4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Sparkling Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

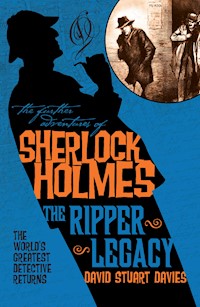

This exciting anthology brings together the work of two much admired Sherlock Holmes writers. In these stories Holmes and Watson are engaged in daring exploits applying their razor-sharp intelligence in new cases.

By David Stuart Davies

The Reichenbach Secret

The Adventure of the Brewer's Son

The Secret of the Dead

Murder at Tragere House

By Matthew Booth

The Dragon of Lea Lane

The Fairmont Confession

The Mornington Scream

The Riddle of Satan's Tooth

The Tragedy of Saxon's Gate

The Verse of Death

Reviews

"Captures the feel of the originals ... well-rounded tales" - Jonathan Johnson, Librarian, USA

"Gripping stories which capture the essence and spirit ... satisfying complex mysteries" - Neil Coombes, UK reviewer

"It is a testament to the writers ... that it is difficult to see where Doyle ends and the new authors begin ... A welcome addition to the legacy of Conan Doyle" - Tracy Colton, UK reviewer

"These stories bring Holmes and Watson back to life in the true spirit of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle." - Jeannette Beech, UK reviewer

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 348

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Further Exploits of Sherlock Holmes

The right of David Stuart Davies to be identified as the author of:

The Reichenbach Secret

The Adventure of the Brewer’s Son

The Secret of the Dead

Murder at Tragere House

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The right of Matthew Booth to be identified as the author of:

The Dragon of Lea Lane

The Fairmont Confession

The Mornington Scream

The Riddle of Satan’s Tooth

The Tragedy of Saxon’s Gate

The Verse of Death

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved

The Reichenbach Secret © David Stuart Davies 1997

The Adventure of the Brewer’s Son © David Stuart Davies 1999

The Secret of the Dead © David Stuart Davies 2014

Murder at Tragere House © David Stuart Davies 2016

The Dragon of Lea Lane © Matthew Booth 2008

The Fairmont Confession © Matthew Booth 2016

The Mornington Scream © Matthew Booth 2016

The Riddle of Satan’s Tooth © Matthew Booth2016

The Tragedy of Saxon’s Gate © Matthew Booth 2008

The Verse of Death © Matthew Booth 2015

These stories are works of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organisations, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or places is entirely coincidental.

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted by any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Cover design based on an image © Spiderstock

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

© David Stuart Davies and Matthew Booth

ISBN: 978-1-907230-61-5

There is no corresponding print edition of this title.

Reviews

“Captures the feel of the originals ... well-rounded tales”

Jonathan Johnson, Librarian, USA

“Gripping stories which capture the essence and spirit ... satisfying complex mysteries”

Neil Coombes, UK reviewer

The Reichenbach Secret

David Stuart Davies

‘Stand with me here on the terrace for it may be the last quiet talk we shall ever have.’ The words are those of my friend Sherlock Holmes. They were spoken to me on that fateful evening in August 1914 just after we had captured the German spy, Von Bork. You will find details of this adventure in His Last Bow, an account I penned myself but presented in the third person in order to achieve a more dramatic effect. As it turned out it was not the last occasion on which Holmes and I had a ‘quiet talk’. That occurred some two summers later.

I had heard little of Holmes since the capture of Von Bork and then, out of the blue, I received a note from a neighbour of his informing me of my friend’s failing health. Shocked at this news, I determined to travel down from London to his retirement cottage in Sussex to see him. I was aware that this was probably the last opportunity I would have to meet with my old friend – a last chance to say goodbye.

I wired ahead to ascertain whether my visit was possible and received an instant, impish response from Holmes: ‘Please come if convenient; if inconvenient, please come all the same.’ I travelled from London by train and hired a taxi cab from the local station to take me to his cottage. The cab dropped me by a dusty lane, at the end of which I saw a whitewashed cottage almost perched on the cliffs, overlooking the sea.

I found Holmes sitting in his garden in the afternoon sun, gazing across the great blue expanse of the English Channel. He wore a pale linen suit and a sand-coloured Panama hat and for all the world looked like a retired colonial. His face, however, was pale and gaunt and those bright eyes, although still sharp and piercing, had sunk deeper into their sockets. He rose to greet me and I found his handshake as firm as ever.

