Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

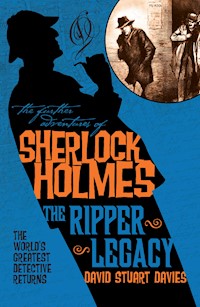

Sherlock Holmes attends a seance to unmask an impostor posing as a medium: Sebastian Melmoth, a man hell-bent on obtaining immortality after the discovery of an ancient Egyptian papyrus. It is up to Holmes and Doctor Watson to stop him and avert disaster... The action moves from London to the picturesque Lake District as Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson once more battle with the forces of evil.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 281

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SHERLOCKHOLMES

THE SCROLL OF THE DEAD

DAVID STUART DAVIES

TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE SCROLL OF THE DEAD

ISBN: 9781845869126

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

First Titan edition: October 2009

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 1998, 2009 David Stuart Davies.

Visit our website:

www.titanbooks.com

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive Titan offers online, please register as a member by clicking the ‘sign up’ button on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed in the USA.

AVAILABLE NOW FROM TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE ECTOPLASMIC MAN

Daniel Stashower

ISBN: 9781848564923

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

DR JEKYLL AND MR HOLMES

Loren D. Estleman

ISBN: 9781848567474

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE MAN FROM HELL

Barrie Roberts

ISBN: 9781848565081

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE SCROLL OF THE DEAD

David Stuart Davies

ISBN: 9781848564930

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

SÉANCE FOR A VAMPIRE

Fred Saberhagen

ISBN: 9781848566774

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE SEVENTH BULLET

Daniel D. Victor

ISBN: 9781848566767

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE STALWART COMPANIONS

H. Paul Jeffers

ISBN: 9781848565098

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE VEILED DETECTIVE

David Stuart Davies

ISBN: 9781848564909

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

Manly Wade Wellman & Wade Wellman

ISBN: 9781848564916

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE WHITECHAPEL HORRORS

Edward B. Hanna

ISBN: 9781848567498

COMING SOON FROM TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE ANGEL OF THE OPERA

Sam Siciliano

ISBN: 9781848568617

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE GIANT RAT OF SUMATRA

Richard L. Boyer

ISBN: 9781848568600

ToFreda & TonyCherished Chums

Contents

Narrator’s Note

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Epilogue

Narrator’s Note

The details of several incidents in this complex investigation only came to my knowledge once the case was closed. Using the information that was furnished to me, I have taken the liberty of dramatising these incidents in order that the reader may be presented with a coherent and cohesive narrative.

John H. Watson

Prologue

Fate has a strange way of creating a series of events which initially appear to be in no way connected and yet which, with hindsight, can be discerned as cunning links in an arcane chain. My friend, Mr Sherlock Holmes, was usually very astute not only in observing, but also in predicting these matters. Indeed, it was part of his skill as a detective. However, in the affair of the Scroll of the Dead even he, at first, failed to see the relationship between a weird and singular set of occurrences which involved us in one of our most challenging cases.

To relate the story in full, I must refer to my notes detailing a period some twelve months prior to the murders and the theft of the Scroll. The first link in our chain was forged in early May, the year following Holmes’ return from his wanderings abroad after the Reichenbach incident. It was a dark and dismal Tuesday, as I remember it: one of those days which makes you think you have been deceived by the previous day’s sunshine and that spring has not really arrived after all. I had been at my club for most of the afternoon playing billiards with Thurston. I left at five, just as the murky day was crawling its way to solemn evening, and returned to Baker Street. I poured myself a stiff brandy, a compensation for losing so badly to Thurston, and sat opposite my friend beside our fire. Holmes, who had been turning the pages of a newspaper in a desultory fashion, suddenly threw it down with a sigh and addressed me in a languid and casual manner.

‘Would you care to accompany me this evening, Watson?’ he murmured, a mischievous twinkle lighting his eye. ‘I have an appointment in Kensington, where I shall be communicating with the dead.’

‘Certainly my dear fellow,’ I replied easily, sipping my brandy and stretching my legs before the fire.

