4,56 €

Mehr erfahren.

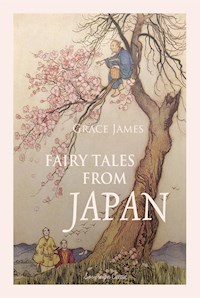

- Herausgeber: Sovereign

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Children's Classics

- Sprache: Englisch

Long ago, as I’ve heard tell, there dwelt at the temple of Morinji, in the Province of Kotsuke, a holy priest. Now there were three things about this reverend man. First, he was wrapped up in meditations and observances and forms and doctrines. He was a great one for the Sacred Sutras, and knew strange and mystical things. Then he had a fine exquisite taste of his own, and nothing pleased him so much as the ancient tea ceremony of the Cha-no-yu; and for the third thing about him, he knew both sides of a copper coin well enough and loved a bargain.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 323

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Grace James

Grace James

Fairy Tales from Japan

LONDON ∙ NEW YORK ∙ TORONTO ∙ SAO PAULO ∙ MOSCOW

PARIS ∙ MADRID ∙ BERLIN ∙ ROME ∙ MEXICO CITY ∙ MUMBAI ∙ SEOUL ∙ DOHA

TOKYO ∙ SYDNEY ∙ CAPE TOWN ∙ AUCKLAND ∙ BEIJING

New Edition

Published by Sovereign Classic

www.sovereignclassic.net

This Edition

First published in 2014

Copyright © 2014 Sovereign

Design and Artwork © 2014 www.urban-pic.co.uk

Images and Illustrations © 2014 Stocklibrary.org

All Rights Reserved.

Contents

GREEN WILLOW

THE FLUTE

THE TEA-KETTLE

THE PEONY LANTERN

THE SEA KING AND THE MAGIC JEWELS

THE GOOD THUNDER

THE BLACK BOWL

THE STAR LOVERS

HORAIZAN

REFLECTIONS

THE STORY OF SUSA, THE IMPETUOUS

THE WIND IN THE PINE TREE

FLOWER OF THE PEONY

THE MALLET

THE BELL OF DOJOJI

THE MAIDEN OF UNAI

THE ROBE OF FEATHERS

THE SINGING BIRD OF HEAVEN

THE COLD LADY

THE FIRE QUEST

A LEGEND OF KWANNON

THE ESPOUSAL OF THE RAT’S DAUGHTER

THE LAND OF YOMI

THE SPRING LOVER AND THE AUTUMN LOVER

THE STRANGE STORY OF THE GOLDEN COMB

THE JELLY-FISH TAKES A JOURNEY

URASHIMA

TAMAMO, THE FOX MAIDEN

MOMOTARO

THE MATSUYAMA MIRROR

BROKEN IMAGES

THE TONGUE-CUT SPARROW

THE NURSE

THE BEAUTIFUL DANCER OF YEDO

HANA-SAKA-JIJI

THE MOON MAIDEN

KARMA

THE SAD STORY OF THE YAOYA’S DAUGHTER

GREEN WILLOW

Tomodata, the young samurai, owed allegiance to the Lord of Noto. He was a soldier, a courtier, and a poet. He had a sweet voice and a beautiful face, a noble form and a very winning address. He was a graceful dancer, and excelled in every manly sport. He was wealthy and generous and kind. He was beloved by rich and by poor.

Now his daimyo, the Lord of Noto, wanted a man to undertake a mission of trust. He chose Tomodata, and called him to his presence.

“Are you loyal?” said the daimyo.

“My lord, you know it,” answered Tomodata.

“Do you love me, then?” asked the daimyo.

“Ay, my good lord,” said Tomodata, kneeling before him.

“Then carry my message,” said the daimyo. “Ride and do not spare your beast. Ride straight, and fear not the mountains nor the enemies’ country. Stay not for storm nor any other thing. Lose your life; but betray not your trust. Above all, do not look any maid between the eyes. Ride, and bring me word again quickly.”

Thus spoke the Lord of Noto.

