Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow Ltd

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Serie: Floodworld

- Sprache: Englisch

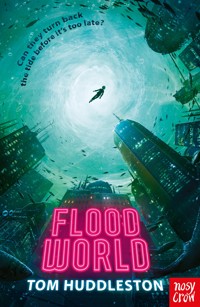

FloodWorld is a gripping, action-packed story for 10+ readers. Kara and Joe spend their days navigating the perilous waterways of a sunken city, scratching out a living in the ruins. But when they come into possession of a mysterious map, they find themselves in a world of trouble. Suddenly everyone's after them: gangsters, cops and ruthless Mariner pirates in their hi-tech submarines. The two children must find a way to fight back before Floodworld's walls come tumbling down... With cover illustration by Manuel Sumberac. "An action-packed, edge of the seat thriller" BookTrust

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 306

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Pat & Kat

“I would not creep along the coast but steer Out in mid-sea, by guidance of the stars.”

George Eliot

1

The City and the Sea

Joe skidded to a stop, breaking from the shadow of the buildings to stand in wonder at the water’s edge. Ahead of him the filthy brown sea met the cloudless blue sky. In the distance a line of tower blocks jutted from the water, waves lapping at the middlemost storeys.

“Hey!” Kara called. “Don’t run ahead.” Her bare feet pounded on the wooden walkway as she came up behind him, her face flushed and her dirty yellow hair coming loose from its knot.

“I wanted to see the boats,” Joe said. “I like the boats.”

The Cut was busy today, the shipping lanes crowded with rusted tankers and boxy haulers, some creeping into port while others rattled off towards open water and destinations unknown. Local fishing sloops tacked between them, patchwork sails stiffening in the breeze. All of them were going somewhere. Somewhere that wasn’t here.

“It’s dangerous out this way, you know that.” Kara placed a protective arm round his shoulders. “We’re a long way from home.”

She was right, as usual. The Spur was the most notorious neighbourhood in the Shanties, an outflung tangle of wooden catwalks, shadowy towers and winding waterways miles from the heart of things. Only the very poor or very secretive made their homes out here.

“This ain’t a race, you know,” a voice called, and turning back Joe saw Mr Colpeper struggling behind them, his bald head scarlet and glistening. Far beyond him the Wall rose from the concrete and driftwood sprawl of the Shanties, its sloping side sparkling with a layer of crystal salt. At its base was the harbour, a busy ant’s nest prickling with cranes and masts and security towers.

Colpeper wheezed to a halt, his hands on his knees. “You kids’ll be the death of me, I swear.”

“You’re getting fat,” Kara said. “What? It’s true.”

Colpeper’s mouth tightened, then he barked a bitter laugh. “You don’t mince words, do you, sweetheart? One of these days that mouth’ll get you into trouble.”

He hitched up his jeans, staring out along the Spur. A short distance ahead the walkway tapered to its end, the blocks petering out into a rickety huddle of rafts and shacks. Beyond that there was nothing but open ocean.

“Past the pub then look for the spire, my dealer said.” Colpeper rubbed his hands. “He’s already got a buyer lined up in the City. This could be it for us, kids. Top dollar, right in our pockets.”

“Where have I heard that before?” Kara muttered sceptically. Colpeper was always sure this job was the big one, the chance of a lifetime. But somehow it never quite panned out.

Waves lapped at the concrete pilings as they moved along the walkway. An old man perched on the edge, clasping a homemade fishing rod. What’s he expecting to catch? Joe wondered. Rusty cans and bleached bones. Perhaps he was one of the ancient ones, who remembered London before the last barrier broke. Who’d lost everything to the waves.

Joe had tried to imagine a life on dry land, but he was never quite able to grasp it. Solid earth under your feet and all that green stuff – what did they call it, grass? The Shanties might be smelly and hectic and dangerous, but this was the only world he’d ever known.

Well, that wasn’t strictly true. He’d been to another world, one that few ever got to see. And it was almost time to go back.

