0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

Fraley's dear mother has just dies and left Fraley utterly alone in a hostile world. She sets off on a dangerous adventure, unsure of what lies ahead. Her only comforts are the faith her mother shared with her and the family Bible.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

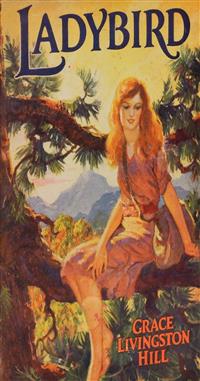

Ladybird

by Grace Livingston Hill

First published in 1930

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Chapter 1

Early 1920s

Fraley MacPherson stood in the open door of the cabin, looking out across the mountains. The peace of the morning was shining on them, and the world looked clean and newly made after the storm of the night before. She gave a little wistful sigh, her heart swelling with longing and joy in the beauty and a wish that life were all like that beauty spread out so wondrously before her.

For a moment, she reveled in the spring tints of the foliage—the tender buds of the trees like dots of coral over their tops, the pale green of the little new leaves, the deep darkness of the stalwart pines that seemed like great plumy backgrounds for the more delicate tracery of the other trees that were getting their new season’s foliage. Her glance swept every familiar point in the landscape, from the dim purple mountains in the distance, as far as the eye could reach, with the highlight of snow on the peaks, to the nearer ones, gaunt with rocks or furred with the tender green of the trees; then down to the foothills and the valley below.

There was one place, off to the right, where her eyes never lingered. It was the way to the settlement, miles beyond, the trail that led past a sheer precipice where her father had fallen to his death five months before. She always had to suppress a little shudder as she glanced past the ominous, yawning cavern that crept, it seemed to her sensitive gaze, nearer and nearer to the trail each month. It was the one spot in all the glorious panorama that spoiled the picture if she let herself see it, not only because of that terrible memory but also because it was the way the men of the household came and went to and from the far-off world.

Peace and contentment came into Fraley’s life only when the men of the household were gone somewhere into the world. Peace and contentment fled when they returned; terror and dismay remained.

The girl was good to look upon as she stood in the doorway, the sunshine on her golden hair that curled into a thousand ripples and caught the gleams of light until she looked like a piece of the morning herself.

Her eyes were bits of the sky, and the soft flush that came and went in her cheeks was like a wild mountain flower. She looked like a young flower herself as she stood there in her little faded shapeless frock, one bare foot poised on the toe behind the other bare heel—pretty feet, never cramped by shoes that were too tight for her, seldom covered by any shoe at all.

Her arms were round and smooth and white, one raised and resting against the door frame. The whole graceful little wild sweet figure, drenched with the morning and gazing into life, a fit subject for some great artist’s brush.

Something of all this came into the weary mind of the dying woman who lay on the cot across the room and watched her, and a weak tear trickled down her pallid cheek.

Fraley’s eyes were resting on a soft cloud now that nested in the hollow of a mountain just below its peak. She had eyes that could see heavenly things in clouds, and she loved to watch them as they trailed a glorious panorama among the peaks and decked themselves in the colors of the morning, or the blaze of white noon, or the vivid glory of the sunset. This cloud she was watching now had wreathed itself about until she saw in it a lovely mother, holding a little child in her arms. She smiled dreamily as the cloud mother smiled down at the little sleeping babe in her arms that, even as she watched, sank back into sleep and became a soft billow of white upon the mountain. How the mother looked down and loved it, the little billow of cloud baby in her arms!

“Fraley.”

The voice was very weak, but the girl, anxious, startled, her smile fading quickly into alarm, turned with a start back to the sordid room and life with its steadily advancing sorrow that had been drawing nearer every hour now for tortuous days.

“Fraley.”

The girl was at her mother’s side in an instant, kneeling beside the crude cot.

“Yes, Mother?” There was pain in her voice and a forced cheer. “You want some fresh water?”

“No, dear! Sit down close—I must tell you something—”

“Oh, don’t talk, Mother!” protested the girl anxiously. “It always makes you cough so.”

“I must—Fraley—the time is going fast now. It’s almost run out.”

“Oh, don’t, Mother! You were better last night. You haven’t coughed so much this morning. I asked that strange man last night to get word to a doctor. He promised. Maybe he will come before night!”

“No, Fraley child! It’s too late! No doctor can cure me. Listen, child. Don’t let’s waste words. Every minute is precious. I must tell you something. I ought to have told you before. Come close. I can’t speak so loud.”

The girl stayed her tears and leaned close to the beloved lips, a wild fear growing in her eyes. Persistently she had tried to hide from herself the fact that this beloved mother, her only beloved in all the world, was going from her, tried not to think what her lot would be when she was gone.

Persistently now she put the thought from her and tried bravely to listen.

“Fraley, when I’m gone you can’t stay here.”

Fraley nodded, as if that had long been a settled fact between them.

“I hoped. I hoped. I always hoped I’d get strength to go with you and get away somehow only I never did. I never found a way nor money enough for us both even for one ”

“Don’t, Mother!” moaned the girl with a little quick catch in her breath. “Don’tapologize. As if I didn’t know what you’ve been through. Just tell me what you want me to know, and don’t bother with the rest. Iunderstand.”

