Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

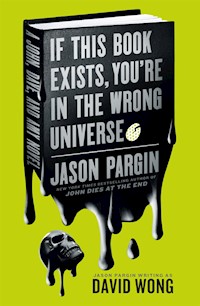

A standalone darkly humorous thriller set in modern America's age of anxiety, by New York Times bestselling author Jason Pargin Outside Los Angeles, a driver pulls up to find a young woman sitting on a large black box. She offers him $200,000 cash to transport her and that box across the country, to Washington, DC. But there are rules: He cannot look inside the box. He cannot ask questions. He cannot tell anyone. They must leave immediately. He must leave all trackable devices behind. As these eccentric misfits hit the road, rumors spread on social media that the box is part of a carefully orchestrated terror attack intended to plunge the USA into civil war. The truth promises to be even stranger, and may change how you see the world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 672

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also by Jason Pargin and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Day 1

1Abbott

2Abbott

3Hunter

4Abbott

5Key

6Malort

7Abbott

8Key

Day 2

9Abbott

10Abbott

11Key

12Abbott

13Abbott

14Malort

15Abbott

Day 3

16Abbott

17Ether

18Zeke

Day 4

19Ether

20Abbott

21Key

22Hunter

23Ether

Day 5

24Zeke

25Abbott

26Abbott

27Ether

28Malort

29Key

30Abbott

31Abbott

Afterword

About the Author

Also by Jason Pargin and Available from Titan Books

ALSO BY JASON PARGIN AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

The Zoey Ashe series

Futuristic Violence and Fancy Suits

Zoey Punches the Future in the Dick

Zoey Is Too Drunk for This Dystopia

The John, David and Amy series

John Dies at the End

This Book is Full of Spiders: Seriously Dude, Don’t Touch It

What the Hell Did I Just Read?

If This Book Exists, You’re in the Wrong Universe

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

I’m Starting to Worry About This Black Box of Doom

Print edition ISBN: 9781835412695

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835412701

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Jason Pargin 2024

Jason Pargin asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

FOR MY MOTHER, WHO GAVE EVERYTHING TO EVERYONE

DAY 1

But I am very poorly today and very stupid and hate everybody and everything.

—CHARLES DARWIN, in a letter to a friend, 1861

1

ABBOTT

Abbott Coburn had spent much of his twenty-six years dreading the wrong things, in the wrong amounts, for the wrong reasons. So it was appropriate that in his final hours before achieving international infamy, he was dreading a routine trip he’d accepted as a driver for the rideshare service Lyft. The passenger had ordered an early-morning ride from Victorville, California, to Los Angeles International Airport, a facility Abbott believed had been designed to make every traveler feel like they were doing it wrong.

He rolled up to the pickup spot—the parking lot of a Circle K convenience store—to find a woman sitting on a black box, one large enough that she probably could’ve mailed herself to her destination with the addition of some breathing holes and a piss drain. It had wheels, and she was rolling herself back and forth a few inches in each direction with her feet, working out nervous energy. The millions of strangers who would become obsessed with that box in the coming days would usually describe it incorrectly, calling it everything from a “footlocker” to an “armored munitions crate.” What the woman was actually sitting on was a road case, the type musicians use to transport concert gear. This one was covered in band stickers, a detail that would have been inconsequential in a rational society but would turn out to be extremely consequential in ours.

Abbott rolled down the window and braced himself, doing his usual scan for reassuring signs that the passenger is Normal (he’d developed a sixth sense for the weirdos who, for example, wanted to sit in the front). The woman on the box wore green cargo pants and a dazzling orange hoodie that looked to Abbott like high-visibility work gear. Though, if she were on the job, the bosses weren’t strict about the dress code: She wore a faded trucker cap that said, WELCOME TO THE SHITSHOW. Below that was a pair of oversize sunglasses with lime-green plastic frames and, below that, smeared lipstick that looked like it had been hurriedly applied in the dark. Her hair was short enough that it appeared to have been buzzed without a mirror while driving down a bumpy road. It did not occur to Abbott that all of this would be an excellent way to thwart security cameras and facial recognition software.

Abbott, his nervous system already hovering a finger over its big red Fight-or-Flight button, asked, “You got the Lyft to LAX?”

He was hopeful she’d say no, but there was no one else in the vicinity aside from a rail-thin man by the tire air machine having a tense argument via either Bluetooth or psychosis.

“Oh my god,” said the woman on the box, “I have a huge favor to ask you. HUGE. I am in so much trouble with my employer.”

She removed her green sunglasses as if the situation had become much too serious for such eyewear. Her eyes were bloodshot, and Abbott thought she’d either been recently smoking weed or recently crying, though he knew from personal experience that it was possible to do both simultaneously. He was now absolutely certain that the favor she was about to ask was going to be illegal, impossible, or just a string of nonsense words. He wasn’t sure how to respond without accidentally agreeing, so he just stared.

“Okay,” she said, after realizing it was still her turn to talk. “Yes, I ordered a trip to LAX, but in the time I’ve been waiting, I found out that’s not going to work. This is a big problem. BIG problem.”

Her voice was shaky, and Abbott decided that she had, in fact, been crying. He instantly sensed two opposing instincts in his brain quietly begin to go to war with each other.

“This box I’m sitting on?” she continued. “The guy who hired me has to have it by Monday, the Fourth of July. I can’t ship it, because I can’t let it out of my sight—I have to stay with it, wherever it goes. And I can’t fly, for reasons that would take all day to explain. Now, I’m going to ask you a question. It’s going to sound like a hypothetical or a joke, but it’s an actual question. Okay? Okay. So, how much would you charge to drive me to Washington, DC?”

Abbott took a moment to make sure he’d heard her right before replying, “Oh, that’s not something you can do in a Lyft; the maximum trip is only—”

“No, no. You’d clock out of your app or however you do it. I’m asking you, personally, as a citizen with a beautiful working car—what is this, an Escalade?”

