Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Fox Chapel Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

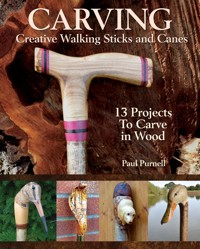

Put your wood carving skills to practical use! This must-have book features 13 projects with step-by-step instructions and photography for creative and elegant walking sticks. Including projects for beginner, intermediate, and advanced wood carvers, painting and finishing instructions are provided, as well as helpful information on types of wood used for walking stick shanks, methods for joining a head to a shank, and more. From a simple lyre-shaped thumb stick and a gent's walking stick to derby sticks with the head of a fox, eagle, Labrador retriever, black swan, and other animals, you'll enjoy putting your carving skills to the test by creating these beautifully useful walking sticks and canes. Author Paul Purnell is a self-taught wood carver for 15 years who specializes in birds, animals, and other wildlife. His carving style includes a mixture of tools, and he has carved projects for The Guild of Master Craftsman's Wood Carving and Woodworking Crafts magazines.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 273

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

© 2020 by Paul Purnell and Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc.,

903 Square Street, Mount Joy, PA 17552.

Carving Creative Walking Sticks and Canes is an original work, first published in 2020 by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc. The patterns contained herein are copyrighted by the author. Readers may make copies of these patterns for personal use. The patterns themselves, however, are not to be duplicated for resale or distribution under any circumstances. Any such copying is a violation of copyright law.

For a printable PDF of the patterns used in this book, please contact Fox Chapel Publishing at [email protected], quoting the ISBN and title of this book, as well as the pattern or patterns required.

Print ISBN 978-1-4971-0011-4eISBN 97-1-6076-5711-8

Library of Congress Control Number:2019945988

To learn more about the other great books from Fox Chapel Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free 800-457-9112 or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

We are always looking for talented authors. To submit an idea, please send a brief inquiry to [email protected].

Table of Contents

A BRIEF HISTORY

CHAPTER 1: TOOLS

CHAPTER 2: SELECTION, STORAGE & SEASONING OF WOOD

CHAPTER 3: STRAIGHTENING

CHAPTER 4: JOINING A HEAD TO A SHANK

PROJECTS

Multi-Wood, Lyre-Shaped Thumb Stick

Barley Twist Thumb Stick

Lady’s Half-Crook Walking Stick

Gentleman’s Dress Stick

English Cocker Spaniel Head Walking Stick

Black Swan Derby Walking Stick

Fox Head Walking Stick

Golden Eagle Derby Walking Stick

Common Pipistrelle Bat Walking Stick

Eurasian Woodcock Walking Stick

One-Piece Northern Shoveler Hen Walking Stick

Yellow Labrador & Mallard Walking Stick

Mantling Barn Owl Walking Stick

APPENDIX

PATTERNS

PHOTO CREDITS

MESSAGE FROM THE AUTHOR

A Brief History

Walking sticks have been used since the dawn of time as walking supports, weapons of offense and defense, badges of honor, status symbols, and even tippling sticks, where a flask of alcohol was concealed within the stick. Shepherds of Britain were probably the first to adapt a stick with a crook for a specific purpose relating to their work.

Many famous historical figures have been collectors of sticks or canes. Dating back to 1358 BC, Tutankhamen had approximately 130 elaborately carved sticks (some with gold adornments) in his tomb to assist his travels in the afterlife. Other famous names include Henry VIII, Winston Churchill, Queen Victoria, Napoleon Bonaparte, and the first President of the United States, George Washington.

In the 1600s walking sticks became a fashion accessory, and their elaborate designs were an indication of wealth and social standing. At this time the shafts were made from reeds, rattan, bamboo, and cane. Hence, the term “canes” was born.

However, this may not be the true origin of the word cane. During the time of the Romans, savage packs of wild dogs roamed the cities and towns, scavenging for food. For protection, people carried a cudgel made of wood with spikes inserted in one end. The word canis was the Latin word for dog, and the plural of canis is canes. Today, the terminology of a walking stick or a cane is interchangeable.