Holmes caught my impassive expression and burst into a fit of laughter. ‘A touch, an undeniable touch,’ he chortled. ‘Bravo, Watson.

You are developing a nice facility for dissembling.’

‘I have had a good teacher.’

He raised his eyebrows in mock surprise.

‘However,’ I added pointedly, ‘it is more likely that I am growing used to your outrageous statements.’

He beamed irritatingly and rubbed his hands. ‘Outrageous statements. Tut, tut. I speak naught but the truth.’

‘Communicating with the dead,’ I remarked with incredulity.

‘A séance, my dear fellow.’

‘Surely you are joking,’ said I.

‘Indeed not. I have an appointment with Mr Uriah Hawkshaw, medium, clairvoyant, and spiritual guide, this very evening at nine-thirty sharp. He assures me that he will endeavour to make contact with my dear departed Aunt Sophie. I may take along a friend.’

‘I was not aware you had an Aunt Sophie... Holmes, there is more to this than meets the eye.’

Astute as ever,’ Holmes grinned, as he slipped his watch from his waistcoat pocket. ‘Ah, just time for a wash and a shave before I leave. Are you game?’

* * *

Some time later, as we rattled through the darkened London streets in a hansom, Holmes offered the proper explanation for this evening’s strange excursion.

‘I am performing a favour for my brother, Mycroft. A member of his staff, Sir Robert Hythe, has recently lost his son in a boating accident. The lad was the apple of his father’s eye and his death has affected Sir Robert badly. Apparently he was just coming to terms with his tragic loss, when this Hawkshaw character contacted him and claimed that he was receiving spirit messages from the boy.’

‘What nonsense!’

‘My sentiments too, Watson. But to a grieving father such claims are straws grasped instinctively. In despair, logic is forgotten and replaced by wild hopes and dreams. Apparently Mr Uriah Hawkshaw is a most convincing rogue...’

‘Rogue?’

‘So Mycroft believes. He is one of these Spiritualist charlatans who milk the weak and the bereaved of their wealth in return for a gobbledegook puppet show. Mycroft is concerned as to how far this situation may develop. Hythe is privy to many of the government’s secrets and, purely on a personal level, my brother is keen that the fellow should not be misled any further.’

‘What is your role in the matter?’

‘I am to unmask this ghost-maker for what he is – a fraud and a cheat.’

‘How?’

‘Oh, that should be easy enough. According to my research there are many ways in which these individuals can be exposed. Really, Watson, it has been a most instructive venture. I have thoroughly enjoyed delving into this dark subject. My studies have led me down several learned and diverse avenues, including a visit to Professor Abraham Jordan, expert in the languages of the North American Indian. It is now clear to me that in order for the unmasking to be achieved convincingly, it has to be done while the dissembler is about his nefarious business – in performance, as it were – with his unfortunate victims in attendance.’

‘Sir Robert will be present this evening?’

‘Indeed. These entertainments are not exclusive. The vultures assemble many carrion at one sitting for their pickings. I am Ambrose Trelawney by the way. My beloved Aunt Sophie passed away just over a year ago. No doubt tonight I shall receive a message from the old dear.’ Holmes chuckled in the darkness.

I did not share my friend’s amusement in this matter. Not for one moment did I countenance the existence of these roving spirits with an appetite to communicate with the carnate world, but at the same time I sympathised, indeed empathised, with those sad creatures who, in the depths of despair at losing someone dear to them, stretched their arms out into the darkness for solace and comfort. Holmes, it seemed, had not contemplated the psychological damage that could be incurred by the destruction of such beliefs. In common with these charlatans, he was only concerned with his own magic. For myself, as I sat back in the swaying cab, I could not help but think of my own dear Mary and what I would give to hear her sweet voice again.

Within a short time we were traversing the select highways of Kensington. As I gazed from the window of the cab at the elegant houses, Holmes caught my train of thought.

‘Oh yes, there is money in the ghost business, Watson. Mr Hawkshaw lives the life of a wealthy man.’

