0,49 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

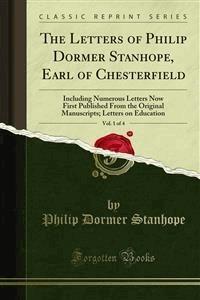

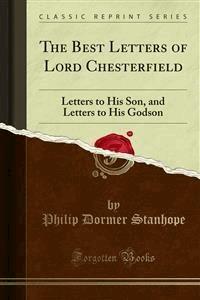

In "Letters to His Son, 1759-65," Philip Dormer Stanhope, the Earl of Chesterfield, composes a series of elegant and astute letters aimed at imparting wisdom to his illegitimate son. Through a blend of personal insight and social critique, Chesterfield articulates the principles of gentlemanly conduct, eloquence, and the importance of education in social and political spheres. The literary style draws from the epistolary tradition, showcasing not only a mastery of prose but also a keen psychological insight into human behavior and the complexities of societal interaction during the 18th century. The work serves as both a guide and a reflection of the Enlightenment's values, emphasizing reason, decorum, and the cultivation of one's social persona. Chesterfield, a prominent statesman and diplomat, was shaped by his own experiences in the courts of Europe and the intricacies of British society. His formidable education and upbringing, alongside his status as a member of the aristocracy, equipped him with a profound understanding of the social expectations placed on individuals. Chesterfield's paternal approach transcends mere advice; it becomes a legacy of social grooming that reflects the era's preoccupations with class, communication, and self-improvement. This book is an essential read for anyone interested in the art of letter-writing or the nuances of 18th-century etiquette. Chesterfield'Äôs epistles are rich in wisdom and wit, making them not only a historical artifact but also a timeless guide to personal and social development. Readers will find themselves enriched by his insights, which remain relevant in today's discourse on manners and personal philosophy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Letters to His Son, 1759-65

Table of Contents

LETTER CCXXXVII

LONDON, New-year's Day, 1759

MY DEAR FRIEND: 'Molti e felici', and I have done upon that subject, one truth being fair, upon the most lying day in the whole year.

I have now before me your last letter of the 21st December, which I am glad to find is a bill of health: but, however, do not presume too much upon it, but obey and honor your physician, "that thy days may be long in the land."

Since my last, I have heard nothing more concerning the ribband; but I take it for granted it will be disposed of soon. By the way, upon reflection, I am not sure that anybody but a knight can, according to form, be employed to make a knight. I remember that Sir Clement Cotterel was sent to Holland, to dub the late Prince of Orange, only because he was a knight himself; and I know that the proxies of knights, who cannot attend their own installations, must always be knights. This did not occur to me before, and perhaps will not to the person who was to recommend you: I am sure I will not stir it; and I only mention it now, that you may be in all events prepared for the disappointment, if it should happen.

G——-is exceedingly flattered with your account, that three thousand of his countrymen; all as little as himself, should be thought a sufficient guard upon three-and-twenty thousand of all the nations in Europe; not that he thinks himself, by any means, a little man, for when he would describe a tall handsome man, he raises himself up at least half an inch to represent him.

The private news from Hamburg is, that his Majesty's Resident there is woundily in love with Madame———-; if this be true, God send him, rather than her, a good DELIVERY! She must be 'etrennee' at this season, and therefore I think you should be so too: so draw upon me as soon as you please, for one hundred pounds.

Here is nothing new, except the unanimity with which the parliament gives away a dozen of millions sterling; and the unanimity of the public is as great in approving of it, which has stifled the usual political and polemical argumentations.

Cardinal Bernis's disgrace is as sudden, and hitherto as little understood, as his elevation was. I have seen his poems, printed at Paris, not by a friend, I dare say; and to judge by them, I humbly conceive his Eminency is a p——-y. I will say nothing of that excellent headpiece that made him and unmade him in the same month, except O KING, LIVE FOREVER.

Good-night to you, whoever you pass it with.

LETTER CCXXXVIII

LONDON, February 2, 1759

MY DEAR FRIEND: I am now (what I have very seldom been) two letters in your debt: the reason was, that my head, like many other heads, has frequently taken a wrong turn; in which case, writing is painful to me, and therefore cannot be very pleasant to my readers.

I wish you would (while you have so good an opportunity as you have at Hamburg) make yourself perfectly master of that dull but very useful knowledge, the course of exchange, and the causes of its almost perpetual variations; the value and relation of different coins, the specie, the banco, usances, agio, and a thousand other particulars. You may with ease learn, and you will be very glad when you have learned them; for, in your business, that sort of knowledge will often prove necessary.

I hear nothing more of Prince Ferdinand's garter: that he will have one is very certain; but when, I believe, is very uncertain; all the other postulants wanting to be dubbed at the same time, which cannot be, as there is not ribband enough for them.

If the Russians move in time, and in earnest, there will be an end of our hopes and of our armies in Germany: three such mill-stones as Russia, France, and Austria, must, sooner or later, in the course of the year, grind his Prussian Majesty down to a mere MARGRAVE of Brandenburg. But I have always some hopes of a change under a 'Gunarchy'—[Derived from the Greek word 'Iuvn' a woman, and means female government]—where whim and humor commonly prevail, reason very seldom, and then only by a lucky mistake.

I expect the incomparable fair one of Hamburg, that prodigy of beauty, and paragon of good sense, who has enslaved your mind, and inflamed your heart. If she is as well 'etrennee' as you say she shall, you will be soon out of her chains; for I have, by long experience, found women to be like Telephus's spear, if one end kills, the other cures.