9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

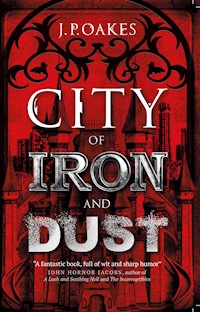

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

In this fast-paced dark fantasy, the fae seek to rebel against their goblin oppressors over one long bloody night."A fantastic book, full of wit and sharp humor, City of Iron and Dust careens through a modernized faerie at a breakneck pace, full of verve and unforgettable characters. Oakes spins a smart, electric, and sometimes snarky tale, showing that the beating heart of modern fantasy is alive and well." – John Hornor Jacobs, author of A Lush and Seething Hell and The IncorruptiblesThe Iron City is a prison, a maze, an industrial blight. It is the result of a war that saw the goblins grind the fae beneath their collective boot heels. And tonight, it is also a city that churns with life. Tonight, a young fae is trying to make his fortune one drug deal at a time; a goblin princess is searching for a path between her own dreams and others' expectations; her bodyguard is deciding who to kill first; an artist is hunting for his own voice; an old soldier is starting a new revolution; a young rebel is finding fresh ways to fight; and an old goblin is dreaming of reclaiming her power over them all. Tonight, all their stories are twisting together, wrapped up around a single bag of Dust―the only drug that can still fuel fae magic―and its fate and theirs will change the Iron City forever.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Praise for City of Iron and Dust:

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Let Me Tell You a Fairy Story

1 Three Assholes Walk Into a Bar

2 Old Dogs. New Tricks

3 Enter the McGuffin

4 Rebels with Causes

5 Dusted

6 Knull and Void

7 And Away We Go

8 Fight Night

9 Making Plans Like They Matter

10 Iron Fists and Lead Feet

11 Making It Worse

12 When the Bodies Hit the Floor

13 That’s Another Fine Mess You’ve Gotten Me Into

14 Of Romance and Rage

15 Realizations and Repercussions

16 And Then It All Goes to Shit

17 Life is Always Fatal

18 The View from Rock Bottom

19 And They All Lived Happily Ever After

20 Wasted Youth

Epilogue: A Cinderella Story

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

Praise for

City of Iron and Dust:

“A fantastic book, full of wit and sharp humor, City of Iron and Dust careens through a modernized faerie at a breakneck pace, full of verve and unforgettable characters. Oakes spins a smart, electric, and sometimes snarky tale, showing that the beating heart of modern fantasy is alive and well.”—JOHN HORNOR JACOBS, author of A Lush and Seething Hell and The Incorruptibles

“I truly wish there were more fantasies written with this verve and steel. I don’t think I’ve loved a book this hard in quite a while.”—T. FROHOCK, author of the Los Nefilim series

“A wonderful mash-up fantasy with a dash of Carl Hiaasen, a mad scramble through a burning city for the ultimate prize. Fans of Daniel Polansky’s Low Town or Robert Jackson Bennett’s City of Stairs will enjoy this one.”—DJANGO WEXLER, author of Ashes of the Sun

“A hard-boiled, phantasmagoric fable of blasted myths and desiccated dreams exploding into bloody revolution. Epic, intimate and one-of-a-kind!”—DALE LUCAS, author of The Fifth Ward series

“City of Iron and Dust is a bloody, brutal and bold novel featuring all manner of fantastical creatures... but it’s really about being human. Oakes has crafted a tale that is as entertaining as it is wonderfully original.”—TIM LEBBON, author of Eden

“Oakes delivers wit, grit, and magic in spades, all mixed together with a heap of heart-stopping action and relentless humor. Unforgettable.”—NATANIA BARRON, author of Queen of None

“I was sold on this ‘grim for all the cynical reasons’ fantasy novel by J.P. Oakes with the six words of the first chapter title. Well, two of the words weren’t that important. The point is that Oakes knows we’re tired of all the heroic and earnest and uplifting tropes, and that what we really want is something nasty and funny and thrilling to read.”—MARK TEPPO, author of The Cold Empty

“The Iron City is a singular dark fantasy creation that breathes with menace and decay. J.P. Oakes’ gallows humor and wit bring a sharp levity to the story that will leave you laughing, and then horrified at just what you were laughing about.”—PAUL JESSUP, author of The Silence That Binds

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

or your preferred retailer.

City of Iron and Dust

Print edition ISBN: 9781789097108

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789097115

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: July 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

© Jonathan Wood 2021. All rights reserved.

Jonathan Wood asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Tami, Charlie, and Emma

“The American Dream has run out of gas. The car has stopped.”

—J.G. Ballard

Let Me Tell You a Fairy Story

(or, It’s Not Epic if it Doesn’t Have a Prologue)

Once upon a time there was the world that was. And you’ll hear that it was golden, and that it was beautiful, and that it was everything else that everyone always says it used to be. Specific examples, however, will not be provided.

Once upon a time there was the world that was. And then it went away.

The goblins came from the North. In the world that was, this was something that happened from time to time, and this attack, like the others, was looked upon with something like pity and something like dismay. A few troops were sent to dismiss the problem, as they usually were.

But this was no longer the time that was. And the few troops were not victorious, and the goblins continued their march south.

In the wake of this defeat, the fae flung around recriminations: this was the result of poor leadership; this was the fault of some sidhe’s agenda, or this brownie’s ineptitude; this was all somebody else’s fault. The goblins did not care, though. The goblins kept on marching. So, more troops were sent.

And still this was not the time that was. This was new. This was a hundred goblin tribes sick of being relegated and subjugated finally united under the banner of one. And that one was Mab. And Mab swept the fae troops aside like so much dust collected at her feet.

Then the war was on in earnest. And perhaps it was a war of good against evil. But perhaps it wasn’t. Perhaps it depended whose side you were on.

