9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

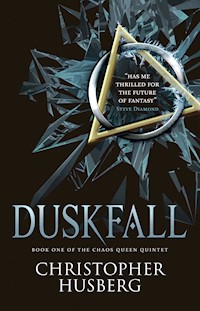

The start of a rich and gripping fantasy series of dark magic, oppression and rebellion perfect for fans of Brandon Sanderson's Mistborn and Robert Jordan's The Wheel of Time.Stuck with arrows and close to death, a man is pulled from the icy waters of the Gulf of Nahl. As he is nursed back to health by a local fisherman, two things become very clear: he has no idea who he is, and he can kill a man with terrifying ease.The fisherman is a tiellan, a race which has long been oppressed and grown wary of humans. His daughter, Winter, is a seemingly quiet young woman, but behind her placid mask she has her demons. She is addicted to frostfire - a substance that both threatens to destroy her and simultaneously gives her phenomenal power.A young priestess, Cinzia, hears the troubling news of an uprising in her native city of Navone. Absconding from the cloistered life that she has kept for the last seven years, she knows she must make the long journey home. The flames of rebellion threatening her church and all that she believes in are bad enough, but far worse is the knowledge that the heretic who sparked the fire is her own sister.These three characters may have set out on different paths, but fate will bring them together on one thrilling and perilous adventure.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Christopher Husberg

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Part I: Shadows

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Part II: Everything that Rises

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

Part III: Kill to Feel

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

Part IV: Daemons Even Daemons Fear

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Christopher Husberg and coming soon from Titan Books

Dark Immolation (June 2017)

DuskfallPrint edition ISBN: 9781783299157E-book edition ISBN: 9781783299164

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: June 201610 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2016 Christopher Husberg. All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

FOR RACHEL

PROLOGUE

170th year of the People’s Age, The Gulf of Nahl

BAHC STOOD AT THE bow of his fishing boat, clutching a small oil lamp. Its light pressed against the night, illuminating the large white snowflakes around him. In the distance the flakes were dimmer, floating through black sky and into blacker ocean, disappearing into calm, cold swells.

Bahc breathed in, licking salt from his lips. He loved the taste of the sea after a storm. He removed a glove and patted the rail of The Swordsmith’s Daughter, feeling the cold grain of the wood. Bahc had designed and built the boat himself, with the help of the other tiellans in Pranna, years ago. When times were different.

Behind him, the deck creaked.

“Just like that, eh?” Gord said.

Bahc looked over his shoulder. Gord also carried a lantern, and his huge frame—massive for a tiellan—cast a long shadow behind him. He wore coarse wool and rugged furs, and his long, thick beard was frosty with ice.

Bahc lifted his wide-brimmed hat up to get a better look at the water. “Aye,” he said. “Just like that.”

“Least it’s in our wake, now.”

“We’re lost, Gord. We’re not in the clear, yet.”

Gord leaned against the boat’s railing. His breath formed clouds of mist against the cold. “Figured. Now it’s just us waitin’ for the stars to show themselves again, eh?”

“Aye. We drift, for now, and hope we don’t end up somewhere we aren’t supposed to be.”

Bahc turned. He was about to go below decks to tell the rest of the crew, when something made him stop and turn back. He looked out at the blackness. Dark water, dark sky.

But not all dark.

In the distance, a bright blue light flickered on the water. Bahc’s gut clenched.

“Put out your lamp, Gord,” he murmured. He was already snuffing out his own.

“D’you think they saw us?” Gord asked, barely above a whisper.

“I don’t know,” Bahc said, grinding his teeth. “There’s some distance between us. Our lights aren’t bright. But the night is clearing up.”

“The wind’s at their backs,” Gord said.

It was true. If the vessel emitting the eerie blue light visible off the starboard bow had seen them and wanted to pursue, the wind would bring it straight to The Swordsmith’s Daughter.

“Then we’d best put it at ours,” Bahc said.

“On our way, then?” Gord was already moving to the mainmast.

“Aye. Straight away from them.” Bahc walked towards the cabin. “I’ll wake the others. We’ll need every hand.”

“Cap’n,” Gord said. Bahc looked over his shoulder. His crew didn’t use formalities much on his boat, on his own insistence. But when waters got rough, there was comfort in a chain of command.

“D’you hear that?” Gord’s head was cocked to the side.

Bahc heard nothing at first. But then there it was, soft as the falling snow. A small, rhythmic thud, in time with the water lapping against the boat.