‘My dear, dear Watson, by all that’s wonderful, you are a sight for sore eyes,’ he said warmly. ‘Still practising a little medicine, I see.’

‘Why, yes,’ I replied in some surprise.

He grinned and pulled up a garden chair for me to sit on. ‘Iodine stains on the fingers and the telltale shape of a thermometer case in your top pocket.’

I chuckled gently. ‘You can still surprise me with…’

‘ … my little observations. I’m please to hear it.’ He leaned forward and rang a small bell on the table beside him. ‘I am sure that you would find a cup of tea refreshing after your long journey.’

In response to the bell, his housekeeper emerged from the cottage, took my overnight bag and set about arranging for the tea.

‘Martha is no longer with you?’ I asked when the lady had returned indoors.

‘Sadly, no. She has retired and returned to her native Scotland. ‘My old bones are not up to serving you any more, Mr Holmes.’’ he mimicked the faint Scottish tones of our redoubtable landlady.

It was a wrench to us both to lose her. She has served me well and truly.’

‘Served us both.’

Holmes paused and gave me a thin smile. ‘Served us both,’ he said softly.

How strong are the memories of that afternoon: Holmes and I sitting in the bright sunshine, drinking our tea, the faint breeze off the sea, the hum of the bees and the conversation. The conversation, which began with talk of the war but then drifted inevitably into discussions of our past cases. As is the way with old men, we relived our youth, talking of Milverton, John Clay, the Baskerville affair and countless other cases in which Sherlock Holmes and I joined together to counteract the forces of crime. Once again we were in our Baker Street rooms, hearing the distressed pleas of a desperate client or rattling through the streets in a hansom cab on our way to Paddington, Euston or King’s Cross to catch an express which would bring us to some great house in the shires where there was another mystery to unravel.

I felt pangs of sadness when we discussed the Agra treasure business, a case which brought me my own greatest treasure, Mary, my beloved wife. At first, Holmes seemed unaware of my discomfort but, as he moved on to discuss another of our adventures, he narrowed his eyes, gave me a brief nod and patted my arm.

As we talked, I felt my heart grow light and the spirit of adventure rise within my weary bones. I marvelled at the realisation of what we had done and achieved. To think that I was the companion of the man who had turned detection into an exact science.

Suddenly my friend laughed out loud. ‘The irony of it, Watson, the irony of it.’

‘I’m sorry, I don’t quite understand.’

‘You remember how I used to rail at you about your overly romantic accounts of my cases that were published in the Strand Magazine?’

‘Indeed I do.’

‘Well, now I find my memory somewhat … unreliable, so that I have had to purchase a whole bound set of the magazine in order that I can bring to mind all the details of those cases.’

‘He burst out laughing and I joined him.

We sat conversing until the sun had almost set, sending warm, crimson fingers of twilight across the still, sparkling waters.

*

That evening we dined quietly. Holmes’ new housekeeper, Mrs Towers, a local lady who didn’t live in, provided us with a simple but appetising meal and Holmes had dug out a very good bottle of Beaune from his modest cellar. The cottage was illuminated by oil lamps, electricity not yet being available in such an isolated spot. There was also a small fire lit in the dining room to ward off the chill of an English summer evening; the flames added to the soft amber glow of the chamber which, in essence, reflected my own inner glow. Here I was with the best and wisest friend I knew, chatting amiably about old times. For the moment I felt cocooned in this pleasantly primitive dwelling against the harsh realities of the terrible war which was being fought across the channel whose blue waters we had been gazing upon that afternoon.

Mrs Towers served us pudding, assured my friend that she would attend to the washing up in the morning and bid us both good night. By the time Holmes and I were tackling the brandy and coffee, we were in a very relaxed mood indeed.

Holmes lit his pipe and stared at me quite sternly for some moments. ‘I think the time is right to confide in you a secret that I have held close to my chest for a long time – something I wished I could have told you many years ago. I tell you now, my dear Watson, so that I can ask your forgiveness.’

