Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

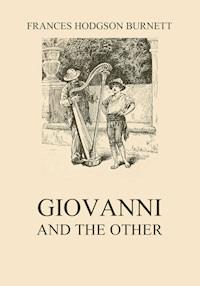

A little Italian boy with a beautiful voice, who comforted Mrs. Burnett when she mourned for her son at San Remo, is the hero of the first story. It is slightly autobiographical, introducing the writer and her tender reminiscences of her lost boy. "The boy who became a Socialist" is a pleasant sketch of " Geof,' her second son. The other stories deal with children she has met all over the world-princes and peasants-and are full of a delightful humor.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 267

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Giovanni and the Other

Children who have made Stories

FRANCES HODGSON BURNETT

Giovanni, F. Hodgson Burnett

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Deutschland

ISBN: 9783849649159

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

CONTENTS:

GIOVANNI AND THE OTHER.. 1

"ILLUSTRISSIMO SIGNOR BÉBÉ". 32

THE DAUGHTER OF THE CUSTODIAN... 40

A PRETTY ROMAN BEGGAR.. 47

EIGHT LITTLE PRINCES. 53

ONE WHO LIVED LONG, LONG AGO... 60

THE LITTLE FAUN... 69

"WHAT USE IS A POET?". 76

THE BOY WHO BECAME A SOCIALIST.. 82

BIRDIE.. 87

THE TINKER'S TOM... 93

THE QUITE TRUE STORY OF AN OLD HAWTHORN TREE.. 103

GIOVANNI AND THE OTHER

I.

Giovanni walked up the enclosed road leading to the great white hotel with the many marble balconies. It was quite a grand hotel and stood in a garden where palm-trees and orange-trees and flowers grew. A white balustraded terrace separated the garden from the carriage drive by the grey-green olives, and roses and heliotropes grew in tumbling masses over the stone. It was on an elevation, and below it one could see the promenade by the sea and the great lake-like sapphire blue expanse of the Mediterranean.

There were palm-trees and flowers bordering the promenade, and even in the winter there were numbers of children walking about with baskets full of violets and narcissus and anemones, which they ran after the pedestrians with, in the hope of selling.

The sun seemed always shining and the air soft there, and there were always flowers, for the little town was a pretty quaint one on the Riviera. It was called San Remo, and in the winter was always full of foreigners who came to see the sun when it seemed finally to have left England, or to escape from wind and cold when they were delicate.

Most of them — the forestieri — were more or less delicate. Some of them had thin, pale faces, and coughed and walked slowly, some of them were pulled about in invalid rolling chairs, and often one saw one in deep mourning, and might guess either that someone belonging to them had come to the south to get well and had died in the midst of the flowers and palms and orange-trees, or that having lost someone they loved in some other place, had come to try to bear the shock of their grief in the land where the sunshine might help them a little.

But whatever had happened to bring them, whether they were well or ill, or burdened with sorrow, they always were pleased with two things. They always were pleased with the flowers and carried them about in bunches, and if any one played the guitar and mandolin and sang well they were pleased, and gave money to the players and singers.

So there were many flower sellers in the streets and many flower shops in the town, and there were many people who wandered about with mandolins and guitars, playing before the hotels, and generally having with them someone who either could sing sweetly or who tried to. In the latter case sometimes they got money to induce them to go away — to the next hotel, at least.

Giovanni was one of those who fortunately could sing, and a man went with him who played the harp.

He was a handsome Italian boy about fourteen years old. He was strong and plump and well-built, and had a dark-eyed, merry, pretty face, and a gay, bright smile. It was rather a lovable face, and when money was thrown to him from the balconies, and he ran and picked it up, pulling off his cap and saying, " Grazie, Signora," or "Signorina," or " Signore," as the case might be, his quick little bow was often returned by a nod.

They had so much money, these forestieri, Giovanni thought they might well be good-natured. Think what lives they must have, these people who were rich enough to travel away from unpleasant weather, and who lived in the great gay hotels, eating wonderful things three times a day, waited upon by dozens of servants, and with an imposing concierge in uniform and gold buttons, who appeared on the broad, white marble, flower-bordered entrance steps, and, calling up a waiting carriage with a majestic wave of the hand and a loud " Avante," carried out to it wraps and cushions, and held the door open while the signoras entered, touching his gold-banded cap gracefully as they drove away. Ah! what a life it must be, to be sure.

