Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

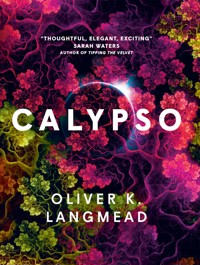

"Ambitious and immersive...an elegantly told meditation on how we can't leave ourselves behind." -Esquire Magazine - The Best Sci-Fi Books of 2024 A ground-breaking, mind-bending and wildly imaginative epic verse revolution in SF. A saga of colony ships, shattering moons and cataclysmic war in a new Eden. Experience the Hugo Award and BSFA award-nominated, truly unforgettable lyrical eco-fiction masterpiece, for fans of Kim Stanley Robinson, Adrian Tchaikovsky, and Jeff VanderMeer. Rochelle wakes from cryostasis to take up her role as engineer on the colony ark, Calypso. But she finds the ship has transformed into a forest, populated by the original crew's descendants, who revere her like a saint. She travels the ship with the Calypso's creator, the enigmatic Sigmund, and Catherine, a bioengineered marvel who can commune with the plants, uncovering a new history of humanity forged while she slept. She discovers a legacy of war between botanists and engineers. A war fought for the right to build a new Earth – a technological paradise, or a new Eden in bloom, untouched by mankind's past. And Rochelle, the last to wake, holds the balance of power in her hands.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 211

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Acknowledgements

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Calypso

Print edition ISBN: 9781803365336

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803365350

Broken Binding edition ISBN: 9781835410554

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: April 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Text © Oliver K. Langmead 2024

Illustrations © Darren Kerrigan 2024

Oliver K. Langmead asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

ROCHELLE

SIGMUND

CATHERINE

THE HERALD

The Calypso is a grand cathedral;

When the sun is out, a hollow eclipse,

And after dusk, a glittering circlet,

Crowning the dark heavens; crowning the stars.

She is ordinary to my children;

Another satellite like our bright moon.

They were born and raised beneath her shadow,

And they will feel her absence when she leaves.

Benson collects patterned, coloured pebbles,

Ordering and categorising them

By which he judges worthy of keeping

And taking home as precious mementos.

Ciara creates castles in the gold sand,

Digging rivers and moats for the warm sea

Washing in waves over her feet and hands,

Erasing her fledgling kingdoms quickly.

I tell them to be careful, to stay close,

To make sure they avoid the jellyfish,

And let me know if they need more sunscreen.

All the things I think a mother should say.

I will never see my children again,

At least in this life. I will leave them soon,

I will sleep, and when next I awaken,

They will have lived their lives and passed away.

This holiday, to the Caribbean,

Is my way of trying to fix myself

In their memories, so that when they die,

They will know to wait for me in heaven.

I have been blessed enough to give birth twice,

And now I must pass that blessing along.

When I wake next, I will be a midwife,

Because the Calypso is expecting.

The Calypso will soon be a mother.

She is ready, and expecting to birth

Skies, and rivers, and trees, and animals.

The Calypso will birth a whole new world.

The Calypso feels like a new nation.

The crew are so young, it surprises me

That they have learned enough to keep us safe;

To navigate the perilous expanse.

I have always admired the stellar maps

The same way that I admire works of art;

All those curving lines, by which gravity

Informs flights. There are no straight lines in space.

Most of the engineers have chosen Earth

To look down upon, but I choose the stars,

As if I might catch a glimpse, in the dark,

Of glittering Luna, or distant Mars.

“Is this your first time off world?” asks Sigmund.

I don’t think he’s ever spoken to me

Before, and I’ve never seen him up close.

He looks much older than in the posters.

I am so nervous that I spill my charts

And our skulls nearly meet as we gather

The clear plastic sheets – a muddle of stars

And the elegant routes plotted through them.

I am clumsy in the new gravity

Of the Calypso, but so is Sigmund.

We lean up against the viewing window

And laugh together. He sounds nervous too.

“She will take some getting used to, I think,”

He says. “Is this your first time, too?” I ask.

“No. I’ve taken trips to Mars three times now.

She wears her green coat well, these days. Come see.”

Doctor Sigmund leads me to his office

By the hand, and I can feel him trembling.

There is a large brass telescope set up

And he bids me to see Earth’s greatest work.

In the dark between the stars I find Mars,

Her moons, all the shining ships in orbit;

And in a crescent of sunlight I see

A mirror of Earth: green and blue and white.

