father,

Charles Hamilton Thurston

Eden did not weep as she read the last words and let her eyes trace the precious familiar signature with a tender glance. But her cheeks were flushed, and there was a wonderful light in her eyes as she lifted them for an instant to look into a far distance, as if she were trying to send a smile beyond the gates of heaven to let her father know that she was being true to her promise that she would not let herself grieve for him.

A great swelling of her heart came as she folded up her father's letter and slipped it inside her blouse just over her heart. It seemed to her when it was there that she could feel his dear hand resting on her head, his voice telling her to be strong and not to think about her disappointments, but just trust and not be afraid.

Then half shyly she put out her hand to take the first letter of her unknown mother, whom she could scarcely remember, except as a sweet presence; she was always smiling. How glad that mother must be now that her dear husband had come to be with her in heaven. But it was all so vague. Did people live and feel and think and rejoice in heaven as they did on earth? Sometime when she found some very wise person who had studied about heaven she would ask about that.

Then her glance came down to the letter, as she took it out of the delicate envelope and scanned the beautiful writing. Oh, she had seen her mother's writing before of course. There was a lovely little white book, her own baby record written in this same charming penmanship, but somehow this was different. The book was a formal record with an occasional little merry account of some quaint child saying or bright idea.

But this letter was different. It was going to be like listening to her darling mother talking with her precious father.

"Dear Charlie."

The words thrilled the heart of the young girl, and for the first time some faint realization came to her of what it must have been to her mother to be in love with her father, as he must have been when he was young. Then she settled down breathlessly to read that sweet wonderful letter, the first real love letter that Eden had ever read. Oh, she had read love letters in novels of course, just fiction. But this was real life. This love letter had been lived, and by special dispensation was so linked to her life that she had a right not only to read it but to cherish it as a very part of herself.

Breathlessly she read the lovely girl-thoughts. More beautiful than all the dreams of romance that had ever visited her imagination--waking or dreaming.

On she read through the sweet impassioned words, which grew only more tender and delicate in expression as she went from one charming letter to the next. Reading a rare continued love story, through the first days of the beautiful courtship and on to the wedding day.

Then came a letter that told of a visit to relatives. It was most enlightening--Aunt Phoebe in a pale gray silk with blush roses in her little gray bonnet tied under her sweet little trembly chin. Eden remembered her only as a little old woman with tired eyes and skin like old parchment and a way of falling asleep in her chair. Grandma Haybrook with snapping black eyes that couldn't brook a fault in any but herself. She almost laughed aloud as she read about Uncle Pepperill, who would continue to take a pinch of snuff, even at a wedding.

There were fewer letters after that, save now and then a note written just for the joy of saying, "I love you." For she sensed that the two were continually together now, seldom separated except for a day or two occasionally for some business reason. But ever was that perfect flow of harmony and love in the very atmosphere, even of the brief silences between the letters.

There were little notations on the envelopes to mark these absences of letter. One read: "The first letter after Eden was born, while I was absent for a day at a banking conference."

Eagerly she opened that letter and found a wee snapshot of herself as a tiny baby, and a tender line:

I never knew or even dreamed what it would be like to have a little soul entrusted to our care! And to think our little Eden has such a wonderful father! I shall ever thank God for that! Oh, how can we ever hope to find a man as good as you, my beloved, as fine and strong and tender, and worthy to marry her? We must ask God Himself to prepare one for her.

It was just then that Janet's quiet footsteps came down the hall with a tinkle of silver and china from the tray she carried. She tapped softly at Eden's door, and Eden was suddenly recalled to the present from a very faraway past that represented her own beginning on the earth.

"Yes, Janet, what is it?" said Eden quickly.

"It's joost a wee drap o' tay an' a scone, my lambkin. Ye mustna make yersel' sick wie yer grievin'!"

Eden sprang to the door and let in her faithful friend.

"But I'm not grieving, you dear faithful friend," she said, taking the tray from Janet's eager hands. "But the tea smells good, and I really believe I'm hungry. Thank you, Janet! But you didn't need to worry about me. I have been having a wonderful time reading these letters that my father prepared for me for this evening. Letters from my own dear mother, Janet. See what pretty writing. And they are wonderful letters. Someday I'll read you some bits of them, especially those about my coming. You were here before I was, Janet. You knew my mother."

Janet stooped and looked sharply at the envelope Eden held out.

"Aye! Weel, I knew yer dear mither, my lambkin. An' thet's her writin'. I had several letters from her mysel', afore I came tae her while I was still in the auld country."

"Oh, did you, Janet? How nice. You never told me about that."

"Didna I tell you? Weel, ye were a wee mite, an' ye missed yer momma somethin' terrible. I didna wantae worry ye. And noo, ma bairnie, let me holp ye tae undress an' get intae yer bed. It's verra late, an' ye've had a hard day."