Moments later we drew up in front of a large Georgian town dwelling which bore the name ‘Frontier Lodge’ on a brass plaque on the gate post. Holmes paid the cabby and rang the bell. We were admitted by a tall negro manservant of repellent aspect attired in an ill-fitting dress suit. He spoke in a harsh, rasping tone as though he had been forbidden to raise his voice above a whisper. He took our coats and showed us into ‘the sanctum‘: this was a gloomy room at the back of the house, illuminated only by candles. As we entered, a gaunt, sandy-haired man in his fifties came forward and grasped Holmes’ hand.

‘Mr Trelawney,’ he said in an unpleasant, unctuous tone.

Holmes nodded gravely. ‘Good evening, Mr Hawkshaw,’ he replied in a halting manner, bowing his head briefly as he spoke.

The performance had begun.

‘I am so glad that my secretary was able to accommodate you at our sitting. The vibrations have been building all day; I sense that we shall make some very special contacts this evening.’

‘I do hope so,’ replied Holmes with a trembling eagerness.

Hawkshaw glanced quizzically at me over my friend’s shoulders. I saw in those watery orbs a kind of steely avarice which disgusted me. ‘And this is...?’ he enquired.

Before I had chance to respond, Holmes answered for me. ‘This is my manservant, Hamish. He is my constant companion.’ Holmes smiled sweetly in my direction and added, ‘But he does not say very much.’

With as much grace as I could muster, I gave Hawkshaw a nod of acknowledgement, before glowering at Holmes, who ignored my glance and continued to beam warmly.

‘Let me introduce you to my other... visitor.’ Hawkshaw hesitated over the last word as though it was not quite the appropriate term to use but, on the other hand, he was well aware that the term ‘client’ would sound gauche and mercenary. He turned and beckoned from the shadows a lean, distinguished-looking man with a fine thatch of grey hair and a neat military moustache.

‘Sir Robert Hythe, this is Mr Ambrose Trelawney.’ Holmes shook Sir Robert’s hand and the knight lowered his head in vague greeting. With a distracted air, Sir Robert shook my hand also, but Hawkshaw failed to proffer an introduction. It was clear that as a mere manservant, and not a wealthy client, I was of little importance to the medium.

‘We have great hopes of reaching Sir Robert’s son tonight,’ crooned Hawkshaw, his face mobile and sympathetic, with eyes that remained cold and stony.

‘Indeed,’ remarked Holmes quietly, observing Sir Robert closely. The man was obviously embarrassed by Hawkshaw’s statement and his sensitive features registered a moment of pain before they fell once more into vacant repose. I had heard something of Sir Robert’s notable military and political career and therefore it struck me as odd, incongruous even, that this courageous, decent, and astute individual should have fallen so easily into the avaricious clutches of a creature like Hawkshaw. Such, I supposed, was the weakening power of grief that it dulled one’s reasoning faculties.

As there came an uneasy pause in the stilted conversation, the door swung open and a dark-haired woman in a wine-red gown entered and hurried to Hawkshaw’s side. ‘My dear, our final guest has arrived.’

The medium beamed with pleasure and turned, as did we all, to gaze upon the stranger who stood on the threshold of the room. He was a young man, not yet out of his twenties, tall and with a certain plumpness of face. He was dressed in a black velvet jacket, with a large floppy bow at the neck, and his long blond hair flowed down to touch the collar of his jacket.

‘Gentlemen,’ said Hawkshaw grandly, ‘allow me to introduce Mr Sebastian Melmoth.’

The pale youth’s face twisted into a thin smile of greeting. I had heard something of this Melmoth. He had the reputation of being a dissolute dandy, one of the effete admirers of the decadent Oscar Wilde. There were tales of his indulgences in various unpleasant acts of debauchery even rumours that he had dabbled in the Black Arts and other such abominations – but this was the gossip at my club in the late hours when the billiard cues were back in their racks and the cigars and brandy were being savoured. Looking upon that soft, alabaster face now, sensitive, almost beautiful in the dim light, it seemed to have all the vulnerability and expectancy of youth; but there was something about the large fleshy lips and arrogant sneer which suggested cruelty and disdain.

