45,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

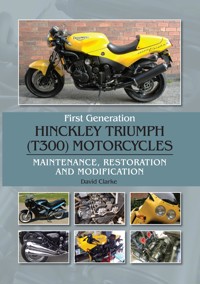

The early Hinckley Triumphs produced from 1991 to 2004 – Trophy, Daytona, Trident, Trident Sprint, Tiger, Speed Triple, Adventurer, Thunderbird – were designed and manufactured using a modular concept. This assists in the sharing of components across the range of bikes, which was useful with the restricted availability of spare parts. With over 725 colour photographs, this book provides helpful guidance on keeping your bike on the road, including a discussion of the models produced and their modular design; identifying common problems and how to address them. There is a comprehensive guide to maintenance, including the tools required and details of restoration, modification and upgrades, from changing the exhaust to fabricating swing arms. There is a useful list of suppliers for both new and reconditioned parts, as well as specialist service providers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 400

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

First published in 2021 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© David Clarke 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 944 0

Disclaimer Safety is of the utmost importance in every aspect of an automotive workshop. The practical procedures and the tools and equipment used in automotive workshops are potentially dangerous. Tools should be used in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s recommended procedures and current health and safety regulations. The author and publisher cannot accept responsibility for any accident or injury caused by following the advice given in this book.

Triumph Motorcycles do not endorse or support the switching of parts between bikes they were not originally intended for, or the modifying of bikes beyond their original purpose, so any maintenance or changes you make as a result of reading this book are not the responsibility of Triumph Motorcycles, the author or the publisher.

Cover design by Maggie Mellett

contents

acknowledgements

introduction

1the T300 range and the start of Hinckley Triumph

2modular design

3essential tools and equipment

4common problems

5maintenance and care of the bike

6restoration

7upgrades and using non-Triumph parts

8building modified bikes

9more extensive modifications

appendix I parts supply

appendix II specialized services

appendix III Triumph T300 paint colours by model

appendix IV Triumph colours and paintcodes

appendix V carburettor jetting sizes

appendix VI wheels and tyre sizes

index

acknowledgements

This book would have been impossible without the help and support of a number of T300 riders and friends. Postings on the various Facebook Triumph groups (T300, Mk 1 Speed Triple, Modified Hinckley Triumphs, Daytona and so on) have also been enlightening. Friends who have contributed include Gordon Smith (who also took some photographs used in the book), Ivan from National Triumph (whose knowledge of T300 parts is unparalleled), Mark Gaylard (again supplying many photographs and some text), Paul Messenger, Sean Symonds, Trevor Smith of Sprint Manufacturing, Cavan Holden, Christian Forward, Bob Cornforth, Denis Fitch, Chris Foxley, Paul Humphreys, Paul Barnett and Phil Ogden. I also thank my wife, Glenis, for proofreading and supporting me in my passion for T300 motorcycles.

I make no apology for using text in various sections in the book supplied by Mark Gaylard, Gordon Smith and Paul Barnett as they know what they are doing! I would have liked to use official Triumph material but that was not possible.

Lastly, if you plan to do any major work on the engine and carburettors, then go on one of the two-day courses run by T300 guru Clive Wood in Lincolnshire. These are normally run over a weekend in the winter months and cover the major jobs on an engine, particularly stripping an engine down for a sprag clutch change. The course will give you an insight into how it’s done and the confidence to go ahead. Clive has been servicing, building, modifying and racing T300s since 1991 and is extremely knowledgeable. This course is a must have if you want to learn more about the T300 engine. Clive can also service and repair your bike.

introduction

I have been a first generation Hinckley Triumph owner since 1997, when I bought my first new bike, a Triumph Sprint Sports; this has been followed by three different Mk 1 Speed Triples (one Black, one Racing Yellow and one an ex-Speed Triple Challenge race bike), a Daytona Super 3 and a Daytona 900, which I turned into a café racer using the excellent kit from CRK (Café Racer Kits). I still have the first Speed Triple in the rare Racing Yellow, which I bought back in 2010 and am keeping it in original condition while doing a rolling restoration on it. I also have the Café Racer along with a more modern 2008 Triumph Thruxton, which has been heavily customized.

I had carried out basic maintenance such as oil/filter changes, but when I acquired a 1994 ex-Speed Triple Challenge bike that was in a very poor condition (despite only having 3,200km/2,000 miles on the clock) as it had been stored for many years, I was faced with moving to a new level of restoration and maintenance. The bike was complete with all the original racing parts, so, after taking a deep breath, I commenced of a full rebuild. I stripped it down to the frame and either refurbished or replaced parts as required. In the course of the restoration, I replaced the swing arm, had the engine rebuilt (by Triumph guru Chris Foxley) and refurbished/overhauled lots of parts – brake calipers, carburettors, forks, rear shock absorber (it was fitted with a Proflex as authorized by the race series and rebuildable) – including re-powder coating many of them. Consumables like the chain and sprockets, air filter and spark plugs were replaced while servicing the bike.