But though he was only a little peasant, Giovanni knew that fortune had not been so unkind to him after all. He had his voice, and had had luck with it ever since the man with the harp had proposed that he should go and sing with him before the hotels and villas. Giovanni had a share of the money, and he was comfortably fed and given warm clothes, even to the extent of having a scarf to wrap round his throat on chilly nights, for fear he should catch cold and become hoarse. The man with the harp knew he was worth somethings

He had a full, sweet, strong voice, and he sang his songs of the people with a melodious freshness. He had a little repertoire of his own, and was not reduced to singing "Santa Lucia" as often as many of the street troubadours. There was a little song of a reproachful lover who rather embarrassingly recalls the past to his unkind fair one. "When I am far away," he says, ''you will remember the kisses you have given me. Yes, you will remember then," etc.

And Giovanni used to stand with his hands on his hips and pour forth these reproaches in his clear, full, boyish voice, looking so happy and young and content that it was very charming. And then there was " O je Carolie," and the Ritirata, and the gayest one of all — a rattling little one — about the Bersaglieri — the dashing sharpshooters who went "double quick" through life in their picturesque cloaks and broad-brimmed hats on one side, with the great plumes of cock's feathers sweeping their shoulders.

"The Bersaglieri have feathers on their hats," he sang in Neapolitan dialect. " How many little capons and hens have to be destroyed to provide all this beauty. Love the Bersaglieri — love them — they are the saviours of your country." And all so gaily and with such a swing to the air that one could imagine a Bersagliere hearing him would rush forward and shower upon him unlimited soldi.

The morning my story begins with was a perfect one. It was in January, but San Remo was flooded with brilliant sunshine, the Mediterranean was like a great sapphire, the air was as soft as if it had been May. Giovanni was in a joyous humor — but then he usually was — as he and the man with the harp mounted the long flight of stone steps which led into the hotel garden.

" I wonder how much we shall get," he said to his companion. "The Grand Hotel des Anglais has not been so full this month." That was the name of the hotel they were going to sing and play before.

The man with the harp planted it in a good position before the long flight of broad white marble entrance steps. There were big pots of palms and azaleas and flowering plants of various sorts on each side of the steps all the way up to the glass door which one of the servants always stood behind, ready to open.

Giovanni took his usual boyish pose with his hands on his hips and began to sing. He sang the song of the reproachful lover and the Bella Sorrentina, and in the middle of the last he heard a window open. This was a sound always to be noted, because it meant that someone was coming out on to the balcony to listen and would probably throw him some money. But he was artist enough not to look up until his song was finished. Even if money was thrown he did not move until his song was over. Then he used to run and pick it up, lifting his cap in recognition.

When he had finished La bella Sorrentina he glanced over the front of the hotel. There were several balconies which belonged to the larger apartments, to the people who had suites of two or three rooms and private salons. At the end of one of these a lady was standing leaning against the marble balustrade and resting her forehead on her hand as she looked down at him.

Giovanni saw that she was one of the forestieri who were in deep mourning. She was all black but that she had blonde hair which the morning sun was shining on. There was something sad and fatigued about her attitude, and as he looked up she touched her eyes lightly with the finger of the hand that shaded them; with the other hand she made a motion to Giovanni. She held a tiny white package in it. It was some money folded in a piece of paper so that it could be easily seen and found where she threw it.

Giovanni went and stood under her balcony. She smiled down at him and threw the bit of paper with a sort of friendly, almost caressing, gesture which made him feel that she had liked his voice very much, and which caused him to lilt his cap with spirit and call out with more than usual feeling his " Grazie, Signora."

Then he ran back to the harp — put the white paper into the harpist's pocket, without looking at it or opening it at all — which was really quite dignified artistic taste for a boy street singer — and he began the song about the Bersaglieri. The lady in black rested against the marble balustrade again and shaded her eyes with her hand.

As she did so a tall girl came out upon the balcony and stood close to her. She was a girl with a lovely rounded face and black-lashed grey eyes.

