Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Bitter Lemon Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

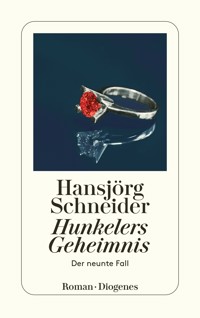

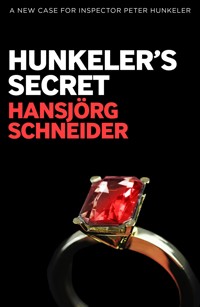

Hunkeler, now a retired inspector of the Basel police force, is hospitalized and sharing a room with Stephan Fankhauser, an old acquaintance terminally ill with cancer. One night, a groggy Hunkeler wakes up to see a young nurse with a ruby ring on her hand administering an injection to his friend. The following day Fankhauser is found dead. Was the injection just a dream?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 248

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

2

HUNKELER’S SECRET

Hansjörg Schneider

Translated by Astrid Freuler

4

The people and plot of this novel are entirely fictitious.

Any similarity to real persons and events is purely coincidental.

5

Contents

Hunkeler’s Secret

Peter Hunkeler, former inspector with the Basel City criminal investigation department, now retired, woke up and didn’t know where he was.

As he opened his eyes, he saw broad daylight. Above him was a white ceiling, and dangling down from it was something like a hand grip with a cord. The air smelled odd. Not like it did in his old farmhouse in Alsace, where it always smelled of grass and damp earth. And not like in his Basel apartment, which smelled of him, Hunkeler. The air here seemed clinically clean.

He felt calm, relaxed and pain-free. He noticed he was lying on his back. Odd, he usually slept on his side, in the foetal position. He looked up again, at the hand grip. Where had that come from all of a sudden? Who had put it there? It wasn’t hanging from the ceiling, as he’d first thought, but from a metal arm that reached across the bed. And the cord was actually a call bell.

Now Hunkeler remembered where he was. In a hospital, more specifically in a hospital bed. He’d been operated on early this morning.

He carefully ran his hands over his chest and belly. Down between his legs was something that didn’t belong there. And now it was all coming back to him. He’d been admitted to Basel’s Merian Iselin Hospital yesterday, 7 March, in the early evening. First thing this morning, he’d been given 8an injection that had sent him into a deep sleep. He had requested this, as he didn’t want to be aware of the preparations for the surgery.

At nine, he’d come round again. His girlfriend Hedwig had been there, holding his hand. Everything is OK, she had whispered. A nurse had explained that the procedure had taken just under half an hour. No carcinoma, everything was fine. Presumably, they had then transferred him to this room. He hadn’t been aware of it, he’d instantly fallen back asleep again after the good news.

“You have a catheter,” he heard a man say. “It’s not too bad, you get used to it. And as you’re drugged up, you should be feeling pleasantly pain-free. Am I right?”

“I’m not sure,” Hunkeler replied and was alarmed at his own voice. It sounded feeble and hoarse. “They’ve sliced open my belly and you’re telling me I should be feeling fine? Do you know what I would normally do with a guy who does that kind of thing to me?”

“I’m assuming by ‘guy’ you mean Dr Fahedin,” the voice came back. “He’s an internationally renowned expert. You should be grateful that it was him who operated on you and not just any old klutz.”

“I would punch him in the face. The cheek of it! Assaulting me like that while I’m asleep. A person’s dignity and integrity are sacrosanct. That’s what it says in the Human Rights Act. Does that no longer apply in hospitals?”

He could feel a distant pain in his belly; it seemed to be coming closer.

“Go ahead, shout. Or at least try to. It’ll draw you back to life. And by the way, he didn’t slice your belly open. He operated through the urethra. You’re a lucky devil.” 9

Hunkeler looked to his left, where the voice was coming from. He saw a man with a bald head and sunken cheeks sitting in the bed next to his.

“How would you know? Who are you, anyway?”