This was the first time I had stripped a bike down completely but it was with the assistance of friends who were also Triumph enthusiasts and who gave me plenty of help and advice. What was very helpful was using a small digital camera to photograph everything at every stage as I dismantled each part before putting the bits into a bag marked up with a description. This saved the day more than once, as there was often a long time gap between taking things apart and reassembling them.

Researching the Speed Triple Challenge and the Mk 1 Speed Triple became a bit of an obsession with me after working on these early Triumphs, though I don’t consider myself a mechanic and this book is not intended to replace the Triumph factory workshop manual. With the right tools, and the tips and hints in this book, however, you should be able to maintain better your T300 and know your way round the main components and which parts will fit from one model into another. I have also included a number of bikes that have been modified to illustrate the potential of the interchangeable parts, as well as given details of parts suppliers and individuals who can help where you are not confident your own skills (or tools) can do what you require. All the suppliers I mention are ones I have used over the years or are known to be purveyors of the right parts and services.

Before starting any job, have a look at the official Triumph workshop manual (supplemented by the excellent Haynes manual #2162, now revised) and check that you have the correct tools and have ordered any parts required. Read the relevant section in the manual to familiarize yourself with the sequence and logic behind the operation. You can also post questions on the appropriate Triumph Facebook or other internet groups. If you are in any doubt, commission an independent Triumph mechanic to do the job. You can also use a Triumph dealer for work on your T300, but this can prove to be expensive, and lots of dealerships no longer have mechanics that are familiar with the T300 range.

Structuring this book proved to be a challenge. On the assumption that few people will read from cover to cover, some information is duplicated in different sections.

While I have tried to include as many of the jobs required to maintain your T300 as possible, I have not included a blow-by-blow account for everything. So, for example, I have provided some hints and tips on changing the sprag clutch, but not a detailed breakdown or photos of the work.

The writing of this book was inspired by Mark Gaylard, who created a website (mottleybiker.com) that covers some of the maintenance tasks outlined in this book, but I have hopefully taken this a stage further and also detailed the parts that are interchangeable between models. Mark generously allowed me to use some of the text from his website in this book. Having sections describing how to do various jobs was straightforward, but deciding to include upgrades and modifications to the models has opened whole new vistas – there are some incredible bikes out there!

1

the T300 range and the start of Hinckley Triumph

This section is a summary of what I included in the companion volume to this book, Hinckley Triumph: The First Generation, which was published in 2012 (and still available from Crowood). This covers each model in detail with all changes and revisions identified as well as the colours used on each bike and details how John Bloor set up the company and created a modern high-tech motor cycle company from nothing except the brand name.

There seemed little point in restating the contents of that first book, so the following is a summary and an update since I finished the previous title.

NAMING CONVENTION

In this book, I refer to ‘T300’ throughout as T3XX was the code used by Triumph for the range of bikes covered by this book and constitutes the first generation of Hinckley-built motorcycles. So the first machine, the Daytona 750, was given the code TC331 and the numbers increased up to TC399 for the Adventurer. Triumph then went back in the number sequence and used TC301 for the Speed Triple and TC310 for the Super 3. The exception to the T300 rule is the original Tiger, as this is numbered as a T409, but for the purposes of this book it is a T300, as it shares most of its parts with the T300 range.

The second generation of Triumph bikes started with the introduction of the T509 and T595 models in 1997, although T300 bikes of various models were still being manufactured until 2004. From 1997, Triumph started to use the model number in the marketing and naming of the second generation bikes, hence the new Daytona being branded T595.

The use of numbers rather than full model titles makes it easier for Triumph to refer to models.

THE NEW TRIUMPH COMPANY

The original Triumph Motorcycle Company was based at Meriden (near Coventry) and closed down in 1983 after a prolonged decline, both in the face of Japanese competition and a major lack of investment. Many thought this was the end of the marque, but an East Midlands house builder, John Bloor (of Bloor Homes fame), bought the intellectual property rights to the Triumph marque and secretly set about recruiting a small design team to design a new range of bikes. The design team was set up in an anonymous industrial unit near Coventry with the staff sworn to secrecy (so much so that some thought they could still not talk to me in 2010 even though they had retired!). The team included some people who had previously worked at the Meriden plant and therefore knew how to design and package motorcycles.

The new Triumph Company also employed recent graduates with mechanical engineering background and implemented a CAD/CAM software system to replace the paper, pen and drawing boards used at Meriden Triumph. The initial tasks were to identify what was ‘best practice’ in motorcycle design and there were three aspects to this.

First, there was a need to identify possible suppliers for brakes, front and rear suspension units, chains, wheels and instruments. By the time Triumph started down this path, there were no manufacturers left in the UK who could supply motorcycle parts. The subsequent fact-finding mission included trips to Japan to meet both parts suppliers and the Japanese bike manufacturers.

Second, a range of current Japanese bikes were purchased and analysed for performance and for engineering right down to cutting them up for metal analysis.

Finally, Triumph employed consultants to provide specialist technical advice. As an example, Ricardo helped Triumph to completely understand the thermodynamics of the internal combustion engine.

