Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

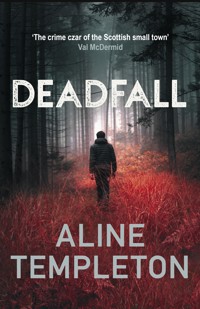

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: DI Kelso Strang

- Sprache: Englisch

Drumdalloch Woods near Inverness is a sinister place of tangled growth and shadowy darkness. It has business opportunists, biological scientists and conflicted family members all competing for a say in its future. Then a body is found, and everything starts to look suspicious. DCI Kelso Strang's investigation unearths layers of hatred, greed and revenge that cast doubt even on the local police force. Having only just found happiness with his new girlfriend, Cat Fleming, Strang faces an existential threat not only to his career but to his very life..

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 503

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

2

3

DEADFALL

ALINE TEMPLETON

4

5

For Clare Robertson, my most dedicated publicist, with much love.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

2020

The first streaks of dawn were no more than a narrow band on the eastern horizon that highlighted the gnarly roots and rough grasses, then slowly widened as it crept up over bark and branches to gild the lowest leaves with early April sunshine.

In the darkness of the trees and bushes the birds were waking with little mutterings and stirrings until the blackbird’s clear whistle, as imperious as the tap of a conductor’s baton, signalled the start of the chorus. Then all around responses began – somewhere the croon of a woodpigeon, the aggressive shouting of a wren, then more twittering and cheepings as the light grew.

It was cold still, with patches of ground frost in the shade and even in the open spaces the dew glittering on the grass was icy cold.

But Lachie MacIver was used to that, and to rising early; he was getting old now and his mattress, worn thin 8with use, pained him so that he was glad enough to rise at first light. He lived in the shepherd’s bothy on the edge of the estate; they’d sold off land after the old lady died and there hadn’t been sheep for forty years, but when they’d no further use for him they hadn’t turfed him out. They’d just let it decay, and now there were cracks in the walls and rain could find its way under the rusted corrugated-iron roof that lifted a little in a high wind.

Do-gooders he despised had tried to move him out, but his answer had been short and to the point. Very short. Here he was his own man, walking the five miles to the village for his pension and supplies and other times living off the land, as he called it.

There was a pheasant shoot across the valley and they were early risers too, and easy pickings. The sun was up by the time he set off, the shotgun broken over his arm – his father’s old gun the polis didn’t know he had. Plenty folk did know, but round here they wouldn’t clype.

He set off to take the short-cut through Drumdalloch Woods. They got nasty if they caught him doing that; he wasn’t above taking a fat pigeon if there was no one around – they were daft about birds. By now he’d need to be careful; there were youngsters who’d nothing better to do than checking on wee machine-things they’d set up and writing stuff down.

Lachie paused, listening, as he reached the trees. Even in his heavy boots he could move silently but he’d hear them coming – clumsy, snapping twigs and swearing when they tripped on something. This morning there was only the racket the birds were making and beneath their songs he could feel the deep silence of the woods. 9

It had a curious power and it was tempting just to stand, losing himself in it, but he needed to get on. He headed for the glade near the middle, crossed by a track leading to Drumdalloch House, the backbone for multiple branching tracks and the route anyone doing the early morning checking would take. He was ready to walk quickly across when something caught his eye.

A huge oak, an ancient giant, stood at the far end and someone was lying across its gnarled roots. He stepped back out of sight. They often made their daft checks from funny positions and there was a rough wooden nesting platform above, right enough, but it had fallen off and the way the person was lying didn’t look right.

When he got nearer he caught his breath. It was a woman, and he recognised her – Perry Forsyth’s wife. Wearing jeans and a padded jacket, she was lying on her back against the oak with one foot twisted under her, like she’d maybe reached up to the platform and pulled it down on top of her. It looked like it had missed her, but then she must have tripped as she ducked out the way.

This was a right mess. She wasn’t moving and he could see a bloody wound on her head. Must have given it a right good bash against the root. Maybe she needed help – but he shouldn’t be here, and if he stayed they’d maybe say he’d done something to her.

With an anxious look around, he went to check – not too close, being careful to tread on firm ground. And even from there he could tell she was dead.

The open eyes, glazed, the jaw starting to sag, the little trickle of blood running out of one ear – oh yes. An old soldier, he’d seen enough death before, in battlefields he 10still revisited on one of his bad nights.

This would be hard on her bairn, but there was nothing Lachie could do for her. Someone would find her soon enough. With another nervous glance he retreated, disappearing into the trees. The pheasants were safe for now and later he’d walk to the village to pick up any news.

He’d like to be sure they’d found her. He wouldn’t want to be left like that himself; the flies would find her first and soon other woodland creatures would be running or crawling or more horribly squirming here to perform their interconnected tasks as undertakers.

The white-faced student, who had been doing a check on the data loggers on the trees chosen for the current study, had come stumbling into the kitchen at Drumdalloch House, tear-stained and so shaken she could hardly get the bad news out.

As if he hadn’t taken it in, Giles Forsyth stood still as a statue; only the furrow between his heavy grey brows deepened. Beside him his daughter Oriole gasped, almost dropping her coffee mug, and her other hand went to her throat.

‘Helena – dead? Are you sure? Where is she?’

‘I’ll show you. Yes, it’s – well, sort of obvious.’ Her voice broke. ‘Fell and hit her head badly, I think. There’s great tits nesting in the box above – she probably went to make a recording and overbalanced.’

Giles cleared his throat. His voice was perfectly level as he said, ‘You go with her, Oriole. I’ll phone the police.’ His daughter nodded and went out, her arm around the girl who was still trembling visibly. 11

He didn’t move for a few moments after they left. He wasn’t sure he could. A man of his generation, he gave no outward sign of the inner maelstrom of grief, helpless rage at fate and the bitterness of blighted hope. His daughter-in-law, lovely Helena, who had wholeheartedly shared the plan his own children were determined to thwart, was gone, and those children would destroy all he believed to be important the day he was safely dead himself.

