Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

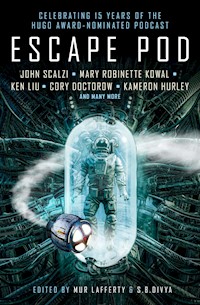

Celebrate the fifteenth anniversary of cutting-edge science fiction from the hit podcast, Escape Pod. Featuring new and classic stories from Cory Doctorow, Ken Liu, Mary Robinette Kowal, Ursula Vernon and more. From editors Mur Laffterty and S.B. Divya comes the science fiction collection of the year, bringing together bestselling authors in celebration of the publishing phenomenon that is, Escape Pod.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 405

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword by Serah Eley

CITIZENS OF ELSEWHEN

Kameron Hurley

REPORT OF DR. HOLLOWMAS ON THE INCIDENT AT JACKRABBIT FIVE

T. Kingfisher

A PRINCESS OF NIGH-SPACE

Tim Pratt

AN ADVANCED READER’S PICTURE BOOK OF COMPARATIVE COGNITION

Ken Liu

TIGER LAWYER GETS IT RIGHT

Sarah Gailey

FOURTH NAIL

Mur Lafferty

ALIEN ANIMAL ENCOUNTERS

John Scalzi

A CONSIDERATION OF TREES

Beth Cato

CITY OF REFUGE

Maurice Broaddus

JAIDEN’S WEAVER

Mary Robinette Kowal

THE MACHINE THAT WOULD REWILD HUMANITY

Tobias Buckell

CLOCKWORK FAGIN

Cory Doctorow

SPACESHIP OCTOBER

Greg van Eekhout

LIONS AND TIGERS AND GIRLFRIENDS

Tina Connolly

GIVE ME CORNBREAD OR GIVE ME DEATH

N.K. Jemisin

Acknowledgements

About the Editors

About the Contributors

ESCAPE POD

THE SCIENCE FICTION ANTHOLOGY

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Cursed

Dark Cities: All-New Masterpieces of Urban Terror

Dead Letters: An Anthology of the Undelivered, the Missing, the Returned…

Exit Wounds

Hex Life

Infinite Stars

Infinite Stars: Dark Frontiers

Invisible Blood

New Fears: New Horror Stories by Masters of the Genre

New Fears 2: Brand New Horror Stories by Masters of the Macabre

Phantoms: Haunting Tales from the Masters of the Genre

Rogues

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands 2: More Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands: The New Apocalypse

Wonderland

ESCAPE POD

THE SCIENCE FICTION ANTHOLOGY

EDITED BY

MUR LAFFERTY & S.B. DIVYA

TITAN BOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Escape Pod: The Science Fiction Anthology

Print edition ISBN: 9781789095012

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789095029

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: October 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Foreword © Serah Eley 2020

Citizens of Elsewhen © Kameron Hurley 2018. Originally published on Patreon.

Reprinted by permission of the author.

Report of Dr. Hollowmas on the Incident at Jackrabbit Five © T. Kingfisher 2020

A Princess of Nigh-Space © Tim Pratt 2020

An Advanced Reader’s Picture Book of Comparative Cognition © Ken Liu 2016.

Originally published in The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Tiger Lawyer Gets It Right © Sarah Gailey 2020

Fourth Nail © Mur Lafferty 2020

Alien Animal Encounters © John Scalzi 2001. Originally published in Strange

Horizons. Reprinted by permission of the author.

A Consideration of Trees © Beth Cato 2020

City of Refuge © Maurice Broaddus 2020

Jaiden’s Weaver © Mary Robinette Kowal 2009. Originally published in Diamonds in the Sky: An Original Anthology of Astronomy Science Fiction edited by Mike Brotherton. Reprinted by permission of the author.

The Machine That Would Rewild Humanity © Tobias Buckell 2020

Clockwork Fagin © Cory Doctorow 2012. Originally published in Steampunk! edited by Kelly Link and Gavin J. Grant. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Spaceship October © Greg van Eekhout 2020

Lions and Tigers and Girlfriends © Tina Connolly 2020

Give Me Cornbread or Give Me Death © N.K. Jemisin 2019. Originally published in A People’s Future of the United States, edited by Victor LaValle and John Joseph Adams. Reprinted by permission of the author.

The authors assert their moral rights to be identified as the author of their work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

ESCAPE POD

THE SCIENCE FICTION ANTHOLOGY

TO SERAH ELEY AND EVERYONE WHO SUPPORTED ESCAPE PODOVER THE PAST FIFTEEN YEARS. ONE GOT US STARTED,AND THE OTHERS KEPT US GOING.

FOREWORD

I have a “thing about” story. Here is a story about that.

In 2005 I was a guy named Steve, living a very different life than I am today. Things were good. I had a wife and an infant son, a house in the suburbs, a dog named after a Final Fantasy character—all the markers of mainstream American success. Of course, I thought I was weird. I had weird geeky friends (by my standards of the time) and did weird geeky stuff like role-playing and writing science fiction. I was even romantic in weird geeky ways: when my wife and I went to bed at night, I’d read to her. Neal Stephenson, Vernor Vinge, Terry Pratchett, whatever I thought was fun.

