Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IMM Lifestyle Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

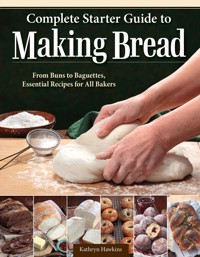

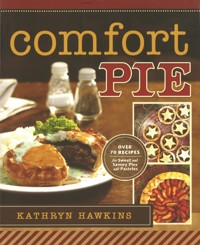

Pastry is one of the most comforting foods and is used the world over. In Comfort Pie, Kathryn Hawkins shares recipes for all the different types of pastry and for 70 glorious pies. There are large family pies as well as individual ones, pies for parties and pies for dessert. Easy step-by-step instructions make every pie within reach of the average home cook. The book includes recipes for sweet and savoury pies, and for pastries and tarts. From beef and onion 'clanger' to sausage and apple plait, and from ratatouille pie to plum and almond crostata, there is something for everyone. You'll love the Puff Pastry, Macaroni Cheese Pies, Just Peachy Filo Crisp, and Mini Pork and Chorizo Picnic Pies. Also included are dishes from all over the world, from American apple pie to French tarte aux pommes, and from Tunisian tuna bricks to delicate sweet pastries from the Middle East.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 187

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Introduction

A brief history of pies

The basics of pastry making

Types of pastry

Meat

Poultry

Fish

Vegetable

Sweet

Bibliography

Index

The idea for this book came from a conversation I had with myMum, so I’d like to dedicate the finished work to her and thank her for her inspiration.

Introduction

Pie is something I can remember eating and enjoying throughout my childhood. Minced meat, sausage or cheese and potato pies made inexpensive, tasty and filling suppers for our Mother to make us, and at the weekend, for a special treat we would have a homemade apple pie with custard or sometimes vanilla ice cream – we didn’t have a freezer, so we would wait in pie-eyed anticipation while Dad went off to the corner shop to buy an icy cardboard packed square of Cornish ice cream before we could tuck in. On every picnic, there was always a pie in some form or other – individual pork, sausage rolls or a wedge of egg and bacon pie were the most memorable.

When we went on holidays to stay with my grandparents in Devon, Grannie Watts would always produce a homegrown-fruit pie at some point – usually rhubarb or blackcurrant – served with luscious clotted cream. And always with homemade, short, buttery pastry – there were no short cuts in those days! – and a quirky blackbird pie funnel sticking out the top. Grannie’s sister-in-law Dorothy used to bake for the family café, and a visit to see her on the way to the beach meant that our picnic basket would be embellished with freshly baked, and still warm, savoury pasties. I do remember bad pie experiences just as well though: school dinner pies are certainly amongst the worst ones I have eaten. I can’t remember any savoury, just the pudding ones. The pastry was dry, hard and tasteless – mercifully only pastry on the bottom – and the filling or topping was either too sweet, paste-like and flavourless, or so sparse it looked like it had only been shown the pastry!

What is a pie? Well, I think a pie is different things to different people, so for the purposes of this book, I have kept to my own specific boundaries. First and most importantly, it must have pastry as the key ingredient – you’ll find no mashed potato tops or other pastry-less pies in this book. Secondly, the pastry should be baked to form a crisp crust or shell – so no steamed pastry. And, finally my pies have either a pastry top and bottom (or all round pastry casing), or are top crust only – this is typically British; if there is bottom crust (like an American pie) it must support a good hearty portion of filling and be topped in some way. Apart from that they can be any shape, size, in or out of a tin or dish, and made up with any type of pastry.

Pastry is a vital constituent of a really good pie, but the filling is of equal importance. While I have been writing my recipes, quite by chance, I was asked to be a judge on a panel for the Perthshire region of the Scottish Association of Meat Traders Steak Pie and Speciality Pie competition. I met some experienced pie making butchers who explained the techniques they used to get the right amount of filling in a dish but still achieve a good crisp puff pastry layer on top. We had a fine old time looking at the differing pastry textures and tasting the meat and gravy, and it was a very interesting, and extremely timely experience for me. On balance, it was the pastry that let most pies down, and then seasoning came in a close second.

I have tried to come up with pies for every occasion in the recipe section. To start with you’ll find recipes for different types of pastry if you fancy making your own - if you have sufficient time, I do recommend you try and have a go. There is something very satisfying about making your own pastry and the taste and texture of the baked result is far superior to anything readymade. However, time is of the essence, so I do state the quantity of pastry each recipe makes to enable you to substitute in a readymade version if you need to.

There are 70 glorious pie recipes to follow the basic pastries which are divided up into different chapters depending on the filling, and you’ll find recipes for large family pies as well as individual ones, using a variety of different types of pastry.