Although in the United Kingdom a cane is still seen as a fairly short shank without a curved handle, the opposite is true in the United States. In the UK, traditional sticks are deemed to be functional, while the fancy sticks are for show or as collectors’ items, and the original term used for making a traditional crook with a horn or wood handle is “stick dressing.”

Over time, conventions have developed as to the size and shape of the traditional sticks when entering competitions, whereas sticks with more elaborate heads depicting animals, ducks, etc., have few restrictions other than the stick and head needing to look balanced. The range of decoration of these sticks is a testament to the artistic talent and ingenuity of their makers.

Paul Purnell

CHAPTER1

Tools

Some carving traditionalists will say that only carving with hand tools is “real” carving and using any sort of power tools is not acceptable. Some will say that wood should never be painted. Everyone has an opinion. However, with the possible exception of when running a business, I believe that carving should be enjoyable, and any advice on tools, materials, and techniques should be helpful but not prescriptive.

You may try one of the many styles of carving, from the smallest netsuke through to chainsaw carving of a tree trunk. You will find what aspects of carving you enjoy and those that frustrate. After a few years of practice, you will develop your own individual style and discover what tools and materials you prefer and the techniques that suit you.

My style is a combination of power and hand tools, and I hope that the following information that I have discovered during my years of making walking sticks will help.

Band Saw

It was only after many years of carving that I treated myself to a band saw. If I could do it all over again, this would be first on my list of purchases. It is only when you have a band saw that you realize how much time is wasted when struggling to cut a blank with a handsaw, coping saw, or jigsaw.

You do not need a massive financial outlay to acquire a reasonable band saw. A small benchtop saw with an 8"–10" (20–25cm) throat is more than adequate for most woodcarving projects. The first thing to do when buying a band saw at the cheaper end of the market is to throw away the blade that it comes with, as it is likely to be of poor quality. The wobbly lines such a blade will make will make you wonder why you bothered buying the band saw. Buy the best blade you can afford, even for a small hobby-rated machine.

The second most important thing to do is to learn how to set up the blade correctly, as without this you will have difficulty making straight cuts, no matter the quality of the blade. Check the blade manufacturer's website for instructions on setting up the blade properly. The blade width will depend on your projects. A ¼" (6mm) blade will cut a tighter radius; however, the ½" (13mm) blade will cater to most of your needs when making walking sticks.

One of the huge benefits of a band saw is the ability to cut the blank in two planes. You must start with a block that has 90-degree angles. The process for cutting out a hare head for a walking stick is provided on the following page.

A ½" (13mm) blade will accommodate most of your cutting needs when making walking sticks.

With a band saw, you can cut a blank in two planes.

Rotary Tool

A rotary machine is needed for power carving, and a flexi-shaft is an important addition, as it removes the weight and awkwardness of having to hold onto the machine. There are many makes of small handheld, hobby-rated tools. The type you choose depends on what you are carving and for what length of time the rotary tool will be operating.

I wasted time and money on buying different makes of the smaller type of rotary tools, as most burned out within a year. Then I purchased a Foredom® flexi-shaft with a hand controller. What a difference! The quality, reliability, and torque are impressive. The machine will deal with anything you throw at it, and with its ability to take a ¼" shank bit, roughing out is made easy. There are many different Foredom machines available in the US, but the choice is limited in the UK.

The general-purpose handpieces (see photo on page) comes with three collets for shank sizes: 3/32", ⅛", and ¼". Quick-change handpieces shown below are available but only for the 3/32" shank. Having a couple of handpieces each fitted with your favorite bit will reduce the need for frequent changes of collet.

Foredom rotary tools are available with either hand controls (top) or foot controls (bottom).

CUTTING OUT A HEAD

1 Draw both the side and plan views on the wood block.

2 Use the band saw to cut one view. In this case, it is the plan view.

3 Secure the cut pieces back to the block with masking tape.

4 Cut out the side view. After removing the tape, all the cut pieces will fall away and you will be left with a blank that will reduce the amount of roughing out required.

Some carvers will have two or more machines to cover every eventuality. Foredom makes hangers (above right) in different styles and fixing brackets to cater for this.