But no matter whose side you were on, it was Mab who ended the war.

They called it Mab’s Kiss. Three great fae forest cities gone so quickly their inhabitants didn’t have the time to scream. Magic more powerful than any the fae had left. And right alongside those cities, the fae’s willingness to fight disappeared too.

And so, the unthinkable was thought, and the fae lost the war.

The goblins built cities of cold iron then, of steel and glass. They encased those cities in great metal walls. Inside them, they cut down every tree. They herded the fae into slums and forced them into factories. They bent their heads beneath the twin burdens of labor and poverty.

The fae cried out as it happened. Enclosed within these metropolises of iron, they reached out for their magic. But they felt nothing. They could do nothing. The great iron walls kept them cut off from the earth, and the trees, and all the magic they had once known. Their magic had been amputated.

But as the fae writhed, so the goblins thrived. They innovated. They built shopping malls, and microwave ovens, and combustion engines. They invented guns, and subcultures that celebrated guns. They aired 24/7 news channels. They sold each other mortgages.

And so, the world that was went away, and the world that is began. And in this new world, there was one city that rose far to the west. There was one city that gleamed bright across the stumps of a thousand felled trees. The Iron City.

In this city, in this new world, there are five towers, one for each of the great Goblin Houses. And everyone in this city—goblin and fae alike—looks up at them and knows in their hearts that these houses are the axle upon which all their lives spin.

Just because everybody believes a thing, though, does not mean that it is true. The end of the world that was should have proven that. Complacency, though, is such an easy sin.

Rather, there is another tower upon which all should look. This one is not so great. This one is dirty, and squalid, and nothing more than the stunted aspirations of a desperate developer who went to an early grave. Atop this tower is a penthouse, which—despite its name—is as small and filthy as the tower to which it belongs.

Inside, this penthouse is full of blood.

This is closer to the truth. This is closer to the core of it all.

Deeper into the apartment, beyond the still-cooling aftermath of violence, hidden away, still waiting to be found, is a package. It is a small thing, not even as big as a gym bag, and unassuming in the way such things often are.

It is a package bound in plastic wrap and brown tape. It is a package full of white powder, and it is the axle that the Iron City spins upon tonight. And as it turns, it ushers in not the world that was, nor the world that is, but the world that is yet to be, and tonight not everyone is destined to live happily ever after…

1

Three Assholes Walk Into a Bar

Jag

A bar. A dive. A neon sign glitching on and off above a burst of yellow light seen through a smeared windowpane. A bouncer hulking in a doorway—the type with more knuckles than IQ points. Probably half-dryad by the look of him, although his mother certainly wasn’t one of the willow-tree sprites that get all the press. The smell of wet asphalt and cigarette smoke. Brownies, kobolds, and sidhe bundling past, wishing they had enough money to go in. But no one in this part of the Iron City is particularly liquid right now. They haven’t been for the past fifty years. Prospects don’t look great.

Inside, a mad cram of bodies. Ruddy-faced kobolds. Sidhe in imperious shades of blue. Pixies scattered across the dance floor all the colors of a shattered rainbow. A shouting, clawing mass with one thing in mind: erasing the grind of the week with bad decisions, and the possibility to one day tell a story that starts with the phrase, “Don’t judge me, because I was obliterated at the time.”

The fae of the Iron City are at their shift’s end. They are at their wits’ end. They don’t appreciate the rhyme, even though the band on the stage are milking it for all they’re worth. A pixie on vocals, her hair half-shaved, the other half bright as summer lilacs. She’s screeching and screaming, throwing all of her adolescent energy into every word. And it’s immature, and it’s mostly wrong, but there’s still a beauty to her passion that half the preening fae with their pints of fermented nectar can’t wait to tell her about.

Behind her, a kobold has scavenged an old oak door from somewhere and is beating on it like it said something horrifying about his sister. He’s broad, and wearing a shirt to prove it, muscles emerging from the shaggy mane of red hair that obscures half his features.

The slender sidhe violinist who accompanies them is perhaps hampered by her own ennui. Still, attitude counts for a lot on stage and her dead-eyed stare from above knife-blade sharp cheekbones makes up a lot of ground.

The three of them have Jag transfixed.

Jag does not belong here. Jag’s neatly coiffed and perfectly trimmed hair don’t belong. Her clothes with their perfect lines and elegant stitching don’t belong. And Jag’s race definitely does not belong.

Jag is a goblin. She is obviously and painfully a goblin. She is green-skinned and sharp-featured. She has yellow eyes with slit pupils. She is long-fingered. And while she is taller and graced with more sidhe-like elegance than most of her kind, she is still, most undeniably, a goblin.

Jag is an oppressor in a bar of the oppressed.

Jag thinks she knows all this, of course. Jag believes she is wise to the possibilities and the dangers, but Jag is the heir of House Red Cap. Her father is Osmondo Red. Consequences have been, in her experience, things that happen to other goblins.

The other reason no one in the bar is willing to cure Jag of her assumptions is Sil. Sil stands behind Jag’s chair. Sil with a sword strapped to her back, and scars on her face that the sweep of her white-blonde hair cannot quite obscure. Half-goblin, half-sidhe, every angle on her body seems to have been sharpened to a point. And while her skin is too green for the tastes of the fae around her, too pale for the goblins back home, she is more than prepared to take on anyone who wants to take it up with her.

Sil

Sil hears the music. She sees the encounter with the numinous it inspires in Jag. She finds it does nothing for her. To her, the notes are simply obfuscation, hiding mutters, muting angry words.

What Sil does care about is intent. The way one gnome shifts his weight, the way another kobold stares. She cares about the purposeful movements that the fae try to dissemble. She cares about escape routes and high-priority targets.

