Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

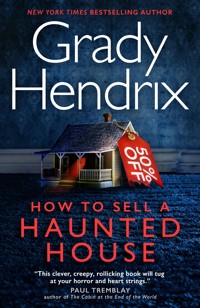

Your past and your family can haunt you like nothing else… A hilarious and terrifying new novel from the New York Times bestselling author of The Final Girl Support Group. When Louise finds out her parents have died, she dreads going home. She doesn't want to leave her daughter with her ex and fly to Charleston. She doesn't want to deal with her family home, stuffed to the rafters with the remnants of her father's academic career and her mother's lifelong obsession with puppets and dolls. She doesn't want to learn how to live without the two people who knew and loved her best in the world. Mostly, she doesn't want to deal with her brother, Mark, who never left their hometown, gets fired from one job after another, and resents her success. But she'll need his help to get the house ready for sale because it'll take more than some new paint on the walls and clearing out a lifetime of memories to get this place on the market. Some houses don't want to be sold, and their home has other plans for both of them… Like his novels The Southern Book Club's Guide to Slaying Vampires and The Final Girl Support Group, How to Sell a Haunted House is classic Hendrix: equal parts heartfelt and terrifying—a gripping new read from "the horror master" (USA Today).

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 598

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

How to Sell A Haunted House

Chapter 1

Denial

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Anger

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Bargaining

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Depression

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Acceptance

Chapter 38

About the Author

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

How to Sell a Haunted House

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781803360539

Waterstones & Forbidden Planet edition ISBN: 9781803365152

Broken Binding edition ISBN: 9781803365169

Export paperback ISBN: 9781803361642

Australian export edition: 9781803365176

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803360546

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: January 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2023 by Grady Hendrix. All Rights Reserved.

The right of Grady Hendrix to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Amanda,You are with me everywhere,I see you where I go,As if you surround me always,Even thoughI knowExactly where I buried you.

HOW TOSELL AHAUNTEDHOUSE

Chapter 1

Louise thought it might not go well, so she told her parents she was pregnant over the phone, from three thousand miles away, in San Francisco. It wasn’t that she had a single doubt about her decision. When those two parallel pink lines had ghosted into view, all her panic dissolved and she heard a clear, certain voice inside her head say:

I’m a mother now.

But even in the twenty-first century it was hard to predict how a pair of Southern parents would react to the news that their thirty-four-year-old unmarried daughter was pregnant. Louise spent all day rehearsing different scripts that would ease them into it, but the minute her mom answered and her dad picked up the kitchen extension, her mind went blank and she blurted out:

“I’m pregnant.”

She braced herself for the barrage of questions.

Are you sure? Does Ian know? Are you going to keep it? Have you thought about moving back to Charleston? Are you certain this is the best thing? Do you have any idea how hard this will be alone? How are you going to manage?

In the long silence, she prepared her answers: Yes, not yet, of course, God no, no but I’m doing it anyway, yes, I’ll manage.

Over the phone she heard someone inhale through what sounded like a mouthful of water and realized her mom was crying.

“Oh, Louise,” her mother said in a thick voice, and Louise prepared herself for the worst. “I’m so happy. You’re going to be the mother I wasn’t.”

Her dad only had one question: her exact street address.

“I don’t want any confusion with the cab driver when we land.”

“Dad,” Louise said, “you don’t have to come right now.”

“Of course we do,” he said. “You’re our Louise.”

She waited for them on the sidewalk, her heart pounding every time a car turned the corner, until finally a dark blue Nissan slowed to a stop in front of her building and her dad helped her mom out of the back seat, and she couldn’t wait—she threw herself into her mom’s arms like she was a little kid again.

They took her crib shopping and stroller shopping and told Louise she was crazy to even consider a cloth diaper service, and discussed feeding techniques and vaccinations and a million decisions Louise would have to make, and bought snot suckers and diapers and onesies, and receiving blankets and changing pads and wipes, and rash cream and burp cloths and rattles and night-lights, and Louise would’ve thought they’d bought way too much if her mother hadn’t said, “You’ve hardly bought anything at all.”

She couldn’t even blame them for having a hard time with the whole Ian issue.

“Married or not, we have to meet his family,” her mom said. “We’re going to be co-grandparents.”

“I haven’t told him yet,” Louise said. “I’m barely eleven weeks.”

“Well, you’re not getting any less pregnant,” her mom pointed out.

“There are tangible financial benefits to marriage,” her dad added. “You’re sure you don’t want to reconsider?”

Louise did not want to reconsider.

Ian could be funny, he was smart, and he made an obscenely high income curating rare vinyl for rich people in the Bay Area who yearned for their childhoods. He’d put together a complete collection of original pressing Beatles LPs for the fourth-largest shareholder at Facebook and found the bootleg of a Grateful Dead concert where a Twitter board member had proposed to his first wife. Louise couldn’t believe how much they paid him for this.

On the other hand, when she suggested they should take a break he’d taken that as his cue to go down on one knee in the atrium of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and propose. He’d been so upset when she said no that she’d finally had pity sex with him, which was how she came to be in her current condition.

When Ian had proposed, he’d been wearing his vintage Nirvana In Utero T-shirt with a hole in the collar that had cost him four hundred dollars. He spent thousands every year on sneakers, which he insisted on calling “kicks.” He checked his phone when she talked about her day, made fun of her when she mixed up the Rolling Stones and The Who, and said, “Are you sure?” whenever she ordered dessert.

“Dad,” Louise said. “Ian’s not ready to be a parent.”

“Who is?” her mom asked.

But Louise knew Ian really wasn’t ready.

Every family visit lasts three days too long, and by the end of the week Louise was counting the hours until she could be alone in her apartment again. The day before her parents’ flight home, she holed up in her bedroom “doing email” while her mom took off her earrings to take a nap and her dad left to find a copy of the Financial Times. If they could do this until lunch, then go on a walk around the Presidio, then dinner, Louise figured everything would be fine.