The feeble hand pressed the girl’s strong one, and the pale lips tried to smile.

“Dear child!” she murmured then struggled through a spell of coughing, lay panting a moment, and struggled on. “There isn’t enough yet not even for you,” she panted.

“I don’t need money,” scorned the young voice. “I can take care of myself.”

“Oh, my dear!” sighed the woman and then girded herself to go on.

“There’s only fifteen dollars. It’s in three little gold fives. Never mind how I got it. I sold the heifer they thought went astray to that stranger that rode up here two months ago. I had to bear a beating, but it gave me the last five. The first I brought out here to the wilderness with me, and the second I got from the man who came here the day your father was killed. I sold my wedding ring to him but that was all he would give ”

“Oh, Mother! You oughtn’t to talk,” pleaded the girl, as the mother struggled with another fit of coughing.

“I must, dear! Don’t hinder now the time is so short!”

“Then tell it quick, Mother, and let’s be over with it,” cried the girl, lifting the sick woman’s head tenderly and helping her to sip a little water from a tin cup that stood on a bench by the cot.

“It’s here”—she pressed her hand over her heart—“sewed in the cloth. You must rip it out. Put it in the little clean bag I made for it, and tie it around your waist. If Brand Carter should lay his hands on it once, you’d never see it again! Twice he’s tried to see if I had anything, once when he thought I was asleep. He suspected, I think. Take it now, Fraley, and fix it out of sight around your waist. Here, take the knife and rip the stitches quick. You can’t always tell if one of the men might come back! Go look down the mountain before you begin. Hurry!”

In a panic, the girl sprang to the door and gazed in the direction of the trail, but the morning simmered on in beauty, and not a human came in sight. A wild bird soared, smote the morning with his song smote her young heart with sorrow. Oh, why did that bird have to sing now?

She sprang back and deftly cut the stitches. Through blinding tears she sewed the coins into the bit of girdle her mother had crudely made from a cotton salt bag—most of their clothing was made from bags, flour and salt and sometimes cotton sugar bags—and solemnly girded herself with it as her mother bade her.

“Now, Fraley,” said the mother, when this was done to her satisfaction, “you’re to guard that night and day. It won’t be long till I’m gone. And you’re not to think you must spend any of it on me on burying or like that—”

A sob from Fraley stopped her, and she laid a wasted hand upon the bright, rough head that was buried in the flimsy bedcover.

“I know little girl—Mother’s little girl! That’s hard but that’s a command! Understand, Fraley? It’s Mother’s last wish!”

The girl choked out an assent.

“And you’re not to stay for anything like that. It wouldn’t be safe! Oh, I ought to have got you out of here long ago! Only I didn’t see the way clear. I couldn’t let you go without me. You were so young!”

“I know, Mother dear, I know!” sobbed the girl, trying to smile bravely through her tears. “I wouldn’t have gone, you know, not without you!”

“Well, I should have gone. We should have gone together long ago—found a nice place in the wilderness, if there wasn’t any other way—a place where they would never think to look—where we could die together. That would have been better than this than leaving youhere—all alone. You all alone!”

“Mother, don’t blame yourself! Please! I can’t bear it!”

A wild rabbit scurried across the silence in front of the cabin, and a hawk in the sky circled great shadows that moved over the spot of sunshine on the cabin floor. Fraley, with ears attuned to the slightest sound in her wide, silent world, sprang up and darted to the door to survey the wilderness then came back reassured.

“It’s no one,” she said, laying her firm young hand on the cold brow. “Now, Mother, can’t you rest a little? You’ve talked too much.”

“No, no,” protested the sick woman, “the time is going. I must finish! Fraley, go look behind the loose board under your bed. There’s a bag there. Bring it! I want to show you. Quick!”

Fraley came back with a bundle of gray woolen cloth, which she examined wonderingly.

“I made it from your father’s old coat,” explained the mother eagerly. “It’s some worn, and there’s a hole or two I had to darn, but it will be better than nothing.”

“But what is it for, Mother?” asked the girl, puzzled.

“It’s a traveling bag for you when you start. It’s all packed. See! I washed and mended your other things and made a little best dress for you out of my old black satin one that had been put away in the hole under the floor since before you were born. It may not be in fashion now but it’s the best I could do. I cut it out when you were asleep and sewed it while you gathered wood for the fire.”

“Oh, Mother!” burst forth the girl with uncontrollable tears, “I shan’t ever need a wedding dress. I don’twanta wedding dress. I hate men! I hate the sight of them all. My father never made you happy. All the men around here only curse and get drunk and swear. I shall never get married!”

“I’m sorry, dear child; you should never have known all—this—sin, this terror—Oh, I dreamed I’d get you out of this—into a clean world someday! But I’ve failed! There are good men—!”

Fraley set her lips but said nothing. She doubted that there were good men.

“Fraley, we must hurry! My strength is going fast.”

“Don’t talk, Mother! Please.”

“But I must! Look in the bag, child. I’ve put the old Book there. It’s almost worn out, but I’ve sewed it in a cloth cover. Fraley, you’ll stick to the old Book?”

“Yes, Mother, I promise. I’ll never let anybody take it from me!”