She has the whole bar charted by now, the route of every wooden tray of spiked milk and moss-stuffed taco catalogued. She sees everything except the thing that makes Jag grin and look round at her, and say, “It’s so beautiful!”

She wonders if she ever did that. Ever turned and smiled and exclaimed in wonder. She can’t remember. When she looks back, her past is a mist she cannot penetrate. Only the lessons she was taught stand out. Islands of memory. Each beating distinct.

She nods, though. She has been taught to agree with her half-sister. Another lesson drummed into her ribs. Her kidneys. The back of her skull.

Jag turns back to the band, grinning. Sil checks to make sure that no one else has made a move. To make sure that Jag is safe.

In the end, that is all she does, and can, care about.

Knull

Deeper into the bar, away from the stage, and through the press of onlookers, Knull is shifting his weight from foot to foot. He is made restless by his father’s pixie blood, made anxious by his mother’s brownie heritage.

Every drug deal, Knull knows, is a fuck-up waiting to happen. It’s not that he’s a pessimist. It just that he knows the best-case scenario is that everyone goes home afterwards and makes themselves incrementally dumber.

Knull also knows that every drug deal is a chance to make serious cash. Especially when the shit he’s selling has been cut three ways to Mourn’s Day, and is likely to only get the purchaser about as high as a three-day-old balloon. And that’s exactly what he’s going to sell to the pair of dull-eyed gnomes in front of him now. They aren’t regulars. They aren’t locals. That means they get the tourist special.

“This?” Knull shakes his baggy of Dust at the pair. “You don’t want this.” He slips it back into his pocket. He points to the other baggies he’s spread out on the table.

“Titania’s Revenge.” He picks up a bag of completely identical Dust. “It’s like being kissed on your frontal lobes.” He picks up another—its contents in absolutely no way different from the previous two bags. “Iron Blood. It’s got a bite, but it’ll be one hell of a night.”

“Why,” says one of the two gnomes, “don’t we want the other bag?”

Knull pats his pocket. “This? Serious customers only, mate.”

The gnomes exchange a look. They are big, shirtsleeves rolled up to reveal tattoos and biceps. Knull recognizes their guild brands: coal miners. No Dust, he thinks, will ever get them as high as their own sense of self-importance.

“You think,” one gnome says, “that we ain’t serious?”

Knull pats his pocket one more time. “Midsommar Dreams? That’s dryads only, my friends. It’s not personal, just biology. This would screw you up so bad you wouldn’t know your own names for three days.”

The gnomes exchange a look.

“I want the Midsommar Dreams,” one says.

This, Knull thinks, is like taking sap from a dryad. Except it’s taking money from idiots, which is potentially a whole lot easier.

“I’m telling you, guys. It ain’t for sale.”

One produces a fistful of coins. “You sure?”

Then comes the pantomime of indecision. “Fine,” Knull says eventually, “but let me make sure you’re up for it first. My conscience and all.” He slips a finger into his pocket, into a baggie entirely dissimilar to the one that contains the so-called Midsommar Dreams, the one he’s been holding back in case one of his regulars shows up. He dips it directly into the pure shit.

He pulls out a white-tipped finger. “Here,” he says, tapping the residue off onto a tiny sheet of rolling paper. “Rub that on your gums and don’t tell me I didn’t warn you.”

Their eyes are as big as saucers. There is some shoving to get to the Dust first. The bigger one wins. His finger goes into the Dust, and then he works it around his mouth like he’s trying to unclog a drain.

His eyes balloon.

Knull has never seen the production of Dust, but he’s heard about it plenty. It is a tree resin, he has been told. The resin is ground down, and can be ingested in a variety of ways. Some like to snort it, others to eat it, while others like to heat it up and inject into the vein of their choosing. You can even smoke the stuff if you like.

Users of Dust like to tell Knull that the specific method of ingestion varies the high they get, but from Knull’s perspective the end result is always the same. For just a moment, for just that fae, the Iron Wall goes away. For just a moment, they touch the world that was, the world that went away. For just a moment, magic is alive within their hearts.

And then the magic goes away, and they come back, and they pay Knull so that they can do it all again.

So now, the gnome’s pupils dilate, and wind sweeps his hair. Knull watches a snake weave a crown upon the gnome’s forehead, and grass pushes up through the linoleum at his feet. Sunlight seems to reflect in his eyes.

And then it’s over, the moment gone. The snake slithers back into nothingness. The grass wilts and all that’s left beneath the gnome’s feet are cracked tiles and stale puddles. He gasps, staggers, and grins.

“Shit, yes,” he says.

The gnomes count out tin cogs. Knull tries to not salivate. He fishes the bag labelled “Midsommar Dreams” over. The gnomes high five each other, and then, when their backs are turned, Knull heads for the door as fast as he possibly can.

Jag

The band takes a break. Jag doesn’t. She gesticulates with her cigarette. She expounds upon a theme.

“This,” she says, “is real. Right here. Right now. That’s what fae music is about. It’s about the intersection of out there and in here.” She taps her sternum. “That’s the problem with goblin music, Bazzack. It’s all externally focused. It’s all indicative of a conqueror’s mindset.”

Bazzack—the target of this rant—is underwhelmed. He is the son of a minor colonel within House Red Cap’s ranks. A rich, young, bored goblin, whose rough edges money cannot fully erase. They have known each other forever, and she is far enough out of his league within their house’s hierarchy that she felt confident to bring him here without having to suffer through any painful flirtation. Still, platonic familiarity comes with its downsides.

“You do have a rough sense,” Bazzack says, “of how absurdly pretentious you sound right now, don’t you?”

And the thing is, Jag does. She knows what she is and where she is. She knows how both Bazzack and the fae see her sitting here. But she also knows that doesn’t stop her words from being true. It doesn’t stop her fellow goblins from needing to hear them. To hear them and realize that it’s not just posing, or an angle, or a new look for this season’s balls.