I looked at my companion in surprise. ‘Surely, there can be nothing…’

He held up his hand to silence me. ‘Pass judgement when I have finished.’

‘Very well,’ I said, somewhat sobered by Holmes’ change in demeanour.

‘You will remember with great clarity the Moriarty case.’

‘Certainly.’

‘The way his thugs sought to kill me and how he visited me in my Baker Street chambers to warn me off? How I fled to Switzerland and he followed me? How we fought on the brink of the Reichenbach Falls? How he fell to his death in the roaring torrent and I escaped? You remember all that?’

‘As though it were yesterday.’

Holmes paused and swirled the brandy in his glass before taking a drink. ‘I was fooled, Watson. We all were. I did not actually meet Professor Moriarty for the first time until a month after the Reichenbach incident.’

‘What! But you told me that he came to see you in London.’

Holmes shrugged. ‘I believed that he did. I was a gullible fool. Someone came to see me. He told me that he was Moriarty and he bore a close approximation to the description that I had been given of the scheming professor – a description which also turned out to be false. In truth, the man who came up the seventeen steps of 221B was an impostor hired by Moriarty. Had I my wits about me at the time, I should have realised that. The great man was not going to place his own person in such danger by visiting his arch-enemy in his lair. He could not know what I would or could have done. Moriarty did not take those kinds of risks, so he sent along a consummate actor to play him. The message was genuine: it was the messenger who was a fake.’

‘I cannot believe that you were taken in by this charade.’

Holmes shook his head sadly. ‘But I was, my friend. The phrase is ‘hook, line and sinker’, I believe. But the fellow played his part well. Even now my flesh begins to creep when I consider that encounter. The trick worked beautifully, as Moriarty knew it would. He had a powerful intellect and created his own certainties out of mere possibilities. One more brutish attack from his agents and I came to realise that my best plan was to leave the country until Scotland Yard moved in on the Professor’s organisation.’

Holmes smiled. ‘And what a pleasant time we had of it – until we reached Rosenlaui.’

‘But you were aware of the shadow cast over our sojourn.’

‘Yes. I tried to protect you from it, but I knew that your sensibilities would alert you to the danger we were in. It was I who arranged for the boy to bring you the message about the dying Englishwoman at our hotel. I knew your stout heart could not refuse such a patriotic summons.’

‘You wanted me out of the way.’

‘I wanted you out of danger. I believed I was about to face my nemesis by the Reichenbach Falls. I feared the worst. But what I didn’t know – what, as a detective, I failed to deduce – was that we were being trailed by trained assassins in the pay of Moriarty, under the leadership of Colonel Sebastian Moran. And not, as I assumed, by Professor James Moriarty himself.’

I took a gulp of brandy. My mind and my senses were now clear and alert. All feelings of drowsiness and inebriation had been expelled by my friend’s narrative. Although these revelations were shocking and new, they only presented a fresh interpretation which was frighteningly plausible.

‘Where was Moriarty?’ I asked at length.

‘That comes later. Suffice it so say that he too had left London for the safety of foreign shores. You see, he was far more concerned about preserving his own life and salvaging what he could of his organisation than dealing with an irritant like me.’

‘More than an irritant, surely? It was your work which brought about the collapse of his empire.’

Holmes grinned broadly. ‘You still have a way with words and the use of a telling phrase, Watson. You are correct, of course, but Moriarty was far too intellectual to lower his sights to personal revenge. I must be removed, there was no uncertainty about that, but for a long time it was not a personal vendetta. That would be too…’

‘Emotional – and emotion clouds the intellect.’

‘Yes. You see we were twins – of a kind.’

I leaned forward on the table and gazed at my friend for some moments before I spoke. ‘Then who… who did you meet on the path above the Reichenbach Falls?’

For an instant, Holmes seemed to be overcome by a strange emotion. He closed his eyes and lowered his head. ‘In truth,’ he replied at length, ‘I do not know. He was yet another agent of Moriarty. Not the same man who visited me in Baker Street but of similar appearance. At the time, I really believed that this was the Professor Moriarty, the Napoleon of Crime, but he was not. However, I soon discovered that this fine fellow was skilled in martial arts. Never have I fought so hard and so desperately as I did on that precipitous ledge overlooking that yawning chasm. Our struggle was exactly as I reported it to you in your consulting rooms on my return to London three years later.’

