2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Skyline

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

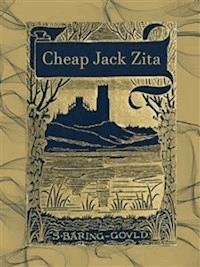

WHAT was the world coming to? The world—the centre of it—the Isle of Ely? What aged man in his experience through threescore years and ten had heard of such conduct before? What local poet, whose effusions appeared in the 'Cambridge and Ely Post,' in his wildest flights of imagination, conceived of such a thing? Decency must have gone to decay and been buried. Modesty must have unfurled her wings and sped to heaven before such an event could become possible. Where were the constables? Were bye-laws to become dead letters? Were order, propriety, the eternal fitness of things, to be trampled under foot by vagabonds? In front of the cathedral, before the Galilee,—the magnificent west porch of the minster of St. Etheldreda,—a Cheap Jack's van was drawn up. Within twenty yards of the Bishop's palace, where every word uttered was audible in every room, a Cheap Jack was offering his wares. Effrontery was, in heraldic language, rampant and regardant.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

S. Baring-Gould

Cheap Jack Zita

Table of contents

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

CHAPTER XV

CHAPTER XVI

Footnotes

CHAPTER XVII

CHAPTER XVIII

CHAPTER XIX

CHAPTER XX

CHAPTER XXI

CHAPTER XXII

CHAPTER XXIII

CHAPTER XXIV

CHAPTER XXV

CHAPTER XXVI

CHAPTER XXVII

CHAPTER XXVIII

CHAPTER XXIX

CHAPTER XXX

CHAPTER XXXI

CHAPTER XXXII

CHAPTER XXXIII

CHAPTER XXXIV

CHAPTER XXXV

CHAPTER XXXVI

CHAPTER XXXVII

CHAPTER XXXVIII

CHAPTER XXXIX

CHAPTER XL

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

THE FLAILS

'NOW, here's a chance you may never have again—a chance, let me tell you, you never will have again.' She extended in both hands packages of tea done up in silvered paper. 'The general public gets cheated in tea—it does—tremenjous! It is given sloe leaves, all kinds of rubbish, and pays for it a fancy price. Father, he has gone and bought a plantation out in China, and has set over it a real mandarin with nine tails, and father guarantees that this tea is the very best of our plantation teas, and he sells it at a price which puts it within the reach of all. Look here!' she turned a parcel about; 'here you are, with the mandarin's own seal upon it, to let every one know it is genuine, and that it is the only genuine tea sent over.'

'Where's the plantation, eh, girl?' jeered a boy from the grammar school.

'Where is it?' answered the girl, turning sharply on her interlocutor. 'It's at Fumchoo. Do you know where Fumchoo is? You don't? and yet you sets up to be a scholar. It is fifteen miles from Pekin by the high road, and seven and a half over the fields. Go to school and look at your map, and tell your master he ought to be ashamed of himself not to ha' made you know your geography better. Now, then, here's your chance. Finest orange-flower Pekoe at four shillings. Beat that if you can.' No offers. 'I am not coming down in my price. Don't think that; not a farthing. Four shillings a pound; but I'll try to meet you in another way. I keep the tea in quarter-pound parcels as well. Perhaps that'll meet your views—and a beautiful pictur' of Fumchoo on the cover, with the Chinamen a-picking of the tea leaves. What! no bidder?'

There ensued a pause. Every one expected that the girl would lower the price. They were mistaken. She went back into the van and produced a roll of calico. Then ensued an outcry of many voices: 'Tea! give us some of your tea, please.' In ten minutes she had disposed of all she had.

'There, you see,' said Zita, 'our supply runs short. In Wisbeach the Mayor and Corporation bought it, and at Cambridge all the colleges had their supplies from us. That's why we're run out now. Stand back, gents.'

This call was one of caution to the eager purchasers and tempted lookers-on.

Tawdry Fair was for horses and bullocks, and a drove of the latter was being sent along from the market-place towards Stuntney. For a while the business of the sale was interrupted. One audacious bullock even bounded into the Galilee, another careered round the van; one ran as if for sanctuary to the Bishop's palace. Zita seized the occasion to slip inside the van. Her father was on the low seat, leaning his head wearily on his hand, and his elbow on his knee.

'How are you now, dad?'