He frowned, walked back to the bow and looked over the side. Something gently brushed against the hull. Bahc squinted in the dark.

It was a body.

Bahc cursed. “Prepare the winch. Try to bring him aboard. I’ll get the others.”

“You sure?” Gord asked. “Nobody can survive for more’n a few minutes in these waters. He don’t look too fresh.”

“Get him aboard,” Bahc said. “That’s an order.”

* * *

The body fell to the deck with a dull thump. Bahc stared at it, conscious of his crew doing the same. The paleness of the skin, practically blue in the darkness, meant the cold had probably already done its work. But, given the two long, thick arrow shafts jutting from the body, the cold seemed the least of this man’s worries.

Bahc saw that his daughter, Winter, was also staring at the corpse. He wished he hadn’t brought her. Twenty summers or not, he didn’t want her to see the lifeless form.

Not lifeless, Bahc realized. The body—the man—was shivering.

“Shit,” Gord muttered. “Is he…”

The man coughed violently, and vomited a stream of water onto the deck.

“Gord, take the helm,” Bahc said. “Get us out of here.” He turned to the body. The man. “Lian, help me get him below into the galley.”

“Papa, what are you doing?”

Bahc closed his eyes. Winter. She was involved now, there was no helping it. Bahc thought once again of the flickering blue light in the distance. He could dump the body and leave; this man was as good as dead, anyway.

Instead he opened his eyes, and reached down for the man’s legs. Lian, the youngest crew member, was already lifting the man’s arms.

His daughter had seen enough death. Today, at least, she would not see another.

“We’re going to save his life,” Bahc said.

* * *

After a few hours, the man’s color began to return. That was good. This wasn’t the most extreme case of cold Bahc had seen, but the arrow wounds were serious. Bahc, with Lian’s help, had removed the shafts and cleansed the wounds with fire; the acrid smell of burning flesh still lingered. They had warmed the man, removing their own clothing and huddling with him on the floor underneath a half-dozen thick wool blankets, near the furnace in the corner of the galley. Lian had objected at first—said he didn’t want to go skin to skin with a human—but it was the only way Bahc knew to warm someone this far gone. Decades of fishing in the Gulf of Nahl had taught Bahc the effects of such cold. Massaging limbs and hot water never worked. You had to warm their blood at the source. Had to warm their heart. Even after all that, Bahc wasn’t sure this man would make it.

Or themselves, for that matter. Bahc couldn’t stop thinking of what might be chasing them. The blue light in the distance. His crew had gotten them moving quickly, and Gord had checked in twice now to report. There was no sign of pursuit.

But still, Bahc worried. Mostly about Winter.

Bahc put his hand to the man’s chest. The man’s skin felt warmer than before. He touched his fingers. They were cool, but no longer ice-cold. Bahc pushed off the blankets and stood up.

“Get dressed,” he told Lian, reaching for his trousers. “We still have work to do.”

Lian nodded. Once they were dressed they lifted the man from the makeshift bed and placed him on the table that stood in the center of the galley.

Behind Bahc, the door opened.

“Think we’re clear, Cap’n,” Gord said.

Bahc relaxed. “You have a bearing?”

“Aye. We glimpsed the stars just for a moment, but Winter got a good look. Should be moving due south now, and dawn’ll confirm that.”

Bahc nodded, and looked back down at the man. His skin had gone from almost blue to pale white, which made it easier to see the cuts, bruises, and old scars that covered his body.

Gord remained at the doorway, staring at the man on the table.

“How’s he doin’, eh?”

“As well as he can be. His color is returning, but that doesn’t mean much, given his other injuries.” Bahc frowned. Gord still stood halfway in the doorway. “Get out and close the door, Gord. You’re letting the cold in.”

Bahc turned back to the table. Just as he was about to ask Lian to refill the bucket with more hot water, the man on the table twitched, and then the whole room was a whirlwind of movement.

It took a moment for him to realize what had happened. Bahc found he’d been spun round from the table to face the doorway again, and the jagged end of one of the broken arrow shafts was pressed into the skin of his neck, a strong arm immobilizing him. The man had moved so quickly. The metal pan that held the other shaft and arrowheads clattered to the floor.

No one moved. Bahc blinked. He could just see Lian’s shocked face out of the corner of his eye. Gord, still in the doorway, took a slow step forward, hand creeping to the dagger at his belt.