“Dr Stephan Fankhauser, pleased to meet you. And you are Inspector Peter Hunkeler. I enquired with the nurse. She told me about your operation. I must congratulate you.”

“You’re getting on my nerves,” said Hunkeler. “Can’t you keep quiet?”

“I’m afraid that’s not possible. I can’t keep quiet, I have to talk. Otherwise I’ll perish. Talking is the only form of living I have left. Only words help to stem the tide of time.”

The man laughed hoarsely.

“These are the sentences I still need to say. They sound good, don’t you think? Even though I’m talking nonsense. Do you understand?”

“No.”

“But you’re a well-educated man. You went to university.”

“How do you know?”

The man pointed to a laptop lying on the bed beside him.

“It’s all in here. You seem to be an interesting person. We should have a chat.”

“I’m not interesting. I’m a poor old sod. Can’t you see that?”

“You’re in shock after the operation, that’s all. Close your eyes, relax.”

Hunkeler closed his eyes and tried to slow his breath. Stephan Fankhauser. The name sounded familiar. “Red Steff,” he said. “I remember you from 1968. One of the biggest troublemakers of the student movement. You had hair down to your shoulders back then.” 10

“That’s right. And then what?”

“Then you joined a left-leaning law firm. Later, you became the director of the Basel Volksbank. Bourgeois through and through. And strait-laced. You should be ashamed of yourself.”

“That’s it. Go ahead and insult me if it makes you feel better.”

“It doesn’t make me feel better,” Hunkeler barked, and got a fright when the distant pain made itself felt again. He decided not to attempt any more shouting.

“And what about you, Inspector? Weren’t you a member of Basel’s leftist student group, LIST? How does that square with going on to join the CID? Back in the day, we viewed the likes of you as the henchmen of the capitalist bourgeoisie. Wasn’t that a moral conflict you struggled with?”

“Not really. I wasn’t a member of LIST, just a sympathizer.”

“So a liberal jerk who didn’t want to get his hands dirty.”

“Rubbish. Anyway, I didn’t turn into a henchman of capitalism, I was simply a man who had to earn a living. I had a family. I carried out my work as best I could.”

“And drawing a nice pension now, of course.”

Hunkeler was thinking hard. It was good, it took his mind away from this damned hospital bed. “And you?” he asked Fankhauser. “Weren’t you given the boot? For accepting large amounts of untaxed money from abroad?”

“Not at all. In our circles people aren’t given the boot. They are thanked for their excellent service and pensioned off with a golden handshake.”

“That’s not what I’ve heard.”

“Because you keep bad company. Indeed, one should only move in the very best circles. By which I mean rich circles. Because the world never changes, not even through 11revolutions. It took me a long time to realize that. Once I had, I acted accordingly.”

“I heard you received a pay-off to the tune of several million. Hush money. Enough to afford any luxury you want for the rest of your life.”

“If only I could still live a life. As you can see, that’s not possible.”

“True. Our argument is purely hypothetical. I hereby end it.”

Hunkeler closed his eyes again, but Fankhauser was persistent.

“Please don’t end our conversation. At least listen to me.”

“Why didn’t you take a private room? You could certainly afford it.”

“I did have a private room. I nearly died of loneliness. You, Inspector Hunkeler, are a gift from heaven.”

Hunkeler covered his ears. It was no good; Fankhauser’s voice was too sonorous.

“I’ve had four abdominal operations. A fifth one isn’t possible. Consequently, the cancer continues to grow. Very rapidly, by the way. And I have diabetes too. I get insulin injected twice a day. I’m basically waiting for death.”

“We’re all doing that.”

“It depends on how you’re waiting though. From a philosophical viewpoint, living is nothing more than preparing for death, as Montaigne said.”

“Not true. Montaigne said philosophizing is preparing for death, not living.”

“Wonderful, brilliant,” Fankhauser replied. “I knew you’d be good to argue with. We all carry death in us. You too, Inspector. Perhaps you’ll even die before me.” 12

“You’d be happy about that, would you?”