Louise’s body had other plans. She felt hungry now. She needed hard-boiled eggs now. She had to get up and go to the kitchen now. So she crept into the living room in her socks, trying not to wake her mom because she couldn’t handle another conversation about why she wouldn’t let her hair grow out, or why she should move back to Charleston, or why she should start drawing again.

Her mom lay asleep on the couch, on one side, a yellow blanket pulled up to her waist. The late-morning light brought out her skeleton, the tiny lines around her mouth, her thinning hair, her slack cheeks. For the first time in her life, Louise knew what her mother would look like dead.

“I love you,” her mom said without opening her eyes.

Louise froze.

“I know,” she said after a moment.

“No,” her mom said, “you don’t.”

Louise waited for her to add something, but her mom’s breathing deepened, got regular, and turned into a snore.

Louise continued into the kitchen. Had she overheard half of a dream conversation? Or did her mom mean Louise didn’t know she loved her? Or how much she loved her? Or she wouldn’t understand how much her mom loved her until she had a daughter of her own?

She worried at it while she ate her hard-boiled egg. Was her mom talking about her living in San Francisco? Did she think Louise had moved this far away to put distance between them? Louise had moved here for school, then stayed for work, although when you grew up with all your friends telling you how cool your mom was and even your exes asked about her when you bumped into them, you needed some distance if you wanted to live your own life, and sometimes even three thousand miles didn’t feel like enough to Louise. She wondered if her mom somehow knew.

Then there was her brother. Mark’s name had only come up twice on this visit and Louise knew it ate at her mom that the two of them didn’t have a “natural” relationship, but, to be honest, she didn’t want a relationship with her brother, natural or otherwise. In San Francisco, she could pretend she was an only child.

Louise knew she was a typical oldest sibling, a cookie-cutter first child. She’d read the articles and scanned the listicles, and every single trait applied to her: reliable, structured, responsible, hardworking. She’d even seen it classified as a disorder—Oldest Sibling Syndrome—and that made her wonder what Mark’s disorder was. Terminal Assholism, most likely.

When people asked why she didn’t speak to her brother, Louise told them the story of Christmas 2016, when her mom spent all day cooking but Mark insisted they meet him for dinner at P. F. Chang’s, where he showed up late, drunk, tried to order the entire menu, then passed out at the table.

“Why do you let him act like that?” Louise had asked.

“Try to be more understanding of your brother,” her mom had said.

Louise understood her brother plenty. She won awards. Mark struggled through high school. She got a master’s in design. Mark dropped out of college his freshman year. She built products that people used every day, including part of the user interface for the latest iteration of the iPhone. He was on a mission to get fired from every bar in Charleston. He only lived twenty minutes away from their parents but refused to lift a finger to help out.

No matter what he did, her parents lavished Mark with praise. He rented a new apartment and they acted like he brought down the Berlin Wall. He bought a truck for five hundred dollars and got it running again and he may as well have landed on the moon. When Louise won the Industrial Designers Society of America Graduate Student Merit Award she gave the trophy to her parents to thank them. They put it in the closet.

“Your brother is going to be hurt we have that out for you and nothing for him,” her mom had said.

Louise knew that her not speaking to Mark was the eternal elephant in the room, the invisible ghost at the table, the phantom strain on every interaction with her parents, especially with her mom, who hated what she called “unpleasantness.” Her mom was always “up,” she was always “on,” and while Louise didn’t see anything wrong with being happy, her mom’s enforced happiness seemed pathological. She avoided hard conversations about painful subjects. She had a Christian puppet ministry and acted like she was always onstage. The few times she lost it as a mother she’d snap, “You’re embarrassing me!” as if being embarrassed was the worst possible thing that could happen to someone.

Maybe that’s why she was so certain about her decision to have this baby. Becoming a mother would allow her and her mom to share something just between them. It would bring them closer together. She suspected all the things that annoyed her about her mom were exactly the things that would make her an incredible grandmother.

As Louise brushed eggshell off the counter, she thought that shared motherhood might form a bridge between them, and gradually the walls Louise had needed to protect herself would come down. It wouldn’t happen overnight, but that was okay. They’d have a lifetime to adjust to each other’s new roles—a daughter becoming a mother, a mother becoming a grandmother. They would have years.

As it turned out, she got five.

DENIAL

Chapter 2

The call came as Louise desperately tried to convince her daughter that she was not going to like The Velveteen Rabbit.

“We just got all those new library books,” she said. “Don’t you want—”

“Velverdeen Rabbit,” Poppy insisted.

“It’s scarier than The Muppet Christmas Carol,” Louise told her. “Remember how scary that was when the door knocker turned into the man’s face?”

“I want Velverdeen Rabbit,” Poppy said, her voice firm.

Louise knew she should take the path of least resistance and just read Poppy The Velveteen Rabbit, but that would happen over her dead body. She should have checked the package before letting Poppy open it, because of course her mom hadn’t sent the check for Dinosaur Dig Summer Camp like she’d promised, but she had randomly sent Poppy a copy of The Velveteen Rabbit because she thought it was Louise’s favorite book.

It was not Louise’s favorite book. It was the source of Louise’s childhood nightmares. The first time her mom had read it to her she’d been Poppy’s age and she’d burst into tears when the Rabbit got taken outside to be burned.

“I know,” her mom had said, completely misreading the situation. “It’s my favorite book, too.”

The book’s emotional cruelty made five-year-old Louise’s stomach hurt: the thoughtless Boy who abused his toys, the needy toys who pathologically craved his approval no matter how much he neglected them, the remote and fearsome Nana, the bullying rabbits living in the wild. But her mom kept picking it for her bedtime story, oblivious to the fact that Louise would lie rigid while she read, hands gripping the sheet, staring at the ceiling as her mom did all the voices.

It was a master class in acting, a star turn by Nancy Joyner, and getting to deliver this performance was the real reason her mom kept picking the book. By the end, they’d both be crying, but for very different reasons.

“Does it hurt?” asked the Rabbit.