I know, I know. I was young and innocent, okay? Or at least innocent. I was a cis straight white guy who truly thought I knew what weird was, because I read science fiction. “Adorable” is the word that comes to mind now, but I was just making the same mistake almost everyone makes: I believed the world of my own experience was a representative sampling.

Early that year, I read on a geek news site about a nascent internet fad called “podcasts.” People were making all sorts of audio and pushing it out on blog feeds. I went looking and found dozens of these things—and some of them were good! One of my favorites was a freewheeling romp of personality called Geek Fu Action Grip by Mur Lafferty. She talked about everything: her childhood, her media obsessions, drinks she invented based on her crush on Keanu Reeves… Her openness and wit helped me realize how accessible and how personal podcasting could be. I wanted to be like her and the other pioneers I was enjoying. I wanted to make something.

I spent a few days pondering fresh ideas. Some were clever, some were quirky, none excited me for long. The top candidate was a political podcast from an AI who was cynical about humans. That might have worked, but I feared becoming even more cynical myself if I succeeded. The obvious truth finally hit me in bed one evening, as I was reading a Harry Potter novel to Anna. I was already making audio entertainment—I was doing it right that second! I’d been producing it for an audience of one, but I could expand that with a bit of work.

Podcast fiction was already an established art form; several excellent authors had been narrating their own novels for months. I hadn’t heard of anyone reading other people’s work, though. Short fiction seemed like a practical fit for the medium, and I had friends who’d run science fiction webzines, so that felt like a familiar model. Most of all, I’d been a writer long enough to hold one value sacred: Writers get paid.

That was the origin of Escape Pod. I hit up friends in my writing group for the first few stories, shoving a contract and $20 at them whether they wanted it or not. I did the site design myself and commissioned a logo from another friend, Douglas Triggs, for a case of his favorite ginger ale. (The name of the podcast was the only spec I gave him; the gorgeous starscape with the exploding spaceship was all his idea.) I had once been to a Rasputina concert and been blown away by the opening band, a bunch of Alabamans wearing kabuki masks thrashing out monster-movie surf rock. I emailed Daikaiju and explained my project in a few hundred words; they replied with a dozen words of permission to use their music.

I bought the wrong microphone and the wrong amplifier, made other exciting technical mistakes, and spent six weeks recording the first story (“Imperial” by Jonathon Sullivan) over and over, never satisfied with my own delivery. I finally realized that if I demanded perfection before I started, I was never going to have a podcast at all. I put the first episode online the next day, announced it on the Yahoo! email list that was the focal point of 2005’s podcast community, and dropped a couple of lines to some SF market listings. Then I got to work on the second episode. I’d bought just over a month’s worth of content, so I resolved to try at least that long before deciding if I’d failed. I’d had fun either way, so it wasn’t time wasted.

One week later I had just over a hundred downloads, which was a blockbuster success for a new podcast of that era. And a British fellow named Salim Fadhley had already donated $5 from the site’s PayPal link. (Sal was a hardcore indie arts advocate who went on to help me in countless ways, and I’m grateful for his friendship.) Story submissions started to trickle in by the second week, and enough were worth buying that I began to think this might be sustainable. I started to reach out to other podcasters to narrate stories I didn’t think I could read well—especially those with women protagonists—and found out that community collaboration like that was the best possible networking.

The next few years were a gradual ascent towards Real Professional Success that would have terrified me if I’d known any of it at the start. I formed an actual business, Escape Artists Inc., to get all of those donations and story payments out of my personal checkbook. I printed up bookmarks to give out at conventions, sat on panels as a guest, and schmoozed at industry parties. Eventually we hosted some of those parties. We launched a second podcast for horror stories, PseudoPod, and later a third for fantasy, PodCastle. We bought a fancy machine that burned and printed labels on CDs in bulk and sold podcast collections as gifts. I found out the hard way that my ADHD brain is really bad at business, so I roped another podcasting friend, Paul Haring, into taking on the accounting and management. I nearly broke his sanity and am amazed that he still talks to me.

Success was quite fun and interesting, but one of my bad-at-business signs was that the audience numbers and the dollars never felt fully real to me. I was aware of them as facts but didn’t know what to do with them. People felt real to me, and I shared words with a lot of fascinating people—listeners and podcasters and writers. My world grew a little with each new connection. Most of those people gave me at least a few moments of pleasure; some became core to my life; a very few were abhorrent to me. But I never met or heard from a boring person. I used to think boring people existed; I don’t any more.

Hey! Wake up! This is the really important part. The bridge to the chorus. Everything I have said so far is true, but it didn’t happen to me. Steve Eley of 2005 and Serah Eley of today are not the same person. Yes, sure, I started with his body, but we have completely different stories. Telling his Escape Pod story in first person has been feeling increasingly awkward, so I’m going to drop the pretense and speak for myself.