Perfunctory greetings were exchanged and I briefly held Melmoth’s cold, languid flesh as we shook hands. Unlike Holmes, I often judge my fellow man not by the coat cuff or the trouser knee, but by instincts; and, irrational as instincts may seem to my scientific friend, I know that not only did I neither like nor trust Mr Sebastian Melmoth, I also sensed that there was something intrinsically evil about him.

Mrs Hawkshaw, for she it was in the wine-coloured dress, placed a wax cylinder on the gramophone, and the faint, ethereal music of some composer unknown to me wafted into the air. All but one candle was extinguished and we were invited to take our places. The medium himself sat at the head of the table on a dark, ornate carver chair shaped like some medieval throne. His wife was seated beside him: I was next to her, then Sir Robert, Holmes, and by him, Melmoth.

There was a minute’s silence during which no one spoke. We sat mute and expectant in the Stygian gloom. Despite the one yellow prick of flame, my eyes could make out little but the pale, strained and expectant faces around the table. Eventually, the scratchy music died away and Mrs Hawkshaw addressed us.

‘Gentlemen, tonight my husband will attempt to go beyond the frail boundaries of this earthly life and contact our loved ones who have departed their carnate bodies.’ She spoke in flat, monotonous tones as though reciting some dirge. It took me a good deal of effort to contain my indignation at such nonsense.

‘I cannot stress too highly that it is imperative you do exactly as I say,’ she continued, ‘otherwise this meeting will end in failure and you could endanger the life of my husband.’

I glanced up at Hawkshaw. He seemed to be asleep, eyes closed, head lolling on his chest.

‘Now, please place your hands on the table and hold hands with those sitting either side of you.’ She paused while we obeyed in silent unison.

‘Thank you. Now we must wait a while for the spirit guide to come through.’

Sitting in the wavering gloom, I contemplated this ridiculous situation: how sad it was for those individuals who could not accept death’s final victory, and how despicable it was for characters like Hawkshaw to exploit their weakness for coin.

We seemed to be sitting there for some ten minutes, listening only to the heavy breathing of Hawkshaw. Indeed, I felt my own eyelids drooping and my body beginning to surrender to sleep also when, suddenly in the darkness, there came the sound of birdsong. It was clear and definite and so close that I could imagine some feathered creature fluttering in a circle around the table, its wings wafting near our faces. The sound was accompanied by a distinct chill in the air which filled the room. The candle guttered wildly, throwing distorting shadows across the pale features of my companions. It gave the eerie impression that their faces were somehow melting, changing and being re-shaped. The intense atmosphere and the darkness were playing tricks with my imagination, as surely they were designed to do. I breathed deeply and shook my head to rid myself of such unpleasant and unrealistic images.

At length, the birdsong died away. As it did so, the gramophone started up once again, filling the chamber with its weird, crackly melody. As we were all holding hands, some unseen force must have set the machine in motion.

‘The spirits are working,’ intoned Mrs Hawkshaw, as though in answer to the question that was on my lips.

By the feeble glow of the solitary candle, I discerned that the faces of the others were intense, none more so than Holmes, who peered determinedly into the darkness beyond the frail amber pool of illumination. It was as though he expected to see something in the shifting shadows – something tangible. And indeed he did. We all did. There was a strange rustling noise and then I glimpsed in the candlelight a flash of metal. Moments later it came again and then there materialised, hovering over Hawkshaw’s head, what appeared to be a brass horn. It shimmered like a mirage in the flickering light.

I glanced back at Holmes: at first a cynical smile had touched his lips, but now he seemed disturbed by what he had seen. His look of concern struck a note of unease in my own breast. Had I been wrong all along to scoff at such matters? Could the dead really communicate with us, the living? My hands grew clammy at the thought.

The horn hovered in the air for a time, moving gently above Hawkshaw’s head; then it slowly receded into the darkness, disappearing from sight.