"What a beautiful voice!" she exclaimed enthusiastically. "What a darling, full, sweet boy voice! What a good voice! And how well he sings."

"He has a dear boy face, too," said the other. "He looks so bright and happy. He looks about as old as Geof, I think. He has just sung one of Geof's songs, ' La bella Sorrentina; ' you know he sings that."

The girl gave her a soft, quick, side glance, and drew closer to her, touching her caressingly.

" Don't, dear," she said; "you must not have tears in your eyes."

"Well," answered the lady in black, quietly, and looking over the olives at the sea, " it is so strange how every moment something reminds me. Everything makes me remember something — the palm trees and oranges and flowers that we hoped he would be strong enough to be brought to see — the Mediterranean that he used to plan to use his launch on — ah! everything has some connection of thought with him — and when that boy began, it brought back the days when Geof used to stand singing with his hands on his hips — and how he used to sit near and listen and think it was so clever. He used to say, ' Oh, Geof can sing. He's got a voice — but I couldn't do it. I never saw such a fellow as Geof; he can do anything.' You know he always admired Geof's gifts, in a boyish way. And I could not help thinking that if — if all the stories are quite true, the stories of the Far Country where he has gone — perhaps now he sings, too."

She drew her palm softly and quickly across her cheek.

"It makes me feel as if I loved that little fellow down there," she said. " Boys always seem near to me, you know. There, he has finished singing and they are going."

That was the beginning of Giovanni's acquaintance with the lady in black.

II.

He used to come back to sing before the hotel twice a week, and always after the first few bars of his song she used to appear on the balcony and lean on the marble and listen, and watch him. He was always sure of having his silver franc thrown down, folded in paper. On the morning of the Flower Corso, at the end of the Carnival, she threw him two, and often the girl with the grey eyes threw him one also. They never threw him coppers, and they generally waved their hands to him and said, "Buon giorno," as he picked up his money.

Whether money was thrown from other balconies or not he was always sure of his little revenue from the one where the black figure stood listening-.

Being a bright, spirited boy who liked to be appreciated, he began to rather look forward to his mornings before the hotel. He felt somehow as if these ladies liked him and were his friends. He began even to feel that he had a sort of claim upon them, and he always sang his best under their balcony and made his most graceful bow.

One day they were walking through the town and a boy passing them stepped aside from the narrow pavement, and pulling off his cap said brightly, —

" Buon giorno, Signore."

The tall girl turned to look at him.

"Ah," she said, "that is our boy who sings. He is alone and he knew us and said ' Buon giorno.' "

The lady in black turned also. " Yes, it is our boy," she said. "Ah, let us go back and talk to him a little. I want to see him closer."

To Giovanni's surprise they turned back and came towards him. He stopped and pulled off his cap again. He had a smooth, pretty dark-haired head, and seen close to he was a handsome boy with a merry smiling face.

"You sing for us before our hotel, don't you? " said the grey-eyed girl, speaking Italian.

" Si, Signorina," he answered, feeling pleased at her gentle, friendly manner.

" What is your name? "

" Giovanni Calcagni."

" And you are fond of music? "

" Si, si, Signorina," smiling.

Then they asked him how old he was and where he had learned to sing, and he told them he was fourteen and had always sung little songs; but about three years ago a one-eyed man had taken him about with him to sing before the villas and hotels, and so he had learned to sing better.

" The Signora here," said the tall girl, "has a boy who is fourteen years old, like you, and he has a beautiful voice and sings some of our Italian songs, so the Signora likes to hear you sing, very much."

"Is the Sienorino in San Remo? " Giovanni asked.

" No, he is not in San Remo. He is in America."

Giovanni had heard of America. It was far away. A long voyage across the sea. People went there and became rich. There had been a San Remese sailor, quite a common man, who had gone there, and after two years had come back and built a wonderful villa by the sea. It was a marvelously ornamented villa, fantastically decorated. Giovanni had once heard that there were forestieri who smiled at it and said it was decorated like a wedding cake. But it was known to have cost a great deal of money, and the owner had made all this money in America, though no one knew how. Probably he had picked it up in the streets.