The net result was that the new Triumph designed a range of engines and bikes fit for the late twentieth century and owing very little to what Triumph had previously produced. There are some urban myths that say the Triumph engine was designed and built by Kawasaki and that Triumph copied the spine frame of the Kawasaki GPZ900, but neither was true – the engines were completely designed and built by Triumph and the GPZ900 actually copied the frames from the last Meriden Triumphs. The spine frame used on the last Meriden bikes was re-engineered and stressed for a heavier and more powerful range of bikes and engines. The whole range of bikes and engines was designed on a brand new CAD/CAM system, which came as a bit of a shock to the ex-Meriden employees, who were used to drawing boards and pencils, but this was all part of John Bloor’s concept of the new Triumph as an up-to-date and modern company.

One of the key elements of the design process for the proposed range of bikes was that as many parts (fuel tanks, engines, brakes, chassis, swing arms and running gear) as possible were to be interchangeable, providing economies of scale both for Triumph and for the parts suppliers. This is very useful for those of us trying to maintain the bikes twenty-five years after they were built as we can utilize parts from other models.

In 1988, a 4ha (10-acre) site was bought in Hinckley in Leicestershire (later referred to as T1 to differentiate from later factories in the UK (T2) and abroad (T3, T4), and construction of the new factory commenced. When built, it was one of the most modern motorcycle factories in the world, and continues to keep abreast of the latest technologies. However, at that point the whole project was still a secret until the new bikes were launched on 29 June 1990, when the motorcycle press was invited to the new factory to see both the bikes and new facilities.

The reaction of the assembled journalists was of stunned surprise as they were shown a fully functioning modern motorcycle factory when they were expecting a shed-based operation with three employees. The motorcycle press had already seen some false dawns with the launch of Hesketh and the many attempts to restart Norton, where the products were massively underdeveloped and companies permanently short of cash, lurching from one crisis to another. The new Triumph was in a completely different league. John Bloor invested many tens of millions of pounds to ensure that this was a serious and professional outfit. The pre-production bikes on display for the visit of the journalists included some colour schemes that did not find their way onto production bikes, but were part of the process of getting feedback from all sources.

The range of bikes was launched to the world at the Cologne motorcycle show in September 1990 and John Bloor flew the entire Triumph staff (at that time around fifty) to the show. Research undertaken by the staff on the Triumph stand for the show resulted in further refined colour schemes and models. For example, Triumph displayed a Daytona in an all-white paint scheme but this was not carried forward into production.

THE NEW MODELS

In December 1990, the initial range of three bikes was launched at the International Motorcycle Show at the NEC Birmingham, and in February the first production bikes (1200cc 4-cylinder Trophies) were shipped to the German market, as it was felt that if the Germans liked the quality then the rest of the world would.

Production started at around five bikes per day and gradually increased over the coming months. The initial model range consisted of:

The Trophy (for touring)

900cc triple

1200cc 4-cylinders

The Daytona (sports alternative)

750cc triple

1000cc 4-cylinder

The Trident (roadster)

750cc triple

900cc triple

An early Trophy 900 in Charcoal Grey Metallic with two-piston front calipers and six-spoke wheels. The exhaust is an aftermarket replacement.

Early Trophy 1200.

A Daytona 1000 in Assam Black with blue stripes; this model was only made in 1991 and 1992.

An early 900 Trident showing the six-spoke wheels and two-piston sliding caliper front brake.

The range remained the same in 1992, but for the 1993 model year the Daytona 750 and 1000 were deleted and were replaced by the Daytona 900 triple and the Daytona 1200 four, as Triumph reacted to customer demand and feedback. The initial range was hedging its bets between the 3-cylinder triples and the 4-cylinder engines, but it was soon clear that the triples were the most popular and were to be the main engine power unit. The 1000cc 4-cylinder engines are quite rare as not many bikes were sold; as a result, the engine was dropped and replaced by the 1200.

A 1200 Daytona.

Another new model was the Sprint 900, which was in effect a half fairing fitted to the Trident; initially the model was known as the Trident Sprint.

An early Sprint painted in Caspian Blue with grey engine cases. The exhausts have been replaced on this bike.

In 1993, another model added to the range was the Tiger, with its enduro styling.

A Tiger in Pimento Red. The early bikes had the clutch cover painted the same colour as the body but there were problems with the paint adhering to the cover, so the clutch cover reverted to black.

A Tiger; note the hand guards.

The Tiger set a new trend as it had a plastic tank; Triumph was one of the first manufacturers to use plastic for fuel tanks, followed by Ducati. This was also the first Hinckley Triumph with spoked wheels.

For 1994, a number of new models were announced, including the Speed Triple, Super 3 (with carbon-fibre mudguard, rear hugger) and the Trident Sprint.

A 1994 Speed Triple in Racing Yellow and a 1995 Speed Triple in Fireball Orange. The orange bike has the original mirrors, while the yellow one has had aftermarket bar end mirrors fitted.

A 1996 Speed Triple with Yoshimura aftermarket silencers.