“Life, in abundance,” I say, and notice

Sigmund smiling in pride. He is old, yes,

But I think that his eyes are still youthful,

Set in among the deep lines of his face.

“Why do you think I chose you?” asks Sigmund.

“I’ve been wondering about that,” I say.

The rest of the engineers are different:

They don’t have the same kind of faith as me.

“You are my golden compasses,” he says,

And I don’t know what he means, but I smile.

“You must have read my articles,” I say,

“My research on colonial ethics.”

“I’ve read everything you’ve ever written.

You are an able theorist, Rochelle,

And I look forward to debating you.

I asked for you because we disagree.”

“About what?” “About almost everything.”

Sigmund leans, looks out through his telescope.

“You will be a voice of dissent, I hope.

You will have the courage to tell me ‘no’.”

The noise of the new crew echoes loudly

Through the corridors of the Calypso,

And I find myself wordless – uncertain.

“Thank you,” I tell Sigmund, eventually.

I go out among the crew, and they sing

Songs about hope, about leaving Terra,

And I sing with them, and help where I can,

Because when I next wake, they will be gone.

I try to learn their faces and gestures,

So that I might see some semblance of them

In their descendants – the remnants of them

Passed down through the years and generations.

Soon, myself and the other engineers

Will go to our sarcophagi and sleep,

And God willing, we will wake and look down

Upon the face of a barren new world.

There is a kind of cleansing ritual

And we perform it alone, or in groups,

Undressing and washing away the Earth,

Rubbing the sacred oils into our skin.

When we are cleansed and ready, we’re led through,

Unashamed to bare all before the crew,

Because we will never see them again.

They sing what sound like hymns, or lullabies.

I go to my chamber, my small alcove,

Where awaits my bespoke sarcophagus,

Its smooth hollow the height and breadth of me.

There, I go down on my knees. One last prayer.

Today, I do not ask for anything.

I am simply grateful, and give my thanks

For the world I leave behind, its people,

Who, together, dreamt the great Calypso.

When I stand, the other sarcophagi

Are dark, their owners already asleep.

I am the last to leave the Earth behind.

A congregation of crew watch me rise.

They help me into my sarcophagus,

Smiling, reflecting the hope filling me

Like the preserving fluids through my veins;

Needling and burning and making me sleep.

Before the sarcophagus lid closes,

I think one last time about my children.

I hope they remember to wrap up warm;

It will be winter soon, and cold outside.

An eternity in the dark. Then, light.

The light is small, and red, and far away;

An indistinct glow against the abyss.

I reach out for it; traverse the expanse.

The sarcophagus lid trembles open

And I am resurrected – sliding free,

A mess of stinking sacred oils and limbs,

Heaving preserving fluids from my lungs.

There is more dark here, only dim white glows

Illuminating the mausoleum.

The other sarcophagi are open,

Vacant; each hollow an empty un-man.

I am a newborn without a mother,

No cat tongue to lick me clean, no towels

To swaddle me and hide my nakedness;

Nobody to witness my helplessness.

After the fluids are gone from my lungs

And all that was in me is out of me,

I breathe and breathe until the trembling stops

And try words – cries for aid that go unheard.

I haul myself up to my new fawn feet,

Wait for my blurred vision to stop whirling

And go among the dark sarcophagi,

Searching for anyone, for anything.

The lights above the lockers are all out

So I fumble in the darkness for mine,

Opening door after door and finding

That they are all still full: contents unclaimed.

I drag clothing so ancient it crumbles

Between my fingers from the apertures,

Then give up, and stumble for the showers;

Another dark space, lit by tiny glows.

The controls don’t produce any water:

There is a dry groaning from the bulkheads.

I pull open cupboards, and there, at last,

Find vacuum-sealed towels, untouched by time.

I shiver, cold, wiping the sacred oils

From me, recovering from the stupor

Of reawakening, trying to think

About where the engineers might have gone.

Wrapping towels around myself, I return

To the lockers, and for the second time

The fact that they are all full frightens me;

Why has nobody claimed their belongings?

I find my own locker at last; the clothes

And books and mementos ruined by time.

Only a single object is untouched:

One of Benson’s pebbles, from the beach trip.