So Tomodata got him to horse, and away he rode upon his quest. Obedient to his lord’s commands, he spared not his good beast. He rode straight, and was not afraid of the steep mountain passes nor of the enemies’ country. Ere he had been three days upon the road the autumn tempest burst, for it was the ninth month. Down poured the rain in a torrent. Tomodata bowed his head and rode on. The wind howled in the pine-tree branches. It blew a typhoon. The good horse trembled and could scarcely keep its feet, but Tomodata spoke to it and urged it on. His own cloak he drew close about him and held it so that it might not blow away, and in this wise he rode on.

The fierce storm swept away many a familiar landmark of the road, and buffeted the samurai so that he became weary almost to fainting. Noontide was as dark as twilight, twilight was as dark as night, and when night fell it was as black as the night of Yomi, where lost souls wander and cry. By this time Tomodata had lost his way in a wild, lonely place, where, as it seemed to him, no human soul inhabited. His horse could carry him no longer, and he wandered on foot through bogs and marshes, through rocky and thorny tracks, until he fell into deep despair.

“Alack!” he cried, “must I die in this wilderness and the quest of the Lord of Noto be unfulfilled?”

At this moment the great winds blew away the clouds of the sky, so that the moon shone very brightly forth, and by the sudden light Tomodata saw a little hill on his right hand. Upon the hill was a small thatched cottage, and before the cottage grew three green weeping-willow trees.

“Now, indeed, the gods be thanked!” said Tomodata, and he climbed the hill in no time. Light shone from the chinks of the cottage door, and smoke curled out of a hole in the roof. The three willow trees swayed and flung out their green streamers in the wind. Tomodata threw his horse’s rein over a branch of one of them, and called for admittance to the longed-for shelter.

At once the cottage door was opened by an old woman, very poorly but neatly clad.

“Who rides abroad upon such a night?” she asked, “and what wills he here?”

“I am a weary traveller, lost and benighted upon your lonely moor. My name is Tomodata. I am a samurai in the service of the Lord of Noto, upon whose business I ride. Show me hospitality for the love of the gods. I crave food and shelter for myself and my horse.”

As the young man stood speaking the water streamed from his garments. He reeled a little, and put out a hand to hold on by the side-post of the door.

“Come in, come in, young sir!” cried the old woman, full of pity. “Come in to the warm fire. You are very welcome. We have but coarse fare to offer, but it shall be set before you with great good-will. As to your horse, I see you have delivered him to my daughter; he is in good hands.”

At this Tomodata turned sharply round. Just behind him, in the dim light, stood a very young girl with the horse’s rein thrown over her arm. Her garments were blown about and her long loose hair streamed out upon the wind. The samurai wondered how she had come there. Then the old woman drew him into the cottage and shut the door. Before the fire sat the good man of the house, and the two old people did the very best they could for Tomodata. They gave him dry garments, comforted him with hot rice wine, and quickly prepared a good supper for him.

Presently the daughter of the house came in, and retired behind a screen to comb her hair and to dress afresh. Then she came forth to wait upon him. She wore a blue robe of homespun cotton. Her feet were bare. Her hair was not tied nor confined in any way, but lay along her smooth cheeks, and hung, straight and long and black, to her very knees. She was slender and graceful. Tomodata judged her to be about fifteen years old, and knew well that she was the fairest maiden he had ever seen.

At length she knelt at his side to pour wine into his cup. She held the wine-bottle in two hands and bent her head. Tomodata turned to look at her. When she had made an end of pouring the wine and had set down the bottle, their glances met, and Tomodata looked at her full between the eyes, for he forgot altogether the warning of his daimyo, the Lord of Noto.

“Maiden,” he said, “what is your name?”

She answered: “They call me the Green Willow.”

“The dearest name on earth,” he said, and again he looked her between the eyes. And because he looked so long her face grew rosy red, from chin to forehead, and though she smiled her eyes filled with tears.

Ah me, for the Lord of Noto’s quest!

Then Tomodata made this little song:

“Long-haired maiden, do you know

That with the red dawn I must go?

Do you wish me far away?