His grandmother had dinned into him that these woods were a sacred trust, to be left to him, bypassing his older brother because he’d shared her passion for the glory and majesty of the ancient trees, sanctuary for generations of woodland birds, with records going back more than a hundred years. He’d tried to pass that on to his children but he’d failed. Oh, Oriole paid lip-service but she’d never be able to stand against Perry. The historic legacy meant nothing to him.

He’d called his children Peregrine and Oriole; Perry had always mocked the sentimentality and had raged when Helena had encouraged the son named James to call himself Jay.

Dear God, Jay! A mother’s boy, undoubtedly; what would it do to him to lose her, aged ten? Giles would do his poor best for him, but the scar would be deep and disfiguring – and Jay would be all Perry’s child, ready to be shaped and no longer a pledge for the future of the woods.

He was old and tired, not fit for the struggle. Perhaps he could train himself not to care what would happen when he wasn’t there to see it, but his mental torment felt like physical pain, deep inside him. They said you could die of a broken heart. Perhaps you could. 12

He straightened his shoulders and walked stiffly over to the phone. ‘Giles Forsyth, Drumdalloch House, Kilbain … Fatal accident,’ he said.

Apart from going into the village where he’d learnt she’d been found all right, Lachie stuck close to the bothy. He could hear activity in the woods and catch sight of folk moving around, but he wasn’t going to get caught up. The polis asking questions would mean trouble.

Next morning he took the ferret from her cage, a pretty jill with a brown bandit mask across a silvery face, petting her briefly before she nestled down in his pocket in patient expectation.

He collected the purse nets and the wooden pegs he’d whittled himself, then, a spade over his shoulder, set out for the south-facing slope at the end of the field, honeycombed with rabbit holes. There were no rabbits visible; dawn feeders, rabbits, and if he’d wanted to shoot one he’d have been out at first light. Now, though, they’d be asleep with full stomachs.

There was a small burrow he and the ferret both knew, one that past experience had shown had fewer escape tunnels than the larger ones. Moving quietly, he stretched the net across a tunnel opening and had just started on the pegs when he realised someone was coming up behind him, quiet on the soft grass.

Lachie turned. Jay Forsyth’s face was blotchy and his eyes were swollen, but he wasn’t crying and Lachie said only, ‘Never heard you coming. Make a poacher of you yet.’

The answering smile was fleeting. The boy said abruptly, ‘Can I stroke Jill?’ 13

‘If Jill wants to be stroked.’ You didn’t take liberties with ferrets, who tended to make their feelings known in a very direct way, involving razor-sharp teeth and a lot of blood.

But she had poked her head out of the pocket already, inquisitive and bright-eyed. Her whiskers quivered as Jay held out his hand for her to sniff.

‘Want to come?’ he said softly. Recognising a friend, she came to him and settled as he cradled her, stroking the soft fur.

Lachie watched them silently. After a few minutes Jay, not looking at him, said, ‘Have you heard what happened to my mum?’

‘Heard she’d an accident,’ he said gruffly.

‘Yes, that’s what they said. She’s dead. Did you know?’

‘Aye, I heard that too. That’s bad.’

He was holding the ferret more tightly and Lachie took a step closer, ready to move in if necessary, as Jay said, ‘But do you know what I heard her saying on the phone one day? She said, “They’re going to kill me, if I’m not careful.”’

Jay’s grip tightened further and as the ferret squirmed uncomfortably Lachie took her back in case she would bite and returned her to his pocket. A man of few words, he didn’t know what to say except, ‘Told your dad, have you?’

Tears welled up. ‘He said she didn’t mean it, she was just talking about how she was having to deal with people being difficult, that was all. But is that what she meant?’

How would Lachie know? It was the sort of thing folk said, after all, and it wasn’t his place to have an opinion. He shrugged. 14

‘He’d likely know,’ was all he said. But as Jay looked at him for a long minute before turning away, he felt uncomfortable – maybe he should have told him to tell the polis. But it wasn’t his way to look for trouble and after the boy had gone he went back to his task, securing the last pegs around the net so that the ferret could be released to do her work of darkness.

CHAPTER ONE

2023

Oriole Forsyth felt sick, anxiety like a stone in her stomach as she took the winding road to Inverness to see the lawyer. She’d pretty much been feeling sick ever since her father had died, but just now it was the problem of the Drumdalloch Woods that was on her mind.

She’d adored Giles and with his woods seeming almost a part of him she’d tried to love them too, even though she found their shadowy darkness and tangled growth and dank smell oppressive and even sinister; she had nightmares about being lost in rain and darkness with trees creeping closer and closer. Hungering for his affection, she’d hoped showing enthusiasm would bring them closer together, but she was afflicted with a sort of awkwardness that had got in the way of real closeness – and perhaps that went for him too, though it hadn’t been a problem for bloody Helena.

Her sister-in-law had been blessed with the gift of 16charm, sadly denied to Oriole. She still bore the scars from coming in with the exciting news of herons nesting in the small remnant of the Great Caledonian Forest on the edge of the estate.

She’d known what it would mean to Giles and was looking forward to enjoying his pleasure, but it was Helena who had visibly glowed, grasping Giles’s hands in delight and crying, ‘Come on, we have to go right now to see!’ He’d laughed and let himself be led, not waiting to hear Oriole say it would probably be better not to disturb them too much. She really hated Helena at that moment.

After the accident it should have been Oriole’s time, but it seemed Giles had been broken by it. Grief took away his interest even in his birds; he lost appetite, dwindled before her eyes. She’d often thought sadly, as he pushed away a meal she’d laboured over to tempt his appetite, that if she’d died instead he’d hardly have minded provided he still had Helena.