I hold the pebble tight, then, in a surge

I throw open all the lockers, and spill

Scraps of tarnished cloth and crumbling papers,

Sifting through to find something I can wear.

At last, I find a vacuum-sealed package;

The only engineer with the foresight

To know what time would do to our treasures.

I curse our collective naivety.

Inside the package are clothes and letters.

I pull the trousers and shirt on – too big,

But a comfort against the emptiness.

The letters, I slip into a pocket.

There is a pair of plastic sandals too,

And I wriggle my cold toes into them,

Thinking about the beach; the sandcastles,

And the sunshine, and the coloured pebbles.

Gripping Benson’s pebble tightly, I go

To the door leading out of the chamber

I have slept in for decades – centuries.

The power is out, so I haul by hand.

The corridor is bright. I shade my eyes

Against the glare flooding through the window.

The dimmers have activated, but still

The white crescent glows, strong enough to burn.

I tremble, feel myself drop the pebble

Before the sight of that crescent brightness,

My fright washed away in its blinding white,

Blinking, trying to make my eyes adjust.

Unable to look at it directly,

I observe through the corner of my eye

That dawn out there, and feel my heart lifting

In awe, and in gratitude at the sight.

All those curved lines the navigators drew

Through stars and centuries brought us to this,

So that we, reawakened, may look down

Upon the face of this barren new world.

The echo of my footsteps herald me,

But I notice no stirring at the sound.

The Calypso’s darkened lengths are empty,

Brightened only by the crescent sunrise.

I am dwarfed by her cavernous hallways,

Designed for the milling of millions,

And shiver in a temperature set low

To compensate for their collective heat.

There should be a thriving nation singing

Songs celebrating the light-years conquered

To bring the Calypso all the way here.

But there is no nation. There is no crew.

Dim terminals provide basic functions,

Like light controls. The comms have been severed,

As has access to the Calypso’s logs;

She has been made to conserve her power.

I stare down darkened tramway corridors,

Hoping to glimpse some signs of life elsewhere,

But all is still, all is quiet and dead.

The cold air tastes metallic and sterile.

At a cafeteria, the taps work,

And I drink until I feel waterlogged,

Gasping and raising handfuls from the sink,

Splashing the chilling liquid on my face.

I wonder how many tongues have tasted

These gulping, recycled mouthfuls before

They trembled from the tap and into me.

These same droplets, used again and again.

There is evidence of the lost nation:

Dents and scuffs and scraps of ancient wash-cloths,

But where they might have gone, I find no sign.

I wander on, searching for anyone.

The doors to the gardens have been locked up,

But I haul at the manual controls

Until some weakness gives way to my strength

And the humidity within breaks free.

These gardens were vibrant, I remember:

So colourful it was almost dazzling.

The only colour left seems to be green;

A kind of thick vine smothers everything.

I wade through swathes of vines with small relief

At having found something alive on board,

Until I am lost among them, sweating

Profusely in the tropical climate.

Between waves of heat I glimpse somebody:

An unclear silhouette among the vines

That I fear might be a trick of the light.

I call out to them, stumbling through the green.

The figure approaches, is a person,

A real, breathing, laughing human being.

“Look at it all!” she cries, raising the vines

With trembling hands, her tight grip triumphant.

“I’m so glad to see you,” I say, smiling

At the way she gathers armfuls of vines

And waltzes with them, swaying and swooning,

Until she trips and tumbles, still laughing.

“I didn’t think for a moment,” she says,

Breathless, “It would do so well. I made it

Asexual, robust and virulent,

And it’s exceeded all my wildest hopes.”

Though her face is flushed, pupils dilated,

I still think that I might recognise her.

“You’re the bioengineer? Catherine?”

“A pleasure to meet you. Rochelle, is it?”

“That’s right,” I say, “but please, just call me Chel.”

I help her to her feet, and we wade through

To her office, which is as overgrown

As the rest of the gardens; crammed with vines.

In the furthest corner of her office

A single sarcophagus lays open;

Catherine was deemed important enough

To warrant her own private entombment.

“Have you seen anybody else?” I ask,

“All the other stasis beds are empty.”

She frowns. “What about the crew? Where are they?”

“I don’t know. You’re the first person I’ve seen.”

Catherine clears heaps of vines from her desk,

But her terminal is dark. “Where are we?”

“We’re in high orbit around a planet,

But I can’t get access to any logs.”