“A, uh, Lincoln Navigator. It actually belongs to—”

“I’m asking what you would charge to take me all the way across the country. And your reflex is going to be to say no amount of money because I’m talking about totally putting your life on hold for more than a week, without notice. Restaurants, hotels, lost business, canceled Fourth of July plans, additional stress—it’s a lot to ask. But I’m willing to pay a lot. Or rather, my employer is willing to pay a lot. Look.”

She twisted around and dug into a tattered duffel bag that Abbott hadn’t previously noticed. When she came back around, she was holding two thick folds of cash, each bound with rubber bands. He physically recoiled at the sight of it, mainly because not a single reasonable person has ever carried money that way.

“This is one hundred thousand dollars,” she said, waving the cash around like a mind-control amulet. “The guy who hired me has this kind of money to throw around, and no, he’s not a criminal, he’s a legitimate rich guy, if such a thing exists. No, I can’t tell you who he is. All I can tell you is that he needs this box by the Fourth at the latest, and it has to be kept quiet. Today is Thursday. We can make it easily; we don’t even have to travel overnight. Four days of leisurely driving and we’ll get there Sunday evening, no problem. One hundred K is my starting offer for you to make this drive. Make me a counteroffer.”

At this stage, Abbott was considering this request in the exact same way he’d have considered a request to be transported to Venus in exchange for a baggie of rat turds: He just wanted out of the crazy conversation as quickly and safely as possible.

He said, “I’m sure there are plenty of people within a few miles of here, probably a million of them, who’d love to take you up on this. But I really can’t. I’m sorry.”

She shook her head. “No. No, you’re perfect for this, I can tell already. And I can’t keep asking people; I have to get on the road, and I have to do it now. The more drivers I have to ask, the more people know about this, and that’s bad. Secrecy is part of what I’m paying for. And I’m not crazy, I know how I look. Though I will have to tell you about the worms at some point. But no, I’m dressed like this for a reason. How about one fifty?”

A third fold of cash was added, and Abbott had to force himself to look away from it. He prided himself on not being enslaved to mindless greed, but way back at the rear of his noisy brain was a tiny voice pointing out that this amount of money would let him move out on his own and tell his father to fuck off (though it would definitely have to be done in that order). It would be freedom, for literally the first time in his life. He imagined a factory farm pig escaping into a sunny green pasture and seeing the clear blue sky for the first time. Though he was having trouble imagining the pig looking up. Could pigs do that? He’d have to google it later. Wait, what did she say about worms?

The woman grinned and sat up straighter, the posture of an angler who’s just seen the bobber plop under the surface. It kind of made Abbott want to refuse just to spite her.

“But there are rules,” she said, a finger in the air. “You can’t look in the box. You can’t ask me what’s in the box. And you can’t tell anyone where we’re going until it’s over. After that, you can tell anyone anything you like. But no one can come looking for us.”

“Well, there’s certainly nothing weird or suspicious about that. So, why don’t you just rent a car and drive yourself?”

“No driver’s license. I used to have one, but the government took it away. They said, ‘You’re too good of a driver, it’s making the other drivers look bad, you’re hurting their self-esteem.’”

“I just . . . I really can’t, sorry. You say I’m perfect for this, but I assure you I’m the absolute perfect person to not do it. That’s, what, like, fifty hours of driving? I don’t even like to drive for one hour.”

“You drive for a living!”

“Oh, I just started doing this a couple months ago to—”

“I’m just teasing you. I know you probably didn’t grow up dressing as a Lyft driver for Halloween. But no, you’re my guy. You’re not married, right? I don’t see a ring. No kids, I can see it on your face. If you have another job, it’s one you can walk away from; it’s not a 401(k)-and-health-insurance situation. You probably live with a parent, so even if you have pets, there’s somebody to feed them while you’re away. You’re old enough that nobody’s going to assume you were abducted. You’re, what, twenty-four? Around there?”

“Twenty-six. Did you just deduce all that on the fly?”

She smiled again and made a show of leaning forward, narrowing her eyes as if to examine him. “Ah, see, there’s something you need to know about me: I can read minds. I can tell you’re skeptical, so let me give it a shot. Ready?”

She narrowed her eyes farther, comically exaggerating her concentration. At this point, Abbott was 99 percent of the way to driving off and marking the ride as canceled.

“You have trouble getting to sleep at night,” she began, “because you can’t turn off your brain. Usually, it’s replaying something stressful that happened in the past or rehearsing something stressful that could possibly happen in the future. You then have to down constant caffeine just to function through the day—I bet you’ve got one of those big energy drinks in the center console right now. You sometimes get really good ideas in the shower. You can’t navigate even your own city without software that gives you turn-by-turn directions. You get an actual, physical sense of panic if you can’t find your phone, even if you know it’s still somewhere in your home.”

She was rocking in her seat, rolling the trunk’s tiny wheels back and forth, back and forth.

“You don’t have a girlfriend or a boyfriend,” she continued before Abbott could interrupt. “You’ve never had a long-term relationship, and at least once in your life, you thought you were dating someone while the whole time they thought you were just friends. You actually don’t have any close friends. Maybe you did when you were in school, but you don’t keep in touch. You’ve replaced them with a whole bunch of internet acquaintances—maybe you’re all members of the same fandom or a guild in a video game—but you’d be traumatized if any of them suddenly showed up at your front door unannounced. Sometimes, out of the blue, you’ll physically cringe at something you said or did when you were a teenager. When you use porn, you may have to sort through two hundred pics or videos before you find one that will get you off. You’re sure that humanity is doomed and feel like you were cursed to be born when you were. Am I close?”

Abbott had to take a moment to gather himself. Forcing a dismissive tone with all his might, he said, “Congratulations, you’ve just described everyone I know.”

“Exactly. It describes everyone you know.”