This made the lady in black and her friend additionally interesting. They were of course rich, as they lived at the Grand Hotel des Anglais and threw out silver to singers. But it was more than interesting to hear of a boy of his own age who lived in America and also sang "La bella Sorrentina," and the rest, in Italian. It seemed enviable.

The lady in black looked at him with longing in her eyes, and she gave him a franc for himself on the spot, and then the two smiled and left him.

" I wonder," said the lady in black, as they walked along the promenade under the palm trees, " I wonder if he will have a fine voice when he is a man. It is difficult to tell, I suppose; I have always heard so. Musicians always advise me not to let Geof use his voice too much now he is crowing" older."

" That is the great point, I believe," said her companion. " Giovanni's voice is a beautiful one, but it may not be so fine when it changes into a man's voice — certainly it won't if he strains it by singing too much now and by forcing his notes."

" It would be a cruel thing for it to be spoiled," returned the lady in black, reflectively. " Think what a future it might make for him if, when he is a young man, he had that splendid gift."

" Now you are making a story out of him," said the girl, with a caressing little laugh. " You are imagining he may have a career before him and be a world-renowned tenor. I know your little ways."

The lady in black smiled.

"Yes," she answered, "of course. I am a romantic person, and I will have my story whenever there is a shadow of a chance. See what a story it would be, Gertrude. Here he is — Giovanni, a perfectly simple, ordinary little peasant boy, singing about the streets with a one-eyed man and a harpist, and feeling quite rich when one throws him a franc. I have no doubt he thinks it is quite splendid to be one of the forestieri and live in a hotel. He probably lives in one of the queer old, old tumbling-down houses in the ' Citta Vecchia' — one of those in the climbing streets which are like corridors, and have little archways thrown from house to house, and apparently no windows, only tiny square holes, with rusty bars across. You remember how dark they are, and how green things grow out of the stones, and how sometimes there are sheep or cows in the room on the first floor.

"We will suppose he lives there, and sits with the sheep when it is cold. He eats polenta and farinata and castagnone — those brownish and yellowish slabs which look like uninviting pudding when one sees them being cooked over the charcoal fires in the narrow streets. They are made of maize or chestnut flour, and it does not give one an appetite to look at them. Sometimes he has maccaroni and goat cheese, and in the summer he eats ripe figs and grapes and black bread. Perhaps he never had a franc all to himself until I gave him that one to-day. I wonder what he will do with it? Perhaps he will buy that hard, sticky cake made of nuts. He looks like a dear boy, but I don't think he looks imaginative or ambitious. I don't imagine he dreams about a career. Now, imagine that this beautiful boy's voice changes into a wonderful tenor. Imagine that someone helps him to cultivate it, and brings him before the world, and it begins to applaud and adore him."

" It would be like a fairy story," said Gertrude; " he would think he was living in a dream.''

" He would be rich,'' said the lady in black. " He would travel from country to country, and everywhere he would be feted and caressed. Of course we are imagining him to be a sort of king of tenors, and not one with an ordinarily good voice. Kings and queens would hear him and praise him, and if he were a charming fellow would make a sort of favorite of him. I think he would be a charming fellow, don't you? He has a bright, handsome face."

The girl with the grey eyes turned to look down at her friend — (she was the taller of the two) — -with her soft, caressing, little laugh.

"I think he would," she said; "we will imagine he would be perfectly beautiful and perfectly delightful as we are imagining things. It makes the story prettier."

"That is the advantage of imagining:" said her friend. " One can make the story as pretty as one likes. I wonder if he has a mother in the Citta Vecchia, and if he would remember her and her love when he was a great tenor? Let us imagine that he would — and imagine how proud and radiantly happy she would be. Poor little peasant woman, I hope the grandeur and the kings and queens would not frighten her."

" Think how she would feel sitting in a box at the opera — at La Scala, for instance," said the girl. " She would have had to lay aside her short petticoats and her peasant bodice, and have learned to wear a bonnet instead of a red and yellow and green handkerchief tied over her head."