Before you start cooking though, you should read my tips and techniques on general pie and pastry making. Making a large meat filled pie is quite an investment on time and ingredients, so it seems a shame not to get a good result because of a simple problem in putting the pie together.

I hope you enjoy the book. I certainly had fun making all the pies and sharing them with friends and family, watching faces light up as I produced my latest pastry creation – pies are a very sociable food and everyone seems to appreciate a good one.

Happy pie making!

A brief history of pies

Pies are recognised and baked all over the world in many shapes, forms and sizes, but many languages offer no exact translation of the word; this leads food historians to believe that pies evolved in Europe, especially in northern regions. When I first came to write on the subject, every book I own on the subject of British food history is littered with references to pies dating back to Medieval times, but in other books of global culinary history they occur only as introduced dishes. In Larousse Gastronomique under the entry for “pie”, it reads: “The French have adopted the word for the classic British and American pies”. I like to deduce from my research, therefore, that the pie, is a very British dish, which we have shared with our cousins across the Atlantic Ocean! Pies are also popular in Australia and New Zealand.

Pies of old were primarily a means to cook, keep and transport an assortment of fillings – the tough, dough casing was never eaten. It is thought that the word pie (pâté in Medieval English) has an ornithological derivation and comes from magpie – a bird with the habit of collecting things. There are many historical references to pies of old throughout culinary history. As with many familiar things, pies can also be dated back to the Egyptians.

Humble pie dates back to Medieval times. Now a common saying, it evolved in households where the folk at the top of the pecking order would get the prime cuts, and the poor workers would get a pie full of entrails and offal – you’ll find my version of this recipe inside this book. Cornish tin miners used to carry a pastry with savoury mixture at one end and fruit or jam (jelly) at the other in a roughly honed dough which was discarded once the insides were eaten – this was the original Cornish pasty. It was during the times of the Tudors, that pastry, or paste as it was known then, really became part of the dish called “pie”. Eggs were added as well as cold fats like butter and suet, and a more refined wheat flour was used for baking. Standing pies, like our raised pies of today, sound truly magnificent – like pieces of art you could actually eat. Pastry animals, birds, leaves and foliage were embossed or stuck all over the outside – just like we do today with our (crude in comparison) pastry cutters, and the patterns on the outside often depicted the filling within. For banquets and feasts heraldic emblems, coats of arms and other family emblems were also used as edible decor.

Shortcrust pastry recipes were recorded as early as 1545, but it wasn’t for another 50 years or so that flakier recipes started to appear written down. I’ve often wondered how puff pastry was first discovered – did someone forget to add the fat to the dough and then try to incorporate it afterwards?

It has been recorded that flaky pastry was an Arabic invention of around 1500. At the same time the Turkish were making filo (phyllo meaning leaf) sheet pastries for savoury and sweet dishes, and their rule over parts of Eastern Europe meant that this pastry was adapted by the Hungarians and Austrians to make their strudels.

By the end of the sixteenth century, pastry was widely made and eaten all over the world. The first American pie recipes began to appear in the late eighteenth century where fat was rubbed into the flour for a fine texture and some rolled in to give a good flaky crust. American pies are most usually bottom-crust only, which the British often refer to as a tart. Rarely have pies gone out of fashion and with our renewed enthusiasm for baking, comfort food and getting back in the kitchen, we’re all cooking like never before and pies are everywhere!

The basics of pastry making

There is no real mystery to turning out a good pie, but there are a few basics that you need to understand before you get started. Even if you’re using readymade pastry, you’ll still get a better result if you follow the same guidelines. I don’t think you can rush a pie and expect it to look or taste good. A pie is a real labour of love, and whoever you’re serving it up to will love you all the more for taking the time to get it tasting and looking right. I think a pie is an impressive beast whatever the occasion, and it seems a shame to rush it and then have it not turn out to your best advantage. With this in mind, I’ve put together some tips and techniques as well as my basic “pie rules” and general information to help you achieve your perfect, homely and satisfying, deliciously perfect pie. Read on pie enthusiasts.

Pastry ingredients

1) FLOUR

Provides the main bulk and structure of any pastry. Wheat flour contains proteins which form gluten, and gluten helps the pastry firm up and crisp when baked. Plain or all purpose white wheat flour is the most commonly used for a standard shortcrust pastry, with the wholewheat (brown) version offering a healthier, more wholesome crust. Wheat flour with added raising agent (self raising flour) is used for a softer textured pastry like suet crust, but if you fancy experimenting, it can be used for shortcrust and will make a crumbly textured pastry which merges into the filling during baking and offers a less pronounced crust.