'I be bad, Zit—bad—tremenjous.'

'Had you not best see a doctor?'

He shook his head.

'It'll pass,' said he; 'I reckon doctors won't do much for me. They're over much like us Cheap Jacks—all talk and trash.'

'This has been coming on some time,' observed the girl gravely. 'I've seen for a fortnight you have been poorly.'

Then, looking forth between the curtains which she had lowered, she saw that the bullocks were gone, and that the cluster of people interested in purchases had re-formed round her little stage.

'I say,' shouted a chorister, 'have you got any pocket-knives?'

'Pocket-knives by the score, and razors too. You'll be wanting a pair of them in a fortnight.'

Whilst Zita was engaged in furnishing the lads with knives, the Bishop retired from the upstairs window to his library, where he seated himself in an easy-chair, took up a pamphlet, and went up like a balloon inflated with elastic gas into theologic clouds, where controversy flashed and thundered about his head, and in this, his favourite sphere, the Right Reverend Father forgot all about the Cheap Jack, and no longer felt concern at his having been misrepresented as grovelling before a prince of the blood royal in a red waistcoat.

At the same time, also, a plot concerning Zita was being entered into by a number of young fen-men who had come to Tawdry Fair to amuse themselves, and had been arrested by the attractions of the Cheap Jack's van.

Whatever those attractions might have been whilst the man was salesman, they were enhanced tenfold when his place was occupied by his daughter. Some whispering had gone on for five minutes, and then with one consent they began to elbow their way forward till they had formed an innermost ring around the platform. But this centripetal movement had not been executed without difficulty and protest. Women, boys, burly men were forced to give way before the wedge-like thrusts inwards of the young men's shoulders, and they remonstrated, the women shrilly, the boys by shouts, the men with oaths and blows. But every sort of resistance was overcome, all remonstrances of whatever sort were disregarded, and Zita suddenly found herself surrounded by a circle of sturdy, tall fellows, looking up with faces expressive of mischief.

That something more than eagerness to purchase was at the bottom of this movement struck Zita, and for a moment she lost confidence, and faltered in her address on the excellence of some moth-eaten cloth she was endeavouring to sell.

Then one round-faced, apple-complexioned young man worked himself up by the wheel of the van, and, planting his elbows on the platform, shouted, 'Come, my lass, at what price do you sell kisses?'

'We ha'n't got them in the general stock,' answered Zita; 'but I'll ask father if he'll give you one.'

A burst of laughter.

'No, no,' shouted the red-faced youth, getting one knee on the stage. 'I'll pay you sixpence for a kiss—slick off your cherry lips.'

'I don't sell.'

'Then I'll have one as a gift.'

'I never give away nothing.'

'Then I'll steal one.'

The young fellow jumped to his feet on the platform. At the signal the rest of the youths began to scramble up, and in a minute the place was invaded, occupied, and the girl surrounded. Cheers and roars of laughter rose from the spectators.

'Now, then, you Cheap Jack girl,' exclaimed the apple-faced youth. 'Kisses all round, three a-piece, or we'll play Old Harry with the shop, and help ourselves to its contents.'

The father of Zita, on hearing the uproar, the threats, the tramp of boots on the stage, staggered to his feet, and, drawing back the curtains, stood holding them apart, and looking forth with bewildered eyes. Zita turned and saw him.

'Sit down, father,' said she. 'It's only the general public on a frolic.'

She put her hand within and drew forth a stout ashen flail, whirled it about her head, and at once, like grasshoppers, the youths leaped from the stage, each fearing lest the flapper should fall on and cut open his own pate. The last to spring was the apple-faced youth; he was endeavouring to find some free space into which to descend, when the flapper of the flail came athwart his shoulder-blades with so sharp a stroke, that, uttering a howl, he plunged among the throng, and would have knocked down two or three, had they not been wedged together too closely to be upset.

Then ensued cries from those hurt by his weight as he floundered upon them; cries of 'Now, then, what do you mean by this? Can't you keep to yourself? This comes of your nonsense.'

Zita stood erect, leaning on the staff of the flail, looking calmly round on the confusion, waiting till the uproar ceased, that she might resume business. As she thus stood, her eye rested on a tall, well-shaped man, with a tiger's skin cast over his broad shoulders, and with a black felt slouched hat on his head. His nose was like the beak of a hawk. His eyes were dark, piercing, and singularly close together, under brows that met in one straight band across his forehead.