Steve was paying lip service to a philosophy of “Story” long before he started his podcast. He had a whole spiel about the human need for mythology, about our rapidly changing society, the role of science fiction as the literature of change, the vitality of short fiction as the purest expression of ideas, et cetera. Becoming an editor and speaking at cons gave him chances to talk about these ideas, to polish them to a fine gleam, to be a Voice of Authority™.

This was both good and bad for him as a person, but he did get good at performing it, and he believed everything he said.

I have a different opinion of his “Story” theories. I think that, for the most part, they’re rarefied bullshit of the sort that white men who edit SF have been spouting at least since Campbell, if not earlier. Steve had exactly one principle that delivered real value to the genre through his editing, and he expressed it best in two words at the end of every episode: “Have Fun.” He got that totally right. Everything else, he made too complicated.

Story isn’t some grand capital-S ideal to be dissected or worshipped. Story is basic. It’s the essence of all human experience. Our senses take in an overwhelming amount of data, but we only care about the parts that we can attach to mental models of causes leading to effects. Those are stories. We all live in the same physical world, but experience it differently depending on the stories we believe. Our own identities are just contiguous chains of memories: a story about ourselves that we tell ourselves and others. Steve’s self-story started soon after he was born in 1974. Mine started in 2013 (and is spectacular, but way beyond the scope of this foreword). That’s how I know we’re different people.

Every meaningful experience is a story. Every memorable interaction with someone is a story, and often involves the telling of other stories. No story that means something to us is ever boring; boredom just means we stopped paying attention. That’s why Steve stopped believing in boring people. His philosophy had nothing to do with it; he just found out that he really liked paying attention to people.

True stories and fictional stories work the same way in our minds. There are no fundamental differences; we can only tell them apart by context. That fact has plusses and minuses, some of which have become screamingly relevant in today’s world. But one of the plusses is that fiction has as much power to expand our inner worlds as truth. Cataclysmic fiction can teach us things with none of the risk and mess of a real apocalypse. Fantastic fiction can make us feel way more interesting than stodgy physical reality wants to allow. And so on. That you’re reading a science fiction anthology means I’m preaching to the choir.

“Expanding worlds,” though—that’s the theme that keeps coming back. When good fiction, direct experience, and other people all have the same effect, something interesting must be happening. Something real. I’m writing this in the summer of 2020: the year of coronavirus; of Black Lives Matter; of rising American fascism. These are revolutionary times. Through my own weirdass transgender lesbian lens, the revolution looks like people with small worlds trying desperately to hold fast to their power and relevance, cowering before a tidal wave of larger, more colorful worlds. That sense of revolution is strong in this anthology, too, because Mur and Divya know very well what worlds they’re living in and what they’re doing.

Steve started to feel burnout in 2010. He’d been putting up an episode every week for five years, almost without fail, while working a full-time job and being a family man and having multiple polyamorous relationships. He also went to cons and played games and goofed off a lot. I have no idea how he did it. The funny thing is that he felt unproductive and irresponsible the entire time, and was never fully convinced he was good at Escape Pod. But he knew he’d made something people cared about, and he was smart enough to leave his company with people who cared about that. I honestly believe that Alasdair Stuart is the most clueful man in the industry today, and that Mur and Divya have made Steve’s little hobby project into one of the strongest, most diverse, and most important voices in modern science fiction.

This book is an extension of that work. Some of the authors and stories are familiar, but the style of others is often a significant departure, because what works in audio and what’s possible in prose aren’t always the same. The energy here runs up and down a tension line between provocative and fun, but there’s one common thread in every piece: a yearning, palpable sense of humanity. These are revolutionary times, after all, and Mur and Divya know what they’re fighting for.

It’s customary here to say a few words on each piece. I’ll do my best to avoid spoilers, but if you want a fully clean slate, my feelings won’t be hurt if you skip on to the first story.

• Kameron Hurley’s “Citizens of Elsewhen” is about midwives, and a poignant morality tale about the balance between present and future.

• T. Kingfisher’s “Report of Dr. Hollowmas on the Incident at Jackrabbit Five” is also about midwives, but with a different tone. It’s one of the funniest SF midwifery stories I’ve ever read, and certainly the funniest involving a goat.

• Tim Pratt’s “A Princess of Nigh-Space” starts with a familiar fantastic trope, and then doesn’t invert it so much as overruns it with a flanking maneuver.

• Ken Liu’s “An Advanced Reader’s Picture Book of Comparative Cognition” is beautiful, grand in scale, and at the same time deeply personal. Some of these alien races are going to haunt me for a while.

• I shouldn’t claim favorites, but Sarah Gailey’s “Tiger Lawyer Gets It Right” is my favorite. All I can say is that there’s a tiger in it. That’s enough.

• Mur Lafferty’s “Fourth Nail” is full of privilege and intrigue, both of which are inevitable with human cloning. Like many clever hard SF stories, it stands on its own while evoking the sense of a much larger world and story.

• John Scalzi’s “Alien Animal Encounters” is a laugh-out-loud set of vignettes about people who didn’t know what they were getting into. There’s sex, drugs, and sadness here, all of it ironic.

