Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

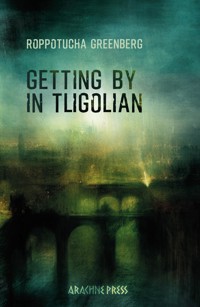

- Herausgeber: Arachne Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

The City-State of Tligol is ruled by dictators, holds monthly public executions and is haunted by a benign, fishing, giant; but by and large the inhabitants are content, and the food is amazing. The perfect place for a city break, just as long as you don't want to leave. Ever. Language has its own relationship to time. When Jennifer falls for Sam at his execution, she doesn't immediately realise that she can still find and live with him; but the city of Tligol has trains that will take her anywhere, including her own past, and future, and multiple possible variations, just as long as she doesn't leave the city. Jennifer rides the trains, loops around in time and sets an unplanned series of events in motion. For lovers of The City and The City... and Hotel California!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 122

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in UK 2023 by Arachne Press Limited100 Grierson Road, London, SE23 1NXwww.arachnepress.com

© Roppotucha Greenberg 2023

ISBNsPrint: 978-1-913665-93-7 eBook: 978-1-913665-94-4

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior written consent in any form or binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Except for short passages for review purposes no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of Arachne Press.

Cover design © Kevin Threlfall 2023

Thanks to Muireann Grealy for her proofreading.

Getting By In Tligolian

In memory,

Lucia (Felicia) Greenberg.

Contents

Lesson 1: The City of Tligol

Study Note 1: Past, Present, and Future

Lesson 2: How to Introduce Yourself to Strange People

Study Note: How I Feel About Sam Now

How I Felt Then

Lesson 3: I am, you are, the cupola, the verb to be

Vocabulary in Focus: Going Out and Having Fun

Study Note (History): Time-travelling Trains

Exercise: Write a Summary of Your Relationship

Culture Note: Explanation of the Existence of the Giant in Tligol

The Verb Ber

Lesson 4: How to Drink Lattes (Transport, Offices, Prisons)

The Canal Beside the Museum

Inspectors are Coming

The Citizens Speak

Regarding the Giant

On History

Study Skills

Tligolian Literature: Lady Emily F and Mr Jones

Lesson 5: Politeness and Fitting In

More Info on the Giant

Free Writing: Meat Pies, Bridges, and Kitchens

Exercise 2: Write Another Way to Explain What Happened in the End

Bad Language

Lesson 6: Saying Goodbye

Vocabulary: Directions, Religion, Footwear

Lesson 7: Making Friends

Back Then

The Evil Forest

Lesson 8: Family Life

The House by the Canal Beside the Museum

You Know

Conversation Practice (With Your Partner)

Lesson 8: Being Good

Exercise: My Winter Coat

Lesson 9: Being Bad

Ice Cream

Sorting Things Out

Fun Fact: Exit Colin

Martha’s Advice

Sam and Me

Lesson 10: Dying, Tligolian-style

What I Am Angry With

Test Your Vocabulary: Talking to a Friend

Odds and Ends

Appendix

Libraries

Grammar

Trains

Lesson 1: The City of Tligol

Soon after I’d turned twenty-one, I found myself in a city where they sold delicate almond pastries at public executions and ignored the time-warping trains. I didn’t like that, but I liked the city and didn’t want to leave, and I’d just got a nifty job in a hotel. I waited on tables, washed huge pots, and, when the Boss exploded and raged, scrubbed everything in sight.

I met Sam at the execution. When Martha told me we were going, all I could think of was that my luck was turning, that there were a few of us and we were going somewhere. And then I was jealous of her friends and angry at how Martha always spoke faster when she was around them. And then it was him being led to the block.