“I really do have to get back to work, I don’t—”

“Don’t get offended, please, none of that was intended as an insult. I’m only saying that I know you’re an outsider, just like me! I think the universe brought us together. But I’m not done, because this is the big one: The reason you’re hesitating to make this trip, even for a life-changing amount of money, isn’t because you’re worried that I’m a scammer or that my employer is a drug lord and this box is full of heroin. No, what you fear above all is humiliation at the hands of the unfamiliar. What if you get a flat tire on a highway in Tennessee—do you even know how to change it? What if we wind up in the wrong lane at a toll road and the lady in the booth yells at you? What if you get a speeding ticket in Ohio—how do you even pay it? What if you get into a fender bender and the other driver is a big, scary guy who doesn’t speak English? Then there’s the absolutely terrifying prospect of spending dozens of hours in an enclosed space with some weird woman. What if you embarrass yourself? Or, worse, what if I say something that makes you embarrassed on my behalf? You’ll have no mute or block button, just unfettered raw-dog, face-to-face contact, with no escape, for days on end. What if I’m so unhinged that we literally have nothing to talk about, no shared jokes, no way to break the tension? What if, what if, what if—all of these scenarios that humanity deals with a billion times a day but that you find so terrifying that you wouldn’t even risk them for a hundred and fifty thousand dollars in cash. So the question is: Would you do it for two hundred?”

She fished out a fourth hunk of bills. The escalating amounts actually didn’t make an impression on Abbott; at this point, the dollar figures all registered as equally impossible sums of money. But the hand that held the cash was trembling, and he sensed the thrum of desperation inside the woman, the vibe of one who has exhausted every reasonable option and is now trying the stupid ones.

“A hundred now,” she said, “and a hundred after we arrive in DC. If you think it’s a trick, that we’ll get there and I’ll steal back the money at knifepoint, we can swing by somewhere and you can drop off the first payment. You can even take it to your bank, let the teller do the counterfeit test on the bills. If we hurry.”

“How do you know I wouldn’t do that and then just refuse to drive you?”

“Because I can see into your soul. You would never do that. Not just because it’s wrong but because you’d be torn apart by the awkwardness of that conversation, of having to see the look on my face when I found out you’d double-crossed me. Also, you’d soon realize that you wouldn’t just be screwing me but my employer. And even if he’s not a criminal, you can guess that’s probably a pretty bad idea. He could send guys in suits to your house to demand the money back, and just think how awkward that would be.”

Abbott heard himself say, “Can I have time to think about it?” and knew that his automated avoidance mechanism had kicked in. He’d been developing this apparatus since his first day in kindergarten when the Smelly Girl had asked him to play with her and, in a panic, he’d had to come up with a plausible excuse not to (he told her his family’s religion forbade touching plastic dinosaurs). These days, it was pure reflex: If an acquaintance invited him to trivia night at the bar, a ready-made, ironclad excuse would fly from his lips before he’d even given it a thought. Sure, sometimes he’d find himself wondering if maybe he should be filtering these invitations before they were routed directly into the trash. Here, for example: On some level, he knew this offer deserved more consideration. But his request for time wasn’t about that, it was just one of the stock phrases he deployed to get to a safe distance where plans could be easily canceled via text or, even better, by simply avoiding that person for the rest of his life. Sure, this woman was in some kind of distress, but that would be no burden to him once she was out of sight—

“No, you can’t have time to think about it,” said the woman on the box. “I meant it when I said we have to leave right now. Maybe we can swing by your place to pack up some clothes and whatever medications you’re on—you’re on a few, right?—and to tell the parent or grandparent you live with that you’ll be back late next week. But it has to be real quick, in and out.”

“I can’t even tell my dad where I’m going?”

“You’ll tell him that a friend needs you to help with a job that pays a bundle, that it’s being done on behalf of a celebrity and has to be kept quiet so the press doesn’t sniff it out. And that it’s nothing illegal. That’s, like, ninety percent true. Or eighty percent. It’s mostly true.”

“Is your employer a celebrity?”

“He’s not a movie star or anything, if you’re trying to guess who he is. But your dad shouldn’t question it.” She waved a hand in the vague direction of Los Angeles. “Out there, you’ve probably got a hundred professional fixer types doing jobs like this as we speak.”

“Then go find one of them. If you think I’m such a loser, what makes you think I can even get us there?”

“All right, enough of that.” She stood and put on her lime-green sunglasses. “You don’t even have your heart in it anymore. Come on, help me load the box. It’s really heavy. We’ve been sitting out here too long, and people are starting to stare.”

In the coming days, many words would be spent speculating as to why Abbott had agreed to the trip. Was it the money? Or did he genuinely want to help this woman he’d never met? The truth was, not even Abbott himself knew. Maybe it was just that by the time she was lugging the box toward the rear of the Navigator, it’d have simply been too awkward to stop her.

MALORT

Considering he was 275 pounds, bald, covered in tattoos, and wearing mirrored sunglasses, Malort could have wound up with many nicknames. But a drunken bet in a Milwaukee dive bar decades earlier had resulted in a bicep tattoo of a Jeppson’s Malört bottle, the Chicago-area liquor so infamously bitter that the label featured a lengthy paragraph apologizing for the taste. His friends had all agreed the tattoo and nickname fit him, but never dared to explain their rationale in his presence. He did have to drop the little dots above the o in recent years, as nobody knew how to add those in text messages.

The man they called Malort rolled up to find that the Apple Valley Fire Department had apparently arrived just in time to turn the shack in the desert from a smoldering ruin into a wet smoldering ruin. Only two and a half walls of the flimsy structure were still upright, exposing the charred interior like a diorama. It told a fairly simple story of a loner hiding from and/or rooting for the apocalypse. From where he sat, there was no sign of the black box, and he had a sinking feeling it was long gone.

He stepped out of his metallic red Buick Grand National and approached a young man whose build and face made him look like a kid who’d dressed up in his dad’s helmet and turnout coat. He was hosing down the aftermath to cool the embers and looked like he would have a stroke if two thoughts appeared in his brain simultaneously. He noticed Malort, and a beam of curiosity pierced his haze.

“This your property?” asked the kid.