‘With your knowledge of baritsu you managed to overbalance him and he fell over…’

‘That terrible abyss,’ he mouthed my own words back at me.

I did not smile.

‘You see why I found it hard to tell the truth.’

‘But these are lies upon lies. You kept me in the dark for three years – three whole years – believing you to be dead and now you are telling me that you never met Moriarty at all and did not bring about his death.’

‘I am not saying that. The truth is always darker and more complex than we would have it.’

‘Is it?’ I replied tersely, reaching for the brandy bottle and pouring myself another drink.

‘The account I gave you of my escape was true. After my opponent had dropped into the swirling waters below me, I knew I could not retreat down the path without leaving tracks. My only resort was to attempt to scale the cliff wall behind me. I struggled upwards and at last I reached a ledge several feet deep and covered with green moss where I could lie unseen. I felt I had reached the end of my dramatic adventures for that day when an unexpected occurrence showed me that there were further surprises in store for me. A huge rock, falling from above, boomed past me, struck the path and bounded over the chasm. For an instant, I thought it was an accident; but a moment later, looking up I saw a man’s head silhouetted against the darkening sky; and another stone struck the ledge within a foot of my head. The meaning was plain: another of Moriarty’s minions was on the scene. I had to act quickly unless I wished to remain an easy target. I scrambled back down on to the path. I don’t think I could have done it in cold blood. It was a hundred times more difficult than getting up. But I had no time to think of danger, for another stone sang past me as I hung my hands from the edge of the ledge. Half way down I slipped but, by the blessing of God, I landed, torn and bleeding, on the path. I took to my heels, did ten miles over the mountains in the darkness, and a week later I found myself in Florence, with the certainty that no one on the world knew what had become of me.’

‘This much I know.’

‘Then it is time I told you what you do not know.’

*

Holmes threw another log on the fading fire and it retaliated with a crackle and a spray of sparks. I sat impassively awaiting the recommencement of his narrative, unsure of my own emotions. I had believed that I had passed the stage of being surprised or angered by my friend but I had been wrong. To the end, he was an enigma. And a devilishly frustrating one.

‘Florence is a magical city. I fell in love with it at once. I may have stayed there if events had turned out differently. There is a warmth and a sense of well being there which I have seldom encountered anywhere else. Walking its streets is like coming home The light is hypnotic and those wearied sand-coloured edifices soothe and inspire.’

‘Cut the poetry, Holmes.’

Holmes raised his brows and gave me a wry smile. ‘I soon found myself lodgings and started to acquaint myself with the great city. I supplemented what money I had by selling sketches.’

‘I never knew that you could draw.’

‘Sufficiently well. I have art in my blood. You will remember that the painter Vernet was a distant relation of mine. Indeed, I was known as Martin Verner during my stay in the city. I drew the Duomo and the Ponte Vecchio countless times and sold them to eager tourists. I could have made a healthy living there had it not been for certain developments.’

‘Developments?’

‘Indeed. I had been in Florence for about a month and I had become a regular artist by the Ponte St Trinita with its exquisite statues of the four seasons – it is upstream of the Ponte Vecchio and an ideal vantage point. I was even on nodding terms with some of my fellow artists, most of whom were Italian.

‘It was late one afternoon and the tourists had not been coming to view the wonderful bridge that day. I had been alone sketching out another canvas and was thinking about packing up for the day when my concentration was broken by cries for help. The voice was that of an Englishwoman. I looked up from my easel and saw her, not fifty yards away, struggling with two swarthy fellows, footpads, I assumed. One of them was pulling at her handbag. I raced to her assistance, shouting terms of abuse at her attackers. After a month in Italy, my knowledge of the vernacular was fairly comprehensive. On seeing this tall stranger bearing down on them, the cowards fled, leaving the lady slumped on the cobbles but still clutching her bag.

‘I helped her to her feet and enquired if she were hurt. She shook her head and thanked me for my intervention. She was not a young woman, Watson, probably in her late thirties, but she was a handsome one. She possessed pale skin, iridescent blue eyes, and strongly defined features with a nose that was perhaps too large for a feminine face but which gave her features a strange attractiveness.’