“No, on the contrary. I don’t have anyone, apart from my son. He visited me once. Then he rang and told me he wouldn’t be coming again. He said he can’t bear hospitals.”

“I can understand that. I can’t bear them either.”

“Just do what I do. I’m high on morphine.”

“Then I suggest you float off and stop waffling on!” Hunkeler barked.

That night, Hunkeler lay awake. A white, shimmering light hovered above him, reflected by the ceiling. It looked serene, almost magical. Evidently it was snowing outside.

It all seemed rather surreal. He felt oddly removed into a pain-free timelessness that put him in an almost cheerful mood. He heard the bell in a nearby church tower strike midnight, twelve hard, precise tolls. He heard Fankhauser muttering to himself.

“Why am I not in pain?” Hunkeler asked.

“You’re still alive, thank goodness,” Fankhauser replied. “You’re listening to me.”

“I’m not listening. I’m wondering what on earth I’m doing here.”

He propped himself up to look across at his neighbour, who was lying in bed semi-reclined.

“Don’t you ever sleep?”

“No. I go round in circles, all day and all night. The circles keep getting tighter. There’s no way out, it’s a spiral. In the end I will arrive in the centre. I will arrive in myself. That’s 13when I’ll die. But for now I’m still spinning round. And I want you to help me go round by listening to me.”

“No,” barked Hunkeler, and it already sounded more like shouting. “Spare me. I can’t be doing with all this spinning.”

Fankhauser turned his head towards Hunkeler, a bare, emaciated skull, almost lipless. He raised his right hand, it looked like the hand of a skeleton. “Please, we were at university together,” he pleaded. “We fought together, for a better world.”

“Hardly. I’m not the fighting type.”

“Oh yes you are. You come from a humble background, like me.”

“What makes you think that?”

“I can tell. We both carved out a career for ourselves.”

“Please don’t talk about me. My life is my business.”

“Why the shame?”

“I’m not ashamed. I joined the CID because I like working with people.”

“We really went for it back then, you, me, everyone involved in LIST. We gave the high and mighty of this city a proper scare. Can you remember all the daughters and sons of Basel’s richest and most distinguished families that joined us? That frightened those in power. They couldn’t exactly have the police beat up the rich kids. And do you remember the meetings we held on that estate? It belonged to a family who owned one of the big pharmaceutical companies. There we were, with Vietcong badges on our collars and the words of Chairman Mao in our pockets, and the lady of the manor brought us wine from her cellar. Do you remember that?”

Yes, Hunkeler remembered. But he didn’t reply. 14

“It’s amazing how many of us went on to climb the career ladder,” Fankhauser continued. “Parliamentarians, chief editors, directors in industry and finance. Not in the military though, but that’s falling apart anyway.”

Fankhauser’s chuckle quickly turned into a rasping cough, which he tried to suppress, probably because coughing would take too much strength.

“Look at me. I talked about the global revolution. How everything needed to change, especially the distribution of goods. I waffled on about class consciousness, about the permanent revolution, about the need to use force, to take up arms and fight. But look at Fidel Castro. He was our idol, and of course he really had taken up arms. What became of him? A run-of-the-mill dictator. And the only reason Che Guevara remained popular is because he died young. I wonder what would have become of Jesus of Nazareth if he’d grown old. Perhaps a banker with the Vatican Bank, the bank of the Holy Spirit. Eventually they all end up chasing the money, the idealists. Because money is the only form of power that counts. When I finally grasped that, I went to work for a bank. I didn’t want to work on the edge of society, I wanted to be at the centre of power. Do you understand that, Inspector?”

“Yes, but I think you should focus on saving your soul.”

“That’s exactly what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to explain to myself how I came to be where I am, lying in this bed next to yours, glad to have found a listener.”

“Well,” said Hunkeler, “I’ve definitely had enough. You’ll have to excuse me.” He reached for the bell button and pushed it.

“That’s a pity,” said Fankhauser. “If you can’t bear listening 15to me any longer, I’ll just whisper from now on. But it’s rather sad when you’re told to die wordlessly.”