• Beth Cato’s “A Consideration of Trees” is deft science fantasy. The protagonist is a palimpsest of metastory and magic, at home on a space station with familiars and faerie.

• Maurice Broaddus’s “City of Refuge” is the most down-to-earth story, focusing on an ex-convict in a world that barely feels different from today.

• Mary Robinette Kowal’s “Jaiden’s Weaver” will draw tears from anyone who’s ever deeply loved a childhood pet. Or anyone who was ever a child. And also me. It’s beautiful and heartfelt.

• Tobias Buckell’s “The Machine That Would Rewild Humanity” is a post-singularity tale with a novel dilemma: if we are replaced by our creations, will they care enough to preserve us? Should they?

• Cory Doctorow’s “Clockwork Fagin” yanks Dickens into the steampunk age, with lively prose that maximizes revolution and fun.

• Greg van Eekhout’s “Spaceship October” follows with more downtrodden children, on a generation ship harboring injustice and secrets. It’s simple and satisfying, unless perhaps you’re one of the 1%.

• Tina Connolly’s “Lions and Tigers and Girlfriends” is my winner for pure fun. There’s revolution, but more importantly, there’s high school theater. And the cutest of awkward teen romances that set my little gay heart aflutter.

•Finally, N.K. Jemisin’s “Give Me Cornbread or Give Me Death” is a brutally clever story of racism and dragons. This is the piece that most enlarged my world. I was cringing or cheering or both with nearly every sentence.

Reading these stories was a pleasure, and writing this foreword has been a privilege. I’m proud of what Mur and Divya have done, and proud of what the entire Escape Artists team has done in the past ten years to bring smart fun short fiction to more and more people. They’re making worlds bigger. They’re making the world, the one we all share, better.

Enough from me. To quote someone whom I love and respect dearly: “Iiiiiiiit’s story time…”

SERAH ELEYJuly 31, 2020

ESCAPE POD

THE SCIENCE FICTION ANTHOLOGY

Kameron Hurley is not reticent to express her opinions, whether that’s in journalism or fiction. Perhaps that’s why she’s won multiple awards for her writing. Her essay, “We Have Always Fought,” explores the history of women warriors, erasure, and the narratives with which we deceive ourselves. When you read a Kameron Hurley story, you know you’re going to see your reality through a new lens, and what you see will likely challenge your assumptions. “Citizens of Elsewhen,” is no exception. We’ve published several of Kameron’s stories in Escape Pod, and we’re proud to open our anthology with this feminist time-travel tale.

DIVYA

CITIZENS OF ELSEWHEN

KAMERON HURLEY

“Soldiers are citizens of death’s grey land, drawing no dividend from time’s tomorrows.”—Dreamers, Siegfried Sassoon

* * *

We drop through the seams between things and onto the next front.

The come down is hard. It’s meant to be. The universe doesn’t want you to mess with the fabric of time. Our minds are constantly putting down bits of narrative into our brains, a searing record of “now” that gives us the illusion of passing time. In truth, there is only “now,” the singular moment. We are all of us grubs hunting mindlessly for food, insects calling incessantly for mates. Nothing came before or after.

But because time is a trick of the mind, it can be hacked. And we have gotten good at it. We had to. It was the only way to secure our future.

“Who’s got the football?” Elba says from the darkness beside me. “Lexi?”

“It’s en route,” Lexi says. “I’m rerouting the coordinates. Coordinates are 17,56-34-12 knot 65,56-22-75. Confirmed placement.”

“Recording,” Elba says.

And there is light.

Our brains start recording moments again, rebooted from our last jump. I half-hope this is some new scenario, a fresh start, but the chances of that are slim. We do these over and over again until we get them right. Because if we don’t get them right… well, shit, then we don’t exist.

We only remember our successes, never our failures. This helps with team morale, or so the psychs told us back in the training days, back when everything was burning, the whole world coming apart, and we got tapped to save it.

When they first started sending us back to secure a better future, the teams could remember every failure. It led to weariness and burnout; only the very stubborn or very stupid can stand living with the memory of compounded failure. Teams engaged in Operation Gray could endure more drops if we only remembered the good times. The successes. It kept us pushing forward.

For the failures, we had the logs. Our logs told us how many times we’d dropped in, and what we’d tried before. The trick, for me, was to pretend the log was from some other team. I pretended I was reading a report about somebody else who failed to complete the mission. I told myself my squad was coming in fresh to solve a problem someone else fucked up. Don’t think too hard about the fact that you were thinking the same thing every time you failed beforehand, or you’ll get stuck thinking about it, round and round, and then you’re not good for anything.

Trust me.