‘You sound like me,’ I said.

‘The result of reading all those Strand Magazine accounts of yours, no doubt.’

Holmes puffed on his pipe and for a moment his eyes took on a dreamy, faraway look as though he was conjuring an image of this woman in his mind, and then abruptly he returned to his narrative.

‘She introduced herself to me as Hilda Courtney from London. I offered to escort the lady to her destination and she smiled. ‘My destination is a restaurant. I am only in the city for one night and I wished to experience dinner al fresco at one of the open-air restaurants here rather than the stuffy dining room at the hotel. Please join me as my guest, a small gesture to thank you for your chivalrous rescue.’ I accepted her offer and suggested we dine at Santo Spirito on the Via Michelangelo.

I can tell you, Watson, it was a delight to converse with someone English once again. The lady was spirited and intelligent and our conversation meandered through politics – British and European – the merits of Pre-Raphaelite paintings and Babbage’s computer, a subject upon which Miss Courtney was very knowledgeable.’

‘What was she doing in Florence?’

‘I was coming to that. Apparently, she was working as a courier for Carmichael’s, the auction house in Bond Street. Two weeks previously, a London agent acting for Count Mario Bava had acquired the Belvedere Stone, a precious 22 carat South African diamond at a sale and Miss Courtney was bringing it from England for him. The Count had a villa in the hills above Florence and was due to rendezvous with Miss Courtney at her hotel the following morning.’

‘You mean to say that she kept the diamond in that handbag?’

Holmes nodded.

‘Then possibly those fellows were not simply common thieves…’

‘But informed felons? The thought had struck me also.’

‘Why didn’t she leave the damned thing in the hotel?’

‘Safes in Italian hotels are notoriously vulnerable.’

‘Did she show you the Belvedere Stone?’

‘Indeed she did. Very discreetly but nevertheless I can tell you that it appeared to be a very handsome lump of carbon.’

‘Why on earth did they send a woman on such a precarious errand?’

‘Because a middle aged lady is less likely to be suspected of carrying such precious cargo than a pale-faced, dark-suited Englishman clutching a sturdy attaché case.’

‘I suppose so.’

Holmes took another sip of brandy and laughed. ‘What do you know of disguise, Watson?’

I was somewhat thrown by this unexpected question and its vague nature. I shrugged in response.

‘Clothes, various properties and subtle make up are fine,’ said Holmes. ‘I have used them all myself but to the trained eye certain natural aspects cannot be disguised.’

‘The ears,’ I suggested.

‘Quite so. The ears and the hand. And something else.’

‘Is this relevant?’ I asked.

Holmes ignored my query and returned to his narrative. ‘The time came for Miss Courtney to return to her hotel. We had talked long into the evening and I had enjoyed the occasion enormously, but the hovering waiters were hint enough that our departure was overdue. The lady insisted on paying. Gloves are a nuisance in dealing with Lire, aren’t they? Miss Courtney had to remove them to ensure that she paid correctly. It was a perfect Italian evening: warm with a faint breeze from the hills and a star-spotted blue sky…’

‘You sound like a romantic, Holmes. Don’t tell me you were falling in love with this lady?’

‘I will not tell you that. But I cannot deny that I experienced a certain … excitement in her company. We made our way back along the Ponte St. Trinita, chatting in a desultory fashion, when I heard footsteps behind us. I turned and saw three dark shadows advancing stealthily in our direction. There was no doubt that their purpose was malevolent. As they grew nearer, I saw that each carried a weapon. I knew what they were after.’

‘The Belvedere Stone!’

Holmes shook his head. ‘Oh, no. They were after me! The lady gave a cry of anguish as one of the fellows lunged at me with a stiletto.’

‘What on earth did you do?’ I asked, finding myself now sitting on the edge of my seat.

‘I did what I had to do. I grabbed Miss Courtney around the neck and pulled her in front of me to take the force of the blow.’

My blood ran cold. Could I believe what I was hearing? Did my friend, my honourable friend, really use a woman as a shield to protect himself from armed thugs? Was this the terrible secret that he had waited all these years to reveal? Was this why he had delayed his return to London and sought counsel with the head lama in Tibet? I stared at those strained, chiselled features with a mixture of disbelief and horror.