Cruel long-haired maiden, say—

Long-haired maiden, if you know

That with the red dawn I must go,

Why, oh why, do you blush so?”

And the maiden, the Green Willow, answered:

“The dawn comes if I will or no;

Never leave me, never go.

My sleeve shall hide the blush away.

The dawn comes if I will or no;

Never leave me, never go.

Lord, I lift my long sleeve so....”

“Oh, Green Willow, Green Willow ...” sighed Tomodata.

That night he lay before the fire—still, but with wide eyes, for no sleep came to him though he was weary. He was sick for love of the Green Willow. Yet by the rules of his service he was bound in honour to think of no such thing. Moreover, he had the quest of the Lord of Noto that lay heavy on his heart, and he longed to keep truth and loyalty.

At the first peep of day he rose up. He looked upon the kind old man who had been his host, and left a purse of gold at his side as he slept. The maiden and her mother lay behind the screen.

Tomodata saddled and bridled his horse, and mounting, rode slowly away through the mist of the early morning. The storm was quite over and it was as still as Paradise. The green grass and the leaves shone with the wet. The sky was clear, and the path very bright with autumn flowers; but Tomodata was sad.

When the sunlight streamed across his saddlebow, “Ah, Green Willow, Green Willow,” he sighed; and at noontide it was “Green Willow, Green Willow”; and “Green Willow, Green Willow,” when the twilight fell. That night he lay in a deserted shrine, and the place was so holy that in spite of all he slept from midnight till the dawn. Then he rose, having it in his mind to wash himself in a cold stream that flowed near by, so as to go refreshed upon his journey; but he was stopped upon the shrine’s threshold. There lay the Green Willow, prone upon the ground. A slender thing she lay, face downwards, with her black hair flung about her. She lifted a hand and held Tomodata by the sleeve. “My lord, my lord,” she said, and fell to sobbing piteously.

He took her in his arms without a word, and soon he set her on his horse before him, and together they rode the livelong day. It was little they recked of the road they went, for all the while they looked into each other’s eyes. The heat and the cold were nothing to them. They felt not the sun nor the rain; of truth or falsehood they thought nothing at all; nor of filial piety, nor of the Lord of Noto’s quest, nor of honour nor plighted word. They knew but the one thing. Alas, for the ways of love!

At last they came to an unknown city, where they stayed. Tomodata carried gold and jewels in his girdle, so they found a house built of white wood, spread with sweet white mats. In every dim room there could be heard the sound of the garden waterfall, whilst the swallow flitted across and across the paper lattice. Here they dwelt, knowing but the one thing. Here they dwelt three years of happy days, and for Tomodata and the Green Willow the years were like garlands of sweet flowers.

In the autumn of the third year it chanced that the two of them went forth into the garden at dusk, for they had a wish to see the round moon rise; and as they watched, the Green Willow began to shake and shiver.

“My dear,” said Tomodata, “you shake and shiver; and it is no wonder, the night wind is chill. Come in.” And he put his arm around her.

At this she gave a long and pitiful cry, very loud and full of agony, and when she had uttered the cry she failed, and dropped her head upon her love’s breast.

“Tomodata,” she whispered, “say a prayer for me; I die.”

“Oh, say not so, my sweet, my sweet! You are but weary; you are faint.”

He carried her to the stream’s side, where the iris grew like swords, and the lotus-leaves like shields, and laved her forehead with water. He said: “What is it, my dear? Look up and live.”

“The tree,” she moaned, “the tree ... they have cut down my tree. Remember the Green Willow.”

With that she slipped, as it seemed, from his arms to his feet; and he, casting himself upon the ground, found only silken garments, bright coloured, warm and sweet, and straw sandals, scarlet-thonged.

In after years, when Tomodata was a holy man, he travelled from shrine to shrine, painfully upon his feet, and acquired much merit.

Once, at nightfall, he found himself upon a lonely moor. On his right hand he beheld a little hill, and on it the sad ruins of a poor thatched cottage. The door swung to and fro with broken latch and creaking hinge. Before it stood three old stumps of willow trees that had long since been cut down. Tomodata stood for a long time still and silent. Then he sang gently to himself:

“Long-haired maiden, do you know

That with the red dawn I must go?