“Keep up,” Kara called over her shoulder. “Honestly, first you run off, now you’re stood there daydreaming.”

She reached out and he took her hand, enjoying as he always did the sight of his little brown paw clasped in her big rosy-pink one. She tugged him forward, resentfully at first, then with a smile. “You are such a pain in the bum,” she laughed. “I don’t know why I let you hang around with me.”

“Because you lurve me,” Joe told her. “You lurve me so much, it’s disgusting.”

Kara lowered her head and kept dragging. “Horrid. Little. Brat,” she grunted with each tug.

“Quiet, you two,” Colpeper said abruptly. “This isn’t the place for games.”

A rusty shack loomed ahead, casting the walkway into shadow. The raft beneath it rocked in the wake of a passing ship and the whole structure creaked and groaned. Through the open door Joe could see figures moving through a fog of sweet smoke. He heard the clink of glasses and smelled the sour tang of a strong, locally brewed drink folks called Selkie.

“This is the Last Gasp,” Colpeper whispered. “Only the really bad crooks drink in here.”

“Favourite of yours, then?” Kara smirked.

Colpeper nodded. “It was, back in the day. Before I went legit. You’re lucky you didn’t know me then, I wasn’t half so good-natured.”

His voice was almost wistful, and Joe wondered how much Mr Colpeper had really changed. He was decent enough most of the time, but when he got in one of his tempers no Beef would dare stand up to him.

They passed the pub, approaching the tip of the Spur. Squinting ahead, Joe realised this might be the furthest from home he’d ever been. Across the water he could make out a smudge on the horizon – the hazy mainland shores of Wycombe and the Chilterns, so distant and unattainable he might as well have been gazing at the moon.

“That must be the spire,” the big man said, gesturing south into the waters of the Cut. The peak of a building broke the surface, topped with the outline of a black bird. Joe peeled off his shirt and Colpeper unzipped his pack, taking out a rubber mask and a steel canister. “Just take a look for now. If the goods are intact, we’ll see about proper salvage.”

Joe nodded, clipping the tank to his cargo shorts and biting down on the mouthpiece. The oxygen tasted of old rust.

“And don’t take any stupid risks,” Kara warned him. “It’s not worth it.”

Joe frowned. “I hab dud dis befaw, oo no,” he told her, the mouthpiece garbling his words. It was good that she worried, but sometimes he wished she’d put a bit more trust in him.

He dropped to the boards, flippers dangling over the edge. Scum glistened on the water, a seagull carcass grinning from a nest of seaweed. The Stain, they called it, a festering vortex of garbage and human waste that spread from the Shanties for miles in every direction. But he had no choice; they’d come all this way. So he braced himself and took the plunge.

Joe trod water, taking a good look left and right. He wasn’t close enough to the sea lanes to worry about the big ships, but it’d be just his luck if some idiot on a jetski came clipping round the corner. Then he kicked out, beating a path through the muck, keeping his arms and legs tucked in to limit the risk of touching anything unpleasant. He kept his scalp shaved for the same reason; there was nothing worse than washing someone else’s poo out of your hair.

He reached the spire, the sun baking on his back. He gave a thumbs up, receiving an answering nod from Colpeper. Then he kicked off, angling down into the dark. The Stain cleared, a shaft of sunlight broke through and the world below was revealed.

The houses here were low, a maze of narrow terraces and algae-stained roofs. Joe saw shattered windows, rotting curtains waving in the current. But there were no cars – they must’ve been dragged up for scrap years ago, along with anything else the early Beefs had seen fit to scavenge. This whole area had been picked clean.

He thought of the old fisherman. Had he grown up in a street like this, before the water came? Decades had passed since then, but time had no meaning down here.

Joe turned, treading water and looking up at the building looming over him. A church, Colpeper had called it. He knew what the word meant; the Shanties were full of shacks where the faithful gathered to sing and pray. Kara had always cautioned him to steer clear – if there is a god, she said, he’s probably not someone you want to make friends with. I mean, look at the world.