Bazzack, though, Jag is coming to see, is not the goblin who is going to make that realization.

“This,” Bazzack says, just to ensure his particular brand of boorish ennui gets its moment in the spotlight, “is poor fae music, in a poor fae bar, in a poor excuse for a neighborhood. And the brooding-artiste look may get your suitors to feign a little more sensitivity, but don’t pretend to be so naïve that you imagine that solicitude will last past the moment when they finally talk their way between your bedsheets.”

“That—” Jag leans forward. “—is exactly what I’m talking about. You’re seeing all this as a pose, as something put on for others to observe. You can’t for a moment picture this as something genuine, and that’s the whole—” She stabs with the cigarette. “—damn problem. Because this music isn’t anything about that. It’s about revealing the internal.”

She glances back at Sil. At her half-fae half-sister. Her father’s bastard daughter. She looks to see if any of this is getting through. To see if any of her sidhe mother’s heritage is being unlocked. “What do you think, Sil?” she asks.

Sil looks at her for half a second. “The music could be a useful cover in the opening moments of a fight, for whoever wishes to initiate it.”

Bazzack laughs. Jag gives Sil a pleading look.

“It may also serve to mask anyone approaching me from behind,” Sil says.

Bazzack laughs harder. Sil is entirely unfazed by his amusement. The only movement in her face comes from her eyes, which go back to dispassionately scanning the bar and its occupants.

“I don’t know why you bother with her,” Bazzack says. “Her blood is tainted with—” He raises his voice. “—fae bullshit.” The crowd studiously avoids reacting. Bazzack sneers. “You know your father doesn’t want you doing this. She is a servant. Nothing more.”

Jag shakes her head, reaches out, puts a hand on Sil’s arm. “She is my sister.” Sil doesn’t react in the slightest.

“She is the accidental result of your father indulging his urges.”

“How she came into this world is of no concern to me,” Jag says, keen to move on from the idea of her father in the moment of conception. “She is here nonetheless, and what is happening here is part of her culture and her heritage.”

It would be an easier argument to make if Sil was willing to give the impression she had any sort of emotional range beyond that of the pint glass on the table before Jag.

“You can dress this shit show and your indulgence of it,” Bazzack says, stifling a belch, “in any pretty words you want. But they are literally on stage, putting on a show. It’s all bullshit. Just—” another grin “—like you.”

Sil

She knows how she will do it if Jag asks her. Pirouette around the chair, stab her sword directly into Bazzack’s ballsack. Such a small target, she thinks, will at least make it something of a challenge.

Edwyll

The evening twists on. Deeper and darker. Glasses rise and fall. Spirits move along with them. It’s easy to be despondent in the Fae Districts. It’s easy to focus on the cloying air and the dirt-smeared walls, and think about what was here before the Iron Wall. It’s easy to think about what could be if the fae weren’t cut off from their magic.

Some, though, would rather call bullshit on such defeatist attitudes. Some think that there is still the potential for beauty left in the world, and that the sun still shines if only the fae would stop and lift their heads, and see it beyond the chimney smoke.

Edwyll is such a fae. Edwyll thinks he has a medium and a message. Edwyll is trying to channel his mentor, Lila, and create the beauty he wants to see in the world. He is trying to create something that will remind his fellow fae that life did not end fifty years ago.

He hunches over a table in the corner of the bar. He stabs and dabs with his paintbrush, trying to capture the feeling that rose within him as the band played, building counterpoints of orange and blue, shifting tones of yellow sliding into red. He tries to make the kobold-hair bristles move the way his body wanted to move as the beat bounced through him.

And yet still, despite his conviction, despite his brave face, despondency lurks.

The problem, as ever, is money. Because even if he is successful in his transformation of elation into a visual medium, who will pay for it? Who will put enough food on his table that he’ll still be alive next week to create the next painting?

Edwyll isn’t even meant to be in this bar. He’s meant to be running home to grab some materials for his next big project. He’s meant to be checking that his drug-addled parents haven’t puked themselves to death. But he saw a flyer in the window about bartenders being wanted and then the proprietor needed to deal with some crisis or other, and he’s been waiting for half an hour, and the band started to play, and the spirit moved within him.

But now he’s hungry again, and the art isn’t quite what he wanted, and the spirit is starting to get sluggish.

He sits back, looks up, surveys the bar, these fae he wants to lift up out of poverty, these fae he is too poor to uplift, and then he sees them. Brownies knocking back spiced nectar. Two green leaves sitting about the blue, brown, and red bodies of the fae… surely not.

He blinks. He tries to make sure.

Two goblins. Two goblins sitting in the crowd. Two goblins slumming it for the night.

Two potential patrons.

He looks down at what he has accomplished on the scrap of canvas he’s holding. And screw it. It’s good enough.

He’s up and on his feet, pushing through the crowd before he has a chance to second-guess himself. He’s standing in front of them before he’s had a chance to figure out what he’s actually going to say.

“Great music, right?”

No. Not that. That was not the thing to say.

Two pairs of startled yellow eyes turn to him. He swallows.

“It’s amazing what great art can do, right?” He taps his chest. “Uplift the heart. Uplift the spirit. Change the whole world one heart and mind at a time.” He flashes a smile.

Against all odds, the female goblin’s face actually lights up. In defiance of logic, she smiles.

Then the male grabs the painting out of Edwyll’s hand, and sneers at the paint he’s just smeared.

“Peasant art,” he slurs. “I thought you lot were meant to be good at this shit. I thought you were meant to be good for at least one thing.”

“Hey, asshole—” are perhaps not the best words to deal with this situation, but they are the first two out of Edwyll’s mouth.