Helena’s husband had grieved less visibly–imperceptibly, really. Perry had always worked in Edinburgh through the week and often didn’t make it back at the weekend; Oriole had often wondered about the state of their marriage, but that sort of thing they didn’t discuss in their family, even if the locals might. Now he was just going on as he always had.

When it came to Helena’s son, though … Jay had become frankly impossible. He was traumatised and deeply unhappy and seeing his pain she’d done everything she could to reach out to him, but she couldn’t break through his unremitting hostility. He seemed to exude hatred, as if blaming her for being alive when his mother was dead. 17

When he was born she’d been enchanted; he’d been a bright, attractive toddler and they’d been great pals, the two of them – him and his Auntie Rorie. He had been a joy, in a life of duty where joys were scarce. It was later he’d become difficult, perhaps because Perry had been an absent father and Helena had spoilt him, inclined to laugh when he was just plain rude. She’d become ‘Aunt Oriel’; losing the childish nickname was painful. She’d been sorry for him, too; he wasn’t the happy child he’d been.

After Helena’s death Jay had begun refusing to accept limits of any kind, often disappearing for hours on end; once or twice they’d called the police and then looked stupid when he sauntered back in. He would climb trees and scare researchers by dangerously dropping down on them, but any rebuke would result in a temper-tantrum that wouldn’t have disgraced a two-year-old – and Jay was quite a big lad. Talking had no effect; he wouldn’t listen and since he didn’t scruple to hit her when he was in a temper she’d begun to be physically afraid of him.

Perry had made no concession to the changed circumstances, and with Giles depressed and helpless, the problem of Jay landed squarely on Oriole’s shoulders. However hard she tried, whatever she did, he only got worse and when she’d got a black eye trying to get him into the car to take him to school when he didn’t want to go, she’d given up. She let him do whatever he wanted, hoping he wouldn’t kill himself, or someone else, before Perry came for the weekend.

She confronted him as he stepped out of the car. ‘Your son – your problem,’ she’d said. ‘He badly needs help but he won’t accept it from me,’ and shut herself in her room. 18Perry hadn’t reacted well, but at least he’d taken Jay back with him, then sent him to board at a private school. He’d settled there all right, she assumed, since Perry hadn’t said any more about it.

She wasn’t expecting good news from the lawyer. It was well over a year since Giles had died and all that Muriel Morris could say was that probate hadn’t yet been granted, despite HMRC demanding death duties be paid before she and Perry had seen a penny. They’d had to borrow to pay and now interest was mounting up she was struggling.

It was all right for Perry with a well-paying job, courtesy of family connections with the wealthy Forsyths, the senior branch of the family who owned an Edinburgh property business. Oriole, with so much time having been given over to looking after Drumdalloch and her father, had only a part-time job as receptionist at Steve Christie’s spa hotel in nearby Kilbain.

Giles’s estate had been left to his children equally, the house and woods to be shared and always there to provide a home for them both. Perry was determined to ignore his wishes and sell to the highest bidder for development; her loyalty to Giles made her baulk but she could see they’d have to sell up or starve. Anyway, until they were legal owners there was nothing they could do.

Perry, in Edinburgh full-time now, had been happy for Oriole to make it her home meantime, on the assumption she would look after it, along with the woods. Her attempt to get him to pay towards upkeep had failed; he’d pointed out she was living there rent-free, making considerable play of the cost of renting his flat in Edinburgh’s Northumberland Street. 19

She could have said this was one of the smartest streets in Edinburgh, while she was living in a house with a wing abandoned after being ravaged by fire long ago and now spreading rot into the rest of it, allowed in her father’s time to crumble quietly. But since she’d never won an argument with Perry, she’d saved her breath to cool her porridge and come up with the idea of an Airbnb.

The trouble was people had high expectations now and she hadn’t the money to provide luxury, but she’d managed to carve out two bedrooms and a living-room-kitchen on the first floor to be an acceptable flat that brought in a useful, if sporadic, income.

But she’d had another idea too. The Scottish Institute for Studies in Biological Sciences had been having free run of the woods for decades without contributing, and while Giles had never considered charging them for access, it seemed only fair to Oriole.

It didn’t, apparently, seem fair to the Institute’s director, Dr Michael Erskine. When she’d approached him to negotiate a suitable fee, he’d been dismissive.

‘We’re operating on a shoestring as it is. What do you need money for?’

Eating, keeping a roof over my head that doesn’t need buckets to sit under the leaks … She didn’t think he’d be interested in that; ‘Costs,’ she said.

He sneered openly. ‘What costs? The place is just left to run wild.’

Giles had believed in letting nature do its own thing, as being better for wildlife and the trees too. He had this theory that they looked after themselves, and even each other – the ‘Wood Wide Web’, he called it, and there 20were pioneering studies in train on that as well as the ornithological ones.

It had been all very well for Giles to be a sentimentalist. He’d inherited a lot of money from his grandmother, but he’d no interest in finance – or indeed, any other boring practicality – and it had drained away over the years; now, with death duties and rampant inflation, there wouldn’t be much left to trickle down to Oriole and Perry.

After that bad-tempered meeting she’d been determined not to go on being a doormat. She’d called the lawyer to arrange an appointment to talk over her plan, but the response had been guarded, much as it had been when she’d phoned Muriel Morris after Giles died to hear how much – or as it had turned out, how little – they were likely to inherit after the government had exacted its pound of flesh.

Which was why Oriole’s anxiety was feeling like a stone in her stomach as she drove to Inverness.

Muriel Morris glanced at her watch, then got up to fetch a thick folder from a bookshelf. Then after a moment’s thought, she took a key from a drawer and went to the huge old-fashioned iron safe that had stood in the corner of the senior partner’s office since she was a little girl – and come to that, since her father had been a little boy. She couldn’t vouch for her grandfather, but it was certainly possible.