Do you wish me far away?

Cruel long-haired maiden, say—

Long-haired maiden, if you know

That with the red dawn I must go,

Why, oh why, do you blush so?”

“Ah, foolish song! The gods forgive me.... I should have recited the Holy Sutra for the Dead,” said Tomodata.

THE FLUTE

Long since, there lived in Yedo a gentleman of good lineage and very honest conversation. His wife was a gentle and loving lady. To his secret grief, she bore him no sons. But a daughter she did give him, whom they called O’Yoné, which, being interpreted, is “Rice in the ear.” Each of them loved this child more than life, and guarded her as the apple of their eye. And the child grew up red and white, and long-eyed, straight and slender as the green bamboo.

When O’Yoné was twelve years old, her mother drooped with the fall of the year, sickened, and pined, and ere the red had faded from the leaves of the maples she was dead and shrouded and laid in the earth. The husband was wild in his grief. He cried aloud, he beat his breast, he lay upon the ground and refused comfort, and for days he neither broke his fast nor slept. The child was quite silent.

Time passed by. The man perforce went about his business. The snows of winter fell and covered his wife’s grave. The beaten pathway from his house to the dwelling of the dead was snow also, undisturbed save for the faint prints of a child’s sandalled feet. In the spring-time he girded up his robe and went forth to see the cherry blossom, making merry enough, and writing a poem upon gilded paper, which he hung to a cherry-tree branch to flutter in the wind. The poem was in praise of the spring and of saké. Later, he planted the orange lily of forgetfulness, and thought of his wife no more. But the child remembered.

Before the year was out he brought a new bride home, a woman with a fair face and a black heart. But the man, poor fool, was happy, and commended his child to her, and believed that all was well.

Now because her father loved O’Yoné, her stepmother hated her with a jealous and deadly hatred, and every day she dealt cruelly by the child, whose gentle ways and patience only angered her the more. But because of her father’s presence she did not dare to do O’Yoné any great ill; therefore she waited, biding her time. The poor child passed her days and her nights in torment and horrible fear. But of these things she said not a word to her father. Such is the manner of children.

Now, after some time, it chanced that the man was called away by his business to a distant city. Kioto was the name of the city, and from Yedo it is many days’ journey on foot or on horseback. Howbeit, go the man needs must, and stay there three moons or more. Therefore he made ready, and equipped himself, and his servants that were to go with him, with all things needful; and so came to the last night before his departure, which was to be very early in the morning.

He called O’Yoné to him and said: “Come here, then, my dear little daughter.” So O’Yoné went and knelt before him.

“What gift shall I bring you home from Kioto?” he said.

But she hung her head and did not answer.

“Answer, then, rude little one,” he bade her. “Shall it be a golden fan, or a roll of silk, or a new obi of red brocade, or a great battledore with images upon it and many light-feathered shuttlecocks?”

Then she burst into bitter weeping, and he took her upon his knees to soothe her. But she hid her face with her sleeves and cried as if her heart would break. And, “O father, father, father,” she said, “do not go away—do not go away!”

“But, my sweet, I needs must,” he answered, “and soon I shall be back—so soon, scarcely it will seem that I am gone, when I shall be here again with fair gifts in my hand.”

“Father, take me with you,” she said.

“Alas, what a great way for a little girl! Will you walk on your feet, my little pilgrim, or mount a pack-horse? And how would you fare in the inns of Kioto? Nay, my dear, stay; it is but for a little time, and your kind mother will be with you.”

She shuddered in his arms.

“Father, if you go, you will never see me more.”

Then the father felt a sudden chill about his heart, that gave him pause. But he would not heed it. What! Must he, a strong man grown, be swayed by a child’s fancies? He put O’Yoné gently from him, and she slipped away as silently as a shadow.