The Daytona Super 3 was produced over three years and was the same all the way through, except for the change to gold brake calipers for 1996. Just 805 bikes were built. This bike has aftermarket silencers produced in America by D&D.

A Super 3 rear hugger in carbon fibre.

The Speed Triple was introduced with a five-speed gearbox, while all other models in the range had six speeds. Many components were also upgraded, so four-piston brake calipers made an appearance along with revised crankcases (eliminating the cover for the sprag clutch) and the three-spoke 17in wheels. The earlier 18in six-spoke wheels continued with some models alongside the new three-spoke wheels.

This Thunderbird still has the two-piston caliper fitted to a single disc.

The crankcases were revised in conjunction with Cosworth, who had expertise in casting aluminium crankcases (Cosworth have their own specialist foundry company) and this redesign saw the demise of the sprag clutch cover. The objective of this redesign was to reduce weight without any detriment to oil-tightness. In October 1994, the oil pickup was modified for the 3-cylinder models. This was owing to some oil starvation issues identified on the Speed Triple Challenge bikes, where pulling wheelies was common, as was the nose of the bike diving under heavy braking, causing oil surge in the sump.

At the same time, the first of the retro models, the Thunderbird, was on display ready for the 1995 model year.

This was a departure from the previous T300 in that the fuel tank was different and it was the first bike to have a ‘retro’ feel, harking back to the Triumphs made at Meriden. The engine cases for the Thunderbird (and the later Legend, Thunderbird Sport and Adventurer) were revised with more fins, and the engine covers as well and oil breather system were also revised, identified by the different clutch cover and figure-of-eight covers on both sides of the engine.

A 1996 Trophy 1200 with revised fairing, complete with pannier set. The control plates to hold the foot pegs were revised for the Trophy and the Sprint Executive.

This model year also saw the change from PVL to Gill igniters in an effort to improve starting and lessen any problems with the sprag clutch. The Gill igniter had a revised start voltage and ignition curve and also allowed the engine to spin over twice before attempting to fire the plugs. A different method of connecting the wiring harness was implemented at the same time. The PVL had a detachable connector while the Gill did not.

At the end of 1995, the revised Trophy 900 and Trophy 1200 were announced for the 1996 model year.

The styling for the redesigned Trophy was completely different from the previous version, with a new fairing, twin headlamps and revised ergonomics intended to create a more relaxed riding position, particularly when touring. The revisions included different handlebars with a greater pull-back as well as redesigned foot pegs (and foot peg brackets) and a new instrument panel. The rear light also changed.

The Daytona and Speed Triples also had the calipers changed to a gold finish.

In 1996, another new model, the Adventurer (derived from the Thunderbird), was announced.

The Thunderbird and the Adventurer received oval swing arms. Also for the 1996 model year, the Speed Triple was fitted with a six-speed gearbox (although it is thought that some late 1995 bikes also had this).

The Trophy had revised rear lights from 1996 onwards.

However, 1996 was the year that started the end of the T300 range, as the new T595 and T509 models were announced and the transition from T300 to T500 had started. The T500 range had different frames and engines (although the engine internals were very similar to T300s). Nevertheless, the T300 continued on for a few more years.

Shorter front forks (25mm/1in shorter) were fitted to all the Speed Triple and Daytonas in 1996 and the rear shock absorbers were also revised to be lighter and with greater adjustability. The longer forks were retained for the Trophies, Tridents and Sprints as the handlebars were attached to the fork legs above the top yoke. The Tiger gained a new rear rack.

A 1996 Daytona.

A 1997 Adventurer in Amber and Copper. The bike was a development of the Thunderbird and aimed at the cruiser market in America.

A number of run-out specials were also announced at the end of 1996 for the 1997 model year, including the 750 Speed Triple (approximately 300 bikes); this bike was not just a smaller Speed Triple 900 as it reverted to the earlier six-spoke wheels with narrower rims than the 900 version, although it appears that some 750 Speed Triples were built with the three-spoke wheels. The 750 had the shorter adjustable forks as fitted to the 900. However, a new model, the Sprint Sports (a sort of T300 900 Speed Triple but with a Sprint fairing), was also introduced in limited numbers for the 1997 model year (eighty bikes).

The Sprint Sports was introduced in 1996 in Diablo Black, initially as a limited edition of eighty bikes.

Both the Sprint Sports and 750 Speed Triple were intended to use up supplies of T300 engines and components, as the new T509 Speed Triple used the new engine.

For the 1997 model year, the T300 Speed Triple was deleted from the range and replaced by the T509 version. However, bikes were in stock at dealers and were still being registered until 1999! The rear light for the Sprint Sports was also revised from the Trident/Sprint one and was similar to the one used on the revised 900 and 1200 Trophy.

The revised rear lights for the Sprint Sports.

Another version of the Sprint, the Sprint Executive, had revised foot peg brackets, similar to the revised Trophy, and was sold complete with luggage.

For 1998, the Thunderbird Sport was introduced, very much in the café racer mould.

The Sprint Executive, introduced for 1997 and 1998.