The arrow shaft pressed forcefully against Bahc’s throat.

“Don’t m-move,” the man rasped in a cracked whisper. Bahc felt the man’s hot breath in his ear. “Who are you?”

“We’re not going to hurt you,” Bahc said, trying to keep calm.

The man trembled. “I d-don’t… I don’t remember…” he rasped.

The door slammed shut behind Gord. There was no one near the door, at least not inside the room. Bahc wondered whether Winter had found her way down, and prayed she had not. Whatever was going on, he didn’t want her to have any part in it.

“What in Oblivion…” Gord grunted, looking at the door that had slammed behind him.

A bucket flew across the room, whizzing past Gord’s head and crashing into the wall. Bahc would have thought someone had thrown it, but it had come from the corner of the room where neither he nor Lian nor the man were standing.

Bahc felt the man’s grasp—and the pressure from the arrow shaft—slacken for the briefest moment. Then the room erupted into chaos.

Tin cups and wooden spoons streaked from wall to wall, propelled by nothing. The pliers Bahc had used to remove the arrow shafts flew upwards, embedding themselves nose-first in the ceiling. A box of fishhooks Bahc had set out earlier to clean shattered; Bahc shut his eyes as the hooks exploded in all directions. The table the man had been lying on shook violently, creaking against the bolts that held it to the floor.

Bahc looked around. Gord had dropped as soon as the bucket flew past. Lian lay on the floor on the other side of the table, not moving.

Bahc felt himself freed from the man’s grasp. He turned slowly. The man wobbled, his hands at his sides. He still clutched the arrow tightly in one fist. Bahc took a step away as he saw the man’s eyes roll back. Only the whites showed, shining in the lamplight. His face contorted in pain and confusion. Then he fell, his strangled shriek ringing in Bahc’s ears, and all movement stopped. Objects flying through midair dropped to the floor.

Bahc stood, breathing heavily. What he had just seen was impossible. Or at least it should be. But he had seen it once before. The day his daughter was born.

The night his wife died.

Gord rose to his feet slowly, muttering something about ghosts. Lian moaned softly. The stranger lay crumpled, chin resting on his chest, eyes closed. Peaceful, as if he’d fallen asleep.

“We tell no one,” Bahc whispered, looking around at the mess: utensils everywhere, hooks embedded in walls, containers overturned. “No one.”

Gord nodded, slowly. “What about Lian?”

“I’ll talk to him.” They couldn’t let this get out. It was too dangerous. No one—human or tiellan—would understand.

“What’re we going to do?” Gord asked, looking around the room nervously.

“Bind the man,” Bahc said, retrieving a few long scraps of leather that had been scattered on the floor in the chaos, and handing them to Gord. “And then…”

He trailed off as the stranger groaned.

Bahc sighed. He had made up his mind. “Then,” he said, “we take him back to Pranna.”

1

One year later, Pranna, northern Khale

AFTER SHE HAD BATHED and dressed, Winter slipped quietly out of the house into the bleak morning light. She wasn’t sure if her father was up yet, but Cantic tradition dictated that the bride should not have any contact with the men in her family, or the groom, until the ceremony.

“The bride,” Winter whispered to herself. Sometimes she just had to hear herself say a thing to believe it.

She tried again. “I’m getting married.” She had thought the idea might finally sink in on the day it happened, but apparently not. Marriage still seemed as foreign to her as air to a fish.

Winter looked back at her family’s small cottage, wondering if she shouldn’t find her father, anyway. They didn’t put much stock in religion, not anymore. But seeing him would be awkward, and provoke a conversation that she wasn’t sure she could face quite yet. She didn’t know how to tell him what was in her heart. She wasn’t sure she understood it herself.

Deep, slow breaths were the key. They always were.

She shivered in the crisp air and kept walking. It was cold, but not as cold as Pranna could be in the middle of the long winter. The sun hid behind a wall of gray clouds; the threat of snow loomed on the horizon.

Cantic tradition also stated that, the morning of the wedding, the bride was to have a Doting—to be given gifts by those closest to her. Since most tiellans had already left Pranna, that left precious few. One old king’s abdication and act of emancipation one hundred and seventy-one years ago had still not erased a millennium of slavery. Old prejudices ran deep. Tiellans were shorter than humans, with slender, pointed ears, larger eyes, and rarely grew hair on their bodies, except for the tops of their heads. Of course, after centuries of interbreeding there were exceptions, Gord being one of them with his unusually tall build and full beard.