But this church was different and rather grand. From the corners of the steeple sprouted four stone carvings, horned figures with spread wings. They looked oddly at home down here, watching over their sunken kingdom.

Joe scanned the nearby buildings for the word Colpeper had made him memorise. A sign said POST OFFICE, another SUPERMARKET – a large flat structure with a line of rusty carts anchored outside. Then he saw it. Letters were missing so that the sign now read “R XY C EMA”, but this had to be the place. It was a squat brick building, the entrance just a gaping rust-edged hole. Joe swam closer, taking hold of the steel frame. He peered inside.

The carpets, once red, were almost black with silt. Joe tugged the torch from his pocket, winding the crank five times, then flicking the switch. Shapes emerged from the gloom: rotted chairs and a smooth fibreglass counter. The walls were lined with pictures sealed in grimy frames. Joe wiped one clean and saw a woman wearing next to nothing holding a gun in her hand. He wondered what kind of place it had been, this cinema.

Silver winked as a school of sprats darted out of the light. Doors branched left and right, blocked with fallen debris. But in the far corner a flight of steps led up to another larger door. A sign read SCREEN ONE just like Colpeper said.

The hinges were stiff but a few cautious tugs pulled the door wide enough for Joe to squeeze through. The room inside was dark and cavernous. He felt his heartbeat quicken. It wouldn’t take much, a rotted roof beam or a rusted girder, and he’d be trapped, crushed in the rubble or buried alive until his air ran out. It wasn’t uncommon these days; with each passing year they had to swim deeper and search harder to find anything worth bringing up. The life of a Beef was getting riskier all the time.

The room was full of chairs all facing the opposite way. The far wall was perfectly flat and perfectly white, and Joe wondered why people would come in here to sit and stare at nothing. Perhaps this was another sort of church – maybe they’d flash pictures of their god on that wall and sing hymns in the dark.

Something brushed against Joe’s foot and he started. A sea snake wound into the darkness, undulating bands of yellow and black. He took a deep pull of oxygen. This place was starting to give him the creeps.

A glint of reflected light told him he’d found what he was looking for. A glass case stood against the wall, a laminated sign taped to it. The words were faded but readable: COLLECT 10 TOKENS TO CLAIM YOUR EXCLUSIVE ACTION FIGURE!

He peered closer and his heart sank. A jagged crack ran across the face of the cabinet and the inside was full of filthy water. Colpeper had been very clear – any damage and the sale would be off. Joe spat out his mouthpiece, clasping the torch between his teeth. He touched the front of the case and the glass fell away, the hinges rusted to nothing. The objects inside were soaked but he reached in anyway, fingers wrapping round something small and hard.

It looked like a sort of skinny bear standing on two feet. His fur had once been brown but the paint had soaked away to reveal textured grey plastic underneath. His lips were drawn back in a snarl, but his eyes were still blue and there was something friendly about him. Joe scratched the bear under the chin and pondered.

So this was what he had been sent to find. Plastic toys, the kind they kept in a crate at school for the younger kids to play with. And yet someone inside the City – a collector, Colpeper had called him – was willing to pay serious money for them. Maybe this collector didn’t know that someone like Joe would end up risking his life to get them. Maybe he didn’t know that the money he’d offered could keep a Shanty family alive for a year. Or maybe he just didn’t care.

Joe slipped the plastic figure into his pocket, reaching for his mouthpiece. But as he did so something scraped against his arm and he jerked round in surprise. Empty eye sockets stared back, white teeth grinning from a face picked clean.

The air exploded from Joe’s lungs, the torch slipping from between his teeth. It tumbled down into the silt and the room was plunged into darkness.

Joe scrabbled for his mouthpiece, hands shaking. He felt the skeleton drift alongside, bony fingers scraping at his scalp. He’d seen bodies before, human and animal, that was just part of being a Beef. But he’d never been touched by one before.