“Right,” she says, idly tugging errant leaves

From her dark hair, before tying it back.

“First, let’s find something to eat. I’m starving.

Then, we can see about finding the crew.”

“Here.” Catherine slides a section of wall

That looks like it should be solid bulkhead

Aside to reveal silver food packets

Laid out neatly, in perfect little rows.

“The walls are bursting with secrets,” she says.

“I installed this one myself, paranoid

The crew’s appetites might prove poisonous

After a few hundred years travelling.”

We choose a table beside the windows

Of a long concourse with analogue clocks

High on the walls. The clocks make me nervous.

I know they should tick, but they are all still.

The packets lack labels, and are all filled

With a thick brown substance that smells like bread,

And tastes wonderful, like salt and sugar

And sour fruit and ripe fruit all at once.

I am surprised at how hungry I am,

And Catherine laughs as she watches me,

Sucking at the silver packets to draw

Every drop of sustenance from within.

Her eyes have been heavily modified

And her irises glitter green, gold, blue.

If the rest of her has been engineered,

It is expert work: she wears no scarring.

“Give me your hand,” she says, her palm open,

And I reach across, glad at the gesture.

Her fingers are warm and they squeeze gently

At my wrist, our heartbeats close together.

A sharp sting. I snap my hand back. Blood runs

From the three small puncture marks in my skin.

The thorns in the heel of Catherine’s palm

Withdraw into her hand, and her eyes close.

“You should have asked,” I tell her, feeling stung

Literally and figuratively.

I have nothing with which to bind the wounds,

So I press my sleeve tightly against them.

“You should be dead,” says Catherine, frowning.

She opens her kaleidoscopic eyes.

“One small procedure to correct hearing,

But otherwise, as clean as a newborn.

“Why were you picked for this mission?” she asks.

“Your immune system is so primitive

You could be harbouring enough disease

To wipe out the crew and the colony.”

“Sigmund picked me personally,” I say.

“He does have unusual taste,” she says,

“But it might explain why we’re alone here.

We might have been put into quarantine.”

Beyond the windows, the new world is bright.

The crescent sunrise is waxing slowly,

And the Calypso’s dim interior

Glows as we turn to fully face the sun.

“Why would you have been quarantined?” I ask.

Catherine considers her reply, says,

“My immune system is state of the art.

Maybe I’m here as a sort of medic.”

What Catherine is saying does make sense,

But I still remain uncertain, idly

Finishing the last of a food packet

And pushing the empty silver aside.

“We need to speak to somebody,” I say,

Peeling back my bloody sleeve to reveal

Three dried puncture points; the bleeding has stopped,

“We can’t just sit around and theorise.”

“Well, we have two options,” says Catherine.

“Either we try and get through to the bridge,

Which I think is a few hours from here,

Or we try Sigmund’s office, which is close.”

I am not enthused by either option –

I am in no state for a long journey,

And nor do I want to disturb Sigmund.

His office feels like sacred ground to me.

Cramming food packets into our pockets,

We stride the gloomy hallways, our eyes fixed

On the moons newly revealed in the dark;

Four smaller crescents of light, like echoes.

Consider the boy whose name is Arthur Sigmund.

One day, when he is much, much older, he will fly

Far away from Earth, to go and build a new world.

Today, however, he is still only a child.

Sigmund lays in the long grasses behind his house,

Wriggling his toes beneath the blades, into the earth,

As if they are worms burrowing into the soil.

He knows that Mars was once dust, but is now alive

With worms that wriggle a lot like his toes wriggle.

He wonders about his mother, who put them there:

The toes on each of his feet, and the worms on Mars.

Sigmund does not recall much about his mother.

His most vivid memory is of fat pink worms

Writhing around his and her fingers, while she sang

Soft songs, kneading at the earth and feeding her worms

Into that loose soil – letting them feast and mingle.

She left before his fourth birthday; returned to Mars,

And though Arthur knows that Mars is very distant,

He feels as if he is living in its shadow.

Everyone knows how important his mother is,

And sometimes they treat Arthur as if he is her,

As if he is destined for some kind of greatness.

Arthur prefers his father, who is a farmer.

His father’s hands are coarse, and he knows about things

Like the dispositions of cows and hens and sheep,

And the passing of seasons, and good years, and bad.