“Sometimes,” said the Skin Horse. “When you are Real, you don’t mind being hurt.”

Louise had dated a girl at Berkeley who had that exact quote tattooed on her forearm and she wasn’t surprised when she found out that she gave herself tattoos with a sewing needle taped to a BIC pen.

The Velveteen Rabbit confused masochism with love, it wallowed in loneliness, and what kind of awful thing was a Skin Horse, anyway?

Louise wouldn’t make the same mistake with Poppy. There would be no Velveteen Rabbit in this house, even if she had to fight dirty.

“You’re going to hurt the feelings of all those new library books,” Louise said, and instantly Poppy’s eyes got wide. “They’re going to be sad you didn’t want to read them first. You’re going to make them cry.”

Lying to Poppy felt awful, pretending inanimate objects had feelings felt manipulative, but every time Louise did it she felt less guilty. Her mom had manipulated them throughout their childhoods with impossible promises and flat-out lies (elves are real but you’ll only see one if you’re absolutely quiet for this entire car ride; I’m allergic to dogs so we can’t have one) and she’d vowed to always be honest and straightforward with her own child. Of course, the second Poppy turned out to be an early talker, Louise had adjusted her approach, but she didn’t rely on it nearly as much as her mother. That was important.

“They’re really going to cry?” Poppy asked.

Dammit, Mom.

“Yes,” Louise said. “And their pages are going to get all wet.”

Which, thank God, is when her ringtone activated, playing the hysteric escalating major chords of “Summit” with its frantic bird whistles, which meant the call came from family. She looked at her screen, expecting it to read “Mom & Dad Landline” or “Aunt Honey.” Instead, it said “Mark.”

Her hands got cold.

He needs money, Louise thought. He’s in San Francisco and he needs a place to stay. He’s been arrested and Mom and Dad finally put their foot down.

“Mark,” she said, answering, feeling her pulse snap in her throat. “Is everything all right?”

“You need to sit down,” he said.

Automatically, she stood up.

“What happened?” she asked.

“Don’t freak out,” he said.

She started to freak out.

“What did you do?” she asked.

“Mom and Dad are in a better place,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean,” he said, and carefully put his next sentence together. “They’re not suffering anymore.”

“I just talked to them on Tuesday,” Louise said. “They weren’t suffering on Tuesday. You need to tell me what’s happening.”

“I’m trying!” he snapped, and his words sounded mushy. “Jesus, I’m sorry I’m not doing it the right way. I’m sure you’d be perfect at this. Mom and Dad are dead.”

The lights went out all over Northern California. They went out across the bay. They went dark in Oakland and Alameda. Darkness rolled across the Bay Bridge, and Yerba Buena turned as black as the water lapping at its shores. The lights went out in the ferry building, the Tenderloin, and the Theater District; darkness advanced on Louise, street by street, from the Mission to the park to her building, the apartment downstairs, the front hall. The entire world went black except for a single spotlight shining down on Louise, standing in her living room, gripping her phone.

“No,” she said, because Mark was wrong about things all the time. He’d once invested in a snake farm.

“They got T-boned on the corner of Coleman and McCants by some asshole in an SUV,” Mark said. “I’m already talking to a lawyer. He thinks because it was Mom and Dad we’re looking at a huge settlement.”

This doesn’t make any sense, Louise thought.

“This doesn’t make any sense,” she said.

“Dad was in the passenger seat so, you know, he got it the worst,” Mark continued. “Mom was driving, which she totally shouldn’t have been doing because, dude, you know how she is at night and it was pouring down rain. The car rolled and it sliced her arm off at the shoulder. It’s horrible. She died in the ambulance. I find knowing these details makes it easier.”

“Mark . . .” Louise said, and she needed to breathe, she couldn’t breathe.

“Listen,” he said, soft and slurred. “I get it. You’re where I was earlier, but it’s important to think of them as energy. They didn’t suffer, right? Because our bodies are just vessels for our energy and energy can’t feel pain.”

Louise’s knuckles tightened around her phone.

“Are you drunk?”

He immediately got defensive, which meant yes.

“This isn’t an easy call for me,” he said, “but I wanted to reach out and tell you that everything is going to be okay.”

“I need to call someone,” Louise said, feeling desperate. “I need to call Aunt Honey.”

“Call whoever you want,” Mark said, “but I want you to know that everything really is going to be okay.”

“Mark,” Louise snapped, “we haven’t spoken in three years and you get drunk and call and tell me Mom and Dad are . . .” She became conscious of Poppy and lowered her voice. “. . . are not doing well but it’s okay because they’re energy? It’s not okay.”

“You should have a drink, too,” he said.

“When did it happen?”

Silence on his end of the phone. Then:

“Those details don’t matter . . .”

That triggered her internal alarms.

“Yes, they do.”

He made it sound casual.

“Like yesterday around two in the morning. I’ve been dealing with a lot.”

“Forty-one hours?” she said, doing the math.

Her parents had been dead for almost two days and she’d been walking around like nothing happened because Mark couldn’t be bothered to pick up the phone. She hung up.

She looked at Poppy kneeling on the floor by the piano bench whispering to her library books and petting them, and she saw her mom. Poppy had her mom’s blond hair, her delicately pointed chin, her enormous brown eyes, her undersized frame. Louise wanted to swoop down, gather her up, bury her face in the sweet smell of her, but that was the kind of grand theatrical gesture her mom favored. Her mom would never think that it might scare Poppy or make her feel unsafe.

“Was that Granny?” Poppy asked, because she adored her grandmother and had learned to recognize the family ringtone.

“It was just Aunt Honey,” Louise lied, barely holding herself together. “And I need to call your grandmother. You stay here and watch one episode of PAW Patrol, and when you’re done we’ll make a special dinner.”

Poppy bounced up. She was never allowed to use the iPad by herself, so the exciting new privilege distracted her from her sad library books and from who’d been on the phone. Louise got her settled on the sofa with the iPad, walked to her bedroom, and closed the door.