“But if it should be lost or stolen, Fraley, you’ve much of it in your heart. You’ll never forsake it, Fraley?”

“Never, Mother. I promise,” said the girl solemnly.

“Well, then I’m satisfied,” sighed the mother, closing her eyes. “Now, child, hide the bag again. Everything is there I could give you. Even your father’s picture and mine when we were married, and a few papers I’ve kept. Put them away, and come back. I want to tell you what I’ve never told you before.”

Fraley obeyed, trembling at what revelation might be coming.

“Come closer, child, I’m short of breath again. And I must tell—I should have told before!”

Fraley held her mother’s hand closer in sympathy.

“Child, I ran away from that home and got married. I’ve never seen nor heard from any of my own since…” There was a great sob like a gasp at the end of the words.

“Oh, Mother!” gasped the girl in wonder and sorrow. “Oh, Mother, if you’d only told me, I might have helped you more!”

“Fraley darling, you have been everything. You have been wonderful! You have been my world my life. Oh, if I could take you with me where I am going now. But you’ll come? You’ll be sure and come?”

“Yes, I’ll come! That will be everything for me, Mother.”

“But I must hurry on.”

“Mother, did you have”—the girl hesitated, almost shyly—“did you have a mother like you? You told me once my grandmother was dead. Was she dead when you went?”

“Yes, child. She had been gone a year. You think I would not have gone if she had been there? Well perhaps. I do not know. I was young and headstrong. Even before she went she warned me against Angus MacPherson. But I did not listen! Perhaps she worried herself into the grave about me. While she lived I did not go with him much. But she knew where my heart was turning. I was mad with impatience to be out like other girls.”

Fraley listened as to a fairy tale. Her mother, young and wild like that!

“Angus was young and handsome. He had dark curls and a cleft in his chin and he was very much in love with me then—No, child, you mustn’t look like that. You mustn’t think hard of him! He was all right always till he took to drink—”

“He didn’t have to drink, Mother,” said the fierce young voice. “He must have known what drink was.”

“Well child, it came little by little. You don’t understand. He never meant to be like that, not when he started. He was always wild and independent. He didn’t care what folks thought of him, but he wasn’t bad. Not bad! And when he came and told me he was in a hole someone had framed him up to a life in the penitentiary to cover a gang’s doings and that there wasn’t anything for him but to disappear forever I believed him. I believe him yet, Fraley! He didn’t do the robbing; he didn’t forge the check. There’s all the papers in the bag there to prove it. But he wouldn’t go back on one fellow who had been innocent. If he got free and told the truth the other boy would have to bear it and he had a sick old mother. He was like that, Fraley, your father was. He wouldn’t go back on someone who had been his friend.”

“But he went back on you!” said the fierce young voice again. “He brought you out away from everybody that loved you and then he treated you”—the girl’s voice broke in a sob of indignation.

“Not then, child,” pleaded the mother’s voice. “He was tender and loving, but he put it up to me! It was either go with him then or never see him again. Fraley, I loved him!”

“Don’t mind me, Mother,” said the girl, struggling for control of her feelings. She could remember the cruel blows he had given the frail mother. She could remember so many things!

“It was the drink that did it,” pleaded the mother, reading the thoughts of the sensitive girl and struggling for breath as a fit of coughing seized her.

Their old dog trotted in from his wanderings after the cow, snuffed around the cot lovingly, and lay down with a soft thud of his paws on the bare floor. Fraley put the tin cup of water to her mother’s lips again, and after a time she rallied.

“I must hurry!” she gasped as she lay back on the pillow. “I can’t stand many more like that!”

“I wish you wouldn’t,” begged the girl. “What difference will it make? I love you, anyway, and I don’t care anything about all the rest. It’s you you—I want. I can’t bear to see you suffer!”

“No, child”—the feeble hand lifted just the slightest in protest—“let me finish!”

Fraley’s answer was a soft hand on the thin gray hair around her mother’s temples.

“Go on, Mother dear,” she breathed softly.

“My father was a stern man, especially since my mother’s death—” The sick woman whispered the story with the greatest difficulty. “He had said—if I—married—Angus—I need never—come back.”

The old dog heaved a deep sigh as if he, too, were listening.

The sick woman paused for breath then went on, her words very low.

“That night I slipped out—of the house—when he—was asleep. We were married in a little out of the way church—I pasted the marriage certificate and license—into the Bible—You’ll find it—” She paused as if her task were almost done then hurried on. “When—we got out here—we found—this was a place of—outlaws.”

“Outlaws!” said Fraley, startled. “What does that mean?”

“It means—that every man for miles around—has committed some crime—and is afraid—to go back—where he—came from.”

Fraley turned her startled eyes toward the open door and her faraway mountains.

“Was—my—father—” she faltered at last.

“No! No! I told you he was innocent—”

“Why didn’t he get away then?”

“He couldn’t—child—even if he had had money—which he hadn’t—not a cent. The men here wouldn’t let him go. They would have shot us all first! Your father—knew too much. There were—too many—notorious criminals on this mountain. There—wouldn’t have been—a chance for the three of us—You see—we didn’t find it all out—not till after you came. You were five months old—the day—your father—told me.”