But in the morning she came to him before sunrise with a little flute in her hand, fashioned of bamboo and smoothly polished. “I made it myself,” she said, “from a bamboo in the grove that is behind our garden. I made it for you. As you cannot take me with you, take the little flute, honourable father. Play on it sometimes, if you will, and think of me.” Then she wrapped it in a handkerchief of white silk, lined with scarlet, and wound a scarlet cord about it, and gave it to her father, who put it in his sleeve. After this he departed and went his way, taking the road to Kioto. As he went he looked back thrice, and beheld his child, standing at the gate, looking after him. Then the road turned and he saw her no more.

The city of Kioto was passing great and beautiful, and so the father of O’Yoné found it. And what with his business during the day, which sped very well, and his pleasure in the evening, and his sound sleep at night, the time passed merrily, and small thought he gave to Yedo, to his home, or to his child. Two moons passed, and three, and he made no plans for return.

One evening he was making ready to go forth to a great supper of his friends, and as he searched in his chest for certain brave silken hakama which he intended to wear as an honour to the feast, he came upon the little flute, which had lain hidden all this time in the sleeve of his travelling dress. He drew it forth from its red and white handkerchief, and as he did so, felt strangely cold with an icy chill that crept about his heart. He hung over the live charcoal of the hibachi as one in a dream. He put the flute to his lips, when there came from it a long-drawn wail.

He dropped it hastily upon the mats and clapped his hands for his servant, and told him he would not go forth that night. He was not well, he would be alone. After a long time he reached out his hand for the flute. Again that long, melancholy cry. He shook from head to foot, but he blew into the flute. “Come back to Yedo ... come back to Yedo.... Father! Father!” The quavering childish voice rose to a shriek and then broke.

A horrible foreboding now took possession of the man, and he was as one beside himself. He flung himself from the house and from the city, and journeyed day and night, denying himself sleep and food. So pale was he and wild that the people deemed him a madman and fled from him, or pitied him as the afflicted of the gods. At last he came to his journey’s end, travel-stained from head to heel, with bleeding feet and half-dead of weariness.

His wife met him in the gate.

He said: “Where is the child?”

“The child...?” she answered.

“Ay, the child—my child ... where is she?” he cried in an agony.

The woman laughed: “Nay, my lord, how should I know? She is within at her books, or she is in the garden, or she is asleep, or mayhap she has gone forth with her playmates, or ...”

He said: “Enough; no more of this. Come, where is my child?”

Then she was afraid. And, “In the Bamboo Grove,” she said, looking at him with wide eyes.

There the man ran, and sought O’Yoné among the green stems of the bamboos. But he did not find her. He called, “Yoné! Yoné!” and again, “Yoné! Yoné!” But he had no answer; only the wind sighed in the dry bamboo leaves. Then he felt in his sleeve and brought forth the little flute, and very tenderly put it to his lips. There was a faint sighing sound. Then a voice spoke, thin and pitiful:

“Father, dear father, my wicked stepmother killed me. Three moons since she killed me. She buried me in the clearing of the Bamboo Grove. You may find my bones. As for me, you will never see me any more—you will never see me more....”

With his own two-handed sword the man did justice, and slew his wicked wife, avenging the death of his innocent child. Then he dressed himself in coarse white raiment, with a great rice-straw hat that shadowed his face. And he took a staff and a straw rain-coat and bound sandals on his feet, and thus he set forth upon a pilgrimage to the holy places of Japan.

And he carried the little flute with him, in a fold of his garment, upon his breast.

THE TEA-KETTLE

Long ago, as I’ve heard tell, there dwelt at the temple of Morinji, in the Province of Kotsuke, a holy priest.

Now there were three things about this reverend man. First, he was wrapped up in meditations and observances and forms and doctrines. He was a great one for the Sacred Sutras, and knew strange and mystical things. Then he had a fine exquisite taste of his own, and nothing pleased him so much as the ancient tea ceremony of the Cha-no-yu; and for the third thing about him, he knew both sides of a copper coin well enough and loved a bargain.

None so pleased as he when he happened upon an ancient tea-kettle, lying rusty and dirty and half-forgotten in a corner of a poor shop in a back street of his town.