Mark had made a mistake. He was drunk. He had once invested thousands of dollars in a Christmas tree factory in Mexico that turned out to be a scam because he had a “gut feeling” about it. Louise needed to know for sure. She didn’t think she could stand it if she called home and no one answered, so she called Aunt Honey.

Her fingers wouldn’t go where she wanted and kept opening her weather app, but finally she managed to make them tap on Aunt Honey’s number in her contacts.

Her aunt (great-aunt, technically) picked up on the first ring.

“What?” she barked through phlegm-clogged vocal cords.

“Aunt Honey,” Louise said, then her throat closed and she couldn’t say anything.

“Oh, Lulu,” Aunt Honey croaked, and those two words contained all the heartbreak in the world.

Everything went very quiet. Louise’s nervous system made a high-pitched tone in her ears. She didn’t know what to say next.

“I don’t know what to do,” she finally said, her voice small and miserable.

“Sweetheart,” Aunt Honey said, “pack a nice dress. And come home.”

* * *

Louise’s mom also had a pathological inability to discuss death. When their uncle Arthur had a heart attack and drove his riding lawn mower through a greenhouse, she’d told Mark and Louise that she and their dad were going to Myrtle Beach for a vacation, then parked them with Aunt Honey. When Sue Estes’s older sister died of leukemia in fifth grade, Louise’s mom had told her she was too young to go to the funeral. Her friendship with Sue was never the same after that. Louise’s mom had claimed to be allergic to all pets, including goldfish, for their entire childhoods, and it wasn’t until Louise got out of grad school that her mom revealed she’d simply never wanted anything in the house that might die.

“It would have upset you and your brother too much,” she’d explained.

When Louise had Poppy, she vowed to be honest about death. She knew that stating the facts plainly would be the best way for Poppy to understand that death was part of life. She would answer all Poppy’s questions with absolute honesty, and if she didn’t know something they’d figure out the answer together.

“I’m going to Charleston tomorrow,” Louise told Poppy that night, sitting on the story-time chair beside her bed, in the glow of the plastic goose lamp. “And I want you to understand why. Your grandmother and grandfather had a very bad accident.” Louise saw safety glass exploding, metal tearing and twisting. “And their bodies got hurt very badly. They got hurt so badly that they stopped working. And your grandmother and grandfather died.”

Poppy shot up in bed, smashing into Louise like a cannonball, wrapping her arms around her ribs too tight, bursting into a long, keening wail.

“No!” Poppy screamed. “No! No!”

Louise tried to explain that it was okay, that she was sad, too, that they would be sad together and that being sad when someone died was normal, but every time she started to speak, Poppy wiped her face back and forth against Louise like she was trying to scrape it off, screaming, “No! No! No!”

Finally, when she realized Poppy wasn’t going to stop anytime soon, Louise eased herself up onto the bed and held her daughter in her arms until Poppy cried herself to sleep.

So much for explaining death the healthy way.

* * *

Louise held Poppy’s feverish, limp body for hours, wishing harder than she’d ever wished before that for just sixty seconds someone would hold her, but no one holds moms.

She remembered her mom holding her in her lap while they sat in Dr. Rector’s waiting room, where it smelled like alcohol swabs and finger pricks, distracting Louise by telling her what all the other children were there for.

“That little boy over there?” her mom had said, pointing to a six-year-old picking his nose. “He picked his nose so much that all he can smell now are his fingerprints. They’re getting him a nose transplant. And that one chewing his mother’s purse strap? They accidentally swapped his brain for a dog’s. That little girl? She ate apple seeds and they’re growing apple trees inside her tummy.”

“Is she going to be all right?” Louise asked.

“Of course,” her mom said. “The apples are delicious. That’s why they’re here. They want Dr. Rector to plant some oranges, too.”

Her mom remembered everyone’s birthday, everyone’s anniversary, everyone’s first day at a new job, everyone’s due date. She remembered every single cousin or nephew or church person’s entire life calendar like it was her job. She wrote notes, she dropped off pies, and Louise couldn’t remember a single birthday when she hadn’t picked up the phone and heard her mom singing the happy birthday song on the other end.

That was all over now. The cards on every occasion, the phone calls on every birthday, the Christmas newsletter going out to however many hundreds of people—none of it would ever happen again.

Her mom had opinions. So many opinions that sometimes Louise felt like she couldn’t breathe. The Velveteen Rabbit was Louise’s favorite book, you should never throw anything away because it could always be reused, children shouldn’t be allowed to wear black until they’re eighteen, women shouldn’t cut their hair short until they turn fifty, Louise worked too hard and should move back to Charleston, Mark was a misunderstood genius simply waiting to find his place in the world.

All those opinions, all her crafting, all her notes and phone calls, her constant need to be the center of attention, her exhausting need to be liked by everyone, her mood swings from euphoric highs to depressed lows, it made her mom who she was, but at an early age it also taught Louise that her mom was unreliable in a way her father was not.

Louise had never seen her dad upset in his life. In middle school she’d recorded Nirvana Unplugged over the video of his paper presentation at the Southern Regional Science Association. When he found out, he’d taken a long moment to absorb the information and then said, “Well, that’ll teach me to have a big head.”

When she wanted to know about electricity he’d showed her how to use an ohmmeter and they’d gone around the house sticking its test probes into wall sockets and touching them to batteries. She’d used her Christmas money that year to go to RadioShack and buy Mims’s Getting Started in Electronics, and she and her dad had taught themselves to solder, making moisture detectors and tone generators together in the garage.

Louise slid out of Poppy’s bed, careful not to wake her, and crept into the kitchen. There was something she needed to do.

She stood in the dark and scrolled through her contacts until she found “Mom& Dad Landline.” She looked away while she got her breathing under control, then touched the number.

They still had an answering machine.

“You’ve reached the Joyner residence,” her father’s recorded voice said in exactly the same rhythm she’d heard for decades. She knew every pause, every change in inflection in this entire message. She mouthed along with it silently. “We’re unwilling or unable to answer the phone right now. Please leave a clear and detailed message after the tone and we’ll call you back at our earliest convenience.”