He found the mouthpiece and shoved it in, taking an urgent breath. The torch glimmered below him and he scrabbled for it, taking hold just as the bulb died. Lucky, he thought. A few more seconds and he might never have found it.

He wound the crank, the beam flashing across white bone. He shut his eyes and gave a shove. Limbs spun loose, ribs and vertebrae tumbling into the darkness.

He wiped his hands on his shorts, knowing it was a ridiculous thing to do. He almost laughed, then he gathered himself. The only thing left was to head back up and break the news to his boss. Hopefully Colpeper was in a forgiving mood.

2

The Chase

Kara stood on the walkway staring down into the water. Doubt tugged at her heart; it was the same each time Joe went under. She knew she was being soft, that he knew what he was doing. But they’d known two kids this year, good hard-working Beefs, who simply hadn’t surfaced. And she didn’t know what she’d do if she lost Joe.

Colpeper sat, letting his hairy legs dangle over the side. Sweat pooled in the folds of his neck. “You worry about him,” he said. “He’s lucky.”

Kara frowned. “Lucky how?”

“Lucky to have a big sister looking out for him.”

“I’m not his sister,” Kara said. “And if I was any good at looking after him he wouldn’t be risking his neck for a few measly quid.”

Colpeper grunted. “Don’t be so hard on yourself.

In the Shanties you either work or you starve; it’s not your fault Joe’s skills are more valuable right now than yours.”

Kara frowned. “What skills? I don’t have any skills.”

“Come on,” Colpeper grinned. “You can hot-wire a speedboat faster than anyone I ever met.”

“I don’t do that any more,” Kara said. “Not after last time. That docker would’ve killed me if he’d caught me.”

Colpeper struggled to his feet. “I’ve actually been meaning to have a word with you. I’ve a prospect on the horizon. I know, you’ve heard it before. But this one could be the answer to all our problems.” He was trying to seem casual, but Kara could hear the edge in his voice. She’d heard rumours that Colpeper owed big money to bad people, that he’d borrowed from the Shore Boys and couldn’t cover his payments.

“A certain acquaintance has tipped me off about a few possibilities,” he went on. “Shipping, import-export, that sort of thing.”

“You mean smuggling,” Kara said. “Smuggling what?”

Colpeper shifted uncomfortably. “Well, you know, protective devices. Defensive supplies.”

Kara’s eyebrows shot up. “You’re going to run guns? And you want us to help you?”

“Not the boy,” Colpeper said quickly. “Not till he’s older. But look, I know you don’t like hearing it but you’re a smart girl, Kara. Nothing gets past you. And you’re tougher than you look; people always underestimate you. You’re perfect for this gig. The Beef work’s drying up, and you know what the alternatives are for kids your age in a place like this.”

Kara sighed. He had a point. “So where would we acquire these … defensive supplies?”

Colpeper flushed. “Judging from my friend’s sympathies, I guess they’d come from the Mariners.”

Kara’s mouth dropped open. “But the Mariners are terrorists! They’ve killed our people, boarded our ships…”

“What d’you mean, our?” Colpeper asked. “Maybe they raid the odd trading vessel but that’s no skin off your nose, is it? Have they ever hurt anyone in the Shanties?”

“What about that warehouse explosion in the Hackney Sink?” Kara asked. “Fifteen people died. The newsfeeds said it could’ve been ordered by John Cortez himself.”

Colpeper laughed. “I happen to know what was going on in that warehouse, and it involved a lot of unstable chemicals. The newsfeeds blame the Mariners cos it makes for a good story, and the government encourage it because it distracts poor Shanty rats like us from our real problems. But the Mariners make the best weapons, the kind you hardly ever see on the market. I can’t pass this up.”

“But they’re freaks,” Kara complained. “They don’t even have proper homes; they just float around in those weird Arks of theirs. And they eat seaweed!”

“I eat seaweed. It’s full of nutrients.”

Kara humphed. “Not for every meal.” She didn’t like the thought of smuggling guns, not from a bunch of seaweed-eating terrorists. But what choice did she have? Someone else would take her place if she turned Colpeper down, and someone else would get the money.