The door opened. A petite woman in a white coat appeared. She was wearing a blue headscarf.

“I need a sleeping pill please,” said Hunkeler. “I can’t cope with my neighbour any more. He keeps going on and on, talking pseudo-philosophical nonsense.”

The woman nodded. Her eyes seemed to be smiling. Were they dark brown? He couldn’t quite see. Wordlessly, she took a pill from her coat pocket and gave it to him. He noticed her hand was beautifully shaped, with a small diamond ring on the middle finger. Hunkeler took the pill and washed it down with the glass of water she handed him. She nodded, smiled again and left.

“Good night then,” said Hunkeler.

The following day, Hedwig came around noon. She brought him the apples, bananas and newspapers he’d asked for.

“This hospital slop is inedible,” he claimed. “It tastes of nothing.”

“Did you try it at least?”

He shook his head in disgust. “No. One has to retain some level of autonomy in this madhouse. It’s no good caving in completely.”

She smiled at him. “Go on, have a rant, it’ll do you good. And by the way, they’re happy with how you’re doing.” She looked around the room. Her gaze fell on Fankhauser, who was lying propped up in bed as always. 16

Hunkeler saw the alarm on her face. “That’s Dr Fankhauser,” he told her. “Formerly known as Red Steff, revolutionary leader of Basel’s leftist student group, most recently boss of the Volksbank. He’s being quiet for once. He usually jabbers on incessantly.”

“Pleased to meet you, Madame,” said Fankhauser. “We rarely have lady visitors here.” He lifted his arm to shake her hand.

Hedwig backed away, startled.

“I’m sorry, Madame. I know my appearance is not particularly pleasant these days. I’ll leave you in peace.”

“What a gentleman,” Hunkeler commented. “I know him from university. He’s in a pretty bad way.”

There was a violent coughing by way of reply, followed by a wheezy grunt.

“I’m supposed to go for a walk with you,” said Hedwig.

“What? Are you mad? I can barely stand.”

“The nurse told me to, so come on.” She pulled him up.

He looked out the window, it was snowing heavily out there. “I’m not going outside with that snowstorm going on,” he insisted.

“Nobody expects you to. We’re going to take the stairs up to the cafeteria. Come on, get dressed.”

Out in the hallway she hugged him tight. Her arms were trembling.

“What’s the matter with you?” he asked. “Who’s the patient here, me or you?”

“It gave me a fright, Peter. That man looks like a living skeleton. He even wanted to shake my hand.”

He stroked her hair. “It’s not all that bad. I think he’s quite glad to be dying. But us two, we’ll manage to struggle on for a while yet, won’t we? Now let’s go, I need a coffee.” 17

Up in the cafeteria they sat down by a window facing west. The snow had stopped falling and the sun was breaking through the clouds. A surreal light set everything aglow, the roofs of the city, the nearest hill across the border in Alsace, the white water tower of Folgensbourg.

“Beautiful,” said Hunkeler. “Actually, I’m feeling fine again already. We could drive straight over to our house this evening, light the fire and drink a bottle of wine.”

“You’re staying here for as long as the doctors tell you to,” she replied.

“I can’t stand much more of the guy in the other bed. He’s spewing out his entire past, right in front of my feet. Even though I’m not the slightest bit interested. But he’s merciless.”

She lowered her gaze and went quiet.

“What’s up?” he asked.

“Your daughter Isabelle has asked me to pass on her regards.”

He was taken aback. He hadn’t been expecting that.

“She says she hopes you get well soon.”

Isabelle, whom he hadn’t seen for years. Who had distanced herself from him early on and had completely cut ties at eighteen.

“Aren’t you pleased?”

“I am. But I don’t want to talk about it. Or rather, I can’t.”

The last he’d heard from her was that she had given birth to a daughter called Estelle and had moved to a village in the Vosges mountains.

“You mean you don’t want to.”

“Perhaps. I don’t like thinking back to that time.”

“That’s a pity.” 18

“Why?”