A chill hand seemed to be clutching the girl’s throat as she stared unseeingly at the spot of sunshine on the floor beside the old brown dog.

“We tried—to think of some way—but your father—knew too much. He’d been out with the other men—rustling cattle—He’d have been implicated with them in their crime—of course. At first he didn’t understand. At first he thought it was cattle that belonged to them. He was green, you know, and didn’t understand. The man who brought him out here had made great promises. He had expected to go back rich—someday. I had thought how proud I would be to show my father I had been right about Angus. I thought he would—be a—successful man and we would go home—rich!”

The old dog stirred and snapped at a bug that crept in the doorway, and the sick woman looked around with a start.

“It’s all right, Mother, no one is coming,” said the girl with a furtive look out the door.

The mother struggled on with her story. “When your father—found out, when he saw he, too, had been stealing, and there was no hope—to get away—it seemed he just gave up—and let go. He said we had to live—and there was no other—way. He had always been wild—you know—and it seemed as though—he kind of got used to things—and fitted right in with the others after a while. When I cried and blamed him—then he took to drinking hard—and after—that—he didn’t care, though sometimes he was—very fond—of you. But when he got liquor, then he didn’t care.”

“Drinking didn’t make it any better!” said the fierce young voice.

“No—it didn’t,” went on the dreary voice. ”No—and then he brought the men—here. I couldn’t help it—I tried. But I saw they had some kind—of a hold—on him. He was afraid!”

The dog made a quick dash out the door after a rabbit that had shot by, and the woman stopped and looked up sharply.

“Listen!” she said, gripping the firm young hand in an icy clasp. “I must say the rest quick!” She was half lifted from her pillow with her frightened eyes turned toward the door. “I might go—or they might come—any minute now. Listen! I had a brother. He went to New York. He was Robert Fraley. You must find him! He loved me. Angus had people, too, but they were ashamed of him. They were rich but it’s all written down. You must get out of here at once. Promise me! I can’t die till you promise.”

“I promise!”

“Promise you won’t wait, not even for any burying.”

“But, Mother!”

“No ‘but,’ Fraley! They’ll bury me deep all right, don’t worry. They’ll want me out of their sight and mind. Many’s the time I’ve told them about the wrath of God—Oh I know they’ve had me in their power since I was sick. I had to shut up. But when I’m gone they’ll take it out on you! Fraley, my girl, they can’t hurt my dead body. No matter what happens God will know how to find it again at the resurrection. But they can do terrible things to you, my baby! You’re safer dead than here alive, if it comes to that. Now promise me. Promise!”

Fraley choked back the racking sobs that came to her throat and promised. The woman sank back and closed her eyes. It seemed she hardly breathed. The girl thought she was asleep and kept quite still, but after a time the stillness frightened her, and she lifted her trembling hand and touched the cold cheek. Her mother opened her eyes.

“I’ve been praying,” she murmured. “I’ve put you in His care.”

There was a flicker of a smile on the tired lips, and the cold hand made a feeble attempt at a pressure on the warm, vivid one it held.

After that she seemed to sleep again.

The girl, worn with sorrow and apprehension, sank in her cramped position on the floor into a troubled sleep herself, and the old dog, padding softly back from the hunt with delicate tread, slunk silently down near her, closing sad eyes and sighing.

Tired out, the girl slept on, past the noon hour, into the afternoon, never knowing when the cold hand grew moist with death damp, never seeing the shadow that crept over the loved face, the faint breaths, slow and farther between, as the dying soul slipped nearer to the brink.

The dog, hungry, patient, sighed and sighed again, closed his eyes and waited, understanding perhaps what was passing in the old cabin, his dog heart aching with those he loved.

The shadows were changing on the mountaintops, and the long rays of the setting sun were flinging across the cabin floor, laying warm fingers on the old brown dog, bright fingers on the gold of the girl’s hair, and a glory of another world on the face of the passing soul. Suddenly the dying eyes opened, and with a gasp, the woman clutched at the young relaxed hand that lay in hers.

“Fraley! Child! The old Bible!” The words were almost inarticulate except to loving ears, but the girl started awake and put her warm young arms around her mother.

“Yes, Mother. I’ll keep it. I’ll always keep it! I’ll not forget. I’ll never let anyone take it from me.”

Her words seemed to pierce the dying ears, and a smile trembled feebly on the white lips. For a long moment she lay in Fraley’s young arms, as if content, like a nestling child. Then, with superhuman strength, the dying woman lifted herself, and a light broke into her face, a light that made her look young and glad and well again, as her child could never remember her having looked.

“He’s come for me!” she cried joyously, as if it were an honor she had not expected, and then, her eyes still looking up as if hearing a voice, said, “He’s going to keep you safe! Good-bye! Till you come!”

With the smile still on her lips, she was gone. The girl, stunned, dazed with her sorrow yet understanding that the great mystery of passing was over, laid her back on the flabby pillow and gazed on the face so changed, so rested in spite of its frailty, its wornness; that face already taking on itself the look of a closed and uninhabited dwelling. She watched the glory fade into stillness of death, wrote it down, as it were, in her secret heart, to recall all through her life, and then, as sometimes when she had watched the sunset dropping behind the mountain and all the world grow dark, she knew it was over, and she sank down on her knees beside all that remained that was dear to her in the great world and broke into heartbroken sobs.