‘It was only a glancing blow and caught the creature on the wrist. Miss Courtney gave a very unladylike oath. By this time I had my own knife out and, pulling away her high scarf, I held the blade to her neck – to the slight lump in her throat, to be precise.’

‘The slight lump in the throat … My God! An Adam’s apple! She was a man!’

Undeterred by my outburst, Holmes continued his narrative. ‘I yelled at the thugs to disappear or their accomplice would die. They obeyed with remarkable alacrity.’

‘It had all been a plot to trap you.’

‘Slowly sinking in, Watson, old fellow?’

‘Moriarty’s men?’

‘Of course. Like an organism under a microscope, I had been observed closely all the time. The Professor had waited patiently until he had decided that my guard was down and then he played the most remarkable of stunts. You see, he is so like me in many ways, Watson. He cannot resist a touch of the dramatic: hiring actors to portray him and then finally, when his criminal pyramid had been reduced to dust, he came after me with typical guile and flair. No doubt he could have had me killed by hired assassins at any time in that hot, teeming city. But that would have been so impersonal. And he approached this scheme, as he did his many others, with ingenuity and originality. There were no thespian alter egos in this charade, just a cool killer dressed as a woman, a subtle diversion which might well have worked.’

I laughed aloud. ‘This is incredible,’ I cried, ‘and you will not be surprised to learn that I am utterly amazed. So, what happened?’

‘It is a simple tale to tell. The assassins having fled, left me alone on the bridge with my strange antagonist. I relaxed my guard momentarily. This was sufficient for him to slip free of my grasp and aim a blow at my face. I dodged, but his fist caught me on the jaw. I staggered backwards, my knife dropping from my hand into the dark swirling waters below. The fellow rushed at me, throwing his long arms about my body. I fell back against the balustrade and, as we struggled together, he managed to hoist me up in an attempt to tip me into the river. My head and shoulders were hanging dangerously over the edge high above the gushing torrent. It was then that I brought into play my knowledge of baritsu, the Japanese system of wrestling. I relaxed my body like a rag doll as my opponent forced me further over the edge. Believe me, Watson, I had to judge this with tremendous precision. Then, on the point of losing my balance, I stiffened my body, flexed it violently, and pulled and heaved this creature over my head. Rather like a dark shooting star, he flew past me with a piercing shriek and fell into the blackness. There was a splash and a cry. And then there was silence.’ Sherlock Holmes paused and puffed on his pipe. ‘No doubt you will find the fellow’s remains lodged on the silted bed of the River Arno in the lovely city of Florence.’

I was lost for words. I knew not how to respond to this amazing story and yet Holmes made it clear by a telling gesture that his tale was not yet complete.

‘I lodged in a large block in the Via Matteo di Giovanni,’ said Holmes, leaning forward to stir the fading embers of our fire. ‘My rooms were on the second floor and were reached by an exterior stone staircase. It was a simple and basic apartment but it was self-contained and afforded me the privacy and seclusion I needed. On the following morning, I was having my second pipe of the day and idly reading Boccacio in the original when my door opened and a visitor stood on the threshold. The figure was virtually a silhouette, like a dark angel, with the fierce morning sun rippling behind him, dispersing bright beams of light around him into my room. I could tell that he was a young man dressed in a linen suit and, as he removed his hat, his dark hair tumbled over his forehead.’

Despite the sunshine and the warm morning air, I suddenly felt a chill as I gazed on this apparition.

‘So, Mr Sherlock Holmes,’ he said softly, ‘We meet at last.’ The voice was cool, relaxed and had the sinister charm of a hissing snake.

‘Do we?’ I replied casually. ‘How can I be sure?’

The stranger allowed himself a dry chuckle. ‘Oh, you will have to take my word for it but I assure you that there is no deception on this occasion. I really am Professor James Moriarty.’

I believed him. I strained my eyes to get a better look at him, but his face was in deep shade with the yellow light of the sun in bright relief behind him. But I could tell that he was young, Watson. Some ten years younger than I. Here was no ancient professor with a balding pate and stooped shoulders – that was all a hoax.

‘Why are you here?’ I asked.

‘To congratulate you and to warn you.’

I said nothing but waited for him to explain.