It was a dumb question, thought Malort. The type of guy who sets up in a wilderness survival shack probably doesn’t get around in a sparkly Buick that surely lists at least one pimp in its CARFAX report. He took the dumbness of the question as a good sign. Instead of answering, Malort pulled out his phone and pointed the camera at the scene, acting like he had an important job to do. Generally, if you can project enough confidence and purpose, all the uncertain nerds of the world will just part like the Red Sea.

He stepped toward the smoldering structure with his phone and, without looking at the kid, grumbled, “Is there propane?”

“There was. It already popped; that’s what blew out the sides here. The ruptured tank is on the floor. There’s some kind of apparatus attached. Maybe a booby trap, or maybe they were trying to deep-fry a turkey? You ever seen one of those go wrong? Nightmare. So, uh, are you a friend? One of the neighbors?”

Malort peered into the half-standing structure from afar, trying to stay out of the hose splatter. The other firefighters hadn’t seemed to register his presence, most of them distracted by the task of spraying down the landscape to keep stray sparks from triggering a brush fire.

“The strangest thing just happened,” rumbled Malort. “You know the big house over the hill there, behind the fence with all the barbed wire? The crazy bastard who lived there owns all this, it’s all his property. So, I was chasing an intruder through that house, then they went round a corner and vanished into thin air. I looked all around, saw neither hide nor hair of ’em. A few minutes later, I looked out the window and noticed the smoke over here.”

“Oh, really?” said the kid, who didn’t seem to understand what that had to do with this.

“Nobody dead in there, I take it?”

“No, sir. Looks to me like they either left the propane to blow on purpose or left it unattended on accident.”

“So there’s no corpse in there, but if you go over the hill and look in that house behind the barbed wire, you’ll see the owner is dead on the floor of a workshop where he was making Lord-knows-what. Though I wouldn’t advise poking your head in unless you’ve got a strong stomach. They’ll have to identify him by his teeth and prints, considering the condition his face is in.”

Malort studied the smoking remains of a bed, now just a blackened frame and springs. The morning sunlight and the spray of the hose was decorating the scene with a festive little rainbow.

“Is that true?” asked the kid, trying to piece together the implications. “Did you call it in?”

“I’m not much for callin’ things in. Though you should tell your people to wear protective gear when they go over there. I don’t know what the guy had in his shop, but there were homemade radiation warning signs on the door. You can decide for yourself whether a homemade radiation sign is scarier than an official one.” Malort studied the shack’s exposed ashy guts and asked, “Have you seen any sign of a road case? One of them black boxes with aluminum trim, about the size of a footlocker?”

“No, sir. I mean, we haven’t dug around inside there, but I haven’t seen anything like that. Hey, uh, Bomb and Arson are on their way. You should tell them about the dead body.”

“Nobody has come to take anything from the scene?”

“Not since I been here. I didn’t catch your name?”

“And nobody saw the occupant leave? Or what vehicle they were driving? Might have been a blue pickup.”

“No, sir.” The kid was glancing around now, presumably for someone senior to come to his rescue.

Malort zoomed in with his camera, focusing on the bit of intact wall at the foot of the bed. There was a schizoid scatter of pictures and drawings pinned to the wall, blackened and curled. The residue of a mind gone to batshit. He snapped a photo. He then studied the floor around the bed . . .

“Point your hose away,” growled Malort. “I’m gonna check somethin’.”

He stomped toward the shack, kicked over the burned-out bed frame, and yanked away a waterlogged rug underneath. There it was: a hatch that opened with a metal ring.

“Huh,” said the kid as Malort yanked the hatch open. “They got a basement?”

“They’ve got a tunnel and a bomb shelter. Follow it back a hundred yards or so and you’ll wind up under that house behind the fence. It turned out my intruder didn’t vanish; they slipped into a bedroom closet, climbed down a ladder, ran over, popped out here.”

Then, thought Malort, they’d rigged it so he’d get a face full of propane tank shrapnel if he tried to follow.

The kid looked amazed. “Damn. Is this like a cartel operation? I have a buddy who said they busted a place that had tunnels running all through the neighborhood—”

“Sir!” shouted a new voice from behind the kid. “What’s your business here?”

It was the older guy, coming to assert his authority. Malort tensed up. The dude was in his fifties or sixties, but that only put him in the same range as himself. And you generally didn’t want to tangle with a firefighter; they had muscles from hauling gear and bad attitudes from breathing toxic chemicals and remembering the screams of burning children.

“He’s looking for a big box,” said the kid. “He says the old guy who owns this land is dead over in that house behind the fence. And now he’s found a secret tunnel under the Unabomber hut. And the house is radioactive, maybe.”

“Who are you?” asked the older man, ignoring the kid completely.

Malort put his phone away. “I was just leaving.”

“No, you’re not. I’m gonna need to see ID. Hey!”

Malort ignored him and made his way back to the Buick. The senior fireman was talking into a radio now, hurrying to get himself between Malort and his car.

“You just wait right here.”

He put a hand on Malort’s chest. Malort stopped, looked slowly down at the gloved hand, then back up to meet the old dude’s eyes. There he detected the same apprehension he’d seen on the faces of authority figures since his growth spurt in middle school. He decided that, if things continued to progress in this fashion, he would open with forearm blows to the head and then delegate the closing argument to his boots. No doubt the other firemen would try to jump in, but you can’t waste your life worrying about stuff that’s not gonna happen until thirty seconds from now.

“Everybody,” announced Malort, “get out your phones and start recording, because if this old fuck doesn’t get out of my way, what happens next should really be something to see.”

He balled his fists, and his heart revved into another gear. As stimulants go, an early-morning ass-kicking was only a notch below speed. The old man gave him a perfunctory hard look and then backed down, allowing Malort to get behind the wheel of the Grand National unimpeded. The old man made a big show of photographing the license plate to save face.

As Malort backed up, he leaned out his window and said, “Never challenge a man in a Buick. He’s got nothin’ to lose.”

