5,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Edizioni Aurora Boreale

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

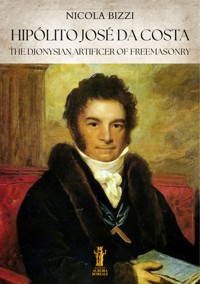

Hipólito José da Costa (13 August 1774 - 11 September 1823) was a great Brazilian writer, journalist, diplomat and freemason, universally considered to be the “father of Brazilian press”.

Persecuted and imprisoned by the Portuguese Inquisition for his Masonic affiliation, Da Costa took refuge in London, where he made a great contribution to the growth and development of Freemasonry. Da Costa played a leading role in persuading the British government to recognize the independence of Brazil in 1823 and indicated the place where Brasilia, the present Capital of Brazil, would be built.

All the great mystery and initiatory traditions of Mediterranean antiquity, from Egypt to Greece, from Italy to the Near East, had their own secret brotherhoods of builders under their control. Secret brotherhoods that held the secrets of geometry and sacred geography, which with their silent work have achieved over the centuries the mirroring of heaven on earth, building the largest and most majestic temples of human spirituality. The fundamental work by Da Costa entitled

The History of the Dionysian Artificers, published in London in 1820, a real milestone in the history of Masonic literature, a precious book that all Masons should read and jealously keep in their library, provides us with important keys to reading and understanding this fascinating and mysterious context.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

SYMBOLS & MYTHS

NICOLA BIZZI

HIPÓLITO JOSÉ DA COSTA THE DIONYSIAN ARTIFICER OF FREEMASONRY

Edizioni Aurora Boreale

Title: Hipólito José da Costa, the Dionysian Artificer of Freemasonry

Author: Nicola Bizzi

Publishing series: Symbols & Myths

Editing by Nicola Bizzi

ISBN: 979-12-5504-684-4

Edizioni Aurora Boreale

© 2024 Edizioni Aurora Boreale

Via del Fiordaliso 14 - 59100 Prato - Italia

www.auroraboreale-edizioni.com

HIPÓLITO JOSÉ DA COSTA

THE DIONYSIAN ARTIFICER OF FREEMASONRY

Hipólito José da Costa Pereira Furtado de Mendonça was a great Brazilian writer, journalist, diplomat and freemason, universally considered to be the “father of Brazilian press”.

He was born in Colonia del Sacramento, a town on the borderland between the Spanish and the Portuguese colonies in South America, nowadays in the southwestern Uruguay, in August 13 1774, from Félix da Costa Furtado de Mendonça, an officier of the Army, and Ana Josefa Pereira. His brother was José Saturnino da Costa Pereira, who became a senator of the Empire of Brazil and the commander of the Brazilian Army.

Soon after the birth of Hipólito José, in 1777, following the signature of the Treaty of Santo Ildefonso that finally established the new borders, the Da Costa family moved to Pelotas, in Rio Grande do Sul, a state in the southern region of Brazil, where he would spend his adolescence. Hipólito José received his primary schooling in Porto Alegre, where he came under the tutorship of his uncle Pedro Pereira Fernández de Mesquita, who prepared him for the entrance examinations to the university.

According to Leon Zeldis1, on October 29 1792, at the age of 18, he enrolled in the Faculty of Mathematics at the University of Coimbra, Portugal, and a month later he also entered the Faculty of Philosophy. On October 18 of the following year he entered the Faculty of Law, graduating on 5 June 1798, being 24 years old.

In Coimbra, Hipólito José was influenced by the liberal reforms introduced into university studies by the Marquis of Pombal. A year earlier his family was awarded a coat-of-arms by King John VI.

Even in 1798, three months after graduation, Da Costa was sent on a semi-secret (officially “diplomatic”) mission to the United States of America by the Portuguese Minister of the Navy and Commerce, Rodrigo de Souza Coutinho, Count of Linhares, to study in the new Republic various aspects of agriculture and industry that might be of use to the Portuguese kingdom.