Arthur’s father lives in the shadow of Mars, too.

The grasses swish in the breeze, concealing the boy;

Arthur is trying to hide from the housekeeper,

Who will soon discover that he has broken in

To his mother’s study, and stolen some supplies.

Beside him in the grass are pencils, and paper,

And an ornate pair of engraved gold compasses.

Rolling on to his stomach, Arthur starts drawing.

His scribbles take the shape of rockets and space ships,

And with the spike of the compasses, he pierces

Each thin sheet through, so they fly in a field of stars.

Dissatisfied, he takes a fresh sheet of paper

And uses the compasses to draw a circle.

Pencil poised, he pauses; the circle is perfect.

Rolling on to his back, the boy holds the paper

Up to the sky, considering the shape of it.

The circle is a hollow that could be something.

It is the outline of an idea, he thinks.

A wheel without spokes – a planet without people.

Behold the boy who bears the name Arthur Sigmund.

The boy has sailed alone into the Pacific

In a yacht stolen from one of his mother’s friends.

He has removed all of the yacht’s electronics

And is relying on a compass and the stars,

Because it is stars that the boy is searching for.

Arthur is starting to find the cities stifling;

He has a stiffness in his neck from looking up

And searching the gaps between the buildings for sky.

There is never enough sky to satisfy him.

Even out here, alone and exposed to the sky,

He wishes he could dive upwards into the stars.

The boy’s lonely journey has taken him through storms,

Through lashing rain and strong winds and towering waves,

In a yacht designed for a crew of at least six.

Sometimes he manages to catch snatches of sleep.

When he dreams he dreams of reaching up to the sky

And plucking stars as if they are pieces of fruit.

In those dreams he cups the stars between his worn hands

And watches the light leaking between his fingers.

A week into his voyage, the winds stop blowing;

The ocean stills; the boy falls into a deep sleep.

When he wakes, there are stars above and below him;

The likeness of the sky reflected perfectly

In the still waters, so that he is surrounded,

And at last the boy knows that he is satisfied.

When the winds pick up again, he starts to head home,

But instead finds himself drifting slowly southward.

The boy only has a few more days of food left,

And those days pass quickly, until he is starving.

On the third day without food, the currents take him

To the ocean at the centre of the ocean,

Where there are endless plastic packets and bottles.

Fishing is fruitless because everything is dead.

The boy lays back on the deck of his yacht and waits,

Listening to the thumping of plastic bottles.

To pass the time he recites the brands of the drinks

Those bottles once contained; remembers their theme tunes.

Through his delirium, he hears an insect hum

And opens his eyes to see a lone clean-up drone

Hovering overhead; the boy has been spotted.

The trash ship arrives, surrounded by humming drones,

And the boy is hauled roughly on board by a pair.

The crew promise to return Arthur to dry land

In a week, once they have filled their clean-up quota,

And during that week the boy learns just how futile

The clean-up effort is: there is just too much trash.

Arthur thinks a lot about the oceans on Mars.

He wonders if they are covered in bottles too,

Or if they are clean, and clear, and filled with fishes.

It seems suddenly vital to him to find out;

To sail all the way to Mars and see for himself.

Admire the young man who is named Arthur Sigmund.

The quickest journey to Mars takes about six months,

And most prefer to spend it in a numb stasis,

Vegetating in one of the shuttle’s gardens.

Sometimes Arthur visits them, watches their eyes twitch.

It is a crude kind of stasis – a waste of life;

Their minds switched to stand-by while their bodies decay.

Arthur has decided to spend the months reading,

And though the shuttle’s archives are almost endless,

He prefers the paperbacks in the library;

Well-thumbed relics mostly read by the elderly.

His university has funded this voyage;

An education in geoengineering;

But there is little on the subject to be found.

Instead, he has become absorbed in the classics:

The great epics – the Odyssey and Iliad.

There are four different translations of the former

To be found on board, and he is comparing them,

Making charts to plot different interpretations

That resemble stellar maps; all curves between points.

The first voyages to survey Mars took decades,

Arthur knows, and those people were true pioneers,

The red planet was still a real red wilderness

And their struggle was a true Homeric struggle.

None of them wasted away in a crude stasis,

Forced to choose between boredom or a long coma.

As the long voyage proceeds, Arthur grows restless.

He is excited to set foot on Martian soil,