The light and shadow transform into our current coordinates in space and time. It’s the last month of autumn in the year we call 4600 BU (before us), known locally as the year 1214 Ab urbe condita, or 461 CE by some old alternate calendars. We are in the Western Roman Empire in what is known around here as Hispania, which will become Spain, then the European Alliance, then the Russian-US Federation, the Chinese-Russian Protectorate, then Europe again, and eventually, after several more handoffs, the province that in my time we call Malorian. I know this area, its future, because I was born sixteen kilometers north in the city of Madira. I know this coast because I will, more than three thousand years from now, walk upon these same beaches with my mothers, and raise a little orange flag during a parade celebrating the anniversary of Unification. My first visit here was also the first time I’d ever eaten a lemon, and the sharp, bitter taste is tied so closely with my memory of the coast that I taste lemon as we take in the sight of the sea just to our left.

A soft, salty wind blows in from over the Mediterranean. My bare toes sink into the sand. I bowl over and spit a mouthful of vomit. Beside me, Lexi has taken the jump worse. He’s lying on his side, frothing and seizing. Elba stumbles over to him and shoots him up with a stabilizing agent.

I pat at myself as the gear bags materialize around us.

“Got the football,” I say.

We’re nothing without the gear. Without the gear, we have to start the fuck over again. We’ve stumbled naked into camps before, no plasma, no flesh fixup, no antibacterial mesh, nothing, and for all our knowledge, we’re useless without those things. It wasn’t being dumb that killed so many of the people we’re here to save. It was simply not having access to what we did.

The wind is crisp. I shiver as I tear open the gooey sac protecting our gear. I make a guess at how all the clothes are supposed to go on; my AI still hasn’t completed the download for this mission. I lace on boots over sandy toes. The clothes part is always haphazard, never quite right. I don’t care what anyone says—it’s clear every time we jet into some other time that we’re aliens, strangers in a strange land. Go back far enough, you can claim godhood, but fewer people fall for that than the old stories would have you think. Better to say you were sent by a mutual acquaintance, a family friend.

I give another heave, spitting more bile, and blink as my AI completes the mission download. The AI’s presence is a warm, comforting one, sitting there in the back of my head, dutifully making connections faster than a non-augmented brain, and storing more information, more quickly, than a civilian. Four hundred years before I was born, AIs were considered separate entities, a different consciousness, like something that lived on its own. They stuck them into people’s heads and gave them names. But that drove far too many people mad. They tore off their own faces trying to get the fucker out. It was better if subjects saw the AI as a part of themselves, an enhancement to their own intelligence, instead of a separate entity.

The AI is how I knew this was former Visigoth territory, only recently brought to heel by the Western Roman Empire. I knew Majoram, the Western Roman Emperor, had been killed in the summer at the ripe old age of forty, and this being early autumn, there was a heated battle for the Emperor’s title still raging here in the west, led by Ricimer, the head of the army who’d had Majoram killed.

But the lofty milestones of history don’t prepare you much for the sort of work we do. All it does is provide greater context for what we’re walking into.

As we suit up, we don’t ask dumb questions like, Where is she? Where are we headed? The memories are already pouring in. We have other things to talk about.

“Lemon cake,” I say, continuing the last conversation we can remember; the one we were having after our last successful extraction, killing time before the next jump.

“Can’t talk about food,” Lexi says; he gags again.

“I miss cheeseburgers,” Elba says. “You remember those cheeseburgers at that diner back in… the woman on all the pills? That green vehicle? AI says the colloquial year was 1955.”

“Should have killed us,” I say. “You know how they processed meat back then?”

“Still mad they pulled us before I finished,” Elba says.

Lexi dry-heaves.

“Sorry,” Elba says.

I heft my pack; I’m the muscle on this trip—every trip—but you don’t want to carry stuff that looks too much like a weapon. We aren’t permitted to kill anyone anyway. You kill someone you aren’t supposed to, and you start over.

“We’re four to one,” Lexi says, knotting the laces of his sandals. He spits again.

I figure he’s referring to the fact that the log says our failure last time was because the subject bled out.

“Your mistake last time,” I say. “That’s four to two.”

“Bullshit,” he says. “She’d have died of an infection if she hadn’t bled out.”

“Who dropped the antibiotic mesh?” I say.

We are dressed in linen tunics, knee breeches, and long coats; the clothes aren’t well-worn enough to pass muster, even if they are the right cut for whatever class we’re supposed to be, and I’m sure they aren’t. When I ping the AI about that, I learn that we tried a more patrician style of clothing on our first drop, and got run out of town for it. This one apparently worked to get us past the settlement gatekeepers. I wasn’t going to argue with the AI’s memory.

“Up the dunes,” Elba says. “You can shit on each other and walk at the same time, right?”

“Memory serves, we sure can,” I say.

We walk up off the sandy beach. There’s not much I can recognize here, except the sea. The sea has washed up all sorts of detritus. There’s broken pottery and tiles, rusted bits of metal, tattered riggings, and refuse of all sorts. Far up the beach, I see what must be beach scavengers. They are headed in the other direction; I’m not sure if they witnessed our appearance on the beach.

Here and there are the jutting ruins of more sea trash, old shipwrecks, discarded implements, reminder that though this place is three thousand years before our time, the world here is already ancient. We’ve been farther back in time, much farther, but had found the results to be less precise. The farther back we go, the more complicated the mathematical models become. Too many variables. Turns out reverse-engineering a future by fiddling with the past can be… complicated. And often terribly messy. Careening through space-time wasn’t exactly what I’d had in mind when I signed up to serve and see Unification through. But here we are.