The Sprint Sports was also continued after the sell-out of the 1997 version. It was now offered in black and red and not limited in numbers as its predecessor was. Another variant of the Thunderbird, the Legend, was also announced and was available in 1999.

The Daytona 900 and 1200 were also deleted from the Triumph catalogue as the T300 Daytona 900 was replaced by the new T595 Daytona. Although the standard Daytona 1200 had been deleted, Triumph released a new version called the Dayton 1200 SE. This version was limited to 250 bikes (all with a numbered plaque on the top yoke) and the bike featured Alcon six-piston calipers, gold wheels and black paintwork with gold ‘Daytona’ on the side. The power for this bike was 147bhp, so it was a bit of a flyer! This was the final version of the 4-cylinder sports bike range.

For 1999, the Thunderbird was deleted from the range, but pressure from the dealers and customers prompted Triumph to reintroduce the bike. Triumph also brought out the Sprint ST, a fuel-injected bike, leading to the deletion of the T300 Sprint and Sprint Sport. The Trophy had further revisions to its fairings and screen to improve comfort as well as a longer side stand and aluminium handlebars, although the weight saving on a bike weighing more than 260kg (570lb) was negligible. The T300 Tiger was deleted and replaced by the new fuel-injected version.

Thunderbird Sport with the original exhausts.

The first version of the Thunderbird Sport, with the twin silencers on the same side.

The Legend, introduced in 1999.

A Legend showing the revised engine cases.

A Daytona 1200 SE fitted with Alcon six-piston front brake calipers.

By 2000, the T300 line-up consisted of the Legend, Thunderbird, Thunderbird Sport and the Adventurer, all part of the ‘retro’ range, and the Trophy 900 and Trophy 1200 as tourers.

The Thunderbird Sport had some revisions, with the silencers now being either side of the bike where previously the twin silencers were on one side only.

Another nail in the coffin for the T300 bikes appeared in 2001 with the new twin-cylinder Bonneville, which was the start of a new ‘classic’ range. This then extended into a Thruxton model and a number of different Bonneville models, all building on the Meriden heritage. These new bikes were considerably lighter than the Thunderbirds, Adventurers and Legends.

For 2002, the Trophy 900 was deleted (leaving the Trophy 1200), as was the Adventurer.

For 2003, only the Thunderbird Sport (reintroduced after a two-year gap) and the Trophy 1200 were being built, and for 2004, only the Thunderbird Sport was available; at the end of the year they were deleted, ending the production of the T300 spine-framed bikes.

As mentioned earlier, all bikes manufactured by Triumph had been ordered by dealers, so long after a particular model was deleted you could still find one at a dealership. The Daytona 900 that I have converted into a CRK Café Racer was built in 1995 but not registered for the road until 1997, and I am aware of a Speed Triple built in 1996 not being registered until 1999. You could also find one-off paint schemes. The Daytona Super 3 I owned left the factory in Racing Yellow (as were all Super 3s), but sat at the dealer’s for a long time; then the first customer had it repainted in black when he took delivery, which confused a number of people. It was restored to Racing Yellow when I bought it. Any Triumph employee ordering a new bike could have it painted any colour, so a number of bikes left the factory in non-standard paint schemes.

The table opposite shows the model years when the bikes were listed, although bikes could be available for a few months before the model year started.

PART NUMBERS

This might seem simple – just find the part number to order the parts and then fit. However, problems can sometimes arise when Triumph modified or upgraded a part (such as the oil feed banjo that feeds oil to the cylinder head) but retained the original part number. In most cases this is of no consequence, as it is an upgrade, but for some parts it is: for example, I ordered some replacement engine bolts for my Speed Triple as the black finish was a bit flaky, but when they arrived they were in silver but with the same part number! The silver bolts had superseded the black ones and only silver was available. So, where there is a superseded part, check that it is exactly what you want.

IDENTIFYING THE MODEL

At the time of writing, the majority of the T300s produced are over twenty years old, and any individual bike may have had many owners and undergone many changes, as the modular design would enable different bodywork, engines and so on to be fitted. Fairings may have been removed and sometimes bikes try to masquerade as a different model, the Speed Triple being particularly subject to this type of counterfeiting. In short, it is possible that the bike you may be buying may not be the bike you think it is. I have seen a Daytona with Speed Triple bodywork and the fairing removed, but the VIN number would show its origins as a Daytona. The safest option is to check the VIN number and see if it marries up with the model description.

This Thunderbird Sport is the revised model, with the single exhaust on each side.

The easiest way to find the VIN number on your bike is to look at the cross-member under the seat, where there is a metal plate.

The VIN number is also stamped on the front of the headstock but, unless you have removed some of the headlights/ wiring, it is very difficult to see and read. This is useful, however, if you buy a bare frame with a V5.

The VIN is broken down into the components listed below, identifying the model, engine, gear ratio and year manufactured.

When ordering parts it may be necessary to give the full VIN number to ensure you get the correct parts.

WHAT DOES YOUR VIN NUMBER MEAN?