Winter still did not understand how such minor differences caused such great conflict. But the results were clear enough: Gord and his brother Dent, Lian and his family, and Darrin and Eranda and their children were the only tiellans who remained in Pranna besides Winter and her father. The fact that so many had left weighed on Winter’s heart; tiellans were always reluctant to leave their homes.

“Not always,” Winter whispered to herself, glancing at the sea in the distance.

Her Doting was supposed to be at Darrin and Eranda’s home, but Winter stopped at the small intersection in the road ahead. To her right, not far down the dirt road, was Darrin and Eranda’s hut and the few friends she had in the world. To her left, the Big Hill ran down to the Gulf of Nahl. She saw the dock, and her father’s boat, far below. One path offered duty and those who loved her; the other offered freedom and the beautiful terror of uncertainty.

Winter paused, even though she already knew her choice. She allowed herself to imagine, briefly, leaving everything behind. She had never felt at home in Pranna. She didn’t know why. Even with her friends, sometimes even with her father, she never felt whole. A piece of her had always been missing, and she had never known what it was, or how to get it back.

She imagined herself at the helm of her own ship. A small crew to call her own. Perhaps a lover. Perhaps not.

And she imagined that life crashing down all around her. There wasn’t much room in the Sfaera for the tiellan race anymore, and even less room for a tiellan woman.

What makes you think you’d fit in any better on a ship, away from Pranna, than you do here? Winter shook her head. It was a useless daydream.

With a sigh that she could see in the cold air, Winter pulled her cloak more tightly around her and took the right-hand fork.

* * *

“Ready to give your life away to a human?” Lian asked her, when they finally found a moment alone during the Doting. Lian spoke with a leisurely, lilting drawl, like most tiellans. Winter did not, because of her father. “The language of captivity,” he called it.

Lian’s parents and Darrin and Eranda were momentarily distracted with talk of more tiellan persecution in the nearby city of Cineste when Lian had sat beside her, near the fire. Winter had been listening to the others talk. She loved these people, but did not know how to show it. More often than not, she found herself simply observing, as she did now. Even at her own Doting.

Turning to Lian, Winter couldn’t tell if he was being sarcastic or genuine. Probably both; he was smiling, but the expression didn’t reach his eyes.

“Knot is a good man,” Winter said, though the words felt worn from frequent use. “Humans aren’t all bad, you know.”

“Right. It’s just that you’re marrying one, is all.”

“I don’t trust humans, but that doesn’t mean I hate them. You’re much better at that than I am.”

Lian’s eyebrows rose. “But this one you trust?”

Winter didn’t say anything. Trust had always been a rare commodity for her. She suspected it was the same for every tiellan. Humans cheated you, betrayed you, and would take everything you owned if you let them. Some tiellans would do the same. If she was honest, Winter only trusted a few people: herself, and her father, certainly. Gord, Darrin and Eranda, and Lian, too. Knot… Knot was not yet close enough to count.

They sat in silence for a moment. The others’ chatter seemed distant in the background.

Winter knew what was coming. “Please don’t ask me again,” she pleaded. She wasn’t sure she could take it. Not today.

“Still haven’t given me a straight answer,” Lian said. “I’ll keep askin’ ’til you do.”

“The advantages are clear. Any tiellan who marries a human is better off, no matter who that human is.”

“Even if that particular human has no idea who he is or where he came from?”

Winter frowned. She hated this conversation for a reason. Part of her agreed with Lian; what she was doing was difficult to justify. And yet, if Knot could take her away from Pranna, Winter might have a chance to really live—not just waste away in a dying town. Even if Knot wasn’t the man she imagined, she could cope if it meant getting away. She was a tiellan, after all. She could endure, if she had to.

And, perhaps, if she left, she might find somewhere she belonged.

“D’you remember that time you nearly drowned?” Lian must have grown weary of her silence. “That summer, when we were young.”

Winter blinked at the question, but couldn’t stop her lips twitching into a grin, however slight. “Which one?” she asked.

Lian smirked. “I suppose nearly drowning was pretty common for us back then.” He looked into her eyes. “You know the time I mean.”

Winter did know. She had only been eight or nine, playing on the dock with an earring of her mother’s, taken from her father’s room without his knowledge. The earring had slipped through Winter’s fingers, between the boards of the dock, and into the water below.