The machine beeped, and across the country, in her parents’ kitchen, Louise heard it click to “record.”

“Mom,” Louise said, her breath high and tight in her throat. “Dad, hey. I was just thinking of you guys. I wanted to call and say hi and see if you’re there. Mark called tonight and . . . if you’re there . . . if you’re there, please pick up.” She waited a full ten seconds.

They didn’t pick up.

“I miss you both and I hope you’re okay and . . .” She didn’t know what else to say. “And I love you. I love you both so much. Okay, bye.”

She went to hang up, then pressed the phone to her mouth again.

“Please call me back.”

She hit disconnect, then stood alone in the dark. A sudden sense of certainty filled her entire body and a clear voice spoke inside her head for the first time since it had told her she was pregnant with Poppy:

I’m an orphan now.

Chapter 3

Leaving Poppy with Ian turned out to be a disaster. Poppy clung to her neck at the airport, refusing to let go.

“I don’t want you to go,” she wailed.

“I don’t want to go, either,” Louise said, “but I have to.”

“I don’t want you to die!” Poppy wailed.

“I’m not going to die,” Louise said, unwrapping Poppy’s arms from around her neck. “Not for a long time.”

She started transferring her to Ian.

“You’re going to go away and never come back!” Poppy hyperventilated, clinging to Louise. “You’re going to die like Granny and Grandpop!”

Ian took Poppy, put one hand on the back of her head, and pressed her face to his chest.

“You said they d-i-e-d?” he asked.

“I had to say something.”

“Jesus, Louise. She’s five.”

“I—” Louise started to explain.

“Just go,” Ian said. “I’ve got her.”

“But—” she tried again.

“You’re not helping,” he said.

“Bye, sweetie,” Louise said, trying to kiss the top of Poppy’s head.

Poppy pressed her face into Ian’s chest and Louise wanted to say something to make it all better, but all she could do was pick up her bag, turn her back, and walk away toward the big door marked All Gates, feeling like she’d failed at being a mother, wondering how she’d screwed this up so badly, trying to remember how her mom had explained death to her. Then she remembered: she hadn’t.

She felt slow and stupid boarding her flight. She kept wanting to apologize to everyone.

I’m sorry I can’t find my boarding pass, but my parents are dead.

I’m sorry I stepped on your laptop bag, but my parents are dead.

I’m sorry I sat in the wrong seat, but my parents are dead.

The idea felt too big to fit inside her head. It was the thought that blotted out all other thoughts. Before take off she Googled “what to do when your parents die” and was overwhelmed by articles demanding that she “find the will and executor,” “meet with a trusts and estates lawyer,” “contact a CPA,” “secure the property,” “forward mail,” “make funeral, burial, or cremation arrangements,” “get copies of death certificate.”

She wondered if she was supposed to cry. She hadn’t cried yet. She felt like she’d feel better if she cried.

Whenever Louise didn’t know what to do she made a list. As a single mother with a full-time job, lists were her friends. She opened Listr on her phone, started a new list called “To Do in Charleston,” and hit the plus sign to create the first item, then she stared at the blank line for a long time. She tried to herd her thoughts into some kind of order, but they kept slipping away. Finally, frustrated, she closed the app. She tried to sleep but it felt like fire ants were crawling all over her brain, so she pulled out her phone again, opened Listr, hit the plus sign, and stared at the first blank line until she closed it again.

At some point the plane got cold and her head dropped forward, then snapped back, then she opened her eyes and felt sweat cooling on the back of her neck. Rivulets of sweat tickled her ribs. She didn’t know what time it was. The girl next to her was asleep. A flight attendant walked by fast. The pilot made an announcement. They were landing in Charleston. She was home.

* * *

Louise walked off the plane into a world that felt too bright, too loud, too hot, too colorful. Palmetto trees and pineapple logos and walls of sunny windows and giant ads featuring the Charleston skyline at sunset all burned into her grainy eyes.

She rented a little blue Kia from Avis and drove over the new bridge to the SpringHill Suites in Mount Pleasant. SpringHill Suites processed her into their system right away and suddenly she found herself standing in a putty-colored room with peach highlights, a pineapple-patterned bedspread, and a print of palmetto trees on the wall.

She looked down at her phone. Mark still hadn’t called or texted even though she’d left him two messages the night before. Technically she’d hung up on him, but he had to cut her some slack because, after all, their parents had died. She looked at the lack of missed calls from Mark and felt disappointed but not surprised. She even felt a little relieved. She could handle it if he just showed up at the funeral and they shared a few stories, then went back to their separate lives. They had too much history to suddenly develop any kind of relationship now.

It wasn’t even noon. She needed to do something. Her palms itched. Her skin felt clammy beneath her clothes. She wanted to get organized. She wanted to get things accomplished. She had to go somewhere. She needed to talk to someone, she needed to be around people who knew her mom and dad. She had to get to Aunt Honey’s.

She got in her Kia and headed down Coleman toward the Ben Sawyer Bridge, and as she passed the hideous new development where the old Krispy Kreme used to be, she realized that she was about to drive through the intersection where her parents had died. The closer she got to the corner of Coleman and McCants, the more her foot eased off the accelerator, her speed dropping from thirty-five to thirty to just over twenty-five. She had one more traffic light. She should turn and take the connector to the Isle of Palms, but then it was too late and she was there.

Every detail leapt out at her in extreme close-up: shards of red plastic taillight scattered across the asphalt, safety glass catching the sun, a plastic Volvo hubcap crushed flat in the entrance to the Scotsman gas station. Her throat closed tight and she couldn’t force air down past her chest. All the sound dropped out and her ears went eeeeeee. The sun got too bright, her peripheral vision blurred. The light changed. The driver behind her tapped his horn. Automatically she made a right-hand turn from the left-hand lane, not even looking for oncoming traffic, realizing as she did that someone might slam into her. She didn’t care. She needed to get away from this intersection where her parents had died and see the house where they had lived.

