Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Fox Chapel Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

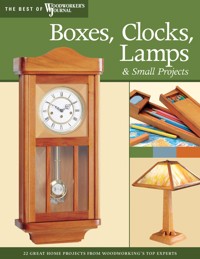

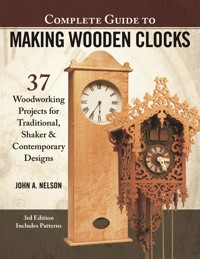

This complete guide to wooden clock making shows how to construct a wide variety of traditional, Shaker and contemporary clocks. Plans, parts lists, and instructions are provided for 37 handsome hand-made timepieces, including stately grandfather clocks, classic mantel clocks, and modern desk clocks. Author and clock collector John A. Nelson describes the history of clock making in America, and covers all the basics of clock making and clock components. An expanded step-by-step scroll saw project shows how to build an exact replica of a Shaker coffin-style clock. The rest of the projects include color photographs of the finished clock, measured drawings, and cut lists. Each clock plan includes front, right side and top views. All drawings are fully dimensioned and, where necessary, section views are provided. This new third edition of Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks also includes a bonus pattern pack with project templates.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 113

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

© 2000, 2003, 2018 by John A. Nelson and Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc., 903 Square Street, Mount Joy, PA 17552.

Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks, 3rd Edition (2018) is a revised edition of The Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks, 2nd Edition (2003), published by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc. Revisions include the addition of full-size pattern sheets. The patterns contained herein are copyrighted by the author. Readers may make copies of these patterns for personal use. The patterns themselves, however, are not to be duplicated for resale or distribution under any circumstances. Any such copying is a violation of copyright law.

Interior Photography: Carl Shuman, Deborah Porter-Hayes

Print ISBN 978-1-56523-957-9eISBN 978-1-60765-536-7

For a printable PDF of the patterns used in this book, please contact Fox Chapel Publishing at [email protected], stating the ISBN and title of the book in the subject line.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Nelson, John A., 1935-

Title: Complete guide to making wooden clocks / John A. Nelson.

Description: 3rd edition. | Mount Joy : Fox Chapel Publishing, [2018] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018008127 (print) | LCCN 2018009525 (ebook) | ISBN 9781607655367 (e-book) | ISBN 9781607655367 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Clock and watch making--Amateurs’ manuals. | Woodwork--Amateurs’ manuals.

Classification: LCC TS545 (ebook) | LCC TS545.N45 2018 (print) | DDC 681.1/13--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018008127

To learn more about the other great books from Fox Chapel Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free 800-457-9112 or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

We are always looking for talented authors. To submit an idea, please send a brief inquiry to [email protected].

Acknowledgments

Producing a comprehensive book like this requires many dedicated people. I could not have done it alone. I would like to thank the following people for their help and input: Joyce, who spent hours and hours on the computer typing, struggled with my poor penmanship, and put it all into a readable manuscript; Wesley and Alice Demarest of Sussex, New Jersey, for doing such an excellent job making all the clocks in this book—their woodworking skills are superior; and Debbie Porter-Hayes of Hancock, New Hampshire, for taking many of the wonderful photographs used in this book. To Alan Giagnocavo of Fox Chapel Publishing Company of Mount Joy, Pennsylvania, and his very dedicated staff: I want each of you to know how much I appreciate all your efforts. Your help and support really made this book. I hope you like all our efforts!

John A. Nelson

John with the original Eli Terry Pillar and Scroll Clock.

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1:A Brief History of Clocks

CHAPTER 2:America’s Popular Clocks

CHAPTER 3:Clock Components

CHAPTER 4:Making Your Own Clock

CHAPTER 5:Making a Coffin Clock

CHAPTER 6:Plans for 37 Clock Projects

Cat Lover’s Wall Clock

Woodland Fawn Clock

Super-Simple Desk Clock

Angel Desk Clock

Business Man’s Clock

Eight-Sided Classic Clock

Roman Corners Clock

Trophy Buck Wall Clock

Writer’s Desk Clock

Pyramid Desk Clock

Sextant Desk Clock

Balloon Shelf Clock

In-the-Balance Shelf Clock

Three-Wood Pendulum Clock

Mission Easel Clock

Tambour Shelf Clock

Petite Shelf Clock

19th-Century Shelf Clock

Lion’s Head Black Mantel Clock

Kitchen Clock with Drawer

Mission-Style Mantel Clock

Early Mission Shelf Clock

Skeleton Shelf Clock

See-Thru Wall Clock

New England Wall Clock

Simple Schoolhouse Clock

Country Pantry Clock

Collector’s Shelf Clock

Modern Long-Case Clock

Krazy Klock

Onyx Office Clock

Clergyman’s Wall Clock

Shaker-Style Coffin Clock

Fancy Cuckoo Clock

1840 Shaker Wall Clock

Vienna Clock

1802 Grandfather Clock

APPENDIX A:

Clock Museums & Antique Shops

APPENDIX B:

Clock Project Wood

Introduction

In years past, time passed with little or no urgency. Owning a clock was an indication of prosperity rather than a commitment to punctuality.

The passing of time has always been recognized by man, and man always had a fascination with trying to measure and record that passing. At first, it was the passing of days, the waxing and waning of the moon, and the changing of the various seasons. Time was very important in early days so that people could keep track of when to plant and harvest. The actual hour and minute of the day was not particularly important.

Early sundials were invented to keep a rough track of the passing of the hours. Other simple devices such as the hourglass, indexed candles that burned at a fixed rate and water power followed. Years later, the first mechanical clocks appeared. Today clocks of all shapes and sizes help us track time right down to the millisecond.

This book is written to appeal to anyone who likes and appreciates clocks. Various kinds of clocks and designs are included to reach all woodworking levels and all interests. I am sure there is something here for everyone. I included a little history about clocks, an introduction to the latest clock parts and accessories available today, and instructions on how to make use of them and where to get them. Noted, also, is information on the National Clock and Watch Association and a few of my favorite museums located throughout the country.

I sincerely hope you will enjoy this book and that it will get you started on a clock project of your own.

In early days, town folks relied on the church or town hall clock. Owning a clock was an indication of prosperity rather than a commitment to punctuality.

CHAPTER 1

A Brief History of Clocks

The theory behind time-keeping can be traced back to the astronomer Galileo. In 1580, Galileo, who is well-known for his theories on the universe, observed a swinging lamp suspended from a cathedral ceiling by a long chain. As he studied the swinging lamp, he discovered that each swing was equal and had a natural rate of motion. Later he found this rate of motion depended upon the length of the chain. For years he thought of this, and in 1640, he designed a clock mechanism incorporating the swing of a pendulum. Unfortunately, he died before actually building his new clock design.

In 1656, Christiaan Huygens incorporated a pendulum into a clock mechanism. He found that the new clock kept excellent time. He regulated the speed of the movement, as it is done today, by moving the pendulum bob up or down: up to “speed-up” the clock and down to “slow-down" the clock.

Christiaan’s invention was the boon that set man on his quest to track time with mechanical instruments.

EARLYMECHANICALCLOCKS

Early mechanical clocks, probably developed by monks from central Europe in the last half of the thirteen century, did not have pendulums. Neither did they have dials or hands. They told time only by striking a bell on the hour. These early clocks were very large and were made of heavy iron frames and gears forged by local blacksmiths. Most were placed in church belfries to make use of existing church bells.

Small domestic clocks with faces and dials started to appear by the first half of the fifteenth century. By 1630, a weight-driven lantern clock became popular in the homes of the very wealthy. These early clocks were made by local gunsmiths or locksmiths. Clocks became more accurate when the pendulum was added in 1656.

Early clock movements were mounted high above the floor on shelves because they required long pendulums and large cast-iron descending weights. These clocks were nothing more than simple mechanical works with a face and hands and were called “wags-on-the-wall.” Long-case clocks, or tall-case clocks, actually evolved from the early wags-on-the-wall clocks. They were nothing more than wooden cases added to hide the unsightly weights and cast-iron pendulums.

JOHNHARRISON(1693–1776)

Little is known about this man, the one person who, I think, did the most for clock-making. John was an English clockmaker, a mechanical genius, who devoted his life to clock-making. He accomplished what Isaac Newton, known for his theories on gravity, said was impossible.

John Harrison was born March 24, 1693, in the English county of Yorkshire. John learned woodworking from his father, but taught himself how to build a clock. He made his first clock in 1713 at the age of 19. It was made almost entirely of wood with oak wheels (gears). In 1722 he constructed a tower clock for Brocklesby Park. That clock has been running continuously for over 270 years.