The goblin stands, sending his chair flying backward.

“What did you call me?”

Edwyll knows very well what he called him. He just doesn’t know if he’s willing to repeat it.

Instead of repetition, though, escalation. Before Edwyll can open his mouth, a large brownie puts his hand on the goblin’s shoulder. There are no butterfly wings on this fae. He is heavy-set, slabs of muscle scarred with burns and painted with tattoos. An ore miner on his way to the night shift that most of his kind prefer. He has rolled up his sleeves. His wrists are the breadth of the goblin’s thighs.

“This is the wrong part of town, son,” the brownie says, “to say shit like that.”

The goblin pushes the hand away. “I,” he says, “am the only good thing to ever happen to this shitty little bar, and this shitty part of town. If I am here, then it is exactly where I am supposed to be. You, peasant, are the one out of place in my city.”

Edwyll closes his eyes. Because he has always wanted his art to move people. He has always wanted it to create change in the world. But this is not what he had in mind at all.

Jag

Jag stands. Jag sees the faces around her. Jag blanches.

“I’m sorry,” she says to the fae with his hand on Bazzack’s chest—a brownie, or a pixie, or some mix of the two, she can’t be sure. “You are entirely correct. My friend is an asshole. We’re leaving.”

The brownie looks at her and Bazzack with distaste. Jag puts her faith in Sil standing behind her, in the fact that there is something in Sil’s eyes that normally speaks straight to every fae’s brain and gives them a single warning.

Bazzack, though, has silenced enough higher cognitive functions that belligerence has become his default setting.

“We are not leaving,” he spits. “We came here to have fun, Jag. And I am bored.” He grins at the brownie. “Five cogs,” he says. “I’ll pay you five cogs if you’ll fight her!” He points at Sil.

No. No. That is not why Jag brought Sil here. That is the opposite of why.

“No fae with fighting spirit left in the Iron City?” Bazzack shouts. “What if I make the pot richer? What if I pay one lead gear to anyone here who can best this half-fae in combat?”

“Shut up,” Jag says.

But it’s far too late for that.

“Show me the coin,” the brownie gripping Bazzack’s shoulder says.

“Show me something worth paying for.”

The brownie leans in closer. “How about I just take all your coins.”

Uncertainty rattles the bars of Bazzack’s intoxication. “Jag?” he says.

Jag wants them to leave. But she also wants to see the smirk wiped off Bazzack’s face. She wants to punish him a little for ruining this night. “She’s not your bodyguard, Bazzack,” she says.

Bazzack swallows. His confidence is starting to slip like an ill-fitting jacket. Nervous fingers fish out his coin.

“Good lad,” the brownie says. He lets go of Bazzack’s shoulder, claps him on the back. “Now, I’ll kick this half-gobbo’s ass.” He nods at Sil. “Then I’ll kick yours.”

He looks up, levels a finger at Jag. “And then I’ll kick your friend’s.”

Sil

The brownie’s mistake is that he has made one threat too many. Two, Sil can accept. The last, though, is taboo.

So, she reaches for her sword, and then, with a flick of her wrist, she removes his hand.

2

Old Dogs. New Tricks

Granny Spregg

There is more to the Iron City than one small bar in one small corner of town. The Iron Wall encircles a microcosm. One that sprawls. That heaves. Cars clog its streets. Industry churns. Fae and goblins stumble through its avenues and boulevards. Theaters pump out morality plays performed by immoral actors. Street vendors hawk powdered dragon fangs to stockbrokers. Building styles shift like river currents. And at its septic heart, the great Houses rise.

Once they would have been fortresses. Once there would have been crenellations and monsters of yore curled in deep dark dungeons. Once upon a time, though, is a distant memory in the Iron City. These Houses are modern buildings. Their inhabitants are modern goblins. Their tastes run to neither cold stone nor dark tapestries. They prefer central heating, and high thread-count sheets, and their guards armed with something that can spit out more than one bolt every thirty seconds. This is the modern world, after all, with all its modern dangers and all its modern indulgences.

Granny Spregg would rather like it if the modern world would go fuck itself.

Granny Spregg is a creature of a world gone away. She is a gnarled fist of a goblin. She drags her leg behind her as she stomps down one of the many, many corridors that twist and turn through House Spriggan. Her cane clack-clacks on the tiles. It was a dryad’s arm once. She cut it free herself.

Granny Spregg looks back on the Iron War with fondness. She remembers when her hordes broke the fae army’s back. She remembers when Mab’s Kiss broke their spirit. She remembers Mab…

Old goblin, she curses herself, as she bustles down the corridor. Thinking old goblin thoughts. Getting lost in the past, when the present is so full of snares.

No one here dares call her Granny to her face. They all use the name behind her back. There is, she supposes, some accuracy to it, even if none of the brats her children have clogged the House’s lower floors with are legitimate.

She uses the name in her head. It keeps the anger fresh. Keeps her lip curled and her feet moving. They carry her along the corridor now, hobbling step after step. A victor’s riches surround her. Her spoils despoiled. Fae paintings defaced. Sacred white deer, their heads mounted on plaques. A sculpture built from broken wands.

There is more modern art as well. Creations that conform to her children’s tastes. Letting them have their own opinions, Granny Spregg thinks. That was my first mistake.

Thacker scurries in Granny Spregg’s wake. Thacker always scurries in her wake. Granny Spregg is unsure if he is capable of any other type of movement. She moves at a pace snails would mock, and yet Thacker is always hurrying to catch up with her.

“Are you sure this is wise, Madame?” he asks, which is the most Thacker thing to say that Granny Spregg can think of. He would probably check with her about each inhalation of breath if he knew she wouldn’t wear his balls as earrings if he did so.