She was a neat, precise woman in her fifties, always smartly groomed. As she took out a heavy metal deed box bearing the painted legend ‘Drumdalloch House’ and set it down on the desk she looked with disfavour at the dust 21it had left on her fingers and took a tissue to wipe it off. Its key was attached to the handle of the box and she sneezed as she opened it and more dust wafted up from the documents inside.

Her father had gone over the Forsyth papers with her when she’d stepped into his shoes as the first female senior partner of Morris Soutar – still so-called though the last Soutar had been killed in the Second World War – and she knew more about the family’s history than did any of its present members.

Morris Soutar had looked after the estate on the Black Isle, in Moray, since its purchase by Ralph Forsyth in 1883. He was doing well in property in Edinburgh when it was the thing to have a hunting lodge in the north, but Ralph was more inclined to the fleshpots of Edinburgh than to the stalking of stags across moors in what was usually shockingly bad weather, so Drumdalloch became mainly somewhere to send underoccupied children to run wild during the long independent school holidays.

When his son Robert had inherited in 1918, his wife Isabella, a minor heiress in her own right, chose to spend more time with the wonderful exuberance of the Drumdalloch Woods than with her admittedly dull husband – and, wicked gossip had it, with a certain young forester. When Robert died in 1946, she retired to it as a dower house with the ready agreement of her son William, Isabella having, apparently, a famously forceful personality. Ownership was transferred to her as part of her marriage settlement, and she had left it to her second grandson Giles, father to Oriole who was the next appointment in Muriel’s diary. 22

She sat down to wait with a sigh. There were difficulties ahead, and she couldn’t see any good news to offer. She was sorry for Oriole, who’d been left dealing with all the estate’s problems on her own; she was gauche and awkward, almost childlike sometimes in the black-and-white way she saw things, but she’d been very good to her father and done her best with her troublesome nephew. She was much more likeable than Perry, who always seemed to come in with chin stuck out and looking for a fight. Neither of them had inherited their father’s pleasant, easy manner and though Muriel had never known the mother who had died when Perry was five and Oriole three, she had dark suspicions about the woman’s character.

She’d had long talks with Giles Forsyth before his daughter-in-law died. His main concern had been the future of the historic woods; he was under no illusions about his son’s intentions. Helena had convinced him that in her hands they’d be safe, with Jay to tend the flame right into the future, and he’d told Muriel he planned to change his will in her favour.

It wasn’t her place to express an opinion, but she’d met the lady and assessed her charm as carefully calculated. Under tactful questioning, it had emerged that Giles knew nothing about his daughter-in-law’s background and Muriel was also extremely doubtful that Helena would be any more likely to preserve his beloved woods than his children were; indeed, it was hard to see where she’d get the money to do it. Giles had few extravagances, but his answer to any shortfall had always been to draw on the dwindling capital.

She was only doing her duty when she said, as tactfully 23as she could, ‘Any such bequest would undoubtedly be challenged, which always inflicts disastrous costs. Even leaving that aside, by the time death duties are paid and the bairn’s part deducted, there wouldn’t be enough money to keep the place going.’

He had looked startled. Giles was not a man who had ever permitted himself to be concerned about money and now he looked bewildered.

‘I don’t understand. I know about death duties, obviously, but “the bairn’s part?”’

It took some time for her to explain that by Scots law, half of a sole parent’s estate must be left to the offspring. He was both indignant and angry at this restriction, but agreed to think it over.

Then Helena had died. The next time Muriel spoke to him, she didn’t recognise the quavery, old man’s voice as being his. He’d called her to discuss bequeathing the woods to the Scottish Institute for Studies in Biological Sciences and she had again pointed out the problems; when he sighed and said, ‘I’m sure you’re right,’ he’d sounded defeated, and he’d died weeks later.

Now Oriole was coming in, proposing to charge the Institute for continued access and again she’d have to explain to a Forsyth about the unreasonable nature of the laws of the land. She sorted through the papers in the deedbox and lifted some to lay out for Oriole to read.

Her client came in late and frazzled. She was small and slight and somehow looked as if she were diminished by her problems. ‘There were roadworks on the Kessock Bridge,’ she said. ‘They just seem to be digging up the whole of the Black Isle. You wouldn’t believe the tailback, 24and the weather’s getting worse by the minute.’

‘Come and sit down and I’ll ask Mairi to bring coffee. I could do with it – these papers are so dusty my throat’s dry.’

The suspicious look Oriole gave them suggested she saw them as a threat – and she wasn’t wrong there. Like the sins of the fathers being visited upon the children, decisions by her great-grandmother were now about to burden the present generation.

Over coffee, they moaned about the injustice and inefficiency of the tax system, until Muriel said, ‘So tell me how I can help you,’ though she knew what she was going to say wouldn’t be helpful at all.

‘The Institute is being totally obstructive. Michael was positively unpleasant to me when I pointed out the woods now belonged to us, and I wasn’t prepared to let him and his students go on using them for nothing. You know how strapped I am for cash. Can you get something drawn up to deal with this?’

Muriel never liked having to break bad news. ‘Well, I’m afraid there will be some problems with that,’ she said, and saw Oriole’s face sag into dismay.

‘But why?’ she cried. ‘They’re our woods. Why shouldn’t I charge for access?’

Michael Erskine had appeared in Muriel’s office after his meeting with Oriole, a tall, confident man in his early forties, with the arrogance she’d often noticed in academics when dealing with lesser mortals. He’d talked about the importance of the research; she had responded with suitable platitudes. Then he had talked about the legal side.

Now, Muriel said to Oriole, ‘I’m afraid he’s prepared 25to play hardball.’ She sorted through the papers on the desk, stiff with age, and pulled out one. ‘He says your great-grandmother, Isabella Forsyth, gave the Institute permission to use the site and this is the document giving unrestricted access.’

Oriole looked at it with distaste. ‘Well, I knew that. But this was long ago. The woods are ours now.’

‘Indeed, but during your father’s time there was no suggestion the situation had changed. Evidence of customary practice, what was known as “use and wont”, over a period of years with no objection may convey certain rights.’