The dog came and whined around her, nosing her face and licking her hands, but she did not feel him. Her heart seemed crushed within her. All that had passed between herself and her mother during that long, terrible, beautiful parting had faded for the time, and she was throbbing with one fearful thought. She was gone, gone, gone beyond recall! For the moment, there was no future, nothing to do but to lie broken and cry out her terrible pain. It seemed as though the pent-up torrent obliterated everything else.

Then, suddenly, a low, menacing growl beside her startled her back to the present. She lifted her face and turned quick frightened eyes toward the neglected watch she had been keeping, and her heart stood still. There in the door, silhouetted dark against the bloodred light of the setting sun, stood Brand Carter, her mother’s enemy and hers!

Chapter 2

It was incredible that a girl could have grown to Fraley’s years in this wilderness, this mountain fastness of wickedness, so fine and sweet and unsoiled as this girl was. Nobody but God would ever know at what expense to herself the mother had been able to guard her all her years, especially the last few months since her father died.

Like the matchless beauty of the little white flower that grows in the darkness of a coal pit and, protected by some miraculous quality with which its petals are endowed that will not retain the soil, lifts its starry whiteness amid the smut, so the child had grown into loveliness, unstained.

And now the frail hand that had shut her from the gaze of unholy eyes more times than she would ever know, the strong soul that in a weak body had protected her from dangers unspeakable, was gone; cold, silent, still, it could no more protect her. The time that her mother had warned her against had come and caught her unawares! She had been merely weeping! She sprang to her feet in a terror she had never felt before. There had been times in the past when she had been deathly frightened but never like this. Her very heart stood still and would not beat. Her breath hurt her in her lungs; her eyes seemed bursting as she gazed; her mind would not function. He had come. It was too late! It was useless to flee!

Then, with sudden realization, she glanced toward the silent form on the cot beside her with an instinct to protect her who could no longer protect herself. But the majesty in that dead face brought the realization that the dead need no protection. She caught her breath in one quick gasp and tried to think.

But even that glance had been enough to break the spell that rested on the room. The man’s eyes went to the dead face, too, and with an oath, he made a move to come forward.

The old dog gave a low growl and sprang with fangs exposed, but a cruel boot caught him midway and sent him sprawling outside the door, where for a second, he lay stunned by the well-aimed blow.

“Ugh! Croaked at last!” said the man, coming close to the cot, peering down at the dead face, lifting a waxen eyelid roughly, and glaring into the dead eye. “Well, she took long enough about it.”

Then he turned to the trembling girl, who, with enraged eyes, watched him.

“Now, young’un, you git out and milk the cow and git us a good supper. The men are coming, and we’re hungry. See? Now, git!”

He seized her in a rough grip and flung her through the door, almost into the arms of another man who had just sprung from his horse and was coming toward the cabin. He was a young man with an evil face and lustful eyes. Pierce, they called him, Pierce Boyden, lately come to the wilderness. Fraley hated him and feared him.

“Here, you Pierce, come in here! We gotta get rid of this old woman. Give us a hand.”

Then, turning to the other three men who drove up, he gave his orders.

“Pete, you stand there with your gun and watch that girl while she milks that cow and gits us some grub. Whist, you and Babe get your shovels and be quick about it.”

Fraley darted around the house to where the cow stood waiting to be milked. Every word that was spoken stung its terrible meaning into her frightened soul. Scarcely knowing what she did, she went at the task, a task from which her mother had saved her as long as she could. The angry voice of Brand rang from the house where he was moving around—roughly shoving a chair across the floor, flinging the old tin cup against the wall in his anger. She shuddered as she thought of what the men were doing. Her precious mother!

The tears that had been flowing seemed to sting backward in her eyes. Her cheeks scorched dry, her heart came choking to her throat. Her hands were numb and could scarcely hold the pail in place. The milk was going everywhere.

The voice of Brand, drunker than usual, sailed out into the twilight from the open doorway. “You, Pete! Stay there till I come back. If she starts to run, shoot her in the feet, then she can’t go fur!” He laughed a terrible haw, haw, and then she could hear the awful procession going down to the mountain.

She knew what they were doing. She could hear the ring of a shovel against a rock. It seemed that every clod they turned fell across her quivering heart.

Pete, with his gun, stood guard at the corner of the house. Pete, the silent one with the terrible leering eyes of hate. Pete who never smiled, not even when he was drunk. And now he was drunk! Oh, why had she lost her senses? Why had she not gone before they came, as her mother had meant her to do?

The old dog hobbled to her and began to lick the tears from her face, and she felt comforted and less afraid. She whispered to him to lie down, and he obeyed her, sneaking into a shadow behind the cow.

Pete stalked nearer and gruffly bade her to hurry. She managed to finish her milking, though her hands still felt more dead than alive, and stumbled into the house. The old dog slunk after her and hid in the bushes near the door. The shadows were growing long and deep on the grass and on the mountains across the dark valley where they had taken—No! It was not her mother! Merely the worn-out dress with which she was done! Hadn’t mother tried to make her understand that?