“No,” she spits at him. “Which is why I’m doing it. Certainty is the first sign of idiocy.” She grimaces. “My children are always certain.”

Thacker is not an idiot. He is neurotic as a brownie, and an anxious thorn in her britches, but he is not an idiot. It is why she tolerates him. She likes certainty only in her lovers, not in those she keeps around for intelligent conversation.

“Perhaps we should…” Thacker starts, but Granny Spregg is unwilling to let him get to the word “reconsider.”

She wheels on him, brings the cane to bear on his throat, and he almost scuttles right into it. She advances on him, pushing him back to the wall.

“Tonight, Thacker,” she says. “I have tonight. That’s it. To take it all back. This house. My house. All the years of effort and this is it. Eight meager hours. The package is in the city. It is all in play. And I will not have you fuck it up for me. Do you understand, or must I sacrifice a pawn this early in the evening?”

Thacker swallows. He nods.

Granny Spregg hits him with the cane. “Yes, you understand, or yes, I must sacrifice you, you dullard?”

Thacker cowers. “I understand,” he says, whimpering. “I understand.”

She turns her back on him. She stomps down the corridor. She reaches the door. It has taken longer than she wanted it to. Everything does these days. The door is large, steel-mounted, and monitored. Granny Spregg raises a vein-knotted fist to knock.

“Well, then,” she says to Thacker, “here we go.”

Granny Spregg summons every ounce of imperious pride left to her and shoves past the private who answers the door. Beyond this spluttering barrier, House Spriggan Military Command thrums with quiet efficiency. Goblins mutter orders into microphones with practiced monotony relaying, confirming, and processing missives. House generals lean over monitors and dispatch runners. Sergeants push figurines around a scale model of the city.

Such is the business of protecting the House’s interests, of keeping a populace in check and thwarting the ambitions of their rivals. Such is the business she would reclaim.

Granny Spregg does not belong in this room. There is no efficiency left in her body. Eyes turn to look at her.

She points at one goblin in full regalia. Her knuckles are large as walnuts. “General Callart,” she says through her self-loathing, “I need a moment of your time and a division of your soldiers.”

General Callart, she knows, can be relied on to be professional. Her presence here is unorthodox these days, but he will always be a slave to the hierarchy of command, and even now, she still outranks him.

“Of course, Madame Spregg,” he says smoothly while the bustle of the room resumes. “If you could furnish me with the details, then—”

“Perhaps before that,” a voice cuts in, “you could furnish me with a ‘what the fuck?’”

Another goblin steps out from behind a pillar of monitors. He is draped in unearned medals, drowning in aiguillettes. He is Privett Spregg in all his glory and absurdity.

Granny Spregg’s heart sinks. Thacker lets out a sound that could generously be called a groan, or accurately called a whimper.

This, Granny Spregg knows, will now have to be done the hard way.

Skart

The Iron City, of course, is not just mansions and bars. It is also squalor and squats. It is also high-rise pillars of steel and glass. It is also shops and stalls. Indeed, the Iron City has almost as many facets as it has ways to take your money and leave you lying in a gutter.

The Iron City also has factories in abundance. They churn, and belch. These are the truest monsters of the modern world, smoke pouring from their mouths, their wealth hoarded far away from the fae they subjugate.

In such a place sits Skart. He is a kobold, skin colored as if by sunburn, red hair sprouting from him in wild abundance, his face folded and puggish. He is in his office, hunched over a desk and an ancient typewriter, the chiaroscuro of a bare lamp bulb rendering him a partially glimpsed figure of light and shadow. A clock chirps. He looks up. Finally, it is shift’s end, and he is anxious to leave.

Then: a sound at his door. A creak of hinges. A scuffing of feet. He looks up, and sees a face peeking around the doorframe. One last thing left to deal with.

It is Bertyl, one of the tailors. A pixie like most of her coworkers, the bright yellow of her hair and skin are fading to cream as the years encroach. Skart smiles at her. Everyone, he believes, has a purpose they can achieve if you give them an opportunity. Bertyl has been struggling to find her purpose, but Skart believes he has an opportunity to give her.

“How can I help you, Bertyl?” he asks.

She shuffles towards him, looks back at the door. “Hello, Mr Skart, sir,” she says.

Then she runs out of steam.

“You’re here late,” Skart prompts as amiably as he can.

“Yes, sir.” Bertyl looks at her feet.

Skart knows he has to play this carefully.

“While I always appreciate company, Bertyl,” he says, “is there anything specific you want?”

Skart is a fae with one of the rarest possessions in the Iron City—a sliver of authority. He is a shift leader within a garment factory. He is not even a sidhe, and his success over the old-school network of nepotism that still persists in the Iron City in and of itself suggests either profound skill or unnatural ruthlessness. Evidence supports the former. He is a kindly boss. He helps organize and coordinate the efforts of tailors and machinists. He sets schedules and hears petty woes. It is not a position of great stature, but it is one that allows Skart to make his workers’ lives minimally easier. Bertyl, for some reason, seems hesitant to give him that opportunity.

“Well, Mr Skart,” Bertyl says, not meeting his eye. “I mean, of late I think, perhaps, you’ve been pretty complimentary about some of my dresses. And it’s been long hours, see. And, well, I’ve been here twenty years now, and so, well…” And there she seems to run out of nerve. She pants slightly.

Skart smiles. “This is about pay, isn’t it, Bertyl?” he says.

She gulps. “I’m sorry, Mr Skart, sir, and I wouldn’t ask… It’s only that my husband, Hasp, you know? He’s laid up near two months now with his leg, and things are… well they’re a bit tight, Mr Skart, sir.”