“Because it interests me.”

“Isabelle was my open wound for a long time. It only healed when I met you. Really, it’s true. You helped me get over it.”

He reached to take her hand, but suddenly grew suspicious.

“Anyway, what exactly is going on? I mean, how did you find her?”

“I rang her and told her that you were having an operation.”

“What? Behind my back?”

“Well of course. What do you think? You can’t bury your past, it won’t work.”

He stared at her in disbelief. But he stood no chance against her resolve.

“So, are you saying you regularly speak to her? And since when?”

“Ever since you told me about her.”

“And all in secret, without a single word?”

“Of course. Someone has to be sensible here.”

Towards evening, Hunkeler got a visit from Madörin, former detective sergeant, now Hunkeler’s successor as inspector. They hadn’t seen much of each other since Hunkeler had retired. He’d been avoiding Madörin. He simply didn’t like the guy. His squat, stocky figure, his hangdog look. He knew Madörin was a capable criminal investigator. But Hunkeler had always felt that being a good inspector required more than just tenacious implacability, it required kindness and compassion towards people. 19

Now Madörin was standing next to Hunkeler’s hospital bed with a bunch of flowers in his hand. He clearly felt embarrassed, seeing his former boss lying there in his nightshirt. “I’m bringing you these flowers on behalf of the CID,” he announced. “With best wishes for a speedy recovery.”

“Thank you.”

“In particular Corporal Lüdi and Haller send their regards.”

Madörin looked around the room for somewhere to put the flowers.

“Lay them on the table,” Hunkeler instructed. “Personally, I think flowers in a hospital are intolerable. They remind me of funerals.”

Madörin did as he was told, indignantly shaking his head. He didn’t like being bossed around.

“And Prosecutor Suter?” Hunkeler asked.

“He sends his regards too. I spoke to him on the phone. He’s currently at a conference in Cologne. And warm wishes from Frau Held at reception.”

“Thank you.”

It was all Hunkeler could say, even though he would have liked to be a little more friendly. He felt touched, thinking of the many years they’d spent together, the power battles they’d fought, most of which he’d won, the successful investigations and the failed ones.

“Nice room you’ve got here,” said Madörin. “Quite luxurious.” He looked around, distrustful and aloof. He was always on duty. “Who’s that?” he asked, glancing across to the other bed.

“Dr Fankhauser, former director of the Basel Volksbank,” Hunkeler told him. “I’m sure you’ve heard of him.” 20

Madörin furrowed his brow, as always when he was thinking hard. “Oh yes.” And to Fankhauser, “How are you?”

“Commensurate with circumstances, thanks,” Fankhauser replied. “I assume you’re from the police?”

“Yes, CID. Actually, we’ve just received a report stating that Viktor Waldmeier has been arrested while entering the US. He’s your successor at the Volksbank, isn’t he?”

A gentle smile spread across Fankhauser’s face, a hint of vitality. “Ah, Viktor. I knew he’d slip up on one of his deals one day. But what do they expect from us? Everyone wants to earn money from the banks. But when a deal backfires, we bankers have to take the fall. By the way, if you want to arrest me, go ahead, be my guest.” He gave a wheezy laugh, which turned into an agonizing cough.

“Stop it,” Hunkeler told Madörin. “Leave him in peace, he’s in a really bad way.” Then, very quietly, “Is that true about Waldmeier?”

“Yes, at Kennedy Airport in New York. But it’s not official yet.”

“Well I never.”

“Yes, old pal, quite a lot has changed since you left. We’re interlinked like crazy, in every direction, with every possible service. Good clean police work has gone out of fashion. Just be glad you’re not involved any more.”

Was he gloating now, or did he mean it?

“I really mean that, by the way. Honest. Sometimes I miss you.”

21Hunkeler had eaten two bananas and an apple. The bananas had tasted great, unlike the apple. It was one of those new varieties and looked like it was straight out of the Garden of Eden: red-cheeked, yellow-speckled and bursting with juice. But biting into one of these overbred beauties was like walking into a hair salon. It tasted of perfume. And cheap perfume at that. No character, no acidity, nothing. As interchangeable as the numbskulls that ate these things. And now he, Hunkeler, was one of them.