Oriole went very still. ‘You mean Michael can just tell us what we have to do?’

‘He’s prepared to go to law. If you contested it you might win, but it would be an expensive business and in my professional opinion a favourable outcome would be very unlikely.’

Tears came to Oriole’s eyes. ‘You know we can’t afford that,’ she said bitterly. ‘Are you saying that this will go on tying us down for ever? I’ll tell you one thing – I’ll stop organising the Friends of Drumdalloch Woods so the paths can grow over, and if trees fall I’ll just leave them there …’

Muriel cleared her throat. ‘Er – I think you’d have to be careful. I was going to mention taking out insurance as protection against any possible injury claims.’

The tears had started falling and Oriole dabbed at her eyes with a tissue. ‘But where can I find money to pay for that? What can I do?’

‘Perhaps Perry—’ 26

Oriole’s response was to give a disgusted snort. ‘Perry? He won’t lift a finger. He’ll just say Drumdalloch is my responsibility until we’re able to sell it.’

She stood up, blowing her nose. ‘There isn’t any point in going on with this, is there? I’ll just have to do what I can. At least I’ve a few bookings lined up on Airbnb – it’s all that’s keeping my head above water.’

Muriel let her go. There seemed no point in depressing her further by telling her she strongly suspected that Erskine would try to get a preservation order put on the woods as a Site of Special Scientific Interest. They’d escaped having one earlier since, apart from a protected small group of ancient Caledonian pines, it wasn’t native woodland; Isabella had consistently treated the place as if it was only a very extensive garden and, in much the same spirit as a collector choosing exotic stamps, she had overwhelmed the straggly native birch and ash with trees like the monkey puzzle, to be admired by the pergola, and a magnificent redwood to add definition to the skyline.

The only time Muriel had visited, the pergola had been reduced to a ramshackle pile of struts and the only reason the place wasn’t totally overgrown was because the deer, like the Institute’s students, had unfettered access, but there were also impressive ancient trees, like mahogany and walnut, which Giles had informed her were difficult to grow even in the rich black soil that had given the peninsula its name, and succeeding had been his grandmother’s proudest boast.

It might once have been Isabella’s pleasure ground, but it wasn’t much of a commercial asset as it stood – and if Michael Erskine did manage to get the order, all the 27Forsyths would realistically have to sell was a house well past any sort of renovation.

As Muriel tidied the papers back into their strongbox, she sighed. Oriole might lack her sister-in-law’s charm but she’d given up a proper life of her own to look after her father – and his wretched woods – quite devotedly. Some people didn’t have much luck.

Perry Forsyth sat in the Edinburgh New Town office of Forsyth Property across the desk from his cousin Edward, staring at him blankly.

Edward shifted uncomfortably. With his bespoke suit and well-cut hair, he had the gloss of good living about him, financed by his position as senior partner in a successful and long-established firm, but he was only five years older than Perry and it was an interview he would have been happy to dodge. In the circumstances, though, there was no alternative to wielding the axe himself.

‘You have to understand times are really hard, Perry. I absolutely hate having to do this, but with inflation and the slump in the property market we’ve got no alternative but to retrench.’

‘Well, of course I know that. I work here, remember? And I’m family, Edward – oh, all right, I know we’re only the junior branch. I’ve never been allowed to forget it, after all.’ There was a hard, bitter edge to his voice. ‘And I’ve built up all this expertise over the years – surely that’s worth something?’

‘Certainly, certainly,’ Edward said. ‘We’ll miss you, of course.’ He was lying; they’d been trying for years to find an excuse to elbow out the cousin who was always 28on the verge of provoking formal complaints from staff about bullying and from clients about inefficiency, and the downturn had at last offered the opportunity.

Perry was scowling now. ‘I can’t believe what I’m hearing. And what happened to the principle “last in, first out”? Nick Mackintosh only came six months ago. Why are you saying this to me and not to him?’

Mackintosh was a bright, enthusiastic young man, good at his job and popular with everyone, but Edward could hardly say that. ‘I know, I know,’ he said. ‘Life’s a bitch, isn’t it? And it’s hard for me to do this too, blood being thicker than water.’

Perry’s darkening expression suggested this line wasn’t going down very well. He hurried on, ‘The thing is, we’re at the mercy of the accountants. We have to cut right back and with your salary reflecting your status and experience, they picked on this as a very significant saving. Naturally, there will be a generous redundancy payment and you’ll have time to find something else that makes the most of your skills. And you can pretty much write your own reference.’

Perry searched his face as if he was looking to find a different meaning for the words being said. There was a note of desperation in his voice as he said, ‘Look, I don’t think I’m overpaid, but I can see that there’s a problem. In the circumstances, I’d be prepared to take a pay cut.’

Edward almost groaned aloud. ‘I’m afraid the accountants wouldn’t accept that. As you said, you’re entitled to what you’ve been paid, and it wouldn’t be right. Thanks for the offer, though …’

He should have known that it wouldn’t be long before 29Perry’s notoriously short temper erupted. ‘Bloody hell, you really think you can get rid of me, just like that? I’ve never been properly valued. You’ve run a hopelessly sloppy operation, but when I did my best for the company and tried to get staff you failed to train properly to do the job they’re well paid for, did you back me? No, you didn’t. You allowed chippy little girls to get away with downright cheek to a senior manager.’

Edward had one more try at cooling it down. ‘Of course, I know you were trying to do what you thought best—’

He wasn’t allowed to finish the sentence. ‘And you didn’t agree,’ Perry shouted. ‘Oh, I knew that – it was bloody obvious. You’ve been looking for a chance to elbow me and the downturn’s given you an excuse. Well, I won’t go quietly. I’ll sue for wrongful dismissal.’