"And she would have very large grand ear-rings, I am sure," went on the lady in black, with a little softly-smiling reflective air. " Giovanni would have given them to her for a present. Don't you think she would choose some of those big" ancient ones we see in the curiosity shops, with queer stones in them and a great deal of turquoise? They say those have all been bought from peasants. I think she would be sure to want a pair. Diamonds would seem quite cold and plain to her, dear simple old thing. She would want turquoise and garnets and amethysts and yellow old pearls set elaborately in silver gilt."

" How real she seems," smiled the girl with the grey eyes; and then they looked at each other, and her friend smiled also.

" Well," she said, "he has a voice — and he might have a career — and it is more than probable that he has a mother — so it is easy to imagine a story for him. I wish we could do something to help to make it real. Why should he eat polenta and live like a peasant always if he has a gift? I am going to think about him, and see if — well, if there is anything to be done."

"You always want to make your stories come true, don't you?" said her companion.

The lady in black looked out far over the sunlight sapphire sea. She seemed to be thinking of something that stirred in her a sad tenderness.

" I might make him one of Leo's friends," she said, " one of those boys he helps."

"You are always thinking of Leo, I think," the girl said very gently. " He seems very near to you, dear."

" Very near," was the answer. "I could not let him seem far away. He is more real than anything else. Sometimes I think he seems even more real than Geof, who is alive and strong and happy, and always busy. A year ago Leo was alive and like him. He was so strong and bright, and so full of the things he was interested in. I can't let him go just because of that morning when his brown eyes closed so softly and his arms unclasped themselves and slipped slowly away from my neck. I must comfort myself in some way — so I try to imagine things about him too — and I try to make them seem quite real."

The girl with the grey eyes put her hand through her arm and drew it to her side with a tender pressure.

" Dear! " she said.

Two large quiet drops slipped down her friend's cheeks, but no others followed them, and she went on speaking, with even a little smile on her lips.

" I say to myself that he has gone to a Fair Far Country," she said. " Perhaps it is because I am a very earthly person that I have to make it so real to myself. I tell myself that other mothers' sons go away to far countries to live. You know there are so many who go to foreign lands to make their fortunes. But their mothers do not feel as if they had lost them. And I know they must comfort themselves by doing things for them and reading books about the countries they have gone to. If Leo had gone to Africa, think how I should have read about Africa. As it is, I read over and over the parts of those last chapters which tell about the City, the City that has streets of pure gold, like unto clear glass. It always seemed like a beautiful fairy story, until Leo went away. And then I was so hungry for him — it seemed as if I must have something real to think of, so I began to read, and imagine. I wish there was more to read. I like to remember that ' the gates of it shall not be shut at all by day — and there is no night there.' He was so happy when he was on earth, I can't help trying to make it a place that would not seem too dazzling and strange and solemn for a boy to like. He was only such a boy, you know, and at first I could not help feeling timid and hoping that it would not overwhelm and bewilder him. I try to remember more about the green pastures and the river of crystal than about the walls of jasper and sapphire, and emerald, and the streets of gold. But somehow I love the gates made of great pearls, and always standing open."

" You do make it real, don't you, dear?" said the girl.

" I must make it real, I must do things to comfort myself and make me feel that I am not letting him go. That is why I have my fancy about helping those other boys whom I call his friends. If he had lived to be a man he might have had sorrow and pain and disappointment — he might have known temptation and have fallen into human fault. That is all over for him — he can never be touched now. Why should not I go on with the sweet kind things he might have done? You know there would have been many of them. He had a tender, generous heart — and in the life of a man with a heart like that there must be many good things done for others, even if there should be human weakness and sorrow too. I don't want the sweet things to go undone just because he has died. That would be as if those he might have helped had been robbed of a friend. When he was a baby I used to say, ' I want the big world to be better just because he lives.' Now I say, ' I want it to be better even that he has lived — and died.' "

"And that is why you are so interested in Giovanni? I knew it was like that, dear," with another soft pressure of the arm.

" In Giovanni — in any boy whose life might be made brighter and broader — in any boy who needs help or a friend. It might not always be money that would help them most. It might be something else. Whatever is done, it is not I who do it — it is Leo. Leo, who will never be tempted or made sad by life, but who goes on living and holding out his kind, boyish, friendly young hand to other boys who must finish their lives and bear all the burdens of them. He was spared them all. He lived a few bright, buoyant, joyous years without a shadow or a stain. Now he seems to me like a magnificent, fair young prince in his royal city, with his hands full of royal gifts, and his soul full of tender yearning for those who are outside the gates and who must toil longer in the heat of the sun."