No one hit her. She made it onto McCants and her heart rate slowed. Her chest unclenched as she came around the corner of their block, and as if a curtain was going up, she saw their old house.

Seeing it with fresh eyes, Louise saw it as it was, not dressed in its history and associations. Their little single-story brick rancher had been fine when their grandparents built it in 1951, but as the years passed, the houses around them added additions and screened-in back porches and white coats of paint over their bricks and glossy coats of black paint over their shutters, and every other house got bigger and more expensive while theirs turned into the shabbiest house on the block.

She pulled into the driveway and got out. Her rental car looked too bright and blue next to the dry front yard. The camellia bushes on either side of the front step looked withered. The windows were dirty, their screens blurry with grime. Dad hadn’t put in the storm windows yet, which he always did by October, and no one had swept the roof, where dead pine needles clumped into thick orange continents. A limp seasonal flag showing a red candle and the word Noel hung on the front porch. It looked grimy.

The first blank line from Listr appeared inside her mind and filled itself out: Walk through house. She’d start here. Do a walk-through. Assess the situation. That made sense, but her feet didn’t move. She didn’t want to go inside. It felt like too much. She didn’t want to see it so empty.

However, being a single mom had made Louise an expert at doing things she’d rather avoid. If she didn’t rip off the Band-Aid and take care of business, who would? She forced her feet to walk across the dry grass, creaked open the screen door, and grabbed the front doorknob. It didn’t turn. No keys. Maybe the back? She walked around the side of the house where the yellow grass faded to dirt, unlatched the waist-high chain-link gate, banged it wide with her hip, and slid through.

Mark’s lumber sat abandoned in the middle of the backyard, a pile of once-yellow pine faded to gray. Louise remembered how excited her mom had been when Lowe’s dropped it off for the deck Mark had promised to build back in 2017. It’d sat untouched ever since, killing the grass.

Not that there was much grass to kill. The backyard had been a blind spot in their family, a big weedy expanse of dirt and whatever mutant grass could survive without watering. Nothing significant grew out back except for a ridiculously tall pecan tree in the middle that was probably dead and a twisted cypress in the back corner, which had gone feral. A wall of unkillable bamboo separated them from their neighbors.

Louise grabbed the rattling old knob on the back door to the garage and her heart stopped. She expected it to be locked, but it turned beneath her hand and opened with a familiar fanfare of squeaky hinges. She made herself step inside.

Shadowy cousins and neighbors and aunts crowded the garage, drinking Coors the way they always did on Christmas Day, Bing Crosby playing on a boom box, the women smoking Virginia Slims, adding mentholated notes to the pink perfection of roasting Christmas ham. Louise’s eyes adjusted to the gloom and the phantoms faded and the garage looked twice as empty as before.

She walked up the three brick steps to the kitchen door and froze.

She heard the muffled voice of a man speaking with confidence and authority from somewhere inside the house. Louise stared through the window in the middle of the door, peering past its sheer white curtain, trying to see who it was.

The brick-patterned linoleum floor unrolled past the counter separating the kitchen from the dining room and stopped at the far wall, where her mom’s gallery of string art hung over the dining room table. Its plastic tablecloth got changed with the seasons, and right now it was red poinsettias for winter. The JCPenney chandelier hung overhead, the china hutch pressed itself into the corner, the chairs kept their backs to her.

The man continued talking from inside the house.

She could see a small slice of the front hall with its green wall-to-wall carpet but no people. A woman asked the man a question. Was Mark in there with a Realtor? Was he already taking stuff? Louise hadn’t seen any cars parked outside but maybe he’d parked around the corner. He could be sneaky.

She carefully turned the latch. The door cracked its seal, then swung open, and the man’s voice got louder. Louise stepped inside and eased the door closed behind her, then crept forward, ears straining, trying to figure out what he was saying. Details registered automatically—her mom’s purse sitting on the end of the counter, the answering machine blinking its red light for 1 New Message, the smell of sun-warmed Yankee Candle—then she reached the dining room and stopped.

The man’s voice sounded big and small at the same time and Louise realized it came from the living room TV. Her scalp tightened. She looked into the front hall. To the left, it got dark, leading deeper into the house. To the right was the living room, where someone was watching TV. Louise held her breath and stepped around the corner.

Hundreds of her mom’s dolls stared at her. Clown dolls on top of the sofa, a Harlequin wedged against one of its arms, German Dolly-Faced Dolls crowded a shelf over their heads, a swarm of dolls stared through the glass doors of the doll cabinet against the far wall. On top of the doll cabinet stood a diorama of three taxidermied squirrels. The TV played the Home Shopping Network to two enormous French Bébé dolls sitting side by side in her dad’s brown velour easy chair.

Mark and Louise.

That’s what her mom had called them when she bought these ugly, expensive, three-foot-tall dolls, with their hard, arrogant faces and coarse, chopped hair.

No matter where you two go, I can keep my precious babies with me forever, she’d said.

The girl sat stiffly in her layered summer frock, arms by her sides, legs sticking straight out in front, strawberry-stained lips puckered into a pout, eyes blank, staring at the TV. The boy wore a navy blue Little Lord Fauntleroy jacket with a white Peter Pan collar and short pants, and his blond hair looked like it had been hacked into a pageboy with a pair of dull scissors. Between them lay the remote. They’d always creeped Louise out.

She looked down the hall but didn’t see any other signs of life—the bathroom door was open, the bedroom doors were closed, no lights were on—so she made herself pluck the remote from between doll Mark and doll Louise, trying not to touch their clothes, and turned off the TV. Silence rushed in around her, and she stood alone in the house full of dolls.