Little as Edward liked it, he had to take the gloves off. ‘If you did, we’d have to disclose the complaints of bullying and harassment. You remember we had to talk about this several times and after the most recent discussion we realised your attitude hadn’t changed and complaints were on the point of being made formal. We couldn’t have avoided sacking you and the downturn has actually worked to your advantage in allowing us to ease you out. But if you want to run with it …’

There was a long, angry silence. Then Perry got up.

‘OK, you win. Your lot always win. I don’t suppose this dirty trick will even trouble your conscience. What do I have to sign?’

When at last his kinsman had gone, Edward took out his handkerchief and was wiping the sweat off the back 30of his neck when the door opened and one of his partners appeared.

‘How did it go?’

‘Ghastly – but he’s gone.’ He fetched a bottle of Glenfiddich and a couple of glasses from a cupboard. ‘Join me? I know it’s early, but by God, I need this!’

Perry walked out into North Castle Street, lurching slightly, light-headed with the shock. It had never occurred to him that the position wasn’t his for as long as he chose to occupy it. In some hazy way he’d seen it as reparation due from the branch of the family that had grabbed most of the goodies inherited from their mutual ancestors.

Edward he had simply despised – weak, lax, ruled by the juniors – and if he, Perry, had been in charge he’d have run a tight ship and made it a more successful business, one that wouldn’t be having to make economies and sack staff.

Staff – like him. Without the job, he was nothing. If he applied for anything similar, he’d be offered a fraction of his current salary – and whatever gilded reference Edward provided, everyone in the property business would know he’d been sacked. The faint buzzing in his head could almost be the sound of messages whizzing around the internet.

The rain began as he emerged, typical Edinburgh rain: not dramatic, but politely steely in its persistence. His umbrella was in his office, but they’d escorted him out; they’d send everything round, probably in a black plastic bag, with an office girl smirking as she dumped it on him.

All he could do was go home to lick his wounds and 31he set off downhill towards Northumberland Street. But it wasn’t going to be home much longer, was it? Indeed, given the rent, he’d have to pull every string he still had to get out of it immediately; the redundancy money would have to keep him until they could flog Drumdalloch and God only knew when that would be – God and the sodding Inland Revenue.

And then there was James. He couldn’t afford school fees; removing him would be catastrophic, not because of the effect on the boy – that didn’t cross his mind – but because James would be permanently around, sulky and aggressive, which was painful enough during wretchedly long holidays. Claudia would walk out, for a start.

Anyway, she wouldn’t stay if he was penniless. She worked in Space NK in George Street; she’d sold him perfume for a girlfriend and then somehow the girlfriend had gone and she’d moved in. She was high maintenance and even if he ignored Oriole’s refusal to take responsibility and packed James off to Drumdalloch, it probably wouldn’t help. Even the most dismal flat in Edinburgh was expensive and Claudia wouldn’t settle for dismal.

He had to face up to it; in one day he’d lost income, home and girlfriend and acquired the ongoing problem of a son who looked at him daily with eyes narrowed in hatred.

There was only one thing for it. He’d have to go back to Drumdalloch himself.

CHAPTER TWO

Kelso Strang looked out of the window of the fisherman’s cottage that stood across from the harbour in Newhaven. It was a shame it was a dreary day, with heavy clouds and a blustery wind coming off the Firth of Forth; it was a very attractive view when the sun was shining, with the lighthouse at the end of the protective curve of the harbour wall, the colourful small boats at anchor and the view of Fife on the other side. He’d so much wanted the house to look nice for Cat – not that she hadn’t seen it before, but this was an important day.

He’d met Catriona Fleming only a few months before when their paths had crossed in the Sheriff Court; as a police officer he was giving evidence in a criminal prosecution and she was the advocate’s devil, working for nothing while her pupil master trained her. Despite an immediate attraction, Kelso, very conscious of the twelve-year age gap, had wanted to take it slowly but circumstances, and a certain determination on Cat’s part, 33had accelerated the pace of the relationship.

It was, though, important to him that she should have time and space to change her mind; he couldn’t bear to think that one day she might feel trapped with an ageing widower. He’d been anxious, too, to reassure her parents, Marjory and Bill Fleming, that he wouldn’t pressure her into an early commitment, even though Marjory had said sardonically that if he ever managed to pressure Cat into doing something she didn’t want to do, would he please tell her his secret since she’d never managed it.

And indeed Cat, for all that she was young, had shown no sign of drawing back from the decision she’d made well before he had. She felt he was being ridiculously scrupulous. ‘I just knew, right from the start,’ she told him, adding reproachfully, ‘You were very slow, actually.’

Of course, they’d talked about his wife, Alexa, so tragically killed in a car crash along with their unborn baby. Cat’s eyes had filled with tears when he first told her.

‘Poor Alexa,’ she said softly, ‘and poor, poor you. You loved her very much, didn’t you?’

Kelso found that his throat was constricted so that he couldn’t speak and she went on, ‘Don’t ever feel you can’t mention her. I won’t be jealous and I promise I’m never going to do the “do you love me more?” bit – that was then and this is now. And I think I’d have liked her – after all, she had good taste in men. But, of course, if you want to see jealous, try so much as glancing at another woman and I’ll scratch her eyes out.’

They’d ended up laughing and kissing and deciding that when her pupillage finished, she’d leave her shared 34flat and move in with him.

‘I warn you, I’m going to be just as broke as I am now when I put up my plate and have to wait for clients to come to me,’ she said. ‘Frankly, I’m going to have to be a kept woman and they’ll be saying I snared you for your money.’

‘I rather like the thought of being a sugar daddy,’ he said. ‘But once you get going on the big cases and police salaries are frozen for yet another year, it’ll be the other way round.’

And today she was moving in. He’d offered to fetch her but she’d said she’d just chuck the few things she’d kept at the flat in a taxi and come round. At about eleven, she’d said.