One year later, on July 8, 1714, England offered £20,000 (approximately 12 million dollars) to anyone whose method proved successful in measuring longitude. Such a device was desperately needed by navigators of sailing vessels. Sailors during this time were literally lost at sea as soon as they lost sight of land. One man, John Harrison, felt longitude could be measured with a clock.

John Harrison

During the summer of 1730, John started work on a clock that would keep precise time at sea—something no one had yet been able to do with a clock. In five years he had his first model, H-1. It weighted 75 pounds and was four feet tall, four feet wide and four feet long. To prove his theory, John built H-2, H-3 and H-4.

His method of locating longitude by time was finally accepted and he won the prize. It took him over 40 years. Today, his perfect timekeeper is known as a chronometer.

CLOCKSINTHECOLONIES

In the early 1600s, clocks were brought to the colonies by wealthy colonists. Clocks were found only in the finest of homes. Most people of that time had to rely on the church clock on the town common for the time of day.

Most early clockmakers were not skilled in woodworking, so they turned to woodworkers to make the cases for them. These early woodworkers employed the same techniques used on furniture of the day. In 1683, immigrant William Davis claimed to be a “complete” clockmaker. He is considered to be the first clockmaker in the new colony.

Great horological artisans immigrated to the New World by 1799. Most of these early artisans settled in populous centers such as Boston, Philadelphia, New York, Charleston, Baltimore and New Haven.

Clock-making grew in all areas of the eastern part of the colonies. The earliest and most famous clockmakers from Philadelphia were Samuel Bispam, Abel Cottey and Peter Stretch. The most famous clockmaker was Philadelphia’s David Rittenhouse. David succeeded Benjamin Franklin as president of the American Philosophical Society and later became Director of the United States Mint.

Most Early American clocks had wooden gears, as brass was very expensive and hard to obtain.

NINETEENTHCENTURYGRANDFATHERCLOCKS

Inexpensive tall-case clocks were made in quantity and became more affordable after 1800. The clock-making industry spread to the northeastern states. In Massachusetts, Benjamin and Ephram Willard became famous for their exceptionally beautiful long-case clocks. In Connecticut, mass-produced long-case clocks were developed by Eli Terry.

In early days, almost all clock cases were made by local cabinetmakers. A firm that specialized in clock works fashioned the wood or bronze works. Cabinetmakers engraved or painted their names on the dial faces, thereby taking claim for the completed clocks.

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, regular factory working hours and the introduction of train schedules, standardized timekeeping became a necessity. Clock-making moved to the forefront.

Wooden movements were abandoned in 1840 and 30-hour brass movements became popular. They were easy to make and inexpensive. Spring-powered movements were developed soon after. A variety of totally new and smaller clock cases appeared on the market.

NINETEENTH-CENTURYMANUFACTURERS

Clock manufacturers were mostly individual clockmakers of family-owned companies. After 1840 however, Chauncy Jerome built the largest clock factory in the United States. He started shipping clocks all over the world. The Jerome Clock Company motivated the organization of the Ansonia Clock Company and the Waterbury Clock Company. These three companies, along with Seth Thomas Company, the E. N. Welch Company, the Ingraham Clock Company, and the Gilbert Clock Company, became the major producers of clocks in the nineteenth century. There were over 30 clock factories in this country by 1851. From 1840 up to 1890, millions of clocks were produced in this country, but unfortunately, very few still exist intact today.

Elias Ingraham

Elias was born in 1805 in Marlborough, Connecticut. He served a 5-year apprenticeship in cabinetmaking in the early 1820s. By 1828, at the age of 23, Elias was designing and building clock cases for George Mitchell. When he was 25 years old, he worked for the Chauncey and Lawson Ives Clock Company, which was still designing and building clock cases.

Elias formed a new company with his brother Andrew in 1852 called the E. and A. Ingraham and Company, but 4 years later, it went bankrupt. A year later he formed his own company with his son, Edward. Changing the name to E. Ingraham and Company, the business began manufacturing clock cases. By 1862, his then successful company manufactured its own movements, as well.

Throughout his lifetime, Elias was granted many clock case design patents. He died in 1885, but the company he started continued. Elias was perhaps the greatest clock case designer ever, and his clock designs are still being copied and produced today.

Marshall and Adams Clock Factory, Seneca Falls, New York, circa 1856.