“If it’s the bleeding,” Lexi says, “I’ll prep the line first thing this time.”

On the other side of the dunes are a series of caves. The wind changes, and I catch the smell of the fires. Cave dwellers like these tend to choose these areas because they dislike the oppressive reach of the states. It was a wonder they weren’t slaves under some Roman landlord, but our records of Roman activity and expansion have never been exhaustive. Everything that is the past is fragmented. Our models do better tracking people through genetics—births and deaths—than across cultures and kingships and writs of sale on clay tablets that wash away over time. We can read the histories of our bodies in our blood—but less so the history of our cultures.

Our presence is noticed immediately by a young girl scouting on the rocks. She runs into the village for the headwoman. The AI tells me they are fisher folk, protected from engulfment by the wider body politic largely by geography. The able-bodied men are either dead or gone trawling, clinging to the edges of the beachhead, no doubt, worrying after fish.

“We’ve come for Junia Marcus,” Lexi says, “to assist in her time. We saw a storm swing low over the bay, and a two-headed gull led us here. I am Silvius Varis Alexander, freedman of Silvius. I knew Junia’s mother, Salia Marcus, freedwoman of Silvius. I’ve been sent here to assist her daughter for the kindness Salia Marcus once did for me.”

Since we’d had this conversation before, the language was already in the banks of the AI. By this time, most of Hispania was speaking Latin, though this dialect could better be described as Sergo Vulgaris, or common speech. I had a grim memory of speaking for six hours on a spur of rock outside a remote cabin in Antarctica, well after the Thaw, trying to get a young girl out there to speak to us so we could get some kind of idea how to untangle her language and figure out where the subject was holed up. She was far more delighted to speak to us the same way people had done from time immemorial, using gestures, exaggerated expressions, and sounds of encouragement and disapproval. Children were often much more accepting of strangers than their parents; children still believed in magic.

The headwoman is leery of us, but Lexi has a way of ingratiating himself. It’s his talent. And I know things are desperate inside the caves. Lexi is the one with the anthropology background; Elba came through via the medical team, and I signed on to be a frontline grunt, way back when. Or forward. Funny how shit turns out.

“She is young,” the headwoman says, finally, “it has been difficult. Your prayers are welcome, but men are not permitted within the birthing room.”

Lexi knits his brows. I blink, tapping into my AI to see if I’m remembering something wrong.

“Shit,” Elba says, in our squad patois, “that’s… new. How is that new?”

The AI confirms that the headwoman has never made this assertion before, not in all… four times we have attempted this mission. A wave of vertigo overcomes me.

“It’s a blip,” Lexi says. “A Crossroads.”

“Fuck,” I say.

I’ve heard of Crossroads before, read about them plenty, but never encountered one in all our drops. Crossroads are moments in time when your mission is rolling over concurrently with another team’s. As they rewrite the timeline ahead of or behind you, it writes over all of your prior work; it means your log isn’t going to be much good, because what happened last time technically happened on some other timeline. Listen, time travel’s fucking complicated. I don’t pretend to understand it, and I’m not here to lecture about it. All I know is what I got in training. All I know is the parameters we were working under just got rewritten.

“Grab Lexi’s gear,” Elba says to me. Then, to the headwoman, “The two of us will attend her. Time is of the essence. We have been warned that she is in grave danger.”

There is more back and forth, but the headwoman finally escorts us into the caves, just me and Elba now. I have Lexi’s gear, but that doesn’t give me much confidence. I’m supposed to be here to watch their backs while they do this shit. Not that I haven’t gotten myself elbow deep in blood and guts when I needed to, but I didn’t like having one squad member down.

We hear Junia before we see her. She is grunting and panting in the dim light of the headwoman’s lantern, surrounded by four other women. She does not scream, not yet. Beside her is a gory, deformed fetus, still and silent, half covered in a length of linen.

“Are we too late?” I say, because last time I never made it this far. Lexi took point, and we lost her.

“No,” Elba says, kneeling next to the nearest woman, gently placing a hand on her shoulder, murmuring, asking her to move aside.

“It’s the bleeding,” I say.

“You always say that,” Elba says. “I don’t want to do this one again. Especially if we’re at a Crossroads.”

“Prep the line,” I say. “Lexi was going to.”

Elba sighs, but she does it; can’t help doing it, because she knows as well as I that bleeding to death is how most of these women go. Blood loss, infection, or eclampsia are the top three causes of death for women during and immediately after childbirth. The children, well… there’s a lot more that can go wrong there. But it’s not as often that we’re here to save the children. Nine times out of ten, we’re here to save the mothers.

It’s the loss of these women, and often their children, that costs us our future.

Junia is young, maybe fifteen, which makes hemorrhage or obstruction more likely. Like the other women, she has fine black tattoos on her face, and hands covered in ash. I didn’t notice any of that on the headwoman, and I don’t have a memory of those tattoos from the AI. Another new twist, then. The world itself is literally shifting under our feet.