The general-purpose handpiece accommodates 3/32", ⅛", and ¼" shank sizes.

Two ends of the spectrum: compare this 1" by 1" (25 x 25mm) carbide-point bit (left) with this 1/64" (0.5mm) small dental carbide cutter (right).

Quick-change handpieces are available only for 3/32" shanks.

Micro-motors have smaller handpieces that are less tiring and useful for curving strokes with detailing stones.

A Foredom hanger is ideal for carvers using more than one rotary tool.

If you intend to carve fine detail, a micro-motor (above center) is an invaluable addition to your main flexi-drive machine. While it does not have the torque of the Foredom machines, it has a smaller and more comfortable handpiece. This is less tiring on your hand and helps with the wrist movement required for curving the strokes when using the detailing stones.

When carving with a power tool, ensure that your sleeves are tucked out of reach of the bits, especially the carbide points. They love to snag on clothing, which could result in motor problems if you are holding the machine, or they will shear the inner cable of a flexi-shaft—a design feature to protect the motor.

Bits & Burrs

There is a bewildering quantity of burrs, bits, and buffers for a rotary machine. The photo above shows two ends of the spectrum of choice: a carbide-point bit at 1" by 1" (25 x 25mm) with a ¼" shank and the smallest dental carbide cutter of 1/64" (0.5mm).

Fortunately, Saburrtooth® has every base covered with its extensive range of bits with razor-sharp, carbide cutting teeth in extra coarse (orange), coarse (green), and fine (yellow) for five shank sizes: ¼", ⅛", 3/32", 6mm, and 3mm. (Other brands, such as Foredom and Kutzal®, also use color to distinguish courseness.)

The coarse bits (green) with the ¼" (6mm) shank are aggressive and extremely efficient at removing material during the roughing out stage. The ¼" (6mm) bits with fine cutting teeth (yellow) will effortlessly remove the marks left by the coarse bits and leave the wood ready for sanding.

With such a massive selection to choose from, where do you start? This will depend on your style of carving. There are some bits that you may use occasionally for a specific task, but there will always be a few personal favorites that you reach for most of the time. For carving the projects in this book, this is a selection of the carbide-point bits that I used. The choice is yours, but if you can, buy a couple of quality carbide-point bits, such as Saburrtooth, as they will last a lifetime.

For even faster removal of wood, Saburrtooth has buzzouts (left) and donut wheels (right), but they need to be fitted to a separate angle-head grinding unit.

Diamond-coated bits are ideal for finer work and detailing.

A word of warning: when I say the ¼" (6mm) carbide-point bits are aggressive, I mean aggressive, and they love to run across your hands and fingers, leaving an attractive pattern! Naturally, with all the other health and safety advice, gloves would be considered essential when using these bits. However, if like me, you cannot carve with gloves, ensure you have a well-stocked tin of bandages handy in the workshop!

Carbide cutters will leave a smoother finish than the coarse carbide-point bits. However, these can dull fairly quickly compared to the carbide points.

Bits for finer work and detailing come coated with diamond, sapphires (which are slightly coarser than diamond), and ruby. Ruby is supposedly the coarsest of the three but is one of my favorite detailers.

Some small steel cutters are also available, and the ball bits can be useful for faster removal of material in the likes of eye sockets.

Very fine texturing (e.g., texturing of bird feathers and animal hair) can be achieved using tiny diamond discs, or what are commonly referred to as stones, stone burrs, or Arkansas stones. They come in different colors, representing assorted grits: red/ pink are generally the coarsest, green is medium, and white is medium to fine. The white are normally natural Arkansas stone.

Ceramcut stones are colored blue and, in my opinion, the best. They have ceramic pieces bonded to the other materials they are made from, resulting in their holding a crisper edge and having a longer life.

Storage of Bits & Burrs

Storage becomes an issue once you have built up a collection of accessories. There are carousels from Foredom. A cheaper option is to make your own from scraps of wood or use a magnetic strip, which I have found does a brilliant job of stopping bits from rolling off the work surface into a pile of sawdust, never to see the light of day again!