‘The spirits are ready to speak,’ Mrs Hawkshaw informed us in a hushed monotone.

This simple statement with its awful import struck fear into my heart. The certainties with which I had entered the room had slowly dissipated. I had witnessed inexplicable phenomena and sensed the world of the unreal. What, I wondered, was next?

Hawkshaw, who had been like a dreaming statue, suddenly jerked upright, his eyes wide open and his nostrils flaring. A gagging sound emanated from his mouth and then he bellowed in a deep, dark, alien voice, ‘What is it you want from me?’

Hawkshaw answered the question in his own voice. ‘Is it Black Cloud?’

There was a pause before the reply came: ‘I am Black Cloud, a Chief of the Santee tribe, warrior of the great Sioux nation.’

‘Are you our spirit guide for tonight?’

There was a moment’s hesitation in this macabre conversation before the strange voice emerged from Hawkshaw once more, his lips hardly moving. ‘There are many here who are content and are at peace. They have no messages for the other world.’

‘Black Cloud, please help us again as you have done in the past. Our dear friends in the circle here have lost loved ones. They need comfort. They need reassurance.’

‘Who is it you seek?’

Mrs Hawkshaw turned to Sir Robert and indicated that he should speak.

With an eagerness which showed no restraint, Sir Robert leaned over the table towards Hawkshaw. ‘Nigel. I wish to speak to my son Nigel.’

There was a long pause. I felt my own nerves tensing with expectation, and then there came a sound, soft and gentle like the rustling of silk: as though someone were whispering in the darkness.

‘Nigel?’ barked Sir Robert in desperate tones.

‘Father.’ The response was muffled and high-pitched, but unmistakably that of a youth.

A look of surprise etched itself upon the features of Sherlock Holmes. His face slightly forward, he peered desperately into the darkness.

‘Nigel, my boy, is it really you?’

‘Yes, father.’

Sir Robert closed his eyes and his chest heaved with emotion.

‘Don’t mourn for me, father,’ the epicene voice advised him. ‘I am happy here. I am at peace.’

Tears were now running down the knight’s face as he struggled to keep his strong emotions in check.

‘I must go now, father. Come again and we shall talk further. Goodbye.’ The voice faded and the whispering returned briefly, before that ceased also.

‘Nigel, please don’t go yet. Stay, please. I have so many questions to ask. Stay, please.’

‘The spirits will not be bidden by you. Be content you have made contact. There will be other times.’ It was Black Cloud speaking once more.

Before Sir Robert could respond, Holmes addressed the medium. ‘Black Cloud, may I ask a question?’

There was an abrupt silence before there was a reply. At length it came in the same dark, stilted delivery. ‘You may ask.’

‘Black Cloud, you are a chieftain of the Santee? Is that correct?’

‘I am.’

Holmes then spoke in a tongue I had never heard before: a guttural, staccato dialect which he enunciated with great deliberation. I presumed that he was speaking the language of the Santee.

When he finished there was an uneasy pause. Holmes repeated a few words in this strange tongue and then reverted to English. ‘Come now, do not tell me that you fail to comprehend the tongue of your race,’ he prompted with cold authority.

There was no reply from Black Cloud.

‘Perhaps then I had better interpret for you. I called you an unscrupulous fraud, Hawkshaw. I detailed the methods by which you achieved your tawdry tricks...’

‘Mr Trelawney please...’ This interruption came from Sir Robert.

‘Bear with me, sir. Is it not suspicious that a Santee could not understand his own native tongue, the language in which I addressed him?’

As Holmes spoke, Hawkshaw fell head first on the table as in a faint.

‘Now see what you have done,’ cried the man’s wife, leaning over her husband.

‘Another diversionary tactic, I have no doubt,’ snapped Holmes, leaping from his seat. ‘Let us throw some light on the matter, shall we? I noticed the electric switch earlier...’ With a deft movement, he flooded the room with bright light. The rest of us were too stunned to move as he swept past the table and pulled back the drapes to reveal the negro manservant cowering there, clasping the brass horn we had earlier seen floating in the air. Behind him the French windows were open. Holmes closed them quickly to prevent the servant’s escape.