He grinned bitterly at the thought. He felt ancient. Like a fossil from the third day of creation, when the Almighty had separated land from sea; a relic that had surfaced and landed right here in this hospital bed. He looked across at his neighbour, who was lying with his knees bent up and muttering incomprehensibly. So that’s what progress looked like when the end was near. Lying in a bed, in an unfamiliar room. Being cared for by strangers whose names you don’t know. Like that petite young woman, of whom Hunkeler couldn’t even have said what colour her eyes were. And you’re grateful if an old inspector is in the next bed, someone you can exchange a few words with. Then, when you’re finally dead, you’re shunted out of the room and into the elevator that takes you down to the morgue. Hours later or perhaps two or three days later, depending on how many corpses are accruing, you’re incinerated somewhere or other. And not a word about it, done and dusted.

Hunkeler felt out of place. Like a vegetable, a carrot that due to a silly system fault has ended up in the compartment for frozen meat, wrapped in plastic, neatly vacuum-packed. He would have liked to remove the catheter and quietly abscond. But was that even possible? Wasn’t the 22reception desk staffed around the clock, to intercept fleeing patients?

He thought about Madörin claiming that he missed Hunkeler. Was he really being missed? Wasn’t it the other way round? That Hunkeler was longing for Madörin, even though the man annoyed him? Perhaps that’s what Hunkeler was hankering after. The power battles, the daily arguments.

He turned his head to the bedside table and looked at the alarm clock. Half past twelve, middle of the night. He listened, wondering if he could pick up any other sounds apart from the constant mumbling from the other bed. Footsteps, voices, a shout. Nothing – the entire hospital seemed to be asleep.

“The time one has lived continually increases,” said Hunkeler. “And the time one still has to live perpetually diminishes. That’s a platitude, but it’s the sad truth.”

“Thank goodness,” Fankhauser said. “You’re still here. You’re listening to me.”

“I’m not. I’m just saying that this erosion starts way back in childhood. But you’re not aware of it yet, because you’re happy to be getting older. It’s a different matter once you’re old. You brace yourself against the passing of time, even though that’s ridiculous, because time passes anyway.”

“I’ve heard you have a daughter.”

Hunkeler hesitated, wondering whether to answer or not. “Yes, sort of.”

“And? Were you a good father?”

“No. Our paths separated quite early on.”

“You see? The only thing that was important, you failed at. I’m currently enumerating all my failings. I have a whole list of them. I keep reciting them to myself to make sure I’m 23still alive. The list grows longer every time. I’m wallowing in my faults. Perhaps human life is nothing but a big mistake, who knows?”

“Nonsense. You should be ashamed of yourself,” said Hunkeler.

“Why?”

“Because there is no true life within a false life, as Theodor Adorno said. Have you forgotten that? Besides, we all rejected the nuclear family because we saw it as a capitalist tool for domestication.”

“And yet you got married?” Fankhauser wondered.

“Yes. We wanted to give it a go. Also, my girlfriend was pregnant. It was expected of us that we marry.”

“And where is your former girlfriend now?”

“She died a few years ago.”

“And your daughter?”

“She lives in the Vosges mountains, as far as I know.”

“So you alienated yourself from your own daughter.”

“Nonsense. I let her get on with her life. I hope she’s happy.”

From outside, a church clock could be heard striking.

“Do you really never sleep?”

“No,” said Fankhauser. “I need to do my calculations. In the end, when I die, I have to know the score. Debit and credit. Do you understand? There’s a lot listed under debit, almost nothing under credit.”

“Despite your millions?”

“Oh come on, money is muck. The more you have of it, the dirtier it makes you.”

“That’s not true. Only those who don’t have any money have to get their hands dirty when they work. You don’t. And 24I’m sure you don’t live in the narrow streets of Kleinbasel, among the Turks and Albanians. You probably live up in the clean air of the Bruderholz district.”