Growing up, her mom’s dolls had mostly faded into the background. If a friend came over and said something like, “Your mom has a lot of dolls,” Louise would say, “You should see her puppets,” and then she’d show them her mom’s workroom, but mostly they went in one eye and out the other. A few times, however, like her first Thanksgiving back from college, or right this minute, she really noticed them. At those times, the house felt too crowded with dolls; there were too many unblinking eyes staring, sucking up all the oxygen, watching everything she did.

She tried to look anywhere else and immediately saw her dad’s aluminum medical cane lying on the wall-to-wall carpet in front of the TV. It was the only thing out of place in the entire room. It should have been with him in the car.

After he’d retired from the Economics Department at the College of Charleston, her dad kept finding ways to return to campus, and a year ago he’d been walking across the quad to an advisory committee meeting when a student shouted, “Professor Joyner!” and threw him a Frisbee. He’d jumped to catch it—a spectacular leap according to everyone who saw it—but the problem came with the landing. Even then, the doctors thought the real damage was done when the golf cart from public safety arrived and ran over his leg. The end result: a trimalleolar fracture and an ankle dislocation that cut off the blood supply to his foot. Three plates, fourteen pins, one bone infection, and three surgeries later they’d let him out of the hospital. Then came eight weeks of non-weight-bearing recovery, four weeks with crutches, then a CAM boot and cane for another eight weeks. While wearing the CAM boot he developed pain in his right hip, which required more PT, more MRIs, more talk of surgery.

All told, he was out of action for ten months, during which time their mom gave up her puppet ministry to sort out his pain pills, take him to PT, do PT with him, spend time with him so he didn’t get bored. Their dad had never even had a bad cold as far as Louise could remember, so this had been a seismic disruption. When Louise flew home he looked like he’d aged twenty years in a month, going from restlessly retired to complete invalid almost overnight.

He must have been watching TV when they got in the car that night and they’d forgotten to turn it off, which did not sound like her dad at all because he followed everyone around the house all the time turning the lights out after them. He must have dropped his cane, which seemed unlikely because she didn’t think he could walk very far without it.

Louise’s knees popped as she squatted to pick up the cane, and that’s when she saw the hammer. It lay on the other side of her dad’s easy chair. She got on her hands and knees to pick it up and saw the long chip of raw yellow wood along the edge of the coffee table. It looked like it had been made by the hammer.

The cane, the hammer, the TV being on, the dolls in her dad’s chair . . . it all felt wrong. She looked at the dolls. Whatever had happened, they’d seen it all, but they weren’t about to tell.

Louise propped her dad’s cane by his chair and placed the hammer on the kitchen counter before heading down the hall to the bedrooms, her feet bouncing on the green nylon wall-to-wall carpet woven for durability and sculpted into lily pads. She passed Mark’s closed bedroom door, then stopped at her mom’s workroom. It sat between Mark’s and Louise’s bedrooms, more of a large sewing room really, and over the door she’d tacked a card that read Nancy’s Workshop in cursive with a rainbow. Every night, while Mark and Louise fought over whose turn it was to clear the table or load the dishwasher, their mom retreated behind this door. She’d come out to say good night or to tell them bedtime stories, but for years Louise fell asleep listening to her mom’s sewing machine chugging away on the other side of the wall, smelling the burning-plastic stink of her hot-glue gun.

She hesitated, her hand hovering over the doorknob, and decided she wasn’t ready to face it yet. She turned and continued down the hall, then her attention snapped into focus and she stopped. Something felt off.

She scanned the walls with the eyes of an expert art appraiser, taking in the endless family photos in big frames, little frames, round frames, rectangular frames; her mom’s art (lots of her mom’s art); framed diplomas; framed programs from Mark’s high school plays; framed class pictures; framed graduation pictures; framed vacation pictures: the Joyner National Portrait Gallery as curated by their mom.

Something felt wrong. The silence of the house stretched her nerves tight. Then she realized she didn’t see the string.

They used to tuck the white string that pulled down the attic stairs behind a corner of a picture of her dad receiving an award from the National Economic Freedom Forum, otherwise it bonked you in the head when you walked by. It was gone. Louise looked up and her shoulders twitched. High in the shadows someone had done an ugly job of nailing the attic hatch closed, hammering every piece of scrap wood they could find over it and hacking off the pull-down string at its base.

It reminded Louise of the one zombie movie Ian had made her watch where people boarded up their windows to keep the zombies out. Had the springs broken and this was her dad’s terrible attempt at repair? Were there raccoons in the attic and he’d done this to keep them from getting into the house? Had taking care of her dad been too hard for her mom? Had the screens gotten dirty and had raccoons gotten in the attic and this was the best she could do? Louise felt guilty for not noticing things were getting this bad.

Standing under the boarded attic hatch made her nervous, so she headed for the end of the hall and her parents’ closed bedroom door, and stopped when she saw the big vent at the end of the hall. Its grille had fallen off, exposing the big square chopped into the drywall. She picked up the vent cover and leaned it against the wall. Had the raccoons in the attic gotten into the ducts? Had squirrels?

It felt wrong. The boarded-up hatch, the busted vent, the hammer, the cane, the TV. Her mom’s purse on the end of the counter. Something had happened right before her mom and dad had left their house for the last time. Something bad.

Her parents’ closed bedroom door and her old bedroom door faced each other and she decided to finish her walk-through and get out of there. She reached for the knob to her parents’ bedroom door and stopped. She’d open it and the room would be empty and that would feel too final. She turned and pushed open her old bedroom door instead.

Her dad had converted it into his computer room long ago. The ancient family Dell stood on her old desk, awash in a sea of her dad’s paperwork and bills. Louise automatically started to sort them. She couldn’t remember how many times she’d sorted out her dad’s desk. Almost every time she came home she hadn’t been able to sleep until she’d gotten his desk in order, and every time she came back it had reverted to her dad’s cryptic system of filing by piling.

Her movements slowed as she realized that this time his desk wouldn’t revert. This time, the papers would stay where she left them. Her dad would never scramble his paperwork again. She’d never get another out-of-the-blue, impossible-to-understand text from her mom full of random emojis and arbitrary capitalization. No more spontaneous presents for Poppy in the mail.