"And he will help Giovanni?" said her friend. "I see that."

" He will try," was the answer.

III.

The little salon out of which one stepped on to the white marble balcony was a very pretty one. It had not been particularly pretty when the lady in black and her friend first took possession of it. Then it had worn the usual ungarnished air of nearly all hotel rooms. Now it was quite bright and gay. The curiosity shops had been levied upon for antique brocades, for rich tenderly-faded old vestments whose colors of a hundred or two years ago had melted into wondrous shades, and which were draped on the walls, and thrown over pieces of furniture. There were many cushions covered with squares of such brocade, there were draperies over the doors, there were Spanish fans and odd trifles here and there, there were studies of peasants and the Citta Vecchia, and branches of orange trees, and olives, and eucalyptus blossom, there were bits of Louis Quatorze silver and china, and painted and gilded fans on the mantel; there were bowls and vases of jonquils and mimosa, and narcissi and violets everywhere — there were many violets, the air was full of their breath, and wheresoever one's eye turned it rested on the pictured face of a boy, who watched one with shadowy velvet dark eyes. There were several pictures of him, and each one had before it a cluster of violets.

" He had always been used to seeing me wear violets," his mother said. " When he was a little fellow he used to bring me all he could find in the garden. And the first time he was in London he saw some crystallized bunches in a confectioner's in Regent Street, and he spent all his pennies to buy me some, and brought them to me for a present, with such an innocent pride. When he was ill and people sent him flowers, he used to say to his nurse: ' Give all the violets to mammie. All the violets are for her.' When he went to sleep that last day I covered him with them. In the medallion with his miniature, which I always wear, there is one shut inside with him. They mean so much more to me now."

When they were not walking or driving together she and the girl with the grey eyes used to sit in this little salon among the flowers and soft colors and talk of their problems and dreams and imaginings. They had a great many. Theirs was a very dear friendship. They loved and understood each other very tenderly and completely. They had the same emotions, the same fancies. There was never any danger that one could be too imaginative or subtle for the other. They had the same tastes and sympathies and the shades in which they varied only gave interest to their thoughts and words.

The evening after they had met Giovanni was mild and warm, and the windows on the balcony were open. The lady in black lay upon a sofa with many cushions.

In the midst of their quiet talk the strings of a guitar were touched in the garden below. It was rather a good guitar, and the opening bars of a song were being played.

" Someone is going to sing," said the lady in black; " but it is not Giovanni. He is always with the harpist."

And then they heard the singer begin his song.

" It is far from being Giovanni's voice," exclaimed Gertrude. " Poor thing, how bad it is."

Her friend raised her head to listen.

"And it is a boy's voice, too," she said; "but it sounds all strained and cracked. Ah, how pitiful. He ought not to sing at all."

" It is strained," said Gertrude. " Poor boy, it has been a good voice once — perhaps as good as Giovanni's. But he has been singing too much, and has forced it until it is broken. What a cruel pity! "

It was a piteous enough thing to hear — the poor voice rising from among the palms and roses below. It was so roughened, so strained and broken.

" It makes me sad," said the mother. " It sounds so mournful rising out of the dark. Giovanni comes and sings in the morning when all the world is full of sunshine, and he seems like a happy young bird. This poor boy stands alone there in the darkness as if he knew his helplessness and did not care to be seen. I wonder if Giovanni knows him; if he knows Giovanni, and if it is not a bitter thing for him. Let us go and look down at lm.

They went out on to the balcony and looked down, but they could not really see the singer. They could only imagine they saw a shadow which might after all be part of the shade behind some orange trees; but the poor hoarse voice struggled through the song to the end.

" No one opens the windows to throw him money," said the lady in black. "They don't want to hear him. I do not want to hear him — it is too sad; but I shall throw him money. He needs it more than Giovanni. Everybody gives him something — everyone wants him. No one wants the poor other one."