The moment this man's eye caught that of Zita, he raised his great hat, flourished it in the air, exposing a shaggy head with long dark locks, and he shouted, 'Well done, girl! I like that. Give me a pair of them there ashen flails, and here's a crown for your pluck.'

'I haven't a pair,' said the girl.

'Then I'll have that one, with which a little gal of sixteen has licked our Fen louts. I like that.'

'I'll give you a crown for that flail,' called another man, from the farther side of the crowd. 'Here you are—a crown.'

This man was fair, with light whiskers—a tall man as well as the other, and about the same age.

'I'll give you seven shillings and six—a crown and half a crown for that flail,' roared the dark man. 'I bid first—I want that flail.'

'Two crowns—ten shillings,' called the fair man. 'I can make a better offer than Drownlands— not as I want the flail, but as Drownlands wants it, he shan't have it.'

'Twelve and six,' roared the dark man. 'Gold's no object with me. What I wants I will have.'

The lookers-on nudged each other. A young farmer said to his fellow, 'Them chaps, Runham and Drownlands, be like two tigers; when they meet they must fight. We shall have fun.'

'You are a fool!' shouted the fair man,—'a fool—that is what I think you are, to give twelve and six for what isn't worth two shillings. I'll let you have it at that price, that you may become the laughing-stock of the Fens.'

The flail was handed out of the van to the man called Drownlands, Zita received a piece of gold and half a crown in her palm. She retired into the waggon, and immediately reappeared with a second flail.

'Here is another, after all,' said she; 'I didn't think I had it.'

'I'll take that to make the pair,' said Drownlands; 'but as you've done me over the first, I think you should give me this one.'

'I done you!' exclaimed Zita; 'you've done yourself.'

'She's right there,' observed a man in the crowd. 'Them tigers—Runham and Drownlands—would fight about a straw.'

'Are you going to hand me over that flail?' asked the dark purchaser.

Zita remained for a moment undecided. She had in verity made an unprecedented price with the first, and she was half inclined to surrender the second gratis, but to give and receive nothing was against the moral code of Cheap Jacks from the beginning of Cheap Jacking. Whilst she hesitated, holding the flail in suspense, and with a finger on her lips, the fair man yelled out—

'Don't let the blackguard have it. I'll have it to spoil the pair for him, and for no other reason.'

'I will have it, you scoundrel!' howled the dark man. 'I have as much gold as ever you have. I don't care what I spend. Here, girl! a crown to begin with.'

'Seven and six,' shouted Runham.

'Ten shillings,' cried Drownlands.

'Fifteen shillings!' exclaimed the fair man. Then, seeing that his rival was about to bid, he yelled, 'A guinea!' at the same moment that the other called, 'A pound!'

'It is yours,' said the girl to the man Runham, and she handed him the flail. She saw that the passions of the two men were roused, and she deemed it desirable to close the scene, lest a fight should ensue, in which, possibly, she might lose the money that had been offered.

Runham, flourishing his flail over his head, and throwing out the flapper in the direction of Drownlands, said, 'There, now! Who can say but what I'm the best off of the two? Mine cost me a guinea, and his beggarly flail not above twelve and six. I am the better man of the two by eight and six.'

He felt in his pockets and drew forth a guinea.

'There, you Cheap Jack girl—here's your money all in gold. I'm the better man of the two by eight and six. I've beat Drownlands like a gentleman.'

Some one looking on in the crowd said, 'A pair o' flails and a pair o' fools at the end o' them, as don't know what is the vally o' their money. Never since the creation of the world was flails sold at that price, and never will be again.'

'And never would have been, or never could have been, anywhere but among fen-tigers,' said another.

'I'll tell'y what,' observed the first; 'this ain't the end o' the story.'

'No—I guess not. It's the beginnin' rather of a mighty queer tale.'