Louise dropped the bills back on his desk and looked at the shelves over her bed: her Wando yearbooks, the lanyard with her Governor’s School ID, her Pinewood Derby trophy from Girl Scouts, and her old stuffed animals. Red Rabbit, Buffalo Jones, Dumbo, and Hedgie Hoggie stared down at her from their shelf. She’d outgrown sleeping with them when she was five and moved them onto this shelf, where they’d become a constant, silent presence in her life. They looked so patient. They looked like they understood.

She pulled Buffalo Jones down and hugged him to her chest as she curled up on her bed, wrapping her body around his soft, uncomplaining presence. She buried her face in his white fur. He smelled like Febreze, and she felt a pang that her mom still took the trouble to keep him clean.

She’d loved these guys so much as a kid, practicing her splinting techniques on them when she was working on her first-aid badge for Girl Scouts, insisting her mom kiss each and everyone of them good night even after they’d moved to the shelf. They didn’t feel cold and silent like her mom’s weird dolls. They felt like old friends waiting for her to come home.

Whenever Louise got anxious, her dad always said, You know, Louise, statistically, and there’s a lot of variance in these numbers, but in general, from a strictly scientific point of view, everything turns out okay an improbable number of times.

Not this time, she thought. This time, nothing’s ever going to be okay again.

She hugged Buffalo Jones tight and felt something break inside her chest and tears built behind her eyes, and she grabbed onto that feeling and let it carry her away as she realized that, finally, she was going to cry.

In the living room, the TV turned itself on.

Chapter 4

five easy Flexpay installments,” a man said, his voice full of excitement. “Or a onetime payment of $136.95 gets you this beautiful, hand-crafted Scarlett O’Hara collectible doll, with her green velvet party gown, her hoop skirt, and this beautiful display case at no . . . added . . . cost.”

Louise’s body went rigid.

“That’s an amazing deal, Michael,” a woman cheered. “These dolls are moving fast, so if you want this incredible offer for this onetime price, you need to call now.”

Louise made herself stand up. She forced herself to walk to the door. She realized she still had Buffalo Jones in her arms so she put him back on her bed, then peeked around the corner into the hall. Empty.

It’s on a timer. The programming has a bug. Just go out there and turn it off.

She drew her head up, pretending to be annoyed so she didn’t feel scared, and walked toward the living room fast, the TV getting louder with every step. She entered the room and saw the Home Shopping Network playing for the blank- faced Mark and Louise dolls in her dad’s easy chair. She snatched the remote off the chair and turned the TV off.

The room full of dolls held its breath. She tossed the remote back onto the chair and stayed for a moment, making sure the TV didn’t come back on again. The Mark and Louise dolls looked snotty and bored, but of course she knew she was projecting that onto them. Dolls didn’t change their expressions.

She should get going to Aunt Honey’s. She turned and headed back to her bedroom. She’d grab Buffalo Jones and bring him home for Poppy. She could show him to her when they FaceTimed and—

“. . . want you to see this face, because it has the cool touch of porcelain but it’s actually crafted from high-quality vinyl . . .”

Louise froze halfway down the hall, shoulders hunched. She felt herself flush with irritation and embraced it so she didn’t feel her fear wriggling underneath. She spun on the balls of her feet and marched back to the living room. The Mark and Louise dolls hadn’t moved. They stared straight ahead at the TV. Louise snapped it off with the remote, then knelt beside the television and yanked its plug out of the wall.

In the sudden silence, the dolls felt restless. The ones pressing against the glass doors of the doll cabinet felt like they’d just stopped moving. One of the German Dolly-Faced Dolls on the shelf looked like she’d frozen in the middle of lifting one arm. A clown on the back of the couch looked like he could barely hold in his giggles. They were patient. They were sly. They outnumbered her.

She had to do something to show herself (them) she wasn’t afraid, so she grabbed the giant Mark and Louise dolls by their arms and lugged them into the kitchen, then out the door to the garage. They were heavier than she expected. She found a clear space on one of the big plywood shelves that wrapped around two sides of the garage and sat them on it.

Her tiny thrill of victory disappeared as the Louise doll’s hair began to quiver. The Mark doll’s hair started to vibrate. His whole body shook until he tipped over on one side, and the air throbbed now, so loud the garage rattled, and Louise turned into the noise and saw through the slit windows on the door the front grille of a giant red truck coming right for her, stopping just inches before it crushed her Kia. It sat there, rumbling.

She walk-ran back through the house to the front door, turned the thumb lock, and stepped outside to see a flatbed truck in their driveway with an enormous red dumpster on top with Agutter Clutter painted on its side. Behind it, a busted little Honda pulled up and parked on the edge of the grass, and men in white paper hazmat suits got out.

The truck engine shut off with a metallic rattle and in the sudden silence she heard a crow caw. A big man in street clothes swung down out of the cab and came toward her holding an aluminum clipboard in one hand.

“Agutter Clutter,” he said. “You the homeowner?”

“I’m . . .” Louise didn’t know exactly how to answer this question. Her parents were the homeowners. Her parents were dead. “I am.”

“Roland Agutter,” he said, holding out his hand.

Louise put her hand in his and he gave it a squeeze.

“I’m sorry,” Louise said, pulling her hand away. “You’re here for?”

“Clearing out the property,” Roland Agutter said. “I understand that what you’ve got here is a classic hoarder-type situation, but don’t panic. We’ve seen worse, believe me. What we do is we start at one end of the dwelling and move forward like a big broom, pushing everything out the front door and right into the truck. End of the day, you’ll see our taillights disappear and you won’t believe it ever looked like such a dump.”

“This is my parents’ house,” Louise said.

Roland seamlessly switched tacks.

“Their lives probably got too big for the property,” he said. “Seen it a million times. You’ll want to do a walk-through before we start to make sure everything valuable got to their new place.”

“They died,” Louise said.

It was the first time she’d said it to a stranger. The words felt like rocks in her mouth.