She tried to take a deep breath and hold her shoulders up as she marched around the room, tried not to see the empty space where the cot had stood. Tried not to think, tried just to get the supper and get the men to eating. They were hungry now, and they would not bother her until they were fed, if she fed them quickly.

She started the coffee boiling and put some salt meat on to cook. She fried a large skillet of potatoes and mixed up the crude corn bread. The familiar duties seemed to take her hours, and all the while her heart was listening in terror for the sound of returning feet. Pete had come into the house and was sitting in the corner with his gun aimed toward her. She shuddered when she looked at him, not so much because of the gun as because of the cunning look in his eyes, and once as she glanced up because she could not keep her eyes away from his shadowy corner he laughed, a horrid cackle, almost demonical. Pete, who never even smiled! It was as if he had her in his power. As if he was gloating over it. She would rather Brand had left almost any of the men than Pete. There was something about him that did not seem quite human.

Feverishly she worked, her head throbbing with her haste, setting out the old table with the tin plates, the cracked cups. She could hear the men’s voices. They were coming back up the mountain now. They were singing one of those terrible songs about hanging somebody by the roadside, the one that had always made her mother turn pale.

Fraley sprang to the stove and broke eggs into the hot fat beside the meat. She would give them such a supper as would make them forget her for the moment.

The corn bread was ready, smoking hot on the table as the men came noisily in. Brand watched her as he towered above the rest, his evil eyes gloating, she thought, with the same look that had been in Pete’s eyes. She brought the coffee pot and set the frying pan with its sizzling meat and eggs in the middle of the table, and the men, with drunken satisfaction, sat down and drew up their chairs. They were joking among themselves about their task just completed, in words that froze her heart with sorrow and horror. But she was glad to have their attention for the moment taken from herself.

They were all busy with the first mouthfuls now like hungry wolves, too busy to spring.

She turned stealthily, and her foot touched something. It was the old tin cup that Brand had kicked away in his anger. With quick instinct, she stooped and picked it up. She might need it. Some bits of dry bread that were on the shelf as she passed she swept into it, and hiding the cup in the scant gathers of her cotton dress, she made a stealthy movement toward the door of the room that had been her refuge from the terrors of the world ever since she could remember.

The men did not notice her. They were eating.

Silently, as unobtrusively as she could move, she glided to the door and slipped within. They had not seemed to notice she was gone. She pushed the bolt quickly. It was a large bolt, and her mother had kept it well oiled so that it would move quickly and silently if need be. There was a bar, too, that slipped across the bottom of the door. That, too, her mother had cunningly, crudely arranged. Probably it would not endure long in a united attack, but it was a brief hindrance, at least. It she only dared draw the old trunk across the door! But that would make a noise.

Stealthily, she moved in the dark little room that was scarcely larger than a closet. With fingers weak with fear, she lifted the loose board beneath the cot and pulled out the woolen bag. Suppressing the quick sob at the thought of her mother, she opened the flap of the bag and stowed away the tin cup and bread, then standing on tiptoe, she lifted the bag to the little high window over the bed and pushed it softly over the sill. As it fell she listened breathlessly. What if the men should hear it drop, or Larcha the old dog should begin to bark, and the men should go out to look around!

Softly, she took down the old coat that had hung on a peg in the wall ever since her father died and put it on. The men were talking loudly now. Two of them seemed to be fighting over something that a third had said. It would perhaps come to blows. It often did. She welcomed the noise. It would cover her going. But as she stepped upon her little bed, her heart suddenly froze in her breast! What was the terrible thing they were saying? It was about herself they were fighting. They were saying unspeakably awful things. For an instant, she seemed paralyzed and could not move. Then fear set her free, and she was stung into action. It was not an easy matter to climb from the creaky little cot to the high narrow windowsill above without making a particle of noise, and she was trembling in every nerve.

The window was barely large enough to let her slenderness through, and it required skill to swing outside, cling to the windowsill, and then drop with catlike softness to the ground, but it was not the first time she had accomplished it. There had been other times of stress in the little cabin when her mother had sent her away in a hurry to a refuge she had, out in the open, and that experience helped her now. But there was no time to pause and be cautious, for at any moment the men might discover her absence and call for her. Then they would rush outside to hunt her down, and death itself would be better than life!

With the awful words of the men ringing in her ears, she dropped from the window, praying that she might not make a false landing. Her head seemed dizzy, and there was a beating in her throat. For an instant her body felt too heavy to rise up, and she lay quite still where she had dropped, holding her breath and listening.

The old dog came softly, whining and licking her face as if he understood she was in trouble, and new panic seized her. She hushed him into quiet, picked up her bag, and slung it over her shoulder by its strap, then, her hand upon the dog’s head, she moved like a small shadow across the ground, her bare feet making no sound, her heart beating so wildly that it seemed as if it could be heard a mile away.

It was not toward the trail she directed her steps, and she did not look back to the awful pass where the precipice was, nor down the valley where they had carried her precious mother’s form. Into the wilderness where there was no trail, into the darkness, she went.