"No, I want to finish reading the rest of the letters," said Eden, looking wistfully toward the drawer beside her that still had more letters remaining.

"Why not let thim remain until the morn?" asked Janet practically. "Ye're lookin' verra tired, an' I'm quite sure yer feyther would advise thet."

Eden looked up and drew a long breath.

"Why, yes, I suppose Daddy would tell me to go to bed now. But it's been so wonderful to read letters from my own mother to my father, and to think he planned for me to read them now so I wouldn't feel so lost and alone."

"Yes, my bairn. He was a wonnerfoo feyther, an' she were a rare mither. Ye're greatly blest thet ye had them, even though ye air lonely the noo. But noo, let me brush yer hair for ye and get ye tae yer cooch. There'll be people coomin' in the morn perhaps, an' ye'll wantae be good an' rested tae meet them."

"Yes, I suppose you're right, Janet," said the girl, yawning wearily.

And soon Janet had her tucked comfortably in her bed, the light out and the door shut for the night. So thinking the pleasant thoughts about those letters, as her thoughtful father had known she would do if she read them before she went to her bed, she soon fell asleep.

Then the faithful Janet went quietly to her bed, and Tabor, on his makeshift bed across the library door, planned to be quietly alert to any sound.

So the moon rose, then sailed behind a cloud, and later drew heavier storm clouds about itself and slipped down its way to rest also, and the world was very dark.

Then when the night was at its darkest, a dim figure stole across into the deepest shrubbery at the side of the Thurston house and disappeared near a little-used window of the old library. But the family slept on, and not even Tabor with all his wakefulness heard a sound.

In the morning, however, when Tabor opened the shutters and dusted the room, he found the other drawers in the master's big desk had been thoroughly searched, the contents stirred up and everything left in heaps!

He studied the whole situation thoroughly and then went to the kitchen telephone and called up the police station. It was early and no one upstairs was stirring yet. This was something that must be settled without the young lady's knowledge, if possible. He had promised his beloved master that he would guard Miss Eden as his own.

So Mike and Tabor went into the library and examined everything very carefully and very silently. Then all the papers were put back, the drawers locked, and they went around searching for the place where the entrance to the house had been made. They found it soon enough in the long window on the side patio that opened into the library. It was always kept locked. Ellery must have been the intruder and had probably unfastened the window as he stood by it during the last brief altercation before he left.

A few questions Mike asked of Tabor, and then he took himself away to start a search for Ellery Fane.

Chapter 2

Quite early the next morning Lavira Fane alighted from a Western plane, took a taxi from the airport to the railroad station, and after a refreshing cup of coffee and a pile of well-buttered toast with jam, boarded the train for Glencarroll, the city suburb where the Thurstons resided.

Finding no chauffeur to meet her, no taxi at that early hour in the morning, and not even a station agent whom she might blame, she walked with angry, disapproving strides up to the house, reflecting on her hard lot. She did not spend much thought on her lazy son for not attending her, for well she knew his ways. He had probably been up late the night before and was now sleeping the sleep of the shiftless. That was the way she had brought him up. Why should she blame him?

So she blamed other people for whatever he had not done, and assuming that Ellery had told Eden that she was coming, she blamed Eden for not having sent her chauffeur to meet all trains until she arrived. Hence she stalked along growing more and more irate as she drew nearer to the house, which seemed to have moved to a far greater distance from the station than she remembered.

In due time, however, angry and tired and thinking incessantly of the fine breakfast she anticipated that would be served her soon after her arrival, she marched up the stately stone steps and rang the bell.

This was while Tabor was conversing with the policeman, and Janet had not yet come downstairs.

Tabor heard the bell and frowned, glanced at his watch, and frowned again. The policeman gave him a quick glance and said he had better leave.

"Wait!" said Tabor. "I don't know who that would be unless it's that pest of a mother of his. He said she was coming this morning."

"Mmmmm!" said the policeman in an undertone. "You go ahead. I'll stick around."

So Tabor went reluctantly to the door, and silently Janet began to descend the upper stairs.

Thus reinforced, Tabor opened the front door.

"Well! So you did decide to come to the door at last, did you?" blatted the undesired guest. "I shall certainly report this to the family. Are you the same servant that was here the last time I visited?"

Tabor met this tirade with stern countenance.

"Whom did you wish to see, madam?" he asked, in his most butlerish tone. "What is your errand?"

"Errand!" sneered the would-be guest. "I've come to stay. The family must have known I was coming. Stand aside and let me come in. I think it was most unfeeling of them not to have met my plane at the airport, they with their chauffeurs and butlers and other servants!" She fairly snorted out the last words, but Tabor stood immovable.

"Madam, I'm sorry, but I was told not to let anyone in until further word, and we are not disturbing the lady of the house at this hour. She has been through a heavy strain and needs the rest."

"Lady of the house!" snorted the irate Lavira. "Who's that? You don't mean that conceited Janet with her weird Scotch lingo, do you? Because if you do, I'll have you know that no person like that can keep me out. I belong to the family!"