Winter remembered not thinking about what she did next. She just did it. She jumped into the water and started searching for the earring. She remembered diving in, coming up for air, diving down again. There hadn’t been much daylight left, the water was murky, and Winter had hardly been able to see anything. Each time she went down her hands dug into the mud at the bottom, but came up with nothing. She didn’t know how long she surfaced and dived again, but she remembered the panicked constriction in her chest, and the tears mixing with seawater on her face.

The sun set, the water grew colder, but still she continued, even when her muscles began to cramp. Looking back, Winter couldn’t say what had come over her. In that moment, all she knew was the need to find the earring. There had been nothing else.

Lian finally found her, shivering and spluttering, about to dive once more. To this day, Lian swore it would have been her last dive. He jumped in just as she went down. He took hold of her, and pulled her to the surface.

Clutched in her hand had been her mother’s earring.

She looked at Lian. “Are you angling for another thank you?”

He laughed. “No. Just wanted you to remember. Sometimes you think you need a thing, you fixate on it, and you don’t know when to give up. But that’s the best thing you can do, sometimes—let a thing go. Just wish you knew when to do it.”

“Me too,” Winter whispered.

Then suddenly Lian reached out, brushing a strand of hair from her face.

Her hand snapped up, gripping his.

“Don’t.” Winter lowered their hands, his in hers, gently. Friendly affection was one thing, but this was her Doting, for Canta’s sake. And the touch reminded her of a time she wasn’t interested in revisiting.

“Sorry,” he mumbled, and seemed to mean it.

“So am I,” she said, but knew she didn’t.

* * *

The Doting went as well as Winter could have expected. The small cottage smelled of fresh bread and cinnamon, smells that reminded her of her mother. Silly, that anything should remind her of a woman she had never known, but it was true all the same.

The gifts Winter received were plain, but meaningful. A traditional tiellan siara of beautiful white wool, a small woodcarving of a man and woman standing close together, a black-stone necklace to bring out her dark eyes, and a swaddling cloth that made her cringe at the thought of having a child.

Then, too soon, a knock came at the door. Three Cantic disciples in red and white robes stood outside. The women—humans, all three—made Winter nervous. Humans always did, though she tried to hide it. Winter looked down at her dress, coarse brown wool that covered her from to wrists to ankles, and the grey siara she wore, a long loop of fabric wrapped in folds around her neck and shoulders. A stark contrast to the sleeker, form-fitting dresses and exposed necklines of the human women before her.

Winter felt a stab of disappointment that there were only three. Cantic tradition called for nine disciples of the Denomination to escort new brides to their Washing; nine to represent the original disciples of Canta. Winter wasn’t sure if there were only three because the town population had decreased so dramatically, or because she was tiellan and the disciples didn’t think she merited a full escort. Her disappointment surprised Winter. It was a detail she had never thought would mean much to her.

She felt a sudden surge of panic, a great weight locked away within her chest threatening to break free. This wasn’t what she wanted.

Then the feeling passed. She would do what was required.

Winter said her goodbyes to her friends, the last time she would see them as Danica Winter Cordier, daughter of Bahc the fisherman. Whether she wanted it or not, change was coming.

* * *

“Can it be? My little girl is really getting married?”

Winter smiled as her father walked into the Maiden’s Room. Fathers were the only males allowed in the area, and only right before the ceremony. Winter was alone; the three disciples had left to prepare the chapel.

Despite her misgivings, Winter adored how handsome her father looked. He wore his only formal suit: loose, faded gray trousers and dark-blue overcoat in the old fashion. So different than his normal furs and wool—his fisherman’s clothing.

“Hi, Papa.”

She felt his arms around her, his tanned, smooth cheek against hers.

They separated, and she let him look at her. Her raven-dark hair was tied with a bow behind her head, and the disciples had seen fit to place the black-stone necklace she had received around her neck, matching the deep blackness of her eyes.

Winter had changed into a red dress, the only article of clothing her father had kept of her mother’s. It was simple dyed wool, but the fabric was fine and cascaded over Winter’s thin frame elegantly. The sleeves reached her wrists and the fabric covered her neck, but this dress actually fit her, hugging her hips and chest tightly. It was technically within tiellan standards, but at the same time whispered subversion. Winter imagined her mother wearing it years ago, and the outrage it must have caused the tiellan elders and matriarchs. The thought made her smile.