Kelso looked at his watch again. Almost half past, but then Cat was seldom punctual. He was nervous – not about Cat, of course not, but about how he would actually feel having changes made to his comfortable bachelor existence. He liked this room, but Cat would naturally, and rightly, have her own ideas about décor and arrangements and he was remembering, uncomfortably, how he’d resented his sister Finella’s reorganisation of the cupboards when she had briefly moved in with her small daughter Betsy. Would he find he couldn’t help minding when things were different?

There was the taxi now, turning into the paved square beside the house. From the sitting room, he hurried down the outside stair and had the door open before she could get out.

There was only a suitcase and a couple of carrier bags.

‘Is this all your worldly goods?’ he said, smiling. 35

She beamed back. ‘No, this is just to lull you into a false sense of security. All my real stuff is at home. Mum wondered if we’d like to go down to Galloway for lunch next Saturday and you can see the full horror then.’

‘Sounds good,’ he said, following her up the stairs. Lunch at the farm was always a treat; he had a lot in common with Marjory, who’d been a senior police detective too.

Cat drifted over to the window. ‘Shame it’s such a rotten day. This is such a special view.’

‘Yes,’ Kelso said, then added awkwardly, ‘Of course, you do know you can change anything you want – redecorate, anything …’

She gave him a level look. ‘That’s very kind and proper, but you know you’d hate it if I tore everything out and changed just for the sake of change. I told you, I think it’s a lovely room – clever colours and I like the paintings. But there’s one thing I do want – another comfy chair at the window opposite yours so we can both look out on a good day.’

He felt the tension ease. ‘Go and sit down now and I’ll bring another one across once I’ve got the champagne out of the fridge.’

‘Oh good. I hoped there would be champagne,’ she said.

She sat down with a contented sigh and he looked over as he removed the foil from the bottle. He’d always liked this room but now he realised there had been something missing all along; that other chair by the window, for her to fill. 36

It was a scary drive back from Inverness, especially when you were feeling helpless and profoundly depressed. Driven on a tearing wind, the storm was building and as Oriole Forsyth crossed the Kessock Bridge on her way back to the Black Isle the wind snatched at her elderly Kia so that she had to wrench it back into line, while from the inside lane lorries threw up bow waves of water; the squalls of rain were merciless so that even the wipers on their highest setting couldn’t cope and she was driving all but blind.

She found herself thinking there would be worse things than a crash that finished it all. What was there to go home for? The roof would be leaking and while there were basins placed under known leaks, a storm always opened up new ones in unused rooms that she probably wouldn’t find until they’d done more internal damage. She’d have to check out the Airbnb flat; she’d spent money she could barely afford to weatherproof it but when it was like this nothing was safe.

She dreaded arriving back. Her father had always enjoyed dramatic weather but when the trees roared like the ocean and lashed themselves into a frenzy of whipping branches, she’d always felt terrified even when he was there beside her, but she’d pretend to be brave. Now she was alone, driving along the avenue to the house below trees under siege by the elements, and no one knew better than she how little had been done to ensure that none of the great oaks would simply topple.

The forecourt was empty and the red sandstone Victorian house with its pointed eaves and fire-gutted wing falling into ruin was gloomy in the gathering dusk, 37even though it was only four o’clock. She parked as close as she could and leapt across to the cover of the rickety wooden porch and in the front door. It wasn’t locked; there wasn’t much worth stealing and the students and Friends of Drumdalloch had always had access when she wasn’t there if they wanted to use the loo or the kitchen, or just wanted shelter from the elements. They’d all have given up and gone home long ago.

The hall was very dark. Oriole had to grope for the switch as, shaking her head to release a shower of raindrops and wiping down her face with her wet hands, she made for the kitchen to get a towel and make a cup of tea. It would be warm there, at least, from the ancient Aga and she draped her saturated jacket over the top.

But when she put the light on, her low mood changed to sheer rage. The kitchen was a complete mess, the table covered with dirty mugs, plastic sandwich packets and the remnants of someone’s lunch; there was a pan on the side of the Aga that had been used to heat soup, presumably from the tin left empty on the surface beside it. No one had made the smallest effort to clear up, merely leaving everything for her to deal with when she came in.

Not that it was unusual. When she was at home, she might nag mildly but she’d usually just put used mugs in the dishwasher and rubbish in the bins in passing, so if she was out at work as she had been today their detritus did tend to accumulate. It was admittedly irritating but she’d never got up enough of a head of steam to take a stand.

So she’d only herself to blame for letting them get away with it, but particularly after Giles died she’d rather enjoyed doing a bit of mothering; they were mostly little 38more than kids and it was company in this big empty house.

Today, though, it was simply too much, on top of all that had happened. As of tomorrow, she was going to harden her heart because it had to be different. If the Institute wouldn’t pay to use the woods for their stupid research, they’d have to pay for the privilege of parking at the house. And if they wanted what might be termed use of the facilities, they could pay for that too, or drive the five miles into Kilbain and find a café with an indulgent owner, always supposing they could find one.

She’d go on looking after the Friends who voluntarily did so much, of course, but there would be no concessions for the students, and particularly not for Michael Erskine when he rolled up in his lordly way, as he did from time to time to see how they were getting on. What was more, she wouldn’t allow him just to pop in to charge his ostentatiously eco-friendly electric car when it suited him, even if he offered to pay, which often he didn’t. Calling out the Kilbain garage to get it going again would be both expensive and time-consuming for him.

She didn’t look forward to telling Lars, though. Lars Andersen was working on a PhD in evolutionary biology, a black-haired, black-bearded giant who took himself and his work very seriously indeed, a Norwegian whose English, Oriole always felt, was probably more correct than her own even if occasionally awkward. She had never understood what it was all about, except that it had something to do with fungal networks that established themselves underground and nourished the trees in exchange for the sugars they needed in some sort 39of symbiotic relationship – or roughly like that, anyway.

He always worked as if he was running a race and was determined to bulldoze everything aside on his way to the winning post. Giles had explained to her that he probably felt he was, since scientific papers were a competitive business and being the first to get a new theory published in Nature, the science journal, could have career-changing consequences.