Like a voice, there silently stole into her heart a phrase from the words she had learned for her mother, sitting morning after morning in the cabin door in the sunshine, learning her lesson out of the old Book, the only book she had, or huddled in a blanket when the weather was cold and the fire was low, learning, learning, always learning beautiful words to repeat to her mother. It was the only school she had ever known, and she loved to study and to repeat the words she had learned, pleased to be able to say them perfectly, often asking what they meant but only half comprehending what her mother tried to tell her. Now suddenly it seemed that these words had taken on new, wide meaning.

“He knoweth the way that I take. He knoweth the way. He knoweth.”

As she stole along cautiously—her accustomed feet finding the pathway in the dark, her heart fearful, her eyes looking back in dread—the words began to come like an accompaniment to her silent going, and their meaning beat itself into her soul.

Suddenly, back through the clear stillness of the starlit night, came a sharp cracking sound, a snap and a sound of rending wood, then a kind of roar of evil bursting from the door of the cabin. Casting a frightened look back, she could see the light from the cabin door that was flung wide now, could hear the men’s voices calling her angrily, shouting, swearing a tumult of angry menace. It put new terror into her going, new tremblings into her limbs. She hastened her uncertain steps blindly on toward an old tree that had been her refuge before in times of alarm, her hands outstretched to feel for obstructions in her path as she fled down the side of the mountain.

She could hear the clatter of hoofs now, ringing out on the crisp night air, as the horses crossed the slab of rock that cropped out a little way from the house. Yes, some of them, at least, were coming this way. She had hoped they would search the trail first, but it seemed they were taking no chances. They would be upon her very soon, and her limbs were trembling until she felt they would crumple under her. Her feet were so uncertain as they stepped. Her heart was beating so that it seemed as if it would choke her. Weakly she snatched at a young sapling and swung herself up to a cleft place in a great rock she knew so well. If she could only make it now and reach the foot of the old tree!

Breathlessly on she climbed, not pausing now to look back, and at last she reached it.

As she swung herself up in the branches, she remembered the old dog who had followed her. Where was he? Had he gone back? Much as she loved him and wanted his company on her journey, she realized now that she should have shut him in the cow shed where he could not have followed her. Now, if he lingered at the foot of the rock, he would give away her hiding place to the enemy!

For an instant she paused, but the ring of horses’ hoofs on the rock-strewn path she had just left warned her that she had no time to spare. They were hot-foot on her track. Possibly it was Pete, and it might be he had searched out her haunt. Pete had a way of appearing at the shack of late when everybody thought he had gone afar. Pete might have seen her going to her tree.

The thought sent the blood hurrying through her veins with feverish rapidity. Her hands almost refused to hold on to the branches, so frightened was she. She tried to think if this tree was no longer a refuge, where could she go? It was too late to go back, to hope to get down this sheer rock on the other side and make the valley before she would be heard, even though the dark did hide her. It would be folly. She would be dashed to pieces in the dark, for the way down the precipitous incline was dangerous even in the daytime when one could pick and choose a cranny for a footing, step by step. It was a long and slow and fearsome descent. To make it in the dark, and in haste, would be impossible. To go back to where she had begun to descend to this rock would be to meet the enemy face-to-face. There was nothing for it but to climb to the topmost limbs and wait. Yet, if it was Pete and he should find her, he would not hesitate to cut down the tree! She would be at his mercy!

In terror she climbed to heights she had never ventured before until she clung at the very top of the great tree, enveloped in its resinous plumes. Even in the light of day it would have been hardly discoverable that the tree was inhabited, so thick were the branches. It had been Fraley’s playhouse in her childhood and her refuge in many a time of fear. But she had always guarded her goings so that she thought no one but her mother knew of her whereabouts. Now, however, in this, her most trying crisis, she began to wonder whether perhaps some of the men might not have spied upon her.

Clinging to the old pine, her arms around its rough trunk, her feet curled into the crotch of the slender branch upon which her weight rested, the woolen bag her mother had made dragging heavily from her shoulder, she waited, her heart beating wildly.

If it had been daytime, she could have almost looked into the eyes of her pursuer, though his horse’s feet traveled ground far above where the tree stood, for the treetop was almost on a level with him. But she could see nothing now but the black night ahead of her and a high line of dim starry sky far above the mountain. But she knew by the sound that her pursuers were almost opposite her and that a moment more would tell her whether they had discovered her trail, for now if they guessed where she was they would turn abruptly down the mountain toward her. And, oh, what had become of Larcha, the old dog? If he only would have sense enough not to whine!

Suddenly a sound broke on her startled ear, like the hurtling of some heavy object through small branches and dry sticks, a rush, a low menacing growl, followed by curses and the sound of a plunging horse, rearing and stumbling on the slippery hillside.

Instantly her forest-trained ears understood. It was almost as if she could see what was being enacted before her in the dark. Old Larcha, the dog, had tried to help. He had cunningly stolen above the trail where the enemy was coming and, at the right instant, had plunged down upon the horse and his rider, and had dared to attack in defense of the girl he loved, and had been intelligent enough to try to mislead her pursuer into making chase higher up the mountain, and so covering her hiding place.