She waited for her father to speak, wondering if he would. Her father was never much for words.

“Your eyes are your mother’s,” he finally managed. “Dark as the sea at midnight.”

She smiled, trying to keep the sadness from her face. “So you’ve told me, once or twice before.”

“She would be proud of you, Winter.”

Would she? From what her father had told her, her mother had always been an independent woman. Winter wasn’t sure her mother would approve of her daughter giving up so easily.

“I hope so.”

Her father sighed, and waved a hand. “Bah. Enough, Winter. I know you’re not happy about this. I know this isn’t what you wanted.”

Winter stared at her father. “You do?”

“Of course I know. You think I can’t tell when my daughter is trying to suffer in silence? You are just like your mother, that way. I know you have concerns. But Knot is a good man. He’s not the type of human that would… he’s a good man, Winter. He’ll take care of you. He’ll give you a life that I never could.”

What he said was true. Even someone like Knot, with so little, could give her so much. If they moved to the city, somewhere they could make a fresh start…

“What if I don’t want that life? What if the life I want is exactly the one you can give me? Or Lian? What if I want to make my own life, Father?”

“Goddess rising, you are so like her it’s amazing,” her father said.

Winter sat down. Even as she said the words, she knew it wasn’t possible. There was no making her own life. Knot was her only chance. She needed him.

“Here’s the thing,” her father said, taking her hands in his. “You’re marrying this man. There’s no stopping that. But you haven’t signed your life away. It is what you make of it. Knot may surprise us all and turn out a tyrant; if that’s the case, you have my permission to murder him in the night and escape to make a life of your own.”

Winter smiled, although the joke was uncomfortably close to a few situations she had heard of in the city.

“But I don’t think that will be the case,” her father continued. “I think he’ll want you to be happy, and I think he’ll want to help you do whatever you need to find that happiness. Don’t underestimate that bond, my dear. Marriage, done right, can be much more freeing than we give it credit for. I think the two of you need each other.”

Winter was about to ask what her father meant by that when a knock sounded on the door. “Holy Canta calls her maidservant,” a woman’s voice said. “Will she answer?”

The priestess was ready.

Winter glanced at her reflection in the small looking glass opposite her. The girl who gazed back at her was confident, calm. That girl could almost be happy. Could almost believe what her father was telling her.

“Winter,” Bahc said, “today is your day. Accept your own happiness.”

Winter cleared her throat. “She will answer,” she called, in response to the priestess’s summons. She turned and walked towards the door, pausing to kiss her father on the cheek.

“I love you, Papa,” she said. Then she opened the door, and walked into the chapel.

* * *

She did not flinch as the small dagger slit her palm.

“And do you, Danica Winter Cordier, covenant through blood and in the presence of Holy Canta that you will give yourself to Knot now and forever, through frost and fire, storm and calm, light and dark, dusk and dawn and throughout the turning of time?”

“I so covenant, by my blood,” Winter said. The priestess, a rotund woman in her middle years, looked approvingly down at her from a large square pedestal. She took Winter’s hand and placed it in Knot’s. He had received a similar wound moments before.

Winter looked at Knot. He wasn’t smiling, but Winter knew him well enough to know that he wouldn’t. But he was content. His eyes were peaceful.

“By the power of the Nine, whom Canta chose,” the priestess continued, “whose power flows in me, I bestow these blessings upon you.”

The words buzzed in Winter’s head, and she found it difficult to concentrate. She was new, now. For better or worse, her life would be forever different.

“That you will love one another,” the priestess said.

Winter gazed out at the small chapel. Torches cast a flickering glow up into the rafters of the elongated gable roof, but left the wide wings of the building in shadow. Darrin and Eranda’s daughter Sena stood close by her. She was the only tiellan girl close enough to Winter’s age to serve as a handmaid, though still not much more than a child.

“That you will serve those around you.”

Lian and Darrin sat on the front row of polished, smooth benches, as did Eranda. Gord and Dent sat a few rows back. Winter could not thank everyone enough for coming, but she felt another pang of disappointment that the other pews were empty. It was irrational, she knew. She wasn’t even sure she wanted to go through with the ceremony, but she wanted more people there to watch? Yet, had the ceremony happened a few years ago, the chapel would have been packed with tiellans.

“That you will be protected from the Daemons of this world and beyond, and that your souls will never fade into Oblivion.”