Sam was being led to the block, and I didn’t know his name was Sam. I barely knew it was an execution. We were at the central square, below the glass dome, and the giant columns were lit up by the sun. The Leaders’ portraits flapped in the air. The priest started a quiet chant, and the Tligolian words danced among the crowd. Then the giant puppets were brought, and I was happy for having been there. Then the bell. ‘Only one,’ Martha said. ‘There were three last time.’ The sound of the bell lasted for as long as he walked and contained the whole place, the golden columns, the waving banners, the Leaders’ faces. The prisoner knelt beside the block to say his prayers. Then he looked up, and it was like all of me, the whole of me – the fear and pain of being me rushing at me, drowning me – and then the drums.

I tasted vomit. I heard the start of a group prayer. The light flipped. Martha’s hand was on my shoulder. Water. The water was alive. My hands were like live beasts.

‘Snap out of it.’ Martha was saying something. We had to go. ‘Jenny, get up.’ We were pushed out of the square into the party area on the green. The glass dome opened to let the birds in. ‘The first time is always bad. Eat something.’

Almond pastries were served at the stall, and I studied the stripes on the candy canes, and strangers’ shoes. My thoughts flung open and raced, and in a few seconds, it seemed, I would work it all out. I needed to do something with time. It would be as simple as going out of that domed square and coming back again. It would require as much effort as conjugating irregular Tligolian verbs. I was in shock, of course, but I was also in love (though it took me a while to figure it out), and I was also right – about time that is, and how easy it was to handle in that place.

Study Note 1: Past, Present, and Future

Just before I wake up I hear voices: ‘Jenny, you hear me, get up and leave. Get out of this city, d’you hear me? Get off your butt and go.’ This is older me, talking down to me, and I’d do as she says, but there’s another voice: ‘You know it’s going to be all right, all your choices will work out in the end – except there is no end – and you will be grateful.’

And there are more: slivers of me from different futures, who can’t hear each other, but all have advice to dish out. They are not real reflections, just my sleepy mind tuning into the static and playing tricks with me. Reflections don’t warn you before they appear, and they’re past things.

I’m good at lying in bed in the mornings. The window is above my bed, and the outer wall is thin. All of the outside is also in my room, the cars, and the trams, and the trains, but they don’t know of me. If I could put my hand through the wall and bring it back in, I’d have the solution to everything.

Lesson 2: How to Introduce Yourself to Strange People

My life was different before I met Sam. I’d moved to Tligol in a hurry and settled in the hotel because of a mix up with the phone booking. What with nobody to talk to and the city being so beautiful, I convinced myself that I was in charge of the perfect expression of its beauty. I walked into bakeries to eat local food; I bumped into its secret parks that expanded and turned into forests; and I pretended I was a student.

I bought a sketchbook and some pens in the campus shop and doodled so that I would have something to do. I tried to draw from angles that allowed me to sit in a café and drink something inexpensive while smelling the pastries. I tried to draw the bridge; I tried to draw the town hall. When I caught a glimpse of the giant at the river, I tried to replicate what I saw. It did not quite work. And it was not just because back in the other place I studied the History of Art, instead of drawing or painting, or all those other things I’d wanted to do. I found out that what I actually wanted was to draw combination images. The roofs rushed into the air, but they were bound to the earth. The chimneys were tied to the kegs outside the café, the people talking, and the dark canals. It didn’t work. What I hoped to create on lined paper with a Bic biro was a new masterpiece – a perfect portrait of the Jenny-sky, the sky as I alone discovered it.

All these people around me – I drew myself on the table shouting: ‘People, drop your spoons. Stop sipping your onion soup, oh young man who thinks I am invisible. Get your arm off that girl’s knee, the girl with the clutch bag and pointy shoes. I used to think we would all turn out like that when we grew up, but I was wrong. People of Tligol, listen to me, I’ve been quiet for so long. I am bursting with words. I am sweating conversation.’