CHAPTER III

TWO CROWNS

A STRANGELY interesting city is Ely.Unique in its way is the metropolis of the Fens; wonderful exceeding it must have been in the olden times when the fen-land was one great inland sea, studded at wide intervals with islets as satellites about the great central isle of Ely. It was a scene that impressed the imagination of our forefathers. Stately is the situation of Durham, that occupies a tongue of land between ravines. It has its own unique and royal splendour. But hardly if at all inferior, though very different, is the situation of Ely. The fens extend on all sides to the horizon, flat as the sea, and below the sea level. If the dykes were broken through, or the steam pumps and windmills ceased to work, all would again, in a twelvemonth, revert to its primitive condition of a vast inland sea, out of which would rise the marl island of Ely, covered with buildings amidst tufted trees, reflecting themselves in the still water as in a glass. Above the roofs, above the tree-tops, soars that glorious cathedral, one of the very noblest, certainly one of the most beautiful, in England—nay, let it be spoken boldly—in the whole Christian world. It stands as a beacon seen from all parts of the Fens, and it is the pride of the Fens.

Ely owes its origin to a woman—St. Etheldreda—flying from a rude, dissolute, and drunken court. She was the wife first of Tombert, a Saxon prince in East Anglia, then of Egfrid of Northumbria. Sick of the coarse revelry, the rude manners of a Saxon court, Etheldreda fled and hid herself in the isle of Ely, where she would be away from men and alone with God and wild, beautiful nature.

Whatever we may think of the morality of a wife deserting her post at the side of her husband, of a queen abandoning her position in a kingdom, we cannot, perhaps, be surprised at it. A tender, gentle-spirited woman after a while sickened of the brutality of the ways of a Saxon court, its drunkenness and savagery, and fled that she might find in solitude that rest for her weary soul and overstrained nerves she could not find in the Northumbrian palace. This was in the year 673. Then this islet was unoccupied. It has been supposed that it takes its name from the eels that abounded round it; we are, perhaps, more correct in surmising that it was originally called the Elf-isle, the islet inhabited by the mythic spiritual beings who danced in the moonlight and sported over the waters of the meres.

This lovely island, covered with woods, surrounded by a fringe of water-lilies, gold and silver, floating far out as a lace about it, became the seat of a great monastery. Monks succeeded the elves.

King Canute, the Dane, was seized with admiration for Ely, loved to visit it in his barge, or come to it over the ice. It is said that one Candlemas Day, when, as was his wont, King Canute came towards Ely, he found the meres overflowed and frozen. A 'ceorl' named Brithmer led the way for Canute's sledge over the ice, proving the thickness of the ice by his own weight. For this service his lands were enfranchised.

On another occasion the king passed the isle in his barge, and over the still and glassy water came the strains of the singing in the minster. Whereupon the king composed a song, of which only the first stanza has been preserved, that may be modernised thus:—

'Merry sang the monks of Ely

As King Knut came rowing by.

Oarsmen, row the land more near

That I may hear their song more clear.'

Ely, although it be a city, is yet but a village. The houses are few, seven thousand inhabitants is the population, it has two or three parish churches, and the cathedral, the longest in Christendom. The houses are of brick or of plaster; and a curious custom exists in Ely of encrusting the plaster with broken glass, so that a house-front sparkles in the sun as though frosted. All the roofs are tiled. The cathedral is constructed of stone quarried in Northamptonshire, and brought in barges to the isle.

Ely possesses no manufactures, has almost no neighbourhood, stands solitary and self-contained. On some sides it rises rapidly from the fen, on others it slopes easily down. A singular effect is produced when the white mists hang over the fen-land for miles and miles, and the sun glitters on the island city. Then it is as an enchanted isle of eternal spring, lost in a wilderness of level snow. Or again, on a night when the auroral lights flicker over the heavens, here red, there silvery, and against the glowing skies towers up this isle crowned with its mighty cathedral, then, verily, it is as though it were a scene in some fairy tale, some magic creation of Eastern fantasy.

A girl was sauntering through the wide, grass-grown streets of Ely. During the fair the streets were full of people—nay, full is not the word—were occupied by people more or less scattered about them. It would take a vast throng, such as the fens of Cambridgeshire cannot supply, to fill these wide spaces.

The girl was tall and handsome, rather masculine, with a cheerful face. She had very fair hair, a bright complexion, and eyes of a dazzling blue—a blue as of the sea when rippling and sparkling in the midsummer sun. She was plainly dressed in serge of dark navy blue, with white kerchief about her neck, a chip hat-bonnet and blue ribbons in it. Her skirts were somewhat short, they exposed neat ankles in stockings white as snow, and strong shoes. A fen-girl must wear strong shoes, she cannot have gloves on her feet.