As he headed back to the main road, he pulled up the pic of the shack’s interior and zoomed in on the charred paranoia collage. Written on a handmade banner above the darkened scraps were three words:

THE FORBIDDEN NUMBERS

2

ABBOTT

The short trip to Abbott’s home afforded him just enough time to engage in his favorite pastime, which was carefully tabulating all of the ways in which the universe was wronging him in that particular moment:

1. His new passenger did, in fact, insist on sitting in the front, undeterred by the pile of objects he kept in that seat specifically to prevent that. She had just climbed right in and pushed aside his carefully arranged barrier of lip balm, asthma inhaler, vape pen, throat lozenges, antacids, and bag of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos, the woman blundering into his private world like a wet dog rolling onto a chessboard in mid-match.

2. She kind of smelled bad. She stank of smoke, but not cigarette smoke—it was the acrid stink of plastic and other materials that only burned when things went badly wrong. He didn’t know what exactly could go wrong with a human metabolism to make a person smell like that and didn’t want to know.

3. And this was the worst of all—she simply wasn’t upset enough. As soon as they were in the vehicle and rolling, her teary panic evaporated, and out from behind that cloud beamed horrible, horrible sunlight. It’s not that Abbott was opposed to others being happy (though he found the miserable were generally less exhausting to be around), but Abbott himself was definitely not happy, and in the aftermath of any transaction, this kind of mismatch in demeanor generally implied that one party had gotten screwed.

“I haven’t been on a road trip in forever,” she cooed, gazing at the passing megachurch and Chevy dealership like she was taking in the Jungle Cruise at Disney World. “I’m so excited! Do you realize that only seventy years ago, there wouldn’t have even been a highway from here to DC? You’d literally have been getting off on little country roads, some of them gravel, to get from one end of the USA to the other. If you go back, like, three lifetimes, it’s a trip you wouldn’t expect everyone to survive; somebody in the party would be dead of tuberculosis or bear attack before you got halfway. There are so many parts of the world where they still don’t have this, a wide, perfectly smooth road from basically anywhere to anywhere.”

“Yeah,” muttered Abbott as they stopped at a red light. He immediately took the opportunity to act like he was engrossed by something on his phone.

She glanced over and said, “Hey, have you ever noticed that when you’re watching a movie or reading a book and a character mentions social media, it makes you cringe? Like if a character says, ‘We’re blowing up on Twitter!’ or ‘We’ve gone viral on TikTok!’ it’s just really off-putting. Corny.”

“Oh, really?” mumbled Abbott, wondering if this woman was going to stop talking long enough to let him think.

“You know why I think that is? I think we hate being reminded that this is how we spend all our free time. We want our fictional characters to go out and do things in the real world. If they show the protagonist zoning out on the sofa with their phone, it’s always portrayed as pathetic, like, ‘Look at this poor sap.’ That’s weird, right, considering that’s probably the exact position we’re in when watching them do it?”

Abbott cleared his throat and said, “Hey, uh, when I get to the house, I’ll have to talk to my dad. This is his car, and I’m just letting you know right now that he—”

“Let me stop you right there. Remember, I can read your mind. You’re already planning how you’re going to use ‘My dad won’t let me go’ as a way to get out of the trip. Maybe you’ll say he won’t let you have the car, even though you’ve clearly already gotten permission to use it for work, and this is work. I bet you find yourself doing that a lot.”

“Doing what?”

“Instead of just saying what you’d prefer, you off-load the choice to someone or something else. Instead of ‘I don’t want to hang out with you,’ it’s ‘I have work that night’ or ‘I’m not feeling well.’ Nothing is ever expressed as your own needs and wants, so you never have to defend your choices or own the consequences later. I used to do it all the time.”

“Fine, I don’t want to take you on this trip.”

“Yes, you do! Are you honestly telling me the version of you a month or a year or ten years from now won’t be happy that you rescued a desperate person, went on an adventure, and got a couple hundred grand to jump-start your adult life? Sure, you don’t want to do the work right now, during the hard part. Nobody does! But the real ‘you’ doesn’t exist in the moment; you exist in the long term. That you, the whole you, will be glad you did this.”

“I don’t want to do it, because what you’re asking me to do is objectively crazy and certain to end in tragedy.”

“I bet you do that a lot, too. Catastrophize. Everything outside your comfort zone is a worst-case scenario waiting to happen. The reality is this: Somebody with lots of money needs a job done, and you were in the right place at the right time—nothing crazier than that. And in a week or so, it’ll be completely behind you; all you’ll have is the money, some cool memories, and a few thousand more miles on your old man’s car. Even that will be good for it. City driving is torture for cars; they need to get out and run! By the way, you’ve never asked my name, and we’ve reached the point where it’s going to be too awkward for you to ask and you’ll have to play some roundabout game to get me to say it. Let me save you from that: It’s Ether. E-T-H-E-R.”

“Do you have a last name?”

“Nope. Just Ether.”

“Okay, I’m starting to think this is a prank.”

“And what’s your name?”

“It, uh, would have shown on the app when you ordered the ride.”

“Yeah, but for all I know, you have a cool nickname you prefer to be called, like ‘Dutch’ or ‘Poncho’ or ‘Killer’ or ‘Professor BigNutz.’”

“Abbott is fine.”

“Good to meet you, Abbott. Remember, when we get to your place, it’s in and out, real quick. Right?” She shot a nervous glance into the rearview mirror and then tried to play it off by saying, “Ugh, I’ve gotta remove this lipstick. I look like the Joker, one of the versions that does a sloppy job with the makeup to let you know their movie is for grown-ups.”

She took off the WELCOME TO THE SHITSHOW hat and ran a hand through her razed hair, like she’d never felt it before. Abbott decided then that she had, in fact, cut her hair that very morning, maybe minutes before they’d met. That, oddly enough, was what caused him to silently add one more item to his packing list.

He spent the twenty-minute drive home silently rehearsing every possible disaster that could occur in the course of this trip—which, it turned out, wasn’t enough time to even scratch the surface of all his vividly dire scenarios.