Diamond cutoff discs are available for very fine texturing, but I find I don’t use them often.

Ceramcut stones have a crisper edge and a longer life, and are in my opinion simply the best.

Carbide cutters dull quicker than carbide points, but they leave a smoother finish.

Ruby-coated bits are not quite as fine as sapphire- or diamond-coated ones.

Whether you buy a carousel or create your own type of container, proper storage of bits and burrs will save you and your tools in the long run.

Sanding

Saburrtooth also has sanding covered with the range of ½" and 1" (13 and 25mm) cushioned mandrels, with sleeves in extra-coarse, coarse, and fine.

Additional sanding products include: small and large sleeves coated with aluminum oxide grit; cushioned drums that need cloth-backed sandpaper to be fitted; and split mandrels that also need cloth-backed sandpaper. There are a few ways of wrapping the sandpaper around the split mandrels. The single wrap of abrasive is my favorite for detailed work such as feathering. Radial bristle discs are another alternative.

Sanding by hand will be required for all projects. Cheap abrasives will not last; cloth-backed sandpaper is essential for the cushioned-drum sanders and is ideal for general sanding by hand. For any hard-to-reach areas, apply some superglue to the backing to stiffen the abrasive. Abranet® sanding sheets and strips are made from a material that contains thousands of small holes. It will outperform and outlast other abrasive sheets, so these, in my opinion, cannot be beaten when sanding by hand.

Carving Knives

Carving knives are one of my favorite carving tools to use. As long as they are kept razor sharp at all times, they will be an asset to your carving equipment. Once again, there are many knives to choose from and it will depend on your intended project. There are specialist knives for chip-carving, curved blades (for carving a bowl), and many different shapes of roughing and detailing knives in between. Flexcut® knives are supplied already sharpened, and this trio will deal with most tasks.

Each of these carving knives is specifically intended for (from left to right): detailing, cutting, and roughing.

Pyrograph

A pyrograph unit is not an essential piece of equipment even if you decide to feather and detail birds. The Ceramcut stones will do this adequately. However, the advantage of using a pyrograph is that it will give crisper lines when laying down feather barbs of the primaries and secondaries and defining the feather shaft. Some carvers will pyrograph all feathers of their carving, which requires plenty of patience!

In addition to the detailing work, a pyrograph unit is handy for cleaning up edges, undercutting feathers, and reaching into difficult places to burn away stubborn wood fibers. It is not essential for pyrographed feathers to be painted over. By using different heat settings and pressure, some excellent designs can be created that need only be finished with oil or varnish.

Saburrtooth sanding sleeves are incredibly efficient and will last a long time.

These aluminium oxide sleeves are another sanding option, and, being smaller, they are ideal for tighter spaces.

Radial bristles are useful sanders for finishing a piece and removing any fuzzy areas. Normally two or three discs are added to a mandrel.

Cushioned-drum sanders come in various sizes and are used with cloth-backed abrasives.

Split-mandrel sanders can have sandpaper attached as a roll or just one wrap. These are great for tight spaces and are my favorite sanders for detailed work.

Abradnet is a very efficient sanding cloth and, due to its design, does not clog. This is perfect if you are removing a surface that has previously been oiled.

Pyrography Tips

Rounded Skew

A good general purpose tip used for texturing fur and hair. Ideal for defining the quill of a feather, its edges, and the barbs on all stiff flight feathers (i.e., primary, secondary, and tail feathers). Will define the lamellae of a duck's beak.

Flattened Rounded Tip

Can be used for heavy texturing of fur and hair. Useful for undercutting feathers.

Round medium writing tip.

Useful for heavy texturing and general burnishing.

Traditional Pointed Skew

Same as the rounded skew but will enable access into tight corners.

Large skew

Has a slightly rounded edge and can be used for shading and also heavy texturing and flattening of the wood on either side of a feather quill.

Ball Tip

On a light heat setting, can be used to burnish work ready for painting, and will get rid of the fuzziness often associated with lime/basswood after texturing. Gives an even burn and can also be used to write with.