‘You are a remarkable man, Mr Holmes. It has almost been a pleasure to encounter your opposition – an intellectual pleasure, you understand. However, now I am tired of the game – a game which you have come very close to winning.’

‘With your organisation in ruins and your need to flee the country, I would say that I was the winner.’

Moriarty responded quickly to my jibe, but the voice remained calm and unruffled. ‘The game is far from over, Mr Holmes. It is true that there must be some years spent in the wilderness – for both of us. But in due course, like the phoenix, I shall rise. For the present I think it is time that I enjoyed my riches and travelled the world. So resilient have you been in foiling my little plans that I have decided to leave you alone. I admire your brain and have no wish to harm you now. There would simply be no point, so I can assure you that there will be no further attempts on your life or liberty. You may cease looking over your shoulder.’

He paused for effect. When I failed to reply he continued in a more business-like tone. ‘But this must be a reciprocal arrangement. You must eliminate from your mind all thoughts of revenge or plots to bring me to justice. As far as the world at large is concerned, they must believe that I perished at the bottom of the Reichenbach Falls. And just to make sure that you accept these conditions, I have arranged for a watch to be placed upon Dr Watson. Dear Dr Watson, your closest friend and ally.’

I felt my hands gripping the arms of the chair in impotent anger as the devil unveiled the details of his plan.

‘If I even hear or suspect that you are making enquiries about either my whereabouts or my plans, I will arrange for the good doctor to meet with an accident – something suitably nasty.’

I jumped to my feet, the chair tipping over behind me, and was about to pounce on him when he flashed a revolver at me. I heard the click of the hammer being cocked.

‘Now, do not act in haste or anger, Mr Holmes. Should anything befall me here, Watson will be dead within twenty-four hours. Not all my colleagues were arrested, you know. There is a slender framework to my organisation still in place in London. Be sensible. Leave me alone and I will leave you and the good Watson alone. One false step and … well, need I go into detail?’

‘I was lost for words, Watson, and, indeed, words were useless on this occasion. There was nothing I could say or do. In that sense, he remained the victor. Whatever success I had in destroying his organisation, when the dust settled he still held the upper hand. A wave of fury surged through my veins but I was incapable of action.’

‘We will have our time in the wilderness, but in due course we shall return to our respective professions. It has been good to know you, Sherlock Holmes, but I hope that we never meet again.’

Without another word, he turned, pulling the door quickly behind him, cutting out the bright sunlight and plunging the room into comparative shadow.

I stood for some time staring at the door, my mind turning over his words. For all my cleverness, I had been placed in a situation where I could do nothing. I could not risk your life to pursue him further.’

‘If only I had known … I am an old campaigner, after all. I could have looked after myself,’ I said with some passion.

‘Against a foe that was visible and recognisable, I am sure you could. But not against Moriarty. Remember airguns, Watson? One cannot be prepared for the unforeseen.’

‘Why didn’t you tell me?’

‘I could not. I knew how you would react – much as you are doing now. I had to keep it a secret. I could not risk the consequences of such indiscretion.’

Despite my sense of disappointment and uncertain emotions, I knew in my heart that Sherlock Holmes had taken the only course of action open to him.

‘I understand,’ I said at length and then added, ‘What became of Moriarty?’

‘He never quite revived his organisation but some years later he commenced operations again in London for a short time. Although I never became actively involved in the investigation of his crimes, mainly robberies, I did pass on information about them to Scotland Yard recently. Then there was silence. Whether he is dead or he just grew weary of his calling and has retired I cannot say.’

Holmes and I sat in silence for some time. Eventually, it was my friend who spoke.

‘I hope you can forgive me, Watson.’

As I responded, I felt the prickle of tears in my eyes. ‘I can forgive you. Of course, I can forgive you. I only wish…’

‘I know, I know.’

We both smiled, but they were mirthless smiles.

I drained my glass and sighed. It was a sigh for lost opportunities, for the passing of a lost world and for the final revelation in my long relationship with Sherlock Holmes.

‘I think, said I, stretching my weary limbs, ‘it is long past my bedtime. I am not as young as I believe I am.’