“Nice house!” exclaimed Ether at the sight of Abbott’s dad’s McMansion, the exterior of which Abbott had always thought looked like stucco that the crew had drunkenly mixed with piss. “We’re close to the lake, right? Do you ever go? Ride a Jet Ski around, all that?”

“No. Dad goes out there and fishes.”

“Do you ever go with him?”

“If he ever offered that, I’d assume his plan was to drown me. I’ll be right back.”

He took the Navigator’s key fob inside with him, along with the two bundles of cash. He figured it was possible Ether could still hot-wire the vehicle and take off with it, but so what? He’d have a free hundred grand, and the stolen Navigator would be his dad’s problem.

The house was empty; Abbott had known his father wouldn’t be home, as the man worked six and a half days a week. He went to his own bedroom and packed ten days’ worth of T-shirts and cargo shorts, adhering to his habit of including far more pairs of underwear than he’d need as if he were going to just be continually soiling himself amid a nationwide shortage of pairs for purchase. He packed his eye drops, anti-dandruff shampoo, athlete’s foot spray, fingernail clippers, sleep mask, two types of skin ointment, hemorrhoid cream, and three different kinds of antacids. He went to his medicine cabinet for both of his prescriptions and noticed that one of them—the most important—only had two pills rattling around in the bottle. He felt a little jolt of panic and made a mental note to refill it before leaving town. He almost packed the white noise machine he needed for sleep but was pretty sure there were phone apps that did the same thing. He’d have to remember to download one, lest he be left alone in the dark with his slithering thoughts. He considered grabbing a second pair of shoes and decided he was being ridiculous.

He went to pack up his laptop, which was still on the little folding table positioned in front of the section of wall he’d painted bright green. Then he reconsidered and took a seat in front of the laptop and logged on.

“Uh, hey, gang,” he said into the laptop’s camera while stuffing items into his bag. “It’s Abaddon, something came up, so, uh, no streams this week and probably next. I have to hit the road. I’ll be checking in with you when I get the chance. Thanks for all your support, I’ll be back on by Monday the eleventh, I think. You guys enjoy your Fourth of July and your long weekend if, uh, you’ve got a job that even gives you days off. As I was packing, I remembered I have to get my brain pills refilled and realized how ironic it is that they’re for my anxiety, but nothing gives me anxiety like the prospect of running out. Or maybe that’s not ironic—does anybody know what that word even means? Anyway, I’m in the process of packing and imagining myself going into withdrawal while flying down the interstate at eighty miles an hour—”

He was interrupted by two brief beeps of the Navigator’s horn outside.

“Ha, uh, I guess she’s getting impatient. Alright, I have to go, if you don’t ever hear from me again, it means I’ve been murdered and dumped in a ditch somewhere. Bye-bye.”

He closed the laptop and wrapped the charging cable around it, having no idea that he’d just recorded what would become by far the most-viewed stream of his lifetime. The question now was what exactly to tell his dad. He could send a text, but that would simply yield a return call and, eventually, his father chasing him down to put a stop to the whole thing. No, he needed to be long gone before his dad even knew about the trip. After Abbott returned with enough money to spring himself from this prison, it wouldn’t matter. Hell, he could drop the Navigator off while his father was out on a jobsite and simply never have to talk to the man again. The sheer thought of it sent a flash of warm, golden light through his system, the sensation that he believed other people called hope.

He found a pen and a full-size sheet of paper that wouldn’t be easily overlooked and wrote,

Got offered a cash jobLast minuteNeed to help a friend move some stuffTaking the navigatorBack within 10 days probably—Abbott

He then pulled out one of the wads of cash and peeled off five hundred-dollar bills, placing them on top of the note and weighing both down with a brushed-steel saltshaker—an electric one that ground the salt for some fucking reason. He didn’t even know why he was leaving the money. Maybe he just wanted to prove that the job was real. That’s how it worked with his dad: Nothing was real until there was money to show for it.

Abbott then went up to his father’s bedroom for the last item he’d added to his packing list. He opened the bottom drawer of the nightstand and grabbed the box that contained his father’s handgun. Inside, the automatic was nestled in black foam, a spare magazine resting alongside it. Abbott only hesitated for a moment before taking the gun and returning the closed box to the drawer. There was no reason for his father to even notice it was gone. If an intruder happened to break in during Abbott’s trip, well, tough luck. Dad would have to go for the golf clubs in the closet.

He stuffed the gun under the clothes in his duffel bag, having no way of knowing that the charred remains of the bag and its contents—including that gun—would be examined by a forensics team less than five days later. He gathered everything and headed downstairs. He paused at the front door to take a look around the living room, wondering if he would ever set foot in this house again. He decided that from here on out, that would be the goal that kept him going, making sure he’d never have to.

“You came back! And you packed!” Ether giggled and clapped like a little girl as he approached. “I was sure you were gonna ghost me. You know how I thought you’d do it? I thought you’d go inside and call a friend who needs the money. Then you’d just hide in there until they pulled up, like, ‘Hey, Abbott told me you need a driver?’ There’d have been no reason for me to not just go with them instead.”

Abbott stopped and realized that would, in fact, have been a perfect way to get out of this. Was it too late to try? Ah, who was he kidding, he had nobody to hand the job off to.

Ether noticed what he was carrying, and her eyes narrowed. “Oh, your laptop. Uh, there’s something else we need to talk about. You have to leave that behind. And your phone, too.”

Ah, okay, thought Abbott. So this wasn’t happening after all. He felt a weight roll off him, the exquisite relief of canceled plans that extroverts will never know.

“I know you think this is a deal-breaker,” said Ether before Abbott could voice mostly those exact words. “But I’ve already ditched my phone. We can’t have any device that can be tracked. I’ll even disable the GPS in the car. We’ll have to navigate the old-fashioned way, with a map. And we’ll be cash-only, no credit cards.”

“Because the cops are after you.”