She unhooked a water bottle from her waistband, emptying the dregs into her mouth. The taste of san-sal formula made her gag.

“Where is that boy?” Colpeper asked, looking at his comwatch. “Shouldn’t take forever to…”

A sound tore the air, a shuddering blast echoing from the sunken towers. Kara spun, shielding her eyes. In the distance, below the Wall, a column of black smoke was rising.

Gunfire rattled in the stillness and out in the Cut something moved, weaving between the big ships. Kara saw a fast-moving blur, darting under anchor chains and bowlines, heading for the open sea. The silver jetski carried a single passenger, upright in the saddle. He wore dockers’ overalls, brown over white, and as he curved round the rust-pocked prow of a tanker he turned back, taking aim. Three distant pops sounded over the water, then he revved the throttle and the ski picked up speed, thundering out into the harbour.

Now Kara could see what he’d been shooting at. A MetCo gunboat came slicing through the shallows, riding low and fast, gushing chemical smoke. Uniformed cops huddled behind the plastiglass rear-gun seat. One of them strapped himself into the rear gunseat, kicking at the controls. The twin barrels spun and rose, training on the fleeing jetski, compensating for the bucking of the speedboat as it rocketed through the water.

There was a roar and the cannons spat blue fire. The jetski twisted just in time, banking violently, sending up a wall of spray. The firebolt hit the water, plumes of steam rising.

The rider scanned the Spur desperately, looking for any route back into the Shanties. He angled towards the Last Gasp, where a wooden jetty branched out into the Cut. Beside it the pilings parted, forming a low bridge. If he ducked, he might make it.

The ski drew closer, and closer still. Kara could hear the whine of the propeller, could see fear in the rider’s eyes.

Then she saw another shape, low in the water, right in the jetski’s path. A dark brown head broke the surface and she cried out in horror.

Joe spat out his mouthpiece, gulping real air. He swallowed, and as his ears popped he heard the roar of an approaching engine. He twisted, trying to take his bearings.

His breath stopped. The jetski was less than fifty feet away and coming fast. There was no time to swim clear, and if he tried to duck the propeller would slice his head open. He felt his bladder go, warmth on his legs.

Then the rider saw him, and for the briefest moment their eyes locked. He was a young man, thin and bearded, his eyes widening in panic. He glanced up at the Spur and the choice was plain – hold his course and end Joe’s life, or turn aside and risk his own. He gripped the bars as the ski closed in, twenty feet, now ten. Joe bit his tongue and waited to die.

At the last second the young man tugged on the steering bar and the ski slalomed sideways. Joe felt the wind of the propeller as it missed him by inches, the ski gliding on the glassy surface of the water. It spun once, twice, then it hammered into the jetty behind the Last Gasp and exploded. The rider was thrown free, slamming into the boards, his uniform ablaze.

Joe swam as hard as he could. The jetty had been split almost in two, staves splayed and planks uprooted. The ski lay upended, the propeller chewing angrily at the air. Joe pulled himself from the water, kicking off his flippers. He tasted smoke and chem fumes.

The rider had rolled on his back, dousing the flames. Now he lay still, his eyes wide and sightless, his face scorched and spattered with blood. Joe ran to him, dropping to his knees.

“I’ll get help.”

But the rider coughed weakly, reaching to take Joe’s hand. He was younger than Joe had expected, his scruffy beard barely grown in. His uniform was burned black, the skin beneath blistered. Their eyes met and Joe could see fear in them, and pain, and courage. He wanted to tell him it would be OK, but he didn’t think it was true.

“I’m s-sorry…” the dying man wheezed, blood coursing from both sides of his mouth. “I’m so s-sorry…”

Joe squeezed his hand. “Don’t be sorry. You saved me.”

Then he heard a shout, and looked up.

“Get away from him!” Kara flung herself on to the shattered jetty. “Joe, run to me.”

“No,” Joe protested. “He’s hurt.”