They have pulled her up into what I recognize as a birthing chair; there is blood and shit and piss and afterbirth collecting there, all mopped up with straw and piled over to one side. An older woman comes over and cleans it all away.

Depending on the society, and the time period, complications from childbirth killed roughly one half to one quarter of all women, with one’s chances of dying that way going up with every birth, if one survived the first. I knew from the records that this was the girl’s first birth, and that meant there were more variables. A woman who’d had one successful birth was more likely to have others. New mothers… well, that often ended poorly.

I hold out my arm.

“Not yet,” Elba says, and the wave of vertigo comes over me again. She blinks rapidly. The women around us shimmer, stutter-stop, like a bad projection. Two of them wink out altogether.

Junia wails, now, and the head of the second child begins to crown. Elba coaxes away the older woman. I shield what she’s doing. Elba makes a small cut in Junia’s perineum.

“We need you to push now,” Elba says.

Junia cries, “I have been pushing! I have pushed! What do you think I’m doing here?”

There is a woman at her left, a sister or cousin, who murmurs something in her ear, and together they breathe through the next set of contractions. Attending births the way we do feels obscene, often. We have appeared during a time of crisis, an intensely personal time, and often we come between a woman and her family. It’s not their fault, what lies ahead. If we could leave well enough alone—

The child’s head comes free; I see the cord wrapped around the throat, and I firm my jaw. Elba cuts again, and I wince. I have seen this enough that I should not care, but there is something intimately gory about birth that cannot be matched on a battlefield. It’s this knowledge that we are at the crux of life, where everything begins and ends. On a battlefield, most of what happens is endings.

Elba pulls the child free. He looks obscenely large, mostly due to the size of the head. She sets him on Junia’s belly. The cousin ties and cuts the cord. They want the placenta, but that’s not come yet. The placenta is when the bleeding will start, because it’s going to tear; that’s what the AI tells me, but how much has been altered since then?

The cousin is untangling the baby from the cord. She turns him upside down. Junia is exhausted, covered in sweat. She sags in the birthing chair, says, “Is he all right?”

I glance at Elba. The placenta is coming. I hold out my arm. She pulls the tubing from her pack and sets the line.

“What are you doing?” Junia says as Elba taps into her arm.

“You’re going to bleed,” Elba says. “I need to replace what you lose. It’s all right. We are friends of your mother’s.”

The cousin and the midwife—the only two women left in here after that last shimmer—are still attending the child, but the cousin turns as Junia flails.

“You’ll die if we don’t do this,” Elba says firmly. “Do you want to die here?”

“Save my baby,” Junia says.

I glance at Elba, but she does not meet my look. I know in that moment that we are no longer here for the baby. It’s strange, to see reports overwritten, to have our objective change in the space of a breath.

“We need to save you first,” Elba says. “Please be still. Do this for your own mother, a freedwoman. Would she want you to die this way?”

Junia gazes over at the child. The midwife has cleared his airways, and is massaging his chest. Elba sets the line in Junia’s arm.

I’m a universal donor, which is another reason I was put on this squad. They want a blood type like mine on hand. I guess you can be both, you know—the muscle and healer.

But as the blood leaves my body and enters Junia’s, and the bleeding begins, and Elba starts her work to still it, I, too, find myself gazing at the dead child. It would not have been difficult to save him. We have tubing we can snake down his throat; we have the gear to perform effective CPR. The AI tells me our mission has changed. I don’t know who it was that some other squad saved that changed it. Whoever they saved now meant our job was to leave this child to die, but it bothers me. Who are we to decide who lives and who dies?

I close my eyes, and I think of the future.

When it’s over, Elba and I pack up our things. They wrap the dead child in clean linen and the wailing begins. Elba has stopped the bleeding, and given Junia targeted antibiotics. She is stable. The AI indicates our mission is complete.

The headwoman leads us outside. Her lantern is different, made of paper instead of clay. As we step into the light, I see tents spread out all across the beach. The air feels different, too. The tents don’t look Roman at all. If I had to guess, I’d say they were Mongolian. But who’s to say, this far back? I hesitantly tap into the AI, and it tells me that yes, we are still at the same coordinates. The historical context, however, has changed. This is no longer Hispania, but Vestia, a newly independent country recently held by Persia. I had not noticed the change in language, but I suspect that was overwritten as well, as the world changed.

Lexi is sitting outside at the entrance to another cave, smoking a pipe and laughing uproariously with three women. He stands when he sees us. His clothes are different—a longer tunic, boots instead of sandals. I glance down and see I’m dressed the same.

“It’s been remarkable out here,” he says. “I’ve never witnessed a Crossroads event.”

“Let’s get back to the beach for extraction,” I say.

He seems confused at my lack of excitement. I’m tired. I palm an energy pack from the gear bag to help get my blood sugar back up.