If you are wheat intolerant, you can use gluten free flours – I have included suggestions and recipes. Pastry made with a gluten free flour will have a different texture but can still provide a perfectly adequate casing for many different fillings. Remember to choose a flour that will combine well with filling flavours for example, some flours like gram (chickpea) have a beany, earthy flavour and are best suited to savoury fillings.

For pastries with layers and flakes (flaky, rough puff or puff) or when a more robust or free standing pastry case is required (hot water crust), a wheat flour with a higher protein content and thus more gluten, is often used. Choose strong plain (bread) or white bread flour for a firmer, crisper result. However, a bread flour with too high a protein content can make a tough pastry that shrinks. Standard plain (all purpose) flour can be used for these pastries too and the results will be slightly softer and flakier in texture; the type you choose is down personal experimentation and taste.

As with all pastry ingredients, make sure you use fresh flour for best results. Store flours in their bags, well sealed, in a cool dry place.

2) FAT

Fat determines the texture and flavour of a pastry. Butter, vegetable shortening and lard are the most commonly used, but vegetable oils can also be used. Weigh or measure fat carefully as too much can make the pastry greasy and short (difficult to handle), while not enough will make a hard, dry pastry. Usually lard and butter are used together for best results, the former gives a short, crisp texture while the latter adds flavour. You will see recipes using combinations or a single fat. Choosing a hard vegetable fat is down to personal taste and health preferences. Choose a fat with no (unsalted) or a low salt content so that you can control the seasoning of the pastry – see notes on salt below. Avoid low fat spreads or any fat with an added water content (“spreadable”) as they will alter the texture of the finished pastry.

Shredded beef or vegetable suet is used for suet crust pastries. It’s down to personal taste which you prefer to use; personally, I prefer beef suet with savoury and vegetable suet with sweet fillings or delicate flavours like vegetables, fish and poultry.

If you want to experiment with different oils, make sure you choose an oil that is suitable for cooking. Delicate flavoured oils such as extra virgin olive or nut oils are not heat resistant – they are used to flavour a finished dish rather than cook with. However, when blended with a more robust oil like sunflower, they can be used for flavouring purposes. Remember that the colour and flavour of an oil will affect the final taste of the pie, so it is worth choosing a blander flavoured vegetable oil if you don’t want the pastry to dominate the pie filling.

Try to get the fat at the right temperature before blending with your flour. Rock hard fat, straight from the fridge, is too difficult to blend, but if it is too soft, the fat has already started to melt and won’t combine with the flour correctly. Don’t be tempted to blast fat in the microwave in order to soften it in a hurry; more than likely, it will get too soft and will ruin the pastry. Ideally, take the fat out of the fridge about 30 mins before using to make sure the fat is firm and cool, not soft and oily.

3) LIQUIDS

Water is the most commonly used liquid in pastry making and acts as a binding agent bringing the flour and fat together to make a dough. In general, 1 tsp cold water is used per 25g (1oz) flour for a short pastry, and 1 Tbsp water per 25g (1oz) flour for suet or flaky pastries. Sometimes milk, cream or yogurt is used instead of water to give a richer, shorter, more flavoursome pastry crust. Fruit juice can be used in sweet pastries to give more flavour – usually citrus juices are used with finely grated rind for increased zestiness.

Liquid is always added cold to a pastry with the exception of hot water crust, where it is heated with the fat until melted and very hot. Where egg is added (see following notes) the liquid content is reduced.

4) EGG

Usually only the yolk is added to pastry dough to enrich it in flavour, texture and colour. The extra liquid provided by adding the yolk to the mixture means that you will need to reduce the quantity of liquid you add in order to avoid an over-wet dough. Well-beaten whole egg is widely used in pastry making and brushed on raw pastry as a glaze. Beaten egg white and a sprinkling of sugar gives a crisp coating to a sweet pie, whereas egg yolk on its own gives an ultra-rich finish.

5) SALT

Adding this everyday condiment will help bring out the flavour of your savoury and your sweet pastries. Measure salt correctly, especially when adding to a pastry being used for a sweet filling –follow the guidelines stated in the recipe. Season the filling carefully too, keeping in mind that your pastry already has a salt content.

6) SUGAR

Sugar is added in small amounts to sweet pastries. White, fine, caster (superfine) or icing (confectioner’s) sugars are most commonly used as these are most easily blended in a pastry dough, but soft light brown and dark sugars can be used for a more rustic pastry, and will also give a more caramelised flavour and colour to a baked pie crust – definitely worth experimenting with. Sweet pies are also often sprinkled with sugar to give a crust either before baking or just before serving. Demerara sugar gives an added crunchy finish to a pastry crust before baking.