Things are tight. The song of the Fae Districts. Bertyl’s husband was badly injured when he was buried under a half-dozen massive bolts of undyed cloth after a fraying clasp on a delivery truck gave way. Skart is well aware that Hasp has been unable to work for almost two months now. Once, Skart thinks, the story would have filled him with rage. But not tonight. Tonight he will finally do something to stop any more harm coming to the fae.

Just… not yet.

“I understand,” Skart says. Bertyl sighs audibly. “And you have worked hard. And you deserve more.”

She glances at his eyes, just for a moment. He smiles again.

“But for you to have more, Bertyl, someone else will have to have less. There’s not more money. You know that. The goblins always give me the same amount every month. So, I have to share it out. And I have to be fair. So, I ask you, Bertyl, who should I give less to?”

Bertyl swallows. It’s a question she can’t answer. Others could. Others come to Skart and expound on the subject for hours. But it is a cruel question to ask Bertyl, and he knows it. He feels bad. But on the other hand, he was lying when he was complimentary about her sewing.

“I’ll tell you what, Bertyl,” he says, ending her agony. “You go home. I’ll stay here and look at the spreadsheets. Maybe there’s a corner I can cut somewhere, save a few copper teeth here and there. Maybe I can slip them your way. I know how badly Hasp was hurt.”

“Oh! Mr Skart…” She almost detonates with gratitude.

“It’s no worry,” he says. And here he comes to the crux. “I’ll be here a few more hours anyway.”

She stares at him. He could ask anything of her now. Except, it turns out, to leave quickly. It takes ten more minutes of stumbling thank-yous for Bertyl to depart. But Skart’s alibi is established. If anyone comes asking for him, Bertyl will swear to her grave that he is here. Hopefully it won’t come to that, though. Hopefully, Skart thinks, that isn’t her purpose.

He sits for a moment longer, bracing himself. He rolls up his sleeve, looks at the black marks beneath the skin. He has lived longer than most, he reminds himself. He has made it this far. He can make it just a little further.

He takes a breath. Rolls the sleeve back down. Stands up. Lets himself feel the rest of it. The excitement. The hope. His hands are trembling, he notices. Perhaps, though, he shouldn’t be surprised.

After fifty years, Skart is going back to war.

Granny Spregg

“Privett,” Granny Spregg says.

“Mother,” he replies.

In all honesty, Granny Spregg cannot be entirely sure who Privett’s father is. She knows who she said it was at the time, but given his size and disposition, there is very much a chance that there is some House Troll blood in him.

“Is there something you need, Mother?” he asks. He sounds, she thinks, like a sanctimonious asshole. Probably because that’s exactly what he is. She should have hired better nannies.

“I believe General Callart has my request well in hand.” This is the dance they must do. Because House Spriggan is the House she made it to be. She made the rules, and now she must live with them. She just never imagined she would get so old; that the mistakes of the past would mount so high that she wouldn’t even be in charge of her own idiot son.

“I am taking a personal interest, Mother,” Privett says. He exposes his teeth in something that could be called but is not a smile.

Privett. The middle child. All the insecurities so transparent in him. Hiding away with the real soldiers so he can feel like less of an irrelevance. Meanwhile, it was his eldest sister who orchestrated the coup that dethroned her.

Still, he was an accomplice, and Granny Spregg does not forgive him. Not for an instant.

“I would not wish to tax you with even a simple request,” she says. “I know how overwhelmed you get.”

The advantage of motherhood, she thinks, is that it lets you know exactly which pressure points are most painful.

“I am more than capable of determining the merit of your request, Mother.” There is a little color in his cheeks now.

She looks to Callart, a question in her eyes. She lets Privett see exactly who she thinks is in charge here.

Callart doesn’t take the bait, but Privett, she knows, is blind to any answer Callart gives. He is only capable of seeing his authority questioned. So, as she knew he would, he steps before her. He froths.

“Our operations have evolved since your day, Mother. You probably wouldn’t understand the delicate tapestry. I know how the years weigh on you.”

Granny Spregg needs to get her blows in while she can. She smiles thinly. “At least your sisters’ barbs have some wit to them,” she says.

He hulks over her. And she has become so frail, she thinks, he could probably kill her with a single blow. He might.

But, “Out!” he barks instead. “Your request is denied, Mother. I cannot have you upsetting operations you have no hope of understanding.”

Operations, Granny Spregg is well aware, is a word Privett is using to make himself feel better about the day-to-day housekeeping duties that occupy most of House Spriggan’s military: guarding factories and warehouses, ensuring none of the other Houses are making threatening moves, making sure that the fae are keeping their heads down.

“If Callart was capable of explaining these… operations to you, I’m sure he could explain them to me.”

And Callart does smile at that. Just a flash, just for her. But she lets Privett see that she has seen it. A shared grin in Callart’s direction. A look of quiet triumph even as she is defeated.

“Out!” Privett is purple and quaking.

And of course she must leave. No matter what barbs she plants here, her authority is gone, lost along with her youth.

She turns, hobbles. “Sorry,” she says, as he fumes at her. “I don’t move as fast as I once did.”

Finally, the door slams behind her. Thacker, still beside her, is breathing hard. “Well,” he says, “it was always a long shot. Perhaps it’s better that it’s over so soon.”

Granny Spregg turns to look at him. “Over?” She smiles. “Oh no, Thacker. This is just the start.”

3

Enter the McGuffin

Knull

In the alley behind the bar, a fox digs through garbage, and rats chitter back and forth. Among such peers, Knull checks over his shoulder. Junkies twitch, he thinks, and dealers check over their shoulders. Still, at least his paranoia isn’t delusional. He needs to get out of here before the two gnomes take the Dust he sold them.

Though the sale has left him feeling flush with cash, it has almost cleaned out the final dregs of his supply. Plus, his regular clients will require more potent mixtures than the ones he’s holding if they are to remain regular. It is time to restock. It is time to visit Cotter.