Note, only the models covered in the book are listed in the table below, and the VIN numbers are for UK bikes only. The VIN numbers for Triumph bikes sold to other markets across the world are different – for example the Speed Triple is listed as 390 for America and Canada and 301 for the UK market. This can cause complications, as Triumph sometimes brought unsold bikes from, say, America to sell in the UK or offered bikes that were originally destined for a foreign market but remained in the UK.

The VIN number is on a plate under the seat.

The VIN number is also stamped vertically on the headstock, where it is very hard to see!

The VIN number is broken down as follows, using an example of a 1994 Speed Triple with a VIN number SMTC301DMR123456:

SM

Manufacturer (Triumph)

TC301

Frame/model (Speed Triple)

D

Engine type (885cc)

M

Final drive ratio (17/43)

R

Year code (1994)

123456

Serial number

The codes relevant to all the T300 models are given below, including different engine horsepower ratings for the same model.

Frame/model

301

Speed Triple

310

Super 3

330

Daytona 750

331

Daytona 750

332

Daytona 750

333

Trident 750

335

Trident 750, 50hp

336

Trophy 900

338

Trident 900

339

Thunderbird

340

Trophy 1200

341

Trophy 1200,125hp

342

Trophy 1200, 100hp

343

Daytona 1000

344

Daytona 1000, 100hp

345

Trophy 1200, 149hp

354

Daytona 1200

357

Daytona 900

362

Sprint

364

Sprint Executive

365

Sprint Sports

396

Legend TT

398

Thunderbird Sport

399

Adventurer

409

Tiger

Engine type

C

1200cc

D

885cc, 98hp

G

885cc, 115hp

J

885cc, 70hp

K

885cc, 108hp

L

955cc, 108hp

M

955cc, 110hp

N

885cc, 87hp

R

885cc, 83hp

S

599cc, 110hp

T

790cc, 62hp

V

955cc, 149hp

X

955cc, 149hp

Final drive ratio

A

17/52

B

17/50

C

17/48

D

17/46

E

17/44

F

18/45

G

18/43

H

19/43

J

19/42

K

18/48

M

17/43

R

18/44

Year code

L

1990

M

1991

N

1992

P

1993

R

1994

S

1995

T

1996

V

1997

W

1998

Y

2000

1

2001

2

2002

Serial number

100001xxx

2

modular design

One of the key features of the T300 range is the modularity and the sharing of many components across the range. This was driven by the need for Triumph to keep costs down and to have a wide range of models that underneath shared many components. This use of shared parts is of benefit to owners in that many parts are interchangeable, making sourcing them easier. However, there are differences that could trip up the unwary.

FRAMES

While the curved spine frames, made from high-tensile (600MPa micro alloyed) steel and sub-frames are all similar – being an updated version of the spine frames used on the Meriden Triumphs – and while they may look the same, they are not necessarily identical.

A bare frame from a Speed Triple showing the spine frame common to all the T300s (with small variations).

The sub-frame on a Speed Triple.

The Daytona/Trident/Trophy/Sprint and Speed Triple frames are the same, but the top and bottom yokes have different degrees of offset.

The frames and sub-frames for the Thunderbird/Thunderbird Sport and Legend have different fitting points for the water system header tank, which is located at the top of the spine frame; the Daytona/Trident/Speed Triple/ Sprint have the header tank located behind the tank and sitting down inside the sub-frame.

Thunderbird water pump.

Header tank on an Adventurer.

The seat sub-frames are not all identical and vary from model to model, particularly on the Thunderbird/ Adventurer/Legend and Tiger ranges.

The rake angle for the forks can also vary – for example, the Adventurer of 1999 had a 27-degree rake angle.

It is an urban myth that Triumph copied the spine frame of the Kawasaki GPZ900. Rather, Kawasaki copied the spine frame from the Meriden Triumphs, and the revised spine frame for the Hinckley bikes had been designed a few years before John Bloor set up Hinckley.

FRONT FORKS

Triumph used two Japanese suppliers for the front forks – Kayaba (early and some later models) and Showa (late) – but all forks share the same 43mm diameter chrome tubes irrespective of which model or supplier, some being adjustable, some not. For 1996, the front forks were shortened on the Speed Triple and Daytona, and models that previously had the forks showing through the top yokes now had the fork tops flush with the top yoke, or with a lower ‘pull-through’. The Tridents/Trophy/Sprint and Sprint Sport retained the longer forks for attaching the handlebars above the top yoke.

Kayaba adjustable forks were fitted to Daytona 750/900/1000, Speed Triple 750 and 900, Sprint Sport and Super 3 models.

All non-adjustable models (except the Sprint 900, which was only fitted with Kayaba) had either Showa or Kayaba. All adjustable forks were Kayaba.

Tiger front forks had a different bottom (slider), using longer tubes with the same damper system as other non-adjustable forks as follows; these were Kayaba up to VIN 43523 and Showa from VIN 43523 to VIN 71698 (when the new Tiger 900i replaced the T400).

The Kayaba had 55mm outer seal diameter (originally a smooth dust seal was visible) and these had a larger damper bolt at base. The Showa had a 54mm outer seal diameter (the dust seal originally had an external visible garter spring) and these had a smaller damper bolt at base.