My friend turned to face us, a grin of triumph on his lips. ‘I am sure you all felt the chill at the start of the séance. A window left open is the simple explanation. As for the whispering, the self-operated gramophone, and the floating horn, our friend here simply stepped through the curtains and made the noises, set the machine in motion, while with his black gloves he held the horn where it might be seen and he would not. Isn’t that correct?’

The negro, with downcast head, mumbled his agreement.

As for the rest, a facility for mimicry and ventriloquism are Mr Hawkshaw’s only talents. You will admit, Sir Robert, that the voice you heard did not sound very like your son.’

The knight, whose face was drawn and haggard in the bright light, appeared to be in state of shock. ‘I suppose... I wanted it to sound like Nigel.’

‘Indeed. Wish-fulfilment is the greatest ally of these charlatans.’

‘How dare you!’ screamed Mrs Hawkshaw, stroking her husband’s head. ‘See how you’ve affected him with your slander.’

‘I am sure he will make a full recovery,’ snapped Holmes, grabbing the collar of Hawkshaw’s jacket, jerking him off the table, and slapping him heartily on the back. As he did so, a small metallic object flew from the medium’s mouth. ‘He’s just swallowed one bird too many.’

I picked it up and examined it.

A cunning device: it’s a bird warbler – hence the aviary sounds we experienced earlier.’

‘You’ve been damned clever, sir,’ observed Sebastian Melmoth smoothly, lighting up a little black cigar. ‘You’ve performed a great service for us all.’

Holmes gave a little bow and then turned to the medium and his wife who, struggling to come to terms with their exposure, were hugging each other in miserable desperation. ‘Now, I suggest you return any monies you have received from these gentlemen, and then it is time to shut up your fake show for good. If I hear of you practising your despicable charades again, it will become a police matter. Is that understood?’

Almost in unison the Hawkshaws nodded dumbly.

Melmoth chuckled merrily. ‘You put on a fine show yourself, Mr Trelawney Bravo.’

Holmes smiled coldly. ‘In this instance, the deceivers have been deceived. I am not Mr Trelawney. I am Sherlock Holmes.’

It was a week later when a strange coda to this episode was played out in our Baker Street rooms. It was late, about the time when a man thinks of retiring to bed with a good book. Holmes had spent the evening making a series of notes for a monograph on the uses of photography in the detection of crime and was in a mellow mood. A thin smile had softened his gaunt features during his preoccupations. I was about to bid him goodnight, when our doorbell rang downstairs.

‘Too late for a social visit. It must be a client,’ said Holmes, verbalising my own thoughts.

Within moments there was a discreet knock at our door and our visitor entered.

It was Sebastian Melmoth.

He was dressed very much in the manner in which we had seen him last and he was clutching a magnum of champagne. Holmes bade him take a seat.

‘I am sorry to visit at so late an hour, but it has been my intention for some days to call upon you, Mr Holmes, and this has been my first opportunity.’

My friend slid down in his seat and placed his steepled fingers to his lips. ‘I am intrigued,’ he said lazily.

Melmoth, almost ignoring my presence, raised the magnum as though it were a trophy. ‘A little gift for you, Mr Holmes, in gratitude.’ He placed it at my friend’s feet.

Holmes raised a questioning eyebrow.

‘For exposing that scoundrel, Hawkshaw. I had heard so many good accounts of the fellow that I really believed that I had found the genuine article at last.’

‘Your thanks are misplaced, Mr Melmoth. You are neither poor nor bereaved, and therefore any benefits that you received from my little performance at Frontier Lodge are purely coincidental.’

Melmoth’s icy cold blue eyes flashed enigmatically and he leaned forward, the young, plump face demonic in the shadow-light. ‘Money means little to me, Mr Holmes; and you are quite correct. I am not – at present – bereaved. However, I am most serious in my research, and you have successfully sealed up one avenue of investigation for me.’

I could retain my curiosity no longer. ‘May I ask exactly what kind of research you pursue?’ I enquired.

