0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

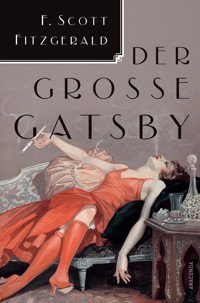

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American author of novels and short stories, whose works are the paradigmatic writings of the Jazz Age. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest American writers of the 20th century. Fitzgerald is considered a member of the "Lost Generation" of the 1920s. He finished four novels: "This Side of Paradise", "The Beautiful and Damned", "The Great Gatsby" (his most famous), and "Tender Is the Night". A fifth, unfinished novel, "The Love of the Last Tycoon", was published posthumously. Fitzgerald also wrote many short stories that treat themes of youth and promise along with age and despair. Fitzgerald's work has been adapted into films many times. His short story, "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button", was the basis for a 2008 film. "Tender Is the Night" was filmed in 1962, and made into a television miniseries in 1985. "The Beautiful and Damned" was filmed in 1922 and 2010. "The Great Gatsby" has been the basis for numerous films of the same name, spanning nearly 90 years: 1926, 1949, 1974, 2000, and 2013 adaptations. In addition, Fitzgerald's own life from 1937 to 1940 was dramatized in 1958 in "Beloved Infidel".

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 30

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Forging Ahead

Basil Duke Lee and Riply Buckner, Jr., sat on the Lees' front steps in the regretful gold of a late summer afternoon. Inside the house the telephone sang out with mysterious promise.

"I thought you were going home," Basil said.

"I thought you were."

"I am."

"So am I."

"Well, why don't you go, then?"

"Why don't you, then?"

"I am."

They laughed, ending with yawning gurgles that were not laughed out but sucked in. As the telephone rang again, Basil got to his feet.

"I've got to study trig before dinner."

"Are you honestly going to Yale this fall?" demanded Riply skeptically.

"Yes."

"Everybody says you're foolish to go at sixteen."

"I'll be seventeen in September. So long. I'll call you up tonight."

Basil heard his mother at the upstairs telephone and he was immediately aware of distress in her voice.

"Yes. . . . Isn't that awful, Everett! . . . Yes. . . . Oh-h my!" After a minute he gathered that it was only the usual worry about business and went on into the kitchen for refreshments. Returning, he met his mother hurrying downstairs. She was blinking rapidly and her hat was on backward--characteristic testimony to her excitement.

"I've got to go over to your grandfather's."

"What's the matter, mother?"

"Uncle Everett thinks we've lost a lot of money."

"How much?" he asked, startled.

"Twenty-two thousand dollars apiece. But we're not sure."

She went out.

"Twenty-two thousand dollars!" he repeated in an awed whisper.

His ideas of money were vague and somewhat debonair, but he had noticed that at family dinners the immemorial discussion as to whether the Third Street block would be sold to the railroads had given place to anxious talk of Western Public Utilities. At half-past six his mother telephoned for him to have his dinner, and with growing uneasiness he sat alone at the table, undistracted by The Mississippi Bubble, open beside his plate. She came in at seven, distraught and miserable, and dropping down at the table, gave him his first exact information about finance--she and her father and her brother Everett had lost something more than eighty thousand dollars. She was in a panic and she looked wildly around the dining room as if money were slipping away even here, and she wanted to retrench at once.

"I've got to stop selling securities or we won't have anything," she declared. "This leaves us only three thousand a year--do you realize that, Basil? I don't see how I can possibly afford to send you to Yale."

His heart tumbled into his stomach; the future, always glowing like a comfortable beacon ahead of him, flared up in glory and went out. His mother shivered, and then emphatically shook her head.

"You'll just have to make up your mind to go to the state university."

"Gosh!" Basil said.

Sorry for his shocked, rigid face, she yet spoke somewhat sharply, as people will with a bitter refusal to convey.

"I feel terribly about it--your father wanted you to go to Yale. But everyone says that, with clothes and railroad fare, I can count on it costing two thousand a year. Your grandfather helped me to send you to St. Regis School, but he always thought you ought to finish at the state university."