Scale-Making Tip

The ones shown here are “realistic keeled snake scale tips” especially used for rattlesnakes and others where the scales are keeled. Various shapes and sizes of scale tips include ones for fish.

Round Medium Writing Tip

Useful for heavy texturing and general burnishing.

More than 900 tips are available for this Razertip pyrograph's interchangeable-tip pen.

Some pyrograph units have handpieces with fixed tips. In my opinion, this is limiting and costly. Razertip supplies a unit with handpieces that can take interchangeable tips. And there are more than 900 tips to choose from! There are special designs for creating scales of different species of snake, and creating the outline for small feathers. The two sharp tips shown at the bottom are the ones I use for the detailing in these projects. Wire is available for making your own tips if you wish.

Finishing

How you finish your projects also comes from personal experience. Experiment with the range of finishing oils and varnishes and you will find a product that suits you. Some carvers prefer a high gloss on a walking stick with a natural wood head and may use a yacht varnish. Others prefer a matte finish. If a stick is intended for hiking or game shooting, I prefer to finish with several coats of oil; this will soak into the head and shank, giving more protection. Additional coatings of oil can be applied over the original whenever needed; however, varnishes can fade and chip, and the only option is to strip away the original layers and re-varnish.

If the finished head is to be painted, your options will depend on whether you paint with oil or acrylic. I use acrylic exclusively. In this case, the wood can be sealed with a sanding sealer, painted, and then sealed with a finishing oil or polyester-based varnish.

Alternatively, the head can be sealed with a finishing oil, painted with acrylics, then be sealed with a final couple of coats of oil. Naturally, there are many personal opinions as to whether water-based acrylic paint can be finished with an oil-based product. Like everything when it comes to carving, experiment and find what works for you.

There are a couple of projects in this book that use this later method of finishing. Two things are important: firstly, test your intended process on a scrap of wood from your project. Secondly, if applying oil under or over acrylic paints, let the different mediums dry thoroughly for a week before applying the next.

HEALTH & SAFETY FOR WOODWORKERS

Most health and safety considerations in the workshop are common sense. However, following are a few reminders to ensure that your woodworking remains safe, enjoyable, and risk free.

• Wearing eye protection is one of the most important things when working with power tools, especially band saws, table saws, and routers. Sometimes bits can become loose from the rotary tool or they can break apart into small pieces if defective. You can guarantee that if this happens, they will aim straight for your eyes.

• Make sure you protect your ears when using noisy machines.

• Use a dust extractor/filtration system when using power tools.

• A good-quality dust mask is advisable. (The disposable painter and decorator masks are rarely good enough.) Firstly, it prevents dust particles entering the lungs. Secondly, even some of the more common woods are toxic to health, causing anything from a rash, headache, and eye problems through to cardiac issues. It could be argued that any wood could be toxic to a specific individual, but some are toxic to every wood worker. Always research the toxicity of the wood you are using if you are unsure.

• For a power or knife carver, a decent protective glove will prevent many injuries. A ¼" (6mm) coarse carbide-point bit loves to run across your hand, leaving marks like a pincushion. A sharp carving knife will give you a scar to remember. The standard of gloves is improving every year. They are lightweight with cut-resistant fibers incorporated into the design. Beware of cheap gloves, as they won’t even save you from a thorn prick in the garden. And a pair of leather gloves will minimize injuries, but these are often too thick and stiff. They prevent you from holding the workpiece properly and feeling your work.

• Appropriate clothing should be worn at all times. Baggy sleeves will get tangled with a carbide-point bit if it comes within breathing distance. If you are using a flexi-shaft machine, it will cost you the price of a new inner cable, as they are designed with a shearing-point for such circumstances. Shirttails or loose jackets can become snagged in a band saw or table saw and result in serious injury. A leather apron, or other suitably reinforced material, is a must if you use a knife to carve your project while holding it in your hand.

• Remove any jewelry dangling from your neck or wrists.