The forks allowed an upgrade from 296mm solid discs to 310mm floating discs by many owners. If the larger discs are fitted then you must fit the later four-piston calipers. The brake caliper fixing hole centres are the same (this does not apply to Tiger 900 and Thunderbird range). It’s a good idea also to upgrade the front brake master cylinder from 14mm to 5/8in (15.87mm) to reduce lever travel.

Fitting of 955 Sprint ST bottom sliders allows 320mm discs to be used. All Showa parts have to be used, as these do not interchange with Kayaba. Even the top fork nuts have a different pitch thread – being aluminium alloy and fine threaded, this can lead to a thread crossing mistake, and this can be expensive!

Non-adjustable forks were softly sprung and dive with brake application. Springs can be upgraded (normally with multi-rate springs, but linear springs are always better) and some customers use heavier damping oil, but one change at a time is the best way to progress. The later nonadjustable forks (certainly Kayaba and probably all Showa) reduced the diameter of the damper port hole to restrict damping oil flow.

Fork bushes are not interchangeable between Kayaba and Showa. There is a view that Showa are better engineered apart from having a narrower (15mm) bottom bush. Kayaba use 20mm bottom bushes.

Fork damper holding tool on nonadjustable forks is a 30mm hexagonal nut welded to a long tube. Adjustable forks need a 20mm-long piece of square tubing.

FOOT PEGS AND FOOT PEG BRACKETS

The foot pegs for the rider can be in two positions: a lower one for the touring bikes and a higher one for the Daytona and Speed Triple. This is because the control plate to which the pegs are attached can be mounted in two positions. If you want to fit lower rider foot pegs to the Daytona and Speed Triple, the gear linkage and rear brake pushrod will also need to be changed. There are also two types of foot peg, as shown here, which gives four different positions in total – two by the pegs themselves and two on the control plate.

Control plate for a Daytona, with the foot peg in the upper position.

Control plate on a Sprint, with the foot peg in the lower position.

Different types of foot peg brackets.

The Trophy foot pegs are wider than those on the Daytona, Trident and Speed Triple.

The rear foot peg brackets are also of two types, depending on what style of exhausts are fitted to the model. The longer ones are for the Trident/ Sprint as the exhausts are lower, and the shorter foot peg brackets are fitted to the Daytona/Speed Triple and Sprint Sports, as the exhausts are at a steeper angle.

The foot peg brackets for the later Trophy and Sprint Executive are different to the rest of the range as the control plate is a one-piece casting for both rider and passenger pillion foot pegs.

The rear foot peg brackets and exhaust hangers for the Daytona 750 and Daytona 1000 are different from any of the subsequent models, as they incorporate a welded tube arrangement for the exhaust hanger; the alloy foot peg bracket is only for the foot peg.

The different rear foot peg hangers depending on which exhaust was fitted. The shorter one appeared on the Sprint, Trophy and Trident, the longer one on the Speed Triple, Daytona and Sprint Sports.

Pillion foot peg brackets for the 1991 and 1992 Daytona 750 and 1000. The tubular frame is the exhaust hanger. Triumph later combined the exhaust hanger and foot peg hanger in one casting.

Revised control plate on the later Trophy and Sprint Executive.

Control plate on a Triumph Sprint Executive and the revised Daytona.

On later models, Triumph combined the functions so the foot peg hanger also serves as the exhaust hanger.

GEARBOXES

The bikes were originally fitted with six-speed gearboxes, except for the Speed Triple and Thunderbird family, which had five-speed ones. In late 1995, the Speed Triple was provided with six-speed gearboxes, as was the Thunderbird family some time later. The five-speed gearboxes can be upgraded with the additional gear if required, although I have to say I did not notice any appreciable difference between the five- and six-speed bikes under normal riding conditions.

SWING ARMS

The swing arms are made of extruded high-tensile aluminium, welded in a jig and then anodized, either in grey, silver or black depending on which model they were fitted to.

A swing arm for a Daytona or Speed Triple in black. This has been refurbished and powder coated; the factory finish was anodizing. Other models had a similar swing arm but in grey or silver.

There are a number of variants in the swing arms. The swing arm for the Daytona and Speed Triple has the rear caliper slung under the swing arm, while the Trident/Sprint has the rear caliper above it, so the caliper mounting points and location for the tie bar between the caliper and frame are different. The first generation Trophy and Trident with six-spoke 18in rear wheel and silver swing arm had the rear brake caliper above the swing arm.

Rear brake caliper over the swing arm on a Trident.

Underslung rear brake caliper from a 1996 Speed Triple in gold.

A Thunderbird swing arm that has been powder coated.

Thunderbird swing arm from underneath.

The swing arms for the Thunderbird/Thunderbird Sport and Legend are different in appearance.