“An ugly bit of old metal,” says the holy man to the shopkeeper; “but it will do well enough to boil my humble drop of water of an evening. I’ll give you three rin for it.” This he did and took the kettle home, rejoicing; for it was of bronze, fine work, the very thing for the Cha-no-yu.

A novice cleaned and scoured the tea-kettle, and it came out as pretty as you please. The priest turned it this way and that, and upside down, looked into it, tapped it with his finger-nail. He smiled. “A bargain,” he cried, “a bargain!” and rubbed his hands. He set the kettle upon a box covered over with a purple cloth, and looked at it so long that first he was fain to rub his eyes many times, and then to close them altogether. His head dropped forward and he slept.

And then, believe me, the wonderful thing happened. The tea-kettle moved, though no hand was near it. A hairy head, with two bright eyes, looked out of the spout. The lid jumped up and down. Four brown and hairy paws appeared, and a fine bushy tail. In a minute the kettle was down from the box and going round and round looking at things.

“A very comfortable room, to be sure,” says the tea-kettle.

Pleased enough to find itself so well lodged, it soon began to dance and to caper nimbly and to sing at the top of its voice. Three or four novices were studying in the next room. “The old man is lively,” they said; “only hark to him. What can he be at?” And they laughed in their sleeves.

Heaven’s mercy, the noise that the tea-kettle made! Bang! bang! Thud! thud! thud!

The novices soon stopped laughing. One of them slid aside the kara-kami and peeped through.

“Arah, the devil and all’s in it!” he cried. “Here’s the master’s old tea-kettle turned into a sort of a badger. The gods protect us from witchcraft, or for certain we shall be lost!”

“And I scoured it not an hour since,” said another novice, and he fell to reciting the Holy Sutras on his knees.

A third laughed. “I’m for a nearer view of the hobgoblin,” he said.

So the lot of them left their books in a twinkling, and gave chase to the tea-kettle to catch it. But could they come up with the tea-kettle? Not a bit of it. It danced and it leapt and it flew up into the air. The novices rushed here and there, slipping upon the mats. They grew hot. They grew breathless.

“Ha, ha! Ha, ha!” laughed the tea-kettle; and “Catch me if you can!” laughed the wonderful tea-kettle.

Presently the priest awoke, all rosy, the holy man.

“And what’s the meaning of this racket,” he says, “disturbing me at my holy meditations and all?”

“Master, master,” cry the novices, panting and mopping their brows, “your tea-kettle is bewitched. It was a badger, no less. And the dance it has been giving us, you’d never believe!”

“Stuff and nonsense,” says the priest; “bewitched? Not a bit of it. There it rests on its box, good quiet thing, just where I put it.”

Sure enough, so it did, looking as hard and cold and innocent as you please. There was not a hair of a badger near it. It was the novices that looked foolish.

“A likely story indeed,” says the priest. “I have heard of the pestle that took wings to itself and flew away, parting company with the mortar. That is easily to be understood by any man. But a kettle that turned into a badger—no, no! To your books, my sons, and pray to be preserved from the perils of illusion.”

That very night the holy man filled the kettle with water from the spring and set it on the hibachi to boil for his cup of tea. When the water began to boil—

“Ai! Ai!” the kettle cried; “Ai! Ai! The heat of the Great Hell!” And it lost no time at all, but hopped off the fire as quick as you please.

“Sorcery!” cried the priest. “Black magic! A devil! A devil! A devil! Mercy on me! Help! Help! Help!” He was frightened out of his wits, the dear good man. All the novices came running to see what was the matter.

“The tea-kettle is bewitched,” he gasped; “it was a badger, assuredly it was a badger ... it both speaks and leaps about the room.”

“Nay, master,” said a novice, “see where it rests upon its box, good quiet thing.”

And sure enough, so it did.

“Most reverend sir,” said the novice, “let us all pray to be preserved from the perils of illusion.”

The priest sold the tea-kettle to a tinker and got for it twenty copper coins.