Cotter lives over in The Bends, which is either a cab ride or a half-hour schlepp away. In the end the math is simple: sore feet cannot stop Knull from running away from this ass-end of the Iron City, a lack of funds can. Cabs cost money.

Money. In the Iron City, it always comes back to money. Here, the days are not measured by the ticks of clocks but by the clinks of coins. Knull is glad he is not half-dryad, trying to put away coins that will last the length of a tree’s slow trudge through life, because he has his eyes on riches that will buy him a more vertical sort of mobility than a cab offers.

“I’m not stopping,” he’d told his younger brother when he’d left home for good. “Not even the Guild Districts, that’s not good enough. Not for me.”

He’d looked at the accumulated tides of shit—papers, books, dirt, and trash washed up by his parents’ neglect, by the pressure of poverty, by despair, by too many days with too many missed meals, by his parents’ guilt over it all, and by their desperate need to escape. He’d looked at his brother.

“You should come too.”

His brother had curled his lips. “You’re selling selfish bullshit as well as Dust these days?”

Knull had wanted to keep his temper, but his brother always made it hard. “It’s not selfish when the only reason they’re incapable of caring for themselves is that they keep shoveling Dust into their veins.”

“You sell Dust!” His brother’s hands were up in the air. “Do you hear yourself? Do you understand how hypocritical you sound?”

For a moment, fists were balled, for a moment this was going to go the way these conversations always went. And Knull hadn’t wanted to leave like that.

“I’m going all the way, this time,” he’d said. “I’m going straight to Low Spires. Musthaven maybe. I’m going as high as any fae can go in this city. There’ll be me, and rich goblin kids slumming it, and there could be you too. I can bring you with me. We’ll watch them blow out their sinuses on Dust, and we’ll laugh at the blood. Life could be so good. Come on. We can do it. You and me. We’re strong enough.”

But Edwyll hadn’t been. And Knull had left him behind. He’d glimpsed Edwyll in the bar tonight, just for a moment. And they’d nodded at each other, but that was all.

Because I’m strong, he reminds himself. Because I can make a commitment to a cause. I can take the risks and survive the odds.

So, he goes deeper into the alley at the back of the bar, past a scrawled mural of the White Tree, half-obscured behind a red spray where a goblin patrol threw a can of paint at it, and he grabs a lead drainpipe, and he climbs up towards the rooftops and the stars.

Sil

Back in the bar, blood drips from the blade of Sil’s sword. Crimson beads are stark against silvery steel. The crowd is backing away as the aura of the iron alloy—free from its scabbard—starts to sting. The blade is still, not a quiver in it.

The same is not true of the brownie who is currently at fifty percent of his usual number of hands. He quivers, alright. He flails. He screams as the iron-inflicted wound continues to burn and sizzle. Blood sprays from his stump even as he clutches the wound. It bursts between his fingers. He points it like a pistol, hoses Bazzack down, then the staring crowd.

Sil knows the kobold drummer is going to react before he does. He lurches forward and finds her blade going through his neck. With only the slightest pressure she threads the needle between his second and third vertebrae. The only noise as he drops comes from his crackling flesh.

More red on her blade.

She checks Jag. Osmondo’s heir is still standing there. She is still staring. So many are still staring.

The front door is closest. She will take that path.

She grabs Jag by the arm.

“No,” Jag says. But she is speaking to a moment that’s already passed.

I want you to come with me to the Fae Districts, Jag had said. I want to show you something. Something of your mother’s people. She’d been smiling as she said it, but in Sil’s ear it had been a command. Had been a statement that Jag was heading into danger.

On the day Sil had first met her father, Osmondo had said, Keep my daughter alive or I shall visit upon you a thousand plagues of pain. He was not joking. He does not have a sense of humor.

And so Sil came. No matter that her handlers had told her to leave Jag alone that night. No matter that she had been given tasks to perform patrolling a perimeter gate. Osmondo’s old directive superseded their new ones.

So now, she pulls Jag by the arm. Jag comes with her toward the staring onlookers. Sil shoves her forward then, holding onto her wrist, spinning her like they are dancing at a ball. Jag crashes into the crowd like a goblin-sized morning star. Only Sil’s grip on her wrist keeps her upright.

Bazzack screams after them, but Jag was right—Sil is not his bodyguard.

She charts the progress of stools, fae, glasses. She leaps, dances over a tabletop, ducks below a beam. She slashes with her sword, drives open a bloody wedge. She grabs Jag’s hand once more, heaves. Jag stumbles into the gap Sil has opened.

A bottle is thrown. Sil catches it, brings it down on the next obstacle’s head, steps over his slumping form. She glances back. Jag is still alive. Osmondo is still obeyed.

Quickly and efficiently, Sil cuts an exit out of the bar.

Jag

Jag is a somnambulist in a waking nightmare. She stumbles and trips while fae are paraded before her, each one clutching a grizzlier wound than the one before. She can hear Sil grunting. She can hear the smack of a blade against meat.

Then she’s outside. Pigeons billow up into the sky. A glitching neon sign advertising sparrow-nest omelets and acorn coffee to the late-shift crowd. Somehow all that has happened to her is that her shirt is untucked, and her jacket needs to be straightened, while behind her there are screams and rage.

Sil has put her signature upon the bar.

“Bazzack!” she has just enough breath to say as Sil slams her into the side of their car.

Sil shakes her head. And Jag knows. No one ever gave Sil any orders about Bazzack. And Jag’s lost the opportunity to give new ones. Sil is in charge now.

Sil opens the car door. And somehow, even as the fuse on the bar’s violence burns down, and the detonation of bodies that will come chasing after them thrums, she still finds the time to offer Jag her seat with a bow.

Jag dives into leather and lingering cigar smoke. She slams the door shut behind her.