• I have already mentioned that woodcarving should be fun, and I wouldn’t want to go back on that sentiment; however, alcohol should be drunk only when you are admiring your finished article, not while carving it. The same goes for medication, so be aware of any side effects of the medication you are taking. Many types will make you drowsy and impair judgment.

Possible Reactions to Woods

Wood

Class (Irritant or Sensitizer)

Reaction Type

Potency

Source

Incidence

Alder

Irritant*

Respiratory, eye and skin

No info †

Dust

No info

Ash

Irritant

Respiratory

No info

Dust

No info

Avodire

Irritant

Respiratory, eye and skin

No info

Dust

No info

Baldcypress

Sensitizer**

Respiratory

Small

Dust

Rare

Beech

Sensitizer

Respiratory

Great

Dust

Rare

Birch

Sensitizer

Respiratory, nausea

Great

Dust

Rare

Black locust

Irritant

Nausea

Great

Dust

Rare

Bubinga

Irritant

Eye and skin

No info

Dust

No info

Red cedar, Eastern

Irritant

Respiratory, eye and skin

No info

Dust

Common

Red cedar, Western

Sensitizer

Respiratory

Great

Dust, leaves & bark

Common

Cocobolo

Irritant

Respiratory, eye and skin

Great

Dust & wood

Common

Ebony

Irritant & sensitizer

Respiratory, eye and skin

Great

Dust & wood

Common

Elm

Irritant

Eye and skin

Small

Dust

Rare

Goncalo alves

Sensitizer

Eye and skin

Small

Dust & wood

Rare

Greenheart

Sensitizer

Respiratory, eye and skin

Extreme

Dust & wood

Common

Ipe

Irritant

Respiratory, eye and skin

No info

No info

No info

Mahogany

Irritant

Respiratory, eye and skin

Small

Dust

Rare

Mapl (usually only spalted)

Sensitizer

Respiratory

Great

Dust

Rare

Oak, red

Irritant

Nasal

Great

Dust

Rare

Padauk

Irritant

Respiratory, eye, skin, and nausea

Extreme

Dust & wood

Common

Purpleheart

Sensitizer

Eye and skin, nausea

Small

Dust & wood

Rare

Rosewood

Irritant & sensitizer

Respiratory, eye and skin

Extreme

Dust & wood

Common

Sassafras

Sensitizer

Respiratory, nausea, and nasal cancer

Small

Dust & wood

Rare

Teak

Sensitizer

Eye and skin

Extreme

Dust

Common

Walnut, black

Sensitizer

Eye and skin

Great

Leaves & bark

Common

Willow

Sensitizer

Nasal cancer

Great

Dust

Common

* An irritant causes an almost immediate reaction each time the wood is used. ** A sensitizer does not necessarily irritate, but it makes a person more likely to be strongly affected by a wood classed as an irritant. If you are exposed to an irritant after being exposed to a sensitizer, you are more likely to have a more serious reaction to the irritant. † No info indicates that the information for this wood is still being developed.

• Ideally, the piece you are working on should be securely clamped in a workbench vice or one of the many carving holders available. This leaves both hands free. However, there are times when this is not possible, and most of the projects in this book cannot be carved using a carving clamp.

• Disconnect the power source before changing blades of band saws and table saws.

• Use drill bits that are sharp. Exerting undue pressure may cause the bit to wander and also put the user at risk of slipping.

• Keep your carving knife and gouges sharp. A sharp knife will do more damage than a blunt one if it slips, but a sharp knife reduces the chance of slipping. I carve with a thick carpet beneath my carving station. This minimizes damage to the blades if dropped. Also, it is natural instinct to try to catch a falling knife/gouge, but that can result in serious injury. With a rug or carpet beneath, you don’t have to worry as much when dropping a tool.

• When using a table saw, always stand to one side to minimize injury should there be any kickback.

CHAPTER2

Selection, Storage & Seasoning of Wood

Choice of Wood for the Heads

The genus tilia includes more than thirty species and hybrids of what is more commonly known as lime, linden, or basswood. If the head of the walking stick you are carving is to be detailed and/or painted, this is likely to be your first choice of wood along with tupelo (nyssa). Both of these woods are a plain creamy color but fine-grained and good at holding detail, as long as you purchase quality material free of defects. The downside of basswood is that using power tools can leave the wood with fuzz that is sometimes difficult to completely remove. Tupelo is a better option when using power. (Note to UK readers: this wood is difficult to source in the UK.) Both woods can be carved easily with a carving knife.