After a week of that I thought: there must be a way. I stood next to the bar just as this man was asking for a beer, and stared at him. I was single, after all. Maybe I could be like one of those people who meet other people. I tried talking to him, but then he started talking to the barman, then I sort of turned around, and there was his friend, and I realised, to my horror, that I had somehow wedged myself right in the middle of their conversation. I tried to move out, but next thing the barman came over and barked at me, saying what did I want? And I wanted to die, and said something about a small beer, and then the two men just upped and left, and the barman brought out my beer and a bill for their drinks.

That’s when Tom appeared, shouted at the barman in Tligolian, and sort of ushered me to a little table beside the window.

‘You got to be careful with them, kid,’ he said. ‘They are all crooks. What’s a girl like you doing in this dive anyway?’

I don’t think I could think of the right thing to say, so I ended up just pointing at my sketchbook. He asked me about the techniques I was using, and because I was so conversation starved, I started talking about Cézanne. He told me about that song: This is how you remind me, of what I really am. Back when it came out, he misheard and thought it was Cézanne you remind me... And he thought that was good, because that was exactly how he felt about Cézanne’s apples.

Tom was more of a cartoon character than a person, the way he always found a dartboard in every bar, and the way he talked about the blindness of the masses as soon as he had a few drinks. But then I also thought he was my teacher. Back then I still had a habit of making myself small when talking to people. Tom, I felt, could teach me to stop doing that, or perhaps it was someone else that did it, but I am sure I started curing myself of smallness at that time.

We talked about the city most of all.

‘It is different,’ Tom said. ‘Where you’re from, Jenny, you could leave. This place, that’s a different story.’

I said we were sitting across from the train station, and there were trains going to all those places like Krakow, and London, and St Petersburg.

‘Well why don’t you go on a trip to one of those places?’ he said.

‘Can’t afford to. And I am fine where I am.’

‘You could not do it anyway,’ he said. ‘You could not do it.’

He’d drunk a fair bit already that day and his voice had gone sentimental. He tried to snap out of it, but every new attack of emotion made him drink more, and that in turn made him even more sentimental.

‘You cannot just leave,’ he moaned. ‘You have to curse it first, and you have to mean it, and even then you might not be able to leave.’

Aside from Tom, nobody spoke about the trains. It was impolite. Nobody took them, they claimed. None of my fellow passengers took them. None of them stared out of the window as the static took over and blanked out the world outside. None of them cared that they never arrived at their advertised destinations. Paris, Hamburg, Warsaw – whoever designed those noticeboards had a strange sense of humour – the trains never made it out of the city. And before the execution I never bothered with them.

Study Note: How I Feel About Sam Now

‘You do love him, yeah?’

That’s too blunt, even for Martha. Probably payback for something I did. She is cooking something on the stove, stirring it, and the steam is taking many beautiful shapes. Or maybe she hasn’t asked this at all, but I just zoned out, and then there is no need to answer.

‘It’s like looking at someone from a great distance. It’s like they are so far, there’s no point looking anymore.’

How I Felt Then

It was several weeks later that I gave Martha a few hints about how I felt about that boy who got killed. It was in the kitchen at night and over a bottle, so it was completely all right to ask.

‘He probably did something horrible,’ she said, ‘something really horrible – they don’t do it otherwise – he might have killed someone.’

Martha said she couldn’t explain all the ins and outs (she was not into politics) but that I didn’t need to worry. Executions happened. They took place at regular intervals, and everyone was welcome. Some people attended every single one.

‘Look,’ she said. ‘It happens to everyone – it’s not just you. I suppose the rest of us are kind of used to it, that’s all. It was only your first.’ She was nice and she was kind, and she was also taking advantage of my ignorance. ‘You know, it is good to go to them now and again,’ she said. ‘They remind you of who you are. It’s a bit of a pain, but it’s good in the end.’

We drank to that. She felt sorry for me and told me that there was a way to sneak into the after-party without seeing the gory bit. I told her that was not the point.

‘You are not seriously falling for an execution guy, are you? she said. ‘Everyone goes through that phase, you know, at school, you can’t be taking it too seriously now.’