'Jimminy!' said the girl, as she turned her pocket inside out. 'Not one penny! Poor Kainie is the only girl at the fair without a sweetheart, the only child without a fairing. No one to treat me! Nothing to be got for nothing. Jimminy! I don't care.' Then she began to sing:—

'Last night the dogs did bark,

I went to the gate to see.

When every lass had her spark,

But nobody comes to me.

And it's Oh dear! what will become of me?

Oh dear, what shall I do?

Nobody coming to marry me,

Nobody coming to woo.

My father's a hedger and ditcher,

My mother does nothing but spin,

And I am a pretty young girl,

But the money comes slowly in'—

Then suddenly she confronted the fair-haired farmer Runham, coming out of a tavern, with the flail over his shoulder. A little disconcerted at encountering him, she paused in her song, but soon recovered herself, and began again at the interrupted verse:—

'My father's a hedger and ditcher,

My mother'—

'Kainie! Are you beside yourself, singing like a ballad-monger in the open street?'

The man's face was red, whether with drink, or that the sight of the girl had brought the colour into his face, Kainie could not say. His breath smelt of spirits, and she turned her head away.

'It's all nonsense,' she said. 'My mother is dead—is dead—and I am alone. I don't know, I don't see why I should not sing; I want a fairing, and have no money. I'll go along singing, "My father's a hedger and ditcher," and then some charitable folk will throw me coppers, and I shall get a little money and buy myself a fairing.'

'For heaven's sake, do nothing of the kind. Here—rather than that—here is a crown. Take that. What would the Commissioners say if they were told that you went a ballad-singing in the streets of Ely at Tawdry Fair? They would turn you out of your mill. I am sure they would. Here, Kainie, conduct yourself respectably, and take a crown.'

He pressed the large silver coin into her hand, and hurried away.

'That's brave!' exclaimed the girl, snapping her fingers. 'Now I can buy my fairing. Now, all I want is a lover.

"Nobody coming to marry me,

Nobody coming to woo!"

Jimminy! I must not do that! I've taken a crown to be mum. Now I'm a young person of respectability—I've money in my pocket. Now I must look about me and see what to buy. I'll go to the Cheap Jack. How do you do, uncle?'

She addressed the dark-haired man Drownlands, who had just turned the corner, with his flail over his shoulder. He scowled at the girl, and would have passed her without a word, but to this she would not consent.

'See! see!' said she, holding up the crown she had received. 'I was just going along sighing and weeping because I had no money, not a farthing in my pocket, not a lover at my side to buy me anything. Then came some one and gave me this—look, Uncle Drownlands! Five shillings!'

'So—going in bad ways?'

'What is the harm? I was ballad-singing. Then he came and gave me a crown.'

'You ballad-singing!'

'Yes; how else can I get money? I'm a poor girl, owned by nobody, for whom nobody cares.'

'You will bring disgrace—deeper disgrace on the family—on the name.'

'Not I; I'm honest. If I am given five shillings, may I not receive it? Master Runham gave me the money to make me shut my mouth. I was singing

"My father's a hedger and ditcher,

My mother"'—

'For heaven's sake, silence!' said Drownlands angrily. 'If you will hold your tongue, I will give you a couple of shillings.'

'A couple of shillings! And I'm your own niece, and have your name.'

'More shame to you—to your mother!' exclaimed the farmer bitterly.

The girl suddenly dropped her head, and her brow became crimson.

'Not a word about my dear mother—not a stone thrown at her,' she said in a low tone.

'Well, no ballad-singing. Take heed to yourself. You are wild and careless.'

'Much you think of me! much you care for me!'

'Begone! You are a disgrace to me—your existence is a disgrace. Take a crown and spend it properly. You shall have nothing more from me. As Runham gave you five shillings, it shall not be said that I gave you less.'

He handed her the coin, and with a scowl passed on.

Kainie remained for a moment musing, with lowered eyes. Then she raised her head, shook it, as though to shake off the sadness, the humiliation that had come on her with the words of Drownlands, and hummed—

'Nobody coming to marry me,

Nobody coming to woo.'

'What! Kainie!'

The words were those of a young man, heavy-browed, pale, somewhat gaunt, with long arms.