But the rider had let go, rolling over on blistered elbows. He began to drag himself forward, summoning the last of his strength to claw his way across the jetty. Colpeper hurried towards them, panting.

Kara ran to Joe’s side, clasping him in her arms. “Are you OK?” she demanded. “Did he hurt you?”

Joe shook his head. “He saved my life. We have to call a medic.”

“No point,” Colpeper said. “He’s done for.”

The man struggled to the edge of the platform, leaving a trail of blood. He glanced back and Kara saw a look pass between him and Joe, sudden and quiet. Then the stranger gave a last push and toppled face first into the water, sinking like a stone. There was a trail of bubbles and for a moment the grey water blossomed red. Then he was gone.

Joe looked up, tears cutting through the filth on his face. “Why did he do that? We could’ve helped him.”

“He was a Mariner,” Colpeper said softly. “He’s gone back to the ocean.”

Kara looked up. “But I thought you said the Mariners never attacked the Shanties?”

Colpeper frowned. “Seems I spoke too soon.”

Kara heard engines idling as the MetCo craft drew closer. Through the smoke she saw an officer upright in the driver’s seat, gesturing at them. He had dark eyes and a black moustache.

“You three,” he said through a loudhailer. “Don’t move.”

3

London Zoo

“Try to see it from my side.”

The policeman smoothed his moustache, silhouetted in the sunlight streaming through his office window. “A Mariner terrorist is apprehended near the harbour. There’s an explosion. He flees, we give chase, but the only person to make actual contact with him is this boy. Is it just a coincidence that he happened to be in precisely the right place at precisely the right time?”

“Do we look like terrorists to you?” Kara shot back, her arm round Joe’s shoulders.

The cop shrugged. “If this job’s taught me anything, it’s that they come in all shapes and sizes.”

“And what is your job exactly? Officer in charge of scaring kids?”

The policeman glowered, gesturing to a silver badge on his shirt. “Akharee Singh, second lieutenant, London Metropolitan Police Corporation. Currently assigned to the Mariner Task Force, which means I hunt terrorists for a living. So don’t get smart with me.”

Kara bit her tongue. He was right, shooting her mouth off could only get them into more trouble. They were deep in enemy territory here, inside the Wall itself, in the concrete maze of offices, barracks and prison cells where MetCo had their headquarters. Precinct Place was its official title, but everyone called it London Zoo.

Singh’s office was unimpressive, a cramped square box with a desk, three chairs and a framed portrait of a man Kara half recognised. But the view from the window was spectacular – over the lieutenant’s shoulder she could see right across the Pavilion to the harbour and the towers beyond, their silhouettes stark against the sinking sun.

The Shanties were one big accident, Kara knew – the Wall had been built to keep the rich folks in the City safe when the waters rose, but they hadn’t stopped to think who’d cook their food and clean their houses. And so, in the upper floors of submerged blocks and the ramshackle walkways that linked them, the Shanties had sprung up almost overnight. To some it might seem strange, she thought, this floating slum clinging to the outside of the Wall. But to her it was just home.

“Let’s try this again,” Singh said, making an effort to smile. “Be straight with me, and I’ll do the same. What were the two of you doing so far out on the Spur?”

Kara flushed. “We were…”

“Sightseeing,” Joe broke in. “Looking at … stuff.”

Singh frowned at him. “Sightseeing, in the most dangerous part of the Shanties. And this Colpeper, what was he? Tour guide? Ice-cream man? I don’t suppose he’s any relation to the Frances Colpeper we picked up last year for running an illegal salvage operation using child labour?”

Kara gulped. “We wouldn’t know anything about that.”

Singh sighed. “Employing Beefs isn’t just an offence for the men who run the gangs. The kids can find themselves in serious trouble too. A night in the cells, a tracker bracelet, even a trip to the work farms if they’re really unlucky.”

“Well, isn’t that just child labour as well?” Kara shot back before she could stop herself.

The lieutenant raised an eyebrow. “I warned you once.”