Melmoth turned to me as though he had only just become aware of my presence. ‘Research into death,’ he said softly. ‘The life beyond living.’

My puzzled expression prompted him to expand on his reply.

‘I am of the new age in scientific thinking, Doctor Watson. Death is a medieval mystery, a mystery that can be solved – must be solved. I do not believe that we scrape and scrabble our way along the weary road of life merely to fade into oblivion upon reaching the end. There is more. There must be more. Like Oliver Lodge and those of his persuasion, I believe that life, as we know it, is just the beginning – the starting point. I talk not of Heaven as prescribed by the scriptures, that fairyland in the sky but of a door through which we pass into immortality.’

Warming to his exposition, with flushed cheeks and tense jawline, he rose and threw his arms wide. ‘Take a walk into the East End of this city gentlemen. See the poverty there, the suffering, the open degradation. Human beings living and behaving like animals in the filth and squalor. Is that Life? Come, gentlemen, there has to be more. There is a key. Somewhere there is a key to unlock the secret of it all. You, Mr Holmes, deal with the ills of society; you, Doctor, minister to the ailments of the body. So be it; but I search beyond those petty concerns.’

‘You believe that you can alter the natural course of events?’ said Holmes.

Melmoth shook his head. ‘What you talk of as being natural is only regarded as such out of ignorance. Death is natural, I grant you, but the end of living is not. That the state of being ceases with the arrival of the burial casket is accepted by the naive, because it has never been challenged. No illness known to man would have been cured if someone had not challenged it. We would still be living in caves had there not been those who challenged the accepted beliefs and pushed the boundaries forward. I do not believe death is the end. Its power can and will be conquered.’ Suddenly he stopped in mid-flow, as though he realised that perhaps he had said too much. His face broke into a wide, unpleasant smile and his voice dropped to a sibilant whisper like a hissing snake. I assure you, gentlemen, I am correct.’

With this parting remark, he bowed low in a theatrical manner and swept from the room.

‘The fellow is mad,’ I said, as I heard him clatter down our stairs.

Holmes stared at the burning embers in the grate. ‘If only it were as simple as that, Watson.’

One

AN INSPECTOR CALLS

It has often been said – indeed, I have been one of those who have said it – that Sherlock Holmes, the famous consulting detective, was the champion of law and order of his age. However, on reflection, I can state that this is only partly true. Crime did indeed fascinate Holmes, but when it came to the solving of it, he was very selective. I have been present when he has rejected numerous pleas and entreaties to tackle a particular mystery solely on the basis that it was simply not interesting enough. The misdemeanours that intrigued my capricious friend had to bear the hallmark of the recherché before he would contemplate involving himself in providing a solution. He loved detective work for its own sake, but the detective work had to pose an unusual conundrum or it presented no challenge.

So it was in the spring of 1896 when, after a very fallow period, he devoured news of criminal activity reported in the daily press in the hope of spotting some intriguing puzzle to satisfy his needs. I would aid him every morning in this pursuit by pointing out what I regarded to be crimes of intellectual interest.

‘What you may consider stimulating to the deductive brain, Watson, falls far short of my ideal,’ he would comment disparagingly. “Music Hall Artiste Strangled In Dressing Room” poses no cerebral challenge whatsoever. A case of jealousy and intoxication. No doubt even the Scotland Yarders could cope with that one in a day!’

‘Have you seen the report in The Chronicle of the murder of Sir George Faversham, the noted archaeologist?’

Holmes took his pipe from his mouth and paused. ‘Items stolen from the family home?’

‘Nothing of real value taken.’

Ah,’ he scoffed. ‘Common burglary with homicidal consequences.’

I threw down the paper. ‘I give up,’ I cried. ‘There is obviously nothing that will satisfy you.’

Holmes gave me a weak grin. ‘Well, at least we are agreed on that point.’ His eye wandered to the drawer in his bureau where I knew he still kept the neat Morocco case containing the hypodermic syringe.

And that is not the answer either,’ I snapped.