'Oh, Pip!—Pip!—Pip!'

'What is the matter, Kainie?'

'Pip, I'm the only girl here without her young man. It is terrible—terrible; and see, Pip, I've got two crowns to spend, and I don't know what to spend them on. There is too much money here for sweetie stuff; and as for smart ribbons and bonnets and such like, it is only just about once in the year I can get away from the mill and come into town and show myself. It does seem a waste to spend a couple of crowns on dress, when no one can see me rigged out in it. What shall I do, Pip?—you wise, you sensible, you dear Pip.'

The young man, Ephraim Beamish, considered; then he said—

'Kainie, I don't like your being alone in Red Wings. Times are queer. Times will be worse. There is trouble before us in the Fens. Things cannot go on as they are—the labouring men ground down under the heels of the farmers, who are thriving and waxing fat. I don't like you to be alone in the windmill; you should have some protector. Now, look here. I've been to that Cheap Jack van, and there's a big dog there the Cheap Jackies want to sell, but there has been no bid. Take my advice, offer the two crowns for that great dog, and take him home with you. Then I shall be easy; and now I am not that. You are too lonely—and a good-looking girl like you'—

'Pip, I'll have the dog.' She tossed the coins into the air. 'Here, crownies, you go for a bow-wow.'

CHAPTER IV

ON THE DROVE

THERE is not in all England—there is hardly in the world—any tract of country more depressing to the spirits, more void of elements of loveliness, than the Cambridgeshire Fens as they now are.

In former days, when they were under water—a haunt of wildfowl, a wilderness of lagoons, a paradise of wild-flowers—when they teemed with fish and swarmed with insect life of every kind—when theeysor islets, Stuntney, Shipey, Southconey, Welney, were the sole objects that broke the horizon, rising out of the marshes, rich with forest-trees—then the Fens were full of charm, because given over to Nature. But the industry of man has changed the character and aspect of the Fens. The meres have been pumped dry, the bogland has been drained. Where the fowler used to boat after wild duck, now turnips are hoed; where the net was drawn by the fisherman, there wave cornfields.

In former times, for five-and-twenty miles north of Ely, one rippling lake extended, and men went by boat over it to the sand-dune that divided it from the sea at King's Lynn. To the west a mighty mere stretched from Ely to Peterborough. To the east lay a tangle of lake and channel, of marsh and islet.

Until about a hundred years ago, men lived in houses erected on platforms sustained upon piles above the level of the water. Walls and roofs of these habitations were thatched and wattled with reeds. From the door a ladder conducted to a boat. In these houses there were hearths, but no chimneys. The smoke escaped as best it might through the thatch, or under the gables. During the winter the fen-men picked up a livelihood fishing and fowling. In summer they cultivated such patches of peat soil as appeared above the surface of the water. There were no roads; men went from place to place by water, in boats or on skates.

In the reign of James I. Ben Jonson wrote his play 'The Devil is an Ass.' Into this play he introduced a speculator—a starter of bogus companies, by name Meercraft, and one of this man's schemes was the draining of the Fens.

The thing is for recovery of drown'd land,

Whereof the Crown's to have a moiety,

If it be owner; else the Crown and owners

To share that moiety, and the recoverers

To enjoy the t'other moiety for their charge,

* * * * * * which will arise

To eighteen millions, seven the first year.

I have computed all, and made my survey

Unto an acre; I'll begin at the pan,

Not at the skirts, as some have done, and lost

All that they wrought, their timberwork, their trench,

Their banks, all borne away, or else filled up

By the next winter. Tut, they never went

The (right) way. I'll have it all.

A gallant tract of land it is;

'Twill yield a pound an acre;

We must let cheap ever at first.'

Jonson introduced this Meercraft as a caution to the people of his day against being induced to sink money in such ventures, which he regarded as impossible of realisation. Nevertheless, what Jonson disbelieved in has been accomplished. The work begun in 1630, was interrupted by the Civil Wars, resumed afterwards, was carried on at considerable outlay and with great perseverance, till at the beginning of the present century the complete recovery of the Fens was an accomplished fact.