He tapped the touchscreen set into his desk, squinting. “Says here you’re Kara Jordan, fifteen years old, father a market trader, knifed in a robbery. Mother died three months later, ruled as suicide.”

“It was an accident,” Kara said. “She slipped.”

Sympathy flickered in Singh’s eyes. “You were picked up by the authorities and spent four years at the Sisterhood—”

“I won’t go back there,” Kara said quickly. “You can’t make me.”

“Calm, girl. I’m just getting my facts straight. But there’s no record of the boy at all. How old is he, eleven? Where are his parents?”

“They ran off,” Joe said. “They didn’t want me.”

“So we’re orphans,” Kara said. “What are you going to do, adopt us?”

The officer smiled despite himself. “No, but the state could. I could make a few calls, have you placed in care. It’d be a shame if you never got to see each other again.”

Kara’s chest tightened. These weren’t empty threats; Singh had the power to do exactly as he promised. But he could also let them go, drop them back in the Shanties and forget all about them.

“So tell me,” he said, leaning forward. “The truth this time. The boy’s a bottom feeder, am I right? A Beef? And this Colpeper, he’s your crew boss?”

Kara hung her head and nodded.

“But your being out there had nothing to do with the Mariners, did it?”

She looked up. Singh’s stare was intense, but there was no suspicion left in it.

“I told you,” Kara said. “It just… happened.”

The officer settled back. “I believe you. Call me a sucker, but—”

“What is the meaning of this?”

The door slammed open and a stocky, barrel-chested man came shouldering in, his face as red as a marker buoy. “Explain yourself, second lieutenant.” He wore a sharp black suit with the MetCo logo on the breast, and his light brown hair clung to his head like a shaggy animal. Kara glanced up at the portrait on the wall; it was the same man, and now she remembered his name: Alexander Remick, CEO of MetCo and head of security for the whole of London.

Singh blanched. “Sir, I didn’t… I had no…”

“Clearly not,” Remick growled. “We have a major incident on our hands and I find you tucked up indoors, chatting with a pair of filthy mudlarks. Let me assure you, minister, this is not how I train my officers to behave.”

Kara craned her neck, seeing a tall, serious-looking woman standing behind him in the corridor. She wore a grey skirt and carried a leather briefcase printed with the symbol of the crown. A government minister, Kara realised. Here in the Shanties. This must be serious.

Singh saw her too, and his jaw tightened. “Th-these are the witnesses from my report,” he stammered. “They were on site when the Mariner went into the water. The lad even spoke to him.”

Remick regarded them with icy interest. Joe stuck his hand out, but Remick just stared at it until he put it away again. “Well, young man? What did the terrorist have to say?”

Joe gulped. “H-he said he was s-sorry. I tried to h-help him, and he died.”

“Is it your habit to offer aid to insurgents?” Remick asked, leaning closer. “Are you a friend to the Mariners, boy?”

“No,” Joe squeaked. “I didn’t… He wasn’t…”

“He didn’t have a shirt with Mariner written on it,” Kara said. “How was Joe meant to know?”

Remick’s face darkened. “He was being pursued by my men. That ought to be enough.” He forced a smile, turning back to the woman. “My apologies for this slight delay, my dear minister. I just need a moment with my subordinate, so if you wouldn’t mind waiting down at the front desk we’ll have this squared away in no time.”

The minister smiled thinly. “Very well, Mr Remick. But please don’t dawdle; we have a lot to attend to.”

Remick closed the door softly, then he turned on Singh, nostrils flaring. “Do you know who that was? No? I’ll enlighten you. Her name is Patricia Stephens, she is the junior minister for defence and she is entirely capable of revoking MetCo’s contract if she doesn’t think we can handle the vital job of City security. We have surveillance footage suggesting that the Mariner was inside the Wall, Akharee. Inside. He was on his way back through the Gullet when the alarms went off.”

Singh looked stunned. “But that’s not possible.”