Instantly she knew, now, even if she had not heard the rough curses, that it was Pete who rode that horse. Larcha had always shown deep dislike to him and fear in his presence. It had been a joke among the men to send Larcha to Pete and hear him growl. And Pete had been cruel to the dog, kicking him brutally whenever opportunity offered, throwing stones at him without provocation, pointing the gun at him. The dog would always hide when he came around. Fraley had often noticed how the hair would rise on the brown back and how the dog would lift his upper lip and show his teeth whenever the man came in sight. He would always disappear, hiding for hours together, until his enemy had left the place. Larcha had cause of his own, now, to fight her pursuer. Yet Fraley knew he would have done this even without the personal cause. Since she was a little child, Larcha had been her one playmate and comrade whenever she strayed away from her mother. Larcha was the only friend she had left in the world. And now that friend was offering up himself for her. For Fraley had little doubt what Pete would do to the dog. The answer to her fear came sharp and quick in a shot that rang out over the mountain, followed by the dull thud of a body falling on the ground and rolling a few paces.

Then into the night came the sound of curses and of other horses riding and cries.

A sharp little light shot out from the rider of the horse and twinkled over the ground until it focused on a dark, huddled object at the foot of a tree. Pete had recently come from a surreptitious visit to the outside world and had brought back with him a number of little flashlights. Yes, there was no question but that her pursuer was Pete and that, if he wanted to, he would shoot her as readily as he had shot Larcha. At least he would shoot to disable, perhaps not to kill.

The other horses were coming on, Brand’s big roan stumbling with his lame foot, and two others. They would surround her now. Oh, if she could only be sure they would kill her. The awful words she had heard the men speak a few moments before still rang, menacing, in her ears.

One of the horses caught his foot in a root and, stumbling, began to slide down a steep place. His rider was evidently thrown forward. There was a sound of struggling and more curses as the horse righted himself and the drunken rider remounted.

A consultation in low tones followed. Fraley could catch a word now and then. Pete was laughing that awful cackle of triumph, telling of Larcha’s attack and finish. She held her breath and clung to the tree with arms that were numb with tensity, expecting momentarily that the wicked little flashlight would play upon her face and reveal her to her enemies.

Then she heard Brand cry out: “Which way did the dog come? Up there? We’ll soon have her then. She can’t make time uphill. All set?”

The four horses wheeled and went up the mountain, directly away from where she clung in midair.

Larcha’s ruse had worked. He had not died in vain.

Chapter 3

Fraley’s head reeled as she clung to the tree and listened to the receding hoofbeats. She could feel the old tree sway under her; she had climbed so near to the top that her anchorage seemed very uncertain. She had a feeling that she was high above the world, held somehow in the hollow of God’s hand, and she laid her white face against the rough old trunk and closed her eyes. It seemed as if she scarcely dared to breathe yet, lest the men return, much less could she think of descending from her stronghold.

The searchers climbed higher and higher, until they were silhouetted for a moment against the distant bit of starry sky, and then disappeared down on the other side of the mountain. They had gone to search for her among their own kind, thinking she had taken refuge with someone. Their voices, which at first had been loud and clear, floating back in angry snatches, were suddenly shut off as they dropped from view. She drew a deep breath of relief.

But they would come back! When they failed to find her there, they would come this way again and search. It was not safe to go down now. There was no other spot for hiding that she knew of within miles, and she dared not venture into the unknown while they were yet hot on her trail. Besides, she knew that her progress would be slow indeed, for she must go cautiously. Well had she learned that there were many other men hiding within these strange mountain strongholds, who would be no safer companions than the ones from whom she would escape. Indeed, the way before her seemed as beset as the way behind.

How good it would have been if the shot that had stilled old Larcha’s barking had reached her own heart and sent her out of a world that was only full of sorrow and terror.

As the immediate fear of the men died away and strength began to return to the girl’s tired limbs and steadiness to her heart, she began to think about the dog. Had he died at once, or was he lying there in pain and wondering why she did not come to him? Her last defender, the only one in the world left who loved her, and he was stilled probably forever! There had not been a whimper from him since that shot and the dull thud that followed. And she had thought that he would go with her on her long, strange journey! Now she must go alone. It seemed hours that she clung there to her frail support high in the old pine. The night shut down more darkly. The stars flicked little pricks in the strip of the sky above the mountains more distinctly, and a thread of a moon came up and hung like a silver toy in the east, far off to the right. She shrank even from the bit of light it gave, lest her enemy might return. She dared not try to run away yet.

She tried to make a plan for her going, but somehow everything seemed all mixed up. She could not be sure which way the men would return. Also, there were cabins hidden deeply among the spurs of the foothills where dangerous characters lived. These she must avoid, although she had not even a very definite idea where they were located. There were paths that her mother had always warned her against in a general way, and yet they lay, some of them, between her and the great east that she must seek. Arriving each time from her round of problems, she would just close her eyes and pray,Oh God, You show me the way, please! You go with me!

It was hours later that she was startled into alertness again.

Voices had suddenly risen on the night air, detached, drunken voices, booming up along the horizon as if they had just emerged from another world.

She shifted her hands on the resinous tree and found them stiff and painful with their long clinging. She changed her position and shrank closer to the tree. The men were coming back!