“No. The police don’t know about this, and there’s no reason for them to care even if they did. But there are people who want that.” She pointed to the back, where the box sat ominously.

“Your trunk full of heroin, you mean.”

“The box does not contain heroin or any other kind of drug. I promise. But even if it did, you’re not a conspirator; you’d be no more responsible than a cabdriver whose fare had a bag of coke in their suitcase. But no phones—that was a requirement from my employer.”

“It doesn’t matter. I can’t do this without my phone.”

“Those things didn’t even exist fifteen years ago! I bet you’re having a physical reaction right now at the thought of being untethered from it. Look at how well they’ve trained us! Constant sharing, constant tracking, everything offered up for scrutiny. See, that’s the one thing the system can’t tolerate today: privacy. In private, dangerous ideas happen, unique individuals are formed, cool secret boxes are moved. They can’t have that, can they?!?”

Ether was getting worked up, and Abbott got the distinct impression that, if allowed, she would continue on an uninterrupted rant on the subject for the next fifteen hours or so. Jesus, this woman’s red flags could supply a Communist parade.

“Okay,” she said, calming herself. “I can see you’re reacting like what I just said is crazy, that I must be some kind of fringe anti-technology weirdo, so just forget I said all that. I’m not the Unabomber.”

“The what?”

“The Unabomber? Real name Ted Kaczynski? The math genius who went to go live in a cabin in the woods in 1978, wrote an anti-technology manifesto, and then spent the next couple decades blowing up people with mail bombs? It doesn’t matter. What I want you to do is turn off your catastrophe reflex and think it through. For any nontrivial task you use that phone for, we can find a work-around. Trust me, I’ve been doing it for the last two years. Now please, please, can you take your gadgets inside so we can get moving?”

“So the other people who want that box, who are definitely not the cops, they have the power to track our devices?”

“I don’t know, but I can tell you from experience that it doesn’t take a cop or a super-hacker to track somebody. Anyone can do it, using software they can get for free. Stalkers do it all the time. Now come on, we have to go.”

He stared her down for just a moment but sensed her distress bubbling back to the surface and, for the second time, allowed it to sway him. He went back in and took the devices to his room, feeling naked without them as he reached the front door and again wondered if this would be the last time he’d see that living room or if he’d just see it again one minute from now after it turned out he needed to come back and do a third thing.

“Can’t you feel it?” asked Ether as he buckled into the Navigator. “The call to adventure?”

“No.”

“That’s so sad! What has the world done to kill our sense of wonder? This, right here, what you’re about to do, this is every downtrodden schlub’s dream come true. Every fantasy blockbuster has the same premise: A reluctant nobody is finally put into a position where he or she has to go on an adventure. Luke’s aunt and uncle are dead, Harry Potter’s homelife is a shit sandwich, Neo’s job sucks, Bruce Wayne’s parents got eaten by bats. The dream isn’t that the chance for adventure will come along—you can do an adventure any time you want—but that circumstances will line up just right so that you simply have no more excuses. Now here it is! That’s your ring back there, and the realm needs you to drive it to Mordor!”

She gestured to the box behind her, not knowing that a blackened remnant of one of its metal corners would later be recovered from the rubble and sold at a true-crime-memorabilia auction for $625.

“There’s a knot in my guts,” replied Abbott, “but it isn’t the thrill of adventure, it’s my self-preservation instincts telling me to turn back.”

“No, you’ve got it backward,” she said as they pulled into traffic. “Are you honestly telling me you’re not bored? Like, every day? Your phone can numb the feeling moment-to-moment, but it’s still there in the long term, the boredom. Well, that sensation exists for a reason! It’s your instincts telling you to go exploring. That boredom is your call to adventure.” She swept her hand across the windshield. “We have the whole country in front of us! The greatest and wealthiest and most dazzling empire that has ever existed!”

“Uh-huh,” muttered Abbott. “Ah, I need to swing by Walgreens first.”

Twitch chat logs from the stream posted at 8:04 A.M.,Thursday, June 30, by user Abaddon6969:

SteveReborn: My laptop fan is making a noise like it’s haunted.

DeathNugget: Good luck abs! Enjoy your trip!

Tremors3: Now what am I supposed to do on my holiday weekend, talk to my family?

SteveReborn: Is there a way to tell if your laptop is getting too hot?

SkipTutorial: I’m doing a poll, if you were stranded on a desert island with a bunch of people with no food and you had to resort to cannibalism to survive, who should be eaten first: An old man, or a baby?

DeathNugget: Crack an egg on it, see if it cooks.

Tremors3: Wouldn’t you get way more calories off the old man?

SkipTutorial: But he might have knowledge that would help you, maybe he’s an old seaman.

ZekeArt: Is it just me or did abs seem stressed?

DeathNugget: Got indigestion from all that chicken. Some of it even made it into his mouth.

SteveReborn: Maybe a family member got sick.

Covis: What sex is the baby?

SkipTutorial: I’m afraid to ask why that matters.

ZekeArt: I went back and watched the clip, the way he was acting. I don’t know, guys. This feels ominous to me.

DeathNugget: Everything feels like that to me, all the time.

CathyCathyCathy: Why would you have to eat a whole person, why couldn’t you go around and have people cut off bits of themselves to make stew?

DeathNugget: You’d have a whole island full of people limping around, sepsis spoiling their meat.

SteveReborn: Will an overheated laptop on your lap lower your sperm count?

Tremors3: God I hope so.

KEY

Retired FBI agent Joan Key wondered if she’d finally made enough small talk to get to her actual point. She’d been sipping diner coffee for the last fifteen minutes and could already feel it activating her reflux. The square-torsoed man in the suit across from her was droning on about his son’s soccer team and steadfastly avoiding any bureau talk, either out of concern that she missed it too much or that she didn’t miss it enough.

“. . . So now we’re in these last couple of months of high school, and I’m wondering, did he have any kind of normal experience there? It’s so different from when I was a kid. Did I tell you that he doesn’t even drive? He never got a license, he has no interest in it. When I was his age, I was obsessed with cars. So now he’s about to go off to college, and I think he’s emotionally about thirteen years old.”