Thumb stick with brass collar.

Cobra using spalting pattern of a piece of beech for effect.

Skull.

Unicorn (commission for a psychic medium).

Caricature of a cowboy’s head.

Natural wood carving of a cocker spaniel and duck.

If the head is not being painted nor detailed, you can choose any wood you have access to. Often this will depend on the country where you live, but any decent merchant should have a wide variety of wood species available. Throughout the world there are some exotic woods with stunning colors and grain detail. One of the joys of wood carving is that every piece of wood is different, and even a plain piece of basswood might hold a surprise if it has been attacked by a fungal growth, leaving patterns that can rival some of the exotics.

Selection of Wood for the Shank

There is nothing more satisfying than finding and cutting a shank to make your own walking stick. However, all land and every tree on it belongs to someone; you need the landowner’s permission before cutting and removing any wood. In the UK, this also applies to common land where it is a criminal offense. Most landowners are approachable and amenable if you explain your purpose.

Almost any tree species is suitable for a walking stick shank. It is the country where you live that will often dictate which is available to you. The species you choose will also depend on your intentions: Will it be a stand-alone stick with no attachments? Will you need a straight or crooked shank? Will it have a head joined? Should the wood/bark be carved and/or stained/painted? Do you need a tall/short stick that is heavyweight/light? Will the stick be used as a walking aide, where strength is an issue?

Often, the wood will have several outer layers and can reveal some stunning patterns if the outer bark is sanded off. For straight sticks, look to the species that coppice well (e.g., hazel, ash, aspen, sweet chestnut.) Even within different species, there will be variations as to how the wood will behave. But this is all part of the enjoyment!

The most common species used in the UK are detailed in the table on page.

The length that you cut your stick will depend on whom it is for and the style preferred. If making a stick for someone else and you don’t know his or her height, a rough guide for a hiking stick for a person 6' (1.8m) tall is 55" (1.4m). For a short walking stick, aim for 36" (0.9m). However, if you intend to make more than the one stick, cut any that you find, long or short, as they can all be put to good use when seasoned.

Most bends in wood can be straightened with heat treatment, but an elbow joint like the one shown here, commonly known as a “dogleg,” can be stubborn and often not worth the time and effort.

The diameter is also an individual preference. If in doubt, a standard diameter of a finished stick is around 1"–1 3/16" (25–30mm) at the top, tapering to a tip diameter of ⅝"–⅗" (16–19mm). Don’t ignore thicker shanks, as they can be used for carving wildlife and other features along their length.

Keep in mind when cutting that the shank will lose approximately 25 percent of its diameter during seasoning.

Common Species Used for Shanks in the UK

Hazel (Corylus avellana)

Hazel is very common in the UK and is the shank of choice for many handmade walking sticks.

It straightens easily and has attractive bark that ranges in color from silver to red brown with the many shades in between.

If you intend to attach a separate head to the shank, hazel is the most popular choice.

Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa)

Blackthorn has a rich cherry-red color. It often grows in dense clumps and has vicious thorns (and it is inevitable that the shank you are after will be in themiddleof such a patch). A pair of gloves and eye protection are advisable.

Blackthorn is on the heavy side for a walking stick shank.

Hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna)

Another prickly character. A dense wood, like blackthorn, that makes an attractive shank with the bark left on.

Can be difficult to find a straight section long enough for a walking stick.

Ash (Fraxinus excelsior)

A tough wood that absorbs shocks (which is why it is used for cricket bats and the handles of many woodworking tools).

Identifiable in winter by its black, velvety leaf buds. Bark is a silver color.

Holly (Ilex aquifolium)

The bark can be fickle, in that it sometimes peels away easily when straightening. However, the bark is often stripped, as the wood can have a well-figured grain.