Great was the cost of the undertaking, and those who had invested in it wearied of the calls on their purses; land, or rather water, owners were discouraged, and were ready to part with rights and possessions that hardly fetched a shilling an acre, and which instead of being drained itself seemed to be draining their pockets. Long-headed fen-men saw their advantage, and bought eagerly where the owners sold eagerly. The new canals carried off the water, the machines set in operation discharged the drainage into the main conduits, and soil that for centuries had been worthless became auriferous. No more magnificent corn-growing land was to be found in England. None in Europe might compare with it, save the delta of the Danube and the richest alluvial tracts in South Russia. The fen-men made their fortunes before they had learned what to do with the fortunes they made. Money came faster than they found means to spend it.

To this day many of the wealthiest owners are sons or grandsons of half-wild fen-slodgers. There are no villages in the Fens apart from such as are clustered on widely dispersed islets. There are no old picturesque farmhouses and cottages. Everything is new and ugly. There are no hedges, no walls, for there is no stone in the country. There are no trees, save a few willows and an occasional ash, from whose roots the soil has shrunk. The surface of the land is sinking. As the fen is drained, the spongy soil contracts, and sinks at the rate of two inches in the year. Consequently houses built on piles are left after fifty years some eight feet above the surface, and steps have to be added to enable the inmates to descend from their doors.

The rivers slide along on a level with the top storeys of the houses, and the only objects to break the horizon are the windmills that drive the water up from the dykes into the canals.

There are no roads, as there is no material of which roads can be made. In place of roads there are 'droves.' A drove is a broad course, straight as an arrow, by means of which communication is had between one farm and another, and people pass from one village to another.

These droves have ditches, one on each side, dense in summer with bulrushes. No attempt is made to consolidate the soil in these droves other than by harrowing and rolling them in summer. In winter they are bogs, in summer they are dust—dust black, impalpable. Wheeled conveyances can hardly get along the droves in winter, or wet weather, as the wheels sink to the axles.

The canal banks, however, are solid, compacted of stiff clay, and as they are broad, so as to resist the pressure of the water they contain between them, their tops make very tolerable paths, and roads for those on horseback. But no wheeled vehicle is suffered to use the bank tops, and to prevent these banks from being converted into carriage roads, barriers are placed across them at intervals, which horses with riders easily leap.

At one of the Cambridge Assizes a poor man, a witness in court, when asked his profession, answered,—'My lord, I am a banker.' The judge, turning very red, said, 'No joking here, sir.' 'But Iama banker and nothing else,' protested the witness. He was, in fact, one of the gang of men maintained for the reparation of the canal banks.

The reader must be given some idea of the manner in which this vast level region is drained. It is cut up into large squares, and each square is a field that is surrounded by dykes. These dykes are in communication with one another, and all lead to adrainorload, that is to say, to a channel of water of a secondary size, that lies at the level of a few feet above the dykes. To convey the water from the ditches into the drains, windmills are erected, that work machinery which throws the water out of the ditches up hill into the loads. These loads or drains run to the canal at intervals of two miles; and when the drain reaches the canal bank, then a pump of great power forces the water of the load to a still higher level, into the main artery through which it flows to the sea. On the canals are lighters, and these, rather than waggons, serve for the conveyance of farm produce to the markets. Water is the natural highway in the fen-land.

The short October day had closed in. The fen lay black, streaked with steely bands—the dykes that reflected the grey sky.

On the right hand was a bank rising some fourteen feet above the roadway; it was the embankment of the river or canal that goes by the name of the Lark. Above it, some wan stars were flickering. On the left hand the fen stretched away into infinity, the horizon was lost in fog.

The Cheap Jack's horse was crawling, reeling along the drove under the embankment, the van plunging into quagmires, lurching into ruts. The horse strained every muscle and drew it forward a few yards, then sighed, hung his head, and remained immovable. Once again he nerved himself to the effort, and as the van started, its contents tinkled and rattled. The brute might as well have been drawing it across a ploughed field. Again he heaved a heavy sigh, and then finally abandoned the effort.

The Cheap Jack had got out of the conveyance. He was unwell, too unwell to walk, but he could not think of adding his weight to that the poor horse was compelled to drag over what was not the apology for, but the mockery of a road.

'I say, Zit,' muttered he hoarsely, 'I wish now as we'd a' stayed overnight in Ely.'

'I wish we had, father. And we could have afforded it; we've made fine profits in Ely—tremenjous.'

The man did not respond. He trudged and stumbled on.

< [...]