Then, as if summoned by Winter’s thoughts, a group of men entered through the large set of doors at the back of the chapel.

These were not the type of wedding guests Winter had had in mind. It was hard to tell from this distance, but she could only assume that they were human; they all stood as tall or taller than Lian and Gord. Were they Kamites? She swallowed hard.

She counted six of them, each wearing a dark-green robe with a hood that hid his face in shadow. And they were armed. Swords and daggers, shields and spears.

Winter was vaguely aware of the priestess’s grip loosening. “What is the meaning of this intrusion?” the woman demanded.

The men stood for a moment, torchlight flickering on their robed frames. They looked back and forth from the priestess to the congregation.

Winter began to fear they truly were Kamites, advocates of the reinstatement of tiellan slavery, and, barring that, the death of all tiellans. They were not a popular group, nor a very public one, but rumors said they had a presence in Pranna.

One of the men, taller than the rest, stepped forward. “We aren’t exactly intruding,” he said, with a clipped, harsh accent. He sounded Rodenese. Not a Kamite, then. The Kamite order had not spread beyond Khale’s borders. Winter sighed, but not in relief. The Rodenese had other ways of dealing with tiellans.

The tall man removed his hood and walked towards the front of the chapel. He was ugly. His blond hair was thinning, his nose hooked and too large. A deep scar ran along one side of his face, from where one ear should have been to his cheek. “We should have been invited, after all,” he said. He reached the front of the chapel where Winter, Knot, and the priestess stood. He put his hand on Knot’s shoulder. “We’re old friends of Lathe, here.”

Winter looked at Knot, eyes wide. Was that his real name? Did these men know who Knot was?

Knot tightened his hold on Winter’s hand.

Bahc stood. “Knot, son, if you know these men—”

“I don’t,” Knot said, his voice soft. He kept his eyes on the man with the hand on his shoulder. “Best thing you can do right now, my lord, is turn around and walk out.”

The authority in Knot’s voice surprised Winter. She had heard him speak like that on the boat, when relaying Bahc’s orders, but otherwise he was calm, soft-spoken.

“Is that the best thing I can do right now… Knot?” The man’s eyes narrowed. “Suppose you’d know, wouldn’t you? Always seemed to know what was best for everyone else. Well, do you know what’s best for all of your friends, here, Knot? Do you know what’s best for your new bride? Give yourself up and no one gets hurt.”

Winter looked around nervously. What were these men doing? What was Knot doing? She felt frozen, as if watching the moment from far away, engrossed but unable to do anything.

The priestess obviously felt differently. “How dare you storm into a Holy Cantic—”

There was a flash of movement, and for a moment Winter thought the tall man had shoved the priestess. The woman gasped and stepped backwards. Winter looked back at the tall man, one of his arms still on Knot’s shoulder. In the other he clutched a dagger, dripping blood.

The priestess crashed to the floor.

“Damn shame,” the tall man said, still staring at Knot.

“Oh, Goddess,” Winter whispered.

The man looked at her, his face split by a scar and a grin. “Don’t think She’s here today. Maybe you should check back later.” He looked back at his men. “Take them!”

Winter was lost in the sudden chaos that followed. Her father stared at her, pale-faced, shouting for Eranda and Sena to flee. Gord, face red, rose up from his pew. The disciples scurried this way and that, shouting for the Goddessguard.

Knot pulled Winter towards him, his hands strong and sure. Some of the torches must have gone out, and the room was darker, the flickering orange light eerie. The only thing that brought Winter back to focus was Knot’s voice as he turned her towards him. His hands held her face, locking her gaze to his. She felt his blood on her cheek, still fresh from the priestess’s dagger. There was a glint in his eye she had never seen before, cold and sharp, like a flash of lightning on the water in a dark winter storm.

“I won’t let them hurt you,” he said.

Winter shivered at the sound of his voice.

Behind Knot, Winter saw a shadow and a glint of steel—one of the robed men charging them with a sword. Before she had time to scream, Knot spun, grabbed the man by the wrist, and somehow used the robed man’s momentum to spin full circle and slam him face first into the floor. Knot bent the man’s arm back, and Winter heard a horrible snap. Her breath caught in her chest, and she stepped away. The whole thing hadn’t taken more than a second. The torchlight flickered; half of Knot’s face was drowned in shadow.

Perhaps the light had tricked Winter’s vision. And yet, there was the robed man, groaning on the floor. Knot stared at his own hands.