The speaker was Patrick Diaz, a boxy LEGO figure of a man who had probably looked like an FBI agent in his mother’s ultrasound. Joan, whom everybody just called “Key,” had crashed his solitary breakfast at a Riverside diner, and Patrick had foolishly assumed she’d just wanted to catch up.

“That’s crazy,” said Key, which she hoped was sufficient to convince Patrick she’d been listening. “So, do you remember when that little bit of plutonium and cesium was stolen out of that DoE van at a San Antonio hotel in 2017 and never recovered?”

Patrick, who had been systematically working his way counterclockwise around a plate of eggs, sausages, and hash browns, dropped his fork and gave her a look he usually reserved for interrogations.

“You didn’t make it six months? I told you to get a hobby. Go talk to Hershel; he took up photography. He takes pictures of barns, travels the country. He does exhibits. You two can travel the countryside, get into trouble, have sex. I’ve been in locker rooms with the guy; he packs serious heat.”

“You do remember it, right? I mean the thing I was talking about, not whatever you just said.”

“Do I remember a bunch of alarmist headlines generated by a trivial amount of nuclear material getting stolen, the capsules geologists use to calibrate their tools? Are you actually asking if I remember, or is this just a preamble to the conversation you really wanted to have? And here I thought you actually missed me.”

“And do you remember,” said Key, persevering through Patrick’s tone, “how there’s a theory that the theft was connected to a chain of similar incidents, including a quantity of iridium-192 that went missing from a Strasburg, Ohio, warehouse a couple of years back? Again, a trivial amount, but if it turned out the same party was dedicated to collecting all of these trivial amounts on the black market, then mathematically, they would end up with a nontrivial amount.”

“Yes, in the sense that it’s technically possible that every stereo stolen from a vehicle in the last ten years is secretly being assembled into a gigantic sonic weapon that, when activated, will cause everyone on earth to simultaneously shit themselves.”

“So, there’s this thing I’ve been chasing down in my spare time, and my gut is telling me that it’s either a nothingburger or an all-hands-on-deck crisis and absolutely nothing in between. But if it’s going to happen, it’s going to happen soon.”

“How is your health these days?” asked Patrick, who had resumed eating in a particularly infuriating manner. “If you’re about to tell me I’m changing the subject, I seem to remember that the stress of the job ruined your ability to digest food. I remember sitting in a bar while you asked me how to identify dried blood in your stool. Then you got out your phone and showed me a picture of your bowel movement. I was eating a bowl of chili at the time, and you noted the similarity.”

“The job was stressful because of stonewall conversations like this. What if I’m onto something? What if there’s an incident and it comes out later that we failed to connect the dots? You won’t even let me tell you what it is!”

“Joan, everyone who has ever pursued law enforcement as a career, at any level, has had but one dream: to one day conduct a rogue off-duty investigation, finally shooting the bad guy off a tall building, causing him to fall until he impacts the windshield of a parked car below. But that doesn’t happen in real life, and frankly, this only tells me that you got out just in time.”

“Then this is your chance to talk me out of it. But you can only do that if you let me tell you what I know.”

“You think somebody is intending to do what, exactly? Make a dirty bomb and use it on the Fourth?”

A “dirty bomb” was a bomb that used nuclear material but not a nuclear bomb—it was just a conventional bomb designed to disperse radioactive shrapnel. The good news was that it did far less damage than a nuke, the bad news was that it would still be a nightmare, and any idiot could make one if he had access to the components.

“Just listen. Can you do that? Okay, while I’m talking, I want you to imagine one of those big corkboards with the photos connected by pieces of red yarn.”

“The kind you only find in the filthy homes of crazy people.”

“Eat your food so you’re not tempted to talk. Look, there’s this guy I’ve been watching for a while; he’s a conspiracy nut named Phil Greene. He lives in the middle of nowhere out in Apple Valley, in a house surrounded by a solid metal fence topped with barbed wire. He had a blog about the collapse of civilization—you know, the usual. So, on his property is a separate little loner shack where somebody else has been living, like there’s a partner he’s brought in, a fellow crazy. I don’t know who they are; it appeared to be a woman.”

“‘Appeared’ to be a woman. As in, that’s what you saw when viewing them through binoculars from behind the bushes?”

This was exactly how Key had spotted her, but she didn’t see how that was relevant. “A few hours ago, that little shack burned down. An examination of the aftermath revealed a wall full of conspiracy nonsense about a sentient AI that’s brainwashing humanity into extinction, that sort of thing. Then a mysterious stranger covered in tattoos showed up and inquired about a large box that had been transported from the scene, presumably by the mystery woman, the guy heavily implying that the contents were dangerous and important. And get this: It turns out there was a tunnel connecting the shack to the house with a bomb shelter in between. Then, a search of Phil Greene’s home revealed that the man himself was dead on his floor. A lot of his face was missing, like it had been eaten away.”

That got Patrick’s attention. “Eaten away by what? Chemicals?”

“Don’t know yet. This is all secondhand information; I of course did not have access to the scene, as I am merely a former federal agent who has spent the last six months getting high and watching road rage compilations on YouTube.”

“And you think that box that was transported from the scene contained, what? Some kind of improvised weapon of mass destruction? Did the locals turn it over to JTTF?”

That was the Joint Terrorism Task Force, a program created so that local police wouldn’t feel left out of FBI counterterrorism operations, despite often having minimal experience with the subject.

“No idea. Again, Patrick, why would they tell me? But I did hear that Greene had radiation warning signs all over his house. As for the mysterious female occupant, it’s believed she left the scene in Greene’s blue 1994 Ford Ranger pickup. The vehicle was missing from his home and has not, to my knowledge, been recovered.”

“So who’s the man with the tats who showed up asking about all this?”

“Somebody we definitely want to find and talk to. But he wanted that box very badly, to the point he presumably killed a man to get it.”