*

Neither of us mentioned the Reichenbach secret again. At breakfast the following morning, it was as though nothing had been said the night before. As we sat with our coffee and toast, with Mrs Towers bustling around us, our conversation did not flow very easily and to be honest I was relieved when my hired car came to collect me at eleven. We stood, Holmes and I, for the last time, at his wooden gate, shaking hands and smiling. We both knew that our paths would never cross again and so it was with some difficulty that we parted. ‘Thank you for everything,’ I said.

Holmes smiled faintly, leaning on his stick for support. ‘It wouldn’t have been the same without you, Watson.’ It would not have been the same.’

As the car sped away and I turned to wave through the rear window, the spare figure of my old friend was already fading into the distance.

The Adventure of the Brewer’s Son

David Stuart Davies

I woke one morning in the February of 1889 to find London enveloped in the thickest fog of the winter. Pedestrians were glimpsed as mere phantoms slipping in and out of grey dense eddies, while ghostly unseen cabs clip-clopped eerily down Baker Street.

‘Pickpockets’ weather,’ observed Holmes from the breakfast table, as I gazed out of our sitting-room window at the seething fog without.

‘Even those villains may have difficulty seeing which pocket to pick in this stuff’, I said, joining my friend.

He gave me a wry grin. ‘Fog is unpredictable and so is only of use to the petty criminal. No notable villain would rely on it and therefore it is bad for business. Not only does it hold up the important crime from being committed, but it prevents the client from reaching our door.’

As if providing an ironic counterpoint to Holmes’ statement, the doorbell rang downstairs. ‘And then again,’ he continued with a sardonic lift of the eyebrow, ‘I could be wrong’.

He was indeed wrong and within minutes we had a client sitting by our cheery fire, sharing a cup of hot coffee with us and telling us his tale. He was a smartly dressed youth, with dark good looks, a broad, open face and brown, sensitive eyes.

‘My name is Matthew Whitrow,’ he began in a clear but hesitant voice. ‘I hold a position in the family firm of brewers. I live with my Uncle Godfrey Whitrow. He is in essence my guardian until I reach the age of twenty-one in two months’ time. My mother died in childbirth and my father was carried off by enteric fever while on a trip to India three years after I was born. My Uncle Godfrey, who was my father’s partner in business ‒ The Whitrow Brewery ‒ took me in and brought me up as if I were his own. Oh, Mr Holmes, I shall be eternally grateful to him for his generosity and his kindness over the years. It has not been easy for him, running the business, educating his nephew and maintaining The Grange, a large house in Pinner.’

‘Your uncle is not married?’ asked Holmes.

The youth afforded himself a little smile. ‘Good heavens, no. Uncle is a confirmed bachelor. I love him dearly but, I have to admit, he is somewhat frosty in his dealings with people, particularly women whom he considers to be very much the weaker sex.’

My friend nodded with restrained enthusiasm and indicated that our visitor should resume his narrative.

‘When I completed my education, I was given a position, a junior position, at the brewery with the understanding that eventually I should become a partner with Uncle Godfrey when I reached my twenty-first birthday. Those were the instructions left in my father’s will.’

‘And this birthday takes place in two months’ time?’ I said, checking my notes.

‘Yes, on April the sixth.’

‘So where lies your problem, Mr Whitrow?’ asked Sherlock Holmes, leaning back in his chair and lighting a cigarette.

‘I have begun to fear for my life, Mr Holmes. Three times in as many days I have narrowly escaped death.’

‘Really,’ replied my friend languidly, but his eyes shone with interest.‘ Pray give me the details.’

‘On Monday a large section of masonry fell from the roof of our house as I was leaving. It crashed to the ground only a few feet away from me. Yesterday, on the way to the office, I was chased by a gang of roughs who, I am sure, would have killed me if I had not managed to give them the slip.’

‘Why should they wish to do that?’ I asked.

Our client gave a shrug of the shoulder. ‘I have no idea.’

Holmes leaned forward and pointed a bony finger at our client. ‘There is one other incident to relate. It concerns something which happened in the early hours of the morning, something which caused you to leave the house in a hurry ‒ your shoes are unpolished, your tie is askew and you have cut yourself in four places while shaving ‒ something more perilous than the other occurrences, something which has brought you in desperation to my door.’

‘Y