"Yes, madam, that may be so, but you see I have my orders, and I am not to go beyond them."

"Why, you unspeakable outrageous fool! The very idea of your daring to keep me out of this house! I insist that you take my name up to Eden or whoever she has put in charge of the house. If you don't do so, I'll push by you and go right upstairs to her room myself. I simply won't be treated this way, when I've only come to be of service here, and I'm practically being turned out of the door. You go at once!"

"No, madam. I have been told not to disturb Miss Eden on any account. Perhaps you do not know, madam, that there has been a death in the household, which has made it very hard for everybody, and we are doing all we can to give Miss Eden a chance to rest. In fact, her father, Mr. Thurston, asked me a few hours before he died to especially guard her from all intruders these first few days after he was gone, for he knew they would be more than hard for her."

"But this is ridiculous!" sputtered the woman. "I shall appeal to the authorities!"

Then suddenly Mike stepped into the picture.

"Just what is it you wanted to appeal to the authorities for, madam? I belong to the police force, and I have been asked to look after the comfort of this house. Suppose you come with me and we can talk it over."

Mike was enveloped in a brusque politeness, and his sudden authoritative appearance so startled the woman that she fairly gasped.

"Oh! A policeman!" she exclaimed. "Why, what has happened? Are things in such a bad shape here that they have to be guarded by a policeman?" she questioned, yielding to the firm pressure on her arm and authority of the law, as she backed down the steps and was propelled down the front walk and out to the street.

"Why, yes, madam," Mike said in a well-guarded whisper. "Last night after they had all retired and the house was carefully locked, somebody broke into the library and went through the late Mr. Thurston's desk and all his private papers!"

The announcement was made solemnly and filled the woman with awe.

"How--how perfectly terrible!" she exclaimed. "Of course, I didn't know about that. No wonder they were all so upset. But, you see, I'm one of the family and came here to help. I ought to go right up and comfort Eden."

But the hand of the law was still firmly upon her arm, and she did not go back. In fact, the alarm that this big Mike had suddenly raised within her was on the increase. She felt she should learn more about this supposed robbery that the man had been looking into. She must find out if her son had been caught in any such mistaken escapade. It would not be beyond his powers to try something like that, she knew. And it was all right, of course, if he found such measures necessary to carry out his plans. He and she had hoped to be able to work quietly from inside the house as members of the family. But anything was all right if he could get away with it, and so far he had always got away with it. Still it was rather frightening to think that there was a possibility that this time he might not get away with it.

She looked up pleadingly to Mike's stern face, with slippery unmotherly eyes.

"I really ought to go right away to Eden. She will wonder why I didn't come."

Mike looked down at her with wise, penetrating eyes.

"What did you say your name was, madam?"

"Fane," said Lavira eagerly, "I'm Mrs. Lavira Fane. And I got word--that is, I had the notice of the death, and I started right away to come, for I knew the dear departed man would have expected me to be here at once. I took the first plane and came right out here as quick as I could."

"You say your name is Fane? I see." He took out his notebook and flipped over the leaves with one hand. "Fane. Yes, Fane. Have you any relatives in the city or nearby by the name of Fane?"

A quick wary look came into the woman's eyes as she met the stern gaze of the policeman.

"Relatives? Oh no, none by the name of Fane. That is, no relatives at all in this part of the country except the Thurstons. You see, my name is really Thurston. I was a widow with one son and married a brother of the deceased, Mr. Thurston, so my name really is Thurston, and I certainly ought to go right back and be with Eden. It is my duty, you know."

But Mike McGregor walked steadily on, with his grasp still firm on the woman's arm, and suddenly he looked down into her shrinking, frightened eyes.

"Your son's name is Ellery?" he asked, quite casually, and pierced her through with those eyes that did not flinch.

"Why, yes," she simpered, trying to hide her astonishment. "Did you used to know him when he was here before? He was only a child then. I never heard him speak of you. He'll be here in a day or two, I guess. He had some business matters to settle up before he left the West, but he'll be coming on soon."

"Your son is here now," said the policeman calmly. "He must have arrived sometime yesterday, or perhaps earlier, but he is here now."

Lavira gave him a frightened glance, and he could see that her lip was trembling.

"But how would you know that?" she asked, trying to appear casual. "Where is he? I want to see him at once!"

Mike paused beside a big red police car and opened the door.

"Get in," he said coldly. "I will take you to him."

Lavira turned toward the car and suddenly caught her breath, stepped back a pace, and looked the bright red car over.

"But I can't get into that car," she said haughtily.

"Why not?" asked Mike sharply.

"But a bright red car like that! It looks like a police car!"

"It is a police car. Get in!"

"But I can't ride in a car like that! I never was in a police car in my life! I couldn't endure to ride in that. I would be ashamed all the rest of my life. I couldn't get over it."