7) OTHER INGREDIENTS

To give a standard recipe a “twist” you can add small amounts of seasonings and flavourings to your mixture. Chopped fresh herbs, dried herbs or spices can be used successfully in a savoury pastry, and cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg and ground mixed spice are great with fruit fillings, as are finely grated citrus zests. Cocoa powder can be substituted in to a recipe instead of some of the flour content to give a chocolate flavoured pastry – add some sugar as well to reduce the bitterness. Liquid extracts or essences like vanilla, almond or coffee can be used for flavour – add these before adding any other liquid to avoid making the pastry too wet. Ground nuts and small whole seeds can be used in addition to or instead of some of the flour for flavour and texture, or for reasons of intolerance to wheat.

The rules for pastry making

• The most important factor in pastry making is temperature. For all the pastries covered in this book, except hot water crust, you need to keep everything cool. Don’t handle pastry more than you have to and use only your finger tips to rub the fat into the flour – if you suffer with poor circulation like me you’ll have cold hands which is regarded as a positive when it comes to pastry making! Rich short pastries and flaky pastries will benefit from resting in a cool place or the fridge before rolling and shaping again to firm up the fat content.

• If you prefer a short cut to rubbing in by hand, you can use a hand held mixer or food processor. It is always best to work the fat into the flour in short bursts, and the same with adding liquid, otherwise there is a possibility that the pastry can become too over-mixed or processed and will be tough as a result. Refer to the manufacturer’s instruction booklet for the correct settings and attachments.

• Add liquid in gradual, small amounts to avoid making the pastry dough too wet – if the mixture is too sticky it will not only be difficult to handle, it will dry out and harden too much on cooking. Avoid adding extra flour when rolling out if your pastry is too sticky as this will alter the proportion of ingredients and have a detrimental effect on the texture of the pastry by toughening the texture.

• Roll pastry in one direction. The easiest way is to roll it away from you - then turn and roll it in the same “away from you” direction. For rounds of pastry, form the pastry into a ball first, then rotate as you roll, pinching together any cracks that appear on the edge. Being methodical with your turning and rolling technique means you are building a good, even structure to your pastry, particularly important for flaky pastry making when the rolling process helps form the flaky layers for the finished pastry. Use as little flour as possible to avoid drying out your pastry, and keep rolling to a minimum to avoid over-handling. Admittedly, some pastries are more difficult to handle. For example those with a high fat content or low or no gluten. In this instance, you are better to try and loosen the pastry with a long, broad palette knife after every rolling, and either slide the pastry round on the work top, or if this is too difficult, roll in a methodical fashion up and down and then side to side, to achieve an even thickness.

• Most recipes in this book require you to roll out the pastry thinly. This means to a thickness of around 3-5mm (¼inch).

• Take care not to stretch the pastry to fit the tin or mould as this will mean that the pastry will shrink back during cooking and may become misshapen.

• Most recipes call for freshly made or shaped pastry to be rested or chilled before filling or baking. Always cover the pastry in clear wrap or if in a block, wrap in greaseproof paper. This will prevent a skin or crust forming, and will stop the pastry drying out or picking up other flavours.

• Pastry is best cooked in a hot oven so that the fat doesn’t “melt out” of the mixture but instead coats the flour particles quickly enabling the dough to cook to a crisp. Everyone’s oven heats up differently so if you are concerned that your oven may not be heating up correctly, it is worth putting an oven thermometer on the centre shelf of the oven in order to double check the temperature. This is the best way to ensure you are cooking at the correct temperature.

• Short and flaky pastries can be stored for 2-5 days in the fridge if you don’t want to use them immediately. You should wrap them well to avoid picking up flavours from other ingredients and to prevent a skin or crust forming on the outside. Similarly, these pastries freeze well. Wrap tightly and freeze for up to 6 months, then allow to defrost, still in the wrappings, in the fridge for a few hours until ready to use. Hot water crust pastry must be used while warm and fresh otherwise it will be too hard to handle. Allow a pastry to “warm up” slightly if it has been stored in the fridge – let it stand at room temperature for about 20 mins before using.

A word on readymade pastries

Some pastries are simply too time consuming to make and sometimes there just aren’t enough hours in the day to make your own pastry, so for those occasions we turn to readymade pastries. Shortcrust wheat flour pastry is available in fresh and frozen forms, for sweet and savoury baking, in different flavours, and in block or ready rolled sheets. While this is my least favourite of the “readymades” (I’m not too keen on the flavour) it is a perfectly adequate compromise to making fresh. You do have to follow the guidelines on the packet though regarding using and resting times otherwise the pastry shrinks.