Introduction.

The First Book.

Introduction.

Had

Rabelais never written his strange and marvellous romance, no one

would ever have imagined the possibility of its production. It stands

outside other things—a mixture of mad mirth and gravity, of folly

and reason, of childishness and grandeur, of the commonplace and the

out-of-the-way, of popular verve and polished humanism, of mother-wit

and learning, of baseness and nobility, of personalities and broad

generalization, of the comic and the serious, of the impossible and

the familiar. Throughout the whole there is such a force of life and

thought, such a power of good sense, a kind of assurance so

authoritative, that he takes rank with the greatest; and his peers

are not many. You may like him or not, may attack him or sing his

praises, but you cannot ignore him. He is of those that die hard. Be

as fastidious as you will; make up your mind to recognize only those

who are, without any manner of doubt, beyond and above all others;

however few the names you keep, Rabelais' will always remain.We

may know his work, may know it well, and admire it more every time we

read it. After being amused by it, after having enjoyed it, we may

return again to study it and to enter more fully into its meaning.

Yet there is no possibility of knowing his own life in the same

fashion. In spite of all the efforts, often successful, that have

been made to throw light on it, to bring forward a fresh document, or

some obscure mention in a forgotten book, to add some little fact, to

fix a date more precisely, it remains nevertheless full of

uncertainty and of gaps. Besides, it has been burdened and sullied by

all kinds of wearisome stories and foolish anecdotes, so that really

there is more to weed out than to add.This

injustice, at first wilful, had its rise in the sixteenth century, in

the furious attacks of a monk of Fontevrault, Gabriel de

Puy-Herbault, who seems to have drawn his conclusions concerning the

author from the book, and, more especially, in the regrettable

satirical epitaph of Ronsard, piqued, it is said, that the Guises had

given him only a little pavillon in the Forest of Meudon, whereas the

presbytery was close to the chateau. From that time legend has

fastened on Rabelais, has completely travestied him, till, bit by

bit, it has made of him a buffoon, a veritable clown, a vagrant, a

glutton, and a drunkard.The

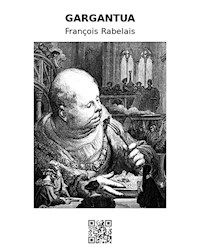

likeness of his person has undergone a similar metamorphosis. He has

been credited with a full moon of a face, the rubicund nose of an

incorrigible toper, and thick coarse lips always apart because always

laughing. The picture would have surprised his friends no less than

himself. There have been portraits painted of Rabelais; I have seen

many such. They are all of the seventeenth century, and the greater

number are conceived in this jovial and popular style.As

a matter of fact there is only one portrait of him that counts, that

has more than the merest chance of being authentic, the one in the

Chronologie collee or coupee. Under this double name is known and

cited a large sheet divided by lines and cross lines into little

squares, containing about a hundred heads of illustrious Frenchmen.

This sheet was stuck on pasteboard for hanging on the wall, and was

cut in little pieces, so that the portraits might be sold separately.

The majority of the portraits are of known persons and can therefore

be verified. Now it can be seen that these have been selected with

care, and taken from the most authentic sources; from statues, busts,

medals, even stained glass, for the persons of most distinction, from

earlier engravings for the others. Moreover, those of which no other

copies exist, and which are therefore the most valuable, have each an

individuality very distinct, in the features, the hair, the beard, as

well as in the costume. Not one of them is like another. There has

been no tampering with them, no forgery. On the contrary, there is in

each a difference, a very marked personality. Leonard Gaultier, who

published this engraving towards the end of the sixteenth century,

reproduced a great many portraits besides from chalk drawings, in the

style of his master, Thomas de Leu. It must have been such drawings

that were the originals of those portraits which he alone has issued,

and which may therefore be as authentic and reliable as the others

whose correctness we are in a position to verify.