“It’s a mighty fine bit of bronze,” says the priest. “Mind, I’m giving it away to you, I’m sure I cannot tell what for.” Ah, he was the one for a bargain! The tinker was a happy man and carried home the kettle. He turned it this way and that, and upside down, and looked into it.

“A pretty piece,” says the tinker; “a very good bargain.” And when he went to bed that night he put the kettle by him, to see it first thing in the morning.

He awoke at midnight and fell to looking at the kettle by the bright light of the moon.

Presently it moved, though there was no hand near it.

“Strange,” said the tinker; but he was a man who took things as they came.

A hairy head, with two bright eyes, looked out of the kettle’s spout. The lid jumped up and down. Four brown and hairy paws appeared, and a fine bushy tail. It came quite close to the tinker and laid a paw upon him.

“Well?” says the tinker.

“I am not wicked,” says the tea-kettle.

“No,” says the tinker.

“But I like to be well treated. I am a badger tea-kettle.”

“So it seems,” says the tinker.

“At the temple they called me names, and beat me and set me on the fire. I couldn’t stand it, you know.”

“I like your spirit,” says the tinker.

“I think I shall settle down with you.”

“Shall I keep you in a lacquer box?” says the tinker.

“Not a bit of it, keep me with you; let us have a talk now and again. I am very fond of a pipe. I like rice to eat, and beans and sweet things.”

“A cup of saké sometimes?” says the tinker.

“Well, yes, now you mention it.”

“I’m willing,” says the tinker.

“Thank you kindly,” says the tea-kettle; “and, as a beginning, would you object to my sharing your bed? The night has turned a little chilly.”

“Not the least in the world,” says the tinker.

The tinker and the tea-kettle became the best of friends. They ate and talked together. The kettle knew a thing or two and was very good company.

One day: “Are you poor?” says the kettle.

“Yes,” says the tinker, “middling poor.”

“Well, I have a happy thought. For a tea-kettle, I am out-of-the-way—really very accomplished.”

“I believe you,” says the tinker.

“My name is Bumbuku-Chagama; I am the very prince of Badger Tea-Kettles.”

“Your servant, my lord,” says the tinker.

“If you’ll take my advice,” says the tea-kettle, “you’ll carry me round as a show; I really am out-of-the-way, and it’s my opinion you’d make a mint of money.”

“That would be hard work for you, my dear Bumbuku,” says the tinker.

“Not at all; let us start forthwith,” says the tea-kettle.

So they did. The tinker bought hangings for a theatre, and he called the show Bumbuku-Chagama. How the people flocked to see the fun! For the wonderful and most accomplished tea-kettle danced and sang, and walked the tight rope as to the manner born. It played such tricks and had such droll ways that the people laughed till their sides ached. It was a treat to see the tea-kettle bow as gracefully as a lord and thank the people for their patience.

The Bumbuku-Chagama was the talk of the country-side, and all the gentry came to see it as well as the commonalty. As for the tinker, he waved a fan and took the money. You may believe that he grew fat and rich. He even went to Court, where the great ladies and the royal princesses made much of the wonderful tea-kettle.

At last the tinker retired from business, and to him the tea-kettle came with tears in its bright eyes.

“I’m much afraid it’s time to leave you,” it says.

“Now, don’t say that, Bumbuku, dear,” says the tinker. “We’ll be so happy together now we are rich.”

“I’ve come to the end of my time,” says the tea-kettle. “You’ll not see old Bumbuku any more; henceforth I shall be an ordinary kettle, nothing more or less.”

“Oh, my dear Bumbuku, what shall I do?” cried the poor tinker in tears.

“I think I should like to be given to the temple of Morinji, as a very sacred treasure,” says the tea-kettle.

It never spoke or moved again. So the tinker presented it as a very sacred treasure to the temple, and the half of his wealth with it.

And the tea-kettle was held in wondrous fame for many a long year. Some persons even worshipped it as a saint.