TOP AND BOTTOM YOKES AND HANDLEBARS

The variety of top yokes is considerable, although the majority of the differences are cosmetic, as some are polished and some powder coated black or silver. There are also different offsets depending on the model, so Daytona has a 40mm offset while the Speed Triple has 35mm offset. Some models had the handlebars above the top yoke – the Trophies, Sprints, Sprint Sports and Tridents – while the Daytona and Speed Triples had handlebars below the top yoke, and the Adventurer, Thunderbird and Legend had the top yokes drilled to take clamps to hold the one-piece handlebars.

A selection of top yokes: 1004 later Trident, 1005 Tiger, 1006 Thunderbird.

Top yokes: early Trophy at the bottom and Daytona at the top.

There is a large range of handlebars fitted to the various models and some can be interchanged between models, as all the forks are the same diameter of 43mm. Some handlebars fit below the top yoke – the Daytona and Speed Triple – and some fit above and are bolted through the top yoke, as on the Sprint, Sprint Sport, Trident and Trophy.

Sprint Sports handlebars.

Later Trophy handlebars.

Other models have the bars above the top yoke held by clamps bolted through the top yoke, as on the Thunderbird and Legend.

One of the most popular handlebars to fit is those from the Sprint Sports (and early Trophies) as they raise the position for a more relaxed ride (on the Daytona and Speed Triple) but give the café racer look. These bars can be fitted to a Daytona as they maintain clearance for the fairing and use the standard Daytona cables, hoses and wiring. The top yoke will not need to be drilled out to take the retaining bolts, as on the Daytona the threaded holes are already there. For a Speed Triple, however, the top yoke will need to be drilled out. If you fit Sprint Sports handlebars to a Speed Triple, the fork tubes will need to be changed to ones from a Trident, as they are longer and fill in the gap where the original handlebars fitted.

A set of Trident handlebars.

Thunderbird Sport handlebars.

Daytona bars have a small ring on the side, the Speed Triple ones do not.

A selection of handlebars from various T300 models.

Daytona handlebars. The Speed Triple ones are very similar, minus the little ring welded on the side. These fit under the top yoke.

The last Trophies (from 1999) had aluminium handlebars.

The different handlebars also resulted in different bar end weights, so the Speed Triple, Daytona and so on had the bar end weights held to the handlebar by a small Allen-headed countersunk bolt that screws through the bar end weight and into an insert within the handlebar. The early Trophies and Sprint Sports had bar end weights that were threaded and they screwed in the handlebar end. The size and pitch of the thread does not allow these to be interchangeable.

Some of the different bar end weights, depending on the model.

Bar end weights, with two types of fixing; the handlebars need to match the bar end weights.

Sprint Sports handlebars and bar end weights.

The Trophy for 1996 and 1997 had new bar end weights containing ‘dynamic vibration absorbers’. These were also seen on the 2002 and 2003 Trophy 1200. The bar end weights for the later models are also physically smaller than the bar ends for the 900.

The T300 range offers an infinite variety of riding position from the ‘drop’ bars on the Daytona and Speed Triple to the ‘comfy’ bars fitted to the Trophies, and most things between.

REAR SHOCK ABSORBERS

There are two main types: adjustable ones, fitted to the Daytona (both 900 and 1200), Speed Triple, Trophy (both 900 and 1200) and Sprint Sports; and non-adjustable, fitted to the early Sprints and Tridents. Replacement new rear shock absorbers are no longer available from Triumph and they cannot be rebuilt or refurbished – beware any advert that says that they can. If your rear shock is high mileage then replace with an aftermarket one such as Hagon, YSS or one from a specialist company such as Maxton or Nitron, or one from a race company.

Rear shock absorbers: early Trident (1991 and 1992) on the left, and twin-headlamp Trophy on the right.

Standard rear shock on a Daytona.

This was the standard tank except for the Adventurer, Legend and Thunderbird range, which had a different-shaped unit.

Adventurer tank in Amber and Copper.

The rear shock absorbers came in two lengths, as the earlier bikes were fitted with 18in rear wheels and later bikes were fitted with 17in; so, for example, the Speed Triple 750’s were shorter than the 900’s as it had an 18in rear wheel. If you change the early 18in wheels for the later 17in type, then fit a longer rear shock to compensate for the difference in wheel diameter in order to retain the excellent handling characteristics.

PETROL TANKS

There are three different fuel tanks in the T300 range. The most common is that fitted to the Daytona, Trophy, Trident, Sprint, Sprint Sports and Speed Triple, which is made of steel.

The underside of a Daytona petrol tank, showing the fuel tap position at the bottom and the fuel sender unit position at the top.

The tank fitted to the Thunderbird, Thunderbird Sport and Legend is different in shape to the Daytona/Trident one and has a smaller fuel capacity, but is also made of steel.

Lastly, there is the fuel tank fitted to the Tiger, which is made of plastic and will only fit a Tiger. Triumph had to have the vehicle regulations changed to allow the fitting of a plastic tank to a motorcycle and was the first manufacturer to produce a bike so fitted. Plastic fuel tanks are now common across many manufacturers.

The Tiger fuel tank.

Water header tank used on the Thunderbird, Thunderbird Sport, Legend and Adventurer.

Thunderbird Sport water header tank.