“Yes, except that now I live here in this hospital room, lonely and forsaken. Apart from you, of course. And I’m very grateful to you for that.”

“You’re welcome. But I’m afraid that’s it for now. I need to get some sleep.” Hunkeler reached for the bell button and pushed it.

“Do you know who I’m bequeathing my money to?” Fankhauser asked. “Are you curious?”

“Your son, I assume.”

More coughing from Fankhauser, followed by a terrible rasping wheeze.

“Wrong. He’s only getting the compulsory share. I’ve bequeathed everything else to Basel Zoo. My son will be surprised when he hears that. He will curse me. But that’s what I’m like. Society has made me what I am. A monster. This, it would seem, was my destiny in late capitalism. Zero solidarity, zero comradeship. Homo homini lupus. Man is a wolf to another man. A rapacious, fierce animal that attacks members of its own species. Do you understand what I’m saying, Inspector? Say something, answer me. Do you think I’m a monster too?”

“I think it serves Viktor Waldmeier right,” Hunkeler replied. “It’s about time some of your kind are convicted and locked up.”

Again the terrible rasping wheeze, the gasping for air.

“Wrong, you’re totally wrong. You’re still fantasizing, Inspector. Waldmeier will never be convicted. He knows too much. He’s not stupid, he has something up his sleeve. 25He will sell his inside knowledge, the bank data he’s bound to have with him. He’s going to sell it to the Americans for millions of dollars and betray the Volksbank without batting an eye. Then he’ll retire and lead a jolly life somewhere by a pleasant beach.”

This was simply too much for Hunkeler. “Who’s in charge in Switzerland?” he shouted. “Us or the Americans?”

“See, I knew it,” said Fankhauser. “You’re ranting like a proper Swiss. Good, very good. But completely ineffective, because the stronger side rules. And the weaker side has to obey. The Americans are stronger. It’s as simple as that.”

“We have direct democracy in Switzerland,” Hunkeler objected. “In a direct democracy, the people rule. It’s the people who decide which rules apply in Switzerland and which don’t.”

Hunkeler was a little surprised at the words that were spilling out of him. But he was speaking from the bottom of his heart. When all was said and done, he firmly believed in the Swiss democratic system.

“A proper old-school Swiss confederate,” Fankhauser observed. “Glad to hear it. But you know yourself that it’s pure folklore.”

“No,” Hunkeler disagreed. “Switzerland is a free, sovereign nation. That’s a fact.”

Fankhauser seemed to delight in the heated discussion. He chuckled wheezily. “A Swiss confederation in which everyone stands side by side, collectively discussing and deciding what should be done. How lovely,” he remarked. “But this federation has long gone, it only exists in our dreams and imagination. Perhaps it still works on a local level, when the good citizens go and vote on the increase in dog tax 26and suchlike. Fair enough. But the important decisions that affect Switzerland are no longer made in this federation, they haven’t been for a long time. Even our banks, which count among the most powerful financial institutions in the world, are no longer free to make their own decisions. It’s the Americans who dictate the rules for the Swiss banks. Nobody gives a damn whether that’s fair or not.”

Hunkeler didn’t respond. He felt too tired and washed out.

“Years ago,” Fankhauser continued, “if you wanted to make a lot of money, you had to set up your own bank. That’s no longer necessary. Now you just have to work in a bank. Then you can steal confidential data and sell it abroad for lots of money. And that’s exactly what Viktor Waldmeier is going to do.”

“Enough talk. I want to sleep now.”

“OK, I’ll leave you in peace. But I’d like to thank you for the stimulating discussion.”

A little later, the door finally opened and a petite woman in a white coat appeared. She was wearing a blue headscarf, like the previous night.

“I need a sleeping pill,” Hunkeler told her. “A strong one, please. What’s your name, if I may ask?”

She placed her index finger on her lips. A faint scent of cinnamon surrounded her. It was barely detectable, but distinct.