THE PEONY LANTERN

In Yedo there dwelt a samurai called Hagiwara. He was a samurai of the hatamoto, which is of all the ranks of samurai the most honourable. He possessed a noble figure and a very beautiful face, and was beloved of many a lady of Yedo, both openly and in secret. For himself, being yet very young, his thoughts turned to pleasure rather than to love, and morning, noon and night he was wont to disport himself with the gay youth of the city. He was the prince and leader of joyous revels within doors and without, and would often parade the streets for long together with bands of his boon companions.

One bright and wintry day during the Festival of the New Year he found himself with a company of laughing youths and maidens playing at battledore and shuttlecock. He had wandered far away from his own quarter of the city, and was now in a suburb quite the other side of Yedo, where the streets were empty, more or less, and the quiet houses stood in gardens. Hagiwara wielded his heavy battledore with great skill and grace, catching the gilded shuttlecock and tossing it lightly into the air; but at length with a careless or an ill-judged stroke, he sent it flying over the heads of the players, and over the bamboo fence of a garden near by. Immediately he started after it. Then his companions cried, “Stay, Hagiwara; here we have more than a dozen shuttlecocks.”

“Nay,” he said, “but this was dove-coloured and gilded.”

“Foolish one!” answered his friends; “here we have six shuttlecocks all dove-coloured and gilded.”

But he paid them no heed, for he had become full of a very strange desire for the shuttlecock he had lost. He scaled the bamboo fence and dropped into the garden which was upon the farther side. Now he had marked the very spot where the shuttlecock should have fallen, but it was not there; so he searched along the foot of the bamboo fence—but no, he could not find it. Up and down he went, beating the bushes with his battledore, his eyes on the ground, drawing breath heavily as if he had lost his dearest treasure. His friends called him, but he did not come, and they grew tired and went to their own homes. The light of day began to fail. Hagiwara, the samurai, looked up and saw a girl standing a few yards away from him. She beckoned him with her right hand, and in her left she held a gilded shuttlecock with dove-coloured feathers.

The samurai shouted joyfully and ran forward. Then the girl drew away from him, still beckoning him with the right hand. The shuttlecock lured him, and he followed. So they went, the two of them, till they came to the house that was in the garden, and three stone steps that led up to it. Beside the lowest step there grew a plum tree in blossom, and upon the highest step there stood a fair and very young lady. She was most splendidly attired in robes of high festival. Her kimono was of water-blue silk, with sleeves of ceremony so long that they touched the ground; her under-dress was scarlet, and her great girdle of brocade was stiff and heavy with gold. In her hair were pins of gold and tortoiseshell and coral.

When Hagiwara saw the lady, he knelt down forthwith and made her due obeisance, till his forehead touched the ground.

Then the lady spoke, smiling with pleasure like a child. “Come into my house, Hagiwara Sama, samurai of the hatamoto. I am O’Tsuyu, the Lady of the Morning Dew. My dear handmaiden, O’Yoné, has brought you to me. Come in, Hagiwara Sama, samurai of the hatamoto; for indeed I am glad to see you, and happy is this hour.”

So the samurai went in, and they brought him to a room of ten mats, where they entertained him; for the Lady of the Morning Dew danced before him in the ancient manner, whilst O’Yoné, the handmaiden, beat upon a small scarlet-tasselled drum.

Afterwards they set food before him, the red rice of the festival and sweet warm wine, and he ate and drank of the food they gave him.

It was dark night when Hagiwara took his leave. “Come again, honourable lord, come again,” said O’Yoné the handmaiden.

“Yea, lord, you needs must come,” whispered the Lady of the Morning Dew.

The samurai laughed. “And if I do not come?” he said mockingly. “What if I do not come?”

The lady stiffened, and her child’s face grew grey, but she laid her hand upon Hagiwara’s shoulder.

“Then,” she said, “it will be death, lord. Death it will be for you and for me. There is no other way.” O’Yoné shuddered and hid her eyes with her sleeve.

The samurai went out into the night, being very much afraid.

Long, long he sought for his home and could not find it, wandering in the black darkness from end to end of the sleeping city. When at last he reached his familiar door the late dawn was almost come, and wearily he threw himself upon his bed. Then he laughed. “After all, I have left behind me my shuttlecock,” said Hagiwara the samurai.