“Knot,” she said, “how…?”

He looked up, his eyes wide. He shook his head. “I don’t know.” His voice was barely a whisper. Then someone screamed and Knot turned away, towards the chaos.

The tall man held one of the disciples in front of Knot, a dagger at her throat. Behind him, another disciple lay on the floor, blood dripping from her mouth or her nose, Winter wasn’t sure which. People were shouting, the disciples screaming.

Then Winter heard her father.

Bahc was lying on the floor, groaning and clutching his belly. He looked up at her, but Winter could not see his expression. The room was too dark, and shadows obscured his face. Blood seeped between his fingers. One of the dark-clad men stood above him.

Winter screamed and rushed towards Bahc, but someone grabbed her. A dirty hand covered her mouth and an arm locked around her neck. She felt her own breath trapped in the hand as she screamed, and a wetness against her cheeks. Whether it was Knot’s blood or her own tears, she wasn’t sure. She struggled vainly, but could barely move. The arm tightened around her neck, and her head felt like it was about to burst, both heavy and light at the same time. Looking around wildly, she saw Knot. Two of the robed men lay on the ground near him. She saw the cold gleam in his eye again. Knot lunged, his palm jutting up into the face of a robed man. The man’s head snapped back, and then Knot was moving too quickly for Winter to keep track of him.

Years ago, Winter’s father had caught a dragon-eel in a net of deepfish. She remembered him guiding her tentatively to the water-hold where the net had been released. Pointing down into the hold, he told her to watch a real predator in action. “Where is it?” she had asked. There were hundreds of flopping, floundering deepfish, their wide, flat bodies bouncing in the shallow water. Winter couldn’t see any dragon-eel. As far as she knew, they weren’t even real. Then, faster than she could follow, a slender, sinuous black shape had burst forth from the water, shredding deepfish with razor teeth. The eel was in one corner of the hold, and then the other, then in the middle, then leaping through the air, wreaking chaos among the struggling fish. “It isn’t eating them,” Winter had said. “Why isn’t it eating them?” “Because a dragon-eel doesn’t kill for survival,” her father had said. “A dragon-eel kills for the pleasure of it.” The water had already turned red with blood, and Winter had backed away slowly, never wanting to see a dragon-eel again.

Now, as the man’s hold around her neck tightened and blackness threatened the corners of her vision, that image of the dragon-eel was all she could think of as Knot wrought havoc, a blur of brutality in a room of helpless, floundering deepfish.

2

KNOT WAS AFRAID.

The fear itself didn’t trouble him. No, the dark pull from his throat to his gut was a familiar feeling. What troubled him was that he wasn’t afraid of the men who had just attacked his wedding; he was afraid of how easy it’d been to kill them.

The frozen wind from the gulf whipped through Knot’s cloak as he made his way to Darrin and Eranda’s home. Winter was unconscious in his arms, a curious warmth against the chilly air. Snow had begun to fall, white flakes settling and then disappearing on Winter’s face. The snow was peaceful, and that was cruel.

Knot had left nine bodies at the chapel. The robed men were unknown to him, and he had no idea how he he’d dispatched them. Yet he knew, as soon as he realized the men were a threat, that he could defeat them. He’d known it in his bones, on some level far deeper than his mind. His body had done the work quickly and easily.

The priestess and two of her disciples were both dead, killed by the robed men. The other disciple had run away in the chaos. Knot had killed four of the intruders, while Lian, Gord, and Dent had taken down another; Dent had lost his life in the process. The tall, scarred man, the one who had first approached Knot, had escaped.

And there was Bahc.

Knot knew he should never have stayed in Pranna. But he’d stayed anyway, and now the guilt carved at him.

He’d stayed because Bahc was kind. And because Bahc’s daughter was beautiful. He was ashamed to admit it, but there it was. He’d also stayed because he had nowhere else to go. His memories of whatever life he’d had before waking up in Bahc’s house were incomprehensible. A jumble of impossible images, faces he couldn’t name, blurry and dark.

But, most of all, he’d stayed because of the life he thought he could make here. These were simple folk, and Knot was drawn to that simplicity, living day by day on what he caught in the freezing gulf. He liked tiellan tradition, conservative and unobtrusive. Whether the rift between humans and tiellans had bothered him in the past, Knot didn’t know. But it didn’t matter now. He liked the pragmatic way they looked at things. Made the best they could out of the hand life had dealt them.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!