Hipólito José sailed to Philadelphia, at that time the Capital of the United States, on October 16 1798, arriving at the City of Brotherly Love on December 13, after 59 days of travel. He remained in the United States for two years. Apart from observing the methods used for the extraction and processing of minerals, the cultivation of various plants, such as tobacco and cotton, the building of wooden bridges, the production of silk and other aspects of the economy, Da Costa wanted to get from Mexico the Cochineal insects and plants, intending to introduce them in Portugal.

A Portrait of Hipólito José Da Costa by an unknown artist

During his journey he moved among the highest circles of American society. He met President Adams and was impressed by his simplicity, so different from the Portuguese stiff court protocol. He also had the opportunity to meet Thomas Jefferson, the Secretary of State Timothy Pickering and Oliver Walcott, who succeeded Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury, and also made contact with French émigrés, who had escaped from the Revolution, the Terror and, later, from Napoleon.

He lived in America for about two years, but did not remain in Philadelphia. He made extensive trips in the United States and Canada and wrote monographs and lengthy reports on all his observations, delivered personally to the Portuguese Minister. As pointed out Leon Zeldis2, some of his reports remained forgotten in dusty archives, and were published only in 1955 by the Brazilian Academy of Letters under the title Diário de Minha Viagem para a Filadélfia (Diary of my Voyage to Philadelphia).

According to many sources, including William Almeida de Carvalho3, Da Costa was initiated to Freemasonry in Philadelphia, in Lodge George Washington No. 59 on March 2 1799, at the age of 25 years. Not long after, he requested a Demit (official release from the lodge), probably contemplating his return to Portugal and fearing – with good reason, at it turns out – the persecution of Masons instigated by the Catholic Church. Unfortunately, the archives of the George Wahington Lodge concerning 1799 were lost in a fire in 1819.

After returning to Portugal in 1800 from his mission in the United States, Hipólito José contacted Portuguese Freemasons, like the Worshipful Master of Lodge Concórdia, José Joaquim Monteiro de Carvalho e Oliveira, who requested his assistance in opposing the persecutions of Pina Manique. At the same time, he was appointed as literary director of the Impreçao Régia (Royal Printers) receiving the authority to decide all what would be published.

On April of 1802, the Portoguese Minister of Navy and Commerce again sent him abroad on a mission, this time to England, in order to purchase machinery for the press and books for the Royal Library. This appears to be the source of his later enthusiasm for journalism.

While in London on official business, Da Costa attended the Premier Grand Lodge on 12 May, 1802. He was received as the plenipotentiary representative of four Portuguese lodges that wanted to receive from the Grand Lodge of England regular authority to practice the rites of the Order under the English banner and protection. This is definite proof that he was a regular Mason at the time, since otherwise the Grand Lodge would have refused all contact with him. Some writers claim that the Portuguese wanted to establish a Grand Lodge of Lusitania to work in amity with the British one, but they provide no supporting evidence for this claim. After deliberation, the Grand Lodge decided to encourage the Portuguese Brethren, who might enroll their names in its records, and conform to the constitutions of the Order, but on condition that a list of their names be sent to England as well as a recommendation from their local government officials before their request could be approved.

Rumors of his Masonic activities in London reached quickly Portugal. Although forewarned that he risked arrest if he returned, Da Costa paid no heed and went back to Lisbon at the end of June. The warnings were justified, as he was promptly accused of spreading Masonic ideas through Europe and arrested by José Anastácio Lopes Cardoso, Court Crimes Corregidor, following the instructions of the infamous Chief of Police Diogo Ignacio de Pina Manique, that was virulent in his hatred of Masonry. In a letter to the Regent, John (who had to take power because of his mother’s madness), he claimed that the Freemasons were declared enemies of all and any religion, but in particular the Christian one, and that in Masonic meetings «an image of crucified Jesus was mocked, manhandled, spit upon and dragged». According to the Brazilian writer José Castellani, he also declared that he had «a thirst that could be slaked only with the blood of Freemasons». Portugal was ruled at the time by Queen Maria I “the Mad” who was a fanatic persecutor of Masons and conducted a veritable witch-hunt against them.