Lexi asks for the details as we go back. Elba delivers them. I’m quiet. Finally, as we come within sight of the sea, he says, “Why does this one bother you, Asa?”

I shake my head.

“C’mon,” Lexi says. “I’ve seen you elbow deep in blood and afterbirth, untangling babies from malformed cords, cutting open dead women only to find dead babies inside, and spend an hour bringing those babies back. None of that shit bothered you.”

“Maybe it’s catching up with me.”

“Not likely,” Lexi says. “If it was going to catch up with you, it would’ve done so a long time ago.”

“How long you think we’ve been doing this?” I ask.

“Time is relative out here.”

It’s true. We can’t trust age. Each time we corporealize, we are made anew, copies of copies of copies. Those copies age only for the minutes, hours, or days we make landfall. Then they are simply reconstituted elsewhere, elsewhen.

“It all feels so arbitrary,” I say, gazing out at the wine-dark sea. “Who lives, who dies. We could save everyone, from every period. But we don’t. The Crossroads… We can see the consequences, if not with what we’ve done, then with what someone else has done just before us.”

“Don’t tell me you have a moral dilemma,” Elba says. She washes her hands in the sea, using the sand to scrub herself clean up to her elbows. “Everyone wants an easy answer, when it comes to morality.”

“Who are we to decide who lives and who dies?” Lexi says. “Yeah, I get that.”

“Who is every soldier, to decide that?” Elba says. “Soldiers have decided who lives and who dies forever. So have women like Junia, often. If that child lived, who’s to say they wouldn’t have sacrificed it to some god? The first one came out the way it did… they could have seen that as a bad sign. Humans have always decided who lives and who dies.”

“Now it’s an algorithm,” I say.

“Algorithms are made by people,” Elba says. “It’s the great moral dilemma. This is human, this is a life, this isn’t. Reality is, every culture has struggled with that since humans started fucking. Foreigners aren’t people, slaves aren’t people. Women aren’t people. Most of us were considered somebody’s property, same as goats or dogs, right up until the new world, right? And even then, you get people squabbling about who’s really equal, who really deserves access to a doctor, or lifesaving drugs, or food, or transit. ‘Who deserves it?’ they ask. What they’re really asking when they say it is, ‘Who’s really human?’ Who deserves to be treated as human? Who has worked hard enough, scarified enough, gotten lucky enough, to be treated like a human?”

“I just worry we’re fucking it up,” I say.

“Can’t think about that,” Lexi says.

I know that for a long time, in a lot of places, women were property, and so were the people they birthed. In other places, like this one, women’s bodies are collectively owned. It’s moral, here, for Junia to keep a pregnancy or end it based on what the community needs. And I get that moral order. I get it, when you’re just twelve people taking care of each other, surviving because of each other, out here at the edge of everything. Morals change as the needs of society change. Individual freedoms are a luxury of the modern age, of a collective dedication to providing people with the ability to exercise those freedoms. Here I am, becoming a fucking philosopher. That’s what this work gets you. Too much thinking.

“Morality is made up,” Elba says. “We’re making it up as we go along. There is no right answer, no infallible, logical truth when it comes to morality. Do the right thing in this moment. That’s all we have hope for.”

“She’s right,” Lexi says. “No easy answers. No future. I knew there was no best way, no perfect future. Every utopia is someone else’s dystopia. I worry too, though. You ever wonder if somebody else will get the tech while we’re gone? Maybe they already have, somebody who wants a different kind of future? You worry that just making this thing, assuming we’re benevolent… then finding out somebody wants something else, something worse?”

I stare out at the muddy horizon where it meets the sea. There’s a big black storm out there, all lit up from beneath by the rising sun. The sky is a bloody wound, beautiful.

“All the time,” I say. “I worry sometimes that it’s already happened. When was the last time we were back? We could be getting orders from anybody. I get that.”

“We have to keep going,” Elba says softly. “If we don’t create the future we’re from by re-engineering the past, we don’t exist. Unification never happens. Billions die. The Earth becomes a carbon-soaked sponge. We never see the stars. The sun eventually consumes all record of us. I’m a soldier first. I’ve always known I had a hand in who lives, who dies. This is no different.”

I track the fingers of the sun. The sun looks brighter, this far back in time. The moon would too, at night, because every year the moon moves about an inch and a half farther from the Earth. Go back far enough, and the moon is like a massive godly face in the sky, looming over everything. No wonder we worshipped it.

“I have to believe in our future,” Elba says. “I have to believe that as long as you and me and Lexi haven’t shuddered out of existence, there’s still a chance that future is being made out ahead of us. That’s all you can do, sometimes. Believe in the future.”

“If it was easy, everyone would do it,” Lexi says.

And then time stops.

There’s no transition between one time and the next, not that we’re ever aware of.

I wonder, often, if we are brought in to debrief, if anyone at all is left out there in our future to debrief. This deep into the operation I feel we are completely controlled by the algorithm.

Consciousness.

A spark.

A noise.

I breathe out as my body corporealizes around me. My vision blurs. Flashing colors. A dizzying blur of red. The smell of burning forests.