Oriole was, to be honest, afraid of his temper. Delays of any kind bought on his black mood, and she would go out of her way to avoid him on days like today when it was simply too stormy for outdoor work. He’d establish himself in the kitchen, moodily making notes and scanning tables and drumming his fingers while he checked out of the window every ten minutes to see if it was brightening up.

Well, he’d have to go and drum his fingers somewhere else. She was under no obligation to put up with his bad temper. When he’d first arrived two years ago, she’d actually rather fancied him – he was good-looking if you went for the rough-hewn look, with those intense brown eyes, but from the start he’d behaved as if he barely saw her. When it came to Helena, on the other hand …

Oriole had thought of saying something to Perry about what she saw going on, but she didn’t think he’d appreciate it, and they most certainly wouldn’t.

She’d appointed herself a voluntary student, though, ready to help with the ornithological studies and doing checks for Lars on the trees, which had not only allowed them to spend a lot of time together but had given Helena an excuse for not doing her share around the house. 40

Not that they didn’t have their rows. She’d hear them yelling at each other sometimes, and when Helena’s smiley persona slipped she could be quite a hellcat. The vicious row she’d overheard in the woods shortly before Helena died had been something to do with the preserving of what he definitely saw as his own personal woods, but it was odd that they should be arguing, given Helena’s frequently expressed enthusiasm for precisely that; it had made her think, not for the first time, that her sister-in-law was as two-faced as they came and was playing a deep game. She’d certainly had Giles exactly where she wanted him and Perry had been afraid his wife would convince him she’d protect the ‘legacy’ of the woods when he wouldn’t, and that his father would leave everything to her.

The estate was theirs now, but they were living in limbo with the struggle over the future still ahead. Even if she could never love the trees, she would badly miss the delights of the birdlife they sheltered, and she dreaded too the guilt she’d feel if she couldn’t persuade Perry to respect Giles’s wishes. And what was there for her anyway, once it happened? This place was all she’d ever known and even thinking about … well, afterwards, sent a shiver down her spine.

She shook herself out of it. Standing here going over ancient history wouldn’t help the untidy kitchen and she sighed, then went to stack the dishwasher and clear up with a bad grace.

By the time she’d finished, the wind seemed to be dropping as quickly as it had blown up. The trees were much less agitated, so she didn’t feel so nervous about the dangers of the drive, and since it was still only five o’clock 41she’d be facing a long and lonely evening here. She wasn’t on duty at the hotel but it would be company and Steve would be pleased to see her. She liked to think that the warmth of the hug he always gave her when she turned up unexpectedly showed genuine affection, though a cynical little voice at the back of her head tended to point out that with staff so hard to come by and so unreliable, an extra – unpaid – hand behind the bar would make any boss feel affectionate.

She wasn’t self-delusive; everybody loved Steve, always so personable and charming, so why ever would he be specially fond of Oriole, who was reminded by the mirror every morning of the heavy eyelids and deep-set eyes which, along with the downturned mouth, made her look depressed even when she wasn’t. Her father had always said she was very like his grandmother, and she’d worked out quite early on that this wasn’t a compliment.

After everything today, she was feeling as gloomy as she looked but seeing Steve was always a tonic. She mustn’t show how she was feeling; other people’s woes and complaints were very boring so she must put on a big smile and do her best to look cheerful.

Steve Christie was standing in the front hall of the Kilbain Hotel and Spa when Perry Forsyth’s phone call came through. Aware that the loud tirade that began the moment he answered it was clearly audible to the receptionist and the guests checking in, all trying not to look as if they were listening, he grimaced and stepped through to the office.

Perry Forsyth, thick and arrogant, wasn’t his favourite 42person; they were ‘mates’, theoretically, but he’d have choked him off long ago if there hadn’t been powerful reasons not to. Perry would one day have the Drumdalloch estate, while Steve had nothing beyond the grandly named Kilbain Hotel and Spa whose future was uncertain to say the least.

The hotel was distinctly shabby. The ‘spa’ consisted of a small indoor swimming pool, a room with weights and a treadmill, and a beauty salon that was meant to be offering treatments and hairdressing but couldn’t since the beautician had left for a better-paying job. Guests were very sophisticated nowadays and it was only keeping up a constant, exhausting charm offensive to deal with complaints that kept it going at all; he didn’t have the money to upgrade, and he’d be stuck with that for ever.

The grand project Steve had been involved in planning long ago had fallen through disastrously, but they’d moved their feet now to concentrate on Perry instead, drawing him in, talking about the killing they could all make together and the returns they would get on their investment. The worry was that once Perry, with his nice cushy job, got his mitts on the inheritance, he might simply blow the money – and of course Oriole’s opinion wouldn’t count.

So he heard what Perry was saying with sudden excitement, realising the big moment had actually arrived; with the man clearly shaken and vulnerable, it was the perfect time to lock him into a rock-solid business that would make all the difference to future prosperity. He was happy to make sympathetic noises as Perry’s fury talked itself out, while he tried to finesse his response. 43

He was genuinely surprised at the news because he’d always got the impression Perry only had the job at all because of some kind of family arrangement – Perry had bent his ear often enough about the wealth of his cousins compared to what he termed his own penury, even though that had allowed him a pretty cushy lifestyle.

If that wasn’t right, then Perry being sacked wasn’t surprising in the least. It was amazing he’d lasted there as long as he had; he’d always stigmatised the boss and his fellow-workers as incompetent fools and knowing the man, it was unlikely he’d have kept his opinion to himself. From Perry’s accounts, too, of run-ins with junior female staff, he’d often thought that with the spread of the ‘MeToo’ message he was living dangerously. And now it had happened.

‘God, mate,’ he said when Perry paused for breath, ‘that’s rough. Hope you’re going to take them to the cleaners.’