“And that’s not even the most pressing issue,” Remick went on. “If you’d bothered to look through your own blasted window in the past fifteen minutes, you’d see that we have another problem on our hands.”

Singh winced, turning to look down into the Pavilion. Kara angled herself, peering over his shoulder.

The Pavilion was the heart of the Shanties, a quarter-mile expanse of flat concrete that was the closest they had to a town square. It was always busy at this time of day as weary workers were spat out of the City through the Gullet, the only tunnel leading under the Wall. But tonight the crowds were bigger than ever, a mob gathering at the base of the wide stone steps that led down from the Zoo. They surged forward, a line of riot-shielded MetCo officers holding them back.

“They’re saying we allowed this to happen,” Remick spat. “That we let terrorists run loose in the Shanties. It needs to be knocked on the head before it spreads. In a few minutes I’m going to speak to them, calm things down and show the minister we’re on top of it. I could use a little backup. Honestly, Singh, her being here is the last straw; if you knew the kind of pressure I’m under…”

“I’ll be there, sir,” Singh said. “I just need to discharge these two and I’ll be right down.”

Remick straightened his tie, one hand on the door. “You’re a good man, Singh. Just try to keep your focus where it belongs in future.”

He shut the door behind him and Singh made a rude gesture. “Focus on this,” he muttered. “Sir.”

“He’s not as friendly as his picture, is he?” Joe said, peering up at Remick’s portrait. “It’s weird – the eyes feel like they’re following me.”

“There’s a camera behind the left one,” Singh admitted. “It’s one of his favourite sayings: a family watches over each other. That’s how he likes to think of us. One big MetCo family.”

“Well, he does tell you off when you’ve been naughty,” Kara pointed out.

Singh sighed. “You heard him, we’re done here. Don’t forget your possessions.” He rifled through a small polythene bag. “One torch, one bottle, one screwdriver, one … weird plastic bear.”

“I call him Growly,” Joe said.

“Good for you. But what’s this?” He took out a damp crumpled ball of white paper, unfolding it. A scrawl of black ink formed a crude oval filled with wavy lines.

A short list of words were smudged with what might have been chocolate.

“It’s just a picture,” Joe said quickly. “I drew it for school.”

“A picture? Of what?”

“Some…” Joe struggled. “Some spaghetti. See, it’s on a plate.”

“Why would you draw spaghetti?” Kara asked.

Joe looked at her intently. “I was hungry.”

“And what about these words?” Singh wondered, tracing with his finger. “Sun four, six down, news, Wellington? What does all that mean?”

“They were already on it,” Joe said. “We use old scraps at school. Haven’t you heard of recycling?” He looked at Singh, unblinking. The officer folded the paper and handed it to him.

“You’re a weird kid,” he said. “But that’s hardly a crime. OK, if you remember anything else you know where to find me. In the meantime, I’ll have your boss brought from holding. But I want you to think long and hard before you get mixed up with men like him. I know you have to eat, but there’s ways and there’s ways, understand?”

Kara held his gaze for a moment, then she nodded. “Thank you.”

Singh sighed. “Now split. I’ve got an angry mob to deal with.”

4

The Walk Home

They found Colpeper waiting by the security barrier in the Zoo. His left eye was black and his lip was split. “This has not been a good day,” he growled as they pushed through a set of high glass doors and out into the Pavilion.

At the base of the steps the mob had tripled in size, many of the protesters still wearing their brown work overalls. They churned like a muddy sea, breaking against a wall of MetCo riot shields.

Then the shouts subsided and a murmur ran through the crowd. Kara turned to see Remick emerging from the glass facade of the Zoo, Singh at his side. Just inside stood the minister, watching darkly. Above them the Wall rose, sheer and white.

“I thought it was time I came out and said a few words.” Remick spoke into a handheld microtransmitter, his voice picked up by speakers all around the Pavilion.

“It’s past time!” someone shouted, and the crowd muttered their agreement.

Remick nodded. “